Abstract

In this work we compare a novel model-based material decomposition (MBMD) approach against a standard approach in high-resolution spectral CT using multi-layer flat-panel detectors. Physical experiments were conducted using a prototype dual-layer detector and a custom high-resolution iodine-enhanced line-pair phantom. Reconstructions were performed using three methods: traditional filtered back-projection (FBP) followed by image-domain decomposition, idealized MBMD with no blur modeling (iMBMD), and MBMD with system blur modeling (bMBMD). We find that both MBMD methods yielded higher resolution decompositions with lower noise than the FBP method, and that bMBMD further improves spatial resolution over iMBMD due to the additional blur modeling. These results demonstrate the advantages of MBMD in resolution performance and noise control over traditional methods for spectral CT. Model-based material decomposition hence has great potential in high-resolution spectral CT applications.

Index Terms—: one-step reconstruction and decomposition, spectral CT, model-based iterative reconstruction, quantitative CT, deblurred CT, dual-layer FPD

I. INTRODUCTION

SPECTRAL CT has found increased application in diagnostic imaging with its ability to improve detection of contrast-enhanced lesions, provide virtual non-contrast images, estimate quantitative density measures of endogenous tissues and contrast agents, and reduce artifacts from beam hardening and metallic implants. Recent advances in flat-panel detector design which use multiple detection layers1 have the potential to extend these capabilities to cone-beam CT (CBCT) systems including dedicated (e.g., head and neck, extremities, dental, etc.) and interventional CBCT (e.g. mobile and fixed C-arms).

Multi-layer detectors offer many opportunities and challenges. Prototype flat-panel detectors with multiple layers enable energy discrimination in a similar packaging and format as traditional flat-panels by stacking two or more scintillator and semiconductor layers. Often additional filtration is put between the layers to change the x-ray spectrum arriving at the second (or deeper) layers. There are many trade-offs in the design of the scintillator thickness for each layer and the material and thickness of interstitial filters. For example, thicker filtration layers help to provide increased spectral separation between detection layers, which tends to improve material decomposition performance; however, thicker layers result in decreased detection efficiency and, thus, increased noise. Similarly, differences in scintillator thickness can also be used to customize spectral sensitivity; however, varied scintillator thickness can also lead to different spatial resolution in each spectral channel resulting in mismatches that can degrade quantification or lead to edge artifacts in material decomposition.

High spatial resolution is often one of the drivers for using flat-panel detectors. Scintillator thickness presents additional trade-offs for maintaining fine resolution capability with thicker scintillators generally yielding lower spatial resolution. Another potential resolution loss in multi-layer detectors arises from incomplete registration of the layers. That is, the pixel grids of the first and second layer are not perfectly aligned due to manufacturing constraint, or, more generally, are impossible to align exactly due to divergent beam effects. Traditional data processing that resamples data onto a common grid involves interpolation and consequent resolution degradation.

Model-based reconstruction and decomposition offers potential solutions to the challenges of multi-layer flat-panel CBCT. In particular, in contrast to projection-domain2 and image-domain decomposition3 in which material density estimates are computed in a staged decompose-then-reconstruct or reconstruct-then-decompose process, there are a growing number of so-called one-step approaches4;5;6, wherein material density estimates are computed directly from projection data. Not only can these approaches explicitly model the differences in sampling and geometry of the detection layers without the need for data interpolation; these approaches can be modified (as in Wang et al.7) to model detector blur effects.

In this work, we adapt model-based material decomposition approaches to a prototype dual-layer flat-panel CBCT system. Both model-based approaches with and without blur modeling are applied and the high-resolution capability of the approaches is investigated and compared to traditional image-domain data processing.

