Abstract

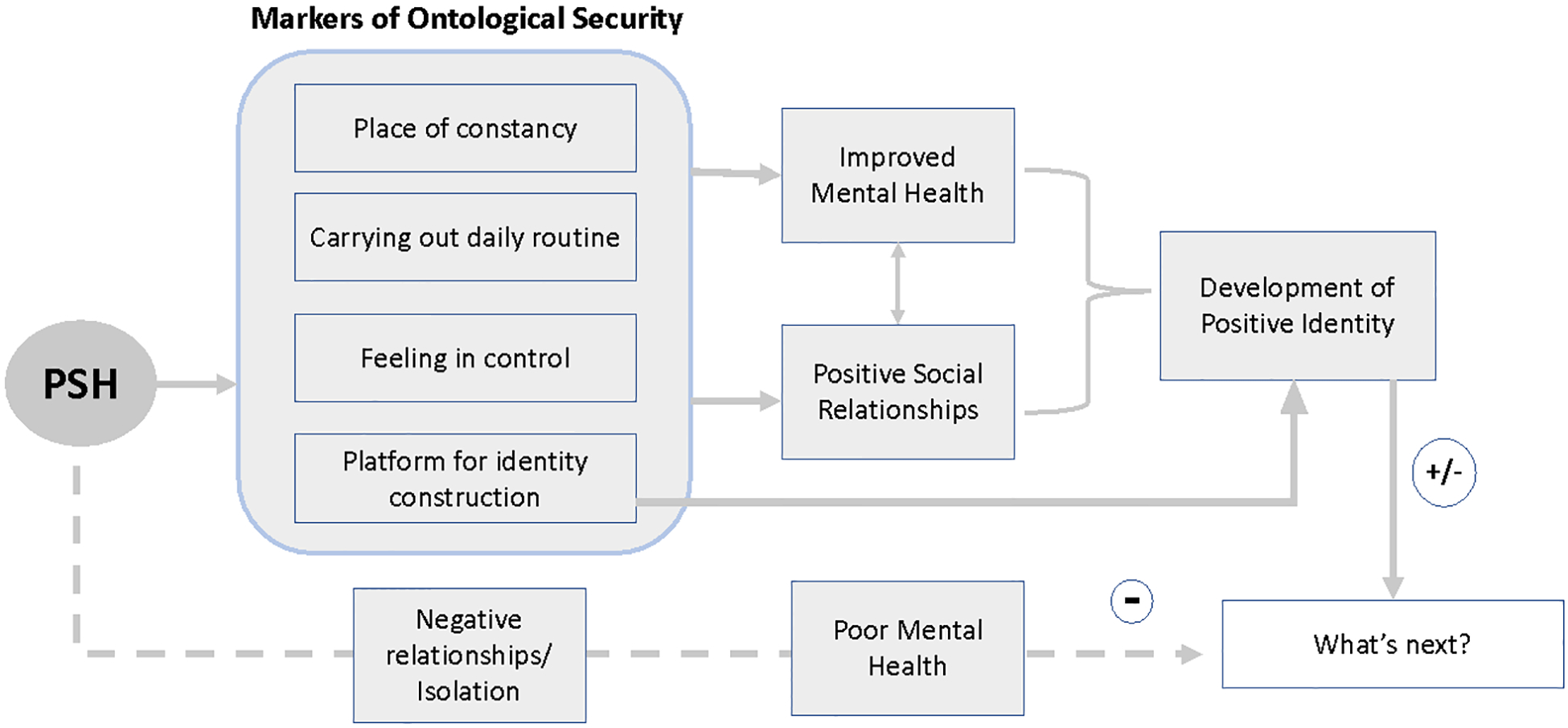

This qualitative study of 29 young adults (aged 18–25) living in permanent supportive housing (PSH) resulted in a grounded theory that shows how PSH generally provides a sense of ontological security for young adults—much like for older adults—who are also experiencing significant developmental change processes. Simply stated, ontological security refers to a concept of well-being in the world that is rooted in a sense of order in one’s social and material environment. Thematic analyses indicated that the presence of markers of ontological security (for example, constancy, routine, control) positively affected participants’ mental health and well-being, which helped with positive identity construction. An increase in ontological security also related to residents’ social environment and participants’ ability to improve on social relationships, which supported improved mental health and sense of self. Most young adults in this study regarded living in PSH as “a chance to start my life” and considered the question of “What’s next?” within a normative developmental trajectory. Counterexamples that demarcate the limits of these thematic findings are included in the grounded theory model, including some experiences of social isolation and struggles with mental health associated with less positive orientations toward “what’s next.”

