Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has the potential to develop into hepatic steatosis and progress to terminal liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. This human clinical study was aimed to demonstrate that SPB-201 (powdered-water extract of Artemisia annua) can improve liver function in subjects with non-alcoholic liver dysfunction at mild to moderate levels. A decrease of 271% in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level and a significant decrease of 334% in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level was observed in the test group as compared to the control group at the 4 weeks follow-up. In addition, after 8 weeks, decreases of 199% in AST level and 216% in ALT level were reported in the test group as compared to the control group. These results confirmed that SPB-201 intake significantly enhanced liver function and health. Moreover, the Multidimensional Fatigue Scale score of the test group decreased but that of the control group increased, implicating that SPB-201 also eliminated overall fatigue. No significant adverse events were observed among all subjects during the study. Taken together, our clinical study confirmed the excellent efficacy and safety of SPB-201 in liver function improvement, showing the possibility of SPB-201 as a functional food to restore liver dysfunction and treat liver diseases.

Keywords: Artemisia annua, NAFLD, Clinical study, Fatigue, Functional food

INTRODUCTION

According to statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 4.5 million American adults have liver disease, accounting for 1.8% of the total population in 2018 [1]. The death rate among patients with chronic liver disease increased from 21.9 per 100,000 population in 2007 to 24.9 in 2016, increasing by 1.3% per year for men and 2.5% for women. The death rate from among patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), in particular, which accounts for 34.7% of chronic liver diseases, increased by 2.1% per year from 7.3 per 100,000 population in 2007 to 9.0 in 2006 [2]. As of 2015, out of the 143.9 million people with major chronic diseases in South Korea, 1.49 million have liver disease [3]. NAFLD has not received much attention due to its relatively mild clinical prognosis, however, it has the potential to develop into hepatic steatosis and progress to terminal liver disease such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [4,5].

In a cohort study on 420 NAFLD patients with a mean follow-up of 7.6 years, cirrhosis occurred in 3% cases [6]. Liver cirrhosis occurred in 0.9% of 109 NAFLD patients in 16.7-year study and in 1.2% of 170 NAFLD patients in 20.4-year study [7,8]. In Korea, the prevalence of NAFLD is rapidly increasing reaching 27.3%, which is believed to be largely attributed with stress and Westernization of diet [9,10,11].

Depending on the underlying cause, liver diseases can be classified as viral-induced, alcoholic, toxic (drug-induced), fat-accumulating, autoimmune, and metabolic liver diseases [12]. Since liver cells may gradually be destroyed and lose more than half of their functional capacities without any specific symptoms, it is therefore important to maintain normal liver function and prevent liver failure [13]. Although lifestyle correction and medication are the current standard treatments for liver diseases, there is a concern about the safety of long-term administration of drugs, and further studies on their effectiveness are needed.

Artemisia annua L., one of the most widely distributed wormwood in Korea, has shown excellent pharmacological efficacy against a wide range of diseases such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, obesity, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia and cardiovascular disease, and further demonstrated anti-gastritis, and anti-ulcer effects, all of which are derived from its strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

In a previous study using a high fat diet (HFD)-induced fatty liver mouse model, A. annua extract maintained normal liver weight in non-induced fatty liver mice and showed histologically similar patterns to that in non-induced normal liver mice, but not in the HFD-induced group. In addition, the A. annua extract improved the blood levels of aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), and hepatic triglyceride (TG) by 40% in both the HFD-induced and the non-treated group and reduced the total blood cholesterol (TC) to near normal levels. It was also confirmed that expression of phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase (p-AMPK) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (p-ACC) in the liver tissues of mice treated with A. annua extract increased to near-normal levels, while the expressions of fatty acid synthase (FAS) and sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-1c decreased. Similar results were shown in in vitro studies of lipid metabolic gene expressions using the HpeG2 cell line [25,26,27]. In addition, in the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/D-galactosamine (GalN)-induced liver failure mouse model, A. annua extract reduced AST and ALT levels, and protected the hepatocyte from fatal liver damage. In the in vitro test using the Raw264.7 cell line, it was proved that hepato-protective effect of A. annua extract came through the reduction of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and nitric oxide (NO) [28].

Therefore, this human clinical study was conducted to verify the effectiveness and safety of 8-week SPB-201 (powdered, water extract of A. annua [WEAA]) therapy in improving the liver function of subjects with liver function impairments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This human clinical study was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonization of Good Clinical Practice (ICH GCP) guidelines, Korean GCP (KGCP), and the Helsinki Declaration. In addition to the standard guidelines of the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety and the pre-approved protocol of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul Sahmyook Medical Center (SYMC IRB 1808) and Bundang Jesaeng Hospital (IMCN IRB 18-04). IRB was approved for launching on August 8, 2018 and for completion in SYMC IRB 1808 and IMCN IRB 18-04 respectively in May 14, and June 1, 2020. All participating subjects (or legal representatives) were provided sufficient explanation prior to written consent. All study procedures and data were checked by regular monitoring.