II. METHOD

A. Model-based Material Decomposition (MBMD)

The following is a brief overview of our implementation of MBMD. We begin with the following forward model:

| (1) |

where the mean measurements, , are indexed by n (over both detector pixels and rotation angles), and are related to the material density parameters, ρjk, which are indexed over voxel j and material k. This relationship takes into account the energy-dependent mass attenuation coefficients qmk where m is the energy index; and the coefficients, sim, which model all the elements contributing to spectral sensitivity including incident beam spectrum, scintillator type and thickness, energy weighting, etc. Note that we differentiate between pre-detector blur indices, i, and post-blur indices, n; where the blur kernel is given by bin. This blur model is general; however, we will focus on independent shift-invariant blur for each detection layer. Also, note that the projection operation, specified by aij permits arbitrary system geometries including different geometries for each detection layer. Lastly, we permit modeling of additional gain effects (e.g. automatic exposure control) through gi. This forward model may be written compactly using matrix-vector form as

| (2) |

We choose to estimate ρ from the measurements y using the following regularized objective function:

| (3) |

This objective was previously reported in Wang et al.7 and allows for specification of the inverse of the data covariance and an arbitrary regularizer R(ρ). In this work, we restrict ourselves to weighting by the inverse of the variance of the data and a quadratic regularizer. The objective function was solved using a preconditioned method described in Tivnan et al.8.

Note that this system model is general and permits the investigation of both algorithms with and without blur modeling. In the case of no blur modeling, the operator B becomes the identity matrix. In this work, we compared three material decomposition methods: filtered-backprojection followed by image-domain decomposition, idealized MBMD with no detector blur modeling (iMBMD), and model-based material decomposition with system blur model (bMBMD).

