Abstract

Objective:

To examine longer-term effects of behavioral weight loss (BWL) and Stepped Care for binge-eating disorder (BED) and obesity through 12-month follow-up after completing treatments.

Method:

191 patients with BED/obesity were randomized to six-months of BWL (N=39) or Stepped Care (N=152). Within Stepped Care, patients began BWL (one month), treatment-responders continued BWL, non-responders switched to cognitive-behavioral therapy, and all were randomized (double-blind) to weight-loss medication or placebo (five months). Patients were independently assessed throughout/after treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

Results:

ITT analyses of remission rates revealed BWL and Stepped Care did not differ significantly at post-treatment (74.4% vs 66.5%), 6-month (38.2% vs. 33.3%), or 12-month (44.7% vs 41.0%) follow-ups. Mixed-models of binge-eating frequency indicated significant reductions through post-treatment, but no significant changes nor differences between BWL and Stepped Care during follow-up. Mixed-models revealed significant weight-loss with no differences between BWL and Stepped Care (5.1% vs 5.8%) at post-treatment and significant time effects (larger percent weight-loss at 6- than 12-month follow-ups) that did not differ between BWL and Stepped Care (−5.1% vs −5.2% and −3.4% vs −5.0%, respectively).

Conclusions:

Binge-eating improvements and weight losses produced by BWL and adaptive Stepped Care did not differ significant 12 months after completing treatments.

Keywords: obesity, eating disorders, treatment, binge eating, weight loss, maintenance

Introduction

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is defined by recurrent binge-eating behaviors, marked distress, but without inappropriate weight-compensatory behaviors that characterize other eating disorders (1). BED, the most prevalent eating disorder among adults, occurs in men and women, across ethnic/racial groups, and throughout adulthood (2). BED is associated strongly with obesity (3) and is associated with increased risk for psychiatric and medical comorbidities and serious psychosocial impairments (2–4). BED shows distinct psychopathologic and neurobiological features from obesity (5,6).

Despite BED’s high biopsychosocial burden, many persons with BED never receive treatment for this condition, let alone treatments with a supporting evidence base (7). Randomized controlled trials (RCT) for BED have reported empirical support for specific psychological treatments (8), such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and behavioral weight loss (BWL) (9), and certain pharmacological agents (10,11). To date, even following “best-available” treatments, a substantial proportion of patients with BED do not achieve abstinence from binge eating or lose weight (12). Indeed, weight losses in treatment studies for BED have consistently been dampened relative to those for obesity without BED (13); producing greater weight losses alongside comparable reductions in binge eating is one possible advantage for BWL over CBT (9). To date, nearly all RCTs combining pharmacological and psychological approaches have failed to report enhanced outcomes for BED (14) which highlights the pressing need for more complex approaches for treating BED (12).

Grilo and colleagues (15) recently reported acute outcomes from an adaptive “sequential multiple assignment randomized trial” (SMART) (16,17) that evaluated an innovative treatment model for patients with BED with co-existing obesity. The adaptive treatment design was built on reliable findings that rapid response to treatments for BED has robust prognostic significance (18,19,20) and, importantly, that rapid response specifically to BWL predicts superior reductions in both binge eating and weight (21,22). In the Grilo et al (15) RCT, participants were randomized to either BWL or to Stepped Care for 6 months. Within Stepped Care, following one month of BWL, patients were then stratified by whether or not they had a “rapid response” to BWL. Rapid responders were then randomized to receive either weight-loss medication (sibutramine or orlistat) or placebo in addition to continuing BWL for 5 months. Participants without a rapid response to BWL were switched to CBT and additionally randomized to also receive either weight-loss medication or placebo. Overall, BWL and Stepped Care both produced robust improvements in binge eating (74.4% and 66.5% remission rates, respectively) and weight loss (5.1% and 5.8%) and within Stepped Care, weight-loss medications enhanced outcomes.

The aim of this study was to extend our initial report of acute outcomes of BWL and Stepped Care (15) by examining their longer-term effects during 12-month follow-ups after having completed treatments (i.e., 18 months after baseline). Secondary aims were to explore (double-blind), within Stepped Care, the longer-term outcomes for weight-loss medication conditions after completing treatments and discontinuing medications; this goal addresses a major gap (i.e., dearth of pharmacotherapy follow-up data) in the BED treatment literature (23,24).

Methods

Participants

Participants were 191 consecutively assessed patients recruited via media advertisements for treatment studies for BED at a medical-school program (2008–2012). Eligibility criteria included age between 18 and 65 years, body mass index (BMI) between 30 and 50 kg/m2, and DSM-IV-defined BED. Exclusion criteria were minimal for this effectiveness RCT and were clinical issues necessitating different treatments or representing contraindications to the study medications. Exclusionary criteria were: on-going eating/weight treatments, taking contraindicated medications, uncontrolled medical problems (e.g., diabetes, thyroid dysfunction) that impact eating/weight or contraindications to study medications (e.g., cardiovascular disease, blood pressure >160/95 mmHg, or resting heart rate >100 beats/minute); and pregnancy or not using reliable birth control. The study received approval by the Yale IRB and all participants provided written informed consent.

The 191 randomized participants had a mean age of 48.4 (SD=9.5) years, mean BMI of 39.0 (SD=6.0) kg/m2; 71% (N=136) were female, 84% (N=160) attended/finished college, and 79% (N=150) were White, 15% (N=28) were African-American, 4% (N=8) Hispanic, and 2% (N=5) “other” ethnicity/race.

Diagnostic Assessments and Repeated Outcome Measures

Trained doctoral research-clinicians performed the diagnostic and assessment interviews at baseline and throughout the study (blinded to treatment; see below). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P; 25) was administered to determine BED as well as co-existing psychiatric disorders (reported in (15)). Eating Disorder Examination Interview (EDE-16th edition; 26) was administered to confirm the SCID-based BED diagnosis and to characterize eating-disorder psychopathology at baseline, post-treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. The EDE, which focuses on the previous 28 days (except for diagnostic items rated for DSM-based duration criteria), assesses the frequency of objective binge-eating episodes (OBE) and also comprises four subscales of eating-disorder psychopathology which are averaged for a total global score reflecting severity. The EDE demonstrates good validity (27) and inter-rater and test-retest reliability in studies with BED (28). In this study, inter-rater (N=37) intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) were 0.86 for binge-eating frequency and 0.94 for the EDE global score.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; 29), a 21-item psychometrically-sound self-report measure of depression symptoms/levels (30) was completed at baseline, monthly, post-treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. In this study, coefficient alpha for the BDI was 0.90.

Weight and height were measured at baseline and weight was measured at post-treatment and at follow-ups using a large-capacity digital scale. Waist circumference was measured following NHBLI (31) protocol as a proxy for excess abdominal fat, which predicts cardiovascular risk (32).

