Abstract

Exposure to genotoxic stress by environmental agents or treatments, such as radiation therapy, can diminish healthspan and accelerate aging. We have developed a Drosophila melanogaster model to study the molecular effects of radiation-induced damage and repair. Utilizing a quantitative intestinal permeability assay, we performed an unbiased GWAS screen (using 156 strains from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel) to search for natural genetic variants that regulate radiation-induced gut permeability in adult D. melanogaster. From this screen, we identified an RNA binding protein, Musashi (msi), as one of the possible genes associated with changes in intestinal permeability upon radiation. The overexpression of msi promoted intestinal stem cell proliferation, which increased survival after irradiation and rescued radiation-induced intestinal permeability. In summary, we have established D. melanogaster as an expedient model system to study the effects of radiation-induced damage to the intestine in adults and have identified msi as a potential therapeutic target.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Physiology, Stem cells

Introduction

A typical mammalian cell encounters approximately 2 × 105 DNA lesions per day1. External stressors, both chemical and radioactive, and internal factors such as oxidative stress, are the primary sources of DNA damage2. The inability to correct DNA damage results in the accumulation of harmful mutations, which contribute to cellular damage, cancer, and aging3–8. However, DNA damaging agents, such as radiation, are the only available treatments for certain pathologies. These therapies can lead to complications due to cellular and tissue damage caused by genotoxic stress. For example, genetic and epigenetic alterations in the tumor9, or tumor microenvironment, may render it resistant to radiation10. Additionally, bystander tissues are also damaged from radiotherapy11,12. Patients undergoing radiotherapy encounter both short-term side effects (nausea, vomiting, and damage to epithelial surfaces) and long-term side effects like enteritis13, radiation proctitis, heart disease14, and cognitive decline15.

Multiple organisms have developed several DNA error correction mechanisms, as the inability to correct DNA errors leads to permanent cellular damage16–19. Cells undergo one of the following fates: apoptosis, replicative arrest, such as senescence, or clearance by phagocytosis or autophagy20. These fates often involve the cell non-autonomous interactions, which cannot be recapitulated by in vitro models of genotoxic stress. Furthermore, they fail to represent the complexities of tissue microenvironments and the cell non-autonomous consequences of radiation damage. For instance, apoptotic or senescent cells may produce secreted factors that exacerbate damage to cells that did not receive the primary insult21.

As the gastrointestinal tract encompasses a large area in the body and has the highest turnover rate22,23, it is commonly a bystander tissue in radiotherapy accounting for significant side effects of radiation treatment24,25. The fly and human intestines share similar tissue, anatomy, and physiological function26,27; both fly and mammalian guts are composed of intestinal stem cells (ISCs), enterocytes (ECs), and enteroendocrine (EE) cells28. ISCs are involved in regenerative and tissue-repair processes29,30 in flies and mammals31. DNA damage to the ISCs leads to a reduced proliferative potential, which contributes to the pathogenesis of radiation enteritis in patients undergoing radiation therapy32–35. Previous studies have used the flies to study radiation damage, but these studies have been restricted to studying its impact during development36,37. Studies involving D. melanogaster have revealed conserved molecular pathways that maintain stem cell function, tissue repair, and homeostasis in the intestine38–40. Here, we have taken advantage of the flies’ genetic malleability, short lifespan, and complex tissue microenvironments to develop a whole-animal model to study therapeutic targets for radiation damage to the intestine.

