Abstract

Although care of patients with heart failure (HF) has improved in the past decade, important disparities in HF outcomes persist based on race/ethnicity. Age-adjusted HF-related cardiovascular disease death rates are higher for African American patients, particularly among young African Americans whose rates of death are 2.6- and 2.97-fold higher, respectively, than White men and women. Similarly, the rate of HF hospitalization for African American men and women is nearly 2.5-fold higher when compared with whites, with costs that are significantly higher in the first year after HF hospitalization. While the relative rate of HF hospitalization has improved for other race/ethnic minorities, the disparity in HF hospitalization between African American and White patients has not decreased during the last decade. Although access to care and socioeconomic status have been traditional explanations for the observed racial disparities in HF outcomes, contemporary data suggest that novel factors including genetic susceptibility, as well as social determinants of health and implicit bias may play a larger role in health outcomes than previously appreciated. The purpose of this review is to describe the complex interplay of factors that influence racial disparities in HF incidence, prevalence, and disease severity, with a highlight on evolving knowledge that will impact the clinical care, and address future research needs to improve HF disparities in African Americans.

Keywords: heart failure, race/ethnicity, health disparities, African Americans

Subject codes: Heart Failure, Race and Ethnicity, Risk Factors, Mortality/Survival

Compared to other race/ethnic groups, African Americans (AA) have the highest incidence and prevalence of heart failure (HF) as well as the worst clinical outcomes.1-5 While HF is expected to affect almost 3% of Americans by the year 2030, AA will carry the highest burden of disease, with an expected prevalence of ~3.6%.3 The higher burden of HF holds true for both HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), as well as HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Large contemporary analyses demonstrate persistent disparities in HF outcomes for AA, even after differences in traditional cardiovascular (CV) risk factor burden and access to healthcare are taken into account. Moreover, an increasing body of literature reveals unique biologic and social determinants of risk in this population. This review summarizes the key features underlying racial disparities in HF, and addresses future clinical, research, and policy needs to improve HF outcomes in AA.

RACIAL DIFFERENCES IN HF EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLINICAL SEVERITY

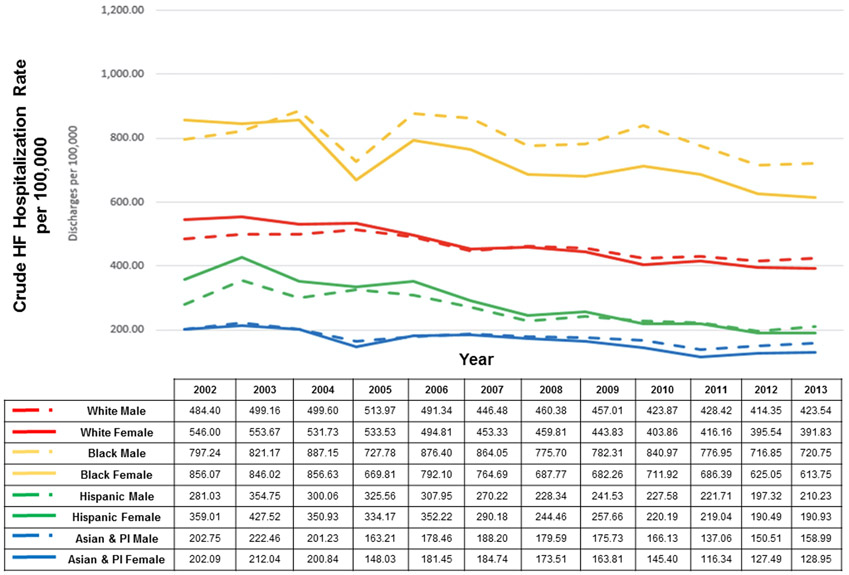

Heart failure (HF) is the leading cause of cardiovascular (CV) hospitalization in the United States (US), and the fifth leading cause of hospitalization overall.1 Although clinical outcomes for patients with HF have improved with advances in medical and device therapies, morbidity and mortality remains high.1, 4, 5 Patients who have experienced a HF hospitalization (HFH) represent those at highest risk for poor clinical outcomes. Thus, treatment of HF and reduction of the burden of HF hospitalizations (HFH) remains a key priority for the medical and scientific community. Moreover, important disparities exist in clinical HF outcomes based on race/ethnicity. African-Americans (AA) have the highest risk of HF-related death (Figure 1).4 Further, the rate of HFH for AA men and women is nearly two and half-fold higher than the rate of HFH for Whites (Figure 2), with costs that are significantly higher in the first year after HFH.5, 6 While the relative rate of HFH has improved for other race/ethnic minorities, the disparity in HFH between AA and White patients has not decreased during the last decade.5 The inferior outcomes in AA with HF is likely due to a complex interplay of biologic determinants that impart unique susceptibility to CVD, coupled with social determinants of health that further worsen racial differences in HF outcomes.

Figure 1.

Age-Adjusted HF-Related CVD Mortality Rates in the US, 1999 to 2017. Death rates per 100,000 by sex and race, note the difference in scale for the Y-axis by age group. Reprinted with permission from Glynn et al.4

Figure 2.

National age-standardized hospitalization rate by race/ethnicity and sex from the National Inpatient Sample. PI indicates Pacific Islander. Reprinted with permission from Ziaeian et al.5

TRADITIONAL AND UNIQUE DETERMINANTS OF HF RISK IN AA

Racial differences in traditional CV risk factors and incidence of HF.

Traditional CV risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are known risk factors for incident HF. The prevalence of each of those risk factors is substantially higher in AA compared to other race-ethnic groups, except for diabetes which has a slightly higher prevalence in Hispanics (Table 1).1, 7 The lower prevalence of healthy lifestyle behaviors in AA contributes to the higher prevalence of CV risk factors in this subgroup. Only 1 in 10 AA have at least 5 CV health metrics at ideal levels, compared to 1.3 in 10 Hispanics, and ~1.8 in 10 non-Hispanic whites.1 Importantly, these disparities may be more prominent among women than men. When examining Life Simple 7 scores among NHANES participants, AA women had significantly lower scores as compared with white women, while differences between AA and white men were relatively small.8 Despite higher body mass index (BMI) and/or ASCVD risk, AA women are less likely than white women to attempt weight loss or to report a healthy diet.9 Importantly, self-perception as overweight is a strong contributor to healthy lifestyle behaviors9, but desired weight and weight self-perceptions vary by race/ethnicity and sex due to important cultural differences in ideal body image. Hair care and maintenance may be a unique barrier to physical activity for AA women in particular, however many clinicians may not feel comfortable addressing this issue with AA patients.10 The higher prevalence of modifiable CV risk factors contributes to the higher prevalence of HF in AA. An analysis of the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study estimated that the preventable fraction of incident HF due to modifiable risk factors was 67.8% (95% CI, 55.1%-76.8%) in AA participants, compared to 48.9% (95% CI, 35.1%-59.8%) in white participants.11 Similarly, an analysis of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study demonstrates that modifiable cardiometabolic risk factors were the strongest predictors of incident HF in AA, including higher diastolic blood pressure and BMI, lower HDL cholesterol, and kidney disease.12

Table 1.

Prevalence of traditional CV risk factors in US adults ≥20 years of age by race-ethnic group and sex.

| Population Group | Hypertension1 | Diabetes1 | Overweight or Obese1 |

Ideal CV Health Metrics8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (both sexes) | 46% | 9.8% | 69.9% | 8.1 (7.8-8.3) |

| NH White | ||||

| • Males | 48.2% | 9.4% | 73.6% | 8.02 (7.73-8.30) |

| • Females | 41.3% | 7.3% | 64.3% | 8.39 (8.08-8.70) |

| NH African American | ||||

| • Males | 58.6% | 14.7% | 69.1% | 7.54 (7.17-7.91) |

| • Females | 56.0% | 13.4% | 79.5% | 7.47 (7.09-7.84) |

| Hispanic | ||||

| • Males | 47.4% | 15.1% | 80.8% | 7.51 (6.91-8.11) |

| • Females | 40.8% | 14.1% | 77.8% | 7.68 (7.36-8.00) |

| NH Asian | ||||

| • Males | 46.4% | 12.8% | 48.8% | NR |

| • Females | 36.4% | 9.9% | 36.3% | NR |

Data taken from Virani et al.1 and Pool et al.8. Data are presented as proportion (%) or mean (confidence interval). Ideal CV health metrics was assigned by giving a score of 0, 1, or 2, corresponding to poor, intermediate, or ideal health, to each of 7 health factors and behaviors (Life’s Simple 7)—diet, physical activity, smoking status, body mass index, blood pressure, blood glucose, and total cholesterol—measured in NHANES participants in 2011-12.

