Abstract

Objectives

The control of the COVID-19 pandemic depends strongly on effective communication, which must be grounded on the population’s perceptions and knowledge. We aimed to analyse the doubts, concerns and fears expressed by the Portuguese population about COVID-19.

Methods

We performed a content analysis of 293 questions submitted to online, radio, newspaper and TV channel forums during the first month of the pandemic in Portugal.

Results

Most questions contained doubts (n = 230), especially on how to prevent person-to-person transmission (n = 40) and how to proceed in case of symptoms (n = 37). Concerns and fears were also very commonly expressed (n = 144), mostly about which persons could be considered vulnerable (n = 53) and how to prevent transmission during daily life or normal activities (n = 37).

Conclusion

As the pandemic evolved and suppression measures were put in place, doubts moved to concerns of vulnerability, quarantine and social isolation, and to doubts about transmission, transmission prevention, and on how to proceed in case of symptoms.

Practice implications

These results may inform future communication strategies for a more adequate response in the next phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as in future pandemics.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemics, Health communication, Health literacy

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic strongly challenged society capacity to handle emerging threats. The control of a highly contagious airborne disease, transmitted by respiratory droplets, relies on simple measures as reducing the number and proximity of contacts, strengthening respiratory and hands hygiene and the use of mask. These individual behaviours depend on the health literacy of the population and on their living and working conditions.

The Health Belief model posits that the adoption of a behaviour strongly depends on the population’s perceptions on how they may be susceptible to a problem and if it may cause serious consequences, on the existence of actions that can prevent it and the benefits of its prevention outweigh its costs or barriers [1]. This model has been widely applied in the analysis and management of infectious diseases and epidemics. Five decades ago it was useful to understand the low participation in tuberculosis screening programmes [2], and more recently it has been used to analyse the effects of a MERS-CoV information campaign [3], influenza A high incidence rates among adolescents [4], or the dimensions that should be strengthened regarding dengue prevention and control strategies [5]. It has also been used in the case of this pandemic, to study the association of awareness and knowledge with behavioural change to prevent COVID-19 [6] and, more specifically, the dimensions associated with the use of contact tracing applications [7]. Thus, public perceptions about the disease and its health consequences, about the risk of transmission, and about how effectively they can prevent it are essential to individually control the infection transmission and its dissemination within the population locally and globally.

Comprehensive communication and community engagement strategies were recommended since the beginning of the pandemic. [8,9] These strategies would inform the general public about the disease, its transmission and how to control it at the individual and populational levels, potentially preventing “infodemics” (i.e., a situation when the excessive quantity of information hinders an adequate response of the person), reducing the impact of rumours and misunderstandings, and allowing the population to trust in scientifically sound advice to respond to the pandemic [10,11]. United Nations agencies have been working with national governments to fight misinformation, create awareness and inform about COVID-19 and what measures can effectively reduce its transmission [12]. In the Democratic Republic of Congo the government has engaged the community to report via social networks and SMS what rumours were circulating and where, and communication strategies were designed to respond to them [13]. Messages were channelled through social media, TV and mostly using radio, as it is more likely to reach the whole country. They organized workshops aimed at journalists to improve their capacity of recognizing fake news and prevent misinformation. A hotline was created and most calls requested general information about COVID-19.

The effectiveness of communication strategies depends on the assessment of the initial knowledge and perceptions of the population, so that they can answer to its gaps, especially those gaps that may hinder control measures [1,14]. Their progress must be tracked by observing if behaviour change has been achieved, which informs the need and how to redefine these strategies [15].

Previous studies have assessed the knowledge of the population about COVID-19 in the US and in the UK [16,17] and of the population and healthcare workers in Asian countries [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. Though, to the best of our knowledge, the current literature lacks data in the European setting and does not provide evidence on the main doubts of the population, their concerns or fears about COVID-19. This evidence can provide the much-needed assessment of the knowledge gaps and of the populations’ perceptions towards the infection, which influence behaviour change. It can also contribute to the monitoring and evaluation of national communication strategies and feed future ones. Thus, this study aims to fill this gap by analysing the doubts, concerns and fears expressed on the questions posed by the general population in public forums over the first month of the pandemic in Portugal.

