Abstract

Why do essentialist beliefs promote prejudice? We proposed that essentialist beliefs increase prejudice toward Black people because they imply that existing social hierarchies reflect a naturally occurring structure. We tested this hypothesis in three studies (N = 621). Study 1 revealed that racial essentialism was associated with increased prejudice toward Blacks among both White and Black adult participants, suggesting that essentialism relates to prejudice according to social hierarchy rather than only to group membership. Studies 2 and 3 experimentally demonstrated that increasing essentialist beliefs induced stronger endorsement of social hierarchy in both Black and White participants, which in turn mediated the effect of essentialism on negative attitudes toward Black people. Together, these findings suggest that essentialism increases prejudice toward low status groups by increasing endorsement of social hierarchies and existing inequality.

Keywords: Race, essentialism, prejudice, intergroup bias, social hierarchy

Humans often view categories as reflecting the underlying natural structure of the environment – a cognitive bias known as psychological essentialism (Gelman, 2003). In the social domain, essentialist thinking can have pernicious implications; essentialism leads people to view members of the same social group (e.g., men, women) as sharing an underlying, inherent nature that causes them to be fundamentally similar in non-obvious, immutable ways (Medin & Ortony, 1989). Although essentialism does not assign positive or negative qualities to particular groupings, it can nevertheless bias intergroup perceptions, leading to prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (e.g., Allport, 1954; Haslam, Rothschild, & Ernst, 2002; Yzerbyt, Corneille, & Estrada, 2001). Indeed, White individuals who believe that race has a biological basis – a core component of essentialist beliefs – exhibit greater prejudice toward Blacks (Jayaratne et al., 2006; Williams & Eberhardt, 2008).

In this research, we considered the possibility that essentialism contributes to prejudice by influencing people’s views of societal structure. We propose that essentialism leads people to believe that social categories reflect objective structure in nature, and thus that observed social hierarchies reflect objective differences in status or value (see also Yzerbyt, Rocher, & Schadron, 1997). From this perspective, essentialism promotes prejudice toward groups at lower levels of social hierarchies regardless of the group membership of the holder of these essentialist beliefs. With regard to race, if essentialism promotes the belief that group status differences reflect objective structure in the world, greater essentialism should predict more negative attitudes toward racial groups that are perceived as low status, because these groups would be viewed as inherently “worse” than high status groups. This would occur regardless of one’s own group membership (e.g., essentialism would lead both White and Black individuals to prefer Whites over Blacks).

By contrast, if essentialism serves primarily to define group boundaries, essentialism should predict more negative attitudes toward outgroups irrespective of their place in the hierarchy (e.g., essentialism would lead White individuals to prefer Whites over Blacks, and Black individuals to prefer Blacks over Whites). Thus, considering how essentialism relates to prejudice in both Black and White Americans may reveal the mechanisms by which essentialism contributes to intergroup attitudes. Further, this work may shed light on why some Black individuals develop negative attitudes toward their own group – a persistent, early-developing pattern (Clark & Clark, 1947; Shutts, 2015) that has negative consequences (Ratner, Halim, & Amodio, 2013; Utsey, Chae, Brown, & Kelly, 2002).

As essentialism is conceptualized as a cognitive bias (e.g., Gelman, 2003; Medin & Ortony, 1989), we predicted it would relate most strongly to cognitive, belief-based expressions of prejudice, as assessed using instruments such as the Attitudes Toward Blacks scale (Brigham, 1993; see also, Modern Racism Scale: McConahay, 1986; Symbolic Racism scale: Henry & Sears, 2002). Such measures assess explicitly held beliefs and construals regarding Black people and their personal, social, and political relationships with White people. Thus, if essentialism affects intergroup attitudes by shaping beliefs about social structures and status differentials, then it should underlie these more explicit, cognitive expressions of prejudice. Cognitive forms of prejudice are dissociable from race-biased affective judgments and implicit associations (Dovidio et al., 1996; Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002; Greenwald, McGhee & Schwartz, 1998; Mann, 1959; Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005), and because essentialism pertains to a cognitive construal of categories, we did not expect it to relate as strongly to such affective or implicit forms of prejudice.

Pretest

Given the various patterns found between essentialism and prejudice in prior research conducted primarily on White adults (e.g., positive relationship: Jayaratne et al., 2006; Williams & Eberhardt; no relationship: Bastian & Haslam, 2006; Bastian, Loughnan, & Koval, 2011; Haslam et al., 2002), and the wide variety of measures used (e.g., Andreychik & Gill, 2014; Haslam et al., 2002; Williams & Eberhardt, 2008), it was important to determine whether the relation between essentialism and prejudice is reliable in White adults using well-validated indices of essentialism and prejudice.

Participants and Procedures.

We recruited 151 participants who self-identified as White (61% female, Mage = 39.1). Participants in all studies were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (AMT). Sample size was determined based on prior studies examining the relation between essentialism and prejudice toward Black people in predominantly White samples (e.g., Williams & Eberhardt, 2008) using G*Power (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009). These power calculations indicated the need for approximately 100 participants per study; we sampled above this number to ensure adequate reliable data. Participants first completed a demographics questionnaire (age, sex, racial-ethnic identity), followed by measures of racial essentialism, implicit prejudice, and explicit prejudice, and were debriefed. Prior to beginning, participants were told that only those meeting the selection criteria would be given access to the full study, but were not told what the selection criteria were. The pretest and Studies 1 and 2 were administered through SocialSci.com, and Study 3 was administered through Qualtrics.

Measures

Racial Essentialism

Participants’ essentialist beliefs about race were assessed with the questionnaire used by Rhodes and Gelman (2009, adapted from Haslam, Rothschild, & Ernst, 2000; see the supplemental online materials). This scale probes multiple components of essentialism, including the naturalness (e.g., race is a natural category), cross-cultural stability (e.g., racial categories are important in all cultures around the world), and inductive potential (e.g., knowing someone’s race tells you a lot about that person) of group membership via 8 items that participants scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Ratings were averaged such that higher composite scores indicated greater racial essentialism1.