Subjects and study design

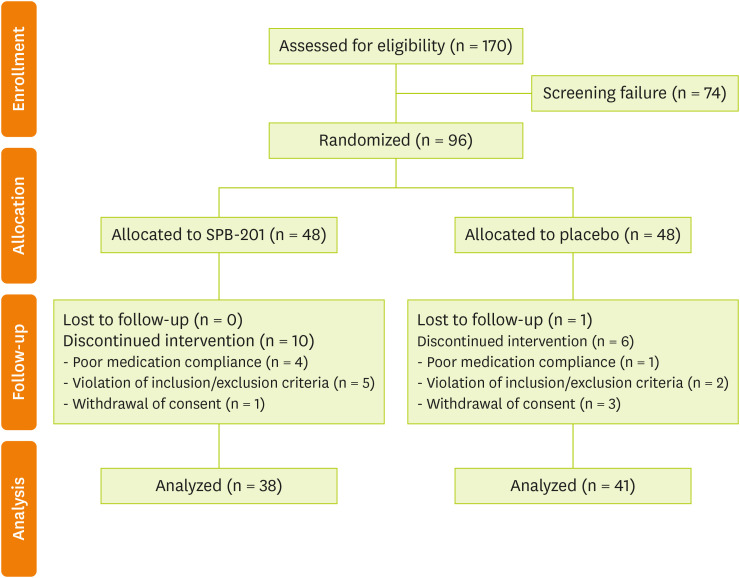

In this human clinical study, 170 participants were screened based on the election/exclusion criteria, through which 74 subjects were eliminated, leaving a total of 96 subjects to be randomly assigned into the two groups (n = 48 in each group). At the end of the study, 4 subjects from the test group dropped out due to violation of the selection/exclusion criteria, and 1 withdrew consent while 3 subjects from the control group withdrew consent, and 1 dropped out due to loss of follow-up. A total of 87 subjects completed the study (test group, n = 43 and control group, n = 44) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of participants, recruitment, and randomization of the study.

Per protocol (PP) analysis set was defined as a subject who completed the study and does not have any serious violations (selection/exclusion criteria violation, etc.) that affected study result. Three cases of selection criteria violation (ALT > 120 U/L; test group, n = 1 and control group, n = 2) and 5 cases of inadequate compliance (test group, n = 4 and control group, n = 1) were excluded. The PP analysis set eventually composed of 79 subjects (test group, n = 38 and control group, n = 41) (Figure 1).

The subjects selected were adult men and women with borderline and mild liver dysfunction with blood AST or ALT in the range of 45–120 U/L. Selected subjects who voluntarily participated in the study, were randomly assigned to either the test group or control group according to the registration order, and were evaluated in parallel for 8 weeks (56 days). Those who were treated for alcohol use or induced disorder, those with liver dysfunction such as cirrhosis, liver cancer, or hepatitis, and who took drugs that affect liver function were excluded. The test group consumed A. annua hot water extract powder (SPB-201, 686 mg/2 tablets/day [solids based on 480 mg/day] twice a day in the morning and evening). Placebos, which contain crystallin cellulose instead of SPB-201, were provided to the control group in the same manner.

Sample collection and laboratory assessment

Follow-ups were carried out at weeks 4 and 8 and involved the following tests; 1) Occurrence of adverse events, 2) Changes in combination therapy, 3) Physical examinations (clinical evaluation for abnormality in respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, endocrine, reproductive, musculoskeletal, and nervous systems), 4) Vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, and bio-impedance) 5) Physical measurements (height and weight), 6) Clinical pathology tests (hematological examination, hemochemical test, urine test, etc.), 7) Electrocardiography (ECG), 8) Multidimensional Fatigue Scale (MFS, survey for evaluation in global fatigue severity, daily dysfunctional fatigue, and situation-specific fatigue), 9) Drinking and smoking habits (survey on the average, amount and frequency of the week during the previous month), 10) Dietary habits (to maintain the usual diet and dietary intake and not to regularly consume mugwort-related foods), 11) Compliance, 12) Excising habits (survey for the average, duration and frequency of the week during the previous month).

The main outcome parameter of the clinical study is the amount and rate of change in blood AST and ALT after 4 and 8 weeks of ingestion of the substances. In addition, the MFS and blood cholesterol were confirmed as parameters for efficacy.

Statistical analysis

Statistically analyses were performed using SAS® (Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics (number of subjects, average, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values) were presented for patient's demographics and clinical characteristics. For numerical data comparing the amount of change before and after the test, a 2-sample t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed depending on normality satisfaction. Categorical data were presented as frequency and ratio, and the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was conducted for independence verification. Significant probability values are presented for all results.