Results

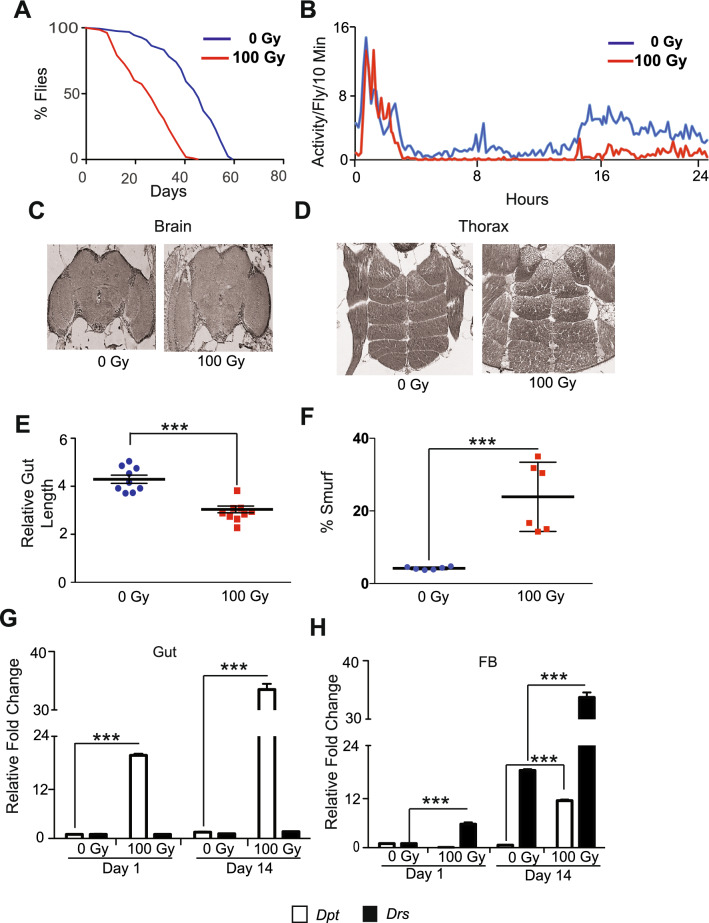

Ionizing radiation reduces survival and locomotion in D. melanogaster

Even though ionizing radiation (IR) is extensively studied in the context of mutagenesis experiments41,42 and embryonic development signals43 in D. melanogaster, not much is known regarding its effects in adult flies. We exposed 5-day old w1118 adult flies to different doses of IR. Interestingly, these flies were fairly resistant to lower doses of X-rays (from 1 to 10 Gy), likely because most tissues in the fly are post-mitotic44. However, when we exposed female w1118 flies to 100 Gy, it significantly reduced their mean lifespan, compared to un-irradiated controls (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. 1A). We observed a similar reduction in lifespan in irradiated male flies, indicating that adult sensitivity to IR is sex independent (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Radiation-induced damage in the gut results in a significant reduction in survival and spontaneous activity of Drosophila. (A) Kaplan Meier survival analysis upon irradiation of 5 day old flies. Non-irradiated control (0 Gy) and irradiated group (100 Gy), respectively. (B) The effect of radiation on spontaneous activity. The graph shows averaged activity per 10 min for control (0 Gy) and irradiated flies (100 Gy). The X-axis represents time (in hours) after the flies were moved to the activity monitors. The activity measurement was started at 4:00 p.m. (C) Representative H and E (Hematoxylin and eosin) staining of the paraffin-embedded brain and (D) thorax of w1118, 7 days after irradiation showing no structural abnormalities. (E) The graph represents intestine length measured using ImageJ. The relative length of the w1118 5 days old adult female flies 14 days after irradiating with or without 100 Gy is plotted as arbitrary units. Each dot represents one sample. (***p < 0.001 by t-test). (F) The effect of radiation on gut permeability. Smurf assay to access gut permeability was performed in w1118 adult female flies 14 days after irradiating with or without 100 Gy. Results were plotted as mean percentage of ‘Smurf’ to non-smurf flies. Error bars indicate S.D. of 6 replicates. (***p < 0.001 by t-test). (G) Relative fold change in the expression of Diptericin (Dpt) and Drosomycin (Drs) in the gut and (H) fat body (FB). The results are represented as mean relative fold change in the gene expression and normalized to housekeeping gene rp49 on days 1 and 14 after irradiation (100 Gy), demonstrating local and systemic inflammation. (***p < 0.001 by t-test).

A frequent adverse effect of radiation exposure is fatigue45–50. Several groups have observed that irradiated mice have diminished spontaneous and voluntary activity51,52. We used the Drosophila Activity Monitor System to examine whether radiation also reduces flies' spontaneous physical activity53. Our results showed that irradiated flies display a reduction in spontaneous physical activity 14 days after IR exposure (Fig. 1B). To determine if this was due to damage to the brain and/or the muscles, we evaluated the morphological changes in the brain as well as flight and thoracic muscles in irradiated flies by hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining. We did not observe any overt structural damage to the brain (Fig. 1C). Also, we did not observe significant structural damage to the muscles in the thorax, day one (not shown), and seven after irradiation (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that neither muscle nor brain damage accounts for the reduction in survival and activity in irradiated flies.