2. Methods

Two days after the first COVID-19 case in Portugal (March 2nd 2020) the Institute of Public Health of the Porto University (ISPUP) launched an online Forum to answer to the questions of the Portuguese population regarding COVID-19, disseminated in social media. Two weeks after its launch the researchers from the ISPUP were invited to respond to questions posed in real time at a forum from one of the biggest national newspapers (Público), as well as at forums hosted by a national radio (Rádio Renascença) and a television channel (Porto Canal) based on the Northern region of Portugal. These were public, question-and-answer (Q&A) forums where answers were rarely followed by a second question, and answers to previous questions could be consulted by other users. Between March 4th and April 3rd 2020, 293 questions were submitted in these forums.

This qualitative study focused on the content analysis of those questions carried out according to the protocol established by Stemler [23] and using the software NVivo 12 (QSR International, USA, 2018). A trial coding was independently conducted by the first and second authors on a set of 100 questions using an initial codebook of a priori categories developed by the researchers with a background on medical and social sciences. Disagreements in abstractions were discussed until reaching consensus, and a strong agreement was achieved. The remaining data were independently coded by the researchers using the improved set of categories. The final codebook encompasses the a priori categories and the emergent categories developed during the entire coding process. The categories were then grouped into the following analytical themes: (i) ‘concerns and fears’, which includes references to medical and technical concerns; preventive behaviours; rumours, fake news, contradictory information and search for credible sources of information; financial, social and psychological impact; future directions; and (ii) ‘doubts’, which contains references to population doubts regarding medical and technical issues; practical doubts about the virus’ transmission and hygiene; legal, social rights and social support. The findings are reported with verbatim quotes from the questions translated by the authors. The date of submission was used as an attribute for results comparison.

This study did not involve any intervention in human subjects. Only questions submitted to public forums were used, we did not reveal any username and we avoided using citations that could reveal the persons’ identities

3. Results

We analysed 293 questions submitted to the ISPUP Forum (43.0 %), to the Rádio Renascença COVID-19 Forum (30.7 %), to the Público newspaper forum (13.3 %), to the Ask Me Anything forum on Reddit hosted by the Rádio Renascença (9.9 %), and to the Porto Canal television channel (3.1 %).

Questions expressed more frequently doubts (n = 230), but a large number of them also expressed concerns and fears (n = 144) (Table 1 ). Concerns and fears were more frequently asked through the Institute’s, Público’s and Radio Renascença’s forums, while doubts were asked on the Reddit and Porto canal forums. Questions posed through Reddit were particularly different from the remaining platforms, with a higher focus on medical and technical doubts, as well as on the uncertainty about the future.

Table 1.

Codebook of issues presented in the questions about COVID-19 from Portuguese population (n = 293).

| Coded questions (n) | Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Doubts | 230 | |

| Medical and technical doubts | ||

| How to proceed in case of symptoms | 37 | “I have fever and cough, what should I do?” “I have flu-like symptoms like fever and cough, but I haven't been in contact with infected people or made any recent trip. Should I seek for help?” |

| About the virus, the disease, immunity | 29 | “In December 2019, I got a vaccine for seasonal flu and another for pneumonia. Do I have any immunity for this Coronavirus?” “Are there cases of people who have been cured and the virus has reoccurred?” |

| Signs and symptoms | 19 | “Which are the symptoms and how long it takes to develop the disease?” |

| Treatment, healing, case fatality | 18 | “When the infection is confirmed, what is the treatment?” |

| About transmission | 17 | “What is the evidence about the transmission in asymptomatic cases? Is there evidence of transmission without symptoms? (…)” “If we get the virus, how long does it take to transmit to others?” |

| Tests | 14 | “What is the sensitivity of the COVID-19 diagnostic test used in Portugal, in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients?" |

| How to proceed in case of traveling | 13 | “I have a family member who went to Italy for work, he returns tomorrow, and I would like to know what measures should I take (…) He has no symptoms, but he has high blood pressure and chronic bronchitis.” |

| Health systems response capacity | 8 | “What do you think about the government’s and health authorities’ actions in facing this situation? Do you think that Portugal is able to deal well with this virus and that the national health system will be able to endure the rising number of new cases?” |