Hypertension as a risk factor for incident HF in AA.

Hypertension is the strongest modifiable population risk factor for HF, and appropriate management of hypertension prevents the onset of HF.13, 14 For example, three quarters of those who developed HF in the CARDIA study had a diagnosis of hypertension by the age of 40.12 Despite higher levels of awareness and treatment of hypertension in AA compared to other race-ethnic groups, however, they are less likely to have their blood pressure (BP) controlled to target.1, 15 An analysis of 8,796 hypertensive adults identified from the NHANES suggests that the difficulty achieving recommended BP targets is not due to inferior treatment (Table 2).15 Compared to whites and Hispanics, AA patients were the most likely to receive combination antihypertensive therapy (including diuretics and calcium channel blockers), and had the highest average number of antihypertensive medications (1.91, 95% CI, 1.84–1.97). Despite this, only 31% of AA patients had their BP controlled to JNC recommended targets, as compared to 43% of whites.

Table 2.

Racial/Ethnic differences in hypertension treatment and control among hypertensive Adults, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2012.

| Hispanic vs White | AA vs White | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Diuretics | 0.55 | (0.45—0.65) | 0.65 | (0.55 – 0.78) | 1.29 | (1.14—1.45) | 1.42 | (1.26 – 1.61) |

| Thiazide diuretics | 0.62 | (0.50—0.75) | 0.76 | (0.62 – 0.94) | 1.29 | (1.14—1.46) | 1.41 | (1.24 – 1.60) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 0.94 | (0.74—1.20) | 1.19 | (0.93 – 1.54) | 1.80 | (1.59—2.04) | 2.13 | (1.86 – 2.44) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 0.88 | (0.73—1.05) | 0.94 | (0.79 – 1.12) | 0.87 | (0.75—1.01) | 0.86 | (0.74 – 0.99) |

| Beta-blockers | 0.64 | (0.54—0.77) | 0.78 | (0.64 – 0.96) | 0.64 | (0.54—0.74) | 0.66 | (0.57 – 0.78) |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 0.77 | (0.62—0.97) | 0.96 | (0.76 – 1.21) | 0.93 | (0.78—1.10) | 1.01 | (0.84 – 1.22) |

| Any hypertensive drug use | 0.54 | (0.44—0.67) | 0.74 | (0.59 – 0.92) | 0.86 | (0.74—0.99) | 0.96 | (0.83 – 1.12) |

| Monotherapy | 0.92 | (0.81—1.06) | 1.02 | (0.88 – 1.17) | 0.74 | (0.65—0.85) | 0.72 | (0.63 – 0.83) |

| Polytherapy | 0.61 | (0.59—0.79) | 0.77 | (0.65 – 0.92) | 1.11 | (0.99—1.24) | 1.29 | (1.14 – 1.47) |

| Hypertension control (JNC 7) | 0.71 | (0.60—0.83) | 0.73 | (0.61 – 0.87) | 0.76 | (0.68—0.86) | 0.73 | (0.63 – 0.83) |

| Hypertension control (JNC 8) | 0.71 | (0.60—0.83) | 0.75 | (0.62 – 0.90) | 0.70 | (0.62—0.78) | 0.69 | (0.60 – 0.79) |

Despite being more likely to receive combination anti-hypertensive therapy, AA patients were less likely to achieve BP control, consistent with the notion that AA patients have more aggressive forms of hypertension. Hispanic patients were also less likely to attain the BP treatment goals compared to Whites, however they received less intensive antihypertensive therapy. Bold denotes statistically significant at P value <0.05. *Among treated patients n=6464 (white: 3435, black: 1819, and Hispanic: 1210). CI indicates confidence interval; JNC, Joint National Committee; OR, odds ratio. Reprinted with permission from Gu et al.15

The difficulty achieving BP targets in AA may be related to underlying racial differences in vascular function. Multiple prior studies have demonstrated that AA have impaired endothelium-dependent and –independent vasodilation compared to whites.16-18 Endothelial cells of AA appear to generate more oxidant stress, leading to enhanced inactivation of the potent vasodilator nitric oxide (NO).19 This diminished response to endogenous and exogenous NO in AA likely contributes to the more severe hypertension, and hypertensive HF, in the AA population. Moreover, AA display more adverse changes in cardiac structure and function in response to arterial stiffness compared to whites, indicating a greater vulnerability of the myocardium to the effects of arterial stiffness and vascular dysfunction. An analysis of 5,727 subjects in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Community (ARIC) study demonstrated greater arterial afterload in AA compared to whites, measured as higher systemic vascular resistance and reduced arterial compliance.20 Arterial afterload was more strongly associated with increased left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic volumes, LV mass, and worse diastolic function in AA. Moreover, the association of arterial afterload with adverse changes in cardiac structure were stronger in AA with a greater proportion of African genetic ancestry. Epidemiologically, multiple studies have documented an increased prevalence of LV hypertrophy (LVH) in AA even after adjusting for other CV risk factors.21, 22 Moreover, the population attributable risk of incident HF is higher in AA men and women than in whites due to a markedly higher prevalence of malignant LVH (LVH associated with abnormal levels of cardiac troponin and NT-proBNP).22

Racial differences in prevalence of rare genetic variants associated with incident HF.

Increasing use of population-based genome-sequencing studies has identified variation in alleles and their frequency that may be associated with racial differences in incident HF.

Compared to Whites, AA have ~3-fold increased risk for developing DCM, and ~2-fold increased risk of death after diagnosis that is not explained by socioeconomic status (SES) and hypertension.2 A recent GWAS performed in a AA cohort estimated the heritability of DCM to be 33% (compared to 18% for HF in Framingham offspring23), and identified a novel intronic locus in the CACNB4 gene which encodes a calcium channel subunit essential to cardiac muscle contraction.24 An analysis of subjects with DCM identified 4 unique genetic variants in BAG3 found almost exclusively in AA subjects, and were associated with an approximately 2-fold higher risk of death or HFH.25 Importantly, the 4 variants identified in this analysis were annotated as benign, likely benign, or of indeterminate pathogenicity in a widely used public database of genomic information, which may be due in part to the overall lack of data on subjects of African ancestry in genetic studies.

Studies of women with peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) demonstrate that AA women have a more severe disease profile, including younger age at onset, more severe LV dysfunction at initial presentation, and lower rates of LV recovery.26, 27 In a multinational cohort of women with PPCM, the prevalence of truncating variants (including titin [TTNtv]) was similar to that observed in a cohort of patients with DCM, suggesting a potential genetic etiology for PPCM.28 Moreover, the prevalence of TTNtv was higher in women of African ancestry compared to those of European ancestry.28 In a series of 220 women with PPCM from a single center, AA were less likely than non-AA women to recover their EF to >50%.27 Even among those women with LVEF recovery, the rate of recovery was twice as slow for AA women despite equivalent prescription of ACEi and beta-blockers between racial groups.

The hereditary form of transthyretin (TTR)-related cardiac amyloidosis disproportionately affects AA, as the valine-to-isoleucine substitution (V122I) at position 122 on chromosome 18 is carried by 3-5% of AA.29, 30 Despite widespread recognition that the V122I variant is strongly associated with the risk of HF, few AA subjects are recognized as having aTTR-related cardiomyopathy or undergo genetic testing for aTTR in routine clinical practice.30, 31 Underrecognition of aTTR-related disease in AA may be, in part, due to the high prevalence of co-occuring disorders associated with LVH, including hypertension, obesity, and diabetes. Nonetheless, the increasing number of novel therapies being studied for treatment of aTTR cardiac amyloidosis raises the imperative to ensure that AA receive appropriate diagnostic testing to identify this condition.

The high prevalence of LVH in AA may also be associated with difficulty diagnosing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). In one series of 1900 patients referred to a specialty HCM program, AA patients more commonly had an uncertain diagnosis of HCM, were less likely to be referred for risk stratification of sudden death, and were less likely to have implanted cardioverter-defibrillators.32 Another multicenter series of 2,467 patients with HCM demonstrate that AA patients were less likely than whites to undergo genetic testing.33 Moreover, AA were less likely to have a pathogenic or likely pathogenic sarcomeric mutation identified, and were more likely to have a variant of unknown significance.