B. High-Resolution Material Decomposition Experiments

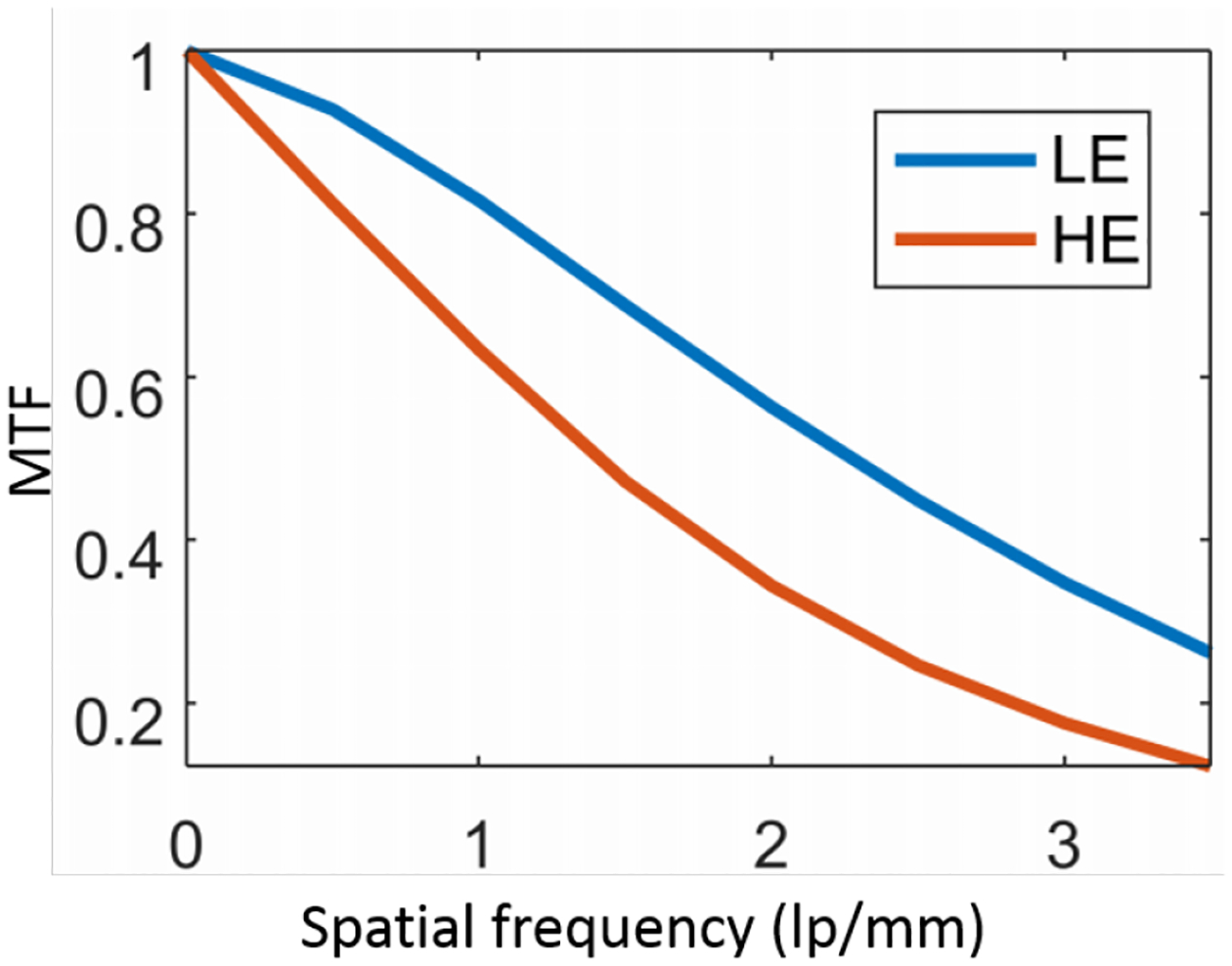

Physical investigations were conducted on a prototype spectral CBCT test-bench (Figure. 2). The system consists of a rad/fluoro X-ray source (Rad-94, Varex Imaging, San Jose, CA), a rotary stage (Alio Industries, Arvada, CO), and a prototype dual-layer a-Si detector provided by Varex Imaging. Both the “low-energy” flat panel (top layer) and the “high-energy” panel (bottom layer) have 2880 × 2880, 150 μm pixels. The low-energy layer has a 200 μm CsI scintillator, and the high-energy layer has a 550 μm CsI scintillator. Between the two layers exists a 1 mm interstitial copper filter. The detector Modulation Transfer Functions (MTFs) of each layer have been measured in previous work1 and are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 2:

