Abstract

Purpose

Participation in cancer support groups can provide a sense of community and may better prepare patients for interactions with their health care team. Online interactions may overcome some barriers to in-person support group participation. #BCSM (breast cancer social media), the first cancer support community established on Twitter, was founded in 2011 by two breast cancer survivors. The aims of this study are to describe the growth and changes in this community and to discuss future directions and lessons that may apply to other online support communities.

Methods

Symplur Signals was used to obtain all #BCSM Twitter data from January 1, 2011, to January 1, 2020 (00:00:00 Coordinated Universal Time for both). Hashtag use by selected stakeholder groups, user locations, weekly tweet chat activity, and topics were determined.

Results

From year 1 (2011) to year 9 (2019), tweets using the #BCSM hashtag increased by 424%. Tweets by patient advocates increased by 226%, with a peak in 2016. Impressions, a measure of potential tweet views, by patient advocates increased by 517%. Tweets by doctors and nonphysician health care professionals increased by 693%. Weekly #BCSM tweet chat activity peaked in 2013, increasing by 58.1% from 2011. Chat topics have included survivorship, metastatic breast cancer, death and dying, advocacy, and highlights from national breast cancer meetings.

Conclusions

#BCSM has experienced tremendous growth since 2011, although there are challenges to community sustainability. The weekly chats, as well as discussions utilizing the hashtag but occurring outside of scheduled chat times, serve as an important resource for patients and offer physicians an opportunity to both support and learn from patients.

Keywords: social media, breast cancer, support group, #BCSM, Twitter, patient advocacy

Recognizing the importance of psychosocial support for patients with cancer, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers call for support groups and services as part of their accreditation standards for survivorship care.1,2 Participation in cancer support groups can provide reassurance and a sense of community and may better prepare patients for interactions with their health care team.3,4 The benefits of participation have been shown to persist even after active treatment.5 However, there are challenges to in-person support for both sponsoring organizations and patients. These include costs of securing a meeting space and facilitator, inconvenient meeting times, direct and indirect costs to attend (transportation, time off of work, arranging for childcare, etc), variable compatibility for patients who attend an in-person group, and discomfort sharing personal information in a face-to-face setting.3,6,7

The use of online support may lessen or eliminate some of the challenges to in-person support group participation. A growing number of adults in the United States use some form of social media regularly, and more than half of U.S. adult internet users have searched online for health information.8 A recent survey of 1280 patients with cancer found that 20% of those with internet access read about other people’s health experiences, more than one-third wrote about their personal experiences, and 12% participated in online support groups.9 A large number of online forums are used by people with cancer,4,10,11 and those with a history of breast cancer are more likely than those with other cancers to use online communities.3,6,7 Online support may provide additional benefits, including immediate or on-demand interactions and a sense of anonymity.3–7,10,12

#BCSM (breast cancer social media) was the first Twitter community created to provide education and support for patients with cancer. The first tweet chat occurred on July 4, 2011, and discussed the topic “What’s normal now?” Since then, the #BCSM hashtag has been used not only during weekly scheduled chats but at all times of the day or night to tag information, requests for support, or other content relevant to anyone impacted by breast cancer.

The aim of this study is to describe the growth and changes in the #BCSM community from 2011 to 2019. In addition, we discuss lessons learned and future directions for #BCSM and other online patient communities.

METHODS

We obtained an institutional review board waiver for this study from Lowell General Hospital (Lowell, MA) based on the public nature of content published online. The #BCSM cofounders registered the hashtag on July 4, 2011, with Symplur (https://www.symplur.com), a health care-focused Twitter database and analytics program. Health care hashtag registration, a free process, is necessary for Symplur to track hashtag use and provide analytics. We evaluated all tweets containing the #BCSM hashtag from January 1, 2011 (00:00:00 Coordinated Universal Time), to January 1, 2020 (00:00:00), utilizing Symplur Signals. This subscription platform uses natural language software and a proprietary algorithm to categorize Twitter accounts (both individual and organization accounts) into different health care stakeholder categories13 so that patterns and trends in hashtag use may be better defined. We included all stakeholder categories except accounts identified by Symplur as spam.