Although many of the aforementioned studies also showed a higher prevalence of traditional CV risk factors including hypertension and diabetes in the enrolled AA subjects, the presence of traditional CV risk factors should not preclude the use of genetic testing, as the concomitant presence of underlying genetic variants with traditional risk factors may explain the earlier onset of disease in many AA patients. Wider adoption of genetic testing in diverse populations is necessary, as a thorough understanding of the contribution of genomic variation to disease is particularly relevant for conditions in which the disease burden is disproportionately high.

Relative deficiency of natriuretic peptides in AA.

Natriuretic peptides (NP) are produced in response to increased cardiac wall tension and stress, and have various protective cardiometabolic effects, including vasodilation and promotion of natriuresis and diuresis.34 Animal studies have documented impaired production of NP promotes salt-sensitive hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy.35, 36 Thus, a relative deficiency of NP may be associated with multiple adverse phenotypes, including LVH, salt and fluid retention, and hypertension.37 Multiple analyses have documented lower levels of NP in AA subjects without HF. AA subjects enrolled in the Dallas Heart Study and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), who were free of CVD at the time of enrollment, demonstrated lower NT-proBNP levels compared to whites.37, 38 Moreover, genetic ancestry informed the lower NT-proBNP levels, such that a 20% increase in African ancestry was associated with a ~10% decrease in NT-proBNP levels among self-reported AA and Hispanic participants in MESA.38 Thus, there appear to be genetic underpinnings contributing to the lower NP levels in AA.

AA have a high prevalence of salt sensitivity that is known to contribute to adverse CV outcomes.

Strictly speaking, salt sensitivity is a physiologic trait whereby BP exhibits changes parallel to changes in salt intake.39 Although the mechanisms are poorly understood, it is thought that the elevation in BP exhibited by salt sensitive individuals after a sodium load is required to induce a pressure natriuresis. Salt sensitivity is thought to be present in up to 75% of hypertensive AA and some normotensive AA.40-42 Moreover, the salt sensitive phenotype is characterized by low renin and aldosterone levels, suggesting that the associated hemodynamic alterations are not directly secondary to increased RAAS activity.43 Alternate mechanisms for sodium retention in AA have not been well defined, but may include reduced potassium intake, decreased urinary kallikrein excretion, upregulation of epithelial sodium channel activity, deficiencies in natriuretic production, and APOL1 gene nephropathy risk variants.37, 38 Racial differences in activity of the RAAS may also be relevant in patients with HF. In a small sample of AA patients with chronic ambulatory HF, higher proportion of African ancestry was associated with lower aldosterone levels, while higher proportion of European ancestry was associated with higher levels.44 A recent post-hoc analysis of data from 3 acute HF clinical trials demonstrated that AA with acute HF have lower levels of plasma renin activity and aldosterone than non-AA.45 Moreover, plasma renin activity was related to racial differences in diuretic efficiency, and the risk for rehospitalization. Additional studies are needed to examine racial differences in sodium and fluid homeostasis in subjects with acute and chronic HF.

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HF SUSCEPTIBILITY AND OUTCOMES

Neighborhood and residential environment.

The economic and racial segregation created by “redlining”, a practice implemented by US federal agencies in the 1930s that continued until the 1970s, has resulted in persistent economic inequality that can be documented even today.46 In addition to the economic inequalities, it also clear that persons living in more impoverished and racially-segregated neighborhoods are more likely to develop incident CVD and HF even after adjusting the burden of traditional CV risk factors, suggesting that neighborhood-related risks for poor CV outcomes are not fully explained solely by the higher burden of CV risk factors.47-49 An analysis of 27,078 AA and white participants in the Southern Community Cohort Study showed that each interquartile increase in neighborhood deprivation was associated with a 12% increase in incident HF.48 Similarly, living in a food desert, defined as low-income areas with low access to healthful foods, was associated with an increased risk of repeat all-cause and HF hospitalizations.50 The association between neighborhood deprivation and CVD risk may be mediated in part through environmental factors that negatively impact on patients’ ability to engage in healthy lifestyle behaviors and self-care. For example, commercial facilities for physical activity are less likely to exist in neighborhoods with lower-income or higher proportions of race/ethnic minorities.51 A lack of neighborhood walkability and green space can increase sedentary lifestyle and physical inactivity.52-54 Multiple studies have demonstrated that low-income and predominantly AA neighborhoods have fewer supermarkets or specialty food stores than high-income or predominantly white neighborhoods, such that there is a lower availability of fresh, healthy foods.55 Thus. the cumulative effects of neighborhood deprivation may be particularly deleterious for race-ethnic minorities.

Implicit bias as a determinant of quality of healthcare.

Implicit bias refers to unconscious attitudes or stereotypes that involuntarily affect our understanding and actions. Prior studies have documented that implicit bias can affect the clinical decision-making of health care providers, including the acute care of AA patients with HF from the emergency department to the intensive care unit (ICU). Lo et al. examined >12 million adult visits to US emergency departments from 2001-2010 with a chief complaint related to HF symptoms.56 Among all non-ICU admissions, AA were less likely to be hospitalized than whites, even among older patients with higher levels of acuity. Another analysis of admissions for HF at a single, quarternary care academic center noted that AA and Latinx HF patients were 9% and 17% less likely to be admitted to a cardiology service from the ED than white patients.57 Unfortunately, disparate access to a cardiologist appears to persist for AA HF patients even when managed in an ICU setting. In an examination of 104,835 patients that required ICU admission for a primary diagnosis of acute HF, AA were less likely to be seen by a cardiologist during their ICU stay.58 Of note, patients who receive care from a cardiologist have better clinical outcomes, including increased in-hospital survival and decreased likelihood of 30-day readmission.57, 58 Even for patients with access to advanced HF care, there may be subtle differences in the choice of advanced HF therapy. A recent study presented clinical vignettes describing an end-stage HF patient to 422 advanced HF clinicians, of whom 42 were probed about their decision making strategy during an intensive “think-aloud” interview.59 The interviews revealed a number of themes that influenced disparate decision making, including greater concern for trust and adherence for the AA patient, and a sense that the AA patient was sicker, ultimately resulting in the AA patient being less likely to be offered HT and more likely to be offered LVAD. These findings are notable, particularly providers’ greater concerns for noncompliance among the AA patient, a finding that has been documented in multiple other studies where case vignettes were presented to clinicians with every detail about the patient being identical (medical history, description of symptoms, etc) except for the race of the patient.60, 61

CHALLENGES FOR IMPROVING TREATMENT OF AA WITH HF

Prevention of HF.

The onset of HF can be substantially postponed, or prevented altogether with targeted prevention of CV risk factors. Incident HF in AA in the CARDIA cohort occurred at an average age of 39 years, and was predicted by the presence of hypertension, obesity, CKD and depressed systolic function 10–15 years prior to HF onset.12 Similarly, a prior analysis of 2,934 participants in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study suggested that the preventable fraction of incident HF in this elderly cohort was 67.8% in AA and 48.9% in Whites.11 For AA in this cohort, the preventable fraction of incident HF associated with systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg was 30.1%, and was 19.5% for LVH. Interestingly, the association of LVH with incident HF (which was present even in 8.6% of AA subjects with systolic BP < 140 mm Hg) was additive to and independent of the risk due to uncontrolled hypertension, which may be an indicator of the presence of undiagnosed cardiac amyloidosis in this elderly cohort. Due to the greater morbidity and mortality associated with hypertension in AA, current guidelines for treatment of hypertension in adults incorporate race-specific recommendations including the initial use of thiazide-type diuretics or calcium channel blockers, as well as the use of two or more antihypertensive medications.62

Improved utilization of guideline directed medical therapy.