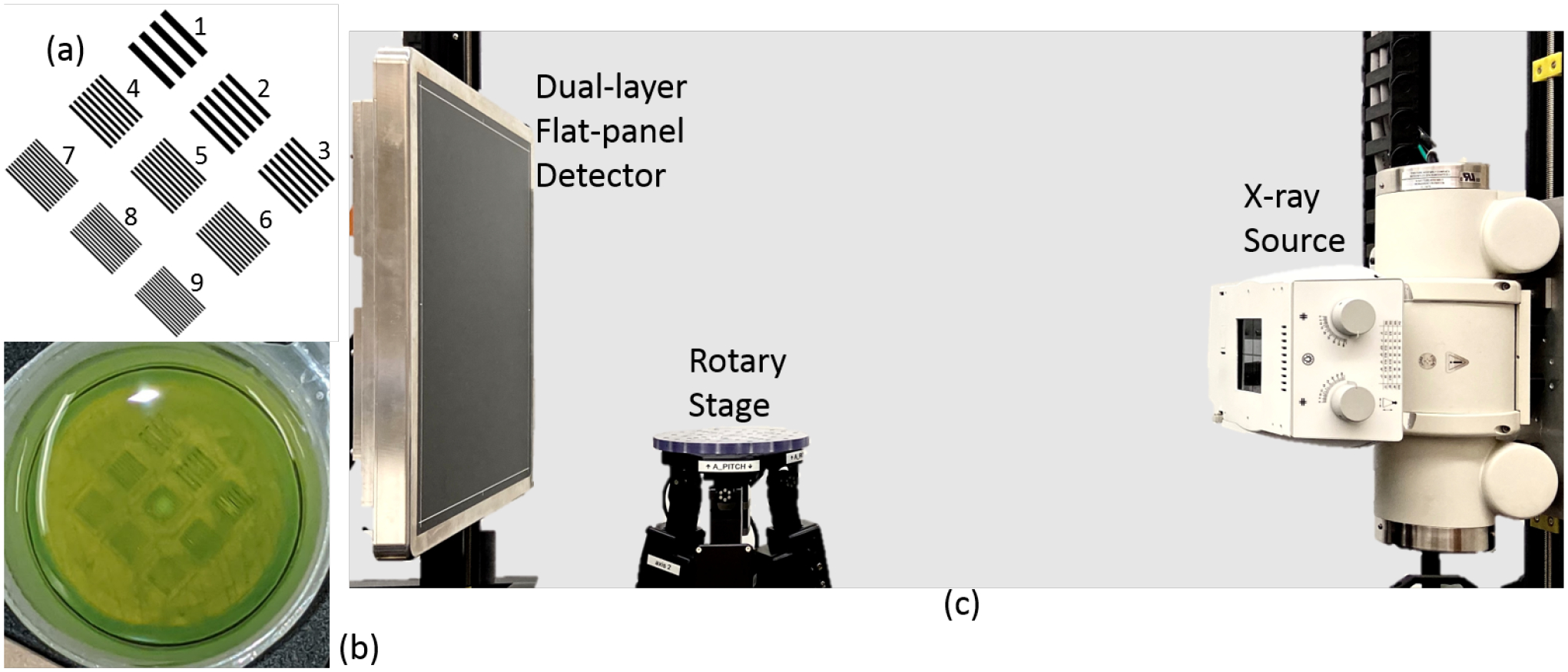

(a) A high-resolution phantom design and 3D-printed line-pair phantom. Line pair densities of groups 1 – 9 range from 1 lp/mm to 5 lp/mm in 0.5 lp/mm increments (however, not all line pairs appear due to finite spatial resolution of the printer). (b) Photo of the 3D printed phantom immersed in 50 mg/mL iodine solution. (c) Illustration of the experimental dual-layer detector spectral CT test-bench used in physical experiments.

Fig. 1:

MTFs of the low energy (LE) and high energy (HE) channels of the detector

To investigate the high-resolution capabilities of the prototype system and the effect of different data processing schemes, a custom iodine-enhanced phantom was constructed. The phantom consists of nine groups of 3D-printed line pairs immersed in 50 mg/mL iodine solution (Figure. 2). The phantom is designed with variably sized line pairs from 1–5 lp/mm in 0.5 lp/mm increments. Due to resolution limits of the 3D printer used in this work, the Peopoly Moai SLA printer, not all line pairs are accurate representations of the original design. In particular, finer line pairs are printed somewhat thinner and the smallest line pairs are completely fused together. Thus, while this phantom exhibits high-resolution features that help probe the resolution limits of the system, the line pair frequencies themselves are not quantitative.

Projection data were acquired using an X-ray technique of 90 kVp and 1 mAs per frame. The phantom was rotated 360° and 360 projections were acquired with uniform angular sampling. Native 150 μm pixels were used without binning. The source-to-axis distance (SAD) was 828.9 mm, and the average source-to-detector distance (SDD) for the two layers was 1129.2 mm. Each detector layer was calibrated individually using the geometric calibration method described in Cho et al.9.

As discussed above, three separate reconstructions/material decompositions were performed: FBP and image-domain decomposition, iMBMD, and bMBMD. The blur operator B in the bMBMD forward model accounts for the source and detector blur in each of the two spectral channels. The reconstructed volumes used 400 × 400 × 3, 0.11 mm cubic voxels. For the two MBMD approaches, the iterative algorithm in Tivnan et al.8 was used with 60 main iterations, each with 5 subiterations for inverse Hessian application. Quadratic regularization strength was chosen to be in a regime where iMBMD resolution was limited by system blur (e.g. smaller regularization values did not improve spatial resolution) and bMBMD regularization strength was chosen to illustrate improved resolution while limiting overall noise. The FBP reconstruction consisted of separate reconstructions of the high- and low-energy channels into volumes with a common coordinate system. Image domain material decomposition was performed using an empirically selected linear combination of the high- and low-energy reconstructions with a normalization to approximate proper concentrations.

