Abstract

Healthcare provider barriers to cessation resources may be undercutting quit rates for smokers with serious mental illness (SMI). The study aim was to examine how providers influence cessation treatment utilization among smokers with SMI. Data were taken from a trial conducted among smokers in Minnesota Health Care Programs. The sample was split into groups of participants with SMI (n=939) and without SMI (n=1382). Analyses assessed whether the association between SMI and treatment utilization was mediated by healthcare provider-delivered treatment advice and healthcare provider bias. Results revealed higher rates of treatment utilization among smokers with SMI than those without SMI (45.9% vs 31.7%, p<0.001); treatment advice and provider bias did not mediate this association. Subsequent individual regression analyses revealed positive associations between treatment advice and treatment utilization (β: 0.21 – 0.25, p<0.05), independent of SMI status. Strategies to increase low-income smokers’ contacts with providers may reduce treatment utilization barriers among these smokers.

Keywords: smoking cessation, smoking cessation treatment, mental disorders, socioeconomic status, health insurance, access to health care, healthcare providers

Introduction

Socioeconomic disadvantage is strongly associated with heightened rates of cigarette smoking. While the prevalence of smoking is about 15% in the general population, more than 25% of those who live below the poverty level are current smokers.1 Those experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage also tend to have higher rates of mental illness, as the prevalence of mental health disorders is higher among low-income populations,2 those with lower educational attainment,2 and the unemployed.3 Given that low socioeconomic standing and mental illness contribute independently to smoking risk,4 this population is at substantially elevated risk for smoking-related morbidity and mortality.

Increased attention to the mental health disparity in smoking prevalence has contributed to research demonstrating the effectiveness of multiple smoking cessation treatment modalities for this population. Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) has been shown to be effective among those with mental health disorders,5–7 as have Varenicline and Bupropion.8,9 With respect to non-pharmacological treatments, studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for smokers with depression10,11 and motivational interviewing for smokers engaged in mental health services.7

Although a large body of evidence suggests that pharmacological and counseling-based treatments are effective and well-tolerated by smokers with mental health disorders, efforts to reduce the mental health disparitiy in smoking rates requires a thorough examination of the barriers and facilitators to their use. One important factor may be these smokers’ interactions with their healthcare providers. The Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) recommends that healthcare providers “ask”, “advise”, “assess”, “assist”, and “arrange” (5As) assistance for all patients who identify as smokers, and the 2008 USDHHS clinical guidelines recommend that smokers with mental health disorders should be offered the same cessation treatment options as the general population.12 However, existing evidence suggests that this population may experience heightened healthcare provider barriers that could be undercutting their rates of treatment use. First, healthcare providers face competing treatment demands for smokers with mental health disorders,13,14 lending to the perception that smoking cessation is not a treatment priority and possibly contributing to lower levels of cessation care. Some providers also express beliefs that their patients are not interested in quitting smoking and are skeptical about the value of delievering the 5As in the context of mental health visits. In addition, research suggests that some healthcare providers are uncomfortable interacting with patients with mental health disorders15 and that healthcare provider endorsement of mental health stigma is associated with a reduced willingness to refill prescriptions.16 Because publicly subsidized insurance programs like Medicaid often require a prescription in order to receive free or reduced cost medications, access to cessation treatment may be further reduced for smokers enrolled in these programs.

Despite evidence demonstrating that smoking cessation treatments are effective for smokers with SMI, little is known about their rates of cessation treatment utilization. As such, the first aim of this study was to compare rates of cessation treatment utilization among smokers with SMI and without SMI in a low-income sample of Minnesota Health Care Programs (MHCP) enrollees. Given the heightened treatment access and utilization barriers suggested by the existing literature, it was hypothesized that smokers with SMI would use treatments at lower rates than those without SMI. The primary aim was to test the hypothesis that lower rates of healthcare provider-delivered advice to use cessation treatments and heightened perceptions of healthcare provider bias would mediate the relationship between SMI and lower rates of cessation treatment utilization.