Explicit Prejudice

Explicit prejudice toward Blacks was assessed using the Attitudes Toward Blacks scale (ATB; Brigham, 1993), a widely used, highly reliable, and well-understood measure of prejudicial beliefs and attitudes (see Olson & Zabel, 2015) characterized as a cognitive, belief-based expression of prejudice (Dovidio, Esses, Beach, & Gaertner, 2004). Participants rated their agreement, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with each of 20 statements, such as, “I would rather not have Black people live in the same apartment building I live in” and “Some Black people are so touchy about race that it is difficult to get along with them.” Responses were averaged such that higher numbers indicated greater explicit prejudice against Blacks.

Group-based affect

Participants also completed a feelings thermometer (as in Amodio & Devine, 2006), which has been characterized as an affectively-based measure of prejudice (Dovidio et al., 2004). On this measure, participants indicated on a scale of 0 (very cold) to 100 (very warm) how they felt toward African Americans and European Americans, separately and in counterbalanced order2. For each thermometer, a higher value indicated relatively more positive affect toward the focal group, allowing us to examine anti-Black affect independently of pro-White affect.

Implicit Prejudice

Implicit prejudice was assessed using the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald et al., 1998). The IAT measures the strength of mental associations between social categories of White and Black people and positive relative to negative concepts. Following two initial training blocks, in which participants practiced the classification of words and faces separately, participants completed two different types of critical trials (organized in two blocks each). On “compatible” trials, White faces and positive words were classified with one key, and Black faces and negative words were classified with the other key. On “incompatible” trials, Black faces and positive words were classified with one key, and White faces and negative words were classified with the other key. These critical blocks were completed in counterbalanced order and were separated by a face-only training block.

IAT D scores were computed following Amodio and Devine (2006; adapted from Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji, 2003), such that positive scores reflect a relative pro-White/anti-Black association and negative scores reflect a pro-Black/anti-White association. Preliminary analyses revealed that D differed significantly from zero, t(141) = 14.62, p < .001 (M = .50, SD = .41), indicating moderate anti-Black/pro-White bias. Because D scores did not differ as a function of block order, order was not included as a factor in reported analyses.

Exclusions

Data were excluded from analysis if the participant represented extreme values (> 3SD from the mean) on any measure (6); these exclusions yielded a final sample size of 145. Additionally, participants who responded too fast (less than 300 ms) or too slow (greater than 2500 ms) on 10% or more trials on the IAT (3) were excluded from analyses involving the IAT (Greenwald et al., 2003)3.

Results

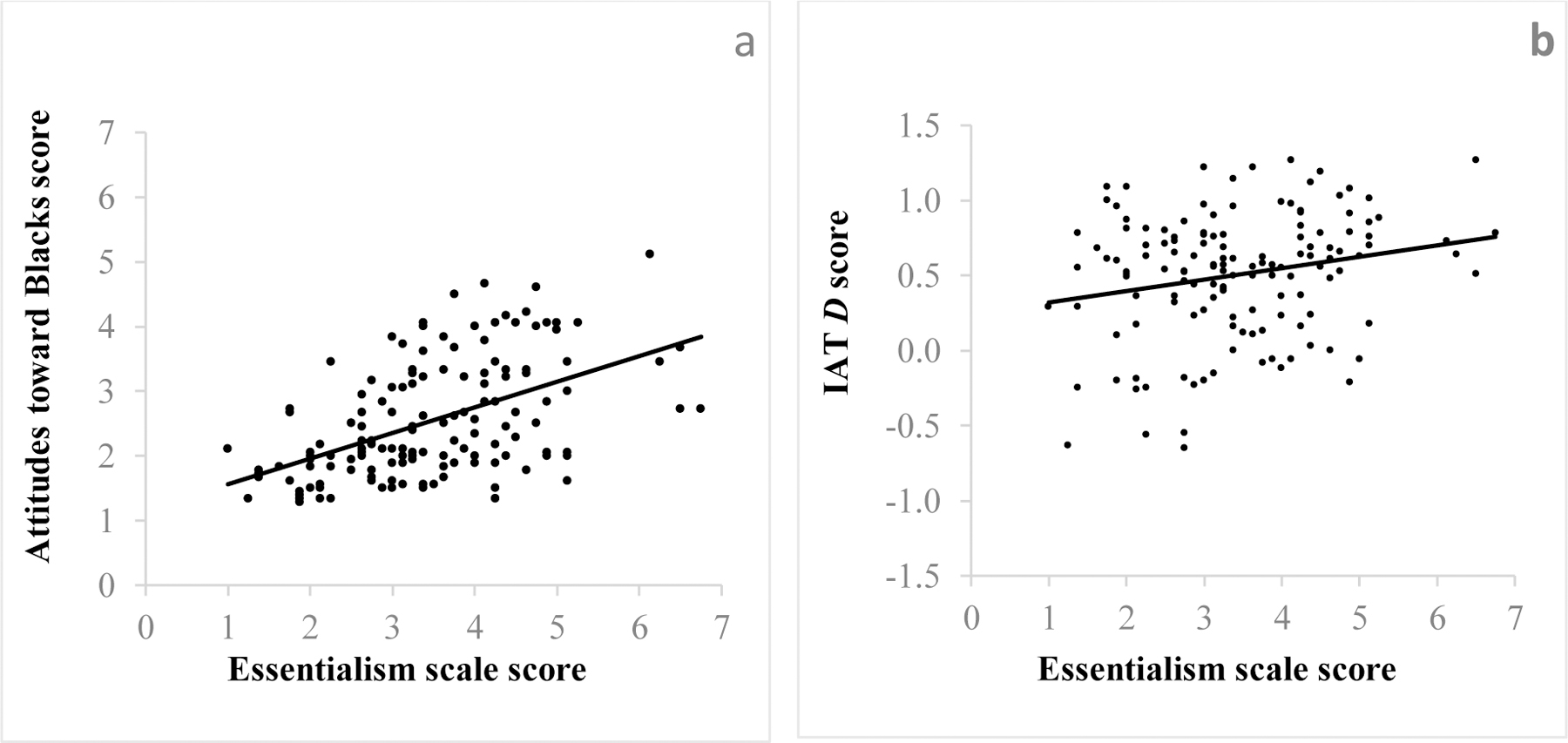

Our central hypothesis was that greater essentialism would be associated with stronger racial prejudice, as assessed by the ATB. Indeed, this pattern emerged, r(145) = .52, p < .001 (Fig. 1a), conceptually replicating previous findings. In exploratory analyses investigating how racial essentialism related to affective dimensions of prejudice, we found that racial essentialism was associated with greater implicit prejudice toward Blacks, r(142) = .22, p = .009 (Fig. 1b). Essentialism was not significantly associated with pro-White, r(145) = .12, p = .15, or pro-Black, r(145) = −.08, p = .34, affect on the feelings thermometers. Although essentialism related to prejudice as assessed by both the ATB and the IAT, it is notable that this effect was larger for the ATB than the IAT, z = 2.96, p = .003.

