Abstract

Background

Lidocaine is the gold standard local anesthetic (LA) for UK pediatric dental treatment. Recent reports suggest frequent Articaine use in Europe and Canada, with evidence indicating more profound anesthesia. The aim of this study was to examine pediatric dentistry specialist experiences and practices relating to Articaine administration in the UK.

Methods

A literature review was followed by a survey using an anonymous 15-item electronic questionnaire, which was sent to 200 registered British Society of Pediatric Dentistry (BSPD) specialists. Descriptive analyses, Z score, chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, and Spearman's correlation test were performed.

Results

Sixty-one (30.5%) participants responded, and 12 (19.7%) indicated Articaine as their first line anesthetic. Articaine was used daily or weekly by 38 (62.3%) respondents, depending on the clinical context. Articaine was commonly used to avoid inferior alveolar nerve blocks and gain more profound anesthesia in abscessed or hypomineralized teeth. Participants reported significantly more adverse effects with lidocaine (Fisher's exact test, P < 0.0001) than with Articaine. Articaine was most often administered in children aged > 4 years via infiltration techniques. Only 15 (24.6%) respondents reported awareness of guidelines for Articaine use in pediatric patients.

Conclusions

Articaine use in pediatric dentistry is common; however, evidence supporting its practice is limited. Several specialists follow conventions based on anecdotal evidence. Formulating guidance to aid decision-making when treating pediatric patients under LA would be beneficial.

Keywords: Articaine, Local anesthesia, Pain, Pediatric dentistry

INTRODUCTION

Local anesthesia (LA) dates back to 1884 with the application of Cocaine, from which the first recognized LA agent, Procaine, an amino ester, was synthesized. In the 1940–50s, amide LA agents were introduced, including Lidocaine and Mepivacaine. These were more potent than Procaine, and they produced fewer allergic reactions; thus, they were considered better LA agents, with Lidocaine becoming the new ‘gold standard’. In 1969, Articaine was introduced to the market – a ‘hybrid’ amide containing an ester-group thiophene ring. The thiophene ring increases lipid solubility (ability to diffuse through the cortical bone and myelin sheath) and potency. Articaine is unique; 90% is metabolized in the plasma by esterase hydrolysis, instead of in the liver where 95% of Lidocaine is metabolized, and it has a lower half-life [1].

LA is performed to alleviate pain and discomfort, facilitate cooperation, and reduce dental anxiety in patients who require invasive procedures. The scope of practice of the General Dental Council [2] outlines LA administration as a core skill for dentists and dental therapists.

Studies have shown that Lidocaine is the ‘gold standard’ for adult and pediatric patients in dental school local guidelines [3]. Several pediatric dental guidelines recommend LA before invasive treatments and state recommended dosages; however, none of them indicate the use of Articaine over Lidocaine or vice versa [4,5]. Therefore, several dentists guide their decisions with experience and reports from clinical studies.

The gold standard local anesthetic varies worldwide; several European countries (Italy, France, Germany, and the Netherlands) and Canada predominantly use Articaine as their first-line anesthetic [1]. It has been reported that Articaine is more than 90% of the LA used by dentists in Germany [6,7]. In the UK, Lidocaine is currently the most popular local anesthetic used in general dental practices for both adult and pediatric patients. However, Articaine sales have been rising, reaching just under 10 million cartridges in 2008 [8]; a study reported that Articaine tends to be used more frequently by newly qualified dentists [9]. This difference in opinion could be due to the conflicting literature on Articaine's efficacy and safety, which are two crucial properties for an ideal local anesthetic. In an age where evidence-based dentistry is at the forefront of dental undergraduate education, guidance on the use of Articaine may aid decision-making when treating pediatric patients in the UK.

The aims and objectives of this study were to examine current practices and experiences of pediatric dentistry specialists in relation to Articaine use as a local anesthetic.