Methods

Study Design

Data were obtained from the randomized controlled trial, “Offering Proactive Tobacco Treatment INtervention” (OPTIN) (N=2406), a study that demonstrated the effectiveness of a proactive outreach smoking cessation intervention among socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers enrolled in MHCP.17,18 The study population sample was stratified by age group (18–24, 25–34, 35–64), gender (male or female), and MHCP insurance program (Medicaid or MinnesotaCare).

Participants

Investigators collected MHCP insurance claims data from a 2-year period before the study, and ICD-9 codes indicating diagnoses of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, psychotic disorder, bipolar disorders, and/or severe or recurrent major depressive disorder were extracted from these data. Participants with ICD-9 codes indicating the presence of at least one of these diagnoses were categorized as having SMI (n=939); those without any of these diagnoses were categorized as not having SMI (n=1382). Participants for whom there were no insurance claims data for this 2-year period (n=85) were excluded from these analyses. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Minnesota and the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS).

Measures

Measures were obtained from OPTIN baseline and follow-up surveys and from MHCP administrative and insurance claims data.

Baseline Characteristics

Age, gender, insurance program, employment status, income, and race/ethnicity were assessed.

Mental Health Diagnoses

Participants with an ICD-9 code from 1) 295.00 to 295.94 were categorized as having a schizophrenic disorder, 2) 297.00 to 298.9 were categorized as having a psychotic disorder, 3) 296.2 to 296.36 were categorized as having a severe/recurrent major depressive disorder, 4) 296.00 to 296.13 and/or 296.4 to 296.9 were categorized as having a bipolar disorder.

Smoking History

Questions from the California Tobacco Survey19 and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System20 were used to assess the number of cigarettes smoked per day (CPD) and time until first cigarette after waking.

Social Environment

Items assessed the proportion of participants’ friends and family who were current smokers and rules for smoking within their home. Participants’ also reported perceived social support for cessation on a one to five scale, with higher scores indicating greater levels of support.19

Healthcare Provider

Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures assessed participants’ healthcare experiences.21 An item assessed whether participants had someone they considered to be their regular healthcare provider.

Mediators at Baseline

Healthcare Provider-Delivered Cessation Advice

Additional HEDIS measures assessed whether the participants had received healthcare provider-delivered advice to use cessation medication and advice to use treatments other than products to help with quitting in the past year.21

Healthcare Provider Bias

A composite variable of perceptions of healthcare provider bias was created by taking the sum of three items from the Physician Bias and Interpersonal Cultural Competence Measures Scale.22 These items assessed whether the participant felt they were treated with respect, the healthcare provider’s understanding of the participant’s background and values, and the participant’s perception of whether the healthcare provider looked down on their way of life. Each of these items was assessed on a one to five scale, with higher values indicating more perceived bias. The summary measure for these items yielded a Cronbach’s alpha reliability score of 0.74.

Outcomes at 12-Month Follow-Up

Cessation Treatment Utilization

At twelve-months, survey items assessed whether participants used NRT products, prescription cessation medications, or behavioral counseling in the past year. These items were used to create dichotomized outcome measures indicating the use of any medication, any counseling, and any form of treatment use.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline Characteristics

Participants in the SMI and non-SMI groups were compared across a series of baseline measures using t-tests and Pearson’s chi-square tests (Table 1).

Cessation Treatment Utilization

Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to compare rates of the treatment utilization in the SMI and non-SMI groups at 12-month follow-up (Table 2).