Treatment Conditions

Treatments were delivered by trained research-clinicians (by C.M.G.) who were monitored throughout the study to maintain adherence to protocols. Masters-level clinicians delivered “generalist” BWL, doctoral-level clinicians delivered “specialist” CBT, and a faculty-level psychiatrist delivered pharmacotherapy with minimal clinical management. The study’s treatments were closely matched in terms of total sessions and time to minimize potential confounds due to “differences in attention.” The BWL (Standard) treatment comprised 16 sessions and Stepped Care comprised 15 sessions (of either BWL or 4 sessions of BWL followed by 11 sessions of CBTgsh) plus additional time for pharmacotherapy sessions involving minimal clinical management to collectively result in comparable overall total time to the BWL (Standard) treatment.

Behavioral Weight Loss (BWL).

The same manualized protocol was followed in the BWL (Standard) and the BWL treatment within Stepped-care. BWL was based on the LEARN Program for Weight Management (33) and since updated and refined for RCTs with BED (9) and obesity (34). BWL was delivered in individual sessions ranging 50–60 minutes following the manual and keyed to specific patient readings in their copy of the self-care manual and to weekly behavioral goals. BWL focuses on making gradual behavioral lifestyle changes, moderate caloric reductions with improved nutrition quality (1200–1500 kcal/day, less than 30% fat), and moderate increases in physical activity (30 minutes physical activity five times weekly). Behavioral strategies include goal setting, recording food intake and physical activity, and problem-solving to cope with barriers to attaining goals.

Cognitive-behavioral Therapy by Guided-Self-Help (CBTgsh).

CBTgsh followed manualized protocols used previously (35–37) in RCTs for BED. CBTgsh followed manualized sessions (11 individual sessions ranging 25–30 minutes) reinforcing the self-care manual provided to patients. CBTgsh comprises six steps designed to assess and modify eating behaviors and to address cognitive features (such as the over-importance assigned to shape/weight) hypothesized to maintain the disordered eating. Clinicians “guide” the CBTgsh by addressing questions about the CBT model and program, assisting with difficulties performing the behavioral steps and cognitive-restructuring exercises, and reinforcing the importance of self-monitoring, record keeping, and goal-setting.

Medication (Weight-loss Medication or Placebo).

Pharmacotherapy was delivered double-blind (matched identical capsules) with minimal clinical management. There were no FDA-approved medications for BED when the study was started and of the FDA-approved weight-loss medications at the time, sibutramine was selected because it had been shown to reduce both binge eating and weight in RCTs with BED (38) and to enhance weight losses for obesity (34). Sibutramine, a serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, was given using 15 mg per day fixed-doses (38) during the last five months of Stepped Care. When sibutramine was withdrawn from the market (October 2010), the study was continued as conceptually designed by using the FDA-approved weight-loss medication orlistat (39), which had some empirical support for BED (36). Orlistat, a lipase inhibitor, was given using 120mg three-times-daily dosing (39).

Treatment Randomization and Blind Assessment Protocol

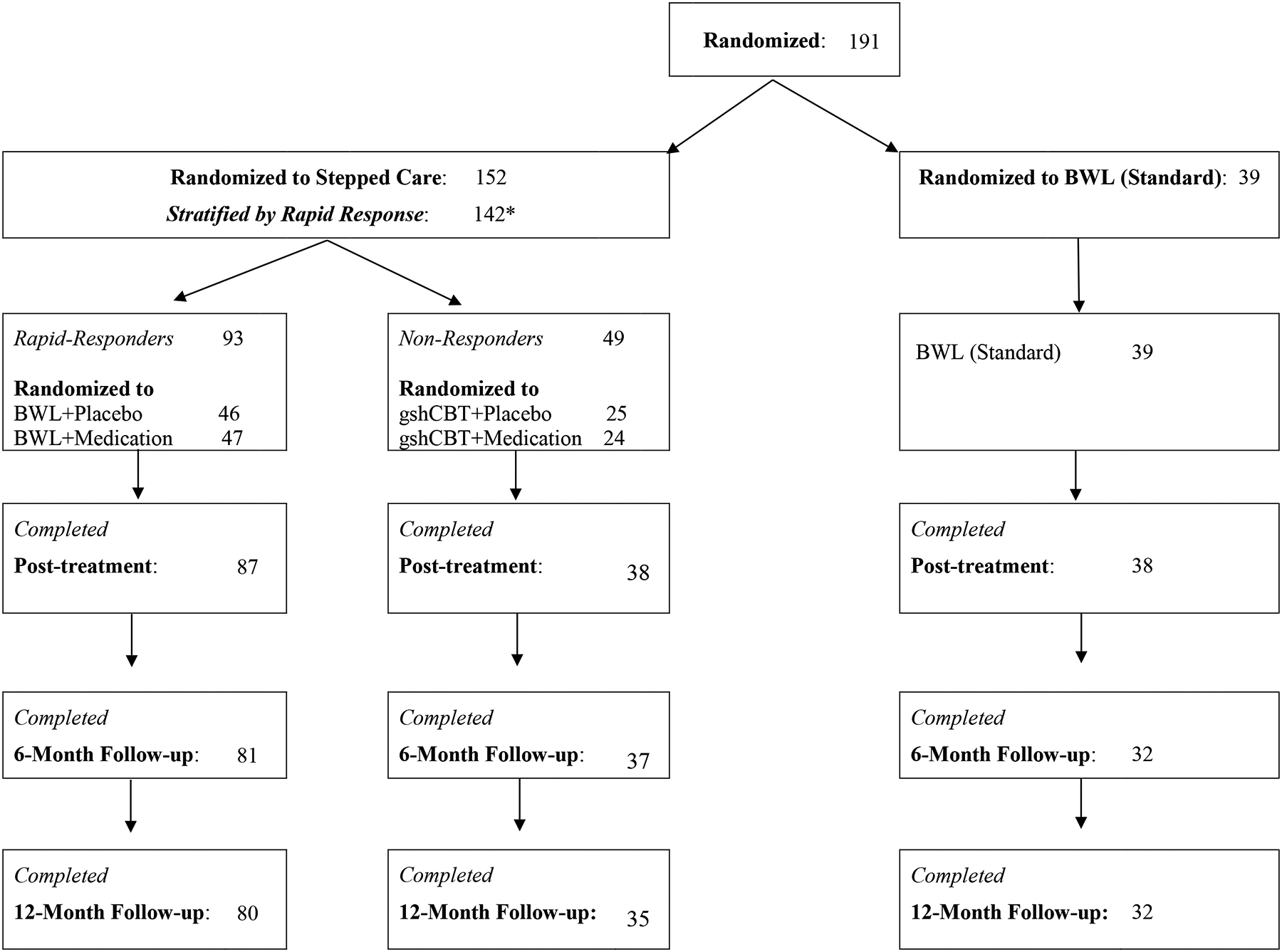

Figure 1 shows the RCT design which included three different randomization schedules described previously (15). Briefly, first randomization followed a ratio of 4:1 to Stepped-care or BWL (Standard). Within Stepped Care, rapid responders continued with BWL plus were block-randomized to also receive either weight-loss medication or placebo (1:1 ratio) in double-bind fashion. Non-rapid responders were switched to CBTgsh and were block-randomized to also receive (double-blind) either weight-loss medication or placebo (1:1 ratio). Block sizes (to protect the blind), varied between 10 and 15 for the initial randomization and between 4 and 6 for the subsequent randomizations.