METHODS

Following a thorough literature review, a survey questionnaire was developed and revised by the authors. The questionnaire was based on previous study questionnaires and consisted of 15 items which included multiple-choice and open-ended long answer questions [9,10]. The items focused on LA, especially in relation to Articaine practices and attitudes. The estimated survey participation duration was 10 minutes. The questionnaire was piloted and amended before approval by the Dental School Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 1708a).

Following approval from the British Society of Pediatric Dentistry (BSPD) officials, the questionnaire was distributed electronically via email to all UK, General Dental Council (GDC), and BSPD registered pediatric dentistry specialists. As of 2016, the target cohort consisted of 200 specialists. The email was distributed between February and October 2017, with follow-up emails sent on two separate occasions to encourage participation. The survey was strictly anonymous and voluntary, with the freedom to withdraw at any time. Using G*Power power analysis software, a sample size of 60 participants was determined with a power of 80% to detect differences of 15%.

Participant responses were recorded electronically and anonymously in preparation for data collection. The data set was subsequently prepared and statistically analyzed using SPSS. Descriptive analyses were used, as well as the Z-score, chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, and Spearman's correlation test. The findings were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 200 specialists in pediatric dentistry invited to participate in the questionnaire, 61 responded (Table 1), which satisfied our sample size requirement. The year of pediatric dentistry specialization ranged from 1987 to 2016, from which years of experience as a pediatric specialist was calculated and categorized; 39.3% had between 11 and 20 years of pediatric dentistry experience. Participants graduated from several dental schools across the UK; these were classified into regions, with 47.5% graduating from a dental school in England. Sex and age were not considered in this study.

Table 1. Study participants' demographic details.

| Region of graduation (Cities) | n = 61 (%) | Years of experience as a pediatric specialist | n = 61 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| England (London, Newcastle, Liverpool, Birmingham, Sheffield, Manchester) | 29 (47.5%) | 21+ | 3 (4.9%) |

| Wales (Cardiff) | 4 (6.6%) | 11 to 20 | 24 (39.3%) |

| Scotland (Dundee, Glasgow, Edinburgh) | 12 (19.7%) | 6 to 10 | 11 (18%) |

| Northern Ireland (Belfast) | 4 (6.6%) | 5 or less | 20 (32.8%) |

| Other countries | 8 (13.1%) | Undisclosed | 3 (4.9%) |

| Undisclosed | 4 (6.6%) |

1. Freqency of administration and first-line anesthetic

The first-line local anesthetic and the frequency of administration for each agent are shown in Table 2. Lidocaine was the most common first-line local anesthetic (n = 49, 80.3%), and it was significantly more likely to be administered daily than Articaine (Fisher's exact test, P = 0.001); 51.7% (n = 31) of the participants reported daily Lidocaine administration, whereas only 23% (n = 14) reported the daily use of Articaine. The majority of participants who chose Articaine as their first line local anesthetic graduated from Northern Ireland (Belfast) (Fisher's exact test, P = 0.0263). However, the number of years of specialist experience and the use of Articaine as a first-line anesthetic had no significant correlation. There were no significant associations between the frequency of use of either anesthetic and the region of graduation or the years of specialist experience.

Table 2. Reported frequency of Lidocaine and Articaine administration by participants, and first-line local anesthetics stratified by region of graduation and years of specialist experience.

| Frequency of use | Lidocaine (n = 60) | Articaine (n = 61) |

|---|---|---|

| daily* | 31 (51.7%) | 14 (23.0%) |

| weekly | 22 (36.7%) | 24 (39.3%) |

| monthly | 1 (1.7%) | 6 (9.8%) |

| infrequently | 6 (10.0%) | 17 (27.9%) |

| Fisher's exact P-value = 0.001* |

*indicates significant values.