Introduction

For adults who have experienced long-term homelessness, PSH using a housing first approach—or the provision of immediate access to low-barrier, affordable housing along with wrap-around services—has been effective at ending homeless (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, 2010) and providing a secure base for identity construction (Padgett, 2007). PSH has also been advanced as a solution to youth homelessness (Dworsky et al., 2012; Gaetz, 2014), yet there has been relatively limited research on whether such programs promote healthy development, including identity construction (Henwood, Redline, and Rice, 2018; Kozloff et al., 2016a, 2016b; Munson et al., 2017). The transition from youth to young adulthood is an important period for healthy biopsychosocial development, which is disrupted by experiences of homelessness and related adverse childhood experiences (Catalano et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2018) and can have adverse health consequences throughout life (Felitti et al., 1998; Mackelprang et al., 2014).

In a 12-month prevalence study using a nationally representative sample, Morton et al., (2018) estimated that 3.48 million young adults aged 18–25 experience homelessness in the United States. Higher homelessness rates occur among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young adults; underserved racial and ethnic minority young adults; and young adults with limited education and/or who are parenting. Given the heterogeneity within this population, a one-size-fits-all housing model for young adults is unlikely, whereas helping young people successfully transition out of homelessness will likely require an array of support services and housing options. Although PSH is considered the clear solution for chronically homeless adults (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, 2010), it is just one of several housing models—including transitional housing, rapid rehousing, and host homes—being advanced for young adults experiencing homelessness (Curry and Abrams, 2015; Curry and Petering, 2017; Maccio and Ferguson, 2016).

Although few studies have examined the implementation of PSH specifically for youth, initial research suggests that while it effectively ends homelessness (Kozloff et al., 2016a), PSH programs may not meet the needs of transition-age youth due to design or implementation flaws (Gilmer 2016). Research also suggests implementation of PSH for youth may differ from PSH for adults because more youth self-refer. Housing for youth is often transitional and involves roommates; services likely focus on education and gaining meaningful employment than on health services (Gilmer et al., 2013). In one of the few studies focused on the experiences of youth or young adults living in PSH, Munson et al., (2017) found that residents received mixed messages about the need to become independent while following restrictive program rules—a consistent theme in other research on transitional housing programs for youth (Curry and Abrams, 2015). How do housing models for youth (such as PSH and transitional housing) differ, and how do those differences affect youth development?

In this qualitative and descriptive study, we expand on youth experiences in housing programs by using ontological security—or well-being in the world that is rooted in a sense of constancy in one’s social and material environment (Giddens, 1990; Laing, 1965)—as a sensitizing framework to examine the perspectives of formerly homeless young adults who are living in PSH. Padgett (2007), who found that adults living in apartments of their own experienced conditions conducive to the development of ontological security, was the first to apply the concept to the field of homelessness. As outlined by Dupuis and Thorns (1998), these conditions include experiencing housing as (1) a place of constancy, (2) where daily routines can be enacted/carried out, (3) where people feel “most in control in their lives,” and (4) as a place “around which identities are constructed.” Padgett (2007) also found that the presence of ontological security prompted important questions about “what’s next?” for adults whose lives and personal goals had long been disrupted by homelessness. Prior to its application to homeless services, the majority of studies of ontological security focused on the concept’s utility in exploring how aspects of the housing or residential environment—particularly home ownership—can foster ontological security (Cairney and Boyle, 2004; Kearns et al., 2000; Vigilant, 2005). In this study, we seek to understand whether PSH provides ontological security for young adults undergoing significant developmental change processes and how young adults view the presence or absence of ontological security as affecting their development.

Methods

In the following section, we describe recruitment and data collection efforts along with a description of the data analytic approach. We note that the authors’ institutional review board approved all study procedures.