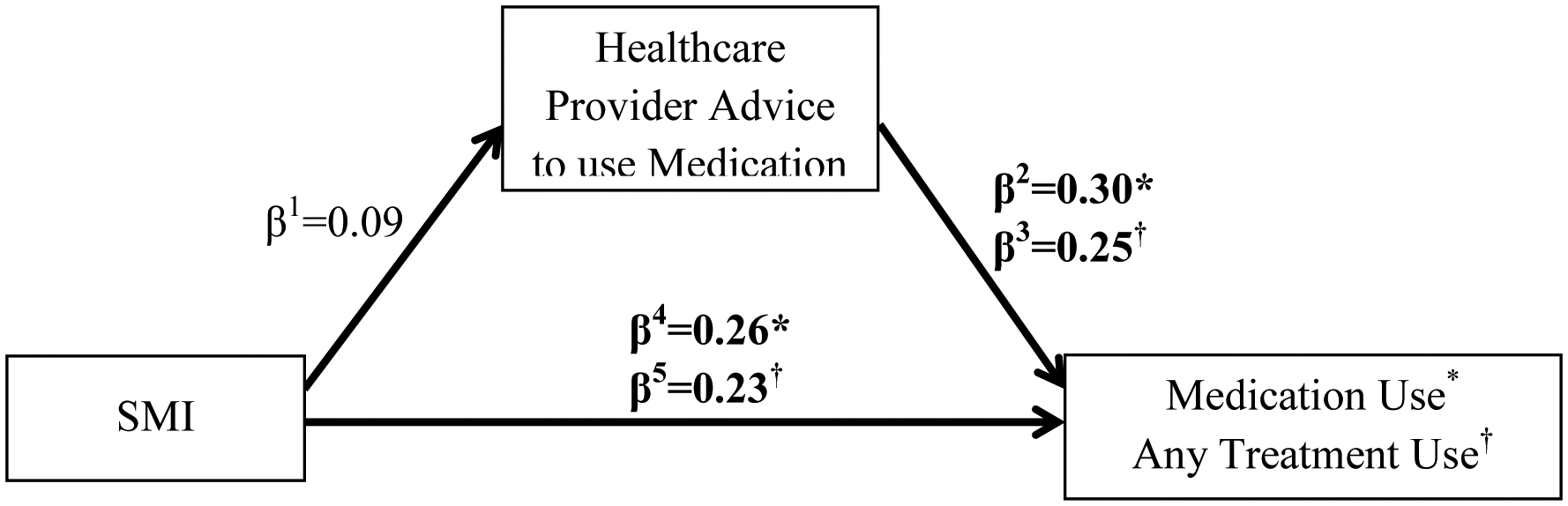

Individual Regression Analyses

Poisson regressions were used to assess associations between SMI and baseline measures of 1) healthcare provider-delivered advice to use medication (NRT and/or prescription) and 2) healthcare provider-delivered advice to use cessation treatments other than products, while linear regression was used to assess 3) participants’ perceptions of healthcare provider bias. Subsequent Poisson regressions assessed associations between baseline healthcare provider measures and the treatment utilization outcomes. The healthcare provider-delivered advice to use medication variable was paired with 1) utilization of medication (NRT and/or prescription), and 2) utilization of any cessation treatment (Figure 1). The healthcare provider-delivered advice to use treatments other than products variable was paired with 1) utilization of counseling, and 2) utilization of any cessation treatment (Figure 2). The perceptions of healthcare provider bias variable was paired with utilization of any cessation treatment (Figure 3).

Mediation Analyses

Mediation analyses were conducted using a macro developed for SAS version 9.2.23 These analyses adhered to a counterfactual approach, which asserts that the total effect of the main exposure (SMI) on the outcome variable (cessation treatment utilization) can be decomposed into direct effects and indirect effects, or meditational effects.24 The direct effect is the amount of change that would occur in cessation treatment utilization in the presence versus the absence of SMI, if for each individual the mediator (healthcare provider-delivered treatment advice or healthcare provider bias, respectively) was kept at the level it would hold if each individual did not have SMI. The indirect effect expresses how much the outcome would change on average if SMI was present, but the mediator was changed from the level it would take in the presence versus the absence of SMI.

One thousand bootstrap samples were produced for each set of mediation analyses, from which point estimates and confidence intervals were derived. Poisson regressions modeled the dichotomous treatment utilization outcomes, logistic regressions modeled the dichotomous treatment advice mediators, and linear regressions modeled the perceptions of healthcare provider bias mediator. Each exposure/mediator pairing was evaluated for statistical interaction in their effects on a given outcome. None of the pairings produced statistically significant interactions; thus, interaction terms were not included in the final analyses.