Figure 1. Flow of participants throughout study.

Note. *In Stepped Care, N=10 were not stratified (thus yielding N=142) because they were either withdrawn (n=1 due to pregnancy) or dropped out (n=4 due to time commitment, n=1 due to relocating out of state, n=1 due to dissatisfaction with weight loss, and n=3 for unknown reasons).

Randomization schedule, developed by biostatistician, was implemented by independently by Yale Investigational Drug Service and treatment assignments were kept blind from participants until starting treatments. Study medications were provided in identical-appearing capsules (in matching “dosing”) to conceal double-blind. Independent assessors performing outcome evaluations were also kept blinded with respect to whether participants had received BWL or Stepped Care and whether any study medication was received.

Statistical Analyses

Power calculations yielded a target sample size of N=175 (allocated in 4:1 ratio for Stepped Care versus BWL (Standard)) to have 80–85% power to detect medium effect sizes (Cohen’s d=0.57) for main outcomes at two-sided alpha level of 0.05 (Grilo et al., 2020).

All analyses designed to compare treatments were “intent-to-treat” (ITT) performed for all N=191 randomized patients for the primary (Stepped Care versus BWL (Standard)) and secondary comparisons (within Stepped Care). We examined whether there were differences between Stepped Care and BWL, whether there were any differences among the treatments within Stepped Care and whether the averages for the weight-loss medication conditions differed from the averages for the placebo during the follow-up period.

Primary outcome variables were binge eating (analyzed categorically as remission and continuously as frequency) and weight loss (calculated as percent weight loss from baseline). “Remission” from binge eating was defined as zero binges during the previous 28 days (OBEs assessed by EDE interview). Secondary outcomes included eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE interview Global Score), depression (BDI score), and waist circumference.

Chi-square tests compared treatment groups on remission rates for the entire N=191 ITT sample at post-treatment, 6-months and at 12-month follow-up. In instances of treatment dropout or missing data, non-remission was imputed. All other outcomes were analyzed using mixed effects regression models with all available data during follow-up on an individual. Treatment condition was specified as group (Stepped Care vs. BWL (Standard)), medication (Med vs Pla) or cell (BWL+Med, BWL+Pla, CBTgsh+Med, CBTgsh+Pla), in separate models. In each model, treatment was a between-subject factor, time (6-month, 12-month) was a within-subject factor and the corresponding outcome at post-treatment was included as a covariate. Outcomes that did not conform to normality were log-transformed prior to analysis. The best-fitting variance-covariance structure in each model was selected using Schwartz-Bayesian criterion (BIC). Significant interactions and main effects were explained by performing tests of simple effects and/or pairwise comparisons.

Results

Randomization and Participant Flow Through Study

Figure 1 shows flow of participants through the study. Total of N=191 were randomized (4:1 ratio) to either Stepped Care (N=152) or BWL (Standard) (N=39). The treatment groups did not differ significantly on any demographic, psychiatric, or pretreatment levels of outcome variables (Grilo et al., 2020). Within Stepped Care, N=142 were stratified by rapid response after one month (N=93 categorized with rapid response and 49 without) of which N=71 were randomized to placebo and N=71 to active medication (the first N=38 to sibutramine and the next N=33 to orlistat). Within Stepped Care, N=10 were not stratified (thus yielding N=142) because they were either withdrawn (n=1 due to pregnancy) or dropped out (n=4 due to time commitment, n=1 due to job relocation, n=1 due to dissatisfaction with weight, and n=3 for unknown reasons). Stepped-care and BWL (Standard) treatments did not differ significantly in number of sessions attended (mean = 13.1, 13.3, respectively) nor did the specific treatments within Stepped-care (range 12.2 to 14.7). Outcome assessments were successfully completed for: 90% (N=171/191) of post-treatment, 82% (156/191) of 6-month follow-ups, and 80% (153/191) of 12-month follow-ups; rates did not differ between Stepped Care and BWL (Standard).