To describe the overall cohort from 2011 to 2019, we evaluated #BCSM hashtag use by all participants and by the following stakeholder groups: patient advocates (defined as either patients or advocates based on Twitter profile); doctors; nonphysician health care professionals (HCPs); caregivers; government organizations; academic or research organizations; advocacy organizations; media organizations; and pharmaceutical industry companies. We combined doctors and nonphysician HCPs to calculate the overall growth of all medical providers utilizing the hashtag, not just physicians. We analyzed longitudinal use calibrated to Coordinated Universal Time. We collected data on the number of participants, number of tweets, and impressions. Impressions, defined by the software as an estimate of the potential reach of each tweet, are calculated by multiplying an account’s follower count by each tweet when posted (eg, one tweet by someone with 1000 followers yields 1000 impressions). To provide some comparison, we evaluated overall growth in Twitter use during the same time period using public data on the website Statistica.com. We evaluated participants’ locations both by country and by U.S. state, as defined by the software, by interpreting only public Twitter profile data. To ascertain what content was most frequently shared, we extracted the 100 most common words used in tweets. We did not analyze the content of individual tweets or evaluate tweet responses in this study.

Weekly Monday tweet chat activity (21:00–22:00 Eastern Standard Time, accounting for daylight savings time when appropriate) was determined. We categorized the topic of each chat by downloading transcripts and reviewing records of the two moderators (A.C.S. and D.J.A.). Beyond identifying the main theme, we did not perform a detailed content analysis of the individual chats.

We initially collected data for 2011–2018 in November 2019. To include 2019, we conducted the same process of data extraction in January 2020. We calculated endpoints with Microsoft Excel for Mac 2019 (Version 16.32, Microsoft Corporation).

RESULTS

Use of #BCSM, 2011–2019

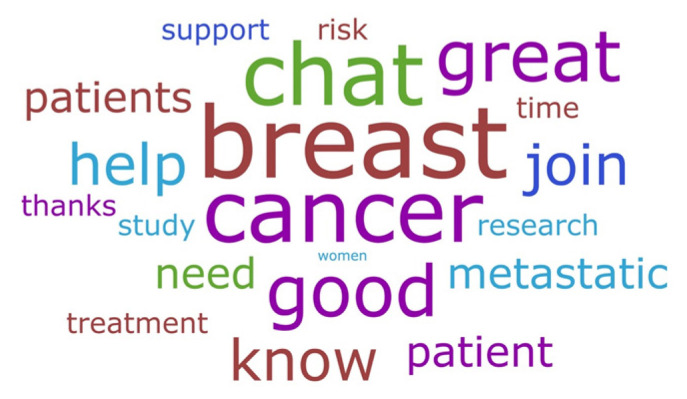

Table 1 shows the summary of #BCSM hashtag use from 2011 to 2019. User engagement and location of hashtag users is shown in Table 2. A total of 75,685 of accounts shared 830,925 tweets with the #BCSM hashtag for an average of 11.2 tweets per hour during the entire study period. Of those tweets, 53.1% were unique rather than retweets, and 9.0% received replies; 888 users (1.2%) each had >100 tweets with #BCSM. The number of impressions, a measure of estimated potential reach of #BCSM-inclusive tweets, was 4.22 billion. Among users with known location by country, most were from the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada. For the 7007 users self-reporting the United States as their country, the 5 most common states were California (12.4%), New York (10%), Texas (8.3%), Massachusetts (5.2%), and Florida (4.5%). The 20 most frequently used words included cancer, research, and support (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary of #BCSM Hashtag Use, 2011–2019

| Metric | n |

|---|---|

| Users | 75,685 |

| Tweets | 830,925 |

| Unique tweets | 441,313 |

| Tweets with replies | 74,575 |

| Impressions | 4,222,228,512 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Twitter Accounts Participating in the Hashtag #BCSM

| User engagement | No. of participants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Number of tweets | ||