III. RESULTS

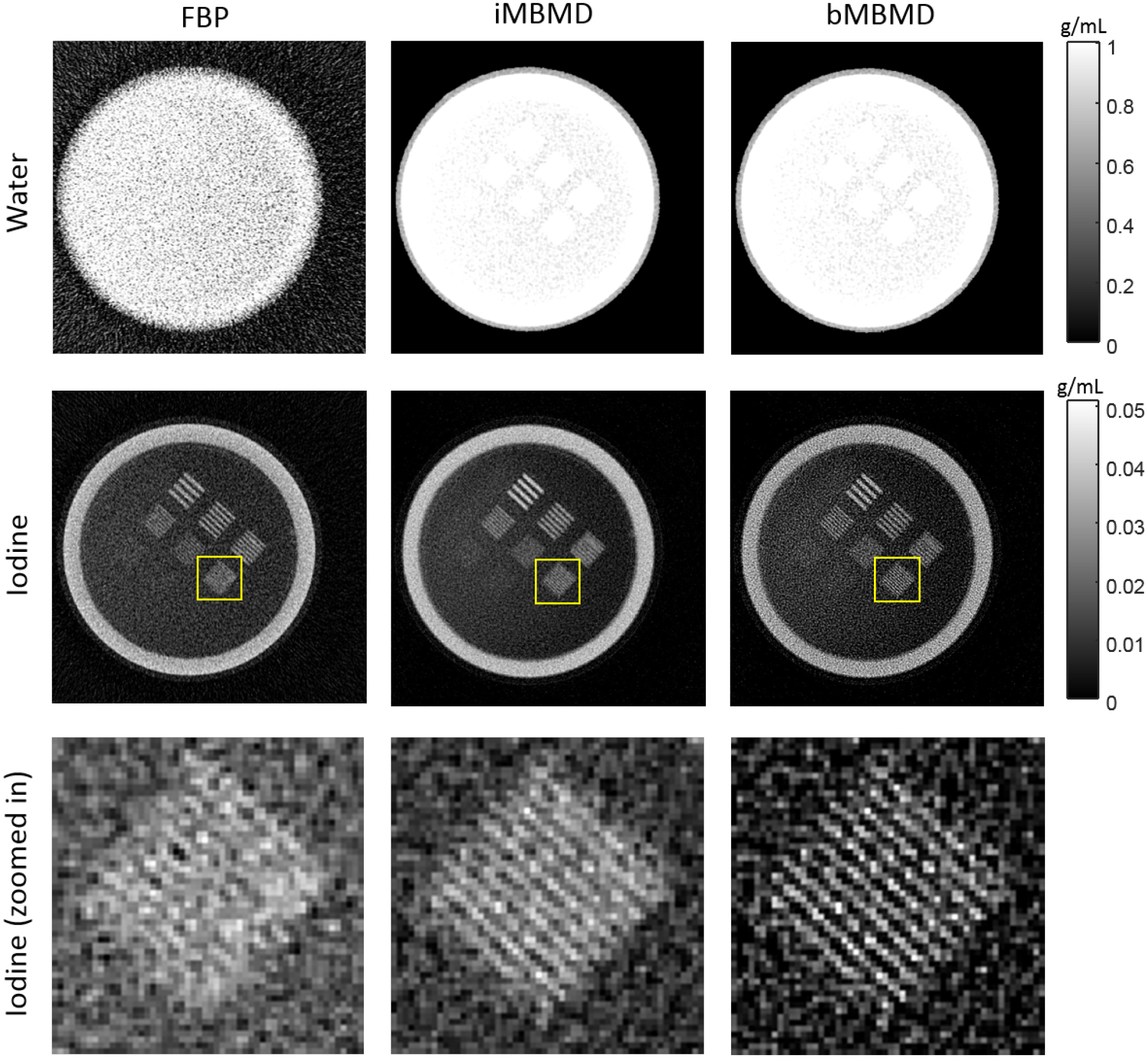

Reconstructions are shown in Figure 3. The FBP result suffers from visibly higher noise than the other two methods. This noise was dominated by higher noise in the high-energy channel that propagated through to the decomposition via the linear combination of channels. The iMBMD approaches exhibits less noise in the reconstruction - likely to the improved system model and statistical modeling of noise. Advantages are most prominent in the zoomed images of the iodine basis material. (Note that line pair groups 7 – 9 do not appear in the reconstructions due to 3D-printing restrictions not data processing constraints.) It appears there is also a subtle improvement in spatial resolution in iMBMD over FBP. In the bMBMD images, we see further improved spatial resolution (due to the blur modeling); however, there does appear to be somewhat increased noise. These results are consistent with prior work10 in model-based iterative reconstruction where blur modeling methods outperform methods without blur modeling in that they extend the feasible range of noise-resolution tradeoffs. That is, where the iMBMD method is limited by the unmodeled system blur, the bMBMD method can achieve higher resolution albeit at increased noise.

Fig. 3:

Reconstruction and material decomposition of the iodinated line-pair phantom using FBP, iMBMD, and bMBMD.

IV. DISCUSSION

In this work we have explored the use of one-step model-based material decomposition methods for a dual-layer flat panel prototype system. We have applied standard data processing techniques as well as model-based iterative methods with and without blur modeling. These initial studies suggest that the model-based approaches have the ability to provide increased imaging performance - e.g. decreased noise at similar resolution and/or higher spatial resolution through detailed modeling of the measurement noise, sampling, and system blurs. This work illustrates that model-based processing has the potential to recover imaging performance and help balance the inherent trade-offs present with the design of multi-layer detectors.

In ongoing work, we are refining the imaging targets used for these kinds of high-resolution studies including the use of alternate phantom construction methods and the use of micro-CT to obtain high-resolution ground truth for comparison. Similarly, quantitative analysis of these approaches over a range of regularization strength is underway to illustrate the limiting performance of iMBMD as compared with bMBMD. Moreover, we are exploring alternate regularization schemes to provide increased advantages in the trade-off between noise and resolution.

Acknowledgments