Ionizing radiation disrupts intestinal integrity and induces inflammation

Intestinal barrier disruption in flies is known to impact survival54. Thus, we examined whether the reduced survival of irradiated flies was due to damage to intestinal tissue. Our results showed that irradiated flies have significantly shorter intestines than non-irradiated controls 14 days after irradiation, which suggests that irradiation structurally damages the fly's intestine (Fig. 1E and Supplementary Fig. 1C). We hypothesized that this structural damage to the intestine influence barrier function. To test this, we measured the effect of irradiation on intestinal permeability by performing the previously described Smurf assay55, which involves feeding a blue dye. Our results in Fig. 1F demonstrate a significantly higher percentage of flies with permeable intestine (Smurf flies) upon irradiation when compared to un-irradiated controls 14 days after irradiation. We observed that this effect of ionizing radiation on intestinal permeability was responsive to increasing doses of radiation (Supplementary Fig. 1D). Furthermore, the cumulative effect of radiation on intestinal permeability when the dosage was staggered (4 doses of 25 Gy every other day) was similar in extent to the flies exposed to a single dose of 100 Gy, when intestinal permeability was measured by Smurf assay performed 14 days after irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 1E). The effect of exposure to ionizing radiation on intestinal permeability was sex independent, as Smurf assay revealed twofolds higher proportion of flies with permeable intestines in both males and females (Supplementary Fig. 1F). Finally, we also observed an increase in intestinal permeability in wild-type flies, Canton-S, due to damage caused by radiation (Supplementary Fig. 1G).

The disruption of gut barrier integrity after irradiation has been shown to result in increased local and systemic immune activation, indicated by the secretion of anti-microbial peptides (AMPs)55. To test this, we investigated the effect of radiation on the expression of the AMPs, Diptericin (Dpt) and Drosomycin (Drs), in dissected guts and fat bodies, which served as a proxy for systemic (fat bodies) and local (intestines) inflammation56,57. Quantitative realtime PCR (qRT-PCR) of RNA isolated from dissected intestinal tissue samples indicated a 20-fold increase in Dpt expression as early as 24 h after irradiation, which increased to 30-fold after 14 days of irradiation. This increase coincided with the intestinal permeability observed in our Smurf analysis (Fig. 1G), which also indicates elevated Immune Deficiency (IMD) signaling, a critical response to bacterial infection58 in the intestine of irradiated flies.

Fat body in Drosophila contributes to the humoral immune response. Hence its AMP production serves an indicator for systemic inflammation59,60. The qRT-PCR with the samples from the fat body revealed a fourfold increase in the expression of Drs after day 1, and a 35-fold increase 14 days after irradiation (Fig. 1H). This indicates a sustained increase in systemic inflammation from elevated Toll signaling61 in the fat body of irradiated flies. In the fat body we also saw an increase in the expression of Dpt by 14 days after irradiation. Together, these results demonstrate that irradiation induces a sustained local and systemic inflammatory response in the adult flies.