The landscape of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for HF is rapidly changing, with novel therapies including angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, and other drugs showing substantial improvements in morbidity and mortality. Current guidelines for the treatment of stage C HFrEF also include the use of combination therapy with hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate (H-ISDN) as a Class I recommendation for AA with HF.63 It has been postulated that the improvement in outcomes in AA treated with H-ISDN is due to the theory that this drug combination improves the biologic underpinnings of reduced NO bioavailability in AA. ISDN is an organic nitrate that stimulates NO signaling and bioavailability, and H is a vasodilator and antioxidant that inhibits the enzymatic formation of reactive oxygen species and ameliorates excess oxidative stress. Despite this, H-ISDN is widely underutilized in eligible AA with HF.64-66 There has been widespread concern related to adherence, as use may be limited by three times a day dosing as well as the side effect profile.67 However, Callier et al. conducted semistructured interviews with 81 cardiologists attending an annual scientific meeting to explore their attitudes towards race-based guidelines.68 Nearly half of participants expressed skepticism or strongly disapproved of race-based drug labels and the use of race in drug prescribing. Participants expressed concern about the impact of admixture, and that race-based labeling may prohibit the drug from being prescribed to non-AA patients who may also benefit. Increased use of precision medicine may help determine which patients derive the most benefit from H-ISDN, irrespective of race/ethnicity. The Genetic Risk Assessment of HF substudy of A-HeFT has demonstrated polymorphisms in the guanine nucleotide-binding proteins beta-3 subunit, endothelial NO synthase, and aldosterone synthase that are associated with greater therapeutic effect of fixed dose H-ISDN.69-71 For example, although the −344T>C polymorphism in the promoter region of the aldosterone synthase gene may be associated with higher aldosterone levels, as well as increased risk of atrial fibrillation and HFH, the CC genotype is less prevalent in AA and may correlate with greater percent European ancestry.44, 71

Although data on race-based utilization of novel therapies is somewhat limited, many registries show that prescription of standard GDMT including ACEI/ARB, beta-blocker and MRA is comparable among blacks and whites with HF.65, 72, 73 In the CHAMP-HF registry, dosing and titration of GDMT is suboptimal regardless of race/ethnicity.72, 74 AA were equally as likely to be treated with ARNI as whites, however few AA patients received both ARNI and H-ISDN.65, 72 Currently, there is little data on real-world use of SLGT2 inhibitors for HF. Future research should monitor race-based differences in patterns of utilization; despite the high burden of diabetes in AA patients, a recent retrospective analysis of claims data on >1,000,000 US adults with diabetes showed that AA were less likely than whites to be started on SGLT2i.75

Improved utilization of advanced therapies for HF.

Although the number of AA patients receiving advanced HF therapies appears to be growing 76, 77, it is unclear whether the growth is proportional to the number of AA patients affected by HF. A recent analysis of the Interagency Registry of Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support indicates per capita LVAD implantation rates for AA did not increase proportionally with increases in HF incidence, suggesting continued racial disparities.77 There are a number of reasons why AA may be underrepresented as recipients of advanced HF therapies, including underinsurance, lack of social support, and other factors. Moreover, AA hospitalized with acute HF are less likely to be treated by a cardiologist than non-AA patients, which may have a direct impact on the likelihood of recognition of stage D HF and need for advanced therapies. 57, 58

Lack of inclusion of minorities in clinical trials.

While AA are overrepresented in the incidence and prevalence of HF, they are underrepresented in the clinical trials used to determine treatment.78 Recent data demonstrate that trial-eligible patients in real-world clinical settings have worse clinical outcomes than patients enrolled in clinical trials.73 The worse outcomes are driven in part by differences among AA and women, suggesting that more research is needed to understand the complex social and behavioral factors that are not measured in most contemporary CV trials. Although the National Institutes of Health requires investigators to explicitly address their approach for prospective enrollment of women and minorities in all human subjects research, no such requirement exists for the pharmaceutical industry. Moreover, large and costly trials are often performed without adequate numbers of minority patients, such that conclusions regarding the effectiveness of new medications in the populations who have the greatest potential to benefit are based on post-hoc analyses. The low participation of AA in clinical trials may in part be patient-driven due to mistrust of the healthcare system, and may in part be provider-driven as prior studies have documented that AA are more likely to perceived as noncompliant, and that physicians are less likely to discuss new and alternative therapies with AA patients.59, 79 Future studies should continue to prioritize adequate representation of race-ethnic minorities as trial participants to ensure generalizability of findings to the most vulnerable populations.

Financial toxicity of novel medical and device therapies.

Recent FDA approval of novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of HF has thrust drug costs to the forefront of conversations about shared decision-making. The out-of-pocket costs and “financial toxicity” of novel HF drugs limit access to effective therapies and may negatively impact medication adherence. Although most analyses have determined that novel drugs are cost-effective for the healthcare system, few studies have analyzed patients’ actual out-of-pocket drug costs. An analysis of projected out-of-pocket costs for Medicare part D plans estimates expenditures as high as $1,685 annually for ARNI (nearly $1,400 more than those prescribed an ARB), with monthly costs exceeding $160 during the coverage gap.80 This magnitude of monthly cost for one therapy may be quite meaningful to patients, particularly when polypharmacy for multiple comorbid conditions is taken into account. Smith et al. conducted structured interviews with 49 HFrEF patients, and determined that only 43% would want to switch to sacubitril-valsartan if their out-of-pocket cost was $100 more per month than their current costs, compared to 92% who said that they would definitely or probably switch if their out-of-pocket cost was $5 more per month.81 Importantly, only 20% of participants in this study said their physician had initiated a conversation about cost with them in the past year. Currently, there are limited data on whether cost differentially impacts utilization of novel HF therapies according to race/ethnicity. Given the widespread socioeconomic differences that exist according to race/ethnicity, future research should capture how patient access to GDMT varies based on drug cost, SES, and race.

KEY AREAS FOR IMPROVEMENT

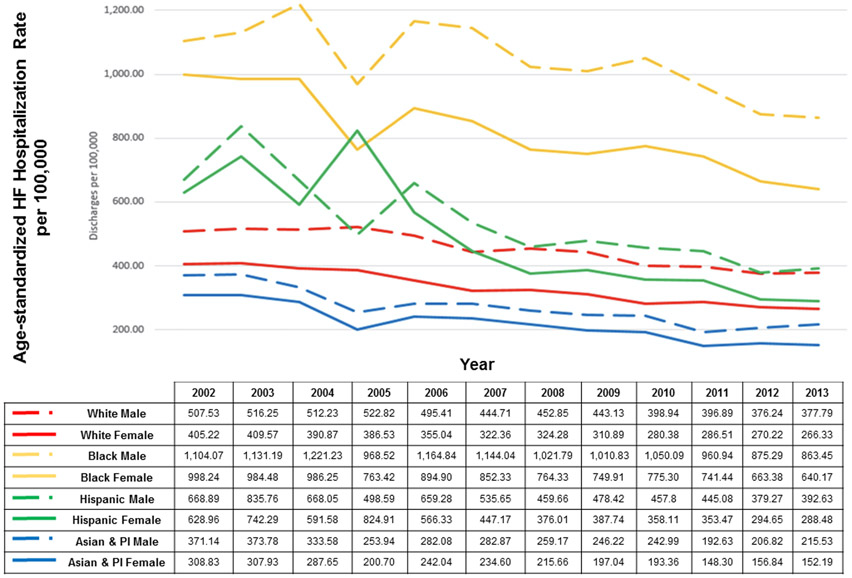

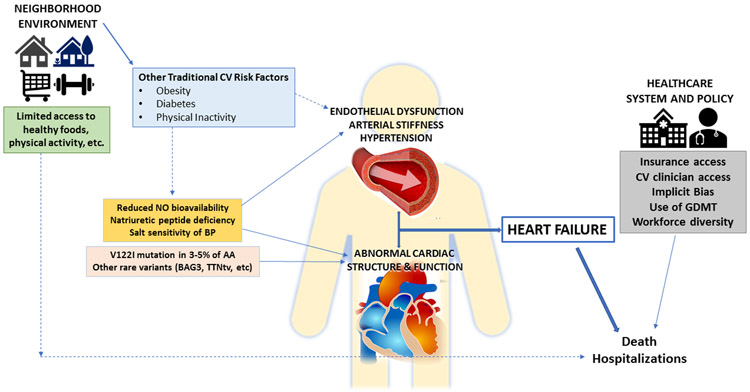

Although this list is not all-encompassing, the multitude of factors influencing racial disparities in HF incidence and outcomes are summarized in Figure 3. Since the causes for the existence of health disparities are multifactorial, the solutions for the elimination of health disparities will need to be multifactorial as well. Each factor can be viewed as an opportunity for intervention to improve the treatment of HF in AA to reduce disparities. Disparities can only be eliminated through concerted efforts to increase knowledge of determinants of differences in disease burden, differences in response to treatment of disease, and to improve contextual factors that influence clinical outcomes. The social ecological model is a framework that emphasizes the multiple levels of influence that impact patients’ behaviors and clinical outcomes.82 The social ecological model acknowledges the relevance of biological and genetic aspects of an individual’s risk for disease, but puts those risks into the context of interpersonal, community, and societal factors to allow clinicians and researchers to understand the range of factors that influence an individual’s outcomes. This type of framework allows the visualization of key areas that must be targeted to improve race-ethnic disparities in HF, so that collecting data on the multiple levels of risk will improve understanding and facilitate implementation of multi-level prevention strategies (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Multiple levels of influence on racial disparities in HF incidence and clinical outcomes once clinical disease is manifest.