Figure 1.

Relationships between racial essentialism and prejudice on tasks assessing (a) negative belief-based attitudes (ATB scores) and (b) implicit cognition (IAT) among White participants (N = 145). Higher values indicate greater racial essentialism and greater prejudice toward Blacks.

Discussion

Consistent with previous research in predominantly White samples (e.g., Jayaratne et al., 2006; Williams & Eberhardt, 2008), stronger endorsement of essentialist beliefs was correlated with prejudiced attitudes, as measured by a cognitive, belief-based measure, and was also modestly associated with implicit evaluation. This finding provided a foundation for an analysis that included Black participants.

STUDY 1

In Study 1 we tested the relation between racial essentialism and prejudice toward Blacks among both Black and White participants. If essentialism, as hypothesized, leads to prejudice by strengthening the belief that social hierarchies reflect objective structure to the world, then racial essentialism should relate to greater belief-based prejudice toward low status groups regardless of participants’ race.

Participants and Procedures

Participants included 294 adults who self-identified either as African American/Black (n = 142) or White (n = 152; Black: 63% female, Mage = 33.6; White: 61% female, Mage = 39.6). Across Studies 1–3, those who did not self-identify as White or as African American/Black were not able to participate further. Participants completed the same measures as in the pretest, and our primary outcome variable was ATB score. Although we found no relationship between essentialism and an affective measure of prejudice (i.e., feelings thermometers) in the pretest, we included feelings thermometers in all subsequent studies to explore whether essentialism related to this form of prejudice in Black participants (Study 1) or whether it varied in response to experimental manipulation of essentialism (Studies 2 and 3; see supplemental online materials for analyses). Data were excluded if scores were extreme (greater than 3 standard deviations from the mean) on any variable (5 Black, 4 White), yielding a final sample of 285 (Black n = 137, White n = 148).

Results

Preliminary analyses (Table 1) revealed that Black participants exhibited more racial essentialism than White participants. White participants expressed marginally greater prejudice toward Blacks on the ATB, yet, on average, ATB scores for White and Blacks were both below the scale midpoint (reflecting relatively low prejudice overall). Although White participants also expressed greater implicit prejudice toward Blacks on the IAT compared with Black participants, it is notable that the Black participants’ degree of anti-Black implicit bias was also significant, t = 2.92, p = .004, d = .50.

Table 1.

Means and Independent t-Test Results for Black and White participants in Study 1.

| Black Participants mean (SD) (n = 137) | White Participants mean (SD) (n = 148) | t | p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essentialism Scale | 3.78(1.29) | 3.43(1.14) | −2.44 | .01 | .29 |