Participants and data collection

During June 2014, 29 young adults (18–25 years old) living in four PSH buildings in the Los Angeles area were recruited using convenience sampling methods (fliers posted at housing sites and word-of-mouth recruitment from onsite agency staff). All participants provided verbal informed consent and completed the study in English; no participant names were collected. Participants completed an interviewer-administered survey and semi-structured qualitative interview that lasted approximately 1.5 hours. Youth received $25 for participation. Interviewer-administered survey items asked about demographics, housing characteristics, and mental health. Qualitative interviews focused on participants’ experiences in PSH, including discussion of their housing program, unit, and neighborhood. Qualitative interviews also focus on how relationships with family, friends, or providers may have been impacted by moving into PSH; improvements or challenges experienced since being housed; and how PSH has affected their lives. Interviewers had previous experience working on a federally funded study of homeless youth and had training on the importance of establishing trust and building rapport. Qualitative interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and entered into ATLAS.ti software for data management and analysis.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed using a grounded theory approach that uses constant comparative analysis and outlines procedures for coding qualitative data (Charmaz, 2006; Strauss and Corbin, 1990). This involved reading and re-reading all transcripts and then having investigators independently code and then co-code transcripts. For this study, two authors co-coded all transcripts. Sensitizing concepts representing domains of ontological security (for example, privacy and daily routines) were included as part of the initial codebook, along with codes representing the overall domains included in the interview guide (for example, current living situation, housing challenges, typical day). Open coding of transcripts generated additional codes (such as goals, life skills, and outlook on life) that were applied to all transcripts. During the coding process, discrepancies resolved through consensus to develop an initial set of themes. Negative case analysis, in which transcripts were reviewed specifically to find counterexamples to our generalized themes, was also conducted. A final analysis phase determined the relationship between themes, which resulted in a grounded theory. The first three authors discussed and finalized individual themes, negative case examples, and the final grounded theory, which the entire team reviewed and approved.

Results

In the following, we present the demographic characteristics and self-reported service utilization of the sample followed by an emergent grounded theory model. Themes that explain the model are also described.

Sample characteristics

As shown in Table 1, youth in this study were in PSH for an average of nearly 18 months, were 23 years-old on average, and were mostly male (62 percent). Slightly more than 41 percent were African-American, followed by Latinx (24 percent), mixed or other race (21 percent), and White (14 percent). Nearly 68 percent identified as heterosexual, followed by 21 percent gay or lesbian and 7 percent bisexual. Most youth reported a high school (62 percent) or more than high school education (17 percent); 28 percent were currently in school (50 percent of those were taking college courses), and 45 percent reported that they had continued their education since they had been in housing. Most youth reported they were currently working full or part-time (41 percent) or looking for work (45 percent; employment categories are not mutually exclusive). About 45 percent of respondents reported that they had a history of foster care involvement. More than half (55 percent) had been arrested previously, 48 percent had been incarcerated previously, and 21 percent reported an incarceration experience prior to their 18th birthday. Seventeen percent of respondents reported that they had at least one biological child.

Table 1:

Demographic Characteristics and Service Utilization (n=29)

| N (%) / mean (Standard Deviation) | |

|---|---|

| Months in housing | 17.84 (11.08) |

| Age | 23.28 (1.83) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 18 (62.07) |

| Female | 11 (37.93) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| African-American | 12 (41.38) |

| Latinx | 7 (24.14) |

| White | 4 (13.79) |

| Mixed or other race | 6 (20.69) |

| Sexual orientation identity | |

| Gay/lesbian | 6 (21.43) |

| Bisexual | 2 (7.14) |

| Heterosexual | 19 (67.86) |

| No preference | 1 (3.57) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 6 (20.69) |

