Abstract

The Colorado Mentoring Training program (CO-Mentor) was developed at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in 2010, supported by the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute. CO-Mentor represents a different paradigm in mentorship training by focusing equally on the development of mentees, who are valued as essential to institutional capacity for effective mentorship. The training model is unique among Clinical and Translational Science Award sites in that it engages mentors and mentees in an established relationship. Dyads participate in 4 day-long sessions I scheduled throughout the academic year. Each session features workshops that combine didactic and experiential components. The latter provide structured opportunities to develop mentorship-related skills, including self-knowledge and goal setting, communication skills (including negotiation), “managing up,” and the purposeful development of a mentorship support network. Mentors and mentees in 3 recent cohorts reported significant growth in confidence with respect to all mentorship-related skills assessed using a pre–post evaluation survey (P = .001). Mentors reported the most growth in relation to networking to engage social and professional support to realize goals as well as sharing insights regarding paths to success. Mentees reported the most growth with respect to connecting with potential/future mentors, knowing characteristics to look for in current/future mentors, and managing the work environment (e.g., prioritizing work most fruitful to advancing research/career objectives). CO-Mentor represents a novel approach to enhancing mentorship capacity by investing equally in the development of salient skills among mentees and mentors and in the mentorship relationship as an essential resource for professional development, persistence, and scholarly achievement.

Mentorship training programs are critical to increase the absolute number, competencies, and diversity of clinical and translational researchers.1–5 Mentorship can function as a dynamic resource within an academic research setting, facilitating scholarly pursuit and productivity, social integration into an institution and specialty/discipline, and overall career satisfaction.6 The transmission of knowledge, expertise, and resources from mentors to mentees is fundamentally important to professional development and the efficient achievement of career milestones.7–9

The Mentorship Training Gap

Mentorship training programs tend to focus on preparing mentors for their roles, with mentees presumed to be the passive recipients of effective mentorship approaches.10 In our review of the literature on formal mentorship training programs at clinical and translational science award (CTSA) sites, we found only one program that featured mentees/junior faculty as an explicit focus of a comprehensive mentorship training initiative.11 The associated publications, however, focused solely on describing the training and preparation of mentors for their roles.12,13 Another CTSA site acknowledged the importance of examining the impact of formal mentorship training programs on both mentors and proteges. In contrast to the inclusive nature of the program evaluation, the description of the training program suggested that only mentors participated in the online course.14

In mentorship, as in any relationship, interpersonal dynamics and outcomes emerge synergistically from what both mentors and mentees bring to the relationship as well as the interplay of personality, communication styles, needs, and interests. The relative inattention given to the development of mentees in formal mentorship training programs contributes to ineffective communication, misaligned expectations, and missed opportunities to create mutually beneficial mentorship relationships. To respond to the dynamic nature of mentorship relationships and optimize the potential productivity of these relationships, mentees as well as mentors should receive formal training. Further, and equally important, providing mentees with formal mentorship training will strengthen the pipeline of future mentors.

The Colorado Mentoring Training Program

This understanding led to the development of the Colorado Mentoring Training program (CO-Mentor) at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, which seeks to address gaps in the development of skills that are pivotal to career success. CO-Mentor focuses on preparing the mentee as the leader, with self-knowledge and clarity of purpose; the mentor as the facilitator with advanced knowledge and resources that mentees can tap into for support; and the relationship between mentor and mentee as the primary resource. Here, we describe the CO-Mentor program model and present program outcomes based on the aggregated results of 3 recent cohorts. Given the paucity of training programs that focus on or include mentees, we give relatively more emphasis to evidence regarding the impact of the CO-Mentor program on mentee participants.