Binge-Eating Outcomes

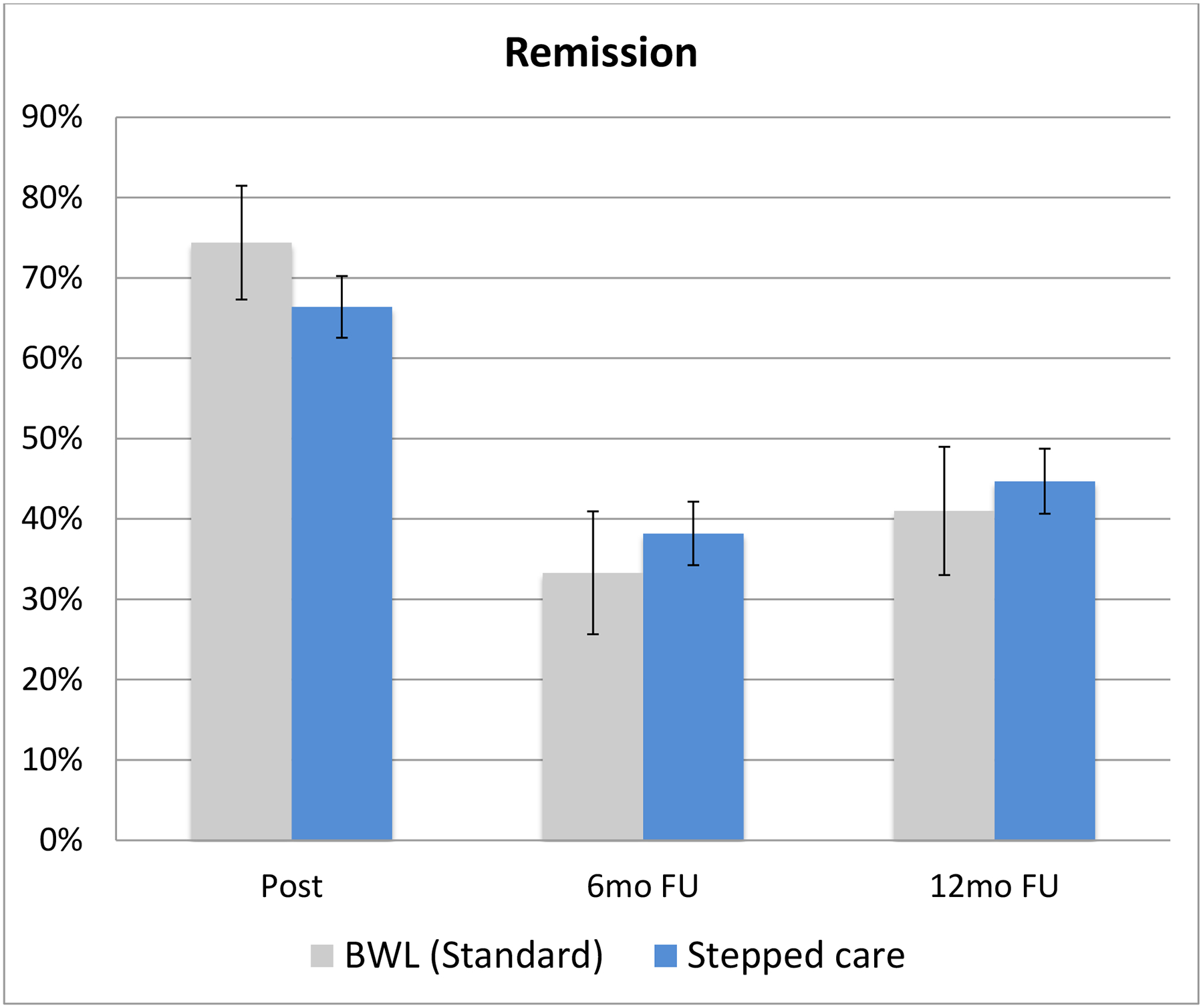

Figure 2 shows binge-eating remission rates for Stepped Care and BWL (Standard) for ITT analyses with all randomized patients (missing data coded as failure to remit) across the follow-up assessments. Binge-eating remission for Stepped Care (66.5%) and BWL (Standard) (74.4%) did not differ significantly (χ2 (1)=0.89, p=0.34) at post-treatment, at the 6-month follow-up (38.2%, 33.3%, respectively; χ 2 (1)=0.31, p=0.58), or at the 12-month follow-up (44.7%, 41.0%, respectively; χ2 (1)=0.17, p=0.68).

Figure 2. Binge-eating remission rates for BWL (Standard) and Stepped Care across follow-up assessments.

Percentage of participants in the two overall acute treatment conditions (BWL (Standard) and Stepped Care)) who achieved remission from binge eating at post-treatment, 6-month follow-up, and 12-month follow-up assessments. Remission is defined as zero binge-eating episodes for the previous month based on the Eating Disorder Examination Interview. Intent-to-treat analysis for all randomized participants (n=191) with instances of missing data coded as non-remission. Note: BWL = behavioral weight loss.

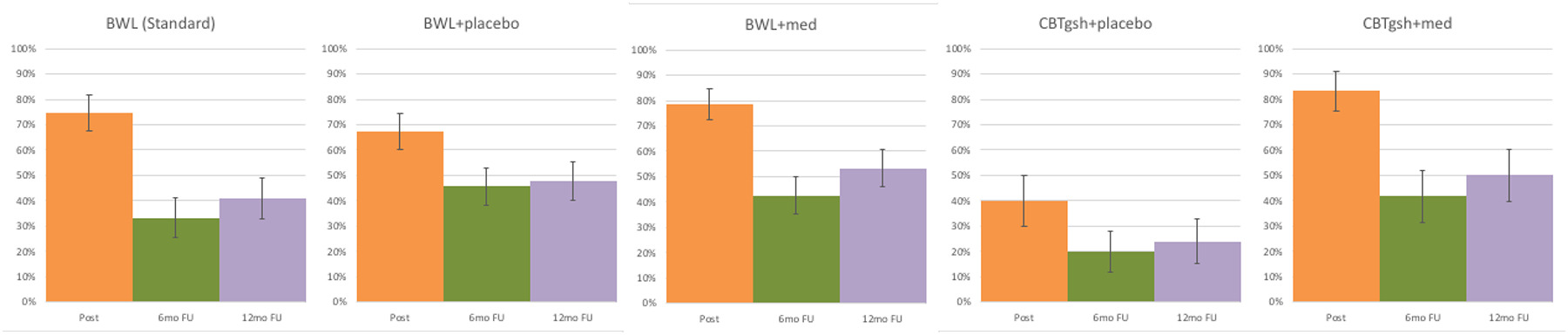

Figure 3 shows binge-eating remission rates within the Stepped-care conditions (alongside those for BWL (Standard) for context) across the follow up assessments. Analysis of remission rates within Stepped Care at post-treatment (which ranged 40.0% – 83.3%) revealed significant differences (χ2 (3)=14.27, p=0.003) at post-treatment. Analysis of remission rates at 6-month follow-up (range 20.0% – 45.7%) were not significant (χ 2 (3)=4.94, p=0.18) nor were remission rates at 12-month follow-up (range 24.0% – 53.2%) (χ2 (3)=6.07, p=0.11).

Figure 3. Binge-eating remission rates for BWL (Standard) and for the four arms within Stepped Care across follow-up assessments.

Percentage of participants in BWL (Standard) and in the four arms within Stepped Care who achieved remission from binge eating at post-treatment, 6-month follow-up, and 12-month follow-up assessments. Remission is defined as zero binge-eating episodes for the previous month based on the Eating Disorder Examination – Interview. Intent-to-treat analysis for all randomized participants with baseline carried forward method for instances of missing data (i.e., missing data coded as non-remission).

Note: BWL = behavioral weight loss; CBTgsh = cognitive-behavioral therapy via guided self-help; Med = weight-loss medication

Tables 1 and 2 summarize binge-eating frequency for Stepped Care and BWL (Standard) and within Stepped Care, respectively, across the follow-up assessments. As context for the post-treatment through follow-up analyses in this current report, we note the following post-treatment findings for binge-eating frequency. Mixed models analyses revealed overall significant improvement from baseline to post-treatment across conditions (F(1,172)=556.75, p<.0001) but not significant differences between Stepped Care and BWL (Standard) (F(1,172)=0.86, p=0.36). Analyses within Stepped care indicated a significant treatment-by-time interaction (F(4,168)=3.62, p=0.01), significant time (F(1,170)=794.22, p<.0001), and significant treatment (F(4,170)=4.12, p=0.003) main effects. Within Stepped Care, medication was associated with significantly greater reduction in binge-eating frequency than placebo (F(1,172)=7.00, p=0.01). Within rapid responders continuing BWL, medication was not significantly different from placebo (F(1,164)=0.13, p=0.72); however, within non-rapid responders to BWL switched to CBTgsh, medication was associated with significantly greater reductions in binge-eating than placebo (F(1,175)=8.65, p=0.004). At post-treatment, the conditions differed significantly (F(4,157)=4.71, p=0.001); within Stepped care, medication groups had lower binge-eating frequency than placebo (F(1,157)=14.93, p=0.0002) and adding medication to CBTgsh was associated with lower binge-eating frequency than adding placebo (F(1,157)=16.53, p<.0001).