Model Building

In order to control for potential cofounding, both the individual regression analyses and the mediation analyses hierarchically adjusted for blocks of covariates. Initial analyses controlled only for the intervention condition (1). Subsequent models adjusted for sets of (2) demographic (insurance program, age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment, income), (3) smoking history (CPD, time until first cigarette after waking), (4) healthcare provider (whether participants had someone they considered to be their regular healthcare provider), and (5) social environment (proportion of close friends/family that are current smokers, social support for quitting, and home smoking rules) variables. Descriptions of the results focus on the most fully adjusted analyses (model 5).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Smokers with SMI were more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid, were older, and were more likely to be female than smokers without SMI. Smokers with SMI also tended to have lower educational attainment, were much less likely to be employed, and had lower annual income than those without SMI (Table 1). Participants with SMI smoked more cigarettes per day and were more likely to report smoking within 5 minutes of waking. Smokers with SMI had greater proportions of family/friends that were smokers and had similar levels of social support for quitting, and were more likely to report being able to smoke anywhere inside their home compared to those without SMI. Smokers with SMI were more likely to report having someone they considered to be their regular healthcare provider.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of SMI vs Non-SMI Smokers

| Characteristic | SMI N=939 | Non-SMI N=1382 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) or Mean±SD | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age | <.001 | ||

| 18–24 | 143 (15.2) | 308 (22.3) | . |

| 25–34 | 307 (32.7) | 496 (35.9) | . |

| 35–64 | 489 (52.1) | 578 (41.8) | . |

| Male | 250 (26.6) | 436 (31.6) | .011 |

| Insurance Program | |||

| Medicaid | 779 (83.0) | 895 (64.8) | <.001 |

| MnCare | 160 (17.0) | 487 (35.2) | . |

| Race/Ethnicity | .22 | ||

| White | 720 (76.7) | 1093 (79.1) | . |

| Black or African American | 116 (12.4) | 136 (9.8) | . |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 71 (7.6) | 92 (6.7) | . |

| Hispanic or Latino | 14 (1.5) | 28 (2.0) | . |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 18 (1.9) | 33 (2.4) | . |