With support from the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CCTSI), CO-Mentor was developed in 2010 (by J.T.Z. and A.M.L., subsequently directed by G.L.A. and A.M.L.) as a 4-part training series that spans the academic year and engages mentor–mentee pairs, who are in an existing mentorship relationship, as participants. The program uses evidence-based strategies to teach the skills needed to garner and provide effective mentorship support. Specifically, the CO-Mentor program is designed to provide participants with structured opportunities to develop mentorship-related skills. These include goal setting, communication skills (including negotiation), “managing up”10 (i.e., proactively directing the relationship), and the purposeful development of a mentorship support network to ensure access to the variety of supports that should derive from effective mentorship. Throughout the program, we engage mentors and mentees in explicit discussions regarding each person’s expectations for the relationship.

Program directors and evaluators have adopted self-determination theory (SDT) as a salient theoretical perspective to help elucidate the pathways by which effective mentorship contributes to career success and persistence. SDT has 3 main components, each of which represents a domain that mentorship can directly influence: autonomy (sense of control and continuity achieved through intentional goal setting and purposeful action), competency (feelings of mastery over skills that are essential to one’s work and that are respected and valued in one’s profession), and relatedness (feelings of being respected among peers and supervisors).15 Chart 1 aligns the CO-Mentor program curriculum with key constructs of SDT.

Chart 1.

CO-Mentor Curriculum Scope and Sequence Aligned With Key Constructs of Self-Determination Theory

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prework/homework | |||

| Bring CV | 1. Communication skills practice 2. Peer meeting 3. Review revised CV with mentor |

1. Complete values clarification and goal setting worksheets 2. Draft personal narrative |

1. Bring letters of support 2. Craft personal mission statement 3. Create map of mentor network |

| Morning | |||

| CO-Mentor introduction and participant icebreaker |

Mentees: Creating your personal board of directors (competency and relatedness) Mentors: Giving effective feedback (competency and relatedness) |

Using your strengths to reach your goals (autonomy and competence) | Academic persistence and work–life balance (autonomy) |

| Career mapping: CV review (autonomy) | |||

| Afternoon | |||

| Communication skills for mentoring with case studies (relatedness) | Money mentoring with case studies: Negotiation to money mentoring (autonomy and competency) | Values clarification and goal setting (autonomy) | Networking skills (competency and relatedness) |

| Creating a personal narrative and career development plan (autonomy) | Effective letters of support with attention to gender differences (competence) | ||

| Mentor–mentee time | Mentor–mentee time | Mentor–mentee time | Mentor–mentee time |

Abbreviations: CO-Mentor, Colorado Mentoring Training program; CV, curriculum vitae.

Program recruitment

Initial recruitment cycles begin with email prompts to directors of training programs on campus and personal invitations to junior faculty in other CCTSI training programs. In addition, we solicit program referrals through the end-of-program evaluation survey, which consistently yields 30 or more names of individuals whom former participants anticipate might benefit from the program. Finally, invitations are extended to faculty at CCTSI-affiliated institutions, such as the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, Denver Health and Hospital Authority, National Jewish Health, and Kaiser Permanente Colorado. Several National Institutes of Health T32 and K12 institutional training grants have written CO-Mentor participation into program requirements, which renews the enrollment pool. Mentee participants are pivotal to recruitment; they tend to recruit their mentors and subsequently return as mentors to participate with their own mentees. Participants self-identify as mentees or mentors within the context of the participating dyad. We post program dates by mid-April and enrollment fills by the end of May. We ask enrollees to pledge to participate in all 4 sessions and to agree that, should they be unable to attend a session, they send a substitute mentor or mentee in their place for that program day. Initially, the program was limited to those with a faculty appointment. Subsequently, CO-Mentor accepted trainees, the majority of whom were within 2 years of transitioning to a faculty position. CCTSI covers the operating costs of the program; there are no fees for participants.

Program delivery

Our pedagogy relies on workshop-style sessions and case studies to support experiential learning and sustained engagement. We use academic products (e.g., curriculum vitae (CVs), letters of support, personal statements) as the basis for active learning projects, both during and outside of the workshops, to enhance the relevance and immediate utility of activities. Further, we use mentoring aids (e.g., career development plans, goal setting, personal mission statements, and mentor maps) to structure activities that can help a mentee clarify their own thinking and improve communication of those thoughts to a mentor. These products, which are developed and/or strengthened during the training, can enhance career development and support advancement in clinical and translational research.