Figure 4.

Targets for improving racial HF disparities utilizing the framework of the social-ecological model.

Traditional clinical trials and treatment guidelines focus primarily on the individual patient. Focusing on the management of individual CV risk factors, particularly hypertension, obesity and physical inactivity, continues to be one of the most important strategies to control the incidence of HF in AA. Clinicians need to be aware of and provide culturally sensitive recommendations for barriers to implementing therapeutic lifestyle changes that may be uniquely present for AA patients (for example, haircare and lack of available neighborhood resources as barriers to exercise).10, 51 Increasing clinician awareness that AA patients with significant LVH, particularly if LVH is present in the setting of relatively well controlled BP, warrant a clinical investigation to rule out cardiac amyloidosis.30 Given the rapid growth of novel medical and device therapies becoming available for HF, encouraging minority patients to participate in clinical trials should be a high priority for all clinicians, as patients may be more likely to participate in research studies at the urging of their primary clinician. Improving academic-community partnerships could also help attract patients and family members who are primarily followed in community settings to consider referral for inclusion in clinical trials. Identifying methods to improve shared decision-making and discussions about the potential financial costs of novel therapies should also be a priority for clinicians during clinic encounters. Clinicians can also help to assist patients with building strong bonds at the interpersonal level, by encouraging family based genetic counseling for HF risk.83 In addition, educating patients to discuss the medical severity of their HF with loved ones may give families time to openly discuss care plans and social support options for advanced HF therapies before the patient is in critical cardiogenic shock.

Although changes at the community level may be outside of the control of the healthcare providers, clinicians must be aware of the unique challenges present for patients who live in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods. Voucher programs have been successfully used to improved patients’ access to healthy foods, recreational exercise facilities, and even higher quality housing.84-87 For example, Trapl et al. utilized a “produce prescription program” to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among 224 patients (mean age 62 years, 97% AA) with hypertension at a safety net clinic.85 Patients had 3 clinic visits at monthly intervals, where they received a BP check, targeted nutrition counselling, and were given vouchers to purchase fresh produce at farmers markets. Eighty-six percent visited a farmers market to purchase produce using their vouchers; at the end of the follow-up period, significant improvement in fruit and vegetable consumption and decline in fast food consumption was observed. In order to fully understand the impact of community-level and neighborhood deprivation on health behaviors and outcomes, many have advocated for integrating social determinants of health including neighborhood composition and characteristics, food and housing insecurity, behavior and lifestyle patterns, and other factors into the electronic medical record as well as prospective research activities.49, 88

At the organizational level, there are ample opportunities for improving coordinated care of AA patients with HF. Algorithms embedded into the electronic medical record could be useful for implementation of various quality metrics, including screening for genetic causes of cardiomyopathy based on clinical criteria (i.e. severity of LVH to screen for amyloidosis), automatic inpatient cardiology consultations and/or referrals to specialty HF clinics based on the number of prior hospitalizations and/or 30-day readmissions, or medication adjustments to ensure that evidence-based GDMT is being prescribed and appropriately titrated for all patients.74, 89 Similarly, organizational policies requiring implicit bias training for clinicians may be an effective method to educate providers on how implicit bias impacts clinical decision-making. Diversification of the workforce and increasing community outreach can help reduce disparities, as prior research has shown that increasing the number of doctors who are race/ethnic minorities can improve adherence and the quality of communication experienced by patients, while administering care in non-traditional settings in the community (i.e. barbershops) can also improve clinical outcomes.90-92

At the policy level, there are multiple examples of legislation that have resulted in tangible health consequences for AA patients. Inadequate access to healthcare has long been recognized as having a disproportionate impact on the health of AA. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) increased the proportion of Americans with health insurance, with proportionally greater gains for race/ethnic minorities.93 Since adoption of the ACA, rates of HT listing and LVAD implantation increased for AA patients in states that were “early adopters” of Medicaid expansion, confirming policies that improve access also improve clinical outcomes.94, 95 The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) was intended to reduce 30-day hospital readmissions by increasing accountability of patient care organizations, improving the quality of care, and enhancing care coordination particularly at the time of discharge. However, there is evidence that the HRRP disproportionately penalizes safety-net hospitals that serve greater proportions of race-ethnic minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged patients, which has the potential to actually worsen existing disparities.96 Ongoing efforts seek to improve the risk adjustment algorithms by taking socioeconomic and societal factors into account, to ensure that minority-serving and safety-net hospitals do not incur excessive payment penalties, as excess readmissions for these hospitals may also be influenced by aspects of the post-discharge environment that are beyond the control of the hospital or its providers.96, 97

Novel policies should also be employed to improve the state of funding for healthcare disparities research. Recent data shows that AA applicants for NIH research funding are less likely to be funded even after controlling for educational background, previous research awards, publication record, and other factors.98, 99 A follow-up analysis demonstrates that topic choice may be the largest driver of that funding gap, since AA investigators are more likely to propose research on health disparities, and to use study designs that included humans, communities, and behavioral interventions.99 The authors of this pivotal study speculated that disparities research may be “less likely to excite the enthusiasm” of study sections and reviewers compared to other topics. In a recent editorial, Carnethon et al. proposed several methods that could be used by the NIH to improve funding rates for health disparities research including: 1) involve health disparities experts on every study section, 2) continue to improve the race/ethnic diversity of the pool of peer reviewers, 3) designate a proportion of funding within each NIH institute research portfolio that must address health disparities topics, and 4) expand efforts to support diversity-focused science by creating programs that target funding toward investigators who are studying health disparities.100