| Education | .005 | ||

| Grade 11/lower | 145 (15.8) | 173 (12.8) | . |

| HS grad/GED | 305 (33.3) | 457 (33.8) | . |

| Some college | 389 (42.5) | 552 (40.8) | . |

| College grad/higher | 77 (8.4) | 171 (12.6) | . |

| Employment | <.001 | ||

| Employed/self-employed | 303 (33.0) | 838 (61.8) | . |

| Student | 74 (8.1) | 84 (6.2) | . |

| Out of work | 144 (15.7) | 155 (11.4) | . |

| Unable to work/disabled | 352 (38.3) | 195 (14.4) | . |

| Homemaker | 46 (5.0) | 85 (6.3) | . |

| Yearly income | <.001 | ||

| Less than $10k | 453 (50.2) | 385 (29.3) | . |

| $10,001-$20k | 265 (29.4) | 433 (33.0) | . |

| $20,001-$40k | 137 (15.2) | 332 (25.3) | . |

| More than $40k | 47 (5.1) | 164 (12.5) | . |

| Smoking History | |||

| Cigs/day | 14.7±9.6 | 13.0±8.8 | <.001a |

| Time until 1st cig (mins) | <.001 | ||

| ≤ 5 | 299 (32.2) | 307 (22.5) | . |

| 6 – 15 | 300 (32.3) | 380 (27.8) | . |

| 16 – 30 | 138 (14.9) | 204 (15.0) | . |

| 31 – 60 | 85 (9.2) | 184 (13.5) | . |

| > 60 | 107 (11.5) | 290 (21.3) | . |

| Healthcare Provider | |||

| Regular healthcare provider | 771 (83.6) | 986 (72.5) | <.001 |

| Social Environment | |||

| Friends/family who smoke | <.001 | ||

| Almost all | 239 (25.7) | 240 (17.5) | . |

| Over half | 203 (21.8) | 294 (21.4) | . |

| About half | 201 (21.6) | 397 (28.9) | . |

| Less than half | 126 (13.5) | 212 (15.5) | . |

| Very few | 141 (15.2) | 203 (14.8) | . |

| None | 21 (2.3) | 26 (1.9) | . |

| Support of others for quitting | 4.4±0.8 | 4.5±0.7 | .019a |

| Home smoking rules | <.001 | ||

| Smoking is not allowed | 410 (43.9) | 742 (54.1) | . |

| Smoking is allowed at times | 252 (27.0) | 357 (26.0) | . |

| Smoking is allowed | 271 (29.1) | 273 (19.9) | . |

| Mediators | |||

| Healthcare provider discussed medication | 443 (49.2) | 517 (38.4) | <.001 |

| Healthcare provider discussed other | 378 (42.0) | 488 (36.7) | .007 |

| Healthcare provider bias | 6.0±2.8 | 5.9±2.8 | .26 |

Satterthwaite test

Note: Bold indicates p<0.05.

Cessation Treatment Utilization

SMI was positively associated with cessation treatment utilization (medication, counseling, and any treatment utilization) at 12-month follow-up (Table 2) (Figures 1–3).

Table 2.

Cessation Treatment Utilization of SMI vs Non-SMI Smokers at 12-Month Follow-up

| Outcome | SMI | Non-SMI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | |||

| Treatment Utilization | |||

| Medication | 298/687 (43.4) | 303/1021 (29.7) | <0.001 |

| Counseling | 95/687 (13.8) | 119/1021 (11.7) | 0.184 |

| Any | 315/687 (45.9) | 324/1021 (31.7) | <0.001 |

Note: Bold indicates p<0.05.

Individual Regression Effects

Healthcare Provider-Delivered Advice to Use Medication

In fully adjusted analyses, SMI was not associated with advice to use cessation medication (β1=0.09, p=0.216). Advice to use cessation medication was associated with a greater liklihood of using of medication (β2=0.30, p<0.001) and any treatment (β3=0.25, p=0.004) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of regression effects for advice to use medication mediator

Note: Boldface indicates p<0.05

Healthcare Provider-Delivered Advice to Use Treatments Other Than Products

SMI was not associated with advice to use cessation treatments other than products (β1=0.00, p=0.927). Advice to use treatments other than products was not associated with utilization of counseling (β2=0.13, p=0.372), but was associated with a greater likilhood of utilizing any treatment (β3=0.21, p=0.013) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of regression effects for advice to use other treatments mediator

Note: Boldface indicates p<0.05

Healthcare Provider Bias

SMI was not associated with perceptions of healthcare provider bias (β1=0.11, p=0.405), and healthcare provider bias was not associated with utilization of any treatment (β2=0.00, p=0.933) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Summary of regression effects for perceptions of healthcare provider bias mediator

Note: Boldface indicates p<0.05

Mediation Effects

In fully adjusted analyses, advice to use medication mediated 5.4% of the total effect of SMI on medication utilization and 4.9% of the total effect of SMI on any form of treatment utilization, although neither effect was statistically significant. Advice to use treatments other than products mediated −15.6% of the total effect of SMI on counseling utilization and 5.0% of the total effect of SMI on any form of treatment utilization, although these effects were not statistically significant. Perceptions of healthcare provider bias mediated less than 1% of the total effect of SMI on any form of treatment utilization, which was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mediation Effects for Healthcare Provider Advice and Bias Mediators and Treatment Utilization Outcomes

| Exposure | Mediator | Outcome | Model | Total Effect RR (95% CI) | Direct Effect RR (95% CI) | Indirect Effect RR (95% CI) | Proportion Mediated (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious Mental Illness | Healthcare Provider Advice to Use Medication | Medication utilization | Model 1 | 1.46 (1.29–1.66) | 1.40 (1.24–1.58) | 1.04 (1.02–1.07) | 11.1 |

| Model 2 | 1.35 (1.18–1.55) | 1.32 (1.15–1.51) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 9.3 | |||