| High school | 18 (62.07) |

| >High school | 5 (17.24) |

| School since housed* | 13 (44.83) |

| Currently in school | 8 (27.59) |

| Current school level (of those in school) | |

| High school/GED1 | 1 (12.50) |

| College | 4 (50.00) |

| Trade/technical school | 3 (37.50) |

| Have any biological children | 5 (17.24) |

| Employment (not mutually exclusive) | |

| Working full or part-time | 12 (41.38) |

| Unemployed, not looking for work | 6 (20.69) |

| Un/under-employed and looking for work | 13 (44.83) |

| Student | 9 (31.03) |

| Odd jobs | 1 (3.45) |

| History of foster care | 13 (44.83) |

| Ever arrested | 16 (55.17) |

| Ever incarcerated | 14 (48.28) |

| Incarcerated <18 years old | 6 (20.69) |

| Incarcerated >18+ years old | 11 (37.93) |

| Benefits | |

| Supplemental Security Income | 5 (17.24) |

| General Relief | 15 (51.72) |

| Unemployment | 1 (3.45) |

| Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program | 20 (68.97) |

| HUD/Section 8 | 8 (27.59) |

| Temporary Assistance for Needy Families | 1 (3.45) |

| None | 3 (10.34) |

| Services | |

| Therapy or counseling | 19 (65.51) |

| Food assistance | 15 (51.72) |

| Job help | 15 (51.72) |

| Medical | 13 (44.83) |

| Condoms/birth control | 11 (37.93) |

| Housing Arrangement | |

| Living alone | 12 (41.38) |

| Living with roommate(s) | 15 (51.72) |

| Living with child(ren) | 2 (6.90) |

The most common financial benefit that youth reported receiving was the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (69 percent), followed by General Relief (52 percent). Since moving into housing, 66 percent of youth reported receiving counseling or therapy, 52 percent assistance with free food or meals, 52 percent job services, 45 percent help with medical/health care, and 38 percent access to condoms or birth control. A little more than half of respondents reported that they lived in a housing unit with a roommate (52 percent), while 41 percent reported living alone, and 7 percent were living with their child(ren).

Grounded theory

Figure 1 displays a grounded theory model of the relationship between ontological security, mental health, social relationships, and identity formation based on the experiences of young adults living in PSH. As shown, moving into PSH generally brought with it Dupuis and Thorns’ four traditional markers of ontological security. Those markers are to have a place: (1) of social and material constancy; (2) where daily routines can be enacted and carried out; (3) “where people feel most in control in their lives because they are free from surveillance;” and (4) “around which identities are constructed” (Dupuis and Thorns, 1998: 29). As described in theme 1, the presence of these markers of ontological security generally had positive impact on participants’ mental health and well-being, which helped with positive identity construction. In theme 2, we note how increased ontological security also relates to residents’ social environment and participants’ ability to improve upon different types of social relationships (familial, social, romantic, and with service providers), which supported improved mental health and sense of self. In the third theme, we discuss how most young adult PSH residents also took up Padgett’s (2007) emergent theme of “what’s next?” Importantly, however, young adults often saw it as, “a chance to start my life” (SP022), leaving their past behind and moving to the next stage of life given an improved sense of self-identity. This report describes each theme with elucidating and supporting quotes. Figure 1 includes counterexamples that demarcate the limits of each generalized theme by the possible experience of young adults being more socially isolated and continuing to struggle with mental health in PSH, resulting in a less positive outlook in terms of “what’s next.”

Figure 1.

Grounded theory model of the relationship between ontological security, mental health, social relationships, and identity formation based on the experiences of young adults living in PSH.

Theme 1: Improved mental health and positive identity through increased ontological security.

Participants’ descriptions of their experiences since moving into PSH were replete with markers of ontological security. When asked how life has changed, SP07 responded in a way that makes clear how PSH enables him to carry out daily routines and have a safe space that he controls. He said, “Well, first of all I have a roof over my head and shower so that makes me happy. Being able to cook is another thing because I love to cook and bake. So being able to have my own food and stuff like that, I love that…But I think the most valuable thing that I love about having my apartment is that I have my own personal space where I can just shut the door and have everybody outside the world leave me the hell alone. I think that’s the most valuable thing to me.”

Some participants were explicit about the positive impact PSH has had on mental health. SP16 said, “My mental health has changed a lot. I’ve been a lot healthier and more stable. My happiness has changed a lot. And it has to do with my mental health.”

Others described the specific effects of PSH on their well-being. SP23 explained, “I’ve noticed just brain chemistry, like my mind works better. I’m able to think more clearly. I don’t have as many paranoid thoughts as I used to. I still have sleeping issues, but I’m able to sleep better; it’s more consistent. I worry a lot less.”

The consistency in environment and ability to carry out daily routines was important. SP03 explained, “I have to keep organized and I think this apartment helps me keep organized because a lot of times my memory comes and goes and I’ve actually been able to kind of like better that since I’ve been here because now I have a calendar everywhere and I can put everything everywhere to where every room I go to I can always know what did I need to do, what did I forget. I can make lists. I can listen to music. There’s no one else I’m disturbing and I can just be free.”

SP09 reflected on life before and after accessing PSH, saying, “You no longer bounce around shelter to shelter, you’re no longer having curfews like you’re in prison and having chores, like in a halfway house, and having to answer to people, and be treated like you’re some criminal because you don’t have any support and you’re homeless. They treat all homeless people the same, like you’re all crazy, like you’re all on drugs, or alcoholics, or can’t handle money, or don’t want to get a job, or ignorant, or stupid, or lazy, all those stereotypes. So you don’t have to deal with that anymore.”