Each session begins with participants debriefing their efforts to try a new skill introduced during the previous CO-Mentor session. Subsequently, we deliver 2 active learning workshops followed by a lunch break. Sessions conclude with 30 minutes of dedicated mentor–mentee time, guided by an exercise that is designed to stimulate conversation based on the day’s training. Overall, workshops involve mentor and mentee pairs participating together except for 1 half-day in which the pairs separate for a mentor program on giving feedback and for a mentee program on self-advocacy skills (“managing up” or building your own personal board of directors).

Program evaluation

The Evaluation Center, in the School of Education and Human Development at the University of Colorado Denver, has provided external evaluation services for the CCTSI and associated programs since the institute’s inception in 2008. The Evaluation Center carries out annual and longitudinal evaluation of CO-Mentor as one of the education, training, and career development programs of the CCTSI. Our annual evaluation uses a pre–post matched design to assess immediate program outcomes by comparing baseline data collected a week before the first day of training with data collected within 2 weeks of the final day of the program. We administer pre- and postassessments to participants as web-based surveys using Qualtrics version XM (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah). Evaluation instruments assess self-reported levels of experience and confidence in mentorship-related skills before and after program participation. (For the pre–post CO-Mentor assessment, please refer to Supplemental Digital Appendix 1, at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A790.) Assessments feature both fixed-choice response and open-ended items. We conducted paired samples t tests to examine increased experience applying the specific tools and techniques that serve as the focus of the curriculum (as an indicator of fidelity of program implementation) and growth in confidence in mentorship-related skills (i.e., self-efficacy to apply these skills to any mentorship relationship). To help ensure that data were representative of each construct, we calculated a mean score only when individual respondents answered 75% of the associated items. We also conducted thematic analysis of qualitative or open-ended responses, with codebook development (i.e., codes and associated definitions) informed by an understanding of the program, relevant theoretical constructs, and knowledge of the field of academic mentorship and its relationship to career/professional development.

During the 2014–2015 to 2016–2017 academic years, 158 individuals participated in CO-Mentor. This included 79 mentors and 79 mentees in an existing mentorship relationship who participated as mentor–mentee dyads or triads. (Over this period, 3 mentors participated with more than 1 mentee.) Figures 1 and 2 present the demographic characteristics of program participants who comprised these 3 consecutive cohorts. The majority of mentees (66%; n = 52/79) and mentors (56%; n = 44/79) were female. The largest percentage of mentors were consistently senior faculty (i.e., rank of associate or full professor). Mentees tended to be junior faculty or fellows.

Figure 1.

Participants’ academic rank at the time of program participation (2014–2015, 2015–2016, and 2016–2017 cohorts compared).

Figure 2.

Gender representation of participants (2014–2015, 2015–2016, and 2016–2017 cohorts compared). Abbreviations: F, female; M, male.

Not all of the program participants responded to the evaluation survey; also, response rates varied from item to item on the surveys. Three-fourths (76%) of participants completed both the pre- and postassessments (mentors: n = 56; mentees: n = 64). On the presurvey, we asked mentee enrollees how long the mentorship relationship represented in the program had been established. Seventy-six mentees answered this survey item in the presurvey. Forty-two percent of mentee respondents (n = 32/76) indicated that the relationship with the participating mentor had been established within the previous 1 to 2 years. A slightly lower percentage (37%) of mentee respondents (n = 28/76) indicated that the relationship was established 3 or more years before program participation.

Enhancing Mentorship Skills and Related Support for Mentees and Mentors

Increased confidence in mentorship-related skills

Both mentors and mentees reported statistically significant growth in confidence with respect to all mentorship-related skills assessed (P < .001). Table 1 displays the items from most to least growth (pre to post) for mentors and mentees. Mentors reported the most growth in relation to 2 areas: networking to engage social and professional support to realize goals and sharing insights regarding paths to success. Mentees reported the most growth in confidence with respect to connecting with potential/future mentors, knowing what characteristics to look for in current/future mentors, and managing the work environment (e.g., prioritizing work most fruitful to advancing research and career objectives).

