Abstract

Food waste prevention and reduction are an economic, social and environmental concern included among the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) within Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. The third target under SDG 12 (Target 12.3) on Responsible Production and Consumption aims to halve food waste by 2030 at retail and consumer levels, considering that more than half of its quantity is generated by final consumers, both indoor and outdoor. However, the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak at the beginning of 2020 imposed several food consumption behaviors and lifestyle changes: food service facilities (e.g., restaurants, pubs, cafés, hotels, resorts) have been closed roughly all over the world, generating a sharp domestic consumption and an expected increase in household waste. The authors conducted an explorative research through the food diary approach. The purpose of this paper is to have a better understanding of household food consumption and wastage trends during Covid-19 pandemic testing, as well as food diary methodology strengths and weaknesses. Food diaries, even with their intrinsic limitations and biases, represent a valuable technique to obtain detailed qualitative and quantitative knowledge on daily food consumption and consumers’ behavior. Through the limited but significant results achieved, the authors highlight the logistics of the methodology and the food waste generation trends among a small sample of Italian families during the Covid-19 pandemic. Further, healthier work–life balances, adequate time management and smart food delivery seem to be good opportunities for food waste reduction in households.

Keywords: Food waste, Food diaries, Food waste behavior, Sustainability, COVID-19 pandemic

Introduction

Food waste has negative economic, social and environmental impacts, and its importance has increased over the last years (Hall et al. 2009; Gustavsson et al. 2011; Corrado et al. 2019), and it was included in 2015 among the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the United Nations (United Nations 2015, 2020; Roversi et al. 2020). Among them, the main challenges are related to Goal 2 “Zero Hunger” and Goal 12 “Responsible Consumption and Production,” with reference to Target 12.3, which requires, by 2030, to “halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses.” Furthermore, to accelerate the achievement of these SDGs, the European Commission (2015) has launched the “Closing the loop - An EU action plan for the Circular Economy,” implemented with the introduction of a monitoring framework for the circular economy (European Commission 2018). To achieve food system sustainability, as well as measure and compare progress toward more circular models among member states, the monitoring framework has set ten indicators grouped within four stages: production and consumption, waste, secondary raw materials and competitiveness and innovation, including food waste within the first group (production and consumption) (Eurostat 2020).

Worldwide, yearly food waste quantity is nearly 1.3 billion tons (International Food Policy Institute 2019; FAO 2019), equal to roughly one-third of global food production. In the European Union, more than 85 million tons (Mt) of food are thrown away each year: approximately 9 Mt at the agricultural stage, 17 Mt at processing, 4 Mt at retail and more than 55 Mt at food service (10 Mt) and household (45 Mt) (Møller et al. 2014; FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO 2018; McCarthy et al. 2018). In Italy, approximately 9 Mt of food are wasted yearly, corresponding to over 150 kg/capita (European Commission 2010; Notarfonso et al. 2015). Considering its associated financial costs, more than 140 billion euro are wasted each year in the European Union (Barrett 2010; FUSIONS 2016a, b), whereas greenhouse gas emissions have been estimated in approximately 170 Mt of CO2 (3% of global European Union emissions) (Monier et al. 2010; Philippidis et al. 2019).

Several studies have focused on food waste measurement, trying to quantify and qualify food waste along the whole food supply chain, from cradle to grave. Some authors have investigated its amount and the main drivers at the final consumption stage (Secondi et al. 2015; Fiore et al. 2017; Boschini et al. 2018) but fewer at agricultural (Schneider et al. 2019), processing (Thamagasorn and Pharino 2019) and retail stages (Caldeira et al. 2019). Moreover, according to measurement methodologies proposed by the European Commission (2019), the highest number of authors applied direct measurement (Elimelech et al. 2019), interviews and questionnaire approaches (Lanfranchi et al. 2016; Delley and Brunner 2018). However, only a few (Leverenz et al. 2019; Quested et al. 2020) have applied the food diary approach in households.

The Covid-19 pandemic, among other health and social challenges, has dangerously affected the economy and all industrial sectors, from agriculture to food manufacturing, impacting household food consumption to high degrees. According to the World Health Organization (2020), on 7 June 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in approximately 6.8 million confirmed cases and over 397,000 deaths globally. In Europe, more than 2.2 million cases and over 183,000 deaths have been confirmed, including more than 10% of cases and roughly 18% of deaths in Italy. Its socioeconomic impacts, mainly due to social distancing, self-isolation and travel restrictions, resulted in the entire lockdown of countries, millions of jobs being lost or converted to smart working and industrial plants, and schools, university and food service activities (e.g., hotels, canteens, restaurants) being closed to the public, with the only option of delivery or takeaway (Nicola et al. 2020; Shaw et al. 2020). The main consequences have been massive surpluses of highly perishable items at the agricultural stage (FAO 2020a, b; National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition 2020), disruptions (disconnections) in the food chain, impressive increases in food purchased in large-scale distributions (GDO) due to the “stock-effect” and “I-stay-at-home-effect” (Coldiretti 2020; Nielsen 2020a, b) and an expected sharp increase in food waste along the whole food supply chain, from the agricultural to consumption stages (World Economic Forum 2020). Since the highest amount of food waste is generated in households (Møller et al. 2014), the increase in domestic food consumption has inevitably spilled over into waste generation, including food waste. Thus, considering changes in people’s lifestyle and food consumption behaviors due to the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak at the beginning of March 2020, the authors conducted an explorative research though the food diary approach. The purpose is to gain a better understanding of household food consumption and wastage trends during Covid-19 pandemic testing, as well as the methodology strengths and weaknesses of the food diary. Through the limited but significant results achieved, the authors highlight the logistics of the methodology and the food waste generation trends among a small sample of Italian families during the Covid-19 pandemic.

To this extent, the main research questions investigated within this paper include the following: a) Are food diaries a reliable tool to measure household food waste; b) how have food consumption and food waste been characterized during the Covid-19 pandemic according to the sample; and c) which research directions should be investigated in the field of household food waste after the Covid-19 pandemic?

Methodology

Definitions and boundaries of the analysis

As stated by the legislative framework, Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on waste (OJEU 2018) defines food waste by referring to Article 2 of Regulation (EC) 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council (OJEU 2002). According to the definition of food, which includes “any substance or product, whether processed, partially processed or unprocessed, intended to be, or reasonably expected to be ingested by humans,” food waste is everything that has become waste. However, the literature does not give a clear definition of the issue. For instance, FAO (2011) described food waste as “the masses of food lost or wasted in the part of food chains leading to edible products going to human consumption,” distinguishing those occurring at the agricultural, industrial processing and retail stages (food losses) from those at the final consumption stage (food waste), whereas other reports and academic literature (Beretta et al. 2013; FUSIONS 2016a, b) made no distinction. As reported by FUSIONS (2016a, b), food waste is represented by “fractions of food and inedible parts of food removed from the food supply chain to be recovered or disposed.” According to (Quested and Johnson 2009; Beretta et al. (2013), to investigate the drivers for food waste and possible strategies toward its reduction, the authors distinguish between avoidable (food still edible by humans), potentially avoidable (food that some people eat and others do not) and unavoidable (inedible food) food waste. Moreover, in line with the scope of the analysis, in the following sections, the authors refer to food consumption as the whole food purchased by participants (global input at the beginning of consumption stage) and food waste (output of food intended for disposal). The difference between food consumption and food waste represents food intake. Then, only food waste occurring at final consumption at home is taken into account, not considering the losses from the agricultural to retail stages.