| 1–10 | 70,320 | 92.9% |

| 11–25 | 2647 | 3.5% |

| 26–50 | 1123 | 1.5% |

| 51–100 | 707 | 0.9% |

| 101–250 | 469 | 0.6% |

| >250 | 419 | 0.6% |

| Location by country | ||

| United States (U.S.) | 7007 | 9.3% |

| United Kingdom | 1982 | 2.6% |

| Canada | 549 | 0.7% |

| Spain | 383 | 0.5% |

| Other | 3137 | 4.1% |

| Unknown | 62,627 | 82.7% |

| Location in U.S. by state | ||

| California | 867 | 12.4% |

| New York | 704 | 10.0% |

| Texas | 580 | 8.3% |

| Massachusetts | 361 | 5.2% |

| Florida | 318 | 4.5% |

| Pennsylvania | 308 | 4.4% |

| Illinois | 258 | 3.7% |

| Washington, DC | 248 | 3.5% |

| Ohio | 242 | 3.4% |

| North Carolina | 224 | 3.2% |

| Other known | 2465 | 35.2% |

| Unknown | 432 | 6.2% |

Figure 1.

Top 20 #BCSM-associated words. (Created with www.wordclouds.com on March 1, 2020.)

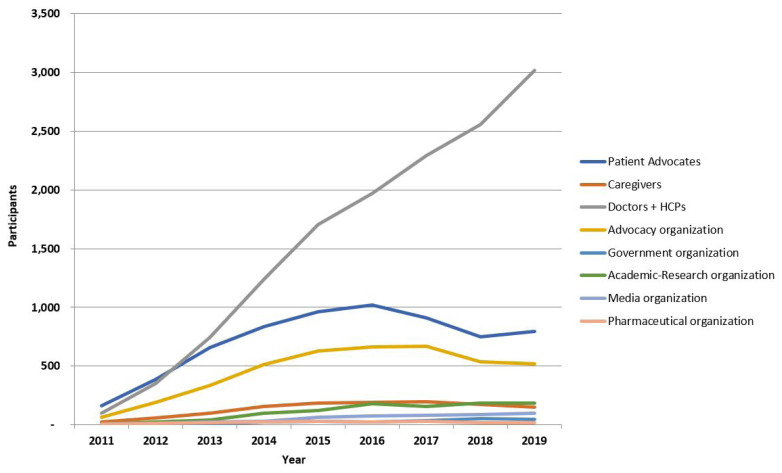

Hashtag Use by All Participants and Specific Stakeholders

The annual number of Twitter accounts posting with #BCSM increased from 602 in 2011 to 19,841 in 2019, a 3196% increase (Figure 2). Accounts identified as belonging to patient advocates increased from 163 to a high of 1018 in 2016 but then decreased to 794 in 2019 (a 387% overall increase from 2011 to 2019). Doctor/HCP accounts increased from 96 in 2011 to 3016 in 2019, a 3042% increase. Caregiver use peaked at 197 accounts in 2017. Use by government, academic-research, and media organizations increased during the period studied, whereas use by advocacy and pharmaceutical organizations declined from their 2017 peaks. We were not able to obtain total number of tweets (all Twitter activity) from 2011 to 2019, but the number of active monthly users on Twitter rose from 10 million in Quarter 3 of 2011 to 330 million in Quarter 1 of 2019, a 227% increase.14

Figure 2.

#BCSM participants by stakeholder group.