‘Other/Undisclosed’ was not included in statistical comparisons

2. LA administration – age range, adrenaline concentration, and technique

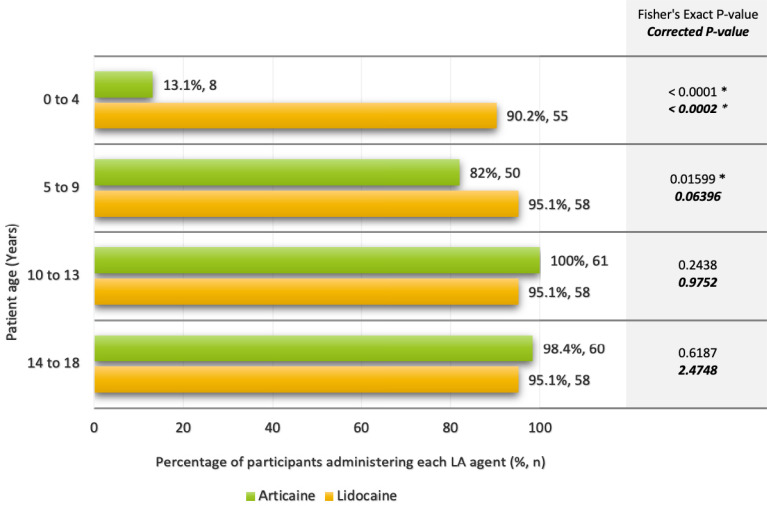

The majority of participants (n = 55, 91.7%) stated that they would administer lidocaine in pediatric patients aged 0–4 years, whereas only 8 (13.1%) would administer Articaine to the same age group (Fisher's exact test, P < 0.0002). A marginally non-significant association between LA administration and the 5–9 years group was also observed (Fisher's exact test, P = 0.06396), following a multiple testing correction (Fig. 1). This suggests Articaine avoidance with decreasing age, with a more robust association with the 0–4 years age group. However, four participants indicated that they would not administer both anesthetics to children aged 0–4 years; the local anesthetic they would use in this cohort of patients is unclear.

Fig. 1. Reported use of Lidocaine and Articaine by participants, according to pediatric patient age groups (*indicates significant values).

A variation in the preference of Articaine adrenaline concentration was noted:

• 68.9% (n = 42) of participants used 1:100,000 adrenaline

• 21.3% (n = 13) of participants used 1:200,000 adrenaline

• 9.8% (n = 6) of participants used both 1:100,000 or 1:200,000 adrenaline

There were no significant associations between the preference for adrenaline concentrations and years of specialist experience or region of graduation.

Regarding the method of administration of Articaine, 98.4% (n = 60) of the respondents indicated buccal infiltrations as their preference, with 54.1% (n = 33) and 14.8% (n = 9) indicating intra-ligamental and intra-papillary infiltrations, respectively, as their supplementary methods of administration. In relation to administration techniques being avoided when using Articaine, 95.1% (n = 58) of participants stated that they would not administer Articaine using inferior alveolar nerve blocks (IANB); 7 respondents further indicated that they would not administer any forms of nerve blocks, including mental blocks or infra-orbital blocks, using this local anesthetic. The reasons cited for IANB avoidance included the risk of prolonged paresthesia (n = 13), the risk of nerve injury or damage (n = 10), and reported neurotoxicity (n = 5). One respondent stated that they would avoid administering intra-ligamental infiltrations using Articaine; however, no reason was specified.

3. Articaine selection criteria

The participants identified various procedures for which they would opt to use Articaine, which included restorations (n = 58), pulp treatment (n = 38), extractions (n = 57), preparation of teeth for the application of preformed metal crowns (n = 22), and surgical procedures (n = 5).