Food diary method: background and conceptual framework

Among the five main methodologies listed in the Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2019/1597 of 3 May 2019 (OJEU 2019), food diaries (sometimes called “kitchen diaries”) refer to individuals or groups of individuals (e.g., families, cohabitants) asked to measure and self-report food waste occurring in their daily lives (FUSIONS 2014), including the quality and quantity of discarded food, the waste generation step (e.g., preparation, leftovers), the main reasons for discarding it and its disposal route (e.g., kitchen bin, home compost) (Quested et al. 2020). In the past, social research mainly applied diaries in health and social science information, and they were later utilized to collect and evaluate quantitative and qualitative data in several disciplines (Jacelon and Imperio 2005; Reid et al. 2011). In general, its spread is mainly due to its proper capacity to limit observer influence and to record situations not accessible to the researcher, showing how and why participants assume certain behaviors (Elliott 1997; Sheble and Wildemuth 2009; Reid et al. 2011).

In the last decade (2010–2020), food diaries have been successfully applied in several studies all over the world (Silvennoinen et al. 2014; Jörissen et al. 2015), representing a useful tool in food waste research even with the limitations (Langley et al. 2010; Richter and Bokelmann 2017). For instance, through food diaries, Ilakovac et al. (2020) investigated the main differences in food waste production relative to the sociodemographic characteristics of household members, whereas Leverenz et al. (2019) tried to encourage their use and further development by comparing results before and after food diary experiences. Furthermore, some authors have analyzed the reliability of food diary results through combined approaches: van Dooren et al. (2019) mixed three self-assessments via household waste, sink/toilet and other sources in Dutch households, whereas Giordano et al. (2018) appealed to food diaries and questionnaires among Italian households. Other studies have measured food waste with food diaries: Katajajuuri et al. (2014), Silvennoinen et al. (2014) and van Herpen et al. (2019).

Data collection and food diary characteristics

Households have been recruited online from 11 March until 3 May 2020, according to the Italian Decree “#IoRestoaCasa,” which extended to the whole national territory’s previous provisions (Decree of 8 March 2020) in closing commercial, educational and food service activities and prohibiting public gatherings and private meetings (Governo Italiano 2020). The online-based food diary, created first with Microsoft Excel spreadsheet software and subsequently uploaded on Google Sheets, could be easily downloaded by each voluntary participant. The survey link was disseminated through social media channels (e.g., Facebook, Instagram).

Fifteen Italian households carried out the explorative study (28 people globally). Participants remained anonymous from the reception of the diary to the moment of delivery, even during coaching, and received no money for their participation. Anonymous participants were asked to complete a self-reporting period of seven days, beginning from Monday to Sunday (ordinary week), and received each time the needed information and online coaching to complete the sheets. The food dairy, realized in a tabular shape, was composed by nine sheets. The first one requested participant socio-demographic information (age, gender, residence, civil status, education and job description) and contained preliminary rules to complete the diary, as well as the consent to data processing only for the purpose of the analysis. The second sheet, with the aim of avoiding mistakes during compilation, contained a short guide and a complete daily example, but core parts of the food diary were the last seven sheets, one for each day.

Participants were asked to record, for each daily meal (breakfast, lunch, snack, dinner and extra meals), all food in terms of input (quality and quantity) and output (quality and quantity) in grams. No beverages and drinks, such as water, wine, beer, juices, coffees and teas, had to be recorded except for milk consumption/waste (Leverenz et al. 2019). To strengthen data quality regarding food waste and to avoid over- or undervaluation problems due to people’s memory or individuals’ approximation, the authors stressed that participants should weigh food waste with a kitchen scale (digital or analog) and report data on sheets every time food waste occurred (WRAP 2014; Istat 2011). Moreover, focusing on qualitative data, participants were asked to indicate – with a few keywords – the moment of waste generation (e.g., during storage, before cooking, during preparation), causes of wasting food (e.g., out-of-date, over-preparation) and disposal procedures (e.g., unsorted or separate collection, compost).

Data analysis

The first step of the explorative research was to analyze quantitative data. All quantitative data have been collected and catalogued using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet software, firstly distinguishing between the total grams of food consumed and total grams of food wasted, later divided per household and per capita. Subsequently, all quantities have been allocated within each food category considered (see Section 2.5). To analyze input (ingredients) and output (leftovers or waste) flows, the authors applied an input-output analysis based on the mass balance principle, connecting input materials to output flows in terms of mass, financial costs and nutritive factors (Brunner and Rechberger 2017; Zaghdaoui et al. 2017; Amicarelli et al. 2020). Lastly, since WRAP (2014) estimated that food waste recorded over a seven-day diary period tends to be 17% higher on the first day than the average of the other six remaining days, the authors applied an uncertainty of 15% to all mass variables from the second to the seventh day.

The second step regarded qualitative data. All information on the moment of waste generation, the causes of food waste and the disposal procedures, expressed in keywords, have been analyzed according to a qualitative content analysis (QCA) and then summarized in Table 5. All answers – read word by word in order to capture key thoughts or concepts on food consumption and food waste trends in households – “provided knowledge and understanding of the phenomenon under study” (Downe-Wamboldt 1992; Hsieh and Shannon 2005; Kasavan et al. 2019).

Table 5.

Drivers and strategies to reduce food waste at home

| Food waste drivers | Strategies to reduce waste | |

|---|---|---|

| Avoidable waste | Bad food storage | Food storage and food rotation are fundamental to avoid food waste. It is essential to place new products on the back and old ones ahead, practicing FIFO (first in, first out). |

| Lack in cooking skills and food control | Increase frequency of cooking, training of cooking skills and using kitchen devices for better food control are more likely to enhance skills. | |

| Lack of knowledge in households’ appliances (e.g., oven, stove) and oversights while cooking | Fridge, stove and oven functioning must be clear to avoid inedible preparations. For instance, fridge maintenance regards its temperature, which should be between 1 and 5 °C to preserve freshness and quality. | |

| Over purchase | Shopping planning enhances ingredients choice and meals organization, contributing to reduce over purchase, over cooking and leftovers generation. | |

| Potentially avoidable waste | Taste preferences | It could be useful to vary methods of preparations, be less delicate and give unappreciated food to other people. |

| Out of use-by | Food label comprehension should be improved. “Use-by” indicates that food is not safe anymore, while “best before” indicates that food quality has decreased (e.g., smell, taste, texture). | |

| Out of best-before-date | ||

| Unavoidable waste | Inedible parts (e.g., peel, bones, skins) | Quantities of unavoidable food waste cannot significantly be reduced. However, according to Mikami et al. (2012), it is possible to introduce the eco-cooking to reduce vegetable waste. |

| Unpredictable malfunctions of household’s appliances | N/A | |

Food categories, food prices and nutritive values

Food consumption and food waste, considering Gustavsson et al. (2011), Beretta et al. (2013) and other studies (Leverenz et al. 2019; Ilakovac et al. 2020), have been considered within eight main food categories (Table 1): fruits, vegetables, pasta and rice, meat and meat products, fish and fish products, milk and dairy products, bread and bakery products (also pastries) and prepared meals (both fresh and frozen).