In the analysis of safety endpoints, all subjects who consumed the test substance or placebo after randomization were included. For the analysis of the efficacy evaluation variables, only the test subjects who have completed the study without any serious violations that would affect study results (such as, selection/exclusion criteria violation, etc.) were included. The data obtained were presented as mean and standard deviation, and were considered significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

This human clinical study was designed to demonstrate that SPB-201 improves liver function of subjects with non-alcoholic liver dysfunction at mild to moderate levels. Compounding factors were assessed by comparing all patient demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1). The test group included 26 men (68.42%) and 12 women (31.58%), while the control group included 32 men (78.05%) and 9 women (21.95%). There were no statistically significant differences in the gender between the groups. The average age was 48.00 ± 12.63 years and 49.20 ± 12.94 years in the test and control groups, respectively, with no statistically significant differences. Body weight was 76.02 ± 16.15 kg and 77.45 ± 15.93 kg, respectively, with no significant difference between groups. The body mass index (BMI) (calculation using body weight in kilograms [kg] and height in meters squared [m2]) was also not significantly different between the test and control groups, averaging at 26.65 ± 3.87 kg/m2 and 27.53 ± 4.26 kg/m2, respectively. In addition, no statistically significant differences were observed for exercise, smoking status, smoking amount, smoking period, notification method, among others. The comparability between the randomly assigned groups was therefore confirmed prior to initiation of administration of SPB-201 and the placebo.

Table 1. Baseline participants demographics and clinical characteristics.

| Clinical characteristics | SPB-201 (n = 38) | Placebo (n = 41) | Total (n = 79) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.3331† | ||||

| Male | 26 (68.42) | 32 (78.05) | 58 (73.42) | ||

| Female | 12 (31.58) | 9 (21.95) | 21 (26.58) | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.6794* | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 48.00 ± 12.63 | 49.20 ± 12.94 | 48.62 ± 12.73 | ||

| Min–Max | 20.00–67.00 | 19.00–73.00 | 19.00–73.00 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 0.6881* | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 76.02 ± 16.15 | 77.45 ± 15.93 | 76.77 ± 16.05 | ||

| Min–Max | 48.1–117.4 | 53.2–144.5 | 48.1–144.5 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.3499* | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 26.65 ± 3.87 | 27.53 ± 4.26 | 27.10 ± 4.10 | ||

| Min–Max | 18.24–34.79 | 22.48–47.73 | 18.24–47.73 | ||

| Exercise | 0.8229‡ | ||||

| No | 14 (36.84) | 18 (43.90) | 32 (40.51) | ||

| 1–2 times/week | 9 (23.68) | 12 (29.27) | 21 (26.58) | ||

| 3–4 times/week | 10 (26.32) | 8 (19.51) | 18 (22.78) | ||

| 5–6 times/week | 3 (7.89) | 2 (4.88) | 5 (6.33) | ||

| Everyday | 2 (5.26) | 1 (2.44) | 3 (3.80) | ||

| Smoking | 0.2203† | ||||

| No | 22 (57.89) | 20 (48.78) | 42 (53.16) | ||

| Ex-smoker (over a year) | 3 (7.89) | 9 (21.95) | 12 (15.19) | ||

| Smoker | 13 (34.21) | 12 (29.27) | 25 (31.65) | ||

| HFD | 0.8381† | ||||

| No | 4 (10.53) | 6 (14.63) | 10 (12.66) | ||

| 1–2 times/week | 27 (71.05) | 27 (65.85) | 54 (68.35) | ||

| 3 or more/week | 7 (18.42) | 8 (19.51) | 15 (18.99) | ||

SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; HFD, high fat diet.

*The p value by 2 sample t-test; †p value by χ2 test; ‡p value by Fisher's exact test.

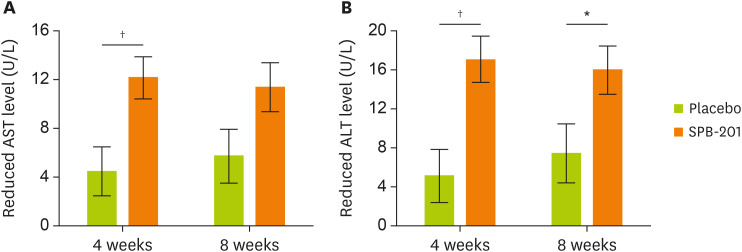

In the analysis of the AST level changes at the 4-week follow-up, mean AST level in the test group decreased by 12.16 ± 12.41 U/L (p < 0.0001), while that in the control group decreased by 4.49 ± 11.27 U/L (p = 0.0147). Significant differences were demonstrated between the 2 groups (p = 0.0045 and p = 0.0421; 2 sample t-test and Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively). At the 8-week follow-up, these reduced by 11.39 ± 13.58 U/L (p < 0.0001) in the test group, and by 5.71 ± 12.71 U/L (p = 0.0017) in the control group. Although there was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (p = 0.0626), the decrease in AST levels in the test group was more prominent than that in the control group, and showed a clear improvement (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Changes in serum concentrations of AST and ALT in SPB-201-intake subjects.