The reasons stated for the use of Articaine as a local anesthetic were:

• Avoidance of IANB – to reduce discomfort, patient distress, and the risk of soft tissue trauma (n = 21)

• Increased effectiveness for abscessed, infected, or hypomineralized lower molars (n = 10)

• More profound, successful, and predictable analgesia (especially in cases where Lidocaine has failed) (n = 18)

• Reduced risk of toxicity due to the lower dosage required (n = 1)

However, 36 contraindications were stated for the use of Articaine in certain situations by 50.8% of the respondents (n = 31), as summarized in Table 3. A large proportion (58.3%, n = 21) of the contraindications stated were related to young children, specifically those under the ages of 4–5 years; the aim was to reduce the risk of soft tissue trauma, and due to the fact that Articaine was not licensed in this age group. Of the contraindications related to medical history (30.6%, n = 11), 54.5% (n = 6) were associated with allergic reactions to the constituents of the anesthetics such as preservatives or amide compounds.

Table 3. Contra-indications, as stated by 50.8% of participants (n = 31), for the use of Articaine.

| Contra-indications | Number of times stated (n = 36) (%) |

|---|---|

| Young children (under 4-5 years of age) | 21 (58.3%) |

| Children with additional needs or biting habits | 4 (11.1%) |

| Medical history | 11 (30.6%) |

| Allergy | 6 (54.5%) |

| Interaction with other medications | 1 (9.1%) |

| Liver disease | 1 (9.1%) |

| Renal disease | 1 (9.1%) |

| Asthma | 1 (9.1%) |

| Cardiac disorders | 1 (9.1%) |

4. Frequency of adverse effects

Adverse effects following LA, as illustrated in Table 4, included prolonged paresthesia, soft tissue trauma, and diplopia; these were reported by 42.6% of the participants. A significantly larger proportion of reported adverse effects following LA occurred with lidocaine (84.6%) than with Articaine (15.4%) (Fisher's exact test, P < 0.0001); the odds of adverse effects was 8.11 greater when using lidocaine than when using Articaine, considering the frequency of use. There were no significant associations between reported adverse effects and the frequency of administration of either of the local anesthetics individually. Additionally, there was no association between the Articaine adrenaline concentration and the reported adverse effects. Prolonged paresthesia, as an adverse effect, was reported equally within both cohorts at a minimal level, while soft tissue trauma was the most reported adverse effect.

Table 4. Adverse effects reported by specialists in pediatric dentistry following the use of Lidocaine and Articaine.

| Reported adverse effects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Anesthetic | Prolonged paraesthesia | Soft tissue trauma | Diplopia | Total (n = 26) | ||

| Lidocaine | 2 | 19 | 1 | 22 (84.6%) | ||

| Articaine | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 (15.4%) | ||

5. Knowledge of guidelines relating to Articaine

The majority of participants (n = 46, 75.4%) stated that they were unaware of any guidelines for administrating Articaine in pediatric patients; of this cohort, 13% (n = 6) used Articaine as their first line anesthetic, and 19.6% (n = 9) used Articaine daily. Of the 15 participants (24.6%) who stated that they were aware of guidelines, 66.7% (n = 10) referred to the guidelines of the American Association of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) (2015) [11].

DISCUSSION

The aim of this survey study was to obtain insights into the UK perspective on LA, especially in relation to the practices and attitudes toward Articaine usage in pediatric dentistry. A convenience sample of BSPD GDC-registered UK specialists was chosen due to their daily practice within pediatric dentistry. It is acknowledged that the 33.5% response rate is a weakness of this study. The low response rate could have been a result of the length of the questionnaire and the limited free time of the specialists.

This study found that a large proportion of specialists in pediatric dentistry (80.3%) considered Lidocaine to be their first choice. However, Articaine is used frequently; 62.3% stated that they used it daily and weekly. A significant association was found between choosing Articaine as the first line anesthetic and graduating from Northern Ireland (Belfast). This may be a result of variations in the local guidelines adopted in different dental schools. A study exploring the teaching of LA to dental students revealed that 14 dental schools in the UK used Articaine; however, only 1 dental school stated Articaine as their first line LA for pediatric patients, while 5 dental schools stated that Articaine was not to be used in either adult or pediatric patients [3]. No significant associations were found between years of specialist experience and the choice of the first-line anesthetic, the frequency of use of an anesthetic, or Articaine adrenaline concentrations. However, the study had a low power for detecting potential effects as a result of the small sample size.