Table 1.

Food categories included in the food diary

| Food category | Description |

|---|---|

| Fruits | Fruit peel, stone fruit, dried fruit shell, fruit leftovers, bad fruit (rotten fruit). |

| Vegetables and legumes | Vegetables peel and leftovers, external or inedible parts, rotten vegetables. |

| Pasta and rice | Pasta and tortillas leftovers, including also whole-wheat pasta and other typologies. |

| Meat and meat products | Meat leftovers, nerves, fats and bones, rotten meat, skins, meat with color, smell or taste altered. |

| Fish and fish products | Fish leftovers, bones and scales, fish with color, smell or taste altered. |

| Milk and dairy products | Leftovers or waste related to milk, yogurt, ice-creams, eggs, cheese and other products composed by milk as main ingredient. |

| Bread and bakery products | Leavened and unleavened, both sweet (cakes, pastries and biscuits) or salty, regardless of the preparation method. |

| Prepared meals | Prepared and semi-prepared meals (e.g. ready-to-eat chips, jam), including frozen products (e.g., salad, minestrone soup). |

(Source: Personal elaboration by the authors)

The authors, to evaluate food waste–associated financial costs (€), transformed mass values into monetary values based on average consumer prices mainly registered in February 2020 (Istat 2011; Ismea 2020; Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico 2020a, 2020b) and considering an average increase in food prices of +0.8% during the Covid-19 pandemic (Istat 2020a). Average consumer prices have been calculated considering the prices of consumer goods at marketplace or retail and their main price differences within four provincial capitals (Bari, Bologna, Rome and Milan). Furthermore, to calculate food waste–associated nutritional losses (MJ), the authors have considered average nutritional values in accordance with FAO’s (2020c) nutritive factors and Beretta et al. (2013). In particular, attention was given to the Italian basket of goods as reported by Istat (2020b), considering for each food category the five most preferred commodities by consumers (for instance, the fruit category contains oranges, tangerines, bananas, apples and pears). However, since a large variety of products included are within the “prepared meal” category, the authors have not calculated its associated financial costs and nutritional losses.

Results

Sample characteristics

Fifteen Italian households have carried out the explorative research, including 28 people globally. Table 2 illustrates the main sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (e.g., gender, age group, education) and indicates whether the participants were taking part in smart work. Mostly one-person (46%) and two-person households took part in the study, mainly composed by female (61%) and people aged between 19 and 29 years (53%). Single participants represented the majority of the sample (71%), whereas only a few (29%) got married. In terms of education, half of the participants had a master’s degree (50%). However, one of the starting points of the explorative research is related to the question “Are you working during Covid-19?” In addition, 100% of respondents stayed at home for the investigated period, of which 44% were not working since their activities have been stopped, 35% were smart working and 21% were studying at home. To this extent, all results and discussions should be read and interpreted.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

| Socio-demographic information | Households (n = 15) |

| Household size | 1 (= 46%) |

| 2 (= 33%) | |

| 3 (= 13%) | |

| 4 (= 8%) | |

| Socio-demographic information | Respondents (n = 28) |

| Gender | M (= 39%) |

| F (= 61%) | |

| Education | High school diploma (= 22%) |

| Bachelor’s degree (= 25%) | |

| Master’s degree (= 50%) | |

| Ph.D. or others (= 3%) | |

| Age group | 0–18 (= 4%) |

| 19–29 (= 53%) | |

| 30–45 (= 21%) | |

| 46–60 (= 18%) | |

| 60 or more (= 4%) | |

| Civil status | Single (= 71%) |

| Married (= 29%) | |

| Working during Covid-19? | Yes, at office (= 0%) |

| Yes, smart worker (= 35%) | |

| Yes, student at home (= 21%) | |

| No, not working (= 44%) |

(Source: Personal elaboration by the authors)

Even with all the limits imposed by the small sample size and in line with Langley et al. (2010) and Richter and Bokelmann’s (2017) research, the authors are conscious that achieved results are not representative of the Italian population and, consequently, of food waste in Italian households during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, they are significant to better understand trends, efforts and opportunities for future investigations that are larger and more targeted.

Food consumption and food waste

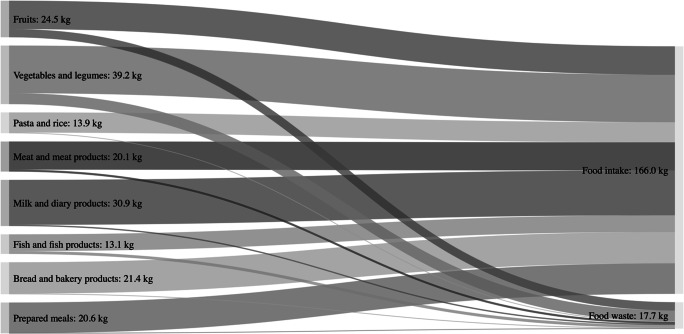

Figure 1 summarizes the results from food diaries, analyzed with a mass balance approach (input-output analysis). The Sankey diagram, in a visually effective and concise manner, illustrates food consumption (food intake + food waste) and food waste for all participants during the seven-day period, showing the quality and quantity of inputs purchased by households and related food intake, as well as food waste leaving the process. All quantities are expressed in kilograms (kg).

Fig. 1.

Sankey diagram for food consumption and food waste (kg) during Covid-19. (Source: Personal elaboration by the authors)

The highest percentage of food intake came from vegetables and legumes (19%), followed by milk and dairy products (18%) and bread and bakery products (13%). Consumption of pasta and rice (8%) and fish and fish products (7%) was relatively limited. The average weekly food consumption for respondents was approximately 6.56 kg of food, of which related food intake was 5.93 kg and food waste was 0.63 kg. Daily consumption was roughly 1 kg of food per respondent. On average, food waste represents approximately the 9.5% of global food consumption (Table 3), with several differences in the share of food waste among food categories: fruits (22%), vegetables and legumes (19%), fish and fish products (14%), meat and meat products (6%), milk and dairy products and pasta and rice (3%), bread and bakery products (2%) and prepared meals (1%).

Table 3.

Food consumption (kg) and food waste (kg) quantity

| Food consumption (food intake + food waste) | Mass (kg) |

| Total amount of food consumption per week for all respondents | 183.75 |

| Weekly amount of food consumption per household (average) | 12.25 |

| Daily amount of food consumption per household (average) | 1.75 |

| Average weekly amount of food consumption per respondent | 6.56 |

| Average daily amount of food consumption per respondent | 0.94 |

| Food waste | Mass (kg) |

| Total amount of food waste per week for all respondents | 17.68 |

| Weekly amount of food waste per household (average) | 1.17 |

| Daily amount of food waste per household (average) | 0.17 |

| Average weekly amount of food waste per respondent | 0.63 |

| Average daily amount of food waste per respondent | 0.09 |

| Percentage (%) | |

| Average daily percentage of food waste per category | 9.63 |

(Source: Personal elaboration by the authors)

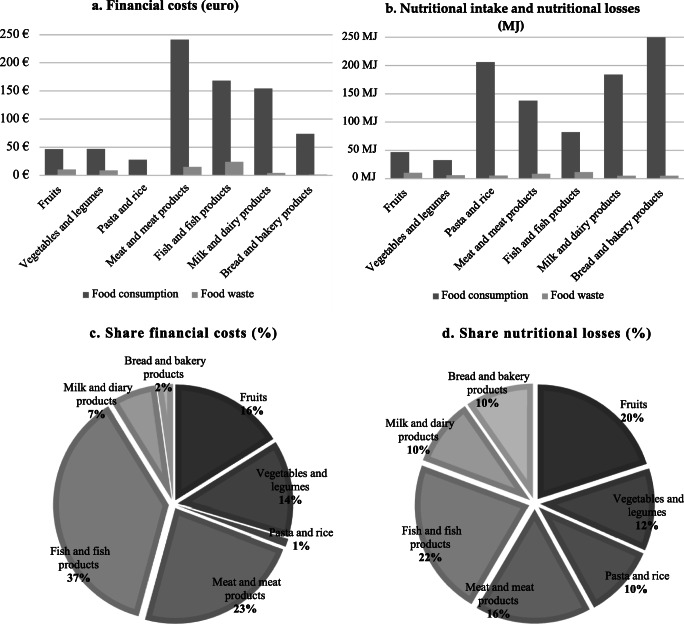

Financial costs and nutritional losses

In terms of financial costs and nutritional intake, Table 4 illustrates the following: a) food consumption– (purchase) and food waste–associated financial costs calculated to transform mass values into monetary values (see Section 2.3); and b) food consumption– (purchase) and food waste–associated nutritional values calculated according to Istat (2020b) and FAO (2020c) (see Section 2.3).

Table 4.

Food waste associated financial costs (€) and nutritional losses (MJ)

| Food categories | Food waste | Financial costs | Nutritional losses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kg | €/kg | Total € | MJ/kg | Total MJ | |

| a | b | (a x b) | c | (a x c) | |

| Fruits | 5.49 | 1.85–1.95 | 10.16–10.71 | 1.84–2.00 | 10.11–10.98 |

| Vegetables and legumes | 7.34 | 1.15–1.25 | 8.44–9.18 | 0.75–0.92 | 5.50–6.75 |

| Pasta and rice | 0.37 | 1.95–2.05 | 0.71–0.75 | 14.6–15.06 | 5.37–5.54 |

| Meat and meat products | 1.27 | 11.95–12.05 | 15.11–15.25 | 6.27–7.44 | 7.93–9.42 |

| Fish and fish products | 1.87 | 12.80–12.90 | 23.90–24.08 | 5.85–6.70 | 10.92–12.51 |

| Milk and dairy products | 0.85 | 4.95–5.05 | 4.22–4.30 | 5.64–6.27 | 4.81–5.35 |

| Bread and bakery products | 0.41 | 3.40–3.50 | 1.40–1.45 | 11.71–12.95 | 4.85–5.36 |

| Total | 17.68 | 63.97–65.83 | 49.50–55.91 | ||

(Source: Personal elaboration by the authors)

In Fig. 2, the histograms illustrate financial costs expressed in euros and nutritional intake/losses expressed in MJ, whereas pie charts record their share by food category in percentage.

Fig. 2.

a Food consumption and food waste associated financial costs (euro); b Food consumption and food waste associated nutritional intake and losses (MJ); c Share in food waste associated financial costs by food categories (%); d Share in food waste associated nutritional losses by food categories (%). (Source: Personal elaboration by the authors)

The whole sample’s financial weekly costs associated with food consumption have been approximately €760, which means nearly €50 per household and roughly €28 per respondent, recording meat and meat products’ highest share of purchase (32%), followed by fish and fish products (22%) because of their high prices in this research frame (12.80–12.90 €/kg and 11.95–12.05 €/kg, respectively). Furthermore, the total financial costs associated with food waste have been estimated to be approximately €65 (roughly 9%), which means approximately €5 per household and less than €2.5 per respondent per week, of which more than 37% are related to fish and fish products and roughly 23% to meat and meat products. However, even fruits (16%) and vegetables and legumes (14%) have largely contributed to the amount of financial costs.

In terms of nutritional value, Fig. 2 and Table 4 illustrate the food consumption and food waste nutritional intake balance expressed in MJ. The whole sample’s weekly nutritional values associated with food consumption were about 950 MJ, thus 65 MJ per household and roughly 33 MJ per respondent. Estimated nutritional losses have been 53 MJ (approximately 6% of food consumption) for the whole sample, which means about 3.5 MJ per households and less than 2 MJ per person per week. The highest percentage of nutritional losses has been recorded in fruits (20%).

Discussions

Food consumption and food waste trends before and during the Covid-19 pandemic

In the light of these results and considering that possible effects on food availability during the Covid-19 pandemic have been difficult to predict, the following key thoughts and concepts can be discussed.

Before conducting the explorative research, the authors believed that limitations in food distribution or even a lack in food accessibility would have caused severe societal consequences all over the world, even increasing food waste at the household level to higher rates (World Economic Forum 2020). Moreover, considering that all outdoor food service facilities have been closed (e.g., companies and school canteens, leisure and hospitality facilities), all grocery shopping opportunities have been limited and millions of people have been forced to stay at home, the authors would have expected an additional sharp increase in food waste at final consumption due to sudden changes in food habits and related negative emotions (Russell et al. 2017; Perez-Fuentes et al. 2020). These considerations on food waste increase have been essentially based and summarized in the so-called “stock-effect” – mainly due to the fear of not finding food in the medium to long term – and in the “I-stay-at-home-effect” (Nielsen 2020a). Further considerations were based on the fact that, at the distribution stage and during the first weeks of lockdown (17/02/2020–29/03/2020), higher values of purchased food have been registered in Italy (+12.5%) compared to those recorded in the same period of 2019. According to Nielsen (2020b), highest values have been registered in Southern Italy (+15.5%), followed by Central and Northern Italy (approximately +9.50%). Moreover, several reports all over the world (National Geographic, 2020) have stated that people are cooking more at home, thus producing more tonnages of food waste than usual.

However, reading sample results in the light of previous studies conducted with food diaries in households in Europe (Silvennoinen et al. 2014; Jörissen et al. 2015; Ilakovac et al. 2020), even with limitations due to the small sample size (Langley et al. 2010; Richter and Bokelmann 2017), the authors have detected a kind of counterbalanced effect, which has helped to better understand if and how a reduction in food waste coefficients and mass values has occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic.

For instance, Ilakovac et al. (2020) estimated an average amount of food waste per respondent per day of approximately 0.21 kg in Croatia, whereas Silvennoinen et al. (2014) assessed a value of roughly 0.41 kg in Finland. German results have been quite lower, being estimated in less than 0.14 kg per person, whereas Italian ones (0.13 kg) have been the lowest recorded in the literature (Jörissen et al. 2015). The highest average coefficients of food waste per food category have been recorded for vegetables (19%), milk and dairy products (17%) and bread and bakery products (13%), with an average daily coefficient in the range of 10–12% (Silvennoinen et al. 2014; Ilakovac et al. 2020). Results from this explorative paper, on the contrary, have recorded decreasing average tendencies, assessing an amount of food waste per person per day of approximately 0.09 kg (−30% on Italian literature values) (Jörissen et al. 2015) and an average food waste coefficient of roughly 9.5%.

The authors, according to the hypothesis of a counterbalanced effect during the Covid-19 pandemic, tried to explain the issue. Previous studies on the main drivers of food waste (Aschemann-Witzel et al. 2015; Boschini et al. 2020; Özbük and Coşkun 2020) have identified in bad food purchase planning (inaccurate forecasting) and bad inventory management, expired food and/or food with altered organoleptic characteristics during storage, overcooking, lack of cooking skills and lack of time, the major causes for food wastage. Such causes, although they seem different from each other, are mainly caused by stress and an unhealthy work–life balance, inadequate time management (e.g., which does not allow people to learn how to cook, for example) and, more generally, drastic changes in familial lifestyles that have occurred in recent years (Russell et al. 2017; Savarelli et al. 2019).

On the contrary, the lockdown forced people to stay at home, leading to an unexpected and opposite process compared to the aforementioned social trend: people had enough time to learn and/or improve food planning and storage operations, select a favorite food program (diet), enlarge time allotted for eating, progress in their cooking skills and familiarize themselves with domestic appliances (e.g., refrigerator, oven). Furthermore, not to be underestimated is the stock-effect, which hypothetically leads to greater awareness about food waste. Basically, the fear of reduced medium- to long-term food availability should lead consumers to preserve resources and manage them in a more sustainable way, consequently reducing food waste.

In such a context, as a natural consequence of the lockdown, an intense change in food management has been registered, with reference to smart food delivery (Jribi et al. 2020; Laguna et al. 2020; Patrinley et al. 2020). The role of food delivery, through digital apps (e.g., Just Eat, Glovo, Deliveroo) and technological or social tools (e.g., Telegram, Facebook), has been crucial to improve food purchase planning and increase the amount of time designated for choosing foods. Food delivery, as stated by the referenced literature (Park and Kim 2003; Kedah et al. 2015) and suggested by the sample, increased customers’ awareness on products (across high-definition colors, shapes and photographs) and improved buying decisions, thus reducing the occurrence of unappreciated and disposed meals in households.

However, the food diary participants still highlighted several causes of food waste. In line with previous studies (Salhofer et al. 2008; Beretta et al. 2013; Bernstad Saraiva Schott and Cánovas 2015; Schanes et al. 2018), the analysis revealed that quantities of unavoidable food waste (inedible food such as bones, skins and scraps) cannot significantly be reduced but that impressive efforts could be done to minimize avoidable and potentially avoidable fractions. Table 5 records the main reasons for food waste generation extrapolated by the sample and proposes possible strategies toward its reduction according to the referenced literature.

As the participants stated, the highest amount of food waste is represented by unavoidable waste, occurring almost always during food preparations (e.g., skins and scraps of fruit and vegetables, egg peel). Only a few preparations, on the contrary, have been discarded according to limited cooking skills (e.g., completely burnt bread), bad food storage (e.g., overextended storage of eggplants or strawberries) and taste preferences (e.g., pasta with onions or mushrooms). According to participants’ notes, overcooking problems (e.g., portions and meals that are too large) have hardly been noticed, confirming that the lockdown has improved shopping planning, food control and leftover reuse.

Limitations and future directions

Although the food diary participants seemed very enthusiastic over the course of the accounting period (Langley et al. 2010; Sharp et al. 2010), its usage presents relevant difficulties and some disadvantages. First, the authors found it difficult to recruit households, and dropout rates were high during the experiment period. Furthermore, as already stated by FUSIONS (2014) and van Herpen et al. (2016), the authors went through the potential risks of self-selection (i.e., only interested people participated in the experiment) and poor data quality due to approximation or undervaluation. Another obstacle, which excluded the majority of aged people from sample selection (60 or more years old), was the online-based food diary. However, several participants wondered if an internet or mobile app was available to complete the food diary more precisely.

Further limitations related to food diaries, as already stated by other studies (Høj 2011; FLW Protocol 2016; Quested et al. 2020), regard consumer behavior reactivity, a lack of reporting, accounting and selection biases. For instance, to adopt a more “socially acceptable” behavior during the accounting period, participants could eat differently than normal or dispose of food in a more sustainable way. Moreover, diary keepers are usually not aware of all the food being disposed of at home by other household members or are confused about what should be accounted for, thus understating the amount of food waste. Lastly, as already stated in terms of self-reporting risk, people who participate in the experiment are usually not representative of the whole population, since it is expected that some participants are more interested in food waste issues than others, and adjustments in such direction are extremely difficult and aleatory.

Nevertheless, food diaries still represent a valuable tool to improve knowledge on food waste trends and collect objective quantitative (e.g., mass value, financial costs and nutritional values) and qualitative data (e.g., causes of food waste, disposal procedures). Based on the pre-Covid-19 food waste literature data (FAO 2017, 2018, 2019; Caldeira et al. 2019), each year more than 1.3 billion tons of food are globally thrown away along the whole food supply chain, equal to 5200 MJ and approximately 2145 billion euro. This means that, each week, each person wastes less than 1.8 kg, corresponding to 7 MJ and more than 2.9 euro only at final consumption. Trends observed by this explorative research have demonstrated a sharp decrease in terms of mass, nutritional intake and financial costs, confirming the previous hypothesis of a counterbalanced effect. The identified causes could represent the key variables for further research, in order to develop food waste minimization strategies and achieve the 2030 SDGs.

Moreover, future directions of the analysis should focus on the role of smart food delivery toward food waste reduction with regard to its opportunities to enlarge customers’ awareness on products and improve buying decisions. As exposed in the explorative research, it could be interesting to analyze how to switch from an unhealthy work–life balance and inadequate time management toward a heathier and more adequate one. The role of time management toward food management sustainability is crucial, and time availability could improve food planning and storage operations, the selection of favorite food programs, cooking skills and, not least important, familiarity with domestic appliances.

Conclusion

Food diaries are a useful instrument to provide a better understanding of household food consumption and wastage during the Covid-19 pandemic. One of the main hypotheses from the presented explorative research, and in line with the few studies conducted on food waste in Italy in times of economic crisis (Fanelli and Di Florio 2016), is that food consumption and food waste behaviors have been more virtuous, showing that the Covid-19 pandemic has enhanced people’s attitude toward food waste reduction and more sustainable consumption models (Galanakis 2020; Jribi et al. 2020). Moreover, it has been shown that effects, such as stock-effect and I-stay-at-home-effect, positively influenced food waste reduction. Indeed, decreasing trends in terms of mass, nutritional intake and financial costs have been detected. During the Covid-19 lockdown, as shown by participants in the explorative research, people had adequate time to improve food planning and storage operations, select food programs, enlarge time allotted for eating, optimize all ingredients and leftovers, familiarize themselves with domestic appliances and avoid panic about food availability.

The authors are convinced that food diaries, even with some limitations related to difficult recruitment, risks of self-selection and high dropout rates, could contribute to increased qualitative and quantitative knowledge on food waste issues (e.g., mass value, financial costs and nutritional values), especially considering the lack of information regarding the Covid-19 pandemic behavior. However, further studies will investigate food waste behaviors and social attitude/responsibility at a large scale in an attempt to complete food waste measurement with more detailed and reliable data. In addition, the authors believe it is essential to investigate further the role of smart food delivery and time management toward food waste reduction.

Lastly, because the Covid-19 pandemic is one of the worst economic, social and environmental crises after the Second World War, it could represent the real watershed that people were expecting, highlighting the importance of a robust and resilient food system that functions in all circumstances and that aligns people’s health, ecosystems, supply chains, consumption patterns and environmental boundaries (European Commission 2020; Roversi et al. 2020). By taking advantage of such a disaster, awareness on previous unsustainable behavior could increase, thus enhancing awareness about the food waste issue, both at the industrial and household levels. Sustainability starts with the individuals, not only at the farm or processing levels but also at the domestic consumption stage.

Biographies

Vera Amicarelli

, Ph.D. in Commodity Science, is Associate Professor at Department of Economics, Management and Business Law DEMDI Commodities Science section at the University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy. She teaches Industrial Ecology, Quality theory and technique and Resource and waste management. She is author of more than 75 papers published on scientific journals and academic volumes. Her current research interests are focused on: Material Flow Analysis, Environmental Indicators such as Water and Carbon Footprint and Circular Economy. Her main academic activities are related to: Erasmus+ exchange program - she is department delegate and coordinator for several agreements with foreign universities - and she is in the working group for DEMDI course of study qualification. Since 2018 she is member of ICESP (Italian Circular Economy Stakeholders Platform) and form 1998 of Italian Commodity Science Academy (AISME).

Christian Bux

is a Ph.D. student in Economics and Management at University of Bari Aldo Moro, Department of Economics, Management and Business Law. His main field of interest is the relationship between natural resources, commodity production/consumption and environmental management systems. His doctoral research project regards food loss and waste management, Circular Economy and Material Flow Analysis. Christian Bux is corresponding author (christian.bux@uniba.it).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Vera Amicarelli, Email: vera.amicarelli@uniba.it.

Christian Bux, Email: christian.bux@uniba.it.

References

- Amicarelli, V., Bux, C., & Lagioia, G. (2019). Food consumption behavior towards food waste minimization among university students. In: Proceedings of 5th Scientific International Conference on Environmental Crimes, Environmental Safety and National Security. Tirana, Albania, 30 July 2019. Tirana: Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

- Amicarelli, V., Bux, C., & Lagioia, G. (2020). How to measure food loss and waste? A material flow analysis application. British Food Journal, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print, .

- Aschemann-Witzel J, de Hooge I, Amani P, Bech-Larsen T, Oostindjer M. Consumer-related food waste: causes and potential for action. Sustainability. 2015;7(6):6457–6477. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett B. Measuring food insecurity. Science. 2010;327:825–827. doi: 10.1126/science.1182768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta C, Stoessel F, Baier U, Hellweg S. Quantifying food losses and the potential for reduction in Switzerland. Waste Management. 2013;33:764–773. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstad Saraiva Schott A, Cánovas A. Current practice, challenges and potential methodological improvements in environmental evaluations of food waste prevention – a discussion paper. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2015;101:132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Boschini M, Falasconi L, Giordano C, Alboni F. Food waste in school canteens: a reference methodology for large-scale studies. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2018;182:1024–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Boschini M, Falasconi L, Cicatiello C, Franco S. Why the waste? A large-scale study on the causes of food waste at school canteens. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2020;246:118994. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner PH, Rechberger H. For environmental, resource and waste engineers. 2. Boca Raton, London, New York: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2017. Handbook of material flow analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira C, De Laurentiis V, Corrado S, van Holsteijn F, Sala S. Quantification of food waste per product group along the food supply chain in the European Union: a mass flow analysis. Resources, Conservation, and Recycling. 2019;149:479–488. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldiretti (2020). Coronavirus, balzo nell’acquisto di prodotti alimentari. https://www.coldiretti.it/economia/coronavirus-balzo-nellacquisto-di-prodotti-alimentari. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- Corrado S, Caldeira C, Eriksson M, Hanssen OJ, Hauser H-W, van Holsteijn F, Liu G, Ostergren K, Parry K, Parry A, Secondi L, Stenmarck A, Sala S. Food waste accounting methodologies: challenges, opportunities, and further advancements. Global Food Security. 2019;20:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delley M, Brunner T. Household food waste quantification: comparison of two methods. British Food Journal. 2018;120:1504–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care for Women International. 1992;13:313–321. doi: 10.1080/07399339209516006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elimelech E, Ert E, Ayalon O. Bridging the gap between self-assessments and measured household food waste: a hybrid valuation approach. Waste Management. 2019;95:259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott H. The use of diaries in sociological research on health experience. Sociological Research Online. 1997;2(2):38–48. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (2010). Preparatory study on food waste across EU27. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/eussd/pdf/bio_foodwaste_report.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- European Commission (2015). Closing the loop - An EU action plan for the Circular Economy. https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/com-2015-0614-final. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- European Commission. (2018). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a monitoring framework for the circular economy. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/circular-economy/pdf/monitoring-framework.pdf. Accessed on 13 May 2020.

- European Commission (2019). Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2019/1597 of 3 May 2019. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2019:248:TOC. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- European Commission (2020). Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the Regions. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0381&from=EN. Accessed 28 May 2020.

- Eurostat (2020). Monitoring framework. Circular Economy Indicators. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/circular-economy/indicators/monitoring-framework. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- Fanelli, R.M., & Di Florio, A. (2016). Domestic food waste, gap in times of crisis, 52ndSIDEA Annual Conference, Roma-Viterbo, 17th–19th September 2015. Firenze University Presss.

- FAO . Global food losses and food waste: Extent, causes and prevention. FAO: Rome; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . Global initiative on food loss and waste. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2018). World food and agriculture – Statistical pocketbook 2018, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States, Rome.

- FAO (2019). The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, Rome, Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- FAO (2020a). Novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Q&A: CODIV-19 pandemic – impact on food and agriculture. http://www.fao.org/2019-ncov/q-and-a/impact-on-food-and-agriculture/en/ Accessed 21 May 2020.

- FAO (2020b). During COVID-19 times: 9 tips to reduce food waste. http://www.fao.org/food-loss-reduction/news/detail/en/c/1267958/. Accessed 21 May 2020.

- FAO (2020c). Nutritive Factors. http://www.fao.org/economic/the-statistics-division-ess/publications-studies/publications/nutritive-factors/en/. Accessed 26 May 2020.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (2018). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2018. Building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States, Rome.

- Fiore M, Pellegrini G, La Sala P, Conte A, Liu B. Attitude toward food waste reduction: The case of Italian consumers. International Journal of Globalisation and Small Business. 2017;9:185–201. [Google Scholar]

- FLW Protocol (2016). Guidance on FLW Quantification Methods. http://flwprotocol.org/. Accessed 11 May 2020.

- FUSIONS (2014). Report on review of (food) waste reporting methodology and practice. Full report. http://www.eu-fusions.org/index.php/publications/266-establishing-reliable-data-on-food-waste-and-harmonising-quantification-methods.pdf. .

- FUSIONS (2016a). Estimates of European food waste levels. https://www.eu-fusions.org/phocadownload/Publications/Estimates%20of%20European%20food%20waste%20l evels.pdf. Accessed 08 May 2020.

- FUSIONS (2016b). Market-based instruments and other socio-economic incentives enhancing food waste preventing and reduction. https://www.eu-fusions.org/index.php/download?download%C2%BC%20219:d33a-market-based-instrument. Accessed 3 Mar 2020.

- Galanakis CM. The food Systems in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Foods. 2020;9:523. doi: 10.3390/foods9040523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano C, Piras S, Boschini M, Falasconi L. Are questionnaires a reliable method to measure food waste? A pilot study on Italian households. British Food Journal. 2018;120:2885–2897. [Google Scholar]

- Governo Italiano (2020). #IoRestoaCasa, misure per il contenimento e gestione dell’emergenza epidemiologica. http://www.governo.it/it/iorestoacasa-misure-governo. Accessed 08 May 2020.

- Gustavsson J, Cederberg C, Sonesson U, Van Otterdijk R, Meybeck A. Global food losses and food waste. Extent, causes and prevention. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hall KD, Guo J, Dore M, Chow CC. The progressive increase of food waste in America and its environmental impact. PLoS One. 2009;4:11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høj, S.B (2011). Metrics and measurement methods for the monitoring and evaluation of household food waste prevention interventions. Master Business thesis. Adelaide: University of South Australia.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilakovac B, Voca N, Pezo L, Cerjak M. Quantification and determination of household food waste and its relation to sociodemographic characteristics in Croatia. Waste Management. 2020;102:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Food Policy Research Institute (2019). 2019 global food policy report. International food policy research institute, Washington, DC. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/2019-global-food-policy-report. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- Ismea (2020). Latte e derivati bovini. http://www.ismeamercati.it/lattiero-caseari/latte-derivati-bovini. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- Istat (2011). L’Italia in 150 anni. Sommario di statistiche storiche 1861-2011, 2011, 867–899. https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/228440. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- Istat (2020a). Prezzi al consumo. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/241413. Accessed 08 May 2020.

- Istat (2020b). Indici dei prezzi al consumo – Anno 2020. Struttura gerarchica e paniere. https://www.istat.it/it/files//2020/02/Struttura-gerarchica-2020.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2020.

- Jacelon CS, Imperio K. Participant diaries as a source of data in research with older adults. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:991–997. doi: 10.1177/1049732305278603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörissen J, Priefer C, Bräutigam KR. Food waste generation at household level: results of a survey among employees of two European research centers in Italy and Germany. Sustainability. 2015;7(3):2695–2715. [Google Scholar]

- Jribi, S., Ismail, H.B., Doggui, D., & Debbabi, H. (2020). Covid-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on households food wastage? Environment, Development and Sustainability, Springer, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kasavan S, Mohamed SF, Halim SA. Drivers of food waste generation: Case study of island-based hotels in Langkawi, Malaysia. Waste Management. 2019;91:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katajajuuri JM, Silvennoinen K, Hartikainen H, Heikkilä L, Reinikainen A. Food waste in the Finnish food chain. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2014;73:322–329. [Google Scholar]

- Kedah, Z., Ismail, Y., Ahasanul, A., & Ahmed, S. (2015). Key success factors of online food ordering services: an empirical study. Malaysian Management Review, 50.

- Kremer S, Stijnen D. Consumption life cycle contributions – Assessment of practical methodologies for in- home waste measurement. Wageningen: Wageningen University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Laguna L, Fiszman S, Puerta P, Chaya C, Tàrrega A. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on food priorities. Results from a preliminary study using social media and an online survey with Spanish consumers. Food Quality and Preference. 2020;86:104028. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfranchi M, Calabrò G, De Pascale A, Fazio A, Giannetto C. Household food waste and eating behavior: empirical survey. British Food Journal. 2016;118(12):3059–3072. [Google Scholar]

- Langley J, Yoxall A, Heppell G, Rodriguez-Falcon E, Bradbury S, Lewis R, Luxmoore J, Hodzic A, Rowson J. Food for thought? - A UK pilot study testing a methodology for compositional domestic food waste analysis. Waste Management and Research. 2010;28(3):220–227. doi: 10.1177/0734242X08095348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverenz D, Moussawel S, Maurer C, Hafner G, Schneider F, Schmidt T, Kranert M. Quantifying the prevention potential of avoidable food waste in households using a self-reporting approach. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2019;150:104417. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy U, Ismail U, Badia-Melis R, Mercier S, O’Donnel CP, Ktenioudaki A. Global food security. Issues, challenges and technological solutions. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2018;77:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mikami A, Araki Y, Sasahara M, Ito K, Nagao K. Effects of eco-cooking methods on reducing vegetable waste. Journal of Cookery Science of Japan. 2012;45:3. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (2020a). Beni e servizi di largo consumo. http://osservaprezzi.mise.gov.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=22&Itemid=138 Accessed 08 May 2020.

- Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (2020b). Osservatorio prezzi e tariffe. Panoramica flash sull'andamento dei prezzi dei principali prodotti ortofrutticoli rilevati presso i mercati - Febbraio 2020. http://osservaprezzi.mise.gov.it/Analisi_mensili/Panoramica%20flash_feb20.pdf Accessed 15 May 2020.

- Møller H, Ole JH, Gustavsson J, Oestergren K, Stenmarck A. Report on review of (food) waste reporting methodology and practice. Norway: Ostfold Research; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Monier, V., Escalon, V., & O’Connor, C. (2010). Preparatory Study on Food Waste across EU 27. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/bio_foodwaste_report.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- National Geographic (2020). Food waste and food insecurity rising amid coronavirus pandemic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/03/food-waste-insecurity-rising-amid-coronavirus-panic/. Accessed 19 May 2020.

- National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (2020). Mitigating Immediate Harmful Impacts of COVID-19 on Farms and Ranches Selling through Local and Regional Food Markets. https://localfoodeconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2020_03_18EconomicImpactLocalFood.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha M, Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus and COVID-19 pandemic: a review. International Journal of Surgery. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen (2020a). Coronavirus: la spesa in quarantena. The NielsenCompany (US). https://www.nielsen.com/it/it/insights/article/2020/coronavirus-la-spesa-in-quarantena/ Accessed 19 May 2020.

- Nielsen (2020b). Insights. Largo consumo e distribuzione. The NielsenCompany (US) https://www.nielsen.com/it/it/insights/. Accessed 16 April 2020.

- Notarfonso, M., Coppola G., & Farina, S. (2015). Food recovery and waste reduction foodward project progetto sul recupero e la riduzione degli sprechi alimentari. http://www.federalimentare.it/informalimentare/informalimentare_6_2015-FOODWARDPROJECT.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- OJEU (Official Journal of the European Parliament) (2002). Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety, L. 31/1.

- OJEU (Official Journal of the European Parliament) (2018). Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste, L. 150/109.

- OJEU (Official Journal of the European Union) (2019). Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2019/1597 of 3 May 2019 supplementing Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards a common methodology and minimum quality requirements for the uniform measurement of levels of food waste, L.248/77.

- Özbük RMY, Coşkun A. Factors affecting food waste at the downstream entities of the supply chain: a critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2020;244:118628. [Google Scholar]

- Park CH, Kim YG. Identifying key factors affecting consumer purchase behavior in an online shopping context. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management. 2003;31(1):16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Patrinley JR, Berkowitz ST, Zakria D, Totten DJ, Kurtulus M, Drolet BC. Les- sons from operations management to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Medical Systems. 2020;44(7):129. doi: 10.1007/s10916-020-01595-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Fuentes MDC, Molero Jurado MDM, Martos Martinez A, Gazquez Linares JJ. Threat of COVID-19 and emotional state during quarantine: positive and negative affect as mediators in a cross-sectional study of the Spanish population. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0235305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippidis G, Sartori M, Ferrari E, M'Barek R. Waste not, want not: a bio-economic impact assessment of household food waste reductions in the EU. Resources Conservation and Recycling. 2019;146:514–522. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quested T, Johnson H. Household food and drink waste in the UK. Banbury, UK: Waste & Resources Action Programme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Quested TE, Griff Palmer L, Moreno C, McDermott C, Schumacher K. Comparing diaries and waste compositional analysis for measuring food waste in the home. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2020;262:121263. [Google Scholar]

- Reid L, Hunter C, Sutton PW. Rising to the challenge of environmental behavior change: developing a reflexive diary approach. Geoforum. 2011;42:720–730. [Google Scholar]

- Richter B, Bokelmann W. Explorative study about the analysis of storing, purchasing and wasting food by using household diaries. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2017;125:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Roversi, S., Laricchia, C., & Lombardi, M. (2020). Food for earth a toolbox to unleash the regenerative power of food: Energy for life adopting a prosperity-drive and life – Centered approach. FutureFoodInstitute.org.

- Russell SV, William Young C, Unsworth KL, Robinson C. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behaviour. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2017;125:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Salhofer S, Obersteiner G, Schneider F, Lebersorger S. Potentials for the prevention of municipal solid waste. Waste Management. 2008;28(2):245–259. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarelli E, Francioni B, Curina I. Healthy lifestyle and food waste behaviour. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2019;37(2):148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Schanes K, Dobernig K, Gözet B. Food waste matters – a systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2018;182:978–991. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F, Part F, Gobel C, Langen N, Gerhards C, Kraus GF, Ritter G. A methodological approach for the on-site quantification of food losses in primary production: Austrian and German case studies using the example of potato harvest. Waste Management. 2019;86:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secondi L, Principato L, Laureti T. Household food waste behaviour in EU-27 countries: a multilevel analysis. Food Policy. 2015;56:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp V, Giorgi S, Wilson DC. Methods to monitor and evaluate household waste prevention. Waste Management and Research. 2010;28(3):269–280. doi: 10.1177/0734242X10361508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw R, Kim Y, Hua J. Governance, technology and citizen behavior in pandemic: lessons from COVID-19 in East Asia. Progress in Disaster Science. 2020;6:100090. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheble L, Wildemuth B. Research diaries. In: Wildemuth B, editor. Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited; 2009. pp. 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Silvennoinen K, Katajajuuri J-M, Hartikainen H, Heikkilä L, Reinikainen A. Food waste volume and composition in Finnish households. British Food Journal. 2014;116(6):1058–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Thamagasorn M, Pharino C. An analysis of food waste from a flight catering business for sustainable food waste management: a case study of halal food production process. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2019;228:845–855. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2015). Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld.

- United Nations (2020). Obiettivo 2: Porre fine alla fame, raggiungere la sicurezza alimentare, migliorare la nutrizione e promuovere un’agricoltura sostenibile. https://unric.org/it/obiettivo-2-porre-fine-alla-fame-raggiungere-la-sicurezza-alimentare-migliorare-la-nutrizione-e-promuovere-unagricoltura-sostenibile/. .

- van Dooren C, Janmaat O, Snoek J, Schrijnen M. Measuring food waste in Dutch households: a synthesis of three studies. Waste Management. 2019;94:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Herpen E, van der Lans IA, Holthuysen N, Nijenhuis-de Vries M, Quested TE. Comparing wasted apples and oranges: an assessment of methods to measure household food waste. Waste Management. 2019;88:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum (2020). Here’s how COVID-19 creates food waste mountains that threaten the environment. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/covid-19-food-waste-mountains-environment/. Accessed 10 September 2020.

- World Health Organization (2020). Coronavirus desease (COVID-19). Situation Report – 139. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200607-covid-19-sitrep-139.pdf?sfvrsn=79dc6d08_2. Accessed 8 June 2020.

- WRAP (2014). Household food and drink waste: a product focus, 2014. http://www.wrap.org.uk/content/household-food-drink-waste-–-product-focus. .

- Zaghdaoui, H., Jaegler, A., Gondran, N., & Montoya-Torres, J. (2017), Material flow analysis to evaluate sustainability in supply chains. 20th World Congress the International Federation of Automatic Control, July 2017, Toulouse, France.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.