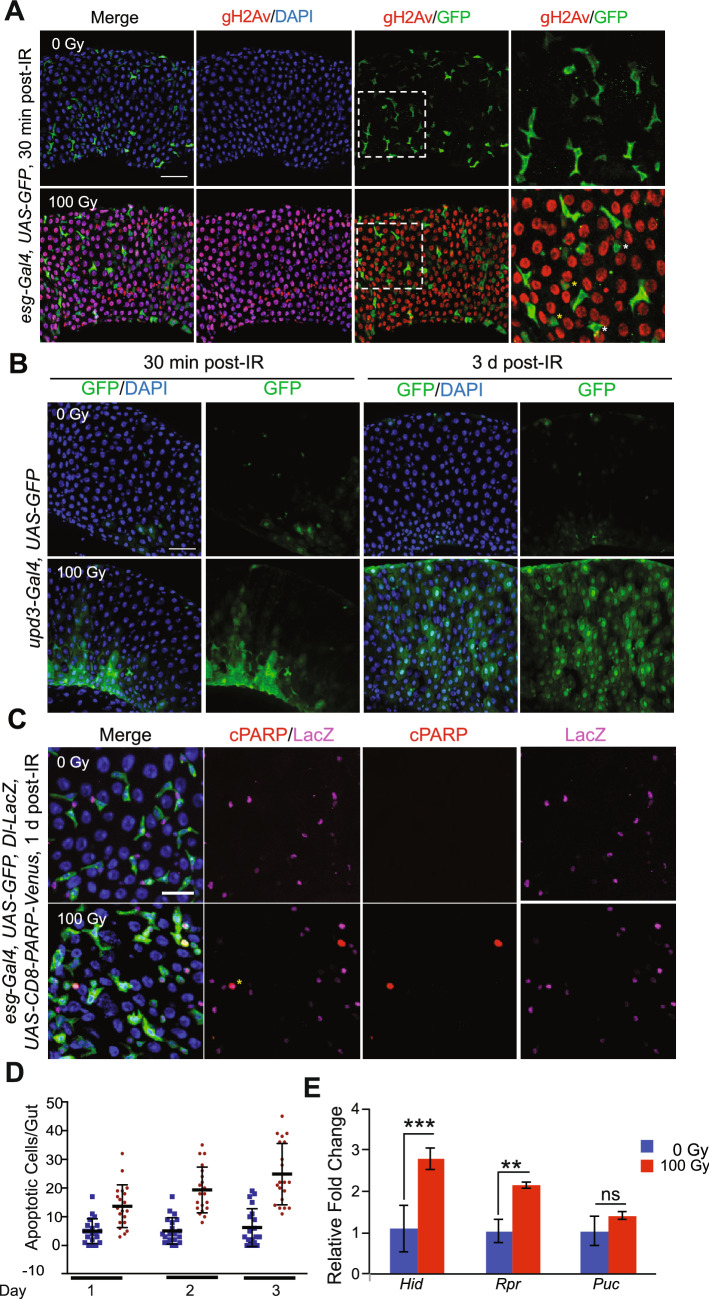

Exposure to radiation caused DNA damage, cell death in enterocytes and inhibited ISC proliferation

Exposure to ionizing radiation induces DNA double-strand breaks (DSB)62,63. One of the earliest events following DSBs is activation of kinases like ATM, ATR and DNA-PK, which phosphorylate the C-terminal tail of the histone 2A64. This DSB-induced phosphorylation of histone 2A (H2A) is conserved in Drosophila65,66. We tested the effect of ionizing radiation on histone γ-H2Av, the fly orthologue of H2AX, phosphorylation in flies' intestinal tissue by immunofluorescence staining. To visualize ISCs and its daughter cells, enteroblasts (EBs), we used esg-Gal4 line to drive UAS-GFP transgene (referred to as esg-GFP)28. Following irradiation, cells in the intestine of the flies showed a substantial increase in γ-H2Xv foci compared to cells in the intestine of non-irradiated flies (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 2A). Although most of esg-GFP positive cells did not show γ-H2Xv foci, approximately 7% of these cells showed DNA damage (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 2A′). Environmental stress on gut enterocytes is known to activate reparative responses, often initiated by the IL-6-like cytokine, Upd367. We tested if persistent DNA damage, caused by radiation, affects Upd3 expression at 30 min and 3 days after irradiation. Our results indicated that the nuclear-localized Upd3 expressing cells were significantly increased 3 days after irradiation, based on GFP reporter expression (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Exposure to radiation causes DNA damage and cell death in enterocytes and inhibition of ISC proliferation. (A) Midguts were stained with anti-γ-H2Av antibody and DAPI. Guts from esg-Gal4, UAS-GFP flies were dissected 30 min after irradiation with (bottom panels) or without (top panels) 100 Gy. Right panels are magnified images of the white square in the left side panels. Yellow asterisks indicate the both γ-H2Av and GFP positive cells. White asterisks indicate the γ-H2Av negative GFP positive cells. Scale bar indicates 40 µm. (B) Midguts were stained with anti-GFP antibody and DAPI. Guts from upd3-Gal4, UAS-GFP flies were dissected 30 min and 3 days after irradiation with (bottom panels) or without (top panels) 100 Gy. Scale bar indicates 40 µm. (C) Midguts were stained with anti-cPARP antibody, anti-LacZ antibody and DAPI. Guts from esg-Gal4, UAS-GFP, Dl-LacZ, UAS-CD8-PARP-Venus flies were dissected 1 day after irradiation with (bottom panels) or without (top panels) 100 Gy. Yellow asterisk indicates the both cPARP and LacZ positive cell. Scale bar indicates 20 µm. (D) Ethidium bromide-Acridine Orange staining was performed in guts of w1118 female flies after irradiation (100 Gy) at indicated time points. The results are plotted as the mean number of apoptotic cells per gut and presented and mean apoptotic cells and error bars indicate S.D. of 2 independent experiments with at least 10 guts each. (E) Relative fold change in the expression of Hid, Rpr and Puc in the dissected gut 24 h after irradiation. The error bars indicate S.D. of 4 replicates. (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, nsp > 0.05 by t-test).