Table 1.

CO-Mentor Pre–Post Survey Respondents’ Self-Reported Growth in Confidence

| Pre |

Post |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey item | Average | SD | Average | SD | Differencea |

| Mentor survey item (n = 56 mentors) | |||||

| Networking to engage social and professional support to realize my goalsb | 3.24 | 0.950 | 4.00 | 0.752 | 0.76 |

| Sharing insights regarding paths to success | 3.64 | 0.762 | 4.36 | 0.558 | 0.72 |

| Managing work environment (e.g., tasks and timelines, prioritizing work most fruitful to advancing research and career objectives, etc.)b | 3.35 | 0.935 | 4.00 | 0.727 | 0.65 |

| Providing constructive feedback to mentees | 3.51 | 0.891 | 4.11 | 0.670 | 0.60 |

| Discerning and applying insights about interpersonal communication stylesb | 3.43 | 0.866 | 3.96 | 0.649 | 0.53 |

| Encouraging work choices that promote growth and persistence | 3.79 | 0.638 | 4.31 | 0.639 | 0.52 |

| Ability to recommend potential mentors | 3.63 | 0.808 | 4.13 | 0.674 | 0.50 |

| Providing guidance according to mentees’ interests/needs | 3.83 | 0.666 | 4.31 | 0.577 | 0.48 |

| Providing professional and social support to mentees | 3.83 | 0.720 | 4.28 | 0.656 | 0.45 |

| Mentee survey item (n = 64 mentees) | |||||

| Connecting with potential/future mentors (e.g., knowing how to approach them) | 2.92 | 0.885 | 3.97 | 0.761 | 1.05 |

| Knowing what characteristics to look for in current/future mentors | 3.32 | 0.997 | 4.33 | 0.568 | 1.01 |

| Managing work environment (e.g., tasks and timelines, prioritizing work most fruitful to advancing research and career objectives, etc.)b | 3.06 | 0.931 | 3.79 | 0.722 | 0.73 |

| Creating career development plans | 3.40 | 0.943 | 3.94 | 0.669 | 0.54 |

| Networking to engage social and professional support to realize my goalsb | 3.06 | 1.203 | 3.59 | 0.909 | 0.53 |

| Articulating goals and progress toward their achievement with mentor | 3.57 | 0.946 | 4.08 | 0.747 | 0.51 |

| Discerning and applying insights about interpersonal communication stylesb | 3.35 | 0.845 | 3.86 | 0.800 | 0.51 |

| Asking for feedback and/or advice about career objectives | 3.75 | 0.861 | 4.16 | 0.653 | 0.41 |

Abbreviations: CO-Mentor, Colorado Mentoring Training program; SD, standard deviation.

A significant difference was found for all items, which are displayed from highest to lowest average difference pre to post; P < .001.

Items asked of both mentors and mentees.

The survey presented mentors and mentees with unique items based on their specified role in the program. However, we asked both mentor and mentee participants to assess their confidence in the following skills: managing the work environment (e.g., ability to prioritize tasks most pivotal to longer-term success), discerning and applying insights about interpersonal communication styles, and networking to engage social and professional support to realize goals. Mentees, as a group, reported larger gains in confidence than mentors with respect to managing the work environment (difference of +0.73 compared with +0.65). However, mentors demonstrated the most growth in relation to networking to engage social and professional support to realize goals (difference of +0.76 compared with +0.53) and slightly more growth in discerning and applying insights about interpersonal communication styles (difference of +0.53 compared with +0.51).

Expanded mentorship support networks

We designed CO-Mentor to give participants new awareness and language regarding the different types of support and corresponding mentorship relationships that should comprise their mentorship support networks to foster intentionality in developing these relationships. Further, we seek to foster the development of skills in purposeful networking to engage different types of mentors to address identified gaps in support. To explore evidence that mentees’ enhanced awareness and self-efficacy resulted in the application of new/improved mentorship-related skills in practice, the evaluation examined changes in mentees’ mentorship support networks over time. Specifically, the pre–post assessments asked about both the types of mentors represented in their mentorship support networks and, for the 2 most recent cohorts, the absolute number of mentors that comprised these networks. Their responses demonstrate that mentorship support networks expanded on both dimensions.