Serum levels of AST and ALT were measured before (week 0) randomization of the subjects. All subjects were followed-up at 4 weeks and 8 weeks after the study. (A) The trend of decrease in AST levels from weeks 0, 4, to 8. (B) The trend of decrease in ALT levels from weeks 0, 4, or 8. The white bar represents the reduction trend of the placebo group, while the dark bar represents the that of the SPB-201 test group. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (placebo group, n = 41 and test group, n = 38).

AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

*p < 0.05, †p < 0.01.

In the analysis of ALT level changes at the 4-week follow-up, mean ALT level in the test group decreased by 17.05 ± 16.89 U/L (p < 0.0001) and that in the control group decreased by 5.10 ± 15.22 U/L (p = 0.0381). Significant differences were observed between the two groups (p = 0.0014 and p = 0.0030; 2 sample t-test and Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively). At the 8-week follow-up, the change in mean ALT level in the test group decreased by 15.97 ± 18.82 U/L (p < 0.0001), and that in the control group decreased by 7.41 ± 15.90 U/L (p = 0.0048). There was a statistically significant difference in ALT level changes between the two groups at both the 4-week (p = 0.0014) and 8-week (p = 0.0317) follow-ups, reflecting remarkable improvement in liver function with SPB-201 (Figure 2B).

In the AST change rate analysis, after 4 weeks of substance intake, the test group showed a decrease by 0.23 ± 0.21 U/L and the control group showed a decrease by 0.11 ± 0.25 U/L, with statistically significant differences between the 2 groups (p = 0.0144). After 8-week follow-up, statistically significant differences were not observed between the 2 groups, but the AST change rate of the test group decreased by 0.21 ± 0.22 U/L, and that of the control group decreased by 0.13 ± 0.26 U/L. The AST reduction rate of the test group was dramatically reduced and maintained throughout the study (Supplementary Figure 1).

After 4-week follow-up from substance uptake, the ALT change rate decreased in the test group by 0.26 ± 0.24 U/L and in the control group decreased by 0.09 ± 0.28 U/L, showing statistically significant differences between the two groups (p = 0.0063). No statistically significant differences were not observed between the groups after 8-week follow-up, but ALT reduction rate of the test group was 0.24 ± 0.26 U/L, and that of the control group was 0.14 ± 0.30 U/L clearly indicating that the ALT improvement rate of the test group was superior to that of the control group (Supplementary Figure 2).

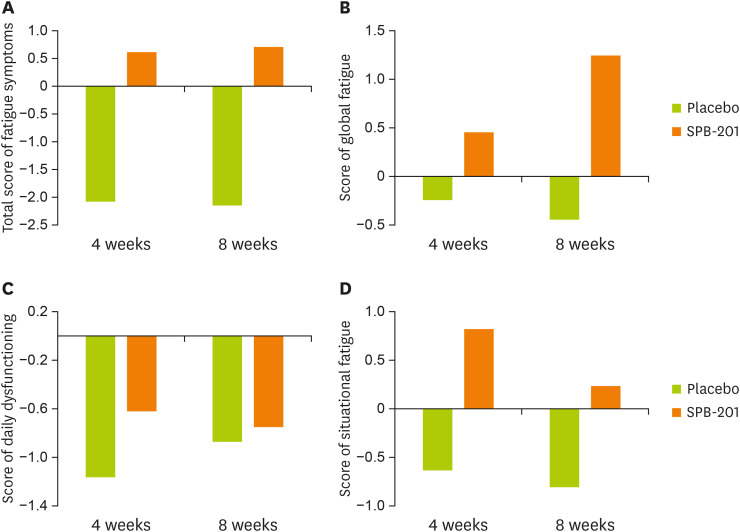

With regard to the total change in the MFS, the test group showed improvement by 0.63 ± 12.21 and 0.71 ± 15.40 points after 4 and 8-week follow-up, respectively, while the control group showed deterioration by 2.05 ± 11.92 and 2.12 ± 11.99 points. The differences in MFS between the 2 groups increased with time (Figure 3A). Regarding changes in daily life dysfunctional fatigue, after 4-week and 8-week follow-up, the test group showed improvement of 0.45 ± 5.59 and 1.24 ± 5.63 points, respectively, while the control group showed exacerbation by 0.24 ± 5.90 and 0.44 ± 5.77 points respectively (Figure 3B). Global fatigue severity improved by 0.82 ± 6.66 points and 0.24 ± 7.87 points, respectively, in the test group and showed a tendency to increase the fatigue rate by 0.63 ± 6.15 points and 0.80 ± 6.06 points respectively in the control group (Figure 3D). After both time points, the overall fatigue level of the test group decreased but that of the control group increased, demonstrating that SPB-201 intake eliminated overall fatigue.

Figure 3. Changes in MFS in the test group.