For some, having a place of their own was novel. As SP15 explained, “It’s just from being the streets, like, just like straight like, even though I knew what I was going to get into with my other roommates, it was just joyfulness, like knowing that you have somewhere, you have your like all your own keys and you can go in your own room when you never had that all your life. So it’s like awesome, like you know? It’s one of my first summers in all my life that I’ve had my own room, you know?”

Participants generally agreed that having an apartment instilled a sense of ontological security that ultimately helped with identity construction and their ability to express their personality. As SP03 expressed, “I like the fact because you get to see your house build. You get to see your house growing. And especially when it comes to being just human, you get to see your personality spread throughout the room.”

Theme 2: Social dimensions of ontological security.

Markers of ontological security brought about by the physical home environment that PSH provides can also influence the social environment and residents’ capacity for relational growth. In fact, most participants discussed how having an apartment influenced their relationships. For example, SP01 said, “Now I have a place that I can call my own. And I can tell my friends or girlfriend or family members to come over and spend time with me. So it’s definitely good to have a place that people can come over and spend time with me and stuff like that, instead of having to meet up somewhere public or whatever the situation is.”

SP06 said, “I’m more willing to have friends due to the fact now I know like okay they have a place to come over. They don’t have to kick it with me in my car or at the shelter. Because you kind of feel like that you won’t be respected as much because of your living situation so yeah I made more friends.”

Some participants discussed getting rid of bad influences or old friends for new and better influences. As SP16 described, “I got better friends now. And mostly, I see [provider name], my caseworker, I see him as a friend. My roommate, he’s one of my closest friends. And just some neighbors, they’re friends of mine, I dropped a lot of friends I was with because I wasn’t doing good with them. And that’s when I saw I was in a better position, so like I wasn’t, as much as I, and I tried, as much as I wanted to help, I knew I really couldn’t. So I just had to, you know, tell them, ‘hey, you can’t come back’ and so I just kind of changed my friends completely.”

SP14 explained it differently by saying, “I said I was making a lot of bad friends, but you know, they weren’t really friends, it was just they were using me because I would share my money and my things.”

Some participants, however, did not feel like having an apartment necessarily improved their social relationships. SP17 said, “I’m not going to lie, it feels good and happy to have your own spot, but all that I got from when I was homeless and in a shelter, now that I have my own place, technically, I’m still alone. Even though I have a roommate and stuff and I have [the housing program], it’s like you feel alone because you don’t have your family or stuff like that.”

The people who felt isolation even after moving into an apartment also often talked about struggling with their mental health. SP17, for example, went on to say, “So depression, insomnia, sometimes not being able to sleep, has stayed the same for me. And then the mentality of being homeless again is hard to really get rid of.”

Some participants also expressed concern about the social environment they experienced within the PSH program. As SP07 recounted, “I get harassed here by some residents. Some of the residents that were causing the issues have left. They got evicted or they moved away or whatever. And so that was better, starting to get better, but there are still a couple residents here who are very disruptive and they harass multiple residents for no reason.”

While ongoing struggles with mental illness and/or newfound acquaintances were important counterexamples, most PSH residents identified how improved social relationships improved their mental health and well-being and their sense of self. SP015 explained how housing has improved his relationships, self-confidence, and ability to stay out of jail, saying, “It’s not losing touch, it’s losing negative touch…Because if you’re already negative, and you surround yourself with negative people it’s going to be a negative outlook. But if you’re negative and you surround yourself with positive maybe you can be more positive to yourself…My life improved a lot in the positive way whereas that before when I was in the homeless shelter, straight up…I just had no self-confidence. I was like, you know, I’m broke, I ain’t got nothing, so I’m going to do criminal stuff. So that was the stuff I knew what to do at that point. So when I finally got my housing I realized that I have housing now so I don’t have to do that no more. So I have to better keep my housing and better myself. So as far getting my housing it just stopped me from going back to jail. And that’s been like my whole life, I always went to jail because I didn’t have no house, so I always had to steal food. I’d steal something to give to someone so I could stay at their house for a night, like you know what I mean?”

Theme 3: “What’s next” developmentally?