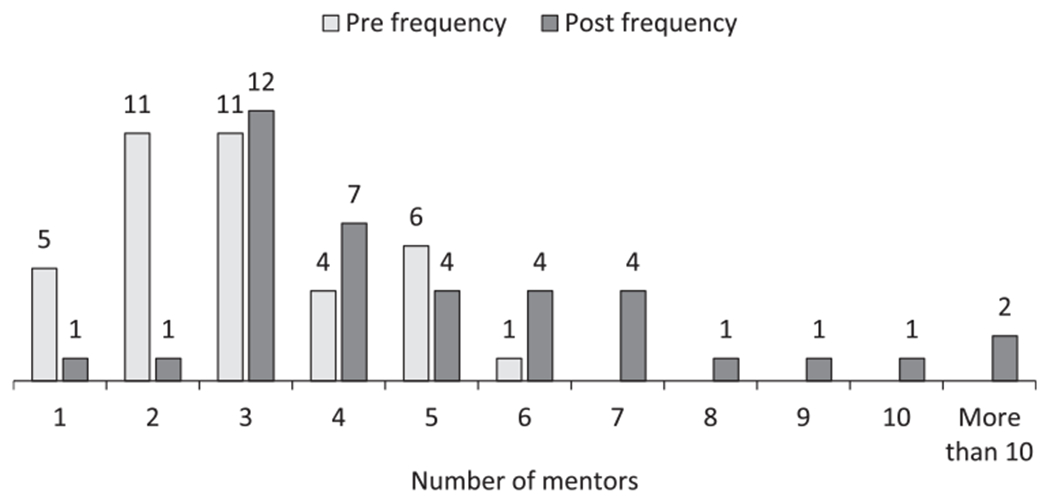

With regard to the absolute number of mentors, 71% of mentees (27 of 38 respondents from the 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 cohorts and for whom both pre- and postassessments were available) reported having more mentors following program participation. Figure 3 shows the associated shift in the number of mentors reported pre to post. On average, mentees reported having 3 mentors before program participation. If we omit the 2 respondents who reported having “more than 10 mentors” at the conclusion of the training, mentees reported having an average of 5 mentors immediately following the training.

Figure 3.

Number of mentors that mentees reported comprising their mentorship support networks (pre- and postassessment results compared; n = 38).

Pre–post assessments also presented a list of the types of mentors (adapted from Johnson et al13) that would ideally comprise one’s mentorship support network. These were: Lead mentor (has overall responsibility for guiding and supporting the development of research, career, and well-being), career mentor (provides guidance regarding career development, professional networking, and promotion opportunities), research mentor (offers guidance about study design, analysis, institutional review board issues), and peer mentor (support that may be similar to that listed above but provided by someone of similar rank and/or level of experience). Four survey items explored the types of mentors that comprised mentees’ support networks; 64 mentees answered these survey items on both the pre- and postevaluation surveys. By the conclusion of CO-Mentor, mentees were more likely to report or recognize having peer mentors (59%, n = 38/64 compared with 34% initially, n = 22/64). More mentees also reported having access to career mentors following program participation (80%, n = 51/64 compared with 64%, n = 41/64). In fact, career mentor was the type of mentorship support most frequently reported by mentee respondents at the time of the postassessment.

Mentees: Essential to Institutional Capacity for Effective Mentorship

Growth in knowledge, skills, and self-reported efficacy to apply new or enhanced mentorship-related competencies is essential to clinical and translational research workforce development and is equally salient to mentors and mentees. Historically, mentorship training opportunities have tended to target mentors, without the direct involvement of mentees. In contrast to these traditional training approaches, our local approach to mentorship development values the mentee as essential to our institutional capacity for effective mentorship. This view drives us to invest as much in the development of the mentees’ skills as it does the mentors’. Thus, we strive to equip both with tools and resources to engage effectively in mutually beneficial and rewarding mentorship relationships. When given the tools, training, and supported opportunities to practice applying associated skills, mentees can identify and articulate what they need and take purposeful action to address those needs.

CO-Mentor, developed as part of a suite of education, training, and career development programs for the CCTSI, is to our knowledge unique among CTSA programs in the equal emphasis given to supporting the development of mentorship-related skills among both mentors and mentees. Furthermore, CO-Mentor trains mentors and mentees in existing relationships as dyads, providing enhanced opportunities to practice skills using the products of mentorship (e.g., individual career development plans, personal statements, letters of support, CV development).

Importantly, while mentors and mentees complete the training and associated activities as dyads, the program helps individuals develop knowledge and skills that are transferrable to any mentoring relationship. Evaluation results suggest that mentor and mentee participants were able to expand their mentorship support networks during the program. The expansion of peer mentorship, in particular, is an important finding given that the program seeks to promote connection to affinity groups (i.e., peers) and institutional connectedness—aspects of “relatedness” that are predictors of job satisfaction and retention/persistence in a field.15,16 The extent to which individuals who have had specific training in effective mentorship stay at the institution, specifically, and engaged in academia, more generally, also bodes well for promoting an academic environment of effective mentorship.

The finding that mentees often are the impetus for their mentors to participate in CO-Mentor highlights their potential to serve as catalysts for effective mentorship in the clinical and translational sciences. Without an external motivating influence, it may be difficult for more senior investigators to prioritize participation in a formal mentorship training program, especially one that is relatively more intensive (i.e., requires a significant time commitment over the course of an academic year). This inference seems especially salient for clinical and translational researchers given the complexity of their work and professional roles. Senior clinical and translational researchers may not actively seek or commit to mentorship training given the constellation of demands emanating from their clinical, research, teaching, and administrative leadership responsibilities. The structure of CO-Mentor may help overcome these barriers by leveraging the relationship and associated commitment a mentor may feel toward an existing mentee. On preassessments, mentors often reported that they decided to participate in CO-Mentor at the encouragement or request of their mentee. Accountability to one another may also help explain the consistently high attendance rates characteristic of program participants.

CO-Mentor emphasizes self-knowledge and effective communication for both mentors and mentees, which are hallmarks of leadership development.17 For this reason, a structured mentorship training program, which invests directly in mentees as well as mentors, may be an ideal first step toward more targeted leadership development in the clinical and translational sciences. Within the context of the CCTSI, our leadership training pathways include the Leadership for Innovative Team Science program.18

Concluding Observations

To optimize the potential benefits of the mentoring relationship, both mentees and mentors should receive specialized training that will prepare them to leverage the resources inherent in this relationship and to make mutually beneficial contributions. The ongoing need for CO-Mentor is evidenced by full enrollment and waiting lists every year, repeat participation by mentors and former mentee participants with new mentees, and endorsement from other CCTSI programs (e.g., the NIH KL2 Mentored Clinical Research Scholar program requires scholars to complete CO-Mentor with their primary mentors). Although CO-Mentor is an intensive program, evaluation results obtained over consecutive cohorts demonstrate high demand and high levels of program satisfaction and completion.

The CO-Mentor program evaluation (pre–post design) explored proximal outcomes in terms of how the training affected knowledge, skills, and self-reported confidence in key theoretically informed areas relevant to mentorship. While our findings, aggregated for 3 consecutive cohorts, are promising, these data stop short of providing the evidence necessary to determine program impact on participants’ research, their work lives (including attainment of leadership positions and promotion), and their respective academic divisions and departments—future directions for longitudinal program evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Colorado Mentoring Training program has been offered annually since 2010. The 400 past participants—200 mentors and mentees, respectively—provided the opportunity to refine the curriculum. Similarly, participants in the workshop “Two to Tango: Mentoring in Academic Medical Centers” at the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) National Meeting in 2013, presented by Drs. Emma Meagher, Ellen Seely, Jane EB Reusch, and Anne Libby, are acknowledged.

Funding/Support: Funding support has been provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Center for Colorado CTSA Grant number UL1 TR002535.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A790.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus advised that this work does not constitute research or warrant human subjects review.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Contributor Information

Kathryn A. Nearing, Division of Geriatrics, Center on Aging, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, and associate director for education and evaluation, VA Eastern Colorado Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), Aurora, Colorado.

Bridget M. Nuechterlein, The Evaluation Center, University of Colorado Denver, School of Education and Human Development, Denver, Colorado, and Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CCTSI), Aurora, Colorado.

Shuyuan Tan, The Evaluation Center, University of Colorado Denver, School of Education and Human Development, Denver, Colorado, and CCTSI, Aurora, Colorado.

Judy T. Zerzan, Washington State Health Care Authority, Olympia, Washington.

Anne M. Libby, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Anschutz Medical Campus, and CCTSI, Aurora, Colorado.

Gregory L. Austin, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, School of Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, and CCTSI, Aurora, Colorado.

References

- 1.Meagher E, Taylor L, Probsfield J, Fleming M. Evaluating research mentors working in the area of clinical translational science: A review of the literature. Clin Transl Sci. 2011;4:353–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tillman RE, Jang S, Abedin Z, Richards BF, Spaeth-Rublee B, Pincus HA. Policies, activities, and structures supporting research mentoring: A national survey of academic health centers with clinical and translational science awards. Acad Med. 2013;88:90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keyser DJ, Lakoski JM, Lara-Cinisomo S, et al. Advancing institutional efforts to support research mentorship: A conceptual framework and self-assessment tool. Acad Med. 2008;83:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellanos J, Gloria AM, Kamimura M, eds. The Latina/o Pathway to the Ph.D.: Abriendo Caminos. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daley S, Wingard DL, Reznik V. Improving the retention of underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1435–1440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manson SM. Personal journeys, professional paths: Persistence in navigating the crossroads of a research career. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 1):S20–S25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nearing KA, Hunt C, Presley JH, Nuechterlein BM, Moss M, Manson SM. Solving the puzzle of recruitment and retention-strategies for building a robust clinical and translational research workforce. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8:563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen TD, Lentz E, Day R. Career success outcomes associated with mentoring others: A comparison of mentors and nonmentors. J Career Dev. 2006;32:272–285. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coates WC. Being a mentor: What’s in it for me? Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zerzan JT, Hess R, Schur E, Phillips RS, Rigotti N. Making the most of mentors: A guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84:140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, Lovett M, O’Sullivan P. Does mentoring matter: Results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:5063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman MD, Huang L, Guglielmo BJ, et al. Training the next generation of research mentors: The University of California, San Francisco, Clinical & Translational Science Institute Mentor Development Program. Clin Transl Sci. 2009;2:216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson MO, Subak LL, Brown JS, Lee KA, Feldman MD. An innovative program to train health sciences researchers to be effective clinical and translational research mentors. Acad Med. 2010;85:484–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martina CA, Mutrie A, Ward D, Lewis V. A sustainable course in research mentoring. Clin Transl Sci. 2014;7:413–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lechuga VM, Lechuga D C. Faculty motivation and scholarly work: Self-determination and self-regulation perspectives. J Professor. 2012;6:59–97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Libby AM, Hosokawa PW, Fairclough DL, Prochazka AV, Jones PJ, Ginde AA. Grant success for junior faculty in patient-oriented research: Difference-in-differences evaluation of a mentored research training program. Acad Med. 2016;91:1666–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Libby AM, Cornfield DN, Abman SH. There is no “I” in team: New challenges for career development in the era of team science. J Pediatr. 2016;177:4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Libby AM, Ingbar DH, Nearing KA, Moss M, Albino J. Developing senior leadership for clinical and translational science. J Clin Transl Sci. 2018;2:124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.