Table 1.

Clinical Variables Across Treatment Groups at Post-treatment and 6- and 12-Month Follow-ups.

| Post-treatment | 6-Month Follow-up | 12-Month Follow-up | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Care | Stepped Care | Standard Care | Stepped Care | Standard Care | Stepped Care | |||||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| OBE/month (EDE) | 1.7 | (2.3) | 2.7 | (8.1) | 1.9 | (2.8) | 3.8 | (7.1) | 2.4 | (3.8) | 2.4 | (5.0) |

| Global Score (EDE) | 1.8 | (0.9) | 1.8 | (0.9) | 1.7 | (1.1) | 1.7 | (0.9) | 1.7 | (1.0) | 1.6 | (0.9) |

| Depression (BDI) | 10.0 | (9.3) | 8.9 | (7.8) | 9.1 | (9.3) | 8.8 | (7.4) | 9.4 | (8.4) | 8.2 | (8.1) |

| Body mass index | 35.7 | (6.1) | 36.9 | (5.8) | 35.2 | (6.7) | 37.3 | (6.7) | 35.9 | (6.6) | 37.3 | (6.8) |

| Weight | 215.6 | (43.9) | 229.3 | (46.5) | 208.1 | (45.8) | 234.4 | (51.4) | 217.8 | (47.0) | 234.0 | (51.0) |

| % Wt Loss from Base | −5.1 | (5.4) | −5.8 | (7.1) | −5.1 | (7.0) | −5.2 | (9.7) | −3.4 | (7.0) | −5.0 | (10.3) |

| % Wt Loss from Post | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.4 | (4.2) | 0.8 | (6.2) | 1.3 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 8.2 |

| Waist Circumference | 41.6 | (5.5) | 43.6 | (5.8) | 40.8 | (5.7) | 44.1 | (6.2) | 41.8 | (5.4) | 44.2 | (6.1) |

Note: M = mean; SD = standard deviation. EDE = eating disorder examination interview; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; Wt = weight

Table 2.

Clinical Variables Across the Four Treatments Within the Stepped Care Treatment Group.

| Post-treatment | 6-month follow-up | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWL+Pla | BWL+Med | CBT+Pla | CBT+Med | BWL+Pla | BWL+Med | CBT+Pla | CBT+Med | |||||||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Binge episodes/month (EDE) | 1.7 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 6.2 | 9.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 5.9 | 3.3 | 5.7 | 9.9 | 11.4 | 1.9 | 3.4 |

| EDE Global Score | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.8 |

| Depression (BDI) | 7.9 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 5.7 | 15.1 | 13.4 | 7.4 | 4.9 | 8.4 | 6.2 | 7.0 | 6.4 | 14.1 | 10.5 | 6.9 | 5.1 |

| Body mass index | 37.1 | 5.5 | 34.9 | 5.5 | 40.6 | 5.6 | 36.3 | 5.0 | 37.9 | 7.0 | 35.0 | 6.6 | 40.6 | 5.8 | 37.3 | 5.4 |

| Weight | 230.8 | 50.0 | 215.2 | 38.5 | 257.5 | 49.5 | 233.7 | 40.3 | 234.5 | 54.9 | 219.8 | 49.1 | 260.8 | 49.5 | 240.0 | 41.2 |

| % Wt Loss from Base | −6.1 | 5.9 | −8.6 | 7.0 | −0.5 | 5.7 | −4.6 | 8.4 | −5.3 | 9.2 | −8.2 | 10.2 | −0.3 | 5.0 | −2.9 | 12.1 |

| % Wt Loss from Post | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.1 | 6.5 | 1.3 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 5.7 |

| Waist Circumference | 43.6 | 5.9 | 41.9 | 4.8 | 47.4 | 6.5 | 43.4 | 5.4 | 44.2 | 6.3 | 42.3 | 6.0 | 47.4 | 6.7 | 44.3 | 5.0 |

| 12-month follow-up | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWL+Pla | BWL+Med | CBT+Pla | CBT+Med | |||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Binge episodes/month (EDE) | 2.2 | 5.0 | 2.7 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| EDE Global Score | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| Depression (BDI) | 7.2 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 5.5 | 16.5 | 13.3 | 6.3 | 6.5 |

| Body mass index | 38.1 | 7.3 | 34.6 | 6.5 | 40.8 | 5.9 | 37.1 | 5.3 |

| Weight | 236.5 | 56.4 | 218.3 | 47.2 | 261.9 | 48.2 | 233.9 | 43.8 |

| % Wt Loss from Base | −6.3 | 9.8 | −7.6 | 10.6 | 0.2 | 6.0 | −2.3 | 12.7 |

| % Wt Loss from Post | −0.1 | 8.4 | 2.6 | 9.3 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 7.5 |

| Waist Circumference | 44.1 | 6.3 | 42.6 | 6.0 | 47.9 | 6.2 | 43.8 | 5.3 |

Note: M = mean. SD = standard deviation. EDE = Eating Disorder Examination. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; Wt = Weight Within Stepped-care, the following specific treatment cells were created by the stratified randomization: BWL+Pla (N=46), BWL+Med (N=47; of these, N=22 with sibutramine and N=25 with orlistat), CBTgsh+Pla (N=25), and CBTgsh+Med (N=24; of these, N=16 with sibutramine and N=8 with orlistat).

For the follow-up period, mixed models analyses of binge-eating frequency (log transformed values) revealed that post-treatment and follow-up frequencies were significantly associated with each other (F(1,154)=67.16, p<.0001) but indicated that Stepped Care and BWL (Standard) did not differ significantly (F(1,156)=0.42, p=0.51), nor were there significant effects of time (F(1,149)=1.84, p=0.18) or treatment-by-time interactions (F(1,149)=1.61, p=0.21). Within Stepped Care, post-treatment and follow-up frequencies of binge eating were significantly associated (F(1,116)=41.45, p<.0001) and there was a significant effect of time (F(1,109)=5.69, p=0.02) with binge eating frequencies lower at 12-month than at 6-month follow-up; medication and placebo groups did not differ significantly (F(1,112)=0.28, p=0.60) and there was no significant interaction between treatment and time ((F(1,109)=1.09, p=0.30). Overall there were no differences among the four specific treatments within Stepped Care (F(3,111)=0.86, p=0.46) and no significant interactions between treatment and time (F(3,106)=1.18, p=0.32).