Padgett’s (2007) finding that older adults brought up “what’s next?” questions after finally getting into one’s own apartment was also applicable to our younger adult sample. Participants described a feeling that with an apartment, “It felt like…this is the chance for me to start my life” (SP02). For many, questions about the future were framed as part of a specific developmental stage. SP14 said, “When I was homeless I felt the future seemed bleak, I didn’t know what was going to happen to me…finally it’s just I got somewhere to stay, so now I feel like it’s possible, soon I’ll be driving my own car, I’ll be saving up for my own house, and I’ll find somebody and settle down, it just seems positive.”

Similarly, SP01 explained, “So this is just that next level. Just like getting a car. It’s that next level in life. You’re thinking differently. You have more time to do things because you can get places quicker. It just puts you in a different mindset. A more responsible mindset and a more mature mindset. Just having all these responsibilities. Having to take care of it in order to keep it. So definitely put me in a different mindset.”

When asked about his thoughts on moving forward, SP16 said, “I see myself as being a great dad. I see myself as, I don’t know, just, I want to be a dad, you know? And I know I can do it now. I just need to get a couple more things. It’s really just getting more work. And just raising my son. But I don’t plan on getting into trouble. I’m just planning down the road, you know, playing with grandkids. And, you know, this [PSH agency] is a place that helped.”

Despite programs referring to their service model as “permanent” supportive housing, a few participants aged 24–25 noted they were concerned for their future. SP07 explained, “I’m 25 now so I only have one more year before I don’t know what the hell’s going to happen. You know, I only have one more year before they decide, oh well you know what? She’s 26 and this is for Section 8. So Section 8 can just suddenly decide not to pay for me to stay here any longer. And then I wouldn’t have a place to stay and I’d be homeless again. So and there’s no services for them to help you find another place to live or get on other housing lists or whatever because then there’s those waiting lists. And then on top of that now since I’ve past the 24 mark, they don’t consider me TAY [transition age youth] anymore so I’ve gotta find adult housing and that’s even harder than youth housing and so there’s a whole bunch of other issues. So it’s kind of frustrating and stressful for me because I don’t know 100 percent what my next year is going to be like.”

Discussion

The concept of ontological security, which was useful in capturing the experience of older adults living in PSH who had experienced a lifetime of trauma (Padgett, 2007; Padgett et al., 2012), also proved useful in organizing the experience of younger adults living in PSH. In this study, the relationship between markers of ontological security, mental health, and social relationships suggest that PSH has the potential to help young adults develop a more positive identity from which to consider their future. In fact, the “what’s next?” question was closely tied to participants’ sense of moving to the next developmental life stage such as going to school, getting a car, or buying a house. In general, “emerging adulthood” is also marked by a move away from a family of origin, away from adolescent peer groups, and toward more stable young adult relationships, including strong romantic attachments that can lead to marriage or long-term partnerships (Arnett 2000; Arnett 2001). Findings from this study suggest PSH can help young adults’ thinking return to a more “normative” young adult developmental process, resulting in network shifts and a focus on future stability and relationships. This shift in thinking could replace what researchers of homeless youth development often say, which is that homelessness derails youth from “normal” developmental trajectories, exacerbating the social distance from parents and family, and increasing the engagement in deviant peer networks (Milburn et al., 2009).

Our study findings indicate the benefits of having a home may include improved mental health and social relationships for young adults and may have implications for the timing of screening and brief mental health interventions for homeless youth transitioning into housing programs (Harpin et al., 2016). Improved social relationships found in young adults in PSH underscore the impact of the built environment on social relationships and suggest that both the physical and social environment may relate closely to the concept of ontological security (Giddens, 1990; Laing, 1965). It is difficult to determine the extent to which young adults distance themselves from past acquaintances, as is the case with older adults (Rhoades et al., 2018), or move on as part of a more normative developmental stage that occurs for young people (Wood et al., 2018). The findings from this study differ from Padgett’s (2007) sample of older adults who had experienced chronic homelessness and whose next steps tended to focus on making up for lost opportunities. This hopefully suggests young adults who have experienced homelessness can transition into a more normative developmental trajectory through housing interventions such as PSH, rather than becoming another cohort of adults that experience prolonged homelessness (Culhane et al., 2013).

Notable exceptions to our thematic findings, known as negative cases, are also important since not everyone experiences ontological security and improved social relationships, which can be influenced by how PSH is implemented (for example, living alone or with roommates) or the larger neighborhood context and how one’s demographic characteristics fit in with the community. The fact that young adults who experience homelessness also vary in needs is an important consideration, especially when trying to determine the right mix of services. Future research can examine more fully how young adults’ mental health, social networks, and health risk behaviors change as they transition from homeless to PSH (Rhoades et al., 2018), which may depend on the extent to which they experience ontological security.

