Abstract

Objective

Caregiver burden is used frequently within the nursing literature. It has not yet been clearly defined as there are different opinions regarding this concept. The purpose of this paper is to provide clarity surrounding the concept caregiver burden.

Methods

An electronic search of MEDLINE, CINAHL, Health Source Nursing/Academic Edition and Academic Search Complete (ASC) of EBSCO, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Google Scholar were searched with a limit of 10 years and published in the English or Chinese language. The paper adopted the framework by Walker and Avant. The attributes, antecedents, consequences and uses of the concept were identified.

Results

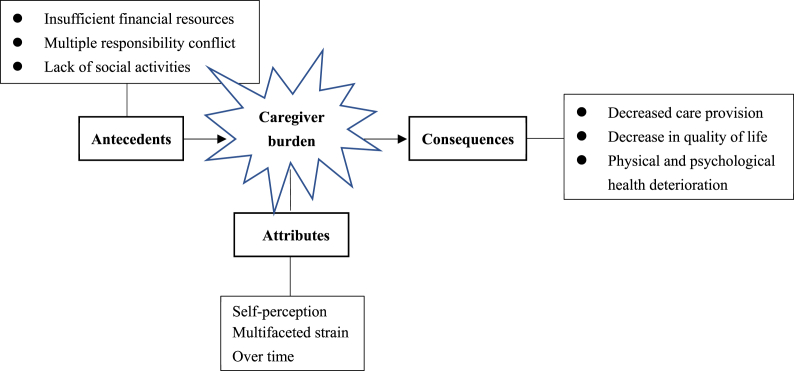

At total of 33 articles were included. The three attributes of caregiver burden were identified as self-perception, multifaceted strain, and over time. The antecedents included insufficient financial resources, multiple responsibility conflict, lack of social activities. The consequences of caregiver burden resulted in negative change which included decreased care provision, decrease in quality of life, physical and psychological health deterioration.

Conclusion

A definition of caregiver burden was developed. Tools to measure caregiver burden were identified. The findings from this analysis can be used in nursing practice, nursing education, research and administration.

Keywords: Burden, Caregivers, Cost of illness, Home nursing, Mental health, Quality of life

What’s known?

-

•

Globally, caregivers are instrumental in caring for family members and loved ones.

-

•

Caregivers experience burden when caring for family members and loved ones.

-

•

There are many different interpretations of caregiver burden in the literature.

What’s new?

-

•

Caregiver burden is the level of multifaceted strain perceived by the caregiver from caring for a family member and/or loved one over time.

-

•

The consequences of caregiver burden include negative consequences.

-

•

Healthcare organizations have significant roles in improving support structures for caregivers.

1. Introduction

With an aging population that continues to grow and the number of people living with chronic disease increasing, health care is shifting from hospital to community and family [1,2]. Family members are key to the delivery of long-term care for patients and loved ones [3,4]. An abundance of research notes that family caregivers experience a significant burden in providing care to patients with specific illness such as mental health illness [5], parkinson disease [6], dementia [7] and terminal cancer [8]. Although the concept of caregiver burden is not uncommon in the field of nursing research, a clear definition of “caregiver burden” is lacking [6,7]. Tamizi et al. [9] undertook a systematic review on the concept of caregiver burden in relation to schizophrenia and Mulud [10] conducted a concept analysis on caregiver burden in mental illness. Little is known about caregiver burden when caring for an individual with Alzheimer’s disease. The concept caregiver is often used interchangeably with terms such as “stress, problem and negative effects” [7] (p. 20), leading to a clear lack of understanding of the concept. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to clarify the concept of caregiver burden by reviewing the most recent and relevant literature and undertaking a concept analysis. The paper will be guided by the Walker and Avant’s framework [11].

2. Methods

2.1. Concept analysis method

This study was conducted using the Walker and Avant’s framework [11]. Walker and Avant state that the analysis of concept helps to reduce any ambiguity of the concept and thus clarify its definition, so as to avoid the inaccurate use of the concept in nursing theory and research [11]. This framework was used because of its step by step approach making it a user-friendly guide. According to McCarthy and Fitzpatrick [10] the framework by Walker and Avant is used most often in nursing. The eight steps include: 1) Selecting the concept; 2) Determining the aim of the analysis; 3) Identifying all the uses of the concept; 4) Identifying the defining attributes; 5) Constructing a model case; 6) Constructing cases such as borderline, related and contrary cases; 7) Identifying antecedents and consequences and 8) Determining empirical references [11].

2.2. Selecting the concept

The concept of caregiver burden is significant in nursing science and practice. Pearlin and Skaff [12] believe that caregiver burden is similar to being exposed to a severe, long term chronic stressor. The lack of awareness around caregiver burden can have huge implications for the healthcare system globally. Due to the ambiguities in the literature surrounding the concept of caregiver burden, this concept was selected for analysis.