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the ever-growing portfolio of scientific literature describing the existence of health disparities, the healthcare community continues to struggle to find viable methods to effectively eliminate disparities. The exquisite complexity of factors that impact the persistence of health disparities, ranging from genetics, to CV risk factor burden, to social determinants of health that affect lifestyle and health behaviors, to implicit bias that may affect treatment recommendations, present a challenge of epic proportion for the medical community to tackle. Still, we must meet that challenge head on, by continuing to encourage research initiatives, quality metrics, clinical trial enrolment, reporting of results, as well as patient education and engagement that are sensitive to race and ethnic differences in the manifestations of CVD. Preventing adverse clinical outcomes in HF is not only crucial for patients’ well-being and quality of life, but has become an increasing priority for clinicians, hospitals, and payers in the post-HRRP era. Prioritizing culturally sensitive healthcare and health equity with a goal of eliminating health disparities is one obvious way to satisfy all of the relevant stakeholders, particularly our minority patients who stand to gain the most.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Khadijah Breathett MD, MSc for helping to conceive of this project.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Dr. Morris has received research grants from NHLBI (NIH K23 HL124287 and R03 HL146874), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program), and the Woodruff Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, Lewis TT, Lichtman JH, Longenecker CT, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Martin SS, Matsushita K, Moran AE, Mussolino ME, Perak AM, Rosamond WD, Roth GA, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Shay CM, Spartano NL, Stokes A, Tirschwell DL, VanWagner LB and Tsao CW. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update. Circulation. 2020;0:CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozkurt B, Colvin M, Cook J, Cooper LT, Deswal A, Fonarow GC, Francis GS, Lenihan D, Lewis EF and McNamara DM. Current diagnostic and treatment strategies for specific dilated cardiomyopathies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e579–e646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, Ikonomidis JS, Khavjou O, Konstam MA, Maddox TM, Nichol G, Pham M, Piña IL and Trogdon JG. Forecasting the Impact of Heart Failure in the United States. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2013;6:606–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glynn P, Lloyd-Jones DM, Feinstein MJ, Carnethon M and Khan SS. Disparities in Cardiovascular Mortality Related to Heart Failure in the United States. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73:2354–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziaeian B, Kominski GF, Ong MK, Mays VM, Brook RH and Fonarow GC. National Differences in Trends for Heart Failure Hospitalizations by Sex and Race/Ethnicity. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2017;10:e003552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziaeian B, Heidenreich PA, Xu H, DeVore AD, Matsouaka RA, Hernandez AF, Bhatt DL, Yancy CW and Fonarow GC. Medicare Expenditures by Race/Ethnicity After Hospitalization for Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC: Heart Failure. 2018;6:388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carnethon MR, Pu J, Howard G, Albert MA, Anderson CAM, Bertoni AG, Mujahid MS, Palaniappan L, Taylor HA, Willis M and Yancy CW. Cardiovascular Health in African Americans: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136:e393–e423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pool LR, Ning H, Lloyd-Jones DM and Allen NB. Trends in Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cardiovascular Health Among US Adults From 1999–2012. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017;6:e006027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris AA, Ko YA, Hutcheson SH and Quyyumi A. Race/Ethnic and Sex Differences in the Association of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk and Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018;7:e008250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tolliver SO, Hefner JL, Tolliver SD and McDougle L. Primary Care Provider Understanding of Hair Care Maintenance as a Barrier to Physical Activity in African American Women. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2019;32:944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalogeropoulos A, Georgiopoulou V, Kritchevsky SB, Psaty BM, Smith NL, Newman AB, Rodondi N, Satterfield S, Bauer DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Smith AL, Wilson PWF, Vasan RS, Harris TB and Butler J. Epidemiology of Incident Heart Failure in a Contemporary Elderly Cohort: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169:708–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM, Arynchyn A, Lewis CE, Williams OD and Hulley SB. Racial Differences in Incident Heart Failure among Young Adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:1179–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Upadhya B, Rocco M, Lewis CE, Oparil S, Lovato LC, Cushman WC, Bates JT, Bello NA, Aurigemma G, Fine LJ, Johnson KC, Rodriguez CJ, Raj DS, Rastogi A, Tamariz L, Wiggers A and Kitzman DW. Effect of Intensive Blood Pressure Treatment on Heart Failure Events in the Systolic Blood Pressure Reduction Intervention Trial. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2017;10:e003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Blood pressure-lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. The Lancet. 2014;384:591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu A, Yue Y, Desai Raj P and Argulian E. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Antihypertensive Medication Use and Blood Pressure Control Among US Adults With Hypertension. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2017;10:e003166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campia U, Choucair WK, Bryant MB, Waclawiw MA, Cardillo C and Panza JA. Reduced endothelium-dependent and -independent dilation of conductance arteries in African Americans. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;40:754–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozkor M, Rahman A, Murrow J, Kavtaradze N, Lin J, Manatunga A and Quyyumi A. Greater Contribution of Endothelium-Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor to Exercise-Induced Vasodilation in African Americans Compared to Whites. Circulation. 2010;122:A13694. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris AA, Patel RS, Binongo JN, Poole J, Al Mheid I, Ahmed Y, Stoyanova N, Vaccarino V, Gibbons GH and Quyyumi A. Racial Differences in Arterial Stiffness and Microcirculatory Function Between Black and White Americans. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2:e002154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalinowski L, Dobrucki IT and Malinski T. Race-Specific Differences in Endothelial Function: Predisposition of African Americans to Vascular Diseases. Circulation. 2004;109:2511–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandes-Silva MM, Shah AM, Hegde S, Goncalves A, Claggett B, Cheng S, Nadruz W, Kitzman DW, Konety SH, Matsushita K, Mosley T, Lam CSP, Borlaug BA and Solomon SD. Race-Related Differences in Left Ventricular Structural and Functional Remodeling in Response to Increased Afterload: The ARIC Study. JACC: Heart Failure. 2017;5:157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drazner MH, Dries DL, Peshock RM, Cooper RS, Klassen C, Kazi F, Willett D and Victor RG. Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Is More Prevalent in Blacks Than Whites in the General Population. Hypertension. 2005;46:124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis AA, Ayers CR, Selvin E, Neeland I, Ballantyne C, Nambi V, Pandey A, Powell-Wiley TM, Drazner MH, Carnethon MR, Berry JD, Seliger SL, deFilippi CR and de Lemos JA. Racial Differences in Malignant Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Incidence of Heart Failure: A Multi-Cohort Study. Circulation. 2020;141:957–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee DS, Pencina MJ, Benjamin EJ, Wang TJ, Levy D, O'Donnell CJ, Nam BH, Larson MG, D'Agostino RB and Vasan RS. Association of parental heart failure with risk of heart failure in offspring. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355:138–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu H, Dorn GW 2nd, Shetty A, Parihar A, Dave T, Robinson SW, Gottlieb SS, Donahue MP, Tomaselli GF, Kraus WE, Mitchell BD and Liggett SB. A Genome-Wide Association Study of Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy in African Americans. J Pers Med. 2018;8:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers VD, Gerhard GS, McNamara DM, Tomar D, Madesh M, Kaniper S, Ramsey FV, Fisher SG, Ingersoll RG, Kasch-Semenza L, Wang J, Hanley-Yanez K, Lemster B, Schwisow JA, Ambardekar AV, Degann SH, Bristow MR, Sheppard R, Alexis JD, Tilley DG, Kontos CD, McClung JM, Taylor AL, Yancy CW, Khalili K, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, McTiernan CF, Cheung JY and Feldman AM. Association of Variants in BAG3 With Cardiomyopathy Outcomes in African American Individuals. JAMA cardiology. 2018;3:929–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNamara DM, Elkayam U, Alharethi R, Damp J, Hsich E, Ewald G, Modi K, Alexis JD, Ramani GV, Semigran MJ, Haythe J, Markham DW, Marek J, Gorcsan J 3rd, Wu W-C, Lin Y, Halder I, Pisarcik J, Cooper LT, Fett JD; IPAC Investigators. Clinical Outcomes for Peripartum Cardiomyopathy in North America: Results of the IPAC Study (Investigations of Pregnancy-Associated Cardiomyopathy). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015;66:905–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irizarry OC, Levine LD, Lewey J, Boyer T, Riis V, Elovitz MA and Arany Z. Comparison of Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Peripartum Cardiomyopathy Between African American and Non-African American Women. JAMA cardiology. 2017;2:1256–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware JS, Li J, Mazaika E, Yasso CM, DeSouza T, Cappola TP, Tsai EJ, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Kamiya CA, Mazzarotto F, Cook SA, Halder I, Prasad SK, Pisarcik J, Hanley-Yanez K, Alharethi R, Damp J, Hsich E, Elkayam U, Sheppard R, Kealey A, Alexis J, Ramani G, Safirstein J, Boehmer J, Pauly DF, Wittstein IS, Thohan V, Zucker MJ, Liu P, Gorcsan J, McNamara DM, Seidman CE, Seidman JG and Arany Z. Shared Genetic Predisposition in Peripartum and Dilated Cardiomyopathies. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:233–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quarta CC, Buxbaum JN, Shah AM, Falk RH, Claggett B, Kitzman DW, Mosley TH, Butler KR, Boerwinkle E and Solomon SD. The Amyloidogenic V122I Transthyretin Variant in Elderly Black Americans. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;372:21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah KB, Mankad AK, Castano A, Akinboboye OO, Duncan PB, Fergus IV and Maurer MS. Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis in Black Americans. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2016; 9:e002558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damrauer SM, Chaudhary K, Cho JH, Liang LW, Argulian E, Chan L, Dobbyn A, Guerraty MA, Judy R, Kay J, Kember RL, Levin MG, Saha A, Van Vleck T, Verma SS, Weaver J, Abul-Husn NS, Baras A, Chirinos JA, Drachman B, Kenny EE, Loos RJF, Narula J, Overton J, Reid J, Ritchie M, Sirugo G, Nadkarni G, Rader DJ and Do R. Association of the V122I Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis Genetic Variant With Heart Failure Among Individuals of African or Hispanic/Latino Ancestry. JAMA. 2019;322:2191–2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells S, Rowin EJ, Bhatt V, Maron MS and Maron Barry J. Association Between Race and Clinical Profile of Patients Referred for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2018;137:1973–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eberly LA, Day SM, Ashley EA, Jacoby DL, Jefferies JL, Colan SD, Rossano JW, Semsarian C, Pereira AC, Olivotto I, Ingles J, Seidman CE, Channaoui N, Cirino AL, Han L, Ho CY and Lakdawala NK. Association of Race With Disease Expression and Clinical Outcomes Among Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JAMA cardiology. 2019;5:83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang TJ. The Natriuretic Peptides and Fat Metabolism. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:377–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.John SW, Krege JH, Oliver PM, Hagaman, Hodgin JB, Pang SC, Flynn TG and Smithies O. Genetic decreases in atrial natriuretic peptide and salt-sensitive hypertension. Science. 1995;267:679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Cui Y, Shen J, Jiang J, Chen S, Peng J and Wu Q. Salt-sensitive hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice expressing a corin variant identified in blacks. Hypertension. 2012;60:1352–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta DK, de Lemos JA, Ayers CR, Berry JD and Wang TJ. Racial Differences in Natriuretic Peptide Levels: The Dallas Heart Study. JACC: Heart Failure. 2015;3:513–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta DK, Daniels LB, Cheng S, deFilippi CR, Criqui MH, Maisel AS, Lima JA, Bahrami H, Greenland P, Cushman M, Tracy R, Siscovick D, Bertoni AG, Cannone V, Burnett JC, Carr JJ and Wang TJ. Differences in Natriuretic Peptide Levels by Race/Ethnicity (From the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). The American Journal of Cardiology. 2017;120:1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elijovich F, Weinberger Myron H, Anderson Cheryl AM, Appel Lawrence J, Bursztyn M, Cook Nancy R, Dart Richard A, Newton-Cheh Christopher H, Sacks Frank M and Laffer Cheryl L. Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2016;68:e7–e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grim CE, Miller JZ, Luft FC, Christian JC and Weinberger MH. Genetic influences on renin, aldosterone, and the renal excretion of sodium and potassium following volume expansion and contraction in normal man. Hypertension. 1979;1:583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinberger MH. Hypertension in African Americans: the role of sodium chloride and extracellular fluid volume. Seminars in Nephrology. 1996;16:110–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richardson SI, Freedman BI, Ellison DH and Rodriguez CJ. Salt sensitivity: a review with a focus on non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension : JASH. 2013;7:170–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pratt JH, Rebhun JF, Zhou L, Ambrosius WT, Newman SA, Gomez-Sanchez CE and Mayes DF. Levels of mineralocorticoids in whites and blacks. Hypertension. 1999;34:315–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bress A, Han J, Patel SR, Desai AA, Mansour I, Groo V, Progar K, Shah E, Stamos TD, Wing C, Garcia JGN, Kittles R and Cavallari LH. Association of aldosterone synthase polymorphism (CYP11B2 −344T>C) and genetic ancestry with atrial fibrillation and serum aldosterone in African Americans with heart failure. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71268–e71268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morris AA, Nayak A, Ko Y-A, D’Souza M, Felker GM, Redfield MM, Tang WHW, Testani JM and Butler J. Racial Differences in Diuretic Efficiency, Plasma Renin, and Rehospitalization in Subjects with Acute Heart Failure Circulation: Heart Failure. 2020;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell B and Franco J. HOLC “REDLINING” Maps: The persistent structure of segregation and economic inequality. Washington DC: National Community Reinvestment Coalition; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, Chambless L, Massing M, Nieto FJ, Sorlie P, Szklo M, Tyroler HA and Watson RL. Neighborhood of Residence and Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akwo EA, Kabagambe EK, Harrell FE, Blot WJ, Bachmann JM, Wang TJ, Gupta DK and Lipworth L. Neighborhood Deprivation Predicts Heart Failure Risk in a Low-Income Population of Blacks and Whites in the Southeastern United States. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2018;11:e004052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair IV, Cohen MS, Cruz-Flores S, Davey-Smith G, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Lauer MS, Lockwood DW, Rosal M and Yancy CW. Social Determinants of Risk and Outcomes for Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2015;132:873–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris AA, McAllister P, Grant A, Geng S, Kelli HM, Kalogeropoulos A, Quyyumi A and Butler J. Relation of Living in a Food Desert to Recurrent Hospitalizations in Patients With Heart Failure. American Journal of Cardiology. 2019;123:291–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Powell LM, Slater S, Chaloupka FJ and Harper D. Availability of physical activity-related facilities and neighborhood demographic and socioeconomic characteristics: a national study. American journal of public health. 2006;96:1676–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howell NA, Tu JV, Moineddin R, Chu A and Booth GL. Association Between Neighborhood Walkability and Predicted 10-Year Cardiovascular Disease Risk: The CANHEART (Cardiovascular Health in Ambulatory Care Research Team) Cohort. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang K, Lombard J, Rundek T, Dong C, Gutierrez CM, Byrne MM, Toro M, Nardi MI, Kardys J, Yi L, Szapocznik J and Brown SC. Relationship of Neighborhood Greenness to Heart Disease in 249 405 US Medicare Beneficiaries. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010258–e010258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lovasi GS, Neckerman KM, Quinn JW, Weiss CC and Rundle A. Effect of individual or neighborhood disadvantage on the association between neighborhood walkability and body mass index. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:279–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A and Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lo AX, Donnelly JP, Durant RW, Collins SP, Levitan EB, Storrow AB and Bittner V. A National Study of U.S. Emergency Departments: Racial Disparities in Hospitalizations for Heart Failure. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018;55:S31–S39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eberly LA, Richterman A, Beckett AG, Wispelwey B, Marsh RH, Cleveland Manchanda EC, Chang CY, Glynn RJ, Brooks KC, Boxer R, Kakoza R, Goldsmith J, Loscalzo J, Morse M and Lewis EF. Identification of Racial Inequities in Access to Specialized Inpatient Heart Failure Care at an Academic Medical Center. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2019;12:e006214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Breathett K, Liu WG, Allen LA, Daugherty SL, Blair IV, Jones J, Grunwald GK, Moss M, Kiser TH, Burnham E, Vandivier RW, Clark BJ, Lewis EF, Mazimba S, Battaglia C, Ho PM and Peterson PN. African Americans Are Less Likely to Receive Care by a Cardiologist During an Intensive Care Unit Admission for Heart Failure. JACC: Heart Failure. 2018;6:413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Breathett K, Yee E, Pool N, Hebdon M, Crist Janice D, Knapp S, Larsen A, Solola S, Luy L, Herrera-Theut K, Zabala L, Stone J, McEwen Marylyn M, Calhoun E and Sweitzer Nancy K. Does Race Influence Decision Making for Advanced Heart Failure Therapies? Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8:e013592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, Kerner JF, Sistrunk S, Gersh BJ, Dubé R, Taleghani CK, Burke JE, Williams S, Eisenberg JM, Ayers W and Escarce JJ. The Effect of Race and Sex on Physicians' Recommendations for Cardiac Catheterization. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:618–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI and Banaji MR. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007;22:1231–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA, Williamson JD and Wright JT. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;71:e127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WaC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJV, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WHW, Tsai EJ and Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brewster LM. Underuse of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate for heart failure in patients of African ancestry: a cross-European survey. ESC Heart Failure. 2019;6:487–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giblin EM, Adams KF Jr., Hill L, Fonarow GC, Williams FB, Sharma PP, Albert NM, Butler J, DeVore AD, Duffy CI, Hernandez AF, McCague K, Spertus JA, Thomas L and Patterson JH. Comparison of Hydralazine/Nitrate and Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitor Use Among Black Versus Nonblack Americans With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction (from CHAMP-HF). American Journal of Cardiology. 