All registered subjects were followed-up before (week 0) and after substance intake (weeks 4 and 8) for evaluation of the MFS. (A) The total score of MFS consisted of (B) global fatigue severity, (C) daily dysfunctional fatigue, and (D) situation-specific fatigue. The change of each fatigue scores from weeks 0 to 4 or 8 of each group are indicated. The white bar represents the change in the placebo group, while the dark bar represents that in the SPB-201 test group. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (placebo group, n = 41 and test group, n = 38).

MFS, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale.

The total cholesterol of the test group ingesting SPB-201 decreased by 20% compared to the control group. In particular, the low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol of the test group decreased by 6.03 ± 23.14 mg/dL after 8 weeks of administration, while the control group increased by 0.02 ± 21.08 mg/dL, but there was no statistical significance between the intake groups (data not shown).

The safety endpoint analysis was conducted on a total of 87 subjects who completed the clinical study (test group, n = 43 and control group, n = 44). The test items were derived from hematologic tests (Table 2) and hemochemical tests (Table 3). Hematological analyses included white blood cell (WBC) count, red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin (Hb) level, hematocrit (Hct), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and platelet, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, eosinophil, and basophile counts. After 8-week follow-up, Hct of the test group decreased by 1.33% ± 2.11% (p = 0.0002), and that of the control group decreased by 0.47% ± 1.85% (p = 0.1011). Although differences were borderline significant (p = 0.0462) between groups, the change within groups before and after the study were subtle and within normal range. Platelet count was decreased by 8.88 ± 29.75 ×103/µL in the test group (p = 0.0006), and increased by 1.45 ± 27.54 ×103/µL in the control group (p = 0.7278), showing statistically significant difference between 2 groups (p = 0.0037). Again, the difference before and after the tests of both groups were within normal range. All the other hematologic parameters did not show significant differences between the 2 groups. The hemochemical tests included total protein, albumin, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), uric acid (UA), calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), potassium (K), and chloride (Cl) levels. In all of the categories, no statistically significant differences were observed in the study.

Table 2. Change of hematological parameters.

| Hematological parameters | SPB-201 | Placebo | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean ± SD | No. | Mean ± SD | |||

| WBC (103/µL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 6.05 ± 1.51 | 48 | 6.28 ± 1.58 | 0.4704† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 6.08 ± 1.13 | 44 | 6.49 ± 1.62 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | 0.08 ± 1.48 | 44 | 0.22 ± 1.11 | 0.5637† | |

| RBC (106/µL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 4.96 ± 0.46 | 48 | 4.88 ± 0.40 | 0.3460* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 4.84 ± 0.49 | 44 | 4.81 ± 0.40 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.12 ± 0.24 | 44 | −0.06 ± 0.21 | 0.1729† | |

| Hb (g/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 15.18 ± 1.35 | 48 | 15.06 ± 1.15 | 0.8173† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 14.77 ± 1.45 | 44 | 14.86 ± 1.13 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.41 ± 0.70 | 44 | −0.15 ± 0.61 | 0.0687* | |

| Hct (%) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 44.86 ± 3.89 | 48 | 44.26 ± 3.13 | 0.4180† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 43.62 ± 4.24 | 44 | 43.69 ± 3.34 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −1.33 ± 2.11 | 44 | −0.47 ± 1.85 | 0.0462* | |

| MCV (FL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 90.55 ± 4.03 | 48 | 90.91 ± 4.58 | 0.6799* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 90.34 ± 4.28 | 44 | 90.93 ± 4.20 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.52 ± 1.99 | 44 | 0.02 ± 1.98 | 0.3287† | |

| Platelet (103/µL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 254.50 ± 54.01 | 48 | 266.90 ± 56.01 | 0.2725* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 238.35 ± 46.65 | 44 | 268.73 ± 57.46 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −16.88 ± 29.75 | 44 | 1.45 ± 27.54 | 0.0037* | |

| Segmented neutrophil (%) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 53.39 ± 8.73 | 48 | 52.16 ± 8.30 | 0.4800* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 53.09 ± 8.74 | 44 | 52.31 ± 8.42 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.37 ± 7.26 | 44 | 0.87 ± 6.45 | 0.4018* | |

| Lymphocyte (%) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 35.78 ± 7.89 | 48 | 37.94 ± 7.90 | 0.1828* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 36.38 ± 8.48 | 44 | 37.67 ± 7.60 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | 0.71 ± 7.34 | 44 | −0.85 ± 5.62 | 0.2683* | |

| Monocyte (%) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 6.96 ± 1.44 | 48 | 6.61 ± 1.60 | 0.2236† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 6.97 ± 1.91 | 44 | 6.44 ± 1.52 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | 0.04 ± 1.36 | 44 | −0.23 ± 1.12 | 0.3250* | |

| Eosinophil (%) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 3.23 ± 2.80 | 48 | 2.68 ± 1.66 | 0.4635† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 3.36 ± 3.64 | 44 | 2.90 ± 2.09 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | 0.04 ± 1.48 | 44 | 0.14 ± 1.53 | 0.9425† | |

| Basophil (%) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 0.68 ± 0.29 | 48 | 0.63 ± 0.22 | 0.3472* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 0.71 ± 0.39 | 44 | 0.69 ± 0.29 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | 0.04 ± 0.29 | 44 | 0.05 ± 0.24 | 0.5714† | |

WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume

Compared between groups: *p value by 2 sample t-test; †p value by Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Table 3. Change of hemochemical parameters.

| Hemochemical parameters | SPB-201 | Placebo | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean ± SD | No. | Mean ± SD | |||

| Protein (g/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 7.50 ± 0.43 | 48 | 7.50 ± 0.42 | 1.0000* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 7.36 ± 0.30 | 44 | 7.37 ± 0.39 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.15 ± 0.33 | 44 | −0.13 ± 0.27 | 0.7373* | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 4.53 ± 0.25 | 48 | 4.53 ± 0.29 | 0.9057† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 4.42 ± 0.23 | 44 | 4.44 ± 0.26 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.12 ± 0.20 | 44 | −0.08 ± 0.19 | 0.3283† | |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 0.91 ± 0.40 | 48 | 0.84 ± 0.39 | 0.2588† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 0.83 ± 0.40 | 44 | 0.80 ± 0.33 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.09 ± 0.23 | 44 | −0.05 ± 0.29 | 0.4853* | |

| ALP (U/L) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 166.58 ± 93.94 | 48 | 148.15 ± 75.77 | 0.3953† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 167.79 ± 96.37 | 44 | 145.80 ± 73.49 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | 0.02 ± 20.07 | 44 | −0.70 ± 19.09 | 0.8953† | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 100.94 ± 13.74 | 48 | 105.58 ± 21.27 | 0.4524† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 102.91 ± 15.07 | 44 | 105.39 ± 15.70 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | 3.44 ± 14.22 | 44 | 1.23 ± 11.80 | 0.5102† | |

| BUN (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 14.59 ± 3.81 | 48 | 13.88 ± 3.90 | 0.5048† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 14.71 ± 3.75 | 44 | 13.95 ± 4.48 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | 0.06 ± 3.76 | 44 | 0.10 ± 3.82 | 0.9524* | |

| Cr (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 0.86 ± 0.18 | 48 | 0.84 ± 0.17 | 0.5481* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 0.83 ± 0.16 | 44 | 0.82 ± 0.17 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.02 ± 0.08 | 44 | −0.01 ± 0.08 | 0.3678† | |

| UA (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 6.10 ± 1.75 | 48 | 5.98 ± 1.42 | 0.8575† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 5.96 ± 1.64 | 44 | 6.05 ± 1.36 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.14 ± 0.80 | 44 | 0.04 ± 0.73 | 0.1996† | |

| Ca (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 9.39 ± 0.78 | 48 | 9.35 ± 0.39 | 0.3890† | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 9.29 ± 0.29 | 44 | 9.20 ± 0.33 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.10 ± 0.81 | 44 | −0.15 ± 0.31 | 0.5636† | |

| Na (mmol/L) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 139.52 ± 2.37 | 48 | 139.48 ± 1.77 | 0.9302* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 139.42 ± 1.88 | 44 | 139.32 ± 1.95 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.23 ± 2.72 | 44 | −0.31 ± 1.86 | 0.7693† | |

| K (mmol/L) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 4.36 ± 0.37 | 48 | 4.38 ± 0.33 | 0.8166* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 4.24 ± 0.34 | 44 | 4.33 ± 0.34 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | −0.14 ± 0.38 | 44 | −0.06 ± 0.34 | 0.2844* | |

| Cl (mmol/L) | ||||||

| Baseline | 48 | 103.26 ± 2.79 | 48 | 103.56 ± 2.33 | 0.5685* | |

| Week 8 | 43 | 103.63 ± 2.47 | 44 | 103.77 ± 2.11 | ||

| Change from baseline | 43 | 0.47 ± 2.66 | 44 | 0.02 ± 1.95 | 0.3752* | |

ALP, alkaline phosphate; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; UA, uric acid; Ca, calcium; Na, sodium; K, potassium; Cl, chloride.

Compared between groups: *p value by 2 sample t-test; †p value by Wilcoxon rank sum test.

DISCUSSION

It has been reported that A. annua L., one of the most commonly distributed wormwood in Korea, has excellent pharmacological efficacy against a wide range of diseases. In the previous studies on HFD-induced fatty liver mouse model, SPB-201 was shown to maintain the normal liver weight of fatty liver mice and inhibited lipid accumulation in the liver. In addition, SPB-201 improved liver function indicators, blood AST, ALT and TG levels by more than 40% and reduced TC to near normal values [25,26,27]. A. annua extract significantly increased the p-AMPK and p-ACC, resulting in suppression of adipogenesis and prevention of lipid accumulation in the liver of HFD-fed mice [25]. The ability of A. annua extract in reducing AST and ALT levels and in protecting the hepatocyte from fatal liver damage was further confirmed in the LPS/D-GalN-induced liver failure mouse model. A. annua extract has shown to contain strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, resulting in effective treatment for fatty liver disease and protection from the liver failure [28].