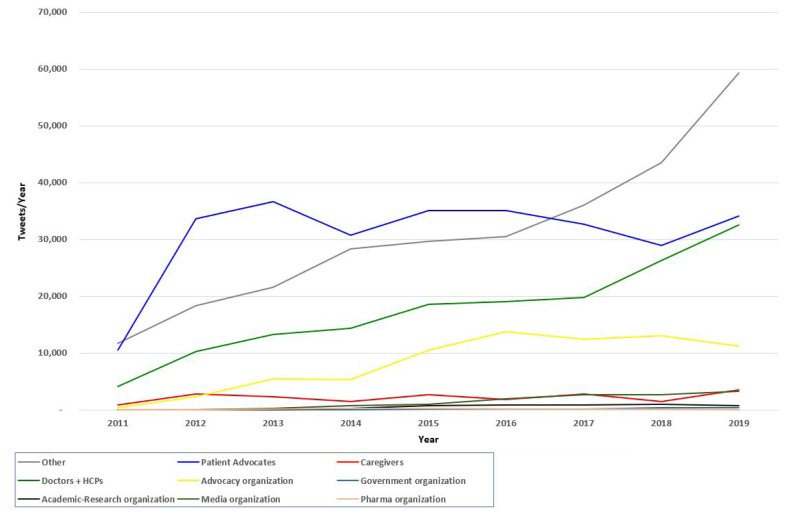

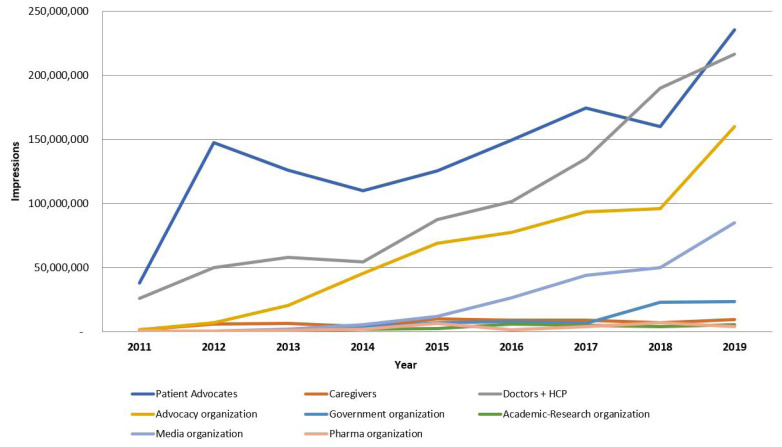

Tweets and Impressions by Stakeholder

The numbers of tweets by selected stakeholders are shown in Figure 3. The total number of tweets per year using the #BCSM hashtag increased from 27,781 in 2011 (reflecting use from July 4, 2011, to December 31, 2011) to 145,619 in 2019, a 424% increase. Tweets by patient advocates increased by 226% (34,199 in 2019 vs 10,492 in 2011), with a peak in 2016; tweets by doctors and HCPs increased by 693% (32,574 vs 4107) with no decline to date. #BCSM impressions (a user’s number of tweets using the #BCSM hashtag multiplied by their number of followers) per year by selected stakeholder are shown in Figure 4. The number of #BCSM impressions by patient advocates increased by 517% without a decline. Total impressions by patient advocates are higher than impressions by doctors/HCPs.

Figure 3.

#BCSM tweets by stakeholder group.

Figure 4.

#BCSM impressions by stakeholder group.

Weekly Chat Activity and Topics

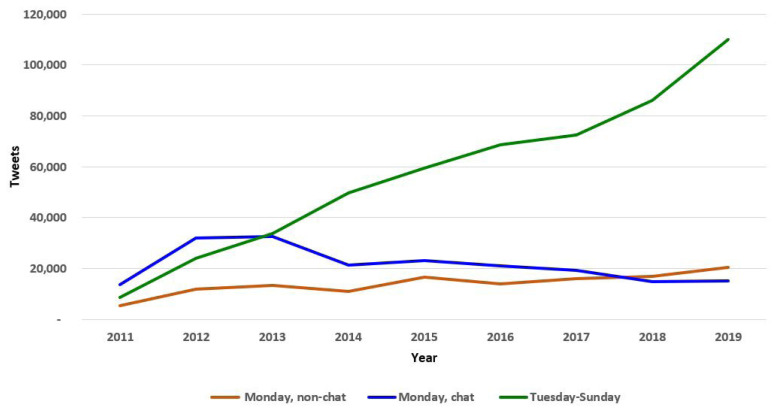

#BCSM hashtag use during weekly Monday chats as well as non-chat Monday use is shown in Figure 5. Monday tweet chat activity peaked in 2013, increasing by 58.1% from 2011 to 2013. Non-chat Monday activity and total annual activity (minus Monday and chat) have both increased over time. Weekly chats have covered survivorship concerns, metastatic breast cancer, death and dying, advocacy, and highlights from national breast cancer meetings. Representative chat topics are shown in Table 3.