Strengths and limitations

This study employed many strategies of rigor for qualitative research, including having a robust sample size to ensure rich qualitative data, immersion in the data, co-coding and consensus-driven findings, and negative case analysis (Padgett, 2011). Study limitations include a cross-sectional design rather than having prolonged engagement, and we interviewed young adults living in PSH but do not know how people were selected to be enrolled in these PSH programs. We also did not investigate how these PSH programs were implemented, which could vary and affect participant experiences (Gilmer et al., 2013). There was also important discussion around parenting and mental health that did not “earn” its way into more generalized themes (Charmaz, 2006) but may be important considerations for program implementation. Finally, while the data were robust enough to support a grounded theory, the extent to which this theory helps capture experiences across housing programs for young adults is unknown.

Conclusion

Although more research should focus on client outcomes for young adults in PSH, findings from this study remind us it is important to understand how people experience programs. These experiences may influence longer-term outcomes that result from young adults being engaged during a critical developmental phase, which often is not considered when evaluating program outcomes. Ontological security could ultimately prove to be an important factor that contributes to the success of interventions aimed at helping young adults experiencing homelessness.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01MH110206).

Footnotes

GED = General Equivalency Diploma

Quotes are labeled throughout using participant identification numbers (that is, SP02 is study participant #02).

References

- Arnett Jeffrey Jensen. 2000. “Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties,” American Psychologist 55 (5): 469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett Jeffrey Jensen. 2001. “Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence through midlife,” Journal of Adult Development 8 (2): 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney John, and Boyle Michael H.. 2004. “Home ownership, mortgages and psychological distress,” Housing Studies 19 (2): 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano Richard F., Berglund M. Lisa, Ryan Jean AM, Lonczak Heather S., and Hawkins J. David. 2004. “Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 591 (1): 98–124. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz Kathy. 2006. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative research. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane Dennis P., Metraux Stephen, Byrne Thomas, Stino Magdi, and Bainbridge Jay. 2013. “The age structure of contemporary homelessness: evidence and implications for public policy,” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 13 (1): 228–244. [Google Scholar]

- Curry Susanna R., and Abrams Laura S.. 2015. “They Lay Down the Foundation and Then They Leave Room for Us to Build the House”: A Visual Qualitative Exploration of Young Adults’ Experiences of Transitional Housing,” Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 6 (1): 145–172. doi: 10.1086/680188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curry Susanna R., and Petering Robin. 2017. “Resident Perspectives on Life in a Transitional Living Program for Homeless Young Adults,” Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 34 (6): 507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis Ann, and Thorns David C.. 1998. “Home, home ownership and the search for ontological security,” The Sociological Review 46 (1): 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dworsky Amy, Dillman Keri-Nicole, Dion Robin M., Brandon Coffee-Borden, and Miriam Rosenau. 2012. Housing for youth aging out of foster care: A review of the literature and program typology. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development & Research; (April). [Google Scholar]

- Felitti Vincent J., Anda Robert F., Nordenberg Dale, Williamson David F., Spitz Alison M., Edwards Valerie, Koss Mary P., and Marks James S.. 1998. “Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14 (4): 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz Stephen. 2014. “A Safe and Decent Place to Live: Towards a Housing First framework for youth.” Toronto: Canadian Homelessness Research Network. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Oxford: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer Todd P. 2016. “Permanent supportive housing for transition-age youths: Service costs and fidelity to the housing first model,” Psychiatric Services 67 (6): 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer Todd P., Ojeda Victoria D., Hiller Sarah, Stefancic Ana, Tsemberis Sam, and Palinkas Lawrence A.. 2013. “Variations in Full Service Partnerships and Fidelity to the Housing First Model,” American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 16 (4): 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Harpin Scott B., Murray Amber, Rice Michael, Rames Kendall, and Gilroy Christine. 2016. “Feasibility of a Mental Health Screening and Brief Intervention Shelter Intake Procedure for Runaway/Homeless Youth,” Journal of Adolescent Health 58 (2): S53–S54. [Google Scholar]