| Model 3 | 1.29 (1.12–1.48) | 1.26 (1.10–1.44) | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 7.3 | |||

| Model 4 | 1.30 (1.12–1.50) | 1.28 (1.10–1.48) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 5.3 | |||

| Model 5 | 1.31 (1.14–1.52) | 1.28 (1.13–1.49) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 5.4 | |||

| Any treatment utilization | Model 1 | 1.44 (1.27–1.61) | 1.39 (1.22–1.56) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 10.3 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.31 (1.15–1.49) | 1.28 (1.13–1.46) | 1.02 (1.01–1.05) | 8.9 | |||

| Model 3 | 1.26 (1.10–1.42) | 1.24 (1.08–1.40) | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 6.7 | |||

| Model 4 | 1.26 (1.11–1.43) | 1.24 (1.09–1.40) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 5.3 | |||

| Model 5 | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) | 1.25 (1.10–1.43) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 4.9 | |||

| Healthcare Provider Advice to Use Other | Counseling utilization | Model 1 | 1.15 (0.88–1.46) | 1.13 (0.87–1.44) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 10.2 | |

| Model 2 | 1.02 (0.76–1.32) | 1.01 (0.75–1.30) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 35.4 | |||

| Model 3 | 0.96 (0.71–1.26) | 0.96 (0.71–1.26) | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | −8.8 | |||

| Model 4 | 0.95 (0.73–1.23) | 0.95 (0.72–1.23) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | −12.0 | |||

| Model 5 | 0.97 (0.72–1.28) | 0.97 (0.72–1.27) | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | −15.6 | |||

| Any treatment utilization | Model 1 | 1.44 (1.28–1.63) | 1.42 (1.26–1.60) | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 4.4 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.32 (1.14–1.50) | 1.31 (1.13–1.48) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 3.4 | |||

| Model 3 | 1.26 (1.11–1.44) | 1.25 (1.10–1.44) | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 2.0 | |||

| Model 4 | 1.26 (1.11–1.43) | 1.25 (1.11–1.42) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 5.2 | |||

| Model 5 | 1.26 (1.11–1.43) | 1.25 (1.09–1.42) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 5.0 | |||

| Perceived Healthcare Provider Bias | Any treatment utilization | Model 1 | 1.45 (1.29–1.64) | 1.45 (1.27–1.64) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.0 | |

| Model 2 | 1.34 (1.17–1.51) | 1.34 (1.17–1.51) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.0 | |||

| Model 3 | 1.27 (1.12–1.45) | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.0 | |||

| Model 4 | 1.27 (1.11–1.46) | 1.28 (1.11–1.46) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.0 | |||

| Model 5 | 1.27 (1.11–1.46) | 1.27 (1.11–1.46) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.0 |

Model 1 is adjusted for intervention condition

Model 2 is adjusted for intervention condition and demographics

Model 3 is adjusted for intervention condition, demographics, and smoking history

Model 4 is adjusted for intervention condition, demographics, smoking history, and healthcare

Model 5 is adjusted for intervention condition, demographics, smoking history, healthcare, and social environment

Note: Bold indicates p<0.05.

Discussion

The primary aim of the present study was to assess whether healthcare provider barriers contribute to low rates of cessation treatment utilization among smokers with SMI. Contrary to study hypotheses, smokers with SMI utilized cessation treatments at higher rates than those without SMI and healthcare provider interactions were not strong mediators of this association. However, results also revealed that smokers who received healthcare provider-delivered advice to use cessation treatments at baseline were more likely to use cessation treatments in the next 12-months, regardless of their SMI status. Broadly speaking, healthcare providers played an important role in facilitating the use of cessation resources for socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers enrolled in MHCP.

In general, the meditation effects of the healthcare provider-delivered treatment advice variables were small and not statistically significant after adjusting for confounding factors. It is worth noting that the largest attenuations in these effects occurred after adjusting for demographics, smoking history, and healthcare provider characteristics. This suggests that other explanatory factors like the older average age, increased heaviness of smoking, and greater likelihood of having a regular healthcare provider among those with SMI appear to have partially explained the association between the heightened rates of healthcare provider-delivered treatment advice and higher treatment utilization in this group.