Figure 5.

#BCSM activity, chat vs non-chat.

Table 3.

Selected #BCSM Chat Topics

| Survivorship |

| What’s normal now (inaugural chat) |

| Isolation of cancer, posttreatment depression, anxiety, grief, facing fears |

| Work/life balance, cancer and careers, working through cancer |

| Impact on family/parenting/relationships/dating |

| Posttreatment depression, survivor’s guilt, stages of healing, cancer anger, rebuilding self-confidence |

| Financial toxicity |

| Faith and cancer |

| Surviving the holidays with cancer |

| Creative coping, invisible scars |

| Community – virtual and in real life |

| Breast cancer disparities |

| Caregiving, support for the caregiver |

| Open mic night |

| Advocacy |

| Pinktober, Telling your story |

| Volunteering, cancer advocacy, the advocate’s perspective, one person can make a difference |

| Moving awareness to action |

| Metastatic breast cancer |

| #FearlessFriends |

| More for #MetsMonday |

| Metastatic breast cancer project |

| Death and dying |

| In memory of/Honoring (various) |

| Learning to live with loss |

| Celebrate the lives of those no longer with us |

| Medical and health care |

| No evidence of disease and cancer free, cancer screening, overdiagnosis/overtreatment |

| Surgery, medical oncology, radiation oncology topics, “ask the docs” |

| Inflammatory breast cancer, male breast cancer, global burden of breast cancer, lobular breast cancer |

| Young women and breast cancer, racial/ethnic disparities |

| Palliative care, clinical trials, chemobrain |

| Sexual wellness after cancer, lymphedema, PTSD, genetic testing, nutrition and weight management |

| What is a tumor board, open notes |

| Myths and misconceptions, separating fact from fiction |

| Reimagining health care, communicating with your medical team, shared decision-making |

| Medical meetings |

| Highlights from AACR, ASBrS, ASCO, SABCS, SSO |

AACR, American Association for Cancer Research; ASBrS, American Society of Breast Surgeons; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SABCS, San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; SSO, Society of Surgical Oncology.

DISCUSSION

The robust use of the #BCSM hashtag during and outside scheduled chat hours speaks to the value for patients, physicians, and other interested stakeholders in having breast cancer-related content organized around a designated cancer-specific tag.15,16 The #BCSM hashtag has come to not only represent a weekly virtual meeting space for all who are affected by breast cancer, but it also serves as an online filter or tag for breast cancer-related information for all who are interested. Some of the success of #BCSM, as the first online community of its kind on Twitter, is likely related to its filling a need for patients seeking information and support on this platform.

Common concerns expressed regarding virtual support groups, as well as any online health information site, include the quality of information shared, that participation may deter patients from seeking advice from a medical professional, the potential for information overload, and privacy concerns.12 However, these concerns also exist, with the exception of digital privacy, in face-to-face groups.

Quality of Information

The #BCSM cofounders made clear that they intended to focus on evidence-based content, and in response to a 2015 survey of the community, 80% of respondents noted that chat participation improved their knowledge regarding various aspects of breast cancer treatment.6 Others have found that participation in online forums may empower patients to become more involved in their care,12,17 and patients with breast cancer who participated in online forums were found to have higher satisfaction with treatment recommendations.18

Emotional Support

The #BCSM chats often serve as forums for frank, unfiltered discussions on living with breast cancer, including survivorship issues, metastatic breast cancer, and death. In fact, a pivotal moment in defining the impact and importance of the community was when two participants with metastatic breast cancer died on the same Monday (February 6, 2012). The chat that evening, which focused on their memory and legacy, allowed the people who had come to know and love them to gather to express their grief and support one another. The memorial and grieving process continued through the following week’s chat (titled “Learning to live with loss,” February 13, 2012). The responses of regular and even occasional participants to the events during those 2 weeks reinforced that relationships formed in online communities are in fact very real.