This work supported in part by NIH grant R21EB026849 and R01EB025470, and an academic-industry partnership between Johns Hopkins University and Varex Imaging Corporation.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lu M, Wang A, Shapiro E, Shiroma A, Zhang J, Steiger J, and Star-Lack J, “Dual energy imaging with a dual-layer flat panel detector,” vol. 1094815, no. March, p. 40, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Alvarez RE and Macovski A, “Energy-selective reconstructions in x-ray computerised tomography,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 21, no. 5, p. 733, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Liu X, Yu L, Primak AN, and McCollough CH, “Quantitative imaging of element composition and mass fraction using dual-energy ct: Three-material decomposition,” Medical physics, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 1602–1609, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schmidt TG, Barber RF, and Sidky EY, “A spectral ct method to directly estimate basis material maps from experimental photon-counting data,” IEEE transactions on medical imaging, vol. 36, no. 9, pp. 1808–1819, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mechlem K, Ehn S, Sellerer T, Braig E, Munzel D, Pfeiffer F, and Noël PB, “Joint statistical iterative material image reconstruction for spectral computed tomography using a semi-empirical forward model,” IEEE transactions on medical imaging, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 68–80, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tilley II S, Zbijewski W, and Stayman JW, “Model-based material decomposition with a penalized nonlinear least- squares CT reconstruction algorithm,” Phys Med Biol, vol. 64, no. 3, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang W, Tivnan M, Gang GJ, Ma Y, Cao Q, Lu M, Star-Lack J, Colbeth RE, Zbijewsku W, and Stayman JW, “Model-based material decomposition with system blur modeling,” in Medical Imaging 2020: Physics of Medical Imaging. SPIE, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tivnan M, Wang W, and Stayman JW, “Preconditioned algorithms for model-based iterative reconstruc tion and material decomposition from spectral ct data,” arXiv:3010843, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cho Y, Moseley DJ, Siewerdsen JH, and Jaffray DA, “Accurate technique for complete geometric calibration of cone-beam computed tomography systems,” American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM), Mar 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tilley S, Jacobson MW, Cao Q, Brehler M, Sisniega A, Zbijewski W, and Stayman JW, “Penalized-likelihood reconstruction with high-fidelity measurement models for high-resolution cone-beam ct imaging,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 988–999, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29621002https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8125700/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]