Excess accumulation of fat in the liver accompanying chronic inflammation renders the high risk of progression into chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis and liver cancer [4,5]. Considering the anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative actions of A. annua from pre-clinical studies, SPB-201 was expected to improve liver function in this clinical study.

We therefore aimed to verify the effectiveness and safety of SPB-201 for 8 weeks in improving liver function in subjects with liver function impairment. The efficacy evaluation variables for liver function were the extent of changes in the levels of the typical liver enzymes AST and ALT, which normally help with protein metabolism and energy generation [29]. AST and ALT are secreted into the blood in cases of liver damage and/or liver diseases.

After 4 weeks of SPB-201 intake, we found a decrease of 271% in AST levels, and a 334% reduction in ALT levels as compared to the control. After 8 weeks of SPB-201 intake, the test group showed an AST reduction of 199% and a significant ALT decrease of 216% as compared to the control group. This demonstrated that SPB-201 intake has the effect of improving the function of AST and ALT. Unlike ALT, which is mainly present only in the liver, AST is widely distributed in the muscles, heart, internal organs, and brain as well. Therefore, ALT can be used as a specific indicator of liver function. In this clinical study, the ALT level of the test group was significantly reduced after 4 weeks as compared to the control group, and decreased progressively until the end of the study, indicating a distinct effect of SPB-201 on improving liver function and maintaining liver health.

The fatigue scale can be used as a measure of liver dysfunction, and the total score for global fatigue severity, situation-specific fatigue, and daily dysfunctional fatigue is evaluated as MFS [30,31,32,33]. After 4 weeks and 8 weeks of substance intake, the fatigue score of the test group decreased while that of the control group increased. It can therefore be judged that overall fatigue may be resolved through the improvement of liver function by SPB-201.

In this study, we confirmed the safety of the test substance SPB-201. No significant adverse events were observed in tall subjects during the study and no significant differences in adverse events were observed between groups even though there were 9 adverse events from the 7 test subjects and 14 from the 11 control subjects. In addition, no clinically meaningful side effects related to SPB-201 were observed. Hematological examination showed significantly different changes in Hct between the two groups after 8 weeks of intake (p = 0.0462). The normal levels of red blood cell volume (Hct) are 39%–52% for men and 36%–48% for women, and the changes in both groups were minor and within the normal range from 44.86% to 43.62% and 44.26% to 43.69%, respectively. Platelet count decreased by 8.88 ± 29.75 ×103/µL in the test group but increased by 1.45 ± 27.54 ×103/µL in the control group, showing statistical differences between them (p = 0.0037). The normal platelet count range between 150–450 ×103/µL and the platelet levels of both groups before and after the study were within the normal ranges. Besides these, there were no signs of abnormality in the remaining clinical pathology parameters and no differences between the groups. Thus, we confirmed that oral SPB-201 intake for 8 weeks is clinically effective and safe.

CONCLUSION

Taken together, our clinical study confirmed the excellent efficacy and safety of SPB-201 on liver function improvement, showing that SPB-201 can be developed into a functional food to restore damaged liver function such as in non-alcoholic fatty livers, or to treat liver diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Chan Young Park, Eun-Yong Choi, Doori Choi, and Hyeyoung Lee for their excellent thechnical supports and Dr. Heejin Yang and Dr. Seong-Hyun Ho for their insightful discussion.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (IPET) through High Value-added Food Technology Development Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) No. 2017100491.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Reduction rate of AST.

Reduction rate of ALT.

References

- 1.CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. [cited 2020 July 15]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/liver-disease.htm.

