Abstract

Commensal non-pathogenic Neisseria spp. live within the human host alongside the pathogenic Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae and due to natural competence, horizontal gene transfer within the genus is possible and has been observed. Four distinct Neisseria spp. isolates taken from the throats of two human volunteers have been assessed here using a combination of microbiological and bioinformatics techniques. Three of the isolates have been identified as Neisseria subflava biovar perflava and one as Neisseria cinerea . Specific gene clusters have been identified within these commensal isolate genome sequences that are believed to encode a Type VI Secretion System, a newly identified CRISPR system, a Type IV Secretion System unlike that in other Neisseria spp., a hemin transporter, and a haem acquisition and utilization system. This investigation is the first to investigate these systems in either the non-pathogenic or pathogenic Neisseria spp. In addition, the N. subflava biovar perflava possess previously unreported capsule loci and sequences have been identified in all four isolates that are similar to genes seen within the pathogens that are associated with virulence. These data from the four commensal isolates provide further evidence for a Neisseria spp. gene pool and highlight the presence of systems within the commensals with functions still to be explored.

Keywords: Neisseria subflava, Neisseria cinerea, bacterial capsule, T6SS, natural competence for transformation

Data Summary

Sequence data for commensal Neisseria spp. investigated are available in GenBank under the following accession numbers: Neisseria subflava strains M18660 (NZ_CP031251; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_CP031251.1); ATCC 49275 (NZ_CP039887; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_CP039887.1); NJ9703 (NZ_ACEO00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_ACEO00000000.2); C2012011976 (NZ_POXP00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POXP00000000.1); C2011004960 (NZ_POXK00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POXK00000000.1); C2009010520 (NZ_POXD00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POXD00000000.1); C2011020198 (NZ_POXM00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POXM00000000.1); C2005001510 (NZ_POWU00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POWU00000000.1); C2014021188 (NZ_POYB00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POYB00000000.1); C2011020199 (NZ_POXN00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POXN00000000.1); C2011033015 (NZ_POXO00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POXO00000000.1); C2008002238 (NZ_POXC00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POXC00000000.1); C2011009653 (NZ_POXL00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POXL00000000.1); C2007002879 (NZ_POWV00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POWV00000000.1); C2008001664 (NZ_POXB00000000; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_POXB00000000.1); Neisseria mucosa strain FDAARGOS_260 (NZ_CP020452; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_CP020452.2); Neisseria flavescens ATCC 13120 (NZ_CP039886; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_CP039886.1); Neisseria cinerea strain NCTC10294 (NZ_LS483369; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_LS483369.1). Sequence data for Neisseria meningitidis strains investigated are available in GenBank under the following accession numbers: MC58 (AE002098.2; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AE002098.2); FAM18 (NC_008767.1; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_008767.1); Z2491 (AL157959.1; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AL157959.1). Sequence data for Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains investigated are available in GenBank under the following accession numbers: FA1090 (AEOO4969.1; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AE004969.1); NCCP11945 (CP001050.1; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/CP001050.1). Sequence data for Neisseria lactamica strains investigated are available in GenBank under the following accession numbers: 020–06 (NC_014752.1; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_014752.1). The authors confirm all supporting data, code and protocols have been provided within the article or through supplementary data files.

Impact Statement.

To date, most research into Neisseria spp. has focused on the pathogens Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae , but many commensal non-pathogens of this genus contain gene repertoires that are worthy of investigation, including those associated with virulence in the pathogens. Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) has been demonstrated between Neisseria spp. The sequences revealed in this investigation are therefore potential sources of genetic material for the pathogens via HGT. Acquisition of the capsule genes described here by N. meningitidis could result in capsule switching and enable circumvention of serogroup-specific vaccines. In combination with alleles for vaccine targets fHbp and NadA, potential exists for vaccine escape via HGT from these commensal genomes and other sequences in the circulating gene pool. The data presented here provide further evidence for a wide and varied Neisseria spp. gene pool and emphasize the presence of numerous ‘virulence genes’ within the commensal species, requiring the functions of these to be re-evaluated. This research additionally highlights the presence of previously unexplored systems within the commensal Neisseria spp. with functions still to be explored, which may lead to the development of novel therapeutic interventions with regard to pathogen-related infections.

Introduction

The human oral, nasal, and pharyngeal cavities are inhabited by hundreds of different bacterial species, with the throat possessing a greater number than any other body site [1]. The most common isolates from this site in humans belong to the phyla Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Spirochaetes, and Proteobacteria, with Proteobacteria contributing to around 17 % of the overall microbiome [2]. Of the β-Proteobacteria, the family Neisseriaceae comprise Gram-negative coccoid bacteria with a preference for colonizing mucosal surfaces within the nasopharyngeal and oral cavities of humans [3]. These micro-organisms are considered to be a major constituent of the core microbiome of the oral cavity [2] and contribute significantly to the normal flora at these sites [3].

Overall the genus Neisseria is composed of a number of species, including two pathogens, Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae , and non-pathogenic species such as Neisseria lactamica , Neisseria cinerea , Neisseria elongata , Neisseria flavescens , Neisseria mucosa , Neisseria polysaccharea , Neisseria sicca , Neisseria weaveri , Neisseria animaloris , Neisseria bacilliformis , Neisseria zoodegmatis , Neisseria oralis , Neisseria canis , Neisseria shayeganii, and Neisseria subflava biovars flava, perflava, and subflava [4]. Commensal Neisseria are normally harmless, although some have been identified as opportunistic pathogens and have caused rare cases of sepsis and meningitis [3, 5]. Virulence in N. meningitidis is mediated by a number of factors, including the expression of a range of adhesins, lipooligosaccharide endotoxins (LOS), a polysaccharide capsule for evasion of the host immune response, and iron acquisition systems [6]. While capsule genes are often associated with N. meningitidis , they have also been identified within the non-pathogenic Neisseria spp. [7].

Despite iron being essential [8], iron acquisition within a host is considered to be a major virulence determinant and vital to pathogenesis in N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae [9]. Low iron levels are known to exert a bacteriostatic effect over most invading bacteria and the human host exploits this by maintaining low concentrations of free iron within serum and its secretions via iron-binding proteins [10]. Many micro-organisms have evolved to overcome the selective pressure of iron-limited environments and Neisseria spp. are known to possess a wide range of mechanisms for its acquisition [11]. It is believed that diversity in iron uptake genes aids colonization of different Neisseria spp. within the same niche, where host antibodies are targeted towards a variety of iron acquisition components from different bacterial species [12].

While some strains of N. meningitidis have an invasive capacity [13], invasive, disseminated N. gonorrhoeae infections are rare. Pathogenic Neisseria are most often associated with their own niche environments, with N. gonorrhoeae being associated with infections of the mucosa within the genital tract and N. meningitidis being associated with the nasopharynx. Despite this being the case, site of infection does not provide an accurate way to identify Neisseria spp. [14]. Over the past few decades, cases of N. meningitidis isolated from the genital tract mucosa have increased [14, 15] and similarly, cases of N. gonorrhoeae isolated from the oropharynx have increased [16, 17]. Indeed, several recent cases of difficult to treat extensively drug resistant (XDR) gonococcal infections, included pharyngeal infection [18, 19]. With regards to the nasopharyngeal and oral cavities in humans, commensal Neisseria have been isolated co-colonizing alongside the pathogens N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae . It is believed that through co-colonization and a natural competence for transformation [20], many of the pathogenic and commensal Neisseria now share a significant pool of genetic material with one another and many commensals can be identified as containing most of the virulence genes associated with the pathogens [21].

The pathogenic and commensal Neisseria spp. occupy the same niches and as a result of their common ancestry, in combination with sharing of genetic material, possess high levels of similarity across their genomes [22, 23]. An analysis across commensal and pathogenic neisserial genomes carried out by Maiden and Harrison [24] highlighted these similarities, with N. lactamica and N. meningitidis being found to share a set of core genes that contribute to around 60 % of their overall genome size. In addition, widespread horizontal genetic transfer between human Neisseria species has been seen through comparative genomic analysis [12], and pili in commensal N. elongata have been demonstrated to be involved in interspecies gene transfer with N. gonorrhoeae [25].

Current molecular identification techniques often struggle to distinguish clearly between different bacterial groups in this genus [26], although identification to the level of genus can be achieved through the examination of specific genes or groups of genes. Ribosomal genes are often chosen for identification as they tend to be highly conserved throughout evolution. While phylogenetic grouping using 16S rRNA gene sequences can aid in species identification, issues have arisen when using this method alone due to different species, including Neisseria spp., possessing very similar or identical 16S rRNA genes [24]. Analysis of a set of core genes found across all bacteria through Ribosomal Multilocus Sequence Typing (rMLST) has been shown to be a more efficient and rapid method than 16S rRNA typing for bacterial species identification [24].