Percent Weight Loss

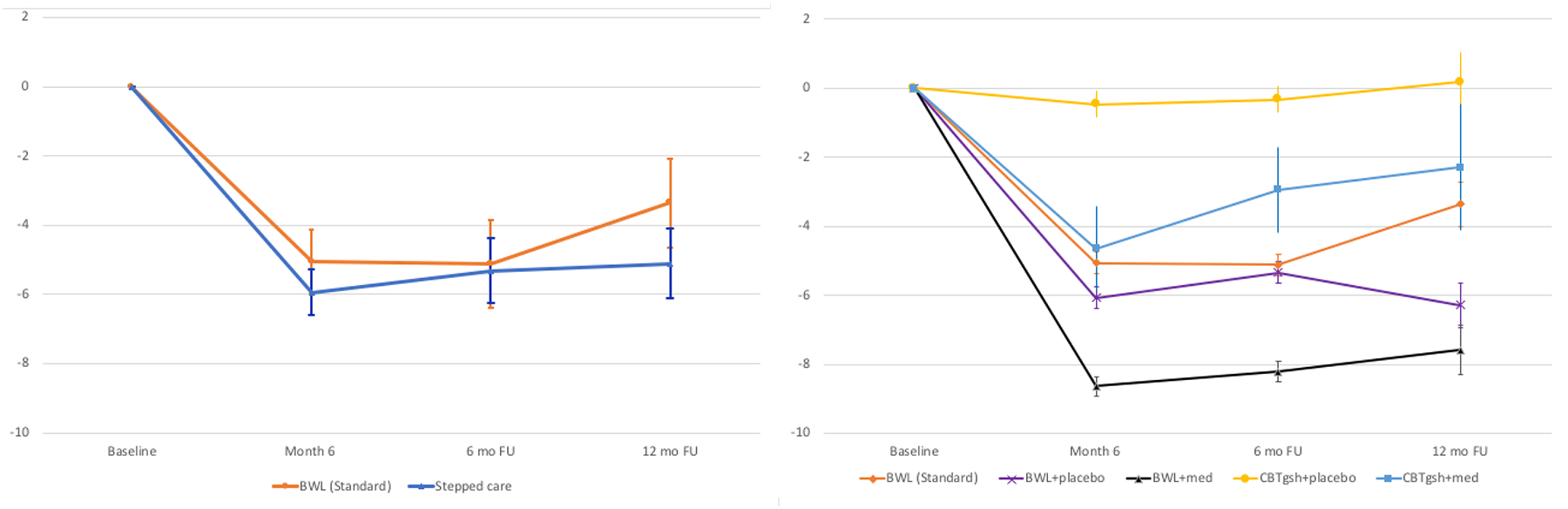

Figure 4 shows percent weight loss from baseline to post-treatment and during follow-up across the different treatment conditions (see Tables 1 and 2 for weight and BMI values, in addition to percent weight loss values calculated from both baseline and from posttreatment). As context for the post-treatment through follow-up analyses in this current report, we note the following post-treatment findings for acute weight losses. Mixed models indicated significant percent weight losses (F(5,139)=22.98, p<.0001) but not significant differences between Stepped Care (5.8%) and BWL (5.1%) (F(1,183)=0.05, p=0.83). Within Stepped Care, mixed models indicated significant treatment-by-time interaction (F(20,152)=2.51, p<0.0009), significant time (F(5,136)=36.12, p<.0001), and significant treatment (F(4,178)=7.37, p<.0001) main effects; the addition of medication had significantly greater percent weight loss than adding placebo at post-treatment (p<.0001) and percent weight losses ranged from −0.3 to −8.1.

Figure 4. Percent weight loss for BWL (Standard) and Stepped Care throughout treatment and follow-up assessments.

Left panel shows overall percent weight loss from baseline for BWL (Standard) and Stepped Care.

Right panel shows overall percent weight loss from baseline for BWL (Standard) condition and for the four arms within Stepped Care.

Note: BWL = behavioral weight loss; CBTgsh = cognitive-behavioral therapy via guided self-help; Med = weight-loss medication.

For the follow-up period, mixed models indicated a significant main effect of time (F(1,139)=4.23, p=0.04) and a significant effect of post-treatment weight loss (F(1,145)=470.27, p<.0001); percent weight loss was larger at 6-month than at 12-month follow-up. Stepped Care and BWL (Standard) groups did not differ significantly (F(1,146)=0.36, p=0.55) nor was there a significant treatment-by-time interaction (F(1,139)=1.47, p=0.23). Within Stepped Care, only post-treatment and follow-up percent weight loss values were significantly associated with each other (F(1,109)=381.67, p<.0001); medication and placebo groups did not differ significantly (F(1,112)=3.72, p=0.06) and there was no significant interaction between treatments and time (F(1, 102)=2.82, p=0.10). The four specific treatments within Stepped Care did not differ overall (F(3,109)=1.42, p=0.24) and there was no interaction between treatment and time (F(3,100)=1.25, p=0.30).

Secondary Outcomes: Eating-Disorder Pathology, Depression, and Waist Circumference

Tables 1 and 2 summarize secondary outcomes of eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE Global Score), depression (BDI), and waist circumference across treatments. As context for the post-treatment through follow-up analyses we note the following post-treatment findings. Mixed models indicated significant reductions in EDE global scores (F(1,171)=133.42, p<.0001), BDI scores (F(4,522)=11.83, p<.0001), and waist circumference (F(1,162)=106.03, p<.0001), but no significant differences between Stepped Care and BWL (Standard) in these outcomes.

For the follow-up period, mixed models of eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE Global Score) revealed that post-treatment and follow-up values were significantly associated (F(1,154)=210.25, p<.0001) but indicated that the Stepped Care and BWL (Standard) groups did not differ significantly (F(1,154)=1.83, p=0.18), nor were there significant effects of time (F(1,147)=0.89, p=0.35) or treatment-by-time interactions (F(1,147)=0.17, p=0.68). Within Stepped-care, only post-treatment and follow-up scores were significantly associated (F(1,113)=136.66, p<.0001); there was no significant effect of time (F(1,105)=1.34, p=0.25); medication and placebo groups did not differ (F(1,109)=0.57, p=0.45) and there was no significant interaction between treatment and time (F(1,105)=1.05, p=0.30). The four specific treatments within Stepped Care did not differ overall (F(3,107)=0.89, p=0.45) and there was also no significant interaction between treatment and time interaction (F(3,103)=0.77, p=0.51).