2019;124:1900–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khazanie P, Liang L, Curtis LH, Butler J, Eapen ZJ, Heidenreich PA, Bhatt DL, Peterson ED, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC and Hernandez AF. Clinical Effectiveness of Hydralazine–Isosorbide Dinitrate Therapy in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction: Findings From the Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure Registry. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2016; 9:e002444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, Carson P, D’Agostino R, Ferdinand K, Taylor M, Adams K, Sabolinski M, Worcel M and Cohn JN. Combination of Isosorbide Dinitrate and Hydralazine in Blacks with Heart Failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:2049–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Callier SL, Cunningham BA, Powell J, McDonald MA and Royal CDM. Cardiologists' Perspectives on Race-Based Drug Labels and Prescribing Within the Context of Treating Heart Failure. Health equity. 2019;3:246–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McNamara DM, Taylor AL, Tam SW, Worcel M, Yancy CW, Hanley-Yanez K, Cohn JN and Feldman AM. G-Protein Beta-3 Subunit Genotype Predicts Enhanced Benefit of Fixed-Dose Isosorbide Dinitrate and Hydralazine: Results of A-HeFT. JACC: Heart Failure. 2014;2:551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McNamara DM, Tam SW, Sabolinski ML, Tobelmann P, Janosko K, Venkitachalam L, Ofili E, Yancy C, Feldman AM, Ghali JK, Taylor AL, Cohn JN and Worcel M. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3) polymorphisms in African Americans with heart failure: results from the A-HeFT trial. Journal of cardiac failure. 2009;15:191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McNamara DM, Tam SW, Sabolinski ML, Tobelmann P, Janosko K, Taylor AL, Cohn JN, Feldman AM and Worcel M. Aldosterone synthase promoter polymorphism predicts outcome in African Americans with heart failure: results from the A-HeFT Trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;48:1277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, DeVore AD, Sharma PP, Duffy CI, Hill CL, McCague K, Mi X, Patterson JH, Spertus JA, Thomas L, Williams FB, Hernandez AF and Fonarow GC. Medical Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: The CHAMP-HF Registry. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;72:351–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Greene SJ, DeVore AD, Sheng S, Fonarow GC, Butler J, Califf RM, Hernandez AF, Matsouaka RA, Samman Tahhan A, Thomas KL, Vaduganathan M, Yancy CW, Peterson ED, O’Connor CM and Mentz RJ. Representativeness of a Heart Failure Trial by Race and Sex: Results From ASCEND-HF and GWTG-HF. JACC: Heart Failure. 2019;7:980–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, DeVore AD, Sharma PP, Vaduganathan M, Albert NM, Duffy CI, Hill CL, McCague K, Patterson JH, Spertus JA, Thomas L, Williams FB, Hernandez AF and Butler J. Titration of Medical Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73:2365–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McCoy RG, Dykhoff HJ, Sangaralingham L, Ross JS, Karaca-Mandic P, Montori VM and Shah ND. Adoption of New Glucose-Lowering Medications in the U.S.—The Case of SGLT2 Inhibitors: Nationwide Cohort Study. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics. 2019;21:702–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Colvin M, Smith JM, Hadley N, Skeans MA, Uccellini K, Lehman R, Robinson AM, Israni AK, Snyder JJ and Kasiske BL. OPTN/SRTR 2017 Annual Data Report: Heart. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2019;19 Suppl 2:323–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Breathett K, Allen LA, Helmkamp L, Colborn K, Daugherty SL, Blair IV, Jones J, Khazanie P, Mazimba S and McEwen M. Temporal Trends in Contemporary Use of Ventricular Assist Devices by Race and Ethnicity. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2018;11:e005008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tahhan AS, Vaduganathan M, Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, Fiuzat M, Jessup M, Lindenfeld J, O’Connor CM and Butler J. Enrollment of Older Patients, Women, and Racial and Ethnic Minorities in Contemporary Heart Failure Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review. JAMA cardiology. 2018;3:1011–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Simon MS, Du W, Flaherty L, Philip PA, Lorusso P, Miree C, Smith D and Brown DR. Factors Associated With Breast Cancer Clinical Trials Participation and Enrollment at a Large Academic Medical Center. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:2046–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DeJong C, Kazi DS, Dudley RA, Chen R and Tseng C-W. Assessment of National Coverage and Out-of-Pocket Costs for Sacubitril/Valsartan Under Medicare Part D. JAMA cardiology. 2019;4:828–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smith GH, Shore S, Allen LA, Markham DW, Mitchell AR, Moore M, Morris AA, Speight CD and Dickert NW. Discussing Out-of-Pocket Costs With Patients: Shared Decision Making for Sacubitril-Valsartan in Heart Failure. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8:e010635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Golden SD, McLeroy KR, Green LW, Earp JAL and Lieberman LD. Upending the Social Ecological Model to Guide Health Promotion Efforts Toward Policy and Environmental Change. Health Education & Behavior. 2015;42:8S–14S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kinnamon DD, Morales A, Bowen DJ, Burke W, Hershberger RE and Consortium* DCM. Toward Genetics-Driven Early Intervention in Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Design and Implementation of the DCM Precision Medicine Study. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2017;10:e001826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Freedman DA, Mattison-Faye A, Alia K, Guest MA and Hébert JR. Comparing farmers' market revenue trends before and after the implementation of a monetary incentive for recipients of food assistance. Preventing chronic disease. 2014;11:E87–E87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trapl ES, Smith S, Joshi K, Osborne A, Benko M, Matos AT and Bolen S. Dietary Impact of Produce Prescriptions for Patients With Hypertension. Preventing chronic disease. 2018;15:E138–E138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Greaney ML, Askew S, Foley P, Wallington SF and Bennett GG. Linking patients with community resources: use of a free YMCA membership among low-income black women. Translational behavioral medicine. 2017;7:341–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, Adam E, Duncan GJ, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Lindau ST, Whitaker RC and McDade TW. Neighborhoods, Obesity, and Diabetes — A Randomized Social Experiment. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:1509–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Committee on the Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures for Electronic Health Records; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Institute of Medicine Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015. January 8 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK268995/ doi: 10.17226/18951. Accessed April 21, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chan WV, Pearson TA, Bennett GC, Cushman WC, Gaziano TA, Gorman PN, Handler J, Krumholz HM, Kushner RF, Mackenzie TD, Sacco RL, Smith SC, Stevens VJ, Wells BL, Castillo G, Heil SKR, Stephens J and Vann JCJ. ACC/AHA Special Report: Clinical Practice Guideline Implementation Strategies: A Summary of Systematic Reviews by the NHLBI Implementation Science Work Group: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e122–e137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alsan M, Garrick O and Graziani G. Does Diversity Matter for Health? Experimental Evidence from Oakland. American Economic Review. 2019;109:4071–4111. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, Hernandez MH, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K and Bylund CL. The Effects of Race and Racial Concordance on Patient-Physician Communication: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2018;5:117–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, Blyler C, Muhammad E, Handler J, Brettler J, Rashid M, Hsu B, Foxx-Drew D, Moy N, Reid AE and Elashoff RM. A Cluster-Randomized Trial of Blood-Pressure Reduction in Black Barbershops. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378:1291–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Artiga S, Orgera K and Damico A. Changes in Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity since the ACA, 2010-2018. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/view/footnotes/ 2020. Accessed April 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Breathett K, Allen LA, Helmkamp L, Colborn K, Daugherty SL, Khazanie P, Lindrooth R and Peterson PN. The Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion correlated with increased heart transplant listings in African-Americans but not Hispanics or Caucasians. JACC: Heart Failure. 2017;5:136–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Breathett KK, Knapp SM, Wightman P, Desai A, Mazimba S, Calhoun E and Sweitzer NK. Is the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion Linked to Change in Rate of Ventricular Assist Device Implantation for Blacks and Whites? Circulation: Heart Failure. 2020;13:e006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Psotka MA, Fonarow GC, Allen LA, Joynt Maddox KE, Fiuzat M, Heidenreich P, Hernandez AF, Konstam MA, Yancy CW and O'Connor CM. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program: Nationwide Perspectives and Recommendations: A JACC: Heart Failure Position Paper. JACC: Heart Failure. 2020;8:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hersh AM, Masoudi FA and Allen LA. Postdischarge environment following heart failure hospitalization: expanding the view of hospital readmission. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2:e000116–e000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, Masimore B, Liu F, Haak LL and Kington R. Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science (New York, NY). 2011;333:1015–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA, Meseroll RA, Perkins MJ, Hutchins BI, Davis AF, Lauer MS, Valantine HA, Anderson JM and Santangelo GM. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Science advances. 2019;5:eaaw7238–eaaw7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Carnethon MR, Kershaw KN and Kandula NR. Disparities Research, Disparities Researchers, and Health Equity. JAMA. 2020;323:211–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.