| Attitudes Toward Blacks Scale | 2.27(.71) | 2.43(.83) | 1.80 | .07 | .21 |

| Implicit Association Test | .10(.41) | .46(.38) | 7.61 | <.001 | .90 |

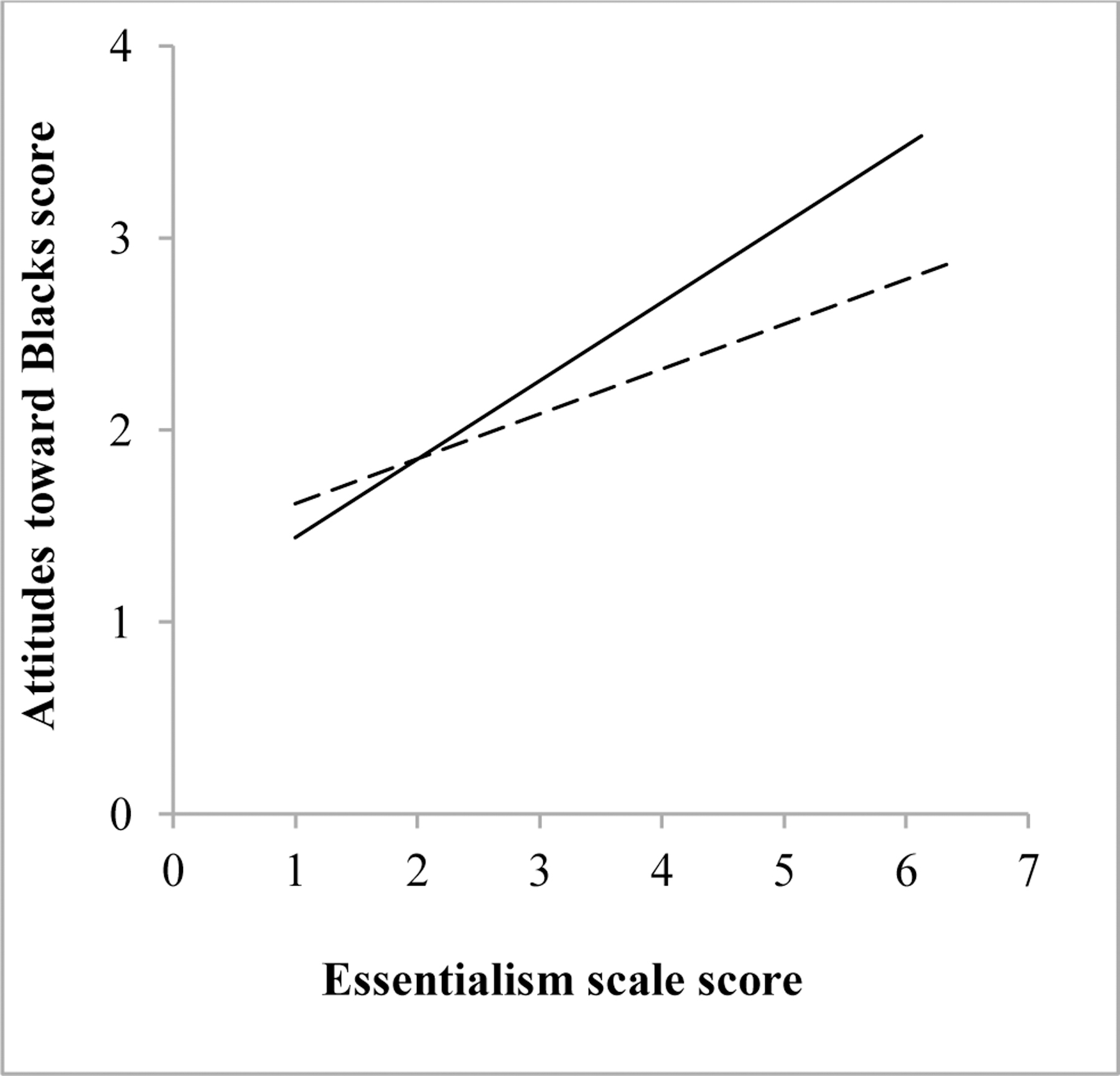

Using regression analysis, we next tested the main and interactive effects of participant race (−1 Black; 1 White) and essentialism on each measure of prejudice. In our focal analysis of ATB scores, both main effects were significant: White participants expressed more explicit prejudice toward Blacks than Black participants, β = .18, p = .001, and, more importantly given the present questions, essentialism was related to explicit prejudice, β = .50, p < .001. The interaction was also significant, β = .14, p = .008 (Fig. 2); simple slope analyses revealed that essentialism significantly related to greater prejudice among both White, β = .56, p < .001, and Black, β = .43, p < .001, participants, but that the magnitude of this effect was greater for Whites. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that essentialist thinking relates to prejudice toward Black Americans by enhancing endorsement of social hierarchies.

Figure 2.

Relationship between racial essentialism and prejudice on belief-based attitudes toward Blacks (ATB predicted values from regressions) in White (n = 148) and Black (n = 137) participants. Higher values indicate greater racial essentialism and greater prejudice toward Blacks. The solid line indicates White participants and dashed line indicates Black participants.

In the analysis of IAT score, the only significant effect was for participant race, β = .42, p < .001. No effects emerged for essentialism, β = .07, p = .22, or the interaction, β = .06, p = .26. However, when data for White and Black participants are analyzed separately, we found a marginal relationship between essentialism and IAT D score in White participants, consistent with Study 1, β = .14, p = .09, and no relationship for Black participants, β = .005, p = .95.

Discussion

In this study essentialism related to more negative attitudes toward Blacks, as assessed by the ATB, among both White and Black participants, providing preliminary support for the possibility that essentialism increases prejudice toward low status groups (regardless of a participant’s own group membership) by strengthening the beliefs that status differences reflect objective structure in the world. We next moved on to experimental tests of this hypothesis.

STUDY 2

In Study 2, we conducted a direct test of our hypothesis by examining the causal effects of essentialism on both prejudice and endorsement of social hierarchies by experimentally manipulating essentialist beliefs. If essentialism promotes the belief that social groups and hierarchies reflect objective, unchangeable structure in the world, then this view should be expressed in terms of increased hierarchy endorsement (see also Jost & Burgess, 2000; Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). Thus, we tested whether increasing the salience of essentialist beliefs leads to increased hierarchy endorsement and whether hierarchy endorsement mediates the effect of essentialism on prejudicial attitudes.

Participants and Procedures

We recruited 219 participants who self-identified as African American/Black (n = 111, 67% female, Mage = 32.1) or White (n = 108, 52% female, Mage = 37.2).

Essentialism manipulation

After completing a demographics form, participants were randomly assigned to a pro- or anti-essentialism condition and asked to read one of two fictional science news articles about the biological basis of race (adapted from Williams and Eberhardt, 2008; see also Chen & Hamilton, 2012). Participants were told the study concerned how technical information is conveyed to non-scientists via the media. Participants were randomly assigned to read either a pro-essentialism (“Scientists pinpoint genetic underpinnings of race”) or anti-essentialism (“Scientists reveal that race has no genetic basis”) article. Upon completion, they answered an attention check question.

Measures

Participants completed a Social Dominance Orientation-6 Scale (SDO-6; Pratto et al., 1994; see also Jost & Thompson, 2000), which assessed participants’ endorsement of the social hierarchy. The scale included 16 items (e.g., “It’s probably a good thing that certain groups are at the top and other groups are at the bottom”), which participants rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). These ratings were averaged such that higher scores indicated greater hierarchy endorsement. Participants then completed the dependent measures used in Study 1.

Exclusions

Data were excluded if the participant failed the attention check (11 Black, 16 White), exceeded the typical time to complete the study (1 White), or represented extreme values on any of the dependent variables within a given condition (1 Black, 4 White), yielding a final sample size of 188 (Black n = 99, White n = 89).

Results

Effects of essentialism on hierarchy endorsement and prejudice.

A series of two-way ANOVAs were conducted to determine the effects of essentialism condition (anti- or pro-essentialism) and participant race (White or Black) on hierarchy endorsement and prejudice toward Blacks. As predicted, hierarchy endorsement was increased in the pro-essentialism condition (MPro = 2.30, SDPro = 1.00) relative to the anti-essentialism condition (MAnti = 1.90, SDAnti = .86, F(1,184) = 9.07, p = .003, ηp2 = .05). There were no main, F(1,184) = 1.00, p = .32, ηp2 = .005, or interactive, F(1,184) = .68, p = .41, ηp2 = .004, effects of participant race, indicating that pro-essentialism information led to greater endorsement of social hierarchies among both White and Black participants.