| Interpreting technical terms and scientific data | 6 | “We are in the mitigation phase – what does it mean? How long this period can take?” |

| Vaccine | 4 | “(…) Are we going to have a new vaccine that everyone takes, and it will never be a problem again, or is it going to be a recurring illness just like the flu?” |

| How to proceed in case of other disease | 3 | “I am a 40-year-old man with a transplanted kidney and taking immunosuppressants. What specific care and procedures should I have?” |

| Practical doubts | ||

| About transmission between persons | 40 | “How do I know, after this crisis, when can I go out without fear and feeling safe?” “What precautions should we take when a colleague is from an affected area [with community transmission]?” |

| About transmission through objects, food, environment and animals | 28 | “Do I need to disinfect my grocery? How long can the virus remain in products?” “I would like to know if there is, at the moment, any indication about the contagion between animals and humans?” |

| About the use of equipment as masks and gloves, and hand hygiene | 18 | “Is 96 % alcohol effective in killing the virus?” “I have a mask that I wear when I go to my parents' house in order to protect them (I think the exposure is easy in my professional activity), but I don't know if it [mask] can be used more than once. How many times can a mask be used?” |

| Environmental hygiene and disinfection | 18 | “Is it important to disinfect the cell phone? How can I do it? Should I avoid contact with my face? (…)” |

| Legal and social rights, social support | 27 | “I work in a forest cleaning company. I already had three pneumothoraxes, I intended to stay at home, but the company says no. Am I in a risk group? Am I really obliged to go to work?” “The elderly care facility has been closed. Will I receive support for taking care of the elderly at home?” |

| Concerns and Fears | 144 | |

| Medical and technical concerns | ||

| About vulnerable persons | 53 | “I have a family member in an elderly care facility with no COVID-19 positive cases. Should I bring them home?” “My wife is pregnant, and I am from the Felgueiras municipality [where the outbreak started in Portugal]. Should she take any measures [to prevent the disease]?” |

| About symptoms | 17 | “I have a bit of a cough, a stuffy nose and some headaches. I don't have fever. I don't know if it's a flu or a cold or COVID-19. What is the most likely to be? I am in a house where there is a person who was on a plane with another person who is suspected of COVI-19 positive”. |

| About protecting others | 13 | “As a general practitioner, married and mother of 2 children under the age of 5, who tomorrow will work for the frontline of combat, how can I protect my nuclear family? What steps should I take?” |

| About the transmission | 6 | “Is it not inconsistent with closing libraries and suspending classes when the public transports, which are powerful transmission vehicles, continue to operate?” |

| Preventive behaviours | ||

| Daily and normal activities | 37 | “My housekeeper works at several houses, is it prudent to continue to come here?” “My husband works in a factory, and he has been going work every day. I know he is careful, but I am scared. We have an extra room at home. Is it better for us to sleep apart?” |

| Isolation requirements | 26 | “A school just closed after confirmation of COVID-19 in a parent. My children were there for two hours. Should all children in that school be in quarantine? If so, how many days?” |

| Behaviours during quarantine and social isolation | 21 | “In addition to washing our hands often and avoiding going out, only when strictly necessary, what other type of behaviour should we adopt?” “What precautions should we follow if we have someone infected at home, to prevent transmission to the remaining household?” |

| Financial, social and psychological impact | 8 | “Since quarantine is something new in our society, what emotional impact will it have on us and how can we combat the feeling of exclusion?” “Regarding the national economy, how would a possible national quarantine worsen the financial situation of the country, companies, families, etc… In future, will life return to "normal" or "the same" as usual?” |

| Uncertainties about the future | “(…) After these initial two or three months of containment measures like isolation and quarantine, what will be the plan to control the virus? (…)” | |

| Rumours, fake news, contradictory information and search for credible information | 5 | “There has been contradictory information from health authorities regarding the use of ibuprofen in case of contracting COVID-19 (…) How should we do in case of mild symptoms?” |