- 2.Paik J, Golabi P, Sayinern M, Biswas R, Alqahtani S, Venkatesan C, Younossi ZM. The increase in mortality related to chronic liver disease is explained by non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Hepatology. 2018;68:763. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baek H, Son J, Shin J. Comparison of severe disease incidence among eligible insureds to expand coverage for substandard risks. J Health Info Stat. 2018;43:318–328. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong VW, Wong GL, Choi PC, Chan AW, Li MK, Chan HY, Chim AM, Yu J, Sung JJ, Chan HL. Disease progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study with paired liver biopsies at 3 years. Gut. 2010;59:969–974. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.205088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang XJ, Malhi H. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:ITC65–80. doi: 10.7326/AITC201811060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, Angulo P. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:113–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dam-Larsen S, Franzmann M, Andersen IB, Christoffersen P, Jensen LB, Sørensen TI, Becker U, Bendtsen F. Long term prognosis of fatty liver: risk of chronic liver disease and death. Gut. 2004;53:750–755. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.019984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunn W, Xu R, Wingard DL, Rogers C, Angulo P, Younossi ZM, Schwimmer JB. Suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and mortality risk in a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2263–2271. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeon JH, Park KG. Definition, pathogenesis, and natural progress of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Korean Diabetes. 2014;15:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SH, Plank LD, Suk KT, Park YE, Lee J, Choi JH, Heo NY, Park J, Kim TO, Moon YS, Kim HK, Jang HJ, Park HY, Kim DJ. Trends in the prevalence of chronic liver disease in the Korean adult population, 1998–2017. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2020;26:209–215. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2019.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim S, Taskinen MR, Borén J. Crosstalk between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiometabolic syndrome. Obes Rev. 2019;20:599–611. doi: 10.1111/obr.12820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, George J, Bugianesi E. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iqbal S, Younas U, Chan KW, Zia-Ul-Haq M, Ismail M. Chemical composition of Artemisia annua L. leaves and antioxidant potential of extracts as a function of extraction solvents. Molecules. 2012;17:6020–6032. doi: 10.3390/molecules17056020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim WS, Choi WJ, Lee S, Kim WJ, Lee DC, Sohn UD, Shin HS, Kim W. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of artemisinin extracts from Artemisia annua L. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015;19:21–27. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2015.19.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park HJ, Cho JY, Kim MK, Koh PO, Cho KW, Kim CH, Lee KS, Chung BY, Kim GS, Cho JH. Anti-obesity effect of Schisandra chinensis in 3T3-L1 cells and high fat diet-induced obese rats. Food Chem. 2012;134:227–234. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreiber A, Härter G, Schubert A, Bunjes D, Mertens T, Michel D. Antiviral treatment of cytomegalovirus infection and resistant strains. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:191–209. doi: 10.1517/14656560802678138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song Y, Lee SJ, Jang SH, Kim TH, Kim HD, Kim SW, Won CK, Cho JH. Annual wormwood leaf inhibits the adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 and obesity in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Nutrients. 2017;9:554. doi: 10.3390/nu9060554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim MH, Seo JY, Liu KH, Kim JS. Protective effect of Artemisia annua L. extract against galactose-induced oxidative stress in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexei L, Eba A, Benhilda NM, et al. Integrating medicinal plants extraction into a high-value biorefinery: an example of Artemisia annua L. C R Chim. 2014;17:232–241. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang M, Guo MY, Luo Y, Yun MD, Yan J, Liu T, Xiao CH. Effect of Artemisia annua extract on treating active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Chin J Integr Med. 2017;23:496–503. doi: 10.1007/s11655-016-2650-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunt S, Stebbings S, McNamara D. An open-label six-month extension study to investigate the safety and efficacy of an extract of Artemisia annua for managing pain, stiffness and functional limitation associated with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. N Z Med J. 2016;129:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Efferth T, Dunstan H, Sauerbrey A, Miyachi H, Chitambar CR. The anti-malarial artesunate is also active against cancer. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:767–773. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho WE, Peh HY, Chan TK, Wong WS. Artemisinins: pharmacological actions beyond anti-malarial. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:126–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park SJ, Choi CY, Jeong JC, Lee RK, Hwang YP. Artemisia annua extract ameliorates high-fat diet-induced fatty liver by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biomed Transl Res. 2020;21:59–71. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim KE, Ko KH, Heo RW, Yi CO, Shin HJ, Kim JY, Park JH, Nam S, Kim H, Roh GS. Artemisia annua leaf extract attenuates hepatic steatosis and inflammation in high-fat diet-fed mice. J Med Food. 2016;19:290–299. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2015.3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baek HK, Shim H, Lim H, Shim M, Kim CK, Park SK, Lee YS, Song KD, Kim SJ, Yi SS. Anti-adipogenic effect of Artemisia annua in diet-induced-obesity mice model. J Vet Sci. 2015;16:389–396. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2015.16.4.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park CY, Choi E, Yang HJ, Ho SH, Park SJ, Park KM, Kim SH. Efficacy of Artemisia annua L. extract for recovery of acute liver failure. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8:3738–3749. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murali AR, Carey WD. Liver test interpretation - Approach to the patient with liver disease: a guide to commonly used liver tests. Lyndhurst (OH): Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Center for Continuing Education; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz JE, Jandorf L, Krupp LB. The measurement of fatigue: a new instrument. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:753–762. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90104-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cathébras PJ, Robbins JM, Kirmayer LJ, Hayton BC. Fatigue in primary care: prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity, illness behavior, and outcome. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:276–286. doi: 10.1007/BF02598083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang SJ. Standardization of collection and measurement of health statistics data. Seoul: Korean Society for Preventive Medicine; 1993. Chapter 5. Stress. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang SJ, Koh SB, Kang MG, Hyun SJ, Cha BS, Park JK, Park JH, Kim SA, Kang DM, Chang SS, Lee KJ, Ha EH, Ha M, Woo JM, Cho JJ, Kim HS, Park JS. Correlates of self-rated fatigue in Korean employees. J Prev Med Public Health. 2005;38:71–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Reduction rate of AST.

Reduction rate of ALT.