Metazoan cells also undergo apoptosis following DNA DSB. Thus, we investigated the effect of radiation on apoptosis in the fly's intestine. We overexpressed UAS-CD8-PARP-Venus, a probe for the caspase activation68,69 in both ISCs and EBs using esg-Gal4 with Delta-LacZ background, and apoptotic cells were detected by immunostaining with the anti-cleaved PARP antibody. We found that Delta-LacZ marked ISCs underwent apoptosis 1 day after irradiation (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. 2C). These results suggested that increased gut permeability after irradiation is due to loss of regenerative capacity caused by the death of ISCs. SYTOX staining for apoptotic cells performed in these flies demonstrated esg-negative cells (EC, EE) are also becoming SYTOX positive after irradiation and undergoing apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 2D and 2D′). We also performed Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide staining assay in dissected intestinal tissue, which showed a nearly two-fold increase in the number of apoptotic cells on days 1, 2 or 3 following irradiation70 (Fig. 2D). These results were also supported by increased expression of the pro-apoptotic genes, hid and reaper71 24 h after irradiation as measured by qRT-PCR of RNA isolated from dissected intestine (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, we did not see an increase in the expression of puckered72, a marker of JNK induced apoptosis in the intestines of irradiated flies.

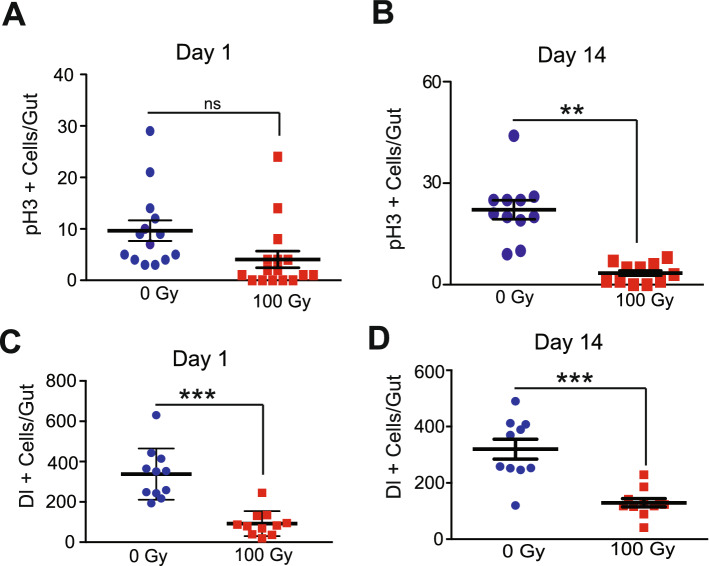

Exposure to X-rays inhibited ISC proliferation and increased intestinal permeability

Previous studies have shown that fly guts respond to damage from toxins like dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) or Bleomycin73, and stress from a bacterial infection74 by inducing the proliferation of ISCs which enhances intestinal repair by replacing damaged cells75. We investigated whether ISCs in irradiated flies could mediate tissue homeostasis by replacing apoptotic enterocytes by immunostaining guts with an anti-phospho-Histone H3 (anti-pH3) antibody that marks dividing cells. Immunofluorescence staining in dissected guts demonstrated that irradiation inhibited ISC proliferation as early as 1 day after irradiation (Fig. 3A). This inability of ISCs to repair damage was more clearly observed 14 days after irradiation (Fig. 3B). We also irradiated a fly strain harboring a Delta-LacZ enhancer trap that has been extensively used to identify ISCs76,77. We observed that exposure to radiation significantly reduced the number of Delta positive ISCs and ISC markers (1 and 14 days after irradiation) (Fig. 3C,D), consistent with our observation that Delta positive ISCs underwent apoptosis (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. 2C).