2.3. Data sources

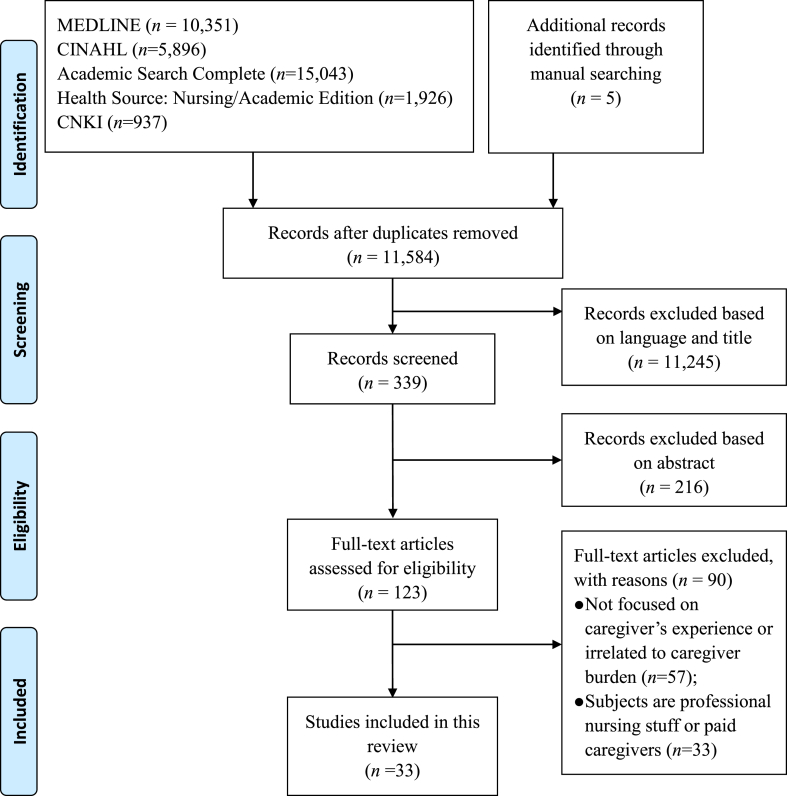

The following electronic databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, Health Source Nursing/Academic Edition and Academic Search Complete (ASC) of EBSCO, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Google Scholar were searched. The author combined keywords in different ways, including “caregiver burden”, “carer burden”, “carer or caregiver or family member or relatives or informal caregivers”, and “burden, stress, fatigue, strain or burnout”. The Boolean operator ‘AND’ was used to combine search results. The limitations imposed included literature published (a) in the English or Chinese language, (b) between 2010 and 2020, (c) peer-reviewed, and (d) full text. A manual search was also carried out by examining the reference lists to identify additional literature that could be included. Subsequently 33 studies in the area of health care sciences were included and analyzed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3. Results

3.1. Uses of the concept

Caregiver burden can be defined as the strain or load borne by a person who cares for a chronically ill, disabled, or elderly family member [13]. Caregiver burden is related to the well-being of both the individual and caregiver; therefore, understanding the attributes associated with caregiver burden is important.

Hoenig and Hamilton [14] first proposed the concept of burden and believed that burden could be divided into subjective and objective burden. Subjective burden primarily involves the personal feelings of carers generated while performing the caring function, while objective burden is defined as events or activities related to negative caring experiences [14]. Zarit, Reever, and Bach-Peterson [15] delineated burden as “the extent to which caregivers perceived their emotional, physical health, social life, and financial status as a result of caring for their relative” (p. 261). In addition, these authors considered burden to arise from a particular, non-objective, explanatory procedure [15]. Collins et al. [16] proposed that caregiver burden refers to psychological pain, physical health issues, financial and social strains, impaired family relationships, a sense of hopelessness and other negative outcomes of care tasks. In 1999, Nijboer et al. [17] argued that caregiver burden was a multidimensional concept that included both optimistic and pessimistic aspects of providing care. In the dictionary [18], burden is defined as “a duty, responsibility, etc., that causes worry, difficulty or hard work” (p. 196). To date, literature supports the notion that caregiver burden is a complicated concept due to its multidimensional construction [[19], [20], [21]].

3.2. Relevant concepts

Related concepts are usually terms that are used interchangeably with a concept and have similar meanings which can be distinguished by conceptual analysis [11]. There is a lack of clarity around the concept of caregiver burden and the alternate usage of terms such as stress, distress, tension, and burnout instead of burden [10,22]. Stress is the most common synonym used by researchers to represent caregiver burden in the literature.

Caregiver stress: Caregiver stress is considered both subjective and objective. Subjective stress refers to the emotional or cognitive responses of the caregiver, such as fatigue, inequality, or the perception of the current state of caregiving. Objective stress mainly reflects the care responsibility assumed by the caregiver, which is a measurement based on the need of care-recipients [23,24].