3.1. Doubts

Most of the population’s doubts were about medical and technical issues (n = 141). Doubts focused on how to proceed in case of symptoms (n = 37), such as what to do if some has a cough, headaches and other “flu-like symptoms”, who should be tested and where, should avoid going to work or quarantine. Doubts about the SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, and immunity were frequent (n = 29) (“Are there any studies about the risk of reinfection and its severity?”), and were followed by questions about its signs and symptoms (n = 19), as what other symptoms may be related to COVID-19 apart from fever, dry cough and shortness of breath. Treatment options, healing possibilities and the case fatality of disease were also asked (n = 18), namely questioning about the effectiveness of vitamin supplementation, the use of racetamol, ibuprofen or other anti-inflamatory drugs, or suggesting to test chloroquine or hydroxychoroquine in the population of a municipality under cordon sanitaire measures. The risk of transmission in “symptomatic and asymptomatic cases” (n = 17) was asked, a well as the availability and sensitivity of diagnostic tests (n = 14). People stated doubts about travelling (n = 13), asking for how to proceed in case of having “family members who return from endemic countries due to work commitments” as well as for some advice on what to do in case of booked holidays trips.

Practical doubts were also expressed (n = 92), most frequently about transmission between persons (n = 40) (“what is the evidence about the transmission by asymptomatic cases?”; “what are the measures and procedures I should follow in the case of having someone infected at home, to avoid the transmission to other cohabitants?”), and through objects, animals, food and environment (n = 28) especially concerning “recently bought grocery” and food, as well as shoes and clothing. People also mentioned doubts regarding the use and “re-use of gloves (washing them) and masks (with bleach or boiling water)”, the adequate disinfectant to use on hand hygiene (n = 18)), as well as regarding hygiene and disinfection of surfaces and objects, such as “cell phones, bathrooms, handrails and door handles” (n = 18). Many questions expressed doubts regarding legal and social rights, as well as social support (n = 27) such as the following quotes show: “I work in a forest cleaning company (…) my intention was to stay at home, but the company says no (…) am I really obliged to go to work?”; “The elderly care facility has been closed. Do I receive [any financial] support by taking care of the elderly at home?”.

3.2. Concerns and fears

Population expressed mainly medical and technical concerns (n = 78) and worries about preventive behaviours (n = 72), followed by concerns about the financial and social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 8), such as the “emotional impact that the quarantine will have on people” and “ways to combat the feeling of exclusion”, uncertainties of the future (n = 7), such as the “plan to control the spread the virus after the initial months of quarantine”, and concerns raised by rumours, fake news, contradictory information (n = 5), specially “the news on the effects of ibuprofen”.

People were mainly concerned with the effect of the disease on vulnerable persons (n = 53), asking the risks for several pathologies, questioning if they are part of high risk groups and what to do to control the risks, as well as on how to protect others from themselves when they get infected (n = 13). Questions also reflected fears of being infected while having mild symptoms similar to those of COVID-19, such as “a little cough, a stuffy nose and some headaches” (n = 17), and about being at risk of being infected through cohabitants who flew, by the contact with symptomatic persons who weren’t tested, or in public transportation (n = 6). Concerns about how to prevent the transmission during daily life or normal activities (n = 37), “like working at multiple places” and “using public transports”, and about the correct behaviours to adopt during quarantine or social isolation (n = 21), like the need to “always wash the hands” and the possible danger of going out to “get some fresh air” were very common. In addition, fears and concerns regarding who should be on social isolation and when (n = 26) (“Should individuals who were in contact with other individuals that were in a place where a COVID-19 case was identified isolate?”) were also frequently mentioned.