There was also no evidence of mediation by perceptions of healthcare provider bias; a finding that can be attributed to the lack of an association between this variable and cessation treatment utilization. Surprisingly, smokers with SMI reported similar levels of healthcare provider bias as those without SMI. It is possible that, because the vast majority of participants with SMI (nearly 84%) reported having a regular healthcare provider, this increased familiarity may have contributed to these patients feeling more comfortable with their healthcare providers and thus less likely to perceive them as biased.

Although there was no evidence of mediation by healthcare provider factors, examination of the direct associations between healthcare provider-delivered treatment advice and subsequent treatment utilization sheds light on the role that healthcare providers play in the cessation process more generally. Notably, both of the treatment advice variables assessed at baseline were associated with the use of treatments at 12-month follow-up. This suggests that healthcare providers’explanations of the benefits of these treatments and how to properly use them may spur action on the part of the patient. Interestingly, while advice to use treatments other than products was not significantly associated with the use of counseling, this advice variable was strongly associated with the use of any form of treatment. It is possible that there is a carry-over effect of healthcare provider-delivered treatment advice, as discussing one form of cessation treatment may act as a sort of primer for the use of other types of treatments.

The existing literature suggests that participants with SMI have more healthcare provider barriers to cessation treatment utilization than smokers without SMI. In the present study, however, smokers with SMI were more likely to report having someone they considered to be their regular healthcare provider and received higher rates of treatment advice from their healthcare providers than their non-SMI counterparts. This indicates that the MHCP care structure may be providing important benefits for smokers with SMI, underlining the importance of publicly-subsidized insurance programs in facilitating the delivery of cessation care to this vulnerable population. Although Medicaid serves 41% of low-income individuals with mental illness (nearly 7 million people), it is also worth noting that low-income individuals with mental illness are uninsured at nearly double the rate of the general population (19% vs 10.9%).25 In addition, while many states recently expanded Medicaid coverage to include low-income adults up to 138% of the federal poverty level, these efforts were not universally adopted, with 14 states opting out of expanded coverage.25 These gaps in Medicaid coverage suggest that barriers to cessation care are likely still a problem for a significant number of uninsured smokers, particularly those with mental health diagnoses.

The present study has several limitations. Because these data were analyzed as observational there is the potential for unmeasured confounding to bias the effect estimates. In addition, there were missing treatment utilization outcomes data for about 26% of participants, although this missingess did not vary by SMI status. This reduced the power of the analyses and introduced the potential for bias. We were also unable to obtain measures of functional impairment to pair with the mental health diagnoses obtained from the DHS claims data to verify that smokers included in the SMI category were experiencing a high degree of functional life impairment at the time of the surveys. Finally, information about healthcare provide delivery of treatment advice was based on participant self-report, and we lack information about the the sepcific types of healthcare providers that these patients interacted with. Going forward, it would be useful to collect more fine-grained information on patient interactions by provider type in order to gain insight into how to optimize the delivery of cessation care on a system level.

Implications for Behavioral Health

The strong association between healthcare provider-delivered advice to use cessation treatments and subsequent treatment utilization, among smokers with and without SMI, highlights the important role that healthcare providers play in the cessation process. Because this sample of smokers were enrolled in MHCP and had access to reduced cost healthcare, it is difficult to extend these findings to the broader population of socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers who may have more variable access to healthcare. However, the high rates of cessation treatment advice reported by this sample suggest that the expansion of publicly subsidized insurance programs may result in greater rates of treatment utilization among low-income smokers, including those with SMI.