3.3. The defining attributes of caregiver burden

The key aspect of a concept analysis is to determine the defining attributes. Attributes are the features that appear repeatedly in the literature and are the critical attributes of the concept according to Walker and Avant [11]. The three key attributes of caregiver burden identified from the literature are self-perception, multifaceted strain, and over time.

3.3.1. Self-perception (perceived by an individual)

Self-perception is about the caregiver reflecting on personal experience during the caregiving process. Even though the literature alludes to subjective and objective perception, the author of this article believes that caregiver burden can be subsumed into self-perception. According to Bhattacharjee et al. [25], caregiver burden refers to “the positive or negative feelings and perceptions of the caregiver associated with providing caregiving functions” (p. 114). It is logical that among caregivers in the same nursing context, the level of perceived burden varies. A mixed approach study on caregiver burden conducted by De Korte-Verhoef et al. [26] reported that more than half of family carers experienced a high level of burden; however, only a quarter of the caregivers expressed that their burden negatively affected their daily life.

3.3.2. Multifaceted strain

The fact that caregiver burden is multidimensional has been extensively demonstrated in the literature. Due to the long-term care [27], the caregivers of patients with end-stage cancer pay limited attention to their own state of health [4] and often suffer from health problems, such as weight loss [28], fatigue [28,29] and sleep disturbances [30,31]. Emotional distress [32] and psychological stress [30] are also common among carers. In terms of family function, numerous studies [30,33,34] have illustrated that caregiver burden often causes alienation or deteriorates of family relationships. Furthermore, providing long-term care [35] can disrupt the caregiver’s schedule [27,28,31] and lifestyle [34], thereby limiting social activities [27,30] and, resulting in the feeling of being socially isolated [29,33,36]. Varying degrees of economic problems faced by caregivers have also been frequently reported [27,28,30,34,37,38].

3.3.3. Over time

Caregiver burden, in essence, is not always static [28,35,39,40]. Many published studies suggest that the longevity of caregiving, social/family support, and the trajectory of disease are all factors that significantly affect the level of burden on caregivers [28,35,39,40]. A longitudinal study conducted in Taiwan indicated that the overall burden levels perceived by caregivers changed dynamically over time and that having another family member in need of care or no one who could share the care task was significantly correlated with change in the caregiver burden [28]. On the other hand, a cross-sectional investigation from Malaysia was conducted among family caregivers of chemotherapy patients, and a scaled assessment illustrated that the burden on caregivers decreased over time. According to the stress adaptation theory, caregivers master various nursing skills step by step over time and gradually adapt to the pressure brought by caring tasks [35]. The results of a quantitative study of the informal caregivers’ burden of breast cancer patients showed that the external support can help caregivers adapt to changing roles, thereby reducing the burden [39].

3.4. Cases

According to Walker and Avant the description of cases includes the facilitation of and in-depth understanding of the concept under study. Generally, model cases, related cases, borderline cases, and contrary cases are the most common used cases [41].

3.4.1. Model case

A model case is a real-life example containing all the defining attributes in the clinical scenario [41]. A model case is the best example of using a concept because it illustrates all of the defining attributes of the concept [41].

Mei was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease following the death of her husband. Her two sons live in another city. Lily, her daughter, is her primary caregiver and takes care of her daily life, while her two sons can call only once a month to say hello. In addition to daily chores, such as laundry and cooking, Lily also manages the medication regime and accompanies her mother on hospital visits. Lily does not participate in activities with her friends as she is preoccupied with her mother. Lily is feeling stressed and burdened (self-perception) which is causing insomnia, irritability, and a loss of appetite (multifaceted strain). Lately, her mother’s condition is getting worse, and sometimes she does not even recognize Lily. More often than not, Mei forgets to turn off the gas or take her medicine. Therefore, Lily leaves her job and cares for her mother full time. Her mother is unsafe to be left alone. With insufficient family support and no institutions to provide day-to-day care in the community, Lily feels more burdened than before. Recently, she suffered from weight loss, depression, and other health related problems (over time).

This case includes all the attributes of caregiver burden which are highlighted in bold. Lily was well aware of the burden of caring for her mother. When Lily left her job to care for her mother full-time, it led to financial presure. Lily began to show signs of strain. Lily had no family or community support. Over a period of time, Lily’s health deteriorated even more.

3.4.2. Related case

Related cases refer to the examples that are related to a concept, but do not contain all of the attributes of the concept [41].

Mei was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease following the death of her husband. Lily, her daughter, is her primary caregiver and takes care of her daily life. In addition to daily chores, such as laundry and cooking, Lily also manages the medication regime and accompanies her mother on hospital visits. Lily does not participate in activities with her friends as she is preoccupied with her mother. However, this is causing insomnia, irritability, and a loss of appetite (multifaceted strain). Lily loves her mother very much and seems to readily accept that the stresses are part of caregiving. Besides, Lily’s brother often visits or calls to make sure that Lily is coping. With her brother’s care and support, Lily accepts this way of life.