3.3. Doubts, concerns and fears over time

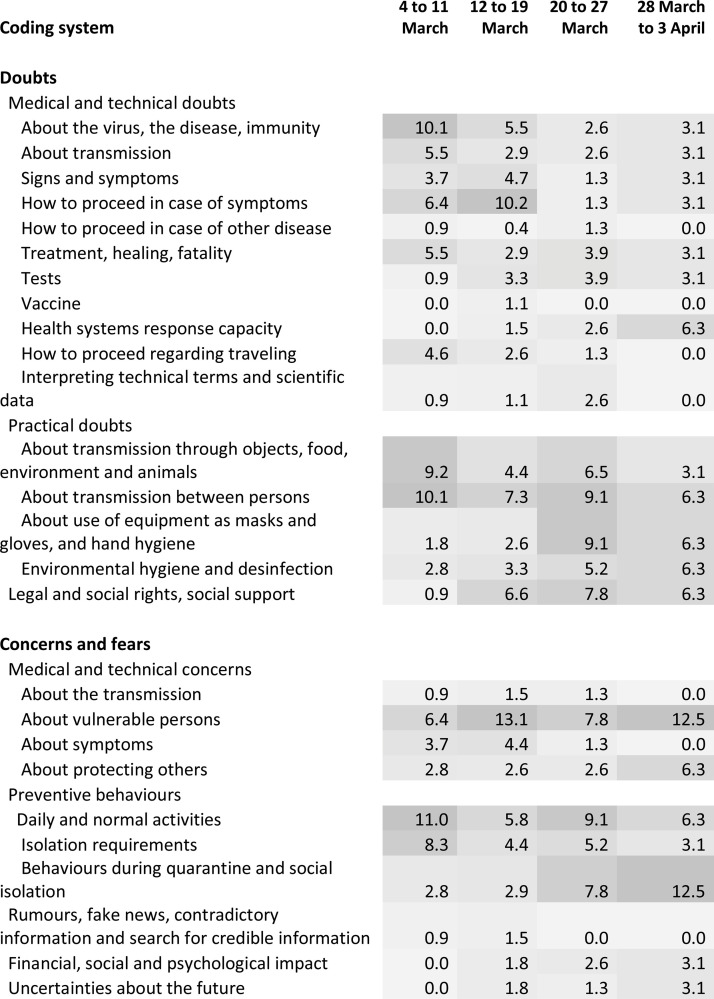

Through the temporal analysis, we verified that the content of questions changed during this one-month period (Fig. 1 ). In the first time period, from the 4th to 11th of March, questions expressed mostly population’s concerns on how to prevent transmission while continuing daily life or normal activities, who should be on home isolation, as well as people’s doubts about the disease and its way of transmission.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of categories coded by time period: the figure shows the frequency each category was coded in each period (in clear shade the category with lowest frequency, in dark shade with the highest).

From the 12th to 19th of March, population’s concerns about which persons were vulnerable and how to protect others increased in relative frequency, as well as people’s worries about the procedures in case of having symptoms.

From the March 20th to 27th, questions submitted to the forums reflected concerns about how to continue daily life or normal activities while keeping the risk of transmission low, and about quarantine or social isolation. Doubts regarding transmission and about the use of masks, gloves, hand and environment hygiene products increased compared to the previous time periods. Though not the most reported ones, questions about the legal and social rights and social support reached a peak in this period.

From the 28th of March to the 3rd of April, questions from the Portuguese population expressed a raise in fears about the susceptibility of the most vulnerable persons, as elderly, pregnant women and people with chronic conditions, to get infected, and concerns on how to protect them. Moreover, people showed concerns about quarantine or social isolation and on how to continue their normal daily activities, such as working. Doubts about the health systems response capacity emerged, and doubts about transmission between persons, use of masks, gloves, hand and environment hygiene products remained frequent. Though the relative frequency of report was low, questions expressing population’s concerns about the financial, social and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions implemented, and of uncertainty about the future peaked during this period.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

The content analysis of 293 questions posed in COVID-19 web, newspaper, radio and television forums enlightened the main doubts, concerns and fears from the general Portuguese population from the 4th March until 3rd April. Doubts were most commonly about the virus and disease, its transmission, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment and fatality, and about how to proceed for preventing transmission and in case of having symptoms. Fears and concerns were mostly regarding which persons could be considered vulnerable, how to prevent transmission during daily life or normal activities, what quarantine or social isolation means, and who should be on social isolation.

The content of the questions varied according to the period of contact of the population to the pandemic in Portugal. In the days where first cases were diagnosed, until the 11th March, [24] population revealed doubts about the virus, the disease and its transmission, as well as about requirements to be in social isolation. With the exponential rise of the number of COVID-19 positive cases, questions about who would be considered part of high-risk groups, how the transmission occurred between persons, and how to proceed in case of symptoms started emerging within the general public. Simultaneously, the Portuguese government decision for closing the schools, on the 16th March, and for implementing movement restrictions, in the 22nd March, under an emergency state declaration raised concerns about quarantine and social isolation, as well as related to the ‘normal’ daily activities. [24] In addition, this new reality raised people’s doubts about the use of masks, gloves and hand hygiene products, and about the possibility of transmission through objects, food, animals and environment as well as about the legal and social rights and support to the families. Some newspaper articles showed that in the beginning of the pandemic questions posed to the national health info line were overall similar to those identified in this study: people had doubts regarding travelling or about the risks of having dinner at Chinese restaurants or receiving packages from China [25]. A month later, a platform answering to “Can I” doubts received questions related to basic daily life gestures as cleaning and managing the garbage, visiting the family or having access to social support [26].

If the evolution of the questions’ contents was easily explained by the evolution of the pandemic and the timing of measures’ implementation, the large number of questions actively posed about simple issues as disease transmission and transmission prevention were not expected. Although this study does not merely aim at drawing conclusions on population knowledge about COVID-19 but about its doubts, concerns and fears, these results seem to contrast with evidence from recent studies in the UK and US [16,17] and in Asian countries [[18], [19], [20]], which showed an overall well-informed sample about issues similar to those asked by the Portuguese population.

Several hypotheses could be raised to explain these differences. First, posing questions may not indicate a lack of knowledge, but the simple need to confirm perceptions or ideas, or to clarify rumours or fake news. Indeed, fake news and rumours disseminated in the social media, ‘speed science’ creating and publicizing non-peer reviewed articles, or even regular news report questioning measures taken, may create doubts and concerns on the population. [[27], [28], [29], [30]] Also, anxiety created by physical distancing, quarantine and economic constraints may increase the population’s need to confirm information or to verify what are the “experts’” opinions, and thus using these platforms to do so.

Second, the communication strategy may not have been effective in informing and ensuring the population. In Portugal, official communication about COVID-19 is centralized by the Health Ministry, specifically in the General-Directorate of Health. Materials as videos and infographics have been produced and published in social media since mid-February. A microsite, later updated on an independent website, was created and compiled videos, infographics, manuals and booklets, which were also made available in the social media (https://covid19.min-saude.pt/). An official website explaining the measures implemented by the government to control the pandemic (e.g.; movement restrictions), legal and social rights and support was published in the 19th of March (https://covid19estamoson.gov.pt/). Despite the efforts, these communication strategies could not have reached the entire population, especially groups with no access to the internet or lower literacy levels. These strategies could also have failed at capturing the populations’ attention and effectively passing the messages.

Third, individuals may have had contact with COVID-19-related information, but the low trust in the governmental institutions [31] may have limited trust in the information conveyed by them.

We believe that the doubts, concerns and fears identified in this study do overlap with those from populations from other high-income countries. Indeed, most questions were already or had become answered in frequently answered questions or Q&A webpages from Public Health organizations, as the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and its US counterpart and the UK governmental website dedicated to COVID-19, which indicates that the questions posed to these organizations might have coincided with those posed in our forums. We also believe that the evolution on the contents of questions must have been similar, as it is expected that in the first contact of a population with an unknown risk that is more incident in other countries raise questions about the disease and its way of transmission, who is at risk and the risk of traveling; as the pandemic evolves, it is understandable that the population questions whether they should continue its normal daily activities or quarantine, the susceptibility of the most vulnerable persons, how to prevent the transmission and the capacity of the health system to answer to the rising incidence; as lockdown measures are put in place for several weeks questions regarding the financial, social and psychological impact of the pandemic, and of uncertainty about the future emerge.

From the Health Belief model perspective, these findings show that though the level of knowledge of these participants could hinder their capacity to adopt adequate protective behaviours, their perceptions increase the likelihood to adhere to them. Indeed, the questions posed, especially those coded as medical and technical doubts show that these persons perceived COVID-19 as an important threat as they wondered if themselves or their loved ones could be susceptible to the infection (perceived susceptibility to disease) and what could be its consequences (perceived severity of disease). Questions about practical preventive behaviours reflected that these persons potentially perceived its benefits and wanted to improve their self-efficacy. Moreover, questions posed into these forums also demonstrated that some people perceived several barriers to the effective prevention of COVID-19, as incapability of working from home, being a health professional, not having access to test, or the non-response of the national health info line, but also a willingness to know how to overcome them (which can be interpreted as the search for cues). These questions also show that concerns and fears about the disease, reflected the perception of threat, which tends to have an important role in the perception of benefits of behaviour change and in mobilizing the population into behaviours’ adoption [2].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analysing the content of questions on COVID-19 issued by community members. To know the main concerns and doubts of the general public is crucial to designing and implementing effective communication strategies aimed to stop the spread of the disease. However, some limitations should be taken into account when considering these results. First, this analysis did not evaluate the population knowledge on COVID-19 related issues. Though, our aim was to assess the concerns, fears and doubts that moved individuals to ask questions in public forums. Second, the questions posed could have been influenced by those previously answered, reducing the number of repeated questions and, thus, the weight of that content in our analysis. We believe this limitation was minimized by the analysis of questions from different forums, where these questions were less likely to have been previously answered. Also, as we can see from our results, many questions were repeatedly posed yet using different formulations, showing that many persons probably prefer pose their “own” question. Third, we cannot infer these results to the whole population, as (i) data about gender, age, or educational background was lacking, (ii) individuals who had access to these platforms may not represent individuals from lowest socioeconomic groups, which may have lower access to the internet, computer, or less capacity to pay a call to the radio or television station, may have lower literacy and are probably less empowered to make questions, (iii) nor from highest socioeconomic groups, as these may be more capable to find and select information from trustful sources and understand it. Yet, we were still able to analyse these issues through questions posted in diverse platforms commonly used by most of the Portuguese population, including a television channel based in north of Portugal, the region most affected by the epidemic in its first weeks.

4.2. Conclusion

Doubts, concerns and fears by the population expressed in questions submitted to public forums focused mainly on common issues as COVID-19 transmission and its prevention, risk-groups and how to protect them, the risk of maintaining ‘normal’ daily life and whether and how to be in quarantine or social isolation. The emergence of these issues followed the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and overlapped with implemented control measures, despite the information tools created by official health institutions.

4.3. Practice implications

The promotion of adequate behaviours among the population, especially after the return to this “new” normal must be supported by a robust health communication strategy. As the population still have doubts independently of the information displayed in institutional websites, other channels must be considered to inform the population. Considering the current phase of the pandemic and the results of this study, communication strategies must convey clear informations about COVID-19 prevention and management and about access to health and social support services. This knowledge will be essential to improve the ability of individuals to respond to this crisis and the – much needed - trust in health organizations.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

TL and HB contributed for conceptualization of the study. TL and MA contributed for methodology definition, formal analysis, validation and writing of the original draft. All authors reviewed and edited the several versions of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cragg L., Davies M., Macdowall W. second edi. McGraw Hill; Berkshire, England: 2013. Health Promotion Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum A., Newman S., Weinman J., West R., McManus C. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1997. Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsulaiman S., Rentner T. The health belief model and preventive measures: a study of the ministry of health campaign on coronavirus in Saudi Arabia. J. Int. Cris. Risk Commun. Res. 2018;1:27–56. doi: 10.30658/jicrcr.1.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Najimi A., Golshiri P. Knowledge, beliefs and preventive behaviors regarding Influenza A in students: A test of the health belief model. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2013;2:23. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.112699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siddiqui T.R., Ghazal S., Bibi S., Ahmed W., Sajjad S.F. Use of the health belief model for the assessment of public knowledge and household preventive practices in Karachi, Pakistan, a dengue-endemic city. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jose R., Narendran M., Bindu A., Beevi N., M. L, Benny P.V. Public perception and preparedness for the pandemic COVID 19: a Health Belief Model approach. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Heal. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walrave M., Waeterloos C., Ponnet K. Vol. 6. 2020. pp. 1–10. (Adoption of a Contact Tracing App for Containing COVID-19 : A Health Belief Model Approach Corresponding Author). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . 2020. Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Increased Transmission Globally – Fifth Update What Is New in This Update, Solna. [Google Scholar]

- 9.IFRC, UNICEF, World Health Organization . 2020. RCCE Action Plan Guidance - COVID-19 Preparedness & Response, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . 2020. Risk Communication and Community Engagement Readiness and Response to Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez-mon M.A., Llavero-valero M., Rodrigo S., Alvarez-mon M.A. Vol. 21. 2019. pp. 1–11. (Areas of Interest and Stigmatic Attitudes of the General Public in Five Relevant Medical Conditions : Thematic and Quantitative Analysis Using Twitter Corresponding Author). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations . 2020. United Nations Comprehensive Response to Saving Lives, Protecting Societies Recovering Better, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gavi . 2020. How Creative Communication Strategies Are Helping Fight COVID-19 Misinformation in DRC.https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/how-creative-communication-strategies-helping-fight-covid-19-misinformation-drc [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO . World Heal. Organ.; 2017. WHO Strategic Communications Framework; p. 56. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/communication-framework.pdf?ua=1#:∼:text=For purposes of WHO’s Strategic,key audiences” are used interchangeably.&text=The Framework is organized according,to ensure WHO communications are%3A&text=accessible • actionable •. [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Sullivan G.A., Yonkler J.A., Morgan W., Merritt A. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Cener for Communication Programs; Baltimore: 2003. A Field Guide to Designing a Health Communication Strategy A Field Guide to Designing a Health Communication Strategy. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geldsetzer P. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional online survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020:2–5. doi: 10.7326/M20-0912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fridman I., Lucas N., Henke D., Zigler C.K. Public knowledge about COVID-19 and trust in sources of information: what helps people to stay informed and adhere to recommended social distancing? JMIR Public Heal. Surveill. 2020;6:1–17. doi: 10.2196/22060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao B., Kong F., Aung M.N., Yuasa M., Nam E.W. Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) knowledge, precaution practice, and associated depression symptoms among university students in Korea, China, and Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:1–17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azlan A.A., Hamzah M.R., Sern T.J., Ayub S.H., Mohamad E. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2020;15:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Hanawi M.K., Angawi K., Alshareef N., Qattan A.M.N., Helmy H.Z., Abudawood Y., Alqurashi M., Kattan W.M., Kadasah N.A., Chirwa G.C., Alsharqi O. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19 among the public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health Serv. Syst. Res. 2020;8:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saqlain M., Munir M.M., Rehman S.U., Gulzar A., Naz S., Ahmed Z., Tahir A.H., Mashhood M. Knowledge, attitude, practice and perceived barriers among healthcare workers regarding COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;105:419–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong B., Luo W., Li H., Zhang Q., Liu X., Li W., Li Y. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak : a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16 doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stemler S.E. An overview of content analysis. Pract. Assessment, Res. Eval. 2001;7 [Google Scholar]

- 24.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and European Food Safety Authority . 2020. COVID-19 Dashboard.https://qap.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/COVID-19.html (Accessed June 3, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neves S. 2020. Desnecessárias Ou Compreensíveis: a Que Tipo De Dúvidas Respondem Os Profissionais Da Linha SNS24?, Público.https://www.publico.pt/2020/03/16/sociedade/noticia/desnecessarias-compreensiveis-tipo-duvidas-respondem-profissionais-linha-sns24-1907854 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Correia P. 2020. Não Sabe O Que Pode Ou Não Fazer Em Tempo De Covid-19? O posso.pT Responde, TSF.https://www.tsf.pt/portugal/sociedade/nao-sabe-o-que-pode-ou-nao-fazer-em-tempo-de-covid-19-o-possopt-responde-12063729.html [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma M., Scarr S., Reuters T., Kelland K. 2020. Coronavirus and the Risks of’ Speed Science’, 24 March 2020.https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/speed-science-coronavirus-covid19-research-academic [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerwin L.E. The challenge of providing the public with actionable information during a pandemic. J. Law, Med. Ethics. Fall. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization . 2020. Munich Security Conference Speech, 15th Febr. 2020.https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/munich-security-conference (Accessed April 10, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyilasy G. Fake news : when the dark side of persuasion takes over. Int. J. Advert. Mark. Child. 2019;38:336–342. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2019.1586210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.European Commission . European Comission; Brussels: 2019. Public Opinion in the European Union. [Google Scholar]