While participation in #BCSM chats has been associated with a decrease in anxiety levels,6 a reality of any cancer-related support group is exposure to others’ disease progression and death. This psychologic amplification of “shared suffering” online may negatively affect participants while strengthening bonds for others.10,16,19 More research is needed on how to best support patients who experience grief and loss in the virtual space.

Community Sustainability

Challenges to sustaining an online support community include participant turnover, ensuring diversity, increasing “noise” as the platform becomes more popular, digital privacy, and leader burnout.16 Many original participants no longer actively discuss their breast cancer on Twitter, and some no longer have a presence on the platform at all. Everyone’s need for support is different, and as in face-to-face support groups, patients may rotate out after their need has been served. Patients facing a new early-stage diagnosis have different needs and priorities versus those with advanced-stage or metastatic breast cancer. It is challenging to provide support to all, especially as personalized approaches to treatment become more common. Since 2011, multiple online breast cancer information and support forums have developed, and patients may increasingly be seeking support groups that target their own situation as specifically as possible.

The most active participants in online cancer communities are more likely to be white, well-educated, and of higher socioeconomic background than those who are passive participants or who do not utilize online support.20 Early efforts were made to discuss racial inequalities in breast cancer treatment and outcomes, but the pace of developing a racially and ethnically diverse community has been slow. Several individuals and organizations currently participating in the #BCSM chats provide a much-needed perspective on the experience of patients in racial and ethnic minority groups. However, large segments of the population, including older adults, patients with lower education or socioeconomic status, and those with low digital literacy, are likely not being served by online support communities.10,21 It is important for people involved in developing digital information and support tools to ensure that these patients are not left out.

An increasing number of physicians and nonphysician HCPs are using the #BCSM hashtag, and they have contributed to tweet chat discussions on treatment standards of care, highlights from national breast cancer meetings, and the importance of clinical trials. Physician engagement in online patient communities has the potential to improve the quality of information shared.9,11 While physician presence has increased, the number of patient advocates who utilize the #BCSM hashtag has declined. However, we found an increase in impressions by patient advocates. Therefore, while the number of patient advocates using #BCSM is decreasing, those who continue to participate have an increasing number of followers and potential influence. However, as #BCSM hashtag use has increased by those who are not patients, it may become harder for patients to connect with one another outside a designated chat. For patients solely interested in peer support, the use of the hashtag by nonpatients may be seen as Twitter “noise.” One potential solution is for patients to use a second hashtag to accompany #BCSM, which could further filter out noise and direct their tweets to a smaller group of people. This practice could pass by word of mouth, but Twitter’s lack of permanent content makes it hard to set up “community guidelines” for new or current participants. Another option would be for patients to leave Twitter and migrate to other platforms, such as closed Facebook groups, which may be better able to focus content and control participants.

Maintaining a robust patient presence in this open space is not only important for peer support but also to help educate physicians and researchers about the issues faced by patients and to inform ideas for research and advocacy. Some 72% of respondents to a 2015 survey planned to increase outreach and advocacy efforts as a result of participation in #BCSM tweet chats.6 These men and women are ready, willing, and able to help develop and support research projects that address their needs and concerns. The Metastatic Breast Cancer Project is an example of the successful use of the online community as a research partner. In 2015, their research team partnered with the #BCSM community to disseminate information about the project. Patients throughout the United States then participated by sending in medical records, pathology slides, and saliva samples for analysis.22

Patients’ reliance, as their sole source of support, on platforms that constantly change their privacy and policy settings raises concerns. Recently, some Facebook patient communities have experienced well-publicized privacy violations, and some patient groups have been dropped by the platform.23 While many of the cancer-specific Twitter communities have websites where “evergreen content” and chat transcripts could be stored for those new to the community or not active on Twitter, these sites do not provide real-time support, a key benefit for #BCSM participants and other online support communities.7,24