In this case, Lily is feeling the strain but is aware of it. Despite caring for her mother causing insomnia and irritability, Lily accepts that this is part of her life style and a way of showing love. This strain is likened to the concept of stress. Lily accepts her brothers’ support, and he visits regularly. There are many resources that Lily has implemented to make caring for her mother easier. Lily is able to cope with this and does acknowledge that it is stressful.

3.4.3. Borderline case

According to Walker and Avant [41], the borderline case includes the majority of the defining attributes of the concept.

Mei was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease following the death of her husband. Lily, her daughter, is her primary caregiver and takes care of her daily life. In addition to daily chores, such as laundry and cooking, Lily also manages the medication regime and accompanies her mother on hospital visits. Lily does not participate in activities with her friends as she is preoccupied with her mother. Lily is feeling stressed and burdened (self-perception) which is causing insomnia. One day, Lily told her brother about the caregiving experience. Then Lily’s brother started to visit and spend time with his mother so that Lily could take a break. With the care and support of her brother, Lily readily accepts this way of life and does not feel the burden (over time).

In this example, only two of the attributes are demonstrated, self-perception and over time. Lily felt the burden because of the major change in her life, which meant she had to be the primary caregiver for her mother. However, she shared her feelings with her brother and got help. Consequently, Lily no longer felt the strain of looking after her mother.

3.4.4. Contrary case

Contrary case, as opposed to the model case, does not contain any of the defining attributes of the concept [41].

Mei was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease following the death of her husband. Lily, her daughter, is her primary caregiver and takes care of her daily life. In addition to daily chores, such as laundry and cooking, Lily also manages the medication regime and accompanies her mother on hospital visits. Lily loves her mother very much and seems to readily accept caring for her. However, she does not do it alone. Her brother visits daily so that Lily can go for a walk with her dog. Every Friday Lily arranges for her mother to visit a day centre so that Lily can spend time with her friends on a Friday.

This is a very good example of a full-time carer who will not experience caregiver burden. Lily did not display any of the defining attributes of caregiver burden.

3.5. Antecedents of caregiver burden

Antecedents are events that take place before the occurrence of the concept [41]. The reviewed studies show that the antecedents of caregiver burden are insufficient financial resources, multiple responsibility conflict and lack of social activities.

3.5.1. Insufficient financial resources

The cost of care is one of the key indicators of caregiver burden [42]. Carers often leave full time employment in order to care for loved ones which in turn can have an effect on the financial resources of carers. It has been reported that eighteen percent of caregivers report financial stress due to the provision of care [43].

3.5.2. Multiple responsibility conflict

The majority of caregivers are spouses, children, or relatives who perform multiple roles. They often struggle to balance these roles and fulfil caring responsibilities. Caregiving not only involves physical, psychological and spiritual support but also assumes many other forms [44]. Caregiving covers a wide range of responsibilities, such as, direct care, assistance in daily activities, emotional encouragement and medication monitoring [3]. More specifically, medication intake, follow-up visits, taking a bath, using the toilet, changing clothing, transportation, shopping are all included in care delivery tasks [44,45].

3.5.3. Lack of social activities

Caregiver burden is usually experienced by those who provide long-term care to others [37]. Goldstein et al. [46] described caregivers with restricted social networks are more prone to feeling burdened, which is consistent with the finding reported in previous studies [15,47].

3.6. Consequences of caregiver burden

Consequences are the factors derived from the literature that result from the concept [41]. The consequences of caregiver burden include negative consequences; decreased care provision, decrease in quality of life, physical and psychological health deterioration. The consequences of caregiver burden include consequences related to the caregiver and care recipient.

3.6.1. Decreased care provision

One of the consequences of caregiver burden is reduction in care provision. Caregivers experiencing caregiver burden without adequate support or resources, leads to a reduction in the quality of care provided [19]. A study by Given et al. [48] claims that the quality of care is reduced when a care giver is experiencing burden. It may be manifested due to a decreased coping ability, and lack of emotional support for the care-recipient. Furthermore, a child’s state of health (including physical and mental) is influenced by the physical and mental state of the parent (caregiver) and his/her perception of the child’s condition [21].

3.6.2. Decrease in quality of life

Several studies investigating the quality of life of caregivers show that caregivers’ quality of life is significantly related to caregiver burden [[49], [50], [51]] and that reducing caregivers’ burden can improve their quality of life [52]. As caregivers spend periods of time caring for patients every day, their daily activities are limited, and they have limited time to attend their own needs [27]. Overall, carers experience caregiver burden and have a reduced quality of life [53,54]. According to research of Weitzner et al. [55], the effect of caregiver burden on quality of life differs according to the phase of illness the recipient is experiencing at any given time.