- Henwood Benjamin F., Redline Brian, and Rice Eric. 2018. “What do homeless transition-age youth want from housing interventions?” Children and Youth Services Review 89: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns Ade, Hiscock Rosemary, Ellaway Anne, and Macintyre Sally. 2000. “‘Beyond Four Walls’. The Psycho-social Benefits of Home: Evidence from West Central Scotland,” Housing studies 15 (3): 387–410. [Google Scholar]

- Kozloff Nicole, Adair Carol E., Lazgare Luis I. Palma, Poremski Daniel, Cheung Amy H., Sandu Rebeca, and Stergiopoulos Vicky. 2016a. ““Housing first” for homeless youth with mental illness.” Pediatrics: e20161514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozloff Nicole, Stergiopoulos Vicky, Adair Carol E., Cheung Amy H., Misir Vachan, Townley Greg, Bourque Jimmy, Krausz Michael, and Goering Paula. 2016b. “The unique needs of homeless youths with mental illness: baseline findings from a Housing First trial,” Psychiatric Services 67 (10): 1083–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing RD 1965. The divided self. An existential study in madness and sanity. London: Pelican Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mackelprang Jessica L., Harpin Scott B., Grubenhoff Joseph A., and Rivara Frederick P.. 2014. “Adverse outcomes among homeless adolescents and young adults who report a history of traumatic brain injury,” American Journal of Public Health 104 (10): 1986–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccio Elaine M., and Ferguson Kristin M.. 2016. “Services to LGBTQ runaway and homeless youth: Gaps and recommendations,” Children and Youth Services Review 63: 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Milburn Norweeta G., Rice Eric, Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus Shelley Mallett, Rosenthal Doreen, Batterham Phillip, May Susanne J., Witkin Andrea, and Duan Naihua. 2009. “Adolescents exiting homelessness over two years: The risk amplification and abatement model,” Journal of Research on Adolescence 19 (4): 762–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton Matthew H., Dworsky Amy, Matjasko Jennifer L., Curry Susanna R., Schlueter David, Chávez Raúl and Farrell Anne F.. 2018. “Prevalence and correlates of youth homelessness in the United States,” Journal of Adolescent Health 62 (1): 14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson Michelle R., Stanhope Victoria, Small Latoya, and Atterbury Kendall. 2017. ““At times I kinda felt I was in an institution”: Supportive housing for transition age youth and young adults,” Children and Youth Services Review 73: 430–436. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett Deborah K. 2007. “There’s no place like (a) home: Ontological security among persons with serious mental illness in the United States,” Social Science & Medicine 64 (9): 1925–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett Deborah K. 2011. Qualitative and mixed methods in public health.Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett Deborah K., Bikki Tran Smith Benjamin F. Henwood, and Tiderington Emmy. 2012. “Life course adversity in the lives of formerly homeless persons with serious mental illness: context and meaning,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 82 (3): 421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades Harmony, Hsu Hsun-Ta, Rice Eric, Harris Taylor, Wichada LaMotte-Kerr Hailey Winetrobe, Henwood Benjamin, and Wenzel Suzanne. 2018. “Social network change after moving into permanent supportive housing: Who stays and who goes?” Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss Anselm, and Corbin Juliet. 1990. Basics of grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. 2010. Opening Doors: Federal strategic plan to prevent and end homelessness. U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. [Google Scholar]

- Vigilant Lee Garth. 2005. ““I Don’t Have Another Run Left With It”: Ontological Security in Illness Narratives of Recovering on Methadone Maintenance,” Deviant Behavior 26 (5): 399–416. [Google Scholar]

- Wood David, Crapnell Tara, Lau Lynette, Bennett Ashley, Lotstein Debra, Ferris Maria, and Kuo Alice. 2018. “Emerging adulthood as a critical stage in the life course.” In Handbook of Life Course Health Development, Springer, Cham: 123–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional Reading

- Aledort Nina, Hsin Yusyin, Grundberg Susan, and Bolas Jim. 2011. “More than a roof over their heads: A toolkit for guiding transition age young adults to long-term housing success.” The New York City Children’s Plan Young Adult Housing Workgroup (March). http://ccsinyc.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/YoungAdultHousingToolkit1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Roos Leslie E., Mota Natalie, Afifi Tracie O., Katz Laurence Y., Distasio Jino, and Sareen Jitender. 2013. “Relationship between adverse childhood experiences and homelessness and the impact of axis I and II disorders,” American Journal of Public Health 103 (S2): S275–S281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]