For the follow-up period, mixed models of depression (BDI) scores (log transformed) revealed that post-treatment and follow-up values were significantly associated (F(1,153)=193.42, p<.0001) but indicated that the Stepped Care and BWL (Standard) groups did not differ significantly (F(1,156)=0.40, p=0.53), nor were there significant effects of time (F(1,148)=0.07, p=0.79) or treatment-by-time interactions (F(1,148)=2.59, p=0.11). Within Stepped-care, post-treatment and follow-up scores were significantly associated (F(1,114)=132.19, p<.0001), there was a significant effect of medication (F(1,115)=4.69, p=0.03) with medication having lower BDI scores at follow-up but no significant interaction between medication and time (F(1,109)=2.26, p=0.14). The four specific treatments within Stepped Care did not differ significantly overall (F(3,112)=1.73, p=0.16) and there was no significant interaction between treatment and time (F(3,107)=2.32, p=0.08).

For the follow-up period, mixed models of waist circumference revealed that post-treatment and follow-up values were significantly associated (F(1,148)=716.77, p<.0001) and a significant time effect (F(1,139)=4.50, p=0.04) with larger waist values at 12- than at 6-month follow-ups; Stepped Care and BWL (Standard) groups did not differ significantly (F(1,152)=0.77, p=0.38) nor was there a significant treatment-by-time interaction (F(1,139)=1.28, p=0.26). Within Stepped Care, post-treatment and follow-up scores were significantly associated (F(1,112)=514.93, p<.0001) and there was a significant medication-by-time interaction (F(1,103)=4.08, p=0.05) although medication and placebo conditions did not differ significantly at either 6- or 12-months (F(1,111)=0.12, p=0.73 and F(1,116)=1.25, p=0.26) nor was the time effect significant (F(1,103)=1.24, p=0.27). Analysis of the four treatments within Stepped Care revealed they did not differ significantly (F(3,111)=0.28, p=0.84) nor was there a significant treatment by time interaction (F(3,101)=2.31, p=0.08).

Discussion

This study examined the longer-term outcomes of BWL and an adaptive “SMART” Stepped-care approach integrating weight-loss medications for patients with BED with co-existing obesity. This study focused on findings through 12-month follow-up after completing 6-month acute treatments (i.e., 18 months after randomization) described previously (15). At 12-month follow-up, the two treatment approaches had remission rates of 41% (BWL) and 45% (Stepped Care). During the 12-month follow-up, the amount of weight regain did not differ significantly between BWL and Stepped Care (+1.3% and +1.7%, respectively, from posttreatment weight values); importantly, total percent weight loss from baseline 18-months earlier was −3.4% (BWL) and −5.0% (Stepped Care). Paralleling the improvements in the primary outcomes (binge-eating and weight losses) were the improvements in secondary outcomes (eating-disorder psychopathology, depression, and waist circumference) observed at 12-month follow-ups which did not differ significantly from posttreatment values. The 12-month follow-up results in binge-eating and in the associated (secondary) outcomes are consistent with those previously reported for BWL (9) and generally comparable to those for “specialist” therapies such as CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy (9,37).

Total percent weight loss from baseline 18 months earlier was −3.4% (BWL) and −5.0% (Stepped Care). The degree of maintained weight-losses is noteworthy for several reasons. Achieving weight loss, let alone maintaining it, in this subgroup of persons with obesity who also have BED has been challenging (13). The weight-loss outcomes for BWL and for Stepped Care exceeded those previously reported by Grilo and colleagues (9) for both BWL and CBT and comparable to those reported by Wilson and colleagues (37) for BWL but clearly exceed those for CBT and IPT. These weight losses, however, were dampened relative to those reported by Wadden and colleagues (34) in their treatment study of BWL and sibutramine, alone and in combination, for patients with obesity without co-existing BED. In contrast to these findings for the weight-loss medication sibutramine used in combination with a very similar BWL treatment in the present study and in the Wadden et al (34), Grilo and colleagues (24) reported similar weight losses during acute treatment with sibutramine (without BWL) for BED but that substantial weight regain occurred following treatment once the medication was discontinued. These findings suggest the importance of an intensive behavioral treatment “platform” to enhance longer-term benefits of weight-loss medication.

Collectively, the outcomes, achieved with BWL and in Stepped Care utilizing BWL and weight-loss medications, represent a strong counter-argument against longstanding controversial claims that BWL is not only ineffective for weight loss but might exacerbate binge eating or associated eating-disorder pathology in individuals with obesity (e.g., 40). While early models of binge eating theorized that restrictive dieting might trigger or worsen binge eating (41), it is important to emphasize and clarify that BWL should not be viewed incorrectly as a rigid restrictive “diet” but rather as a balanced moderate lifestyle approach to eating and physical activity delivered with a behavioral therapy platform built upon sustainable goals and facilitated via enhanced coping skills. Our findings converge with other recent controlled intensive treatment studies that BED is not a contraindication for BWL (9,37) and that those patients with obesity who binge eat can benefit from BWL, although persistent/higher binge eating attenuates weight loss (42).

Future research needs to identify methods to enhance maintenance and longer-term outcomes. At 12-month follow-ups, the abstinence rates for BWL (41%) and Stepped Care (45%) indicate that roughly one-third who achieved binge-eating remission during treatment were no longer completely free from binge eating. Research is needed to identify patient predictors of vulnerability to relapse as well as triggers for lapses as such data could inform targeted treatment efforts. Research should also investigate the utility of “booster” follow-up interventions.

Future research also needs to find methods to facilitate greater weight losses in patients with BED with co-existing obesity. There were few weight-loss pharmacotherapy options when this treatment study was designed; thus, we selected sibutramine (subsequently withdrawn) and orlistat (minimal effects on binge eating and weight). Nonetheless, the findings still have heuristic value and are informative for planning adaptive SMART designs that might have greater effectiveness. Several weight-loss medications are now available that appear more relevant given their putative mechanisms of action, such as naltrexone/bupropion combination (43). There also now exists a FDA-approved medication for BED (lisdexamfetamine) (11) and research is underway evaluating it in combination with CBT. Emerging research supports the effectiveness of new agents for BED, such as dasotraline (44), that may warrant further research using traditional and adaptive treatment designs. Generalizability of findings to different settings and generalist practitioners is uncertain (24) and may differ from treatments naturalistically sought by patients (7) as they likely differ from the interventions and how they were delivered in this study.

Study Importance Questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Most evidence-based treatments for binge-eating disorder do not produce weight loss among individuals with co-existing obesity.

Maintaining weight loss is a major challenge for obesity treatments.

Maintaining changes in weight after treatment is challenging but little is known about maintaining changes in binge eating following behavioral weight loss and medication treatments.

What are the new findings in your manuscript?

41%–45% of patients receiving behavioral weight loss and Stepped Care remained abstinent from binge eating 12 months after completing these treatments.

Total percent weight loss from baseline 18 months earlier was −3.4% and −5.0% for patients receiving behavioral weight loss and Stepped Care.