The co-moderators of #BCSM (A.C.S. and D.J.A.) and moderators of the other online patient communities serve as volunteer leaders. One of the #BCSM cofounders died in 2016, and the remaining cofounder (A.C.S.) serves as a constant point of contact for those with questions or concerns, well outside the bounds of weekly chat times. Burnout can affect anyone working long hours in an oncology space, even when it is a “labor of love.” Identifying other patient advocates willing to co-lead on a consistent basis has been challenging but is an area that needs attention. This effort can help to improve the diversity in the community while maintaining a patient-centered focus and also may help to limit stagnation and leader burnout. Steps to ensure that the community continues to serve the needs of its core stakeholders could include surveys as well as an open-door policy on accepting comments and suggestions for topics and guests. Whether or not the concept of a community open to all, regardless of disease stage or other characteristics, is sustainable in this era of personalized medicine remains to be seen.

Limitations

There are some limitations to our data. Our aim was to provide an overview of the use of #BCSM, and we utilized Symplur Signals to track hashtag activity. However, the software’s stakeholder characterization is not a straightforward process, relying on a combination of self-reported (Twitter biography) information as well as natural language processing. In early 2019, the company changed the classification of “patient” to “patient advocate,” so we could not distinguish between breast cancer patients and people considered advocates by examining large tweet volumes over the course of 8.5 years. The current classification of advocacy organizations includes nonprofits such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Cancer Society, even though these organizations have very different stakeholders and missions. Individuals and organizations may be listed in more than one stakeholder category. A large number of stakeholders are characterized as “unknown” (11,735 users in 2019), and we did not attempt to further characterize these accounts. Those who use the software to analyze health care-related content and communities should be aware of these limitations.

It is possible that the increased use of the #BCSM hashtag may in part reflect the increased popularity of Twitter as a forum for information exchange, not specifically due to patient desire for community support. However, we observed a much larger growth rate in accounts using the #BCSM hashtag compared with general Twitter use. We did not perform a formal content analysis to ensure every post was breast cancer-related, but we observed no signs in our study that there are other uses for this hashtag with a separate meaning online. That is, in part, why this nonintuitive hashtag has worked well to engage many people.

Additionally, our information only reflects those who have used the #BCSM hashtag in at least one tweet; it is not possible to determine how many individuals monitor the hashtag but do not use it in their own posts. We examined volume of tweet activity and did not analyze reply threads. Therefore, we may be underestimating the number of people who read content using the hashtag or who reply to #BCSM-related tweets but do not include the hashtag. Future work involving health care hashtags should include content and conversation analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

The #BCSM online community has experienced tremendous growth since 2011, though there are challenges to its continued sustainability. All of the current cancer-focused tweet chats were founded and are moderated by patients. These chats, and the discussions utilizing the hashtag but occurring outside of scheduled chat times, may serve as a potential opportunity for physicians to support patients by adding high-quality information to the online space. More research is necessary to define the best ways to serve patients’ needs within these online communities.

Patient-Friendly Recap.

Breast cancer support groups can provide a sense of community for patients. Online interactions may overcome barriers to in-person support group participation.

The authors reviewed Twitter data for the online community #BCSM (breast cancer social media), a hashtag founded in 2011 by two breast cancer survivors.

They found that use of the #BCSM hashtag grew drastically from 2011 to 2019, particularly among patient advocates, physicians, and other health care professionals.

Recent dips in some data metrics indicate online resources like #BCSM must continually adapt to meet the evolving needs of new patients and remain impactful.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated in loving memory to Jody Schoger.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Study design: all authors. Data acquisition or analysis: all authors. Manuscript drafting: all authors. Critical revision: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Katz has stock ownership in U.S. Physical Therapy, Inc., Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd, Mazor Robotics Ltd., Healthcare Services Group, Inc. There are no other author conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Commission on Cancer. Optimal Resources for Cancer Care: 2020 Standards. [accessed March 1, 2020]. Effective January 2020. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/cancer/coc/optimal_resources_for_cancer_care_2020_standards.ashx.