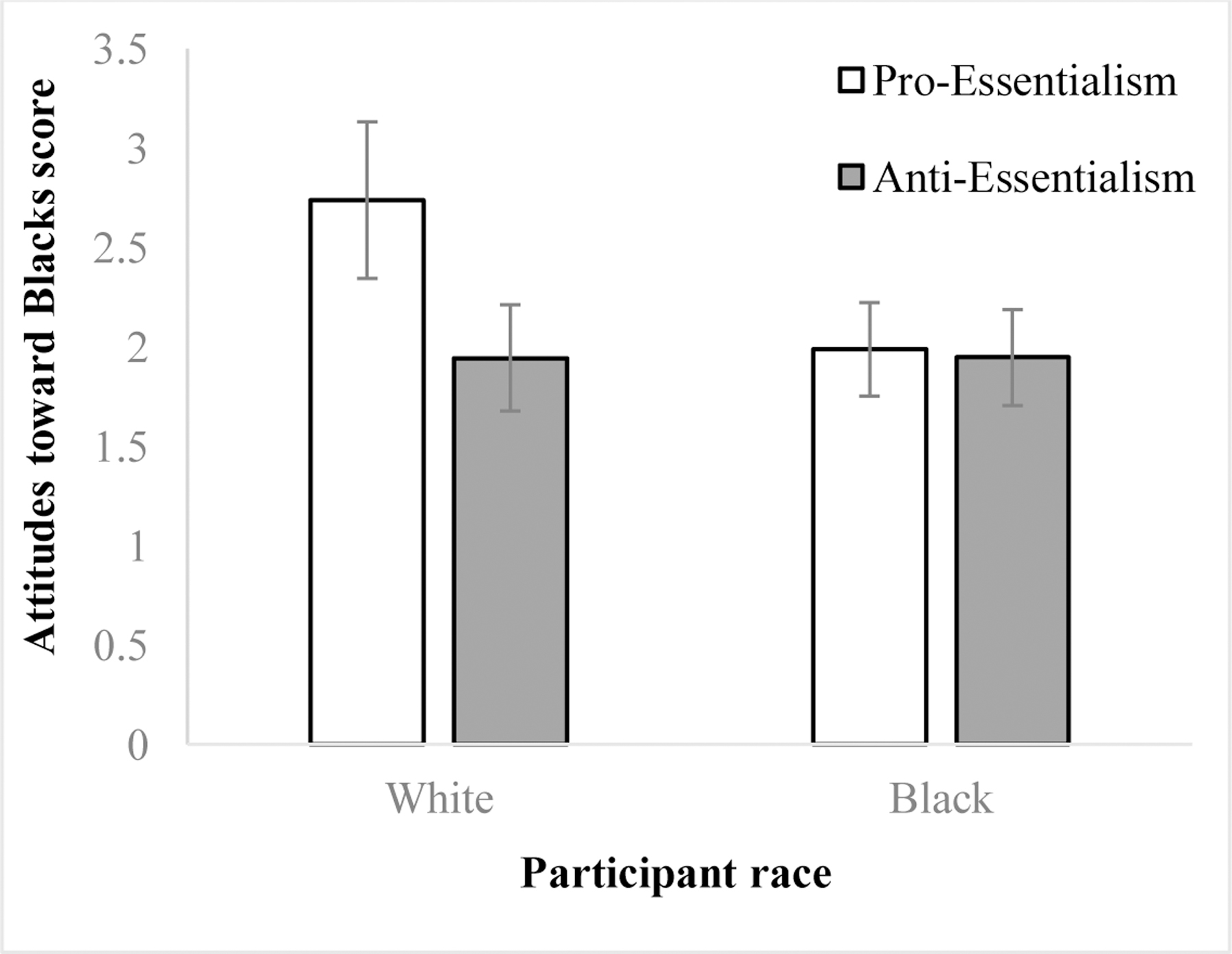

On the ATB, White participants (MWhite = 2.34, SDWhite = 1.18) expressed greater prejudice toward Blacks than did Black participants (MBlack = 1.97, SDBlack = .83), F(1,184) = 6.84, p = .01, ηp2 = .04. In support of our hypothesis, participants in the pro-essentialism condition (MPro = 2.33, SDPro = 1.14) expressed greater prejudice than those in the anti-essentialism condition (MAnti = 1.94, SDAnti = .84), F(1, 184) = 8.51, p = .004, ηp2 = .04. The interaction was also significant, F(1, 184) = 6.89, p = .009, ηp2 = .04 (Figure 3); pairwise comparisons indicated that White participants in the pro-essentialism condition (MPro = 2.74, SDPro = 1.31) reported substantially more explicit prejudice than Whites in the anti-essentialism condition (MAnti = 1.94, SDAnti = .88), F(1, 184) = 14.60, p < .001, ηp2 = .11. By contrast, there was no effect of essentialism condition on attitudes for Black participants, F(1, 184) = .04, p = .83, ηp2 = .001. That is, the manipulation of essentialism affected ATB scores of White participants but not those of Black participants.

Figure 3.

Effects of participant race and condition on explicit prejudice, assessed by the ATB, for White and Black participants in Study 2 (N = 188). Error bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals.

On the IAT, D scores were higher among White (MWhite = .46, SDWhite = .39) than Black (MBlack = .12, SDBlack = .48) participants, F(1,182) = 26.56, p < .001, ηp2 = .13. However, there were no main, F(1,182) = .60, p = .44, ηp2 = .003, or interactive, F(1,182) = .35, p = .55, ηp2 = .002, effects of essentialism.

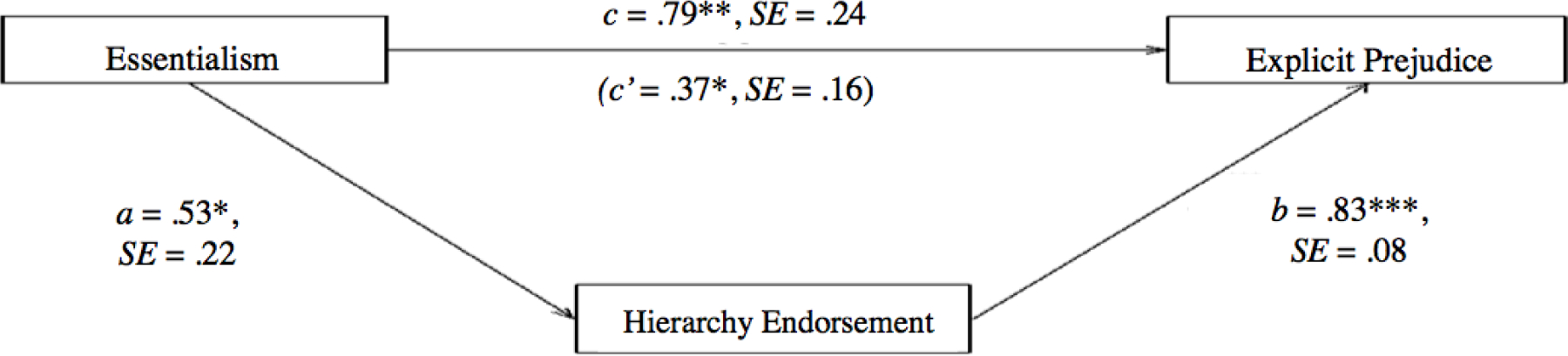

Mediation analysis.