Binge-eating and weight-loss outcomes attained with behavioral weight loss treatments with and without weight-loss medications did not differ significantly at 12-month follow-ups after completing treatments and discontinuing medications.

How might your results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

Future research should examine further adaptive SMART designs with behavioral treatment and newer medications developed for weight loss and binge-eating disorder.

Future research should investigate patient predictors of vulnerability to relapse and ways to enhance longer-term maintenance.

Behavioral weight loss should be considered an evidence-based treatment for co-existing binge-eating disorder and obesity.

Funding:

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK49587 (Dr. Grilo). Funding agency played no role in the content of this paper.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Dr. Grilo reports broader interests, which did not influence this research, including: Consultant to Sunovion and Weight Watchers; Honoraria for lectures, CME activities, and lectures at scientific conferences, and Royalties from Guilford Press and Taylor & Francis Publishers for academic books.

Data Sharing: De-identified data will be provided in response to reasonable written request to achieve goals in an approved written proposal.

Clinicaltrials.gov registration number: NCT00829283 (Treatment of Obesity and Binge Eating: Behavioral Weight Loss Versus Stepped Care)

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Udo T, Grilo CM. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5-defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Biol Psychiatry 2018;84:345–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Udo T, Bitley S, Grilo CM. Suicide attempts in US adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders. BMC Medicine 2019;17:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Udo T, Grilo CM. Psychiatric and medical correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States. Int J Eat Disord 2019;52:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balodis IM, Molina ND, Kober H, et al. Divergent neural substrates of inhibitory control in binge eating disorder relative to other manifestations of obesity. Obesity 2013;21:367–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, White MA. Significance of overvaluation of shape/weight in binge-eating disorder: comparative study with overweight and bulimia nervosa. Obesity 2010;18:499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffino JA, Udo T, Grilo CM. Rates of help-seeking in U.S. adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders: Prevalence across diagnoses and sex and ethnic/racial differences. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2019;94:1415–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grilo CM. Psychological and behavioral treatments for binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2018;78(S1): 20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, White MA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychology 2011;79:675–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McElroy SL. Pharmacologic treatments for binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2017;78(S1):14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McElroy SL, Hudson J, Ferreira-Cornwell M, Radewonuk J, Whitaker T, Gasior M. Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate for adults with moderate to severe binge-eating disorder: Results of two pivotal phase 3 randomized controlled trials. Neuropsychopharmacol 2016;41:1251–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilbert A, Petroff D, Herpertz S, Pietrowsky R, Tuschen-Caffier B, Vocks S, Schmidt R. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of psychological and medical treatments for binge-eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2019;87:91–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blaine B, Rodman J. Responses to weight loss treatment among obese individuals with and without BED: matched-study meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord 2007;12:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grilo CM, Reas DL, Mitchell JE. Combining pharmacological and psychological treatments for binge eating disorder: current status, limitations, and future directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016:18:55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM, Ivezaj V, Morgan PT, Gueorguieva R. Randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of adaptive “SMART” stepped-care treatment for adults with binge-eating disorder comorbid with obesity. Am Psychol 2020:75:204–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almirall D, Nahum-Shani I, Sherwood NE, Murphy SA. Introduction to SMART designs for the development of adaptive interventions: with application to weight loss research. Trans Beh Med 2014;4:260–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nahum-Shani I, Qian M, Almirall D, Pelham WE, Gnagy B, Fabiano GA, Waxmonsky JG, Yu J. Experimental design and primary data analysis methods for comparing adaptive interventions. Psychol Meth 2012;17:457–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Rapid response to treatment for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:602–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM, Ivezaj V, Morgan PT, Gueorguieva R. Predicting meaningful outcomes to medication and self-help treatments for binge-eating disorder in primary care: The significance of early rapid response. J Consult Clin Psychol 2020;83:387–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linardon J, Brennan L, de la Piedad Garcia X. Rapid response to eating disorder treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 2016;49:905–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grilo CM, White MA, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, Masheb RM. Rapid response predicts 12-month post-treatment outcomes in binge eating disorder: theoretical and clinical implications. Psychol Med 2012;42:807–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Rapid response predicts treatment outcomes in binge-eating disorder: implications for stepped care. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75:39–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Wilson GT, Masheb RM. 12-month follow-up of fluoxetine and cognitive behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:1108–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grilo CM, Masheb R, White MA, Gueorguieva R, Barnes R, Walsh BT, McKenzie K, Genao I, Garcia R. Treatment of binge eating disorder in racially and ethnically diverse obese patients in primary care: randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of self-help and medication. Behav Res Ther 2014;58:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders-patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Ver 2.0) NY: NYSPI, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O’Connor M. (2008). The Eating Disorder Examination (16.0D) In Fairburn CG. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. NY: Guilford Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: a replication. Obesity Res 2001;9:418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2004;35:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck AT, Steer R. Manual for revised Beck Depression Inventory. New York: Psychological Corporation, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck AT, Steer R, Garbin M. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: 25 years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1998;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 31.NHLBI. Practical guide: identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. NIH Publication Number 00–4084, 2000.

- 32.Pouliot MC, Despres JP, Lemieux S, Moorjani S, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Nadeau A, Lupien PJ. Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Cardiol 1994;73:460–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brownell KD. LEARN program for weight management. Dallas: Am Health Pub., 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Phelan S, Cato RK, Hesson LA, Osei SY, Kaplan R, Stunkard AJ. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2111–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther 2005;43:1509–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Salant SL. Cognitive behavioral therapy guided self-help and orlistat for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57:1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Bryson SW. Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:94–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Hudson JI, Mitchell JE, Berkowitz RI, Blakesley V, Walsh BT, Sibutramine Binge Eating Disorder Research Group. Efficacy of sibutramine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: A randomized multi-center placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davidson MH, Hauptman J, DiGirolamo M, et al. Weight control and risk factor reduction in obese subjects treated for 2 years with orlistat: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 1999;281:235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wooley SC, Garner DM. Obesity treatment: the high cost of false hope. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991;91:1248–1251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polivy J, Herman CP. Dieting and binging: a causal analysis. Am Psychol. 1985;40:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chao AM, Wadden TA, Gorin AA, Troieri JS, Pearl RL, Bakizada ZM, Yanovski SZ, Berkowitz RI. Binge eating and weight loss outcomes in individuals with type II diabetes: 4-year results from the Look AHEAD Study. Obesity. 2017;25:1830–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, Mudaliar S, Guttadauria M, Erickson J, Kim DD, Dunayevich E. COR-I Study Group. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multi-centre randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010;376:595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grilo CM, McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Tsai J, Navia B, Goldman R, Deng L, Kent J, Loebel A. Efficacy and safety of dasotraline in adults with binge-eating disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial. CNS Spectrums 2020; in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]