The avoidance of Articaine administration in children between the ages of 0–4 years may be due to the manufacturer's information found within the Septanest Data Sheet, which states that 4% Articaine 1:100,000 adrenaline should only be used in children aged 4 years and above [12]; clinical trials excluded patients below this age group. However, several studies have supported the use of Articaine in children aged < 4 years old, recommending it because of its high potency, reduced toxicity, and lower recommended dosage when compared to Lidocaine, coupled with a low occurrence of adverse effects [3,10,13].

Infiltrations and IANBs are the two most common local anesthetic delivery methods in clinical dentistry. Within this study, a large proportion of participants stated that they avoided IANBs and administered Articaine through buccal infiltrations. This route of administration for Articaine has largely been pre-determined by the fact that it is not recommended for administration through IANBs in children in some countries [14]. The reasons cited by participants for IANB avoidance with Articaine included the risk of prolonged paresthesia, the risk of nerve injury or damage, and reported neurotoxicity. There are conflicting opinions in the literature on the potential neurotoxicity of Articaine if administered as an IANB. One study established that IANBs may cause nerve injury using any local anesthetic, regardless of the agent used; 25% of incurred injuries were associated with Lidocaine and 33% with articaine [15,16]. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis concluded that there was no increased incidence of adverse events when comparing Articaine to Lidocaine in IANBs [17].

The avoidance of IANBs was commonly used to justify Articaine use, as well as the more profound and predictable analgesia in cases where Lidocaine failed and more effective analgesia for abscessed or hypomineralized lower molars. Evidence reinforces the former justification, as IANBs are more painful in children than buccal infiltration techniques as a result of the higher volume, longer duration of injection, and penetration of multiple deeper structures by the needle [6,18,19]. Regarding the effectiveness of Articaine for abscessed or hypomineralized molars, several studies have reported that supplementing a Lidocaine IANB with Articaine via buccal infiltration provides more profound and successful pulpal anesthesia in patients presenting with irreversible pulpitis [20,21]; however, the studies comparing the effectiveness of Lidocaine and articaine in hypomineralized molars in pediatric patients are limited. More recently, articaine delivered through intraosseous injection has been found to be effective and safe for achieving profound anesthesia in MIH-affected teeth with severe hypersensitivity related to chronic pulpal inflammation in children [22]. Additionally, a systematic review by Tong et al. reported less patient-reported pain after the procedure following LA with Articaine, indicating additional benefits of its use [14].

Of the contraindications stated by respondents in relation to the use of Articaine, 30.6% (n = 11) were related to medical history; of these, 54.5% (n = 6) referred to allergic reactions to the constituents of the anesthetics. Although hypersensitivities are documented in the literature, true allergies to amide LA agents are considered rare [23]. Hypersensitivities are commonly associated with common preservatives such as methylparaben and sodium metabisulphite [24]. Additionally, sulfites and sulfiting agents, such as sodium metabisulphite, have been found to induce asthmatic symptoms; therefore, caution is advised in children with severe asthma [25]. Renal and liver disease and cardiac disorders were also mentioned by participants as contraindications for the use of Articaine. As the metabolism and elimination of local anesthetics generally depend on the normal function of the liver and kidney(s), there is a theoretical risk of metabolite accumulation and systemic toxicity in patients with severe renal and hepatic impairment [26]. The British National Formulary advises caution when using any local anesthetic in patients with severe hepatic or renal impairment [27]. In patients with severe hypertension or unstable cardiac rhythm, the use of adrenaline with a local anesthetic may be hazardous; local anesthetics should be used without adrenaline and accidental intravascular injection should be prevented [27]. However, there is no evidence that Articaine poses a higher risk in these patients than other local anesthetics.

A large proportion (58.3%) of the contraindications stated for the use of Articaine were related to young children, specifically those under the ages of 4–5 years; the aim was to reduce the risk of soft tissue trauma, and due to the fact that Articaine was not licensed for this age group. Several studies have demonstrated self-induced soft tissue injuries as common complications of local anesthesia in young children under the ages of 6–7 years. However, studies have generally demonstrated no significant differences between the number of soft tissue injuries incurred with the use of Lidocaine and articaine [28,29]. Conversely, the results of this study suggest that pediatric specialists had experienced more adverse effects (prolonged paresthesia, soft tissue trauma, and diplopia) with Lidocaine, despite taking into consideration its higher frequency of use. This contradicts the reports by previous literature suggesting that there are no significant differences between the adverse effects of Lidocaine and articaine and they are associated with an equal likelihood of incidents [6,14,18,19,30]. On the other hand, clinical studies comparing the risk of adverse effects from IANBs and infiltrations when using both Articaine and Lidocaine found that IANBs were most commonly associated with significantly more adverse effects than infiltrations [31,32]. As IANBs are most often used with Lidocaine, it is expected that these reactions are more commonly associated with this anesthetic.

The majority of participants (75.4%) were unaware of any pediatric guidelines for Articaine use. The AAPD [11], (the most commonly stated guideline for the use of Articaine) does not state that Articaine cannot be used in children younger than 4 years, or that it increases the risk of soft tissue trauma, or that it should not be administered via an IANB.

The data collected from this study shows that while Lidocaine is still the most commonly used local anesthetic by specialists in pediatric dentistry, Articaine is safe and effective for use in pediatric patients. The most common justifications for avoiding Articaine administration in children were ages below 4 years, avoiding the risk of soft tissue trauma, and avoiding IANBs. However, the most commonly known local anesthetic guideline on Articaine usage from the AAPD (2015) does not confirm these common attitudes and opinions. Future research should focus on these areas to address professional concerns. Additionally, formulating UK guidelines to aid decision-making when treating pediatric patients under LA would be beneficial.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Renata Medeiros-Mirra (Cardiff University) for her support and advice while we were conducting the final statistical analyses.

Footnotes

- Maryam Ezzeldin: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing — original draft, Writing — review & editing

- Gemma Hanks: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing — original draft, Formal analysis

- Mechelle Collard: Conceptualization, Supervision

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

NOTE: Results previously presented at the British Society of Pediatric Dentistry (BSPD) Conference located in Dundee, Scotland (UK) - September 2018

References

- 1.Johansen O. Comparison of Articaine and Lidocaine Used as Dental Local Anesthetics. 2004. Available from http://endoexperience.com/userfiles/file/unnamed/articaine%20vs%20lidocaine.pdf.

- 2.General Dental Council. Scope of Practice. 2013. Available from https://www.gdc-uk.org/api/files/Scope%20of%20Practice%20September%202013.pdf.

- 3.Oliver G, David DA, Bell C, Robb N. An investigation into dental local anaesthesia teaching in united kingdom dental schools. SAAD Dig. 2016;32:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) Prevention And Management Of Dental Caries In Children: Dental Clinical Guidance. 2018. Available from http://www.sdcep.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SDCEP-Prevention-and-Management-of-Dental-Caries-in-Children-2nd-Edition.pdf.

- 5.American Association of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) Guideline on Use of Local Anesthesia for Pediatric Dental Patients. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malamed S, Gagnon S, Leblanc D. A comparison of Articaine HCL and Lidocaine HCL in pediatric dental patients. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22:307–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malamed S, Gagnon S, Leblanc D. Articaine hydrochloride: a study of the safety of a new amide local anesthetic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:177–185. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartlett G, Mansoor J. Articaine buccal infiltration vs lidocaine inferior dental block – a review of the literature. Br Dent J. 2016;220:117–120. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corbett IP, Ramacciato JC, Groppo FC, Meechan JG. A survey of local anaesthetic use among general dental practitioners in the UK attending postgraduate courses on pain control. Br Dent J. 2005;199:784–787. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brickhouse TH, Unkel JH, Webb MD, Best AM, Hollowell RL. Articaine use in children among dental practitioners. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:516–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Association of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) Guidelines On Use Of Local Anaesthesia For Pediatric Dental Patients. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivoclar Vivadent Ltd. Septanest: Articaine hydrochloride 4% with adrenaline 1:100,000. Available from https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/Datasheet/s/Septanestinj.pdf.