- 2.National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers; American College of Surgeons. National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers Standards Manual, 2018 Edition. [Accessed March 1, 2020]. https://accreditation.facs.org/accreditationdocuments/NAPBC/Portal%20Resources/2018NAPBCStandardsManual.pdf.

- 3.Bender JL, Jimenez-Marroquin MC, Ferris LE, Katz J, Jadad AR. Online communities for breast cancer survivors: a review and analysis of their characteristics and level of use. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1253–63. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1655-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huber J, Muck T, Maatz P, et al. Face-to-face vs. online peer support groups for prostate cancer: a cross-sectional comparison study. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikal JP, Beckstrand MJ, Parks E, et al. Online social support among breast cancer patients: longitudinal changes to Facebook use following breast cancer diagnosis and transition off therapy. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14:322–30. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00847-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attai DJ, Cowher MS, Al-Hamadani M, Schoger JM, Staley AC, Landercasper J. Twitter social media is an effective tool for breast cancer patient education and support: patient-reported outcomes by survey. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(7):e188. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bender JL, Katz J, Ferris LE, Jadad AR. What is the role of online support from the perspective of facilitators of face-to-face support groups? A multi-method study of the use of breast cancer online communities. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:472–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sedrak MS, Salgia MM, Decat Bergerot C, et al. Examining public communication about kidney cancer on Twitter. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2019;3:1–6. doi: 10.1200/CCI.18.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An LC, Wallner L, Kirch MA. Online social engagement by cancer patients: a clinic-based patient survey. JMIR Cancer. 2016;2(2):e10. doi: 10.2196/cancer.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harkin LJ, Beaver K, Dey P, Choong K. Navigating cancer using online communities: a grounded theory of survivor and family experiences. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:658–69. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0616-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platt JR, Brady RR. #BCSM and #breastcancer: contemporary cancer-specific online social media communities. Breast J. 2020;26:729–33. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falisi AL, Wiseman KP, Gaysynsky A, Scheideler JK, Ramin DA, Chou WS. Social media for breast cancer survivors: a literature review. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:808–21. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Healthcare stakeholder classifications for Symplur Signals. [Accessed May 5, 2020]. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1Ap6B2-3YCCmy-SWJHLORj-ns75xBomsVGKL002H9ZO0/edit#gid=0.

- 14.Statista. Number of monthly active Twitter users worldwide from 1st quarter 2010 to 1st quarter 2019. [accessed May 3, 2020]. Released April 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/282087/number-of-monthly-active-twitter-users/

- 15.Katz MS, Utengen A, Anderson PF, et al. Disease-specific hashtags for online communication about cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:392–4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz MS, Anderson PF, Thompson MA, et al. Organizing online health content: developing hashtag collections for healthier internet-based people and communities. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2019;3:1–10. doi: 10.1200/CCI.18.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan SS, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(1):e9. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallner LP, Martinez KA, Li Y, et al. Use of online communication by patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer during the treatment decision process. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1654–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bisceglio P. How social media is changing the way we approach death. The Atlantic. [accessed March 1, 2020]. Published August 20, 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/08/how-social-media-is-changing-the-way-we-approach-death/278836/

- 20.Kashian N, Jacobson S. Factors of engagement and patient-reported outcomes in a stage IV breast cancer Facebook group. Health Commun. 2020;35:75–82. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1536962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lepore SJ, Rincon MA, Buzaglo JS, et al. Digital literacy linked to engagement and psychological benefits among breast cancer survivors in internet-based peer support groups. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(4):e13134. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagle N, Painter C, Krevalin M, et al. The Metastatic Breast Cancer Project: a national direct-to-patient initiative to accelerate genomics research. (abstr.) J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(18_suppl):LBA1519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.18_suppl.LBA1519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S. Facebook groups as therapy. [accessed March 1, 2020];The Atlantic. Published October 26, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/10/facebook-emotional-support-groups/572941/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sperber J. Patient driven, patient centered care: examining engagement within a health community based on Twitter. PhD dissertation. [accessed March 1, 2020]. Self-published February 2016. [DOI]