Figure 3.

Radiation-induced damage inhibits the proliferation of intestinal stem cell. (A) ISC proliferation was measured by counting the numbers of pH3-positive cells detected in w1118 flies irradiated with 100 Gy day 1 and (B) day 14. The result is presented as mean ± SE of at least 10 guts per group. (**p < 0.01, nsp > 0.05 by t-test). (C) The effect of irradiation on the ISC number was tested by counting the numbers of Dl-LacZ positive cells. ISC numbers were determined by immunostaining with anti-β-Gal antibody in dissected guts of Dl-LacZ flies on days 1 and (D) day 14 after irradiation. The result is presented as mean ± SE of at least 10 guts per group. (***p < 0.001 by t-test in each group). Error bars indicate SEM (***p < 0.001 by t-test).

Fly Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) for radiation-induced intestinal permeability

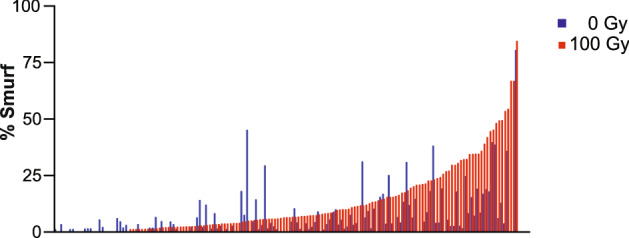

Genetic variations influence sensitivity to genotoxic stress, the detrimental effects of radiation treatment, and the prognosis of radiation therapy78–87. We leveraged the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP) that contains flies with fully sequenced genetic variations, to conduct an unbiased GWAS screening of approximately 156 fly strains from the DGRP. Approximately 100 flies from each strain were irradiated with 100 Gy, and the percentage of Smurf flies was measured 14 days after irradiation. The genetic markers with > 25% minor allele frequency were used for screening88. The lines were split into two groups, one for each allele at a given genetic locus. Linear regression modeling was used to determine the difference between phenotypes associated with each allele. The FDR for each trait was calculated by permutation of the phenotypic data89.

The DGRP lines varied in radiation-induced gut permeability, from a 14-fold increase in Smurf incidence to a 20-fold decrease in Smurf incidence (Fig. 4). Our GWAS analysis revealed several potential candidate genes (Table 1). However, we set a cutoff of false detection rate (FDR) of 27% or less to consider the genes for further validation88. We investigated the candidates listed in Table 1 for their ISC-specific influence on intestinal permeability after irradiation. To test this, we crossed fly lines expressing an RNAi against the candidate genes (like msi, Ddr, and cka) with lines expressing the drug (RU486)-inducible ISC-specific 5961-Gene Switch-Gal4 (5961-GS) driver and measured intestinal permeability 14 days after irradiation. We observed the most significant increase in gut permeability in 5961-GS > msi RNAi(musashi) flies after irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Phenotypic variation in gut permeability across 156 DGRP lines caused by radiation exposure. Lines are arranged in order of increasing phenotype of the irradiated lines, paired with their non-irradiated controls. Gut permeability was determined by Smurf assay and results were plotted as mean proportion of ‘Smurf’ to non-smurf flies in each group with at least 100 flies were tested per condition.

Table 1.

List of candidate genes identified by GWAS analysis of Smurf data collected from DGRP fly lines.

| Cka marker | Gene | Human orthologue | Effect/location | Interaction P value |

FDR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2L_6284412_SNP | Ddr | DDR2 | INTRON | 0.00030849 | 0 |

| 2L_6283921_SNP | Ddr | DDR2 | INTRON | 0.00070189 | 8 |

| 3L_3480865_SNP | CG42324 | TJAP1 | INTRON | 0.00109696 | 10 |

| 3R_21373234_SNP | msi | MSI1/2 | INTRON | 0.00140678 | 14 |

| X_12489073_SNP | CG1824 | ABCB8 | NON _CODING | 0.00206947 | 24 |

| 2L_8035397_SNP | Cka | STRN3 | INTRON | 0.00217694 | 25 |

The table is showing the location of the SNP associated with increased intestinal permeability, and location of the SNP. The candidates with False discovery rate ≤ 25% for analysis.