3.6.3. Physical and psychological health deterioration

Caregivers devote a large amount of time and energy to caring for their loved ones while seldom caring about themselves. Because of the lack of rest time, caregivers often neglect to take care of themselves, even when sick, and rarely seek medical help [59]. More than 50% of family carers report chronic health issues such as heart problems and hypertension [56,57]. Additionally, caregivers experienced varying degrees of physical fatigue and decreased health after long-term care are also well documented in the literature [56,57]. On the other hand, researchers at home and abroad [49,58] have described that caregivers experience’ psychological problems and primarily feel depressed, angry, worried, guilty, and anxious. Family caregivers helping during the late stage of cancer had significantly more anxiety/depression than the general population and were more susceptible to mental impairment [59].

3.7. Empirical referents

Identifying empirical referents is an essential step in conceptual analyses used to show how concepts are measured or quantified in reality. In the review of the literature, 24 out of the 33 studies utilized a variety of tools to measure caregiver burden (Table 1). The most commonly used measurement tools in the literature are The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) [20,36,38,39,[60], [61], [62], [63]] and The Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale (CRA) [2,28,29,35,37,[64], [65], [66]].

Table 1.

The tools used to measure caregiver burden.

| Tool | Number of items | Rating scale | Aspects | Reliability (Cronbach’s α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) [36] | 22 | 5-point Likert scale (0–4) | Personal stress Role stress |

0.85–0.89 |

| Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale (CRA) [28] | 24 | 5-point Likert scale (1–5) | Self-esteem Inadequate family support Effect on economics Effect on schedule Effect on health |

0.70–0.76 |

| Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) [67] | 24 | 5-point Likert scale (0–4) | Time dependence Develop of mental issues Physical effects Social life impact Emotional drain |

0.90 |

| Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) [45] | 13 | yes (=1), no (=0) | Occupation Effect on economics Physical effects Social life impact Time domain |

0.69 |

| Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale (ZBS) [51] | 22 | 5-point Likert scale (0–4) | Negative emotions Physical effects Social life impact Economic impact |

0.91 |

In 1980, Zarit, Reever, and Bach-Peterson developed the first ever scale to assess the effect of care on caregivers known as the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (ZBI). This scale has been modified and revised over the years [15]. Currently, the Lite versions of the tool, such as the ZBI-22 [36], ZBI-12 [63], ZBI-7 [20], are widely used to measure caregiver burden. The Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale (CRA) [68] measures the multidimensional aspects of caregivers’ suffering. It is a self-reported questionnaire containing 24 items. The 24 items are subsumed into five subscales [65].

Although both scales can measure the subjective and objective burden of caregiver, the CRA cannot measure caregiver burden in the spiritual realm [69]. The ZBI has been translated into various languages such as Japanese [36] and Korean [62] and has received attention due to the addition of the spirituality aspect within the scale. However, due to the increasing complexity of the concept, it is recommended that new tools are developed to measure the concept of caregiver burden from the caregiver perspective and the care recipient perspective.

3.8. Definition of the concept

Based on the analysis, caregiver burden can be defined as “the level of multifaceted strain perceived by the caregiver from caring for a family member and/or loved one over time”. Fig. 2 show presents the conceptual model of caregiver burden developed based on the findings of this analysis.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model of caregiver burden.

4. Discussion

The literature concluded that caregiver burden is a series of negative responses that occur while undertaking the role of primary caregiver. The negative responses include both subjective and objective outcomes. Thus, caregiver burden is a complex, multi-dimensional concept [21]. While the present study indicated that one of the attributes of caregiver burden is self-perception it differs from earlier conceptual analyses papers on caregiver burden. Chou [21] found that caregiver burden is an individual’s subjective evaluation of the present caregiving situation and measurement of the degree of difficulties. However, caregiver burden includes both subjective and objective aspects. Perception is seen as objective or subjective since it is the ability of an individual to observe or listen to things through their senses, or the way in which they regard, understand and interpret them [70].

The present study showed that the antecedents of caregiver burden are insufficient financial resources, multiple responsibility conflict and lack of social activities. Financial and economic restraint is an important factor associated with caregiver burden [43]. Caregivers with financial and economic pressure may experience more burden despite the government providing financial assistance to patients with chronic illness to help the caregivers reduce the burden [39]. Caregivers often provide long-term care for loved ones in their roles as spouses, partners and children. Conflict between career, caregiving responsibilities, and family needs place higher levels of burden on the caregiver. Therefore, caregiver burden needs to be understood so that healthcare professionals can provide the necessary supports. Studies demonstrated that caregivers who perceive their social support to be high experienced decreased levels of caregiver burden [39]. Family, community and social support are important aspects of caregivers. Organizations that offer emotional support and counseling, and community day care centers can help ease the caregiver’s burden by allowing the caregiver to take adequate rest [71].

5. Limitations of the study

Caregiver burden may vary across caregivers caring for patients with different diseases or at different stages [61]. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies focus on specific types of disease or illness to obtain a more accurate understanding of the concept of caregiver burden as it relates to disease and the status of patients’ conditions.

6. Conclusion

Clarifying the concept of caregiver burden is essential for helping healthcare professionals and the general population to obtain a better understanding of caregiver burden. This paper clearly clarifies the meaning of caregiver burden. It is necessary for healthcare professionals and caregivers to clearly understand the meaning of caregiver burden from the perspective of the caregiver. Nurses can now assess caregiver burden by using measurement tools and thus develop interventions and support mechanisms to support caregivers. This concept analysis provides information which can be used in nursing practice, education, research and management.

7. Future implications in nursing research

Having a deep understanding of the concept of caregiver burden is key to understanding caring from the perspective of the caregiver. Healthcare organizations need to implement support structures to alleviate caregiver burden on caregivers. Caregivers play a vital role in reducing costs and resources on the healthcare system by caring for loved ones at home. Therefore, it is essential to take care of caregivers to reduce the long-term effects of caregiver burden.

Further studies are recommended to determine caregiver burden from the perspective of the care recipient. Additionally, developing new strategies for specific diseases and expanding the research scope of caregiver burden are also critical.

Funding

This work is supported by the 2019 Health Research Project of Sichuan Province (No.19PJ045). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhu Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft. Catrina Heffernan: Writing - review & editing. Jie Tan: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the support of the librarians at the Institute of Technology Tralee, Co. Kerry, Ireland.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Nursing Association.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Roberts A.A. The labor market consequences of family illness. J Ment Health Pol Econ. 1999;2:183–195. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-176x. 199912)2:4<183::aid-mhp62>3.3.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharpe L., Butow P., Smith C., McConnell D., Clarke S. The relationship between available support, unmet needs and caregiver burden in patients with advanced cancer and their carers. Psycho Oncol. 2005;14:102–114. doi: 10.1002/pon.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamataki Z., Ellis J.E., Costello J., Fielding J., Burns M., Molassiotis A. Chronicles of informal caregiving in cancer: using “The Cancer Family Caregiving Experience” model as an explanatory framework. Support Care Canc. 2014;22:435–444. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1994-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui J., Song L.J., Zhou L.J., Meng H., Zhao J.J. Needs of family caregivers of advanced cancer patients: a survey in Shanghai of China. Eur J Canc Care. 2014;23:562–569. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gharavi Y., Stringer B., Hoogendoorn A., Boogaarts J., Van Raaij B., Van Meijel B. Evaluation of an interaction-skills training for reducing the burden of family caregivers of patients with severe mental illness: a pre-posttest design. BMC Psychiatr. 2018;18:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1669-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee G.B., Woo H., Lee S.Y., Cheon S.M., Kim J.W. The burden of care and the understanding of disease in Parkinson’s disease. PloS One. 2019;14:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinquart M., Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumont S., Turgeon J., Allard P., Gagnon P., Charbonneau C., Vézina L. Caring for a loved one with advanced cancer: determinants of psychological distress in family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:912–921. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamizi Z., Fallahi-khoshknab M., Dalvandi A., Mohammadi-shahboulaghi F. vols. 6–11. 2019. (Defining the concept of family caregiver burden in patients with schizophrenia : a systematic review protocol). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy G., Fitzpatrick J. Springer Publishing Company; 2016. Nursing concept Analysis : applications to research and practice. New York. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker L.O., Avant K.C. fourth ed. Pearson Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River: New Jersey: 2005. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearlin L.I., Skaff M.M. Stressors and adaptation in late life. In: Gatz M., editor. Emerg. issues Ment. Heal. aging. American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 97–123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stucki B.R., Mulvey J. American Council of Life Insurers; 2000. Can aging baby boomers avoid the nursing home: long-term care insurance for" aging in place. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoenig J., Hamilton M.W. The schizophrenic patient in the community and his effect on the household. Int J Soc Psychiatr. 1966;12:165–176. doi: 10.1177/002076406601200301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarit S., Reever K., Bahc-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontol. 1980;20:649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins C.E., Given B.A., Given C.W. Interventions with family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Nurs Clin. 1994;29:195–207. PMID: 8121821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nijboer C., Triemstra M., Tempelaar R., Sanderman R., van den Bos G. Measuring both negative and positive reactions to giving care to cancer patients: psychometric qualities of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1259–1269. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hornby A., Turnbull J., Lea D., Parkinson D., Phillips P., Francis B., Webb S., Ashby M. eighth ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. Oxford advanced learner’s dictionary. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bastawrous M. Caregiver burden-A critical discussion. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa-Requena G., Espinosa Val M., Cristòfol R. Caregiver burden in end-of-life care: advanced cancer and final stage of dementia. Palliat Support Care. 2013;13:583–589. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513001259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou K.R. Caregiver burden: a concept analysis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2000;15:398–407. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2000.16709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grandón P., Jenaro C., Lemos S. Primary caregivers of schizophrenia outpatients: burden and predictor variables. Psychiatr Res. 2008;158:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sisk R.J. Caregiver burden and health promotion. Int J Nurs Stud. 2000;37:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(99)00053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llanque S., Savage L., Rosenburg N., Ba H., Caserta M. Concept Analysis : Alzheimer ’ s caregiver stress. Nurs Forum. 2014;51:21–31. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattacharjee M., Vairale J., Gawali K., Dalal P.M. Factors affecting burden on caregivers of stroke survivors: population-based study in Mumbai (India) Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:113–119. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.94994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Korte-Verhoef M.C., Pasman H.R.W., Schweitzer B.P., Francke A.L., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B.D., Deliens L. Burden for family carers at the end of life; A mixed-method study of the perspectives of family carers and GPs. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon S.J., Kim J.S., Jung J.G., Kim S.S., Kim S. Modifiable factors associated with caregiver burden among family caregivers of terminally ill Korean cancer patients. Support Care Canc. 2014;22:1243–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee Y.H., Liao Y.C., Shun S.C., Lin K.C., Liao W.Y., Chang P.H. Trajectories of caregiver burden and related factors in family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. Psycho Oncol. 2018;27:1493–1500. doi: 10.1002/pon.4678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ateş G., Ebenau A.F., Busa C., Csikos Á., Hasselaar J., Jaspers B. “never at ease” - family carers within integrated palliative care: a multinational, mixed method study. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arian M., Younesi S.J., Khanjani M.S. Explaining the experiences and consequences of care among family caregivers of patients with cancer in the terminal phase: a qualitative research. Int J Cancer Manag. 2017;10 doi: 10.5812/ijcm.10753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jean Shih W.M., Hsiao P.J., Chen M.L., Lin M.H. Experiences of family of patient with newly diagnosed advanced terminal stage hepatocellular cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2013;14:4655–4660. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.8.4655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi Y.S., Hwang S.W., Hwang I.C., Lee Y.J., Kim young S., Kim H.M. Factors associated with care burden among family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;19:61–69. doi: 10.14475/kjhpc.2016.19.1.61. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adejumo O.A., Iyawe I.O., Akinbodewa A.A., Abolarin O.S., Alli E.O. Burden, psychological well-being and quality of life of caregivers of end stage renal disease patients. Ghana Med J. 2019;53 doi: 10.4314/gmj.v53i3.2. 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen L., Rosenkranz S.J., Wherity K., Sasaki A. Living with hepatocellular carcinoma near the end of life: family caregivers’ perspectives. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44:562–570. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.562-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramli S.F., Pardi K.W. Factors associated with caregiver burden of family with a cancer patient undergoing chemotherapy at a Tertiary Hospital, Malaysia. Int Med J. 2018;25:99–102. http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=921d30ed-028d-44cd-9a30-d64788beb602%40sessionmgr4007 Retrieved from EBSCOhost. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagata C., Yada H., Inagaki J. Exploration of the factor structure of the burden experienced by individuals providing end-of-life care at home. Nurs Res Pract. 2018;1–9 doi: 10.1155/2018/1659040. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park C.H., Shin D.W., Choi J.Y., Kang J., Baek Y.J., Mo H.N. Determinants of the burden and positivity of family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients in Korea. Psycho Oncol. 2012;21:282–290. doi: 10.1002/pon.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen D.L., Chao D., Ma G., Morgan T. Quality of life and factors predictive of burden among primary caregivers of chronic liver disease patients. Hell Soc Gastroenterol. 2015;28:124–129. PMID: 25608915. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabriel I.O. Caregiver burden among informal caregivers of women with breast cancer. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2019;15:1–9. doi: 10.26717/bjstr.2019.15.002704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu X., Dolansky M.A., Hu X., Zhang F., Qu M. Factors associated with the caregiver burden among family caregivers of patients with heart failure in southwest China. Nurs Health Sci. 2016;18:105–112. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker L.O., Avant K.C. fifth ed. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs , N.J.: 2011. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fink S. The influence of family resources and family demands on the strains and well-being of caregiving families. Nurs Res. 1995;44:139–146. PMID: 7761289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Alliance for Caregiving . 2020. Caregiving in the U.S. Washingt DC.https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united-states-2015-report-revised.pdf Greenwald Assoc 2015. Retrieved from Aarp. org. February 10. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toseland R.W., Smith G.M.P. Handbook of social work practice with vulnerable and resilient populations. In: Gitterman A., editor. Fam. caregivers frail Elder. Columbia University Pres; 2001. US. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bekdemir A., Ilhan N. Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of bedridden patients. J Nurs Res. 2019;27 doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldstein N.E., Wood R., Clinical J., Program S. Factors associated with caregiver burden among caregivers of tenninally TIl patients with cancer. J Palliat Care. 2004;20:38–43. doi: 10.1177/082585970402000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pruchno R.A., Resch N.L. Husbands and wives as caregivers: antecedents of depression and burden. Gerontol. 1989;29:159–165. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Given B.A., Sherwood P., Given C.W. Support for caregivers of cancer patients: transition after active treatment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20 doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0611. 2015–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang X.S. China Medical University; 2010. The relationship of cancer caregiver burden, Quality of life and depression (master’s thesis) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Q.P., Yuen Loke A. The research status of family caregivers for patients with. Chin J Nurs. 2012;47:1132–1135. doi: 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2012.12.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ribé J.M., Salamero M., Pérez-Testor C., Mercadal J., Aguilera C., Cleris M. Quality of life in family caregivers of schizophrenia patients in Spain: caregiver characteristics, caregiving burden, family functioning, and social and professional support. Int J Psychiatr Clin Pract. 2018;22:25–33. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2017.1360500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larson J., Franzén-Dahlin Å., Billing E., Von Arbin M., Murray V., Wredling R. Predictors of quality of life among spouses of stroke patients during the first year after the stroke event. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19:439–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grant M., Sun V., Fujinami R., Sidhu R., Otis-Green S., Juarez G. Family caregiver burden, skills preparedness, and quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:337–346. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.337-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray S.A., Kendall M., Boyd K., Grant L., Highet G., Sheikh A. Archetypal trajectories of social, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing and distress in family care givers of patients with lung cancer: secondary analysis of serial qualitative interviews. BMJ. 2010;340:1401. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weitzner M.A., McMillan S.C., Jacobsen P.B. Family caregiver quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1999;17:418–428. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thornton A.A., Perez M.A., Meyerowitz B.E. Patient and partner quality of life and psychosocial adjustment following radical prostatectomy. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2004;11:15–30. doi: 10.1023/B:JOCS.0000016266.06253.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mellon S., Northouse L.L. Family survivorship and quality of life following a cancer diagnosis. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24:446–459. doi: 10.1002/nur.10004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coppel D.B., Burton C., Becker J., Fiore J. Relationships of cognitions associated with coping reactions to depression in spousal caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Cognit Ther Res. 1985;9:253–266. doi: 10.1007/BF01183845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song J.I., Shin D.W., Choi J.Y., Kang J., Baik Y.J., Mo H. Quality of life and mental health in family caregivers of patients with terminal cancer. Support Care Canc. 2011;19:1519–1526. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0977-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Demir Barutcu C. Relationship between caregiver health literacy and caregiver burden. Puert Rico Health Sci J. 2019;38:163–169. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=5d8de0d5-4a4d-4e83-9f4c-104e9bea1ae7%40pdc-v-sessmgr04 Retrieved from EBSCOhost. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramzani A., Zarghami M., Charati J.Y., Bagheri M., Lolaty H.A. Relationship between self-efficacy and perceived burden among schizophrenic patients’ caregivers. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2019;4:91–97. doi: 10.4103/JNMS.JNMS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seo Y.J., Park H. Factors influencing caregiver burden in families of hospitalised patients with lung cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28 doi: 10.1111/jocn.14812. 1979–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schrank B., Ebert-Vogel A., Amering M., Masel E.K., Neubauer M., Watzke H. Gender differences in caregiver burden and its determinants in family members of terminally ill cancer patients. Psycho Oncol. 2016;808–14 doi: 10.1002/pon.4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wadhwa D., Burman D., Swami N., Zimmermann C. Quality of life and mental health in caregivers of outpatients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29 doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.9110. 9110–9110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoon S.J., Kim J.S., Jung J.G., Kim S.S., Kim S. Modifiable factors associated with caregiver burden among family caregivers of terminally ill Korean cancer patients. Support Care Canc. 2014;22:1243–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hartnett J., Thom B., Kline N. Caregiver burden in end-stage ovarian cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:169–174. doi: 10.1188/16.CJON.169-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Senturk S.G., Akyol M.A., Kucukguclu O. The relationship between caregiver burden and psychological resilience in caregivers of individuals with dementia. Int J Caring Sci. 2018;11:1223–1230. doi: 10.29399/npa.22964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Given C.W., Given B., Stommel M., Collins C., King S., Franklin S. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15:271–283. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choi S., Seo J.Y. Analysis of caregiver burden in palliative care: an integrated review. Nurs Forum. 2019;54:280–290. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.LEXICO s.v. perception. https://www.lexico.com/definition/perception

- 71.Swartz K., Collins L.G. Caregiver care. Am Fam Physician. 2011;99:699–706. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/0601/p1309.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.