- 13.Wright GZ, Weinberger SJ, Friedman CS, Plotzke OB. The use of articaine local anaesthesia in children under 4 years of age – a retrospective report. Anesth Prog. 1989;36:268–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong HJ, Alzahrani FS, Sim YF, Tahmassebi JF, Duggal M. Anaesthetic efficacy of articaine versus lidocaine in children's dentistry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018;28:347–360. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pogrel A. Permanent nerve damage from inferior alveolar nerve blocks: a current update. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2012;40:795–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunne B. The conventional inferior alveolar nerve block: is there a more predictable alternative? J Ir Dent Assoc. 2018;64:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su N, Li C, Wang H, Shen J, Liu W, Kou L. Efficacy and safety of articaine versus lidocaine for irreversible pulpitis treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Aust Endod J. 2016;42:4–15. doi: 10.1111/aej.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ram D, Amir E. Comparison of articaine 4% and lidocaine 2% in paediatric dental patients. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2006;16:252–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chopra R, Marwaha M, Bansal K, Mittal M. Evaluation of buccal infiltration with articaine and inferior alveolar nerve block with lignocaine for pulp therapy in mandibular primary molars. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2016;40:301–305. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-40.4.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews R, Drum M, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M. Articaine for supplemental buccal mandibular infiltration anesthesia in patients with irreversible pulpitis when the inferior alveolar nerve block fails. J Endod. 2009;35:343–346. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM, Corbett IP, Meechan JG. Articaine buccal infiltration enhances the effectiveness of lidocaine inferior alveolar nerve block. Int Endod J. 2009;42:238–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixit UB, Joshi AV. Efficacy of intraosseous local anesthesia for restorative procedures in molar incisor hypomineralization-affected teeth in children. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018;9:s272–s277. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_252_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bina B, Hersh EV, Hilario M, Alvarez K, McLaughlin B. True allergy to amide local anesthetics: a review and case presentation. Anesth Prog. 2018;65:119–123. doi: 10.2344/anpr-65-03-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simonet D. Hypersensitive reactions to local dental anesthetics and patient information: critical review of a drug leaflet. Local Reg Anesth. 2011;4:35–40. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S16479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vally H, Misso NL. Adverse reactions to the sulphite additives. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2012;5:16–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snoeck M. Articaine: a review of its use for local and regional anesthesia. Local Reg Anesth. 2012;5:23–33. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S16682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.BNF British National Formulary - NICE [Internet] Bnf.nice.org.uk; 2020. [cited 23 June 2020]. Available from: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagattoni S, D'Alessandro G, Gatto M, Piana G. Self-induced soft-tissue injuries following dental anesthesia in children with and without intellectual disability. A prospective study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2020;21:617–622. doi: 10.1007/s40368-019-00506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adewumi A, Hall M, Guelmann M, Riley J. The incidence of adverse reactions following 4% septocaine (articaine) in children. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:424–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leith R, Lynch K, O'Connell AC. Articaine use in children: A review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2012;13:293–296. doi: 10.1007/BF03320829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaffen AS, Haas DA. Retrospective review of voluntary reports of nonsurgical paresthesia in dentistry. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75:579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garisto GA, Gaffen AS, Lawrence HP, Tenenbaum HC, Haas DA. Occurrence of paresthesia after dental local anesthetic administration in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:836–844. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]