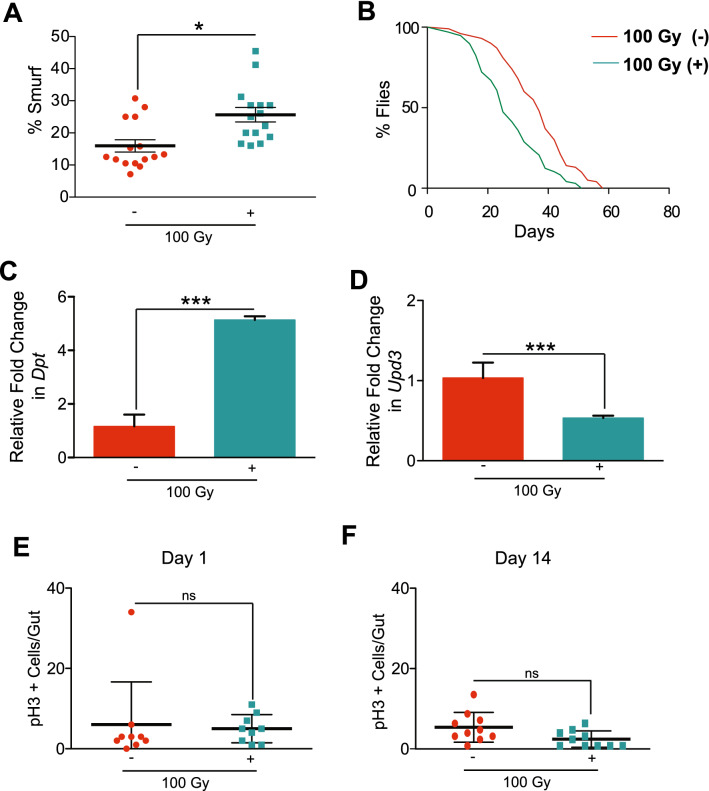

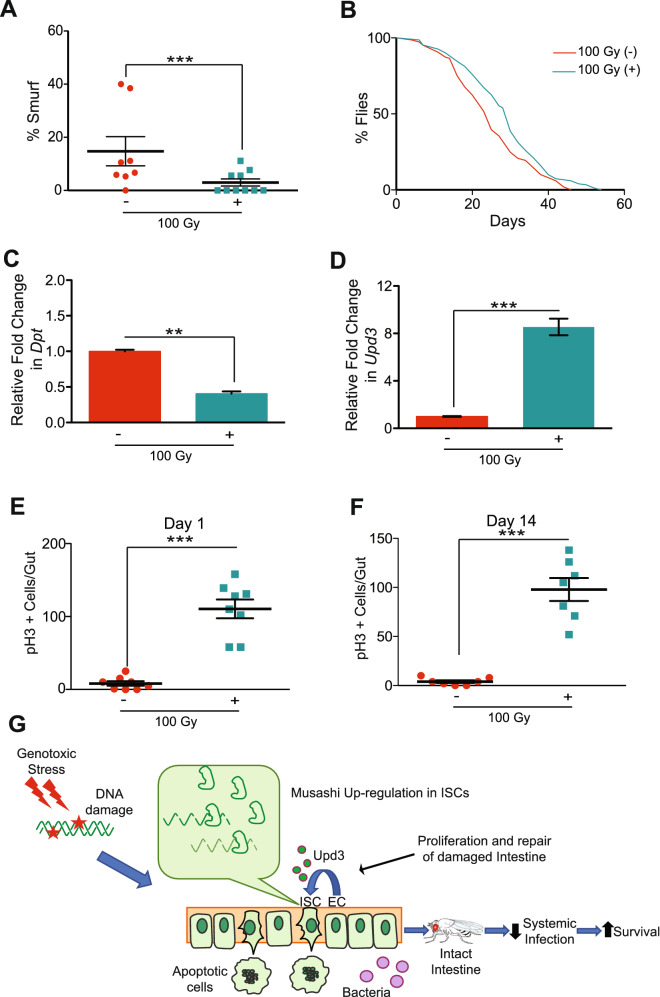

msi regulated ISC function, intestinal permeability, and survival in response to radiation-induced damage

Msi belongs to a family of highly conserved RNA-binding translational repressors that are expressed in proliferative progenitor cells90–92. To test its role in ISC proliferation upon DNA damage, we used the (RU486)-inducible ISC-specific 5961-GS driver in 14-day-old adult flies to knockdown msi expression93. Knocking down msi in ISCs (+), followed by irradiation, enhanced the defect in gut permeability by almost two-fold compared to irradiated control flies (without RU486) (−) exposed to 100 Gy (Fig. 5A). We also found that msi RNAi in ISCs further reduced survival upon irradiation (Fig. 5B). To further characterize the impact of msi on radiation sensitivity, we tested whether msi expression in ISC’s affected immune activation. Upon irradiation msi RNAi flies showed a significant upregulation in Dpt in the gut (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the qRT-PCR result in the same dissected guts indicated a reduced expression of Upd3 upon msi knockdown (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Reducing msi expression in ISCs increases gut permeability and reduces survival by inhibiting stem cell proliferation. (A) Smurf assay for assessing gut permeability was performed with 5961-GS > UAS-msi RNAi flies on day 14 after irradiation. Control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi was reduced in ISCs in 100 Gy (+). The error bars indicate S.D. of percent Smurf flies per vials. (*p < 0.05 by t-test). (B) Kaplan Meier survival analysis of 5961-GS > UAS-msi RNAi flies was performed after 100 Gy irradiation. At least 150 flies were used each group with control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi expression was knocked down in ISCs in 100 Gy (+). (C) Relative fold change in the expression of Diptericin (Dpt) in the dissected gut, 14 days after irradiation. Control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi was knocked down in ISCs in 100 Gy (+). The error bars indicate S.D. of 4 replicates. (***p < 0.001 by t-test). (D) Relative fold change in the expression of Unpaired3 (Upd3) in the gut, 24 h after irradiation. The error bars indicate S.D. of 4 replicates. (***p < 0.001 by t-test). Control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi was knocked down in 100 Gy (+). (E) The number of pH3-positive cells detected per gut of 5961-GS > UAS-msi RNAi flies, on day 1 and (F) day 14 after irradiation. Control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi was knocked down in ISCs in 100 Gy (+). The result is represented as mean ± SE of at least 10 guts per group. (ns p > 0.05 by t-test) of 3 independent experiments.

Because msi is known to regulate cell fate and stemness94, and irradiation significantly reduces ISC proliferation, we investigated the effect of knocking down msi on ISC proliferation in response to radiation. We observed that the ISC proliferation upon knockdown of msi in ISCs was relatively lower and comparable to the control flies as measured by immunofluorescence for phospho-Histone 3 (pH3) in dissected guts 1 day and 14 days after irradiation (Fig. 5E,F). ISC-specific msi knockdown also reduced ISC proliferation in the un-irradiated control flies, suggesting that msi is required for ISC proliferation in general (Supplementary Fig. 4A).

Consistent with the knockdown analysis, overexpression of msi in ISCs (+) in irradiated flies resulted in a significant reduction in gut permeability compared to irradiated control flies (without RU486) (−) (Fig. 6A). Accordingly, msi overexpression resulted in a marginal but significant increase in survival and also showed a significant reduction in Dpt expression (Fig. 6B,C). However, msi overexpression in enterocytes (EC) using 5966-GS driver did not rescue the gut permeability phenotype in irradiated flies (not shown), which supports an ISC-specific function for msi. Interestingly, ISC-specific msi overexpression significantly increased Upd3 expression in the gut 24 h after irradiation (Fig. 6D), as seen by qRT-PCR in dissected intestines. Furthermore, pH3 immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that msi overexpression significantly increased ISC proliferation almost 15-fold after irradiation, although overexpression of msi in the un-irradiated control flies did not affect ISC proliferation (Fig. 6E,F, and Supplementary Fig. 4B). These results suggest that msi overexpression in ISCs re-boosts the regeneration capacity of the intestine after irradiation. Thus, the improved survival of flies upon overexpressing msi was, in part, correlated with its ability to increase ISC proliferation. As expected, RU486 on its own did not have any effect on the ISC proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 4C). Next we examined if enhancing ISC proliferation can protect against radiation induced damage. The Cyclin E/CDK2 plays a critical role in the G1 phase and the G1-S phase transition95, and when overexpressed, it overcomes cell cycle arrest96. We overexpