Abstract

Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN) is a rare and often fatal pathology of unclear etiology affecting the distal two-thirds of the esophagus. Typically, elderly patients with multiple comorbidities present with signs of upper gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage. On endoscopy, the mucosa is black due to ischemic necrosis, resulting in the commonly used term “black esophagus.” We present a rare case of a 61-year-old male presenting with shortness of breath and hematemesis diagnosed as AEN through endoscopy. This case illustrates the importance of considering AEN as part of differential diagnoses in a rising elderly population with multiple comorbidities that present with upper GI hemorrhage. Treatment should be aimed at maintaining hemodynamic stability with high-dose proton pump inhibitors.

Keywords: Black esophagus, endoscopy, esophageal necrosis, upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage

Introduction

Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN) is a rare disease characterized by a diffuse circumferential black appearance of the esophageal mucosa affecting the distal esophagus. It is found in patients with multiple or longstanding comorbidities such as diabetes, respiratory, or vascular diseases. Esophageal mucosa of the distal part of the esophagus is often associated with circumferential necrosis, from which the terminology “black esophagus” was coined.[1] Although the prevalence of AEN ranges from 0.001% to 0.2%, the mortality approaches 32%.[2] We present a rare case of a 61-year-old male who presented with hypoxia and hematemesis that was later determined to be secondary to AEN.

Case Report

A 61-year-old caucasian male presented with complaints of shortness of breath after accidental extrication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). The patient has a medical history of type II diabetes mellitus requiring insulin, hypothyroidism, and respiratory failure status post-tracheostomy collar. Six months before presentation, the patient had a perforated duodenal ulcer that was complicated with septic shock and a prolonged course on a ventilator requiring tracheostomy. He was appropriately treated with antibiotics, PEG placement for long-term support, and eventually discharged to a nursing home. His regular medications included levothyroxine, insulin, ipratropium-albuterol nebulizer, morphine, intralipid, clinimix/dextrose amino acid infusion, and scopolamine patch. At the nursing home, medical responders found his pulse oximetry to be 86% on ambient air, prompting them to provide a high fraction of supplemental oxygen through trach collar improving saturation to 94%. While en route to the hospital, he experienced three episodes of coffee-ground emesis. The patient denied any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use, cough, fever, hemoptysis, or hematemesis before presentation of the symptoms.

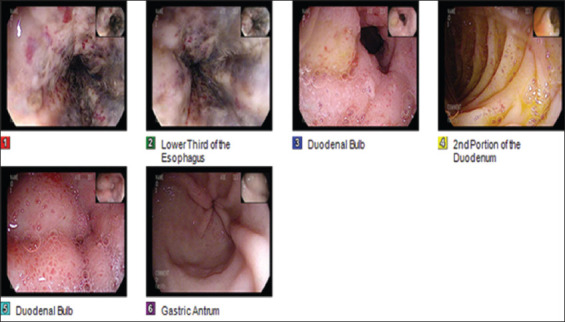

On arrival in ED, he was placed on supplemental oxygen through trach collar saturating 96–100%. He appeared frail, communicating in complete sentences. The patient’s vitals were as followed: Blood pressure 113/63 mm Hg, temperature 97.9 F, pulse 110 beats/min, and respiratory rate 22 breaths/min. Respiratory examination showed diminished breath sounds and inspiratory wheezing on the right lower base, and abdominal examination revealed non-distended, normal bowel sounds, and no stigmata of blood or secretions from patent PEG tube insertion site. Initial laboratory investigations revealed elevated blood urea nitrogen 54 mg/dl, creatinine 0.9 mg/dl, hemoglobin 10.9 g/dl, leukocytosis 29.4 × 103/mm3 with bandemia (11% of white blood count), hypoalbuminemia 2.4 g/dl, mildly elevated alanine aspartate (61 u/L), and INR 1.1. The patient had an X-ray revealing a possible air-bronchogram on the right lower lobe suggestive of pneumonia [Figure 1]. The patient was then started on intravenous hydration, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, and intravenous pantoprazole. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed severe esophagitis with diffuse dark mucosal discoloration, erosion, and profound ulceration in the entire esophagus suggestive of ischemic necrosis [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Portable chest x-ray: Showing hazy opacification of a portion of the right hemithorax with obliteration of the right hemidiaphragm and fluid extending up the lateral chest wall to almost cap the apex. Left hemidiaphragm is also somewhat hazy suggesting infiltrate and/or fluid

Figure 2.

Figure 1 shows the middle third of the esophagus with circumferential necrosis, darkening, and extending to the lower third of the esophagus shown in Figure 2

Despite the resolution of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding following EGD, the patient experienced an episode of hypoxia requiring intensive care monitoring. He subsequently experienced cardiac arrest resulting in untimely death despite resuscitative measures.

Discussion

AEN, also known as “black esophagus,” is a rare but deadly disease that is associated with a high morbidity and mortality. It was first described by Goldenberg et al. in 1990.[1] The prevalence of AEN ranges from 0.001% to 0.2%; however, the mortality approaches 32%.[2]

Although the pathophysiology continues to be poorly understood, its etiology is described as being multifactorial. It results from the combination of tissue hypoperfusion, impaired local defense barriers, and a massive influx of gastric contents, which weaken and damage the esophageal mucosa. The distal one-third of the esophagus is vulnerable to ischemia due to a relatively poor vascularity. Some of the risk factors identified, which include diabetes mellitus, malnourishment, atherosclerosis, renal insufficiency, and sepsis, all which may contribute to ischemia and tissue hypoperfusion.[3-8] In a prospective study performed by Soussan et al. for eight patients, three patients had diabetes mellitus, five patients had only involvement of the distal esophagus, and four patients died in <14 days.[9]

Patients with AEN are typically middle-aged or elderly males with significant medical comorbidities, who present to the hospital with signs of upper GI bleeding, such as hematemesis, coffee ground vomiting, and melena.[7] Patients also may present with epigastric or abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, low-grade fever, and non-specific physical examination findings. Most of the presentation is related to underlying comorbid conditions such as cachexia, pallor, abdominal tenderness, and guaiac positive stool. AEN can be asymptomatic and discovered during endoscopic interventions. Laboratory analysis may show leukocytosis and anemia, while computed tomography may reveal thickened distal esophagus, hiatal hernia, and a distended fluid-filled stomach with possible gastric outlet obstruction.[2,4]

The classical endoscopic appearance of AEN is a circumferential, black appearing, diffusely necrotic esophageal mucosa, preferentially affecting the distal esophagus, and stopping at the gastroesophageal junction.[3] The diagnosis is supported by brush cytology or biopsy, but they are not required for diagnosis; histological findings include the absence of viable epithelium, abundant necrotic debris, and necrotic changes of the mucosa, which may extend into the submucosa and muscularis propria.[2,3]

AEN is managed with intravenous proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or histamine type 2 receptor (H2) blockers until an improvement in clinical status is observed, after which patients can be switched to oral PPIs. Oral sucralfate may be used as adjuvant therapy. Empiric antibiotic therapy is indicated in suspected esophageal perforation, immunocompromised states, unexplained fevers, or rapid clinical deterioration. Antimicrobial therapy should then be adjusted according to esophageal cultures. Surgery is reserved for perforated esophagus with resultant mediastinitis or abscess formation.[2,3] Insertion of naso- or orogastric tubes should be avoided at all costs as the fragility of ischemic and necrosed mucosa may be complicated with perforation of the esophagus.[5]

In a study by Soussan et al., four of the eight patients died within 1–2 weeks and Grudell et al. reported 14 deaths of 47 patients, whose cause of death was not attributed to AEN and remained uncertain.[9,10] Similarly, in our case, the patient had no obvious signs or symptoms suggesting AEN before experiencing the cardiac arrest.

Conclusion

AEN demands a high level of caution due to high mortality and management should include supportive therapies that may maximize the perfusion of the esophagus, suppress acid section, and include treatment with antibiotics when indicated.

Author Declaration Statements

Patient’s consent

Patient’s informed written consent was taken for publishing the case in a scientific journal.

Availability of data and material

The data used in this study are available and will be provided by the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the revision and approval of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Michael Agnelli (Associate Program Director of the Internal Medicine Residency), Dr. Monisha Singhal (Associate Program Director of the Internal Medicine Residency), and Dr. Robert Lahita (Chairman of the Department of Medicine) for their continuous support and guidance.

References

- 1.Goldenberg SP, Wain SL, Marignani P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:493–6. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90844-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau S, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis:A rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurvits GE. Black esophagus:Acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3219–25. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i26.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burtally A, Gregoire P. Acute esophageal necrosis and low-flow state. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:245–7. doi: 10.1155/2007/920716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haviv YS, Reinus C, Zimmerman J. “Black esophagus”:A rare complication of shock. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2432–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigolon R, Fossà I, Rodella L, Targher G. Black esophagus syndrome associated with diabetic ketoacidosis. World J Clin Cases. 2016;4:56–9. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i2.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YH, Choi SY. Black esophagus with concomitant candidiasis developed after diabetic ketoacidosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5662–3. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i42.5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu MA, Mulki R, Massaad J. The black esophagus in the renal transplant patient. Case Rep Nephrol. 2019;2019:5085670. doi: 10.1155/2019/5085670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soussan BE, Savoye G, Hochain P, Herve S, Antonietti M, Lemoine F, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis:A 1-year prosective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:213–7. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grudell AB, Mueller PS, Viggiano TR. Black esophagus:Report of six cases and review of the literature 1963-2003. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:105–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available and will be provided by the corresponding author on a reasonable request.