In this study, four Neisseria spp. were isolated from the throats of human volunteers. These were classified using microbiological techniques and their genome sequences were compared against other commensal and pathogenic Neisseria . The genomic sequences of these four isolates display a high level of similarity to commensal Neisseria spp., although analysis of their genomic sequences has highlighted the presence of sequences classified as virulence genes when present in the pathogens, including capsule, pilus, and LOS, as well as a number of non-pilus adhesins more commonly associated with pathogenic Neisseria spp. Specific gene clusters have also been identified that are believed to encode a newly identified CRISPR system, a type VI secretion system, a type IV secretion system different from that in the Gonococcal Genetic Island [27, 28], a hemin transporter, and a haem acquisition and utilization system. The data presented in this study provide further evidence for a diverse and varied gene pool within Neisseria spp. and highlight the presence of gene clusters within these isolates with functions still to be explored.

Methods

Bacterial isolation

Isolates were obtained by sweeping the back of the throat with a sterile cotton tipped swab and then plating immediately onto GC agar (Oxoid) with Kellogg’s [29] and 5 % Fe(NO3)3 supplements. Shortly after collection, plates were incubated at 37 °C in a candle tin overnight. KU isolates came from sampling 64 student volunteers on 3 separate occasions in the Spring of 2012. RH isolates came from sampling six student volunteers on four separate occasions from October 2012 to January 2013. From the mixed bacterial cultures obtained, replica plates were taken using a Scienceware replica plater and sterile velveteen. Two replica plates were taken, one to create a freezer stock and one to select individual colonies for isolation. These were incubated overnight at 37 °C in a candle tin. The following day, all growth from one plate was frozen at −80 °C and from the other plate individual colonies were picked onto fresh GC agar with supplements for individual isolation. After overnight growth, cultures were Gram-stained and tested for catalase and oxidase activity. Gram-negative, oxidase-positive, catalase-positive cultures were archived at −80 °C locally and at the National Collection of Industrial Food and Marine Bacteria (NCIMB, Aberdeen).

Identification of Neisseria species

Four suspected Neisseria spp. isolates were grown on GC agar plates (Oxoid) with Kellogg’s [29] and 5 % Fe(NO3)3 supplements at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. Control species for India ink staining, Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis , were grown on nutrient agar (Oxoid) and incubated at 37 °C. Blood agar (Oxoid) included 7 % defibrinated horse blood (Oxoid) to test for haemolytic activity. API NH strips (bioMérieux) to identify the species were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Nitrate Reduction Test (Sigma) was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions to identify samples capable of reducing nitrates.

Genome sequencing

DNA was extracted from the four isolates by scraping the growth from a GC agar plate into 500 µl of GC broth and extracting the DNA using the Puregene Yeast/Bacterial kit (Qiagen). This extracted DNA was dried down and sent to the MicrobesNG service (microbesng.uk) for Illumina sequencing. The sequence data were processed through SPAdes [30] to generate de novo-assembled contigs that were automatically annotated using Prokka [31] according to the standard MicrobesNG pipeline. The contigs were also submitted to RAST [32–34] and to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline [35] (software revision 3.3). These automated annotations were compared in Artemis [36] and the NCBI annotation was chosen for use and submission to GenBank: KU1003-01 [37]; KU1003-02 [38]; RH3002v2f [39]; RH3002v2g [40]. Genome sequence data were analysed using rMLST [41], the NCBI 16S blast tool (blastn against the 16S ribosomal RNA sequences database) [42], CRISPRminer [43], CRISPRFinder [44], nucleotide blast [42], clustal Omega [45], and SecRet6 [46].

Genome sequence analysis

The PubMLST Genome Comparator tool v2.6.2 [47] was used to compare 38 completed Neisseria spp. genome sequences and those of KU1003-01, KU1003-02, RH3002v2f, and RH3002v2g. In total, 3023 loci were compared across all genomes, with the following parameters: minimum 70 % identity, minimum 50 % alignment, blastn word size 20, and 80 % core threshold. The resulting distance matrix output was loaded into SplitsTree4 [48] in nexus format to generate a neighbour-joining cladogram. Virulence genes [21] within the genome sequences of the four isolates were identified using progressive Mauve v2.3.1 at default settings [49]. The NCBI-generated annotation files containing the DNA sequence of each of the isolate’s contigs were aligned against N. subflava strain M18660 [50], N. mucosa strain FDAARGOS_260 [51], N. flavescens strain ATCC 13120 [52], N. cinerea strain NCTC10294 [53], N. meningitidis strains MC58 [54], FAM18 [55], and Z2491 [56], N. gonorrhoeae strains FA 1090 [57] and NCCP11945 [58], and N. lactamica strain 020–06 [59]. Virulence genes from the pathogen genome sequences were identified in Mauve using the sequence navigator and aligned to reveal the presence of homologous sequences where present in the isolates. Additional investigations used a set of 15 N . subflava strains [50, 60–73].

Results and discussion

Microbiological identification

The four isolates collected from human throat swab cultures were identified as being oxidase- and catalase-positive Gram-negative diplococci. Two isolates, KU1003-01 and KU1003-02, came from the same individual and were collected on the same occasion. The other two isolates, RH3002v2f and RH3002v2g, also came from a single volunteer and were collected on the same occasion. No other Gram-negative oxidase- and catalase-positive isolates were identified. The concurrent collection of these isolates supports co-colonization of this human niche with more than one neisserial species at a time, as proposed by Yazdankhah and Caugant [74].

Isolate KU1003-01 presented as large, smooth, round, and moist colonies on GC agar producing a yellowish pigment and having a glistening surface. Isolate KU1003-02 presented as medium, round, and slightly granular colonies on GC agar producing a yellowish pigment and having a rough surface. Isolate RH3002v2f presented as small, round, unpigmented colonies with a glistening surface. Isolate RH3002v2g presented as medium, round, and smooth pigmented colonies with a glistening surface.

None of the isolates were determined to be haemolytic; a lack of haemolysis on blood agar indicated that the isolates did not belong to the haemolytic species N. animaloris [75]. Nitrate reduction testing for all four isolates gave negative results, indicating the isolates could not be N. mucosa , N. oralis , N. canis , N. shayeganii , N. wadisworthii, or N. elongata subspecies nitroreducens [76]. All four isolates grew at 35 °C, indicating that they were not N. gonorrhoeae , according to the API NH growth criteria [76]. A control N. gonorrhoeae strain NCCP11945 culture did not grow under these conditions. API NH results indicated that the best identification of three of the isolates was as Neisseria spp. (Table 1). Isolate RH3002v2f is most likely to be Neisseria cinerea, based on the result of the API NH test, growth at 35 °C, and its translucent and glistening appearance [77].

Table 1.

Isolate identification using API NH, rMLST, and 16S blast analysis

|

Isolate |

API NH results |

rMLST |

Top 16S blast hit (NCBI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

KU1003-01 |

Neisseria spp. |

N. flavescens, N. mucosa, N. subflava |

N. perflava (99 %, E value 0.0) |

|

KU1003-02 |

Neisseria spp. |

N. perflava (99 %, E value 0.0); N. cinerea (99%, E value 0.0)) |

|

|

RH3002v2f |

N. cinerea (99 %, E value 0.0); N. meningitidis (99 %, E value 0.0) |

||

|

RH3002v2g |

Neisseria spp. |

N. flavescens, N. mucosa, N. subflava |

N. perflava (99 %, E value 0.0) |

Genome sequencing and assembly

Genome sequencing and assembly for all four isolates was carried out by MicrobesNG. Illumina Mi-seq short reads were de novo assembled into contiguous sequences using SPades. The assembly of sequence reads for KU1003-01 generated 58 contigs with a total genome size of 2 345 197 bp [37]. Isolate KU1003-02 assembled into the greatest number of contigs at 73. Despite this, the overall genome size for this isolate is on a par with the size of its co-isolate at 2 303 261 bp [38]. Isolate RH3002v2f contains the smallest of the three genomes at 1 953 373 bp, which assembled in 26 contigs [39]. By comparison, its co-isolate RH3002v2g has a genome size of 2 193 423 bp across 42 contigs [40].

Genome sequence-based identification

Neisseria spp. share common ancestry, occupy the same niche, and are able to share genetic material. As a direct result, Neisseria spp. display high levels of similarity across their genomes [22, 23]. Current molecular identification techniques often struggle to distinguish clearly between different bacterial groups [26] and difficulties can arise when assigning Neisseria to particular species groups due to their genetic similarity [26].

Analysis of the genome sequence data through rMLST and 16S blast suggested a range of Neisseria spp. for the four isolates (Table 1). While 16S rRNA analysis was able to classify the isolates used in this study as Neisseria spp., the results of the rMLST indicated varying results with regard to their identification as one particular species. The result of rMLST for isolate KU1003-01 indicated that it was either N. flavescens , N. mucosa , or N. subflava , but the top 16S blast hit suggested N. perflava , which is a biovar of N. subflava (Table 1). For KU1003-02, rMLST indicated that it was N. mucosa , whilst the 16S disagreed, suggesting N. perflava or N. cinerea (Table 1). Analysis of RH3002v2f through rMLST indicated that this isolate was N. cinerea and 16S homology also suggested N. cinerea or N. meningitidis . Therefore, the sequence-based results support the laboratory results, suggesting that this isolate is N. cinerea (Table 1). The fourth isolate, RH3002v2g, produced the same rMLST and 16S rRNA blast results as KU1003-01, suggesting that it was either N. flavescens , N. mucosa , or N. subflava , and N. perflava ( N. subflava biovar perflava), respectively (Table 1).

Signatures of DNA Uptake Sequences (DUSs) support species assignments

In the pathogenic Neisseria spp., the spread and increased levels of antibiotic resistance, as well as the evolution of pathogenesis, are as a direct result of their ability to take up and transform DNA from their environment [23, 74, 78, 79].

To identify and locate DUSs, the four isolate genome sequences were subjected to frequent character analyses as described by Davidsen et al. [80]. Within the KU1003-01 genome sequence data, 2009 copies of DUS variant 1 (DUSvar1) [81] were identified. DUSvar1 is also referred to as AG-DUS [82]. Within the KU1003-02 genome sequence data, 2393 copies of DUSvar1/AG-DUS were identified and within RH3002 v2g, 1957 copies of DUSvar1/AG-DUS were identified (Table 2). DUSvar1/AG-DUS are most often associated with N. subflava , N. flavescens, and N. elongata [81, 82]. The dialects in neisserial DUS signatures are known to vary in a species-specific manner [12, 81, 82]. There are 2024 copies of DUSvar1/AG-DUS in N. subflava strain M18660, for example [Data Citation 5]. A significantly lower number of DUS variant 2 (DUSvar2), also known as AG-mucDUS, associated with N. mucosa and N. sicca [81, 82], were identified in these three isolates (Table 2). These data support the assignment of isolates KU1003-01, KU1003-02, and RH3002v2g to N. subflava biovar perflava. The classical DUS described by Berry et al. [81] and designated AT-DUS by Frye et al. [82] is associated with N. meningitidis , N. gonorrhoeae , N. lactamica, and N. cinerea . This was the most frequent DUS identified within isolate RH3002v2f, at 1158 copies, and this result is consistent with the API NH and rMLST data for this isolate belonging to the species N. cinerea .

Table 2.

The type and number of DUSs within sequenced isolates and their best match genome sequences for comparison

|

|

ATGCCGTCTGAA |

AGGCCGTCTGAA |

AGGTCGTCTGAA |

|---|---|---|---|

|

KU1003-01 |

140 |

2009 |

99 |

|

KU1003-02 |

172 |

2393 |

107 |

|

RH3002 vg |

137 |

1909 |

83 |

|

147 |

2024 |

98 |

|

|

RH3002 vf |

1158 |

202 |

74 |

|

N. cinerea NCTC10294 |

1198 |

212 |

80 |

Comparative genome sequence analysis

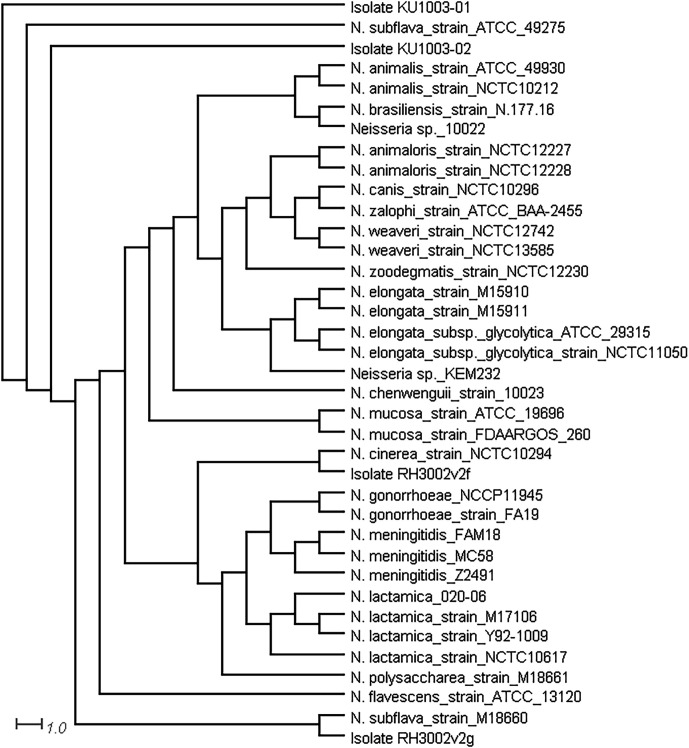

To further support the species assignments, phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the genomic sequences of the isolates, compared to complete genome sequence data from 38 Neisseria spp. in the PubMLST database on Neisseria.org [ 47]. The output was visualized using SplitsTree4 [48], which showed that isolates KU1003-01 and KU1003-02 clustered with N. subflava strain ATCC 49275, RH3002v2g with N. subflava strain M18660, and RH3002v2f with N. cinerea strain NCTC10294 (Fig. 1). This adds another level of support to our species assignments for these isolates.

Fig. 1.

Neighbour-joining cladogram tree of the four Neisseria spp. isolates sequenced. Generated using the PubMLST Genome Comparator tool at Neisseria.org [47] and SplitsTree4 [[48]] with the complete genome sequences of 38 Neisseria spp. and the sequence data from isolates KU1003-01, KU1003-02, RH3002v2f, and RH3002v2g.

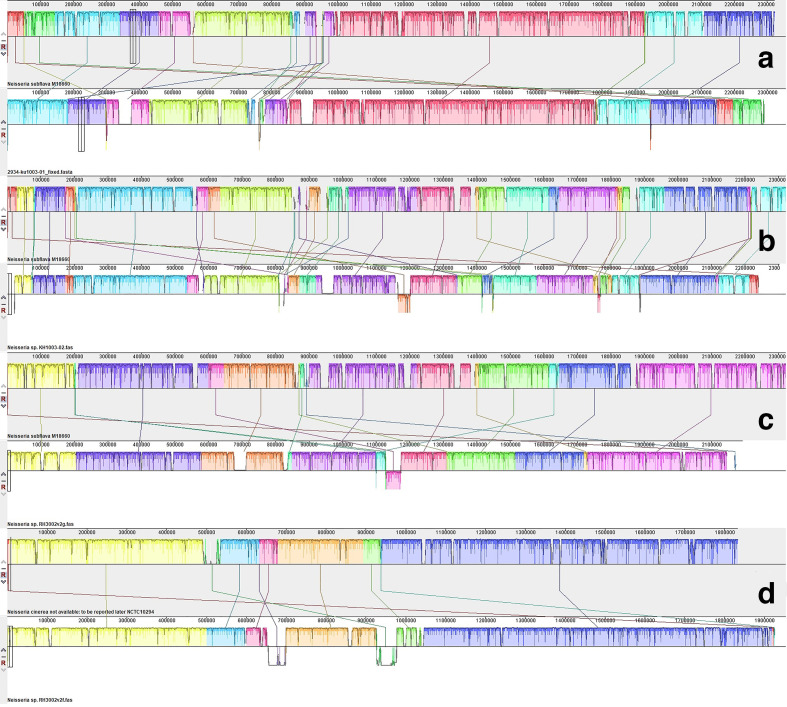

The genome sequences and annotations for each of the four isolates, KU1003-01, KU1003-02, RH3002v2f, and RH3002v2g, were imported into Mauve and compared against commensal Neisseria spp. reference sequences to identify and align homologous regions. To facilitate comparative analyses between the genomes, the contigs for each isolate were reordered against a reference genome believed to be most similar to the isolate using the Mauve contig mover (MCM) tool (Fig. 2). KU1003-01, KU1003-02, and RH3002 v2g aligned closely to the completed genome for N. subflava M18660 [50] rather than N. mucosa strain FDAARGOS_260 [51] or N. flavescens strain ATCC 13120 [52]. RH3002v2f aligned closely to the completed genome for N. cinerea NCTC 10294 [53]. These alignments strongly support KU1003-01, KU1003-02, and RH3002 v2g being N. subflava biovar perflava, and RH3002 v2f being N. cinerea , agreeing with the laboratory and other genetic analyses. Comparisons between the co-isolated genomes also indicated that despite originating from the same host, KU1003-01 and KU1003-02, identified as N. subflava biovar perflava, came from two distinct lineages.

Fig. 2.

Whole-genome progressive Mauve pairwise alignments of ordered contigs against complete genome sequences that are similar to those of the isolates. Blocks that are the same colour between the aligned pairs show regions of genome sequence data that share homology. Three of the isolates aligned well to the complete genome sequence for N. subflava strain M18660, as shown in pairs A (KU1003-01 and N. subflava strain M18660), B (KU1003-02 and N. subflava strain M18660), and C (RH3002v3g and N. subflava strain M18660). One isolate, RH3002v2f, aligned well with N. cinerea NCTC10294, as in pair D.

Genome sequence comparison is considered to be an effective tool for identifying putative virulence genes [83] and regions of difference between species. Mauve alignments against N. meningitidis strains MC58 [54], FAM18 [55], and Z2491 [56], N. gonorrhoeae strains FA 1090 [57] and NCCP11945 [58], and N. lactamica strain 020–06 [59] were used to assess similarities with other Neisseria spp. reference sequences, including the pathogens. These comparisons revealed regions of similarity for further investigation (Table 3), as well as regions of difference that were also investigated (Table 4), some of which were unique to a particular isolate.

Table 3.

A comparison of the presence of virulence genes across the isolates

|

Virulence factors |

Related genes |

Neisseria spp. KU1003-01 |

Neisseria spp. KU1003-02 |

Neisseria spp. RH3002v2f |

Neisseria spp. RH3002v2g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adherence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adhesion and penetration protein |

app/hap |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

LOS sialylation |

lst |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

LOS synthesis |

lgtA |

np |

np |

BBW69_00125 |

np |

|

lgtB |

np |

np |

BBW69_00130 |

np |

|

|

lgtC |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

lgtD |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

lgtE |

np |

np |

BBW69_00135 |

np |

|

|

lgtF |

np |

BBP28_02055 |

BBW69_04775 |

np |

|

|

lgtG |

np |

np |

BBW69_09635, BBW69_09640‡ |

np |

|

|

rfaK |

np |

BBP28_02060 |

BBW69_04770 |

np |

|

|

rfaF |

BBW80_07160 |

BBP28_02020 |

BBW69_06390 |

BBP27_02875 |

|

|

kdtA/waaA |

BBW80_02890 |

BBP28_00140 |

BBW69_08680 |

BBP27_08930 |

|

|

rfaC |

BBW80_03315 |

BBP28_01425 |

BBW69_08770 |

BBP27_00620 |

|

|

rfaD* |

BBW80_06690 |

BBP28_07150 |

BBW69_01995 |

BBP27_00270 |

|

|

rfaE * |

BBW80_06685 |

BBP28_07145 |

BBW69_01990 |

BBP27_00265 |

|

|

lpxA * |

BBW80_02940 |

BBP28_00185 |

BBW69_08210 |

BBP27_04090 |

|

|

lpxB * |

BBW80_02935 |

BBP28_00180 |

BBW69_08320 |

BBP27_04085 |

|

|

lpxD * |

BBW80_02950 |

BBP28_00195 |

BBW69_08220 |

BBP27_04100 |

|

|

pgm * |

BBW80_07200 |

BBP28_01980 |

BBW69_01850 |

BBP27_02915 |

|

|

misR * |

BBW80_10070 |

BBP28_05700 |

BBW69_00920 |

BBP27_05185 |

|

|

misS * |

BBW80_10075 |

BBP28_05695 |

BBW69_00915 |

BBP27_05190 |

|

|

fabZ * |

BBW80_02945 |

BBP28_00190 |

BBW69_08215 |

BBP27_04095 |

|

|

kdsA |

BBW80_07275 |

BBP28_00980 |

BBW69_02905 |

BBP27_03005 |

|

|

kdsB |

BBW80_03730 |

BBP28_07120 |

BBW69_01220 |

BBP27_00240 |

|

|

Neisseria adhesion A NadA |

nadA |

BBW80_10475 |

† |

np |

BBP27_04320 |

|

Type IV pili |

pilC1 |

BBW80_01810 |

BBP28_10510 |

BBW69_04085 |

BBP27_07165 |

|

pilC2 |

np |

np |

BBW69_04075 |

np |

|

|

pilE |

BBW80_10385 |

BBP28_05385 |

BBW69_08575 |

BBP27_05490 |

|

|

pilS |

BBW80_10390 |

BBP28_05390 |

np |

BBP27_05495 |

|

|

pilD |

BBW80_01845 |

BBP28_10475 |

BBW69_05880 |

BBP27_07235 |

|

|

pilF |

BBW80_01835 |

BBP28_10485 |

BBW69_05895 |

BBP27_07225 |

|

|

pilG |

BBW80_01840 |

BBP28_10480 |

BBW69_05875 |

BBP27_07230 |

|

|

pilX |

BBW80_07320 |

BBP28_01030 |

BBW69_07215 |

BBP27_03050 |

|

|

pilW |

BBW80_07325 |

BBP28_01035 |

BBW69_07210 |

BBP27_03055 |

|

|

pilM |

BBW80_06120 |

BBP28_04890 |

BBW69_05370 |

BBP27_05990 |

|

|

pilN |

BBW80_06125 |

BBP28_04895 |

BBW69_05375 |

BBP27_05985 |

|

|

pilO |

BBW80_06130 |

BBP28_04900 |

BBW69_05380 |

BBP27_05980 |

|

|

pilP |

BBW80_06135 |

BBP28_04905 |

BBW69_05385 |

BBP27_05975 |

|

|

pilQ |

BBW80_06140 |

BBP28_04910 |

BBW69_05390 |

BBP27_05970 |

|

|

pilT |

BBW80_03545 |

BBP28_03915 |

BBW69_08555 |

BBP27_04600 |

|

|

pilT2 |

BBW80_03550 |

BBW80_03550 |

BBW69_08560 |

BBP27_04605 |

|

|

pilU |

BBW80_09540 |

BBP28_08495 |

BBW69_01715 |

BBP27_08040 |

|

|

pilH |

BBW80_07335 |

BBP28_01045 |

BBW69_07200 |

BBP27_03065 |

|

|

pilV |

BBW80_07330 |

BBP28_01040 |

BBW69_07205 |

BBP27_03060 |

|

|

pilZ |

BBW80_03840 |

BBP28_07015 |

BBW69_01725 |

BBP27_00140 |

|

|

Pilus-associated genes |

pglA * |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

pglB * |

np |

np |

BBW69_05440 |

np |

|

|

pglB2 * |

BBW80_06065 |

BBP28_04835 |

np |

BBP27_09005 |

|

|

pglB2b * |

BBW80_06060 |

BBP28_04830 |

np |

BBP27_09000 |

|

|

pglC * |

BBW80_06045 |

BBP28_04815 |

BBW69_05445 |

BBP27_09025 |

|

|

pglD * |

BBW80_06040 |

BBP28_04810 |

BBW69_05450 |

BBP27_09030 |

|

|

pglE * |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

pglF* |

BBW80_06085 |

BBP28_04855 |

BBW69_05425 |

BBP27_08985 |

|

|

pglG * |

BBW80_06075 |

BBP28_04845 |

BBW69_05430 |

BBP27_08995 |

|

|

pglH * |

BBW80_06070 |

BBP28_04840 |

BBW69_05435 |

BBP27_09000 |

|

|

Efflux pump systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

FarAB |

farA |

BBW80_10400 |

BBP28_04660 |

BBW69_05945 |

BBP27_04245 |

|

farB |

BBW80_10395 |

BBP28_04655 |

BBW69_05940 |

BBP27_04240 |

|

|

MtrCDE |

mtrC |

BBW80_00055 |

BBP28_10630 |

BBW69_04715 |

BBP27_01915 |

|

mtrD |

BBW80_00060 |

BBP28_10625 |

BBW69_04720 |

BBP27_01910 |

|

|

mtrE |

BBW80_00065 |

BBP28_10620 |

BBW69_04725 |

BBP27_01905 |

|

|

mtrR * |

BBW80_00050 |

BBP28_10635 |

BBW69_04710 |

BBP27_01920 |

|

|

Immune evasion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Capsule |

ctrA |

BBW80_02740 |

BBP28_10005 |

np |

BBP27_08790 |

|

ctrB |

BBW80_02735 |

BBP28_10000 |

np |

BBP27_08785 |

|

|

ctrC |

BBW80_02730 |

BBP28_09995 |

np |

BBP27_08780 |

|

|

ctrD |

BBW80_02725 |

BBP28_09990 |

np |

BBP27_08775 |

|

|

lipA |

BBW80_08850 |

BBP28_09040 |

np |

BBP27_03705 |

|

|

lipB |

BBW80_08845 |

BBP28_09045 |

np |

BBP27_03710 |

|

|

siaA / synA |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

siaB/synB |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

siaC/synC |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

siaD/synD |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

synE |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

mynA / sacA |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

mynB/sacB |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

mynC/sacC |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

mynD/sacD |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

Immune modulators |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Factor H binding |

fHbp |

BBW80_06745 |

np |

BBW69_06045 |

np |

|

Neisserial surface protein A |

nspA |

np |

np |

BBW69_01155 |

np |

|

Invasion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Class 5 outer protein |

opc |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

Opacity protein |

opa |

np |

np |

BBW69_01160 |

np |

|

PorA |

porA |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

PorB |

porB |

BBW80_10465 |

BBP28_04620 |

BBW69_04225 |

BBP27_04310 |

|

Other surface proteins |

omph * |

BBW80_02955 |

BBP28_00200 |

BBW69_08225 |

BBP27_04105 |

|

omp85 * |

BBW80_02960 |

BBP28_00205 |

BBW69_08230 |

BBP27_04110 |

|

|

Heparin-binding antigen NHBA |

nhba |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

Iron uptake systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ABC transporter |

fbpA |

np |

np |

BBW69_01085 |

np |

|

fbpB |

np |

np |

BBW69_01080 |

np |

|

|

fbpC |

np |

np |

BBW69_01075 |

np |

|

|

Ferric enterobactin transport protein A/ferric-repressed protein B |

fetA / frpB |

BBW80_05725 |

BBP28_00435 |

BBW69_09195 |

BBP27_09310 |

|

Haemoglobin receptor |

hmbR |

BBW80_00620 |

BBP28_10830 |

np |

BBP27_01375 |

|

Haem uptake |

hpuA |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

hpuB |

np |

np |

BBW69_08435 |

np |

|

|

Lactoferrin-binding protein |

lbpA |

np |

np |

BBW69_01315 |

np |

|

lbpB |

np |

np |

BBW69_01310 |

np |

|

|

Ton system |

tonB |

BBW80_02960 |

BBP28_00205 |

BBW69_08230 |

BBP27_04110 |

|

exbB |

BBW80_01265 |

BBP28_01625 |

BBW69_04660 |

BBP27_06930 |

|

|

exbD |

BBW80_01260 |

BBP28_01620 |

BBW69_04665 |

BBP27_06925 |

|

|

Transferrin-binding protein |

tbpA |

BBW80_03495 |

BBP28_03865 |

BBW69_08600 |

BBP27_04660 |

|

tbpB |

BBW80_04640 |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

Other iron acquisition genes |

bcp * |

BBW80_04540 |

BBP28_06595 |

BBW69_01630 |

BBP27_09650 |

|

bfrA * |

BBW80_08395 |

BBP28_02745 |

BBW69_03245 |

BBP27_06475 |

|

|

bfrB * |

BBW80_08400 |

BBP28_02740 |

BBW69_03240 |

BBP27_06480 |

|

|

hemH * |

BBW80_04410 |

BBP28_06720 |

BBW69_01460 |

BBP27_09780 |

|

|

Protease |

|

|

|

|

|

|

IgA protease |

Iga |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

Stress proteins |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Catalase |

katA |

BBW80_05740 |

BBP28_00450 |

BBW69_04130 |

BBP27_09245 |

|

Manganese transport system |

mntA |

BBW80_00475 |

BBP28_10980 |

BBW69_00885 |

BBP27_01220 |

|

mntB |

BBW80_00480 |

BBP28_10975 |

BBW69_00880 |

BBP27_01225 |

|

|

mntC |

BBW80_00485 |

BBP28_10970 |

BBW69_00875 |

BBP27_01230 |

|

|

Methionine sulphoxide reductase |

msrA / msrB (pilB) |

BBW80_03270 |

BBP28_01380 |

BBW69_08590 |

BBP27_00665 |

|

Recombinational repair protein |

recN |

BBW80_04510 |

BBP28_06620 |

BBW69_01565 |

BBP27_09675 |

|

Toxin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

RTX toxin |

frpA |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

frpC |

np |

np |

np |

np |

|

|

Two comp reg sys |

basR |

BBW80_06160 |

BBP28_04930 |

BBW69_05315 |

BBP27_05950 |

|

basS |

BBW80_06155 |

BBP28_04925 |

BBW69_05310 |

BBP27_05955 |

|

|

Cell separation |

nlpD |

BBW80_08360 |

BBP28_02780 |

BBW69_06215 |

BBP27_06440 |

|

Nitric oxide reductase |

norB |

BBW80_04740 |

BBP28_06390 |

BBW69_06810 |

BBP27_01665 |

*Previously reported as pathogen-specific.

†nadA homologue of Yersinia yadA was predicted by RAST as a partial gene at the end of 2 contigs

‡Two adjacent CDSs align.

np, not present.

Table 4.

Specific regions of difference identified across the four isolates

|

Isolate |

Annotated CDSs |

Annotated functions |

|---|---|---|

|

KU1003-01 |

BBW80_02625 to BBW80_02655 |

Type VI secretion system |

|

KU1003-01 |

BBW80_00155 to BBW80_00225 |

CRISPR system |

|

KU1003-02 |

BBP28_10015 to BBP25_10115 |

Type IV secretion system |

|

RH3002v2f |

BBW69_00525 to BBW69_00530 |

Two-partner putative haemolysin secretion system |

|

RH3002v2g |

BBP27_06840 to BBP27_06885 |

TonB-dependent haem acquisition and utilization |

Virulence genes present in the commensal isolates

Many virulence factors in the pathogenic Neisseria have been identified to date and this has been the focus of a great deal of research due to their importance in public health [6, 84–86]. Within the regions of similarity identified in comparative genome analysis, the presence of a set of 117 virulence genes was assessed in each of the 4 isolates by comparison against the pathogen genome sequences in Mauve. Of the 117 virulence genes investigated, 94 are present in 1 or more of the isolate genome sequences (Table 3). There is some strain-to-strain variation in the presence of homologous sequences, but for some they are present across all of the isolate genomes. For example, there are homologous sequences for the majority of the neisserial type IV pilus genes (Table 3). As has been reported previously [21], it is likely that some of what have been identified as ‘virulence genes’ require reclassification in light of their presence in the non-pathogenic Neisseria spp. genomes and the role for some of these in niche survival, rather than pathogenicity. Virulence genes shared between the commensal and pathogenic species include those involved in host adhesion, invasion, and immune response evasion, with adhesion being critical for successful host colonization [87, 88]. Coding sequences (CDSs) for two efflux pump systems, MtrCDE and FarAB, were identified; these have been investigated in N. gonorrhoeae for their roles in survival against mucosal surface fatty acids and bile salts [89–91].

Possession of type IV pili sequences

Initial binding to host cells, which is important for colonization and microcolony formation, is achieved through the actions of the type IV pili in the pathogenic Neisseria spp. [92]. Commensal Neisseria spp. are also known to be able to produce these structures; electron microscopy confirmed their presence decades ago within N. perflava and N. subflava [93], and the pili of some commensal Neisseria spp. have been demonstrated to have the capacity to adhere to human epithelial cells [94].

The majority of the neisserial pilus genes were identified in all four isolates (Table 3), including those necessary for its biogenesis. Similar to the observations of Marri et al. [12], the pilC sequences identified in the four isolates appear to be orthologues of those found in the pathogens. In the pathogens, PilC is known to be involved in pilus-mediated adhesion as well as pilus biogenesis and is normally present in two copies [95]. A single CDS with homology to pilC was identified in the assembled genomic data for isolates KU1003-01, KU1003-02, and RH3002v2g, while isolate RH3002v2f has two copies. Although the function of the commensal pilC orthologue has not yet been elucidated [12], its presence as an intact CDS within the isolates indicates that these commensals likely have the capacity to produce pili.

All four isolates possess CDSs with homology to the major pilus structural subunit PilE, which associates to form the pilus fibre [96]. In the pathogens, pilE is also responsible for mediating antigenic variation, achieved through recombination with silent pilS pilin sequences [97]. A single copy of pilE was identified in the isolates and a single copy of pilS could be found in the assembled genomic data. In general, the commensals are thought to only have 2–5 copies of pilS, but in the pathogenic Neisseria, up to 19 copies have previously been reported [12].

Pathogen-specific pilus gene sequences were also identified in all four isolates, including pglB, pglC, pglD, pglF, pglG, and pglH. These genes are believed to be necessary for complement-mediated lysis resistance in meningococci through pilin glycosylation [98]. Within the three isolates, RH3002v2f has CDSs for pglB, pglC, pglD, pglF, pglG, and pglH, at one locus. In KU1003-01, KU1003-02, and RH3002v2g, two alleles of pglB were identified (pglB2 and pglB2b). Similar to the observations made by Kahler et al. in N. meningitidis [98], a CDS was found to be inserted between pglB2 and pglC in these three isolates.

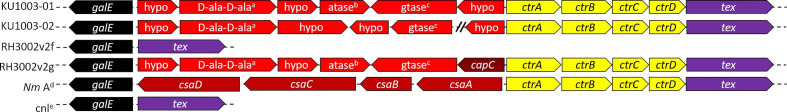

Presence of previously unreported capsule loci sequences

This investigation is the first to identify within the non-pathogenic Neisseria , capsule gene loci sequences that have not previously been characterized (Fig. 3). Analysis of the genome sequence data for KU1003-01, KU1003-02, and RH3002v2g (Table 3) indicates that these isolates contain a number of capsule CDSs homologous to those found in N. meningitidis (Fig. 3). While no capsule CDSs were identified within RH3002v2f, this isolate was found to contain sequences with similarities to those found in N. lactamica strain 020–06 at the syntenic genomic region (Fig. 3) [51, 99].

Fig. 3.

The capsule loci of the four commensal isolates were each different and distinct. For KU1003-01 (line 1), KU1003-02 (line 2) and RH3002v2g (line 4) there are ctr capsule transport genes (yellow) and potentially capsular serogroup defining genes (red) between galE and tex, as in N. meningitidis . An example of a serogroup A meningococcal capsular locus is shown (Nm A line 5). The sequence for KU1003-02 is across two contigs, indicated by \\. RH3002v2f (line 3) does not have ctr or potential capsule biosynthesis genes, rather having a similar locus to the capsule null loci (cnl) found in some meningococci and N. lactamica strain 020–06. a d-ala-d-ala ligase; b acetyltransferase; c glycosyl transferase. d, e are from [100], as is the colour scheme of regions defined previously: D (black); A (red); C (yellow); and E (purple).

The structure of the capsule locus is well characterized and conserved in N. meningitidis [100, 101] and phylogenetic analysis of Neisseria spp. capsule genes carried out by Clemence et al. [7] highlighted that N. subflava was the closest encapsulated relative of N. meningitidis . Putative capsule genes with synthesis, transport, and translocation functions have previously been reported in the non-pathogenic Neisseria spp. [7] and similar to the previous findings for N. subflava, these putative regions were found to be contiguous in isolates KU1003-01 and RH3002v2g and one contig break in the locus occurs in KU1003-02 (Fig. 3).

While the capsule loci of the four commensal isolates were each different and distinct from those in the pathogenic N. meningitidis , capsular synthesis and potential serogroup-defining genes were identified within isolates KU1003-01, KU1003-02, and RH3002v2g (Fig. 3). Similar to the organization of the capsule loci in N. meningitidis serogroup A, the genes involved in capsular synthesis and serogroup definition were identified in isolates KU1003-01, KU1003-02, and RH3002v2g, flanked on both sides by genes involved in capsule transport and capsule translocation.

Homology of capsule loci shared between N. meningitidis and other commensal genomes has indicated that some non-pathogens could represent a reservoir for capsule switching [6, 102, 103]. The acquisition of the capsular genes by N. meningitidis from the non-pathogenic Neisseria spp. evolutionarily [7, 101] and the recent discovery of meningococcal capsule genes in the newly described putatively named Neisseria brasiliensis [103] support the capacity for interspecies transfer of capsular genes between the non-pathogens and N. meningitidis . Although new meningococcal serogroups have not been identified in N. meningitidis, capsule switching could provide a means for circumventing the serogroup specific vaccines directed against it. This would, however, be dependent on the pathogen horizontally acquiring capsular gene sequences from a co-colonizing commensal species in combination with retaining its pathogenicity. Capsule switching in combination with the acquisition of alleles for other vaccine targets, such as sequences for fHbp and NadA (Table 3), that are divergent from the alleles represented in the Bexsero vaccine [104, 105], could provide routes for vaccine escape via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from these commensal genomes. Vaccine targets NHBA and PorA were not found in these isolate genome sequences (Table 3).

The capsule of some N. meningitidis serotypes are considered to be a major pathogenicity factor and its anti-phagocytic properties are essential for growth in the host’s bloodstream [106]. Despite the defined role of the N. meningitidis capsule in virulence, its ecological role is not as well defined, as non-encapsulated N. meningitidis strains are able to grow and survive within the human nasopharynx as well as encapsulated strains, likely better [6, 74, 101]. Further research is needed to determine the role and nature of the potential capsules in the commensal isolates.

Presence of vaccine antigen target sequences that demonstrate diversity in the gene pool of the genus

An adhesin/invasin similar to Neisseria adhesin A (NadA) is present in the genome sequences of isolates KU1003-01 and RH3002v2g, with a yadA homologue in KU1003-02 (Table 3). Submission of these CDSs to Bexsero Antigen Sequence Typing through PUBMLST (https://pubmlst.org/neisseria/NadA/) indicates that the closest match for the protein sequences is N. meningitidis NadA-1, with E values of 2e-08 and 8e-10, respectively. Therefore, although present, the NadA that would be expressed in these N. subflava biovar perflava isolates is predicted to be distinct from those in the Bexsero meningococcal vaccine. In N. meningitidis , nadA assembles at the cell surface and promotes tight adherence followed by invasion of host epithelial cells [107]. Previous investigations into N. lactamica found no CDSs with homology to nadA or Bexsero target fHbp [108], both of which are found in these commensal isolates (Table 3). This analysis demonstrates additional reservoirs for antigenic variant alleles of NadA and Fhbp not represented in the vaccine that may allow N. meningitidis to escape vaccine-mediated control via HGT from commensal Neisseria spp. In concert with the potential role for commensal capsule loci to provide genetic material for capsule switching [6, 101], the scope for evolution of this pathogen, and also for pharyngeal N. gonorrhoeae , through their natural competence preference for the neisserial DNA uptake sequence [78, 81, 82] likely contributes to genome plasticity [109].

Regions of difference within the commensal isolates contain previously explored sequences

Mauve alignments also revealed previously unexplored regions of difference between the four isolate genome sequences. These included both regions that were not present in the other sequenced commensal isolates and regions that were not present in the pathogens and N. lactamica reference strains against which they were compared. Five key regions were identified (Table 4), which were investigated in further detail. Similar to the presence of virulence genes within commensal Neisseria spp., some of these systems are more often associated with pathogens.

Presence of a different Type IV Secretion System

Horizontal exchange of genetic material in N. gonorrhoeae is facilitated through a multicomponent Type IV Secretion System (T4SS), encoded within the Gonococcal Genetic Island (GGI), present in around 80 % of gonococcal strains [27]. This GGI T4SS has also been identified in some N. meningitidis [28], with different capsular serogroup strains containing both complete and partial versions of the GGI [110]. In N. meningitidis , however, this system does not secrete DNA, although its GGI T4SS may be responsible for secreting other effectors [111]. T4SSs in the non-pathogenic Neisseria spp. have not previously been characterized within any of the commensal Neisseria spp. [27].

A T4SS system similar to VirB/D in Agrobacterium tumefaciens (i.e. VirB9 1e-42 at 93 % coverage and VirB11 7e-55 at 90 % coverage) was identified within the genome sequence of isolate KU1003-02 (Table 4). blastp revealed no similarity between the T4SS components found in isolate KU1003-02 and the N. gonorrhoeae GGI T4SS. blastn of the individual VirB/D components could not identify the same system in the other three isolates, or in any N. gonorrhoeae , N. meningitidis , or the vast majority of other Neisseria spp. in the sequence databases. Orthologues were detected in two of the investigated N. subflava biovar perflava genomes [67, 72].

The T4SS in KU1003-02 contains CDSs potentially encoding 11 out of the 12 core proteins (VirB1–VirB11 and VirD4) normally associated with this type of secretion system [112]. The Browse by Replicon function within the SecReT4 database identified organizational synteny between the KU1003-02 T4SS and the VirB/D system in Taylorella equigenitalis [113]. A CDS with homology to virB7 could not be identified within KU1003-02, although a hypothetical protein was predicted at the syntenic location.

Although it is clear that this T4SS has an independent origin from that within the GGI in the pathogenic Neisseria spp., the role of the T4SS in isolate KU1003-02 is currently unclear from the data, and therefore further investigation is required.

Presence of CRISPR systems

Individual species need mechanisms for maintaining their genetic identity [114] and preventing the loss of advantageous genes necessary for their survival and proliferation. CRISPR systems have been proposed as one mechanism by which this is possible and genome size as well as the ability to acquire new genes have been shown to differ between strains that either possess or lack CRISPR systems [115]. CRISPR systems are present in around 40 % of sequenced bacterial genomes, including Neisseria spp. [116], and provide acquired, heritable immunity against the acquisition and genomic incorporation of DNA from invading plasmids and bacteriophages [117]. CRISPR use enzymes to degrade foreign DNA that is either identical or very closely related to previously acquired short DNA sequences [117, 118].

A region of difference was identified in the genome sequence of isolate KU1003-01, annotated as a CRISPR locus (Table 4). To investigate CRISPR sequences in the isolates in more depth, the genome sequences for all four isolates were uploaded to CRISPRminer (http://www.microbiome-bigdata.com/CRISPRminer) [43] and CRISPRfinder (https://crispr.i2bc.paris-saclay.fr/Server/) [44]. Isolate KU1003-01 was found to have three confirmed CRISPR loci with a total of 109 spacers (Table 5) according to CRISPRfinder. CRISPRminer identified at least one of the spacers in isolate KU1003-01 as being complementary to Escherichia phage HY01, with another being identified as self-targeting. The remainder of the spacers for KU1003-01 did not yield any blast hits through the NCBI database. KU1003-02 was found to have two confirmed CRISPR loci with a total of 111 spacers according to CRISPRfinder (Table 5). One spacer was identified as being self-targeting and no phage complement spacers were identified within isolate KU1003-02 according to CRISPRminer. Isolates RH3002v2f and RH3002 v2g were not identified as having CRISPR using these tools, although Cas proteins were identified within their genomic sequences. Lack of bacteriophage hits and inability to identify CRISPR in genome sequences containing Cas protein homologues suggest that these tools may not be able to recognize the diverse nature of the neisserial CRISPR and bacteriophages.

Table 5.

A comparison of genome size and GC content (%) as well as the number of CRISPR loci, spacer number and type across the four isolates

|

Strain/isolate |

Genome size (bp) |

% G+C |

CRISPR loci |

Self-targeting |

Phage spacer |

Spacer no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

KU1003-01 |

2 345 197 |

49.00 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

109 |

|

KU1003-02 |

2 303 261 |

49.40 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

111 |

|

RH3002v2f |

1 953 373 |

50.60 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

RH3002v2g |

2 193 423 |

49.60 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

While CRISPRs are known to provide adaptive immunity through the incorporation of spacers from invading plasmids and bacteriophages, analysis of these systems across a large number of archaea and bacteria genomes also identified CRISPR spacers that were derived from chromosomal DNA [119]. These ‘self-targeting’ spacers are complementary to non-CRISPR genomic regions within the species in which they were found. While it is currently thought that the most likely outcome for cells containing a complementary self-targeting spacer is death through host autoimmune suicide [117, 119], these spacers may also play a role in maintaining host genome integrity [118–120]. It may be that the CRISPR systems identified in isolates KU1003-01 and KU1003-02 have a role in maintaining their genome integrity during co-colonization with other Neisseria spp.

First identification of a Type VI Secretion System in the Neisseria spp

One region of difference found in KU1003-01 included annotated CDSs for a Type VI Secretion System (T6SS) [121, 122], encoding proteins such as EvpB (TssB), Hcp (TssD), ImpG (TssF), VgrG, and PAAR (Table 6). This region was investigated further, identifying a full complement of T6SS sequences across contigs, suggesting that KU1003-01 is able to make a functional T6SS. This is the first report of the potential for Type VI Secretion in this genus.

Table 6.

CDSs with homology to T6SS components present in three of the isolates

|

Name |

KU1003-01 |

KU1003-02 |

RH3002v2g |

T6SS component |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TssA |

BBW80_02650 |

BBP28_06040 |

BBP27_04500 |

Cytosolic protein |

|

TssB/EvpB |

BBW80_01505 |

BBP28_06045 |

BBP27_04505 |

Contractile sheath – small subunit |

|

TssC |

BBW80_01510 |

BBP28_06050 |

BBP27_04510 |

Contractile sheath – large subunit |

|

TssD/Hcp |

BBW80_01485 |

BBP28_06055 |

BBP27_04515 |

Puncturing device inner tube |

|

TssE |

BBW80_02630 |

† |

BBP27_04525 |

T6SS baseplate component |

|

TssF/ImpG |

BBW80_02645 |

BBP28_07375 |

BBP27_04530 |

T6SS baseplate component |

|

TssG |

BBW80_02640 |

BBP28_06155 |

BBP27_04535 |

T6SS baseplate component |

|

TssH/ClpB |

BBW80_01480 |

BBP28_06150 |

BBP27_04540 |

AAA ATPase |

|

TssI/VgrG |

* |

BBP28_06090 |

BBP27_04565 |

Puncturing device tip protein |

|

PAAR |

BBW80_01515 |

BBP28_06085 |

BBP27_04575 |

PAAR domain-containing protein |

|

TssJ |

BBW80_02635 |

np |

BBP27_04545 |

Outer-membrane lipoprotein |

|

TssK |

BBW80_01500 |

BBP28_08095 |

BBP27_04550 |

T6SS baseplate component |

|

TssL |

BBW80_01495 |

np |

BBP27_04555 |

Inner membrane, 1 TM, membrane complex |

|

TssM/IcmF |

BBW80_02655 |

BBP28_06095 |

BBP27_04560 |

Inner membrane, 3 TMs, membrane complex |

*Up to four VgrG with specific effector immunity (EI) pairs are predicted to be within isolate KU1003-01.

†CDS is present across the ends of two contigs.

np, not present.

To expand this discovery to the other isolates, Mauve alignment and nucleotide blastn homology searches were conducted for each of the T6SS components. These revealed that KU1003-02 and RH3002v2g also possess homologues of the T6SS. However, the T6SS in these isolates is different from that seen in KU1003-01. Confirmation of these two different T6SS types was achieved through amino acid sequence alignments using clustal Omega (data not shown). Annotations for T6SS functions were confirmed against the SecRet6 database [46]. No T6SS was identified in isolate RH3002v2f ( N. cinerea ), and therefore the T6SS was only found here in the isolates identified as N. subflava biovar perflava. Analysis of 15 draft and complete N. subflava genome sequences in the NCBI database indicated that the majority of these (8 out of 15) possess T6SSs. The most commonly identified T6SS was the type identified within isolates KU1003-02 and RH3002v2g, with 5 out of 15 genome sequences from the database that were analysed possessing this type and the remaining 3 matching KU1003-01.

The T6SS in isolate KU1003-01 appears to have all of the 13 core components necessary to produce a functioning system [121]. These were identified on putative genomic islands at two different loci with tssE, tssJ, tssG, tssF, tssA, and tssM being identified in one cluster and tssH, tssD, tssL, tssK, tssB, tssC, vgrG, and PAAR at a separate locus. Isolate KU1003-01 is predicted to have up to four vgrG each with different effector–immunity (EI) pairs. The T6SS identified in isolates KU1003-02 and RH3002 v2g, by comparison, were located at a single locus and were predicted to have only one vgrG.

Bioinformatic studies have so far identified the T6SS in around 25 % of Gram-negative bacteria [121] and the products of the genes involved in its assembly are evolutionarily well conserved [122]. It is believed that one function of the T6SS is to aid bacteria in successful colonization and survival within competitive niches and it has been proposed that this system is responsible for shaping the composition of microbial populations [123–125].

It is likely that naturally competent Neisseria spp. colonizing the same niche acquire DNA from one another [12] and the T6SS has been shown to aid this process. T6SS-positive species have been shown to acquire new effector–immunity pairs from their neighbours through this mechanism [126]. In species other than Neisseria , the T6SS has also been shown to play a role in nutrient acquisition [127].

It is possible that the co-isolated KU1003-01 and KU1003-02 have shared T6SS immunity genes, which has allowed them to co-exist together, although further investigation is needed to determine if this is the case. By carrying out further study into the mechanisms of the T6SS, novel therapeutic interventions could be developed with regard to pathogen-related infections. One possible intervention, as suggested by Unterweger et al. [128], would allow non-pathogenic commensal bacteria such as these N. subflava biovar perflava possessing the T6SS to outcompete pathogens such as N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae within a specific niche. The T6SS effector proteins, which are antibacterial to competitor species, have also been proposed to be developed as therapeutic agents against multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens [129].

Similar iron acquisition systems to those of the pathogens, as well as systems not previously seen in Neisseria spp.

In order to establish an infection, pathogenic bacteria must be able to obtain iron from a host and in the case of the pathogenic Neisseria spp. it is considered to be a major virulence determinant [8–11]. It is believed that diversity in iron uptake genes aids colonization of different Neisseria spp. within the same niche where host antibodies are targeted towards a variety of iron acquisition components from different bacterial species [12].

Isolate RH3002v2f was found to contain CDSs homologous to fbpA, fbpB, and fbpC for an ABC-type Fe3+ transport system (FbpABC) and lbpA and lbpB for lactoferrin-binding proteins (Table 3), which were not present in the other isolates. CDSs with homology to hmbR were identified in isolates KU1003-01, KU1003-02, and RH3002v2g for haemoglobin receptor (Table 3). This specificity in differential iron utilization for the N. subflava biovar perflava isolates versus the N. cinerea isolate agrees with earlier results [12].

A two-partner secretion system, not previously identified in Neisseria spp

While none of the isolates were determined to be haemolytic, a two-partner secretion system (TPSS) was identified within isolate RH3002v2f that was predicted to encode a putative haemolysin secretion system (Table 4). This system could not be identified in any of the other isolates. This TPSS is similar to the ShlA/ShlB system of Serratia marcescens [130], which only secretes its haemolysin in low-iron conditions [131], which may explain our observations here. In S. marcescens , shlA encodes a haemolysin and shlB an outer-membrane protein required for the secretion and activation of ShlA [130]. The TPSS identified in isolate RH3002v2f has orthologues in a very small number of other commensal neisserial genomes, including N. cinerea [53]. Many pathogens, including N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae , are known to possess a wide range of mechanisms for iron acquisition [11] and are able to utilize haem released by haemolysis as an iron source. Heme constitutes the largest source of iron within a human host [132] and while there is normally a limited supply within the nasopharynx, meningococci are thought to be able to take up small amounts through the expression of TonB-dependent receptors [133].

A heme system, not previously identified in Neisseria spp.

An operon containing a TonB-dependent haem acquisition and utilization system was identified within the genome for isolate RH3002v2g, similar to the hutWXZ system in Vibrio cholerae [134]. The same system was also identified in the genome sequence data for isolate KU1003-01, as well as in the 15 N. subflava spp. investigated and in a number of N. perflava , N. flavescens , N. elongata, and N. lactamica genomes. Within N. subflava , the genes surrounding the TonB-dependent haem acquisition and utilization system fell into two groups, consistent with the type of T6SS they possessed.

In the first group, the TonB-dependent haem acquisition and utilization system was identified next to CDSs encoding a T6SS VgrG protein with a predicted anti-eukaryotic effector. T6SS effects have previously been shown to be involved in metal acquisition [135] in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and iron acquisition in P. aeruginosa [125]. It is possible that under conditions of iron starvation, the T6SS and TonB-dependent haem acquisition and utilization systems act together for the purpose of iron acquisition in some of the commensal Neisseria spp. In the second group, which consisted of the second neisserial T6SS type, as well as all T6SS-negative N. subflava , the haem acquisition and utilization system is associated with a zonula occludens toxin-like protein (Zot) homologue; Zot disrupts mucosal tight junctions in V. cholerae and orthologues have been found in N. meningitidis and Campylobacter concisus [136, 137].

Conclusions

In-depth investigations of the genome sequences of non-pathogenic Neisseria spp. are of interest in their own right, revealing themselves to not only be reservoirs of a large gene pool for the naturally competent genus, but also to contain genetic features not previously seen, such as the first reported Neisseria T6SS. A wealth of new biological insight into this genus can be gained by further investigating the functions of the previously unexplored features described here in this N. cinerea and its TPSS and three N. subflava biovar perflava and their T6SSs. In addition to the potential of the antibacterial activity of the T6SS expressed by these isolates, the individual T6SS effectors identified in these genome sequences might also be promising avenues for development of antibacterials against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Funding information

This work was part-funded by a Swan Alliance project grant awarded to L. A. S. S.

Acknowledgements

M. A., A. I., H. A. S. M., A. M., and L. T. were not available to confirm coauthorship, but the corresponding author L. A. S. S. affirms that the authors M. A., A. I., H. A. S. M., A. M., and L. T. contributed to the paper and vouches for M. A., A. I., H. A. S. M., A. M., and L. T.'s coauthor status. This publication made use of the Neisseria Multi Locus Sequence Typing website (https://pubmlst.org/neisseria/NadA/) sited at the University of Oxford. The development of this site has been funded by the Wellcome Trust and European Union.

Author contributions

A. C., C. J. M.: investigation; writing – review and editing. A. Ç., J. L. S., R. S., E. S.: investigation; data curation. A. W., A. H. K., E. B., K. Y., N. S., B. A., M. A., A. I., T. K., A. L., H. A. S. M., A. M., L. T.: investigation. A. J. S.: project administration. L. A. S. S.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing – original draft, review and editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

Ethical statement

Ethical approval for the collection of bacterial samples from human volunteers was granted by the Kingston University Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all volunteers.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: DUS, DNA uptake sequences; DUSvar1, DUS variant 1; DUSvar2, DUS variant 2; EI, effector immunity; GGI, Gonococcal Genetic Island; HGT, horizontal gene transfer; LOS, lipooligosaccharide; MCM, Mauve contig mover; rMLST, ribosomal multi locus sequence typing; TPSS, two-partner secretion system; T4SS, Type IV Secretion System; T6SS, Type VI Secretion System; XDR, extensively drug resistant.

All supporting data, code and protocols have been provided within the article or through supplementary data files.

References

- 1.Gao Z, Kang Y, Yu J, Ren L. Human pharyngeal microbiome may play a protective role in respiratory tract infections. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2014;12:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verma D, Garg PK, Dubey AK. Insights into the human oral microbiome. Arch Microbiol. 2018;200:525–540. doi: 10.1007/s00203-018-1505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu G, Tang CM, Exley RM. Non-pathogenic Neisseria: members of an abundant, multi-habitat, diverse genus. Microbiology. 2015;161:1297–1312. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. Genbank. nucleic acids Res. 2009;37:D26–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson AP. The pathogenic potential of commensal species of Neisseria . J Clin Pathol. 1983;36:213–223. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rouphael NG, Stephens DS. Neisseria meningitidis: biology, microbiology, and epidemiology. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;799:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-346-2_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemence MEA, Maiden MCJ, Harrison OB. Characterization of capsule genes in non-pathogenic Neisseria species. Microb Genom. 2018;4 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducey TF, Carson MB, Orvis J, Stintzi AP, Dyer DW. Identification of the iron-responsive genes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae by microarray analysis in defined medium. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4865–4874. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4865-4874.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohde KH, Dyer DW. Mechanisms of iron acquisition by the human pathogens Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae . Front Biosci. 2003;8:d1186–1218. doi: 10.2741/1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caza M, Kronstad JW. Shared and distinct mechanisms of iron acquisition by bacterial and fungal pathogens of humans. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:80. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parrow NL, Fleming RE, Minnick MF. Sequestration and scavenging of iron in infection. Infect Immun. 2013;81:3503–3514. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00602-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marri PR, Paniscus M, Weyand NJ, Rendón MA, Calton CM, et al. Genome sequencing reveals widespread virulence gene exchange among human Neisseria species. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coureuil M, Join-Lambert O, Lécuyer H, Bourdoulous S, Marullo S, et al. Mechanism of meningeal invasion by Neisseria meningitidis . Virulence. 2012;3:164–172. doi: 10.4161/viru.18639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell L, Coley K, Morgan J. An unexpected increase in Neisseria meningitidis genital isolates among sexual health clinic attendees, Hamilton, New Zealand. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:469–471. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181659248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Retchless AC, Kretz CB, Chang HY, Bazan JA, Abrams AJ, et al. Expansion of a urethritis-associated Neisseria meningitidis clade in the United States with concurrent acquisition of N. gonorrhoeae alleles. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:176. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4560-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris SR, Klausner JD, Buchbinder SP, Wheeler SL, Koblin B, et al. Prevalence and incidence of pharyngeal gonorrhea in a longitudinal sample of men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1284–1289. doi: 10.1086/508460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hananta IPY, De Vries HJC, van Dam AP, van Rooijen MS, Soebono H, et al. Persistence after treatment of pharyngeal gonococcal infections in patients of the STI clinic, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2012-2015: a retrospective cohort study. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93:467–471. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eyre DW, Sanderson ND, Lord E, Regisford-Reimmer N, Chau K, et al. Gonorrhoea treatment failure caused by a Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with combined ceftriaxone and high-level azithromycin resistance, England, February 2018. Euro Surveill. 2018 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.27.1800323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eyre DW, Town K, Street T, Barker L, Sanderson N, et al. Detection in the United Kingdom of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae FC428 clone, with ceftriaxone resistance and intermediate resistance to azithromycin, October to December 2018. Euro Surveill. 2019 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.10.1900147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Facius D, Fussenegger M, Meyer TF. Sequential action of factors involved in natural competence for transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae . FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;137:159–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snyder LA, Saunders NJ. The majority of genes in the pathogenic Neisseria species are present in non-pathogenic Neisseria lactamica, including those designated as 'virulence genes'. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett JS, Bratcher HB, Brehony C, Harrison OB, Maiden MCJ. The Genus Neisseria. In: Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F, . The Prokaryotes: Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria. 2014. pp. 881–900. In. editors. pp. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maiden MC. Population genomics: diversity and virulence in the Neisseria . Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:467–471. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maiden MC, Harrison OB. Population and functional genomics of Neisseria revealed with gene-by-gene approaches. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1949–1955. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00301-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higashi DL, Biais N, Weyand NJ, Agellon A, Sisko JL, et al. elongata produces type IV pili that mediate interspecies gene transfer with N. gonorrhoeae . PLoS One. 2011;6:e21373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett JS, Jolley KA, Earle SG, Corton C, Bentley SD, et al. A genomic approach to bacterial taxonomy: an examination and proposed reclassification of species within the genus Neisseria . Microbiology. 2012;158:1570–1580. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.056077-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillard JP, Seifert HS. A variable genetic island specific for Neisseria gonorrhoeae is involved in providing DNA for natural transformation and is found more often in disseminated infection isolates. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:263–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsey ME, Woodhams KL, Dillard JP. The Gonococcal Genetic Island and Type IV Secretion in the Pathogenic Neisseria . Front Microbiol. 2011;2:61. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kellogg DS, Peacock WL, Deacon WE, Brown L, Pirkle DI. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. virulence genetically linked to clonal variation. J Bacteriol. 1963;85:1274–1279. doi: 10.1128/JB.85.6.1274-1279.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]