Because the essentialism manipulation influenced prejudiced attitudes on the ATB only among white participants, we tested our proposed mediation model among White participants only, using the PROCESS bootstrapping macro (Hayes, 2012), with 2000 times resampling. A 95th percentile confidence interval was computed to test the significance of the indirect effect.

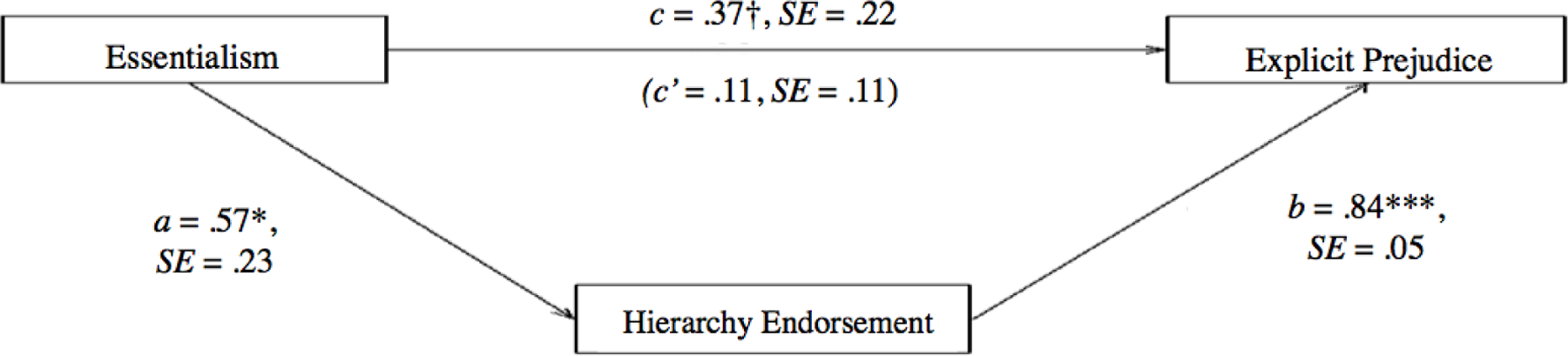

As noted above, essentialism was a significant predictor of hierarchy endorsement, b = .53, SE = .22, t = 2.40, p = .02, as well as ATB scores, b = .79, SE = .24, t = 3.34, p = .001. Moreover, hierarchy endorsement was associated with ATB scores, b = .85, SE = .08, t = 11.03, p < .001. When essentialism and hierarchy endorsement were both included in an analysis predicting ATB scores, hierarchy endorsement was a significant predictor, b= .81, SE = .08, t = 10.37, p < .001, above and beyond essentialism, b = .37, SE = .16, t = 2.25, p = .03. Importantly, a test of mediation indicated a significant indirect effect, 95% CI [.08, .82], κ2 = .21 (Preacher & Kelley, 2011), consistent with the hypothesis that essentialism increases prejudice by enhancing hierarchy endorsement (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Hierarchy endorsement mediated the relationship between essentialism and explicit prejudice, as measured by the ATB scale, for White participants (N = 89). Unstandardized regression coefficients for simple mediation analysis (Model 4) are presented. †p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Discussion

Study 2 revealed that essentialism causally increased prejudice by enhancing endorsement of social hierarchies. Among all participants, the induction of essentialism led to greater endorsement of social hierarchies, and, in White participants, to stronger prejudice toward Blacks. These findings provide new evidence that the manipulation of essentialist thinking can alter belief-based prejudice. Furthermore, the effect of essentialism on prejudice in White participants was mediated by changes in hierarchy endorsement, providing initial support for the hypothesis that essentialism increases prejudice toward Blacks by increasing endorsement of existing social hierarchies.

A limitation of Study 2 was the lack of essentialism effects on anti-Black attitudes among Black participants. Although it is possible that Black people’s attitudes toward Blacks are more resistant to change because they are tightly bound to one’s self-identity, it was also the case that Study 2’s design may have limited our ability to detect essentialism’s effects on prejudice toward Blacks as assessed by the ATB measure, especially among Black participants. One weakness of the design was that participants completed the IAT before the ATB. The experience of completing the IAT could affect how participants expressed their attitudes toward Blacks on the ATB (i.e., being exposed to Black and White photo stimuli might have increased attention to the racial focus of this study, causing participants—particularly Black participants—to more carefully monitor their responses on the ATB). Additionally, the effects of our subtle essentialism manipulation, already anticipated to be relatively weak in Black participants, might not have been strong enough to produce detectable changes on multiple dependent measures. Therefore, to increase our ability to detect any potential effect of essentialism on prejudice among Black participants and provide a stronger test of the hypothesis that essentialism increases anti-Black prejudice by increasing hierarchy endorsement, Study 3 was streamlined to include only key measures. That is, we omitted the IAT, given that the IAT can be taxing and draws attention to race, and thus it might have diluted the effects of the manipulation 4.

STUDY 3

In Study 3, we examined the causal effects of essentialism on prejudice and hierarchy endorsement among Black participants. We tested whether the effect of essentialism on negative attitudes toward Blacks in Black participants is mediated by increased endorsement of social hierarchies, as we found for White Americans in Study 2.

Participants and Procedures

We recruited 108 participants who self-identified as African American/Black (67% female, Mage = 30.2). Participants completed a demographics form, were randomly assigned to a pro- or anti-essentialism condition, and then completed the measure to assess hierarchy endorsement, followed by the ATB.

Data were excluded from analysis if the participant failed the attention check (9) or represented extreme values on any of the dependent variables within a given condition (1). These exclusions yielded a final sample size of 98.

Results

Effects of essentialism on hierarchy endorsement and prejudice.

As in Study 2, a one-way ANOVA produced a significant effect of essentialism on hierarchy endorsement scores, F(1,96) = 6.40, p = .013, ηp2 = .06, such that scores in the pro-essentialism condition (MPro = 2.69, SDPro = 1.22) were higher than those in the anti-essentialism condition (MAnti = 2.11, SDAnti = .99).

A separate one-way ANOVA on ATB scores revealed a marginal effect of essentialism, F(1,96) = 2.88, p = .09, ηp2 = .03, such that the pro-essentialism condition produced stronger anti-Black prejudice (MPro = 2.56, SDPro = 1.14) than the anti-essentialism condition (MAnti = 2.19, SDAnti = 1.01). Although marginal, this effect is consistent with the correlational pattern observed in Study 2 for Black participants, as well as the effect of essentialism on anti-Black attitudes among White participants in Study 2.

Mediation analysis.

Although the direct effect of essentialism on ATB scores was marginal, it was possible that essentialism might indirectly influence participants’ attitudes through changes in hierarchy endorsement. Thus, we tested for a pattern of mediation as in Study 2. This analysis revealed that essentialism predicted hierarchy endorsement scores, b = .57, SE = .23, t = 2.53, p = .01, and marginally predicted ATB scores, b = .37, SE = .17, t = 1.72, p = .09. Furthermore, hierarchy endorsement was associated with ATB scores, b = .82, SE = .05, t = 17.34, p < .001. When essentialism and hierarchy endorsement were both included in the model predicting ATB scores, the effect for hierarchy endorsement remained significant, b= .84, SE = .05, t = 17.38, p < .001, but the effect for essentialism was no longer significant, b = −.11, SE = .11, t = −1.00, p = .32. Importantly, a test of the indirect effect was significant, 95% CI [.11, .85], κ2 = .34, suggesting that, as with the White participants of Study 2, hierarchy endorsement mediated the relation between essentialism and explicit ATB prejudice in Black adults (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Endorsement of the social hierarchy mediated the relationship between essentialism and explicit prejudice, as measured by the ATB scale, for Black participants in Study 3 (N = 98). Unstandardized regression coefficients for simple mediation analysis (Model 4) are presented. †p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Discussion

Study 3 confirmed that essentialism causally relates to hierarchy endorsement in Black participants, replicating the pattern observed in Study 2. The induction of essentialist beliefs led to marginally more negative attitudes on the ATB in Black participants, revealing that essentialist thinking can influence attitudes toward Blacks even among Black individuals. Moreover, a test of mediation produced a significant indirect effect of essentialism on racial attitudes through changes in hierarchy endorsement. By demonstrating this pattern among Black participants, these data provide strong support for the hypothesis that essentialism increases prejudice toward lower status groups by increasing endorsement of social hierarchies.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The present research investigated the processes through which essentialism leads to prejudice. In particular, we considered the possibility that essentialism influences not just beliefs about individuals and groups but also beliefs about how groups are arranged in the social hierarchy (e.g., Yzerbyt et al., 1997). According to this hypothesis, essentialism should relate to greater prejudice toward Blacks among both Black and White perceivers given the lower relative status of African Americans in American society. Indeed, racial essentialism was associated with increased belief-based forms of prejudice toward Black people in White participants (Studies 1 and 2) and Black participants (Studies 1 and 3), and this effect occurred by increasing participants’ endorsement of social hierarchies (Studies 2 and 3). Moreover, by manipulating essentialist beliefs in Studies 2 and 3, these results revealed a causal effect of essentialism on social hierarchy endorsement, which in turn explained the effect of essentialism on prejudice. These findings suggest that by leading individuals to view social hierarchies as objectively determined and natural, essentialism increases the tendency to endorse, and perhaps perpetuate, existing hierarchies through continued prejudice toward lower status social groups.

Our research additionally offers a new explanation for why Black individuals sometimes express negative attitudes toward their own group. That is, essentialism – a domain-general cognitive tendency that does not directly pertain to attitudes – can be readily applied to beliefs about race in a way that may lead Black individuals to devalue their racial group through endorsement of social hierarchies. Although an experimental test of this proposed mediator would clarify the hypothesized process (as in Guimond, Dambrun, Michinov, & Duarte, 2003; Kteily, Sidanius, & Levin, 2011), these studies suggest a novel theoretical account for how essentialism may perpetuate anti-Black prejudice. By elucidating the role of hierarchy endorsement, our findings identify an unexamined source of Black ingroup devaluation and suggest a new approach to buffering Black individuals from its effects. Moreover, while this study focused on anti-Black attitudes, the links between essentialist beliefs, hierarchy endorsement, and negative attitudes toward lower-status social groups suggests that this general framework might explain negative attitudes toward other social groups perceived to be low status as well.

Although our findings demonstrate that essentialism can lead to more negative attitudes toward minorities among both White and Black individuals, essentialism is a multifaceted construct that could relate to more positive attitudes toward one’s own racial group, regardless of that group’s social status. Holding a strong, positive racial identity has been associated with improved behavioral and physiological outcomes (e.g., academic achievement: Altschul, Oyserman, & Bybee, 2006; mental health: Sellers, Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006; physiology: Ratner et al., 2013). Although the links between essentialist beliefs and positive racial identity have not been established, increased essentialism may relate to more positive racial identity given that essentialism comprises, in part, the beliefs that category membership is stable and indicative of ingroup similarity. In this case, in addition to increasing endorsement of social hierarchies, essentialism could bolster ingroup identity, perhaps explaining why we found a smaller relation between essentialism and anti-Black prejudice in Black than White participants. Our understanding of how and when essentialism affects intergroup attitudes will benefit from study on how specific facets of essentialism affect particular forms of intergroup attitudes.

More broadly, this research demonstrates the implications of essentialism for anti-Black prejudice, extending the theoretical scope of how essentialism affects intergroup attitudes, by affecting perceptions and beliefs about social hierarchies. Furthermore, while past work suggests that reducing essentialism should reduce prejudice, our findings reveal that a consideration of social structures, and a group’s place within them, is needed to best utilize essentialism-based interventions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

In addition to our primary measure of essentialism, we also used three additional measures of essentialism for exploratory purposes for future studies aiming to compare racial essentialism in children and adults: the visitor task (Rhodes & Gelman, 2009; Kalish, 1998) and the switched at birth task (Hirschfeld, 1995), commonly used in developmental research, and the Race Conceptions Scale (RCS: Williams & Eberhardt, 2008). Exploratory analyses demonstrated that our primary measure of essentialism was positively correlated with the RCS, r(145) = .64, p < .001, as well as the visitor task, r(145) = .16, p = .05.

After rating African and European Americans, participants were asked to complete two additional feelings thermometers for Asian and Latino Americans, separately and in counterbalanced order. Participants ratings on these thermometers were not analyzed for this study.

Across all studies, results did not change significantly from those presented here when excluded participants were included in analyses.

As expected, ATB scores were significantly higher in in the streamlined procedure in Study 3 (M: 2.40; SD: 1.09) than in Study 2 (M: 1.97; SD: .83), F(1,202) = 9.93, p = .002, ηp2 = .05, supporting the concern that IAT completion may have reduced the sensitivity of the subsequently-administered ATB.

REFERENCES

- Allport GW (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul I, Oyserman D, & Bybee D (2006). Racial-ethnic identity in mid-adolescence: Content and change as predictors of academic achievement. Child Development, 77, 1155–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodio DM, & Devine PG (2006). Stereotyping and evaluation in implicit race bias: Evidence for independent constructs and unique effects on behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 652–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreychik MR & Gill MJ. (2014). Do natural kind beliefs about social groups contribute to prejudice? Distinguishing bio-somatic essentialism from bio-behavioral essentialism and both of these from entiativity. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 18, 454–474. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian B, & Haslam N (2006). Psychological essentialism and stereotyping endorsement. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian B, Loughnan S, & Koval P (2011). Essentialist beliefs predict automatic motor-responses to social categories. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14, 559–567. [Google Scholar]

- Brigham JC (1993). College students’ racial attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 1933–1967. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JM, & Hamilton DL (2012). Natural ambiguities: Racial categorization of multiracial individuals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Clark KB & Clark MP (1947). Racial identification and preference among negro children In Hartley EL (Ed.), Readings in Social Psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Brigham JC, Johnson BT, & Gaertner SL (1996). Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination: Another look In Macrae CN, Stangor C, & Hewstone M (Eds.), Stereotypes and stereotyping (pp. 276–319). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Kawakami K, & Gaertner SL (2002). Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF , Esses VM, Beach KR, & Gaertner SL (2004). The role of affect in determining intergroup behavior: The case of willingness to engage in intergroup contact In Mackie DM & Smith ER (Eds.), From prejudice to intergroup emotions: Differentiated reactions to social groups. Philadelphia: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, & Lang A-G (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA (2003). The essential child: Origins of essentialism in everyday thought. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, & Schwartz JKL (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1464–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, & Banaji MR (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimond S, Dambrun M, Michinov N, & Duarte S (2003). Does social dominance generate prejudice? Integrating individual and contextual determinants of intergroup cognitions. Journal of personality and social psychology, 84, 697–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N, Bastian B, Bain P, & Kashima Y (2006). Psychological essentialism, implicit theories, and intergroup relations. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 9, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N, Rothschild L, & Ernst D (2002). Are essentialist beliefs associated with prejudice? British Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N, Rothschild L, & Ernst D (2000). Essentialist beliefs about social categories. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Hirschfeld LA (1995). Do children have a theory of race? Cognition, 54, 209–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry PJ, & Sears DO (2002). The symbolic racism 2000 scale. Political Psychology, 23, 253–283. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaratne TE, Ybarra O, Sheldon JP, Brown TN, Feldbaum M, Pfeffer CA, & Petty EM (2006). White Americans’ genetic lay theories of race differences and sexual orientation: Their relationship with prejudice toward Blacks, and gay men and lesbians. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 9, 77–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, & Banaji MR (1994). The role of stereotyping in system‐justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, & Burgess D (2000). Attitudinal ambivalence and the conflict between group and system justification motives in low status groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, & Thompson EP (2000). Group-based dominance and opposition to equality as independent predictors of self-esteem, ethnocentrism, and social policy attitudes among African Americans and European Americans. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 209–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kalish CW (1998). Natural and artificial kinds: Are children realists or relativists about categories? Developmental Psychology, 34, 376–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kteily NS, Sidanius J, & Levin S (2011). Social dominance orientation: Cause or ‘mere effect’?: Evidence for SDO as a causal predictor of prejudice and discrimination against ethnic and racial outgroups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Mann JH (1959). The relationship between cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects of racial prejudice. Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- McConahay JB (1986). Modern racism, ambivalence, and the Modern Racism Scale In Dovidio J & Gaertner S (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 91–126). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medin DL, & Ortony A (1989). Psychological essentialism In Vosniadou S & Ortony A (Eds.), Similarity and Analogical Reasoning, pp. 179–195. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- No S, Hong Y, Liao H, Lee K, Wood D, & Chao MM (2008). Lay theory of race affects and moderates Asian Americans’ responses toward American culture. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 991–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson MA, & Zabel KL (2015). Measures of prejudice In Nelson TD (Ed.), Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination (pp. 175–212). New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto F, Sidanius J, Stallworth LM & Malle BF (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741–763. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Kelley K (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16, 93–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratner KG, Halim ML, & Amodio DM (2013). Perceived stigmatization, ingroup pride, and immune and endocrine activity: Evidence from a Black and Latina community sample. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, & Gelman S (2009). A developmental examination of the conceptual structure of animal, artifact, and human social categories across two cultural contexts. Cognitive Psychology, 59, 244–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, & Lewis RL (2006). Racial identity matters; The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescents, 16, 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Shutts K (2015). Young children’s preferences: Gender, race, and social status. Child Development Perspectives, 9, 262–266. [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR & Pettigrew TF (2005). Differential relationships between intergroup contact and affective and cognitive dimensions of prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1145–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Chae MH, Brown CF, & Kelly D (2002). Effect of ethnic group membership on ethnic identity, race-related stress, and quality of life. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8, 366–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MJ, & Eberhardt JL (2008). Biological conceptions of race and the motivation to cross racial boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 1033–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yzerbyt V, Corneille O, & Estrada C (2001). The interplay of subjective essentialism and entitativity in the formation of stereotypes. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5, 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yzerbyt V, Rocher S, & Schadron G (1997). Stereotypes as explanations: A subjective essentialistic view of group perception In Spears R, Oakes PJ, Ellemers N, & Haslam SA (Eds.), The social psychology of stereotyping and group life (pp. 20–50). Cambridge: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.