As there may be more far-reaching healthcare barriers for those with mental health disorders,15,16,26–28 it is also important to find additional ways to bolster rates of healthcare provider contact and treatment engagement for these smokers. Given the time limitations faced by healthcare providers, it may be necessary to have systems in place to efficiently provide these smokers with referrals to both internal and external cessation resources. More widespread implementation of tobacco treatment specialists within healthcare systems is one approach to improving patient access to these resources. Integration of mental health care and smoking cessation resources is another promising approach to facilitating access to cessation care.29 Going forward, it will be critical to continue to support and improve systems that connect smokers with mental health disorders with the professional support they need in order to achieve long-term abstinence. Given the ongoing threats to Medicaid expansion and overall funding levels, it is similarly important to continue engaging in research that highlights the vital contributions of publically-subsidized insurance programs to behavioral health.

Acknowledgments:

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis VA Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, et al. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67(2):53–59. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6702a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gfroerer J, Dube SR, King BA, et al. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness - United States, 2009–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(5):81–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lo CC, Cheng TC. Race, unemployment rate, and chronic mental illness: a 15-year trend analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2014;49(7):1119–1128. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0844-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence D, Hafekost J, Hull P, et al. Smoking, mental illness and socioeconomic disadvantage: analysis of the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:462. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker A, Richmond R, Haile M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention among people with a psychotic disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1934–1942. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallagher SM, Penn PE, Schindler E, et al. A comparison of smoking cessation treatments for persons with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(4):487–497. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers ES, Fu SS, Krebs P, et al. Proactive Tobacco Treatment for Smokers Using Veterans Administration Mental Health Clinics. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018;54(5):620–629. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George TP, Vessicchio JC, Sacco KA, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion combined with nicotine patch for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63(11):1092–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stapleton JA, Watson L, Spirling LI, et al. Varenicline in the routine treatment of tobacco dependence: a pre-post comparison with nicotine replacement therapy and an evaluation in those with mental illness. Addiction. 2008;103(1):146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown RA, Niaura R, Lloyd-Richardson EE, et al. Bupropion and cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(7):721–730. doi: 10.1080/14622200701416955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall SM, Muñoz RF, Reus VI, et al. Mood management and nicotine gum in smoking treatment: a therapeutic contact and placebo-controlled study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(5):1003–1009. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35(2):158–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown CH, Medoff D, Dickerson FB, et al. Factors influencing implementation of smoking cessation treatment within community mental health centers. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2015;11(2):145–150. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2015.1025025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hitsman B, Moss TG, Montoya ID, et al. Treatment of tobacco dependence in mental health and addictive disorders. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;54(6):368–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lester H, Tritter JQ, Sorohan H. Patients’ and health professionals’ views on primary care for people with serious mental illness: focus group study. BMJ. 2005;330(7500):1122. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38440.418426.8F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrigan PW, Mittal D, Reaves CM, et al. Mental health stigma and primary health care decisions. Psychiatry Research. 2014;218(1–2):35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu SS, van Ryn M, Burgess DJ, et al. Proactive tobacco treatment for low income smokers: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:337. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu SS, Van Ryn M, Nelson D, et al. Proactive tobacco treatment offering free nicotine replacement therapy and telephone counselling for socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers: A randomised clinical trial. Thorax. 2016. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.University of San Diego. California tobacco surveys. http://libraries.ucsd.edu/locations/sshl/data-gov-info-gis/ssds/guides/tobacco-surveys.html. Published 2010. Accessed February 11, 2009.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. 2010.

- 21.Davis RM. Healthcare report cards and tobacco measures. Tobacco Control. 1997;6 Suppl 1:S70–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(2):101–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30262.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychological Methods. 2013;18(2):137–150. doi: 10.1037/a0031034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robins JM, Greenland S. Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 1992;3(2):143–155. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199203000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser Family Foundation. Facilitating Access to Mental Health Services: A Look at Medicaid, Private Insurance, and the Uninsured.; 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Fact-Sheet-Facilitating-Access-to-Mental-Health-Services-A-Look-at-Medicaid-Private-Insurance-and-the-Uninsured. Accessed March 14, 2019.

- 26.Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28(2):145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones S, Howard L, Thornicroft G. “Diagnostic overshadowing”: worse physical health care for people with mental illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2008;118(3):169–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFall M, Saxon AJ, Malte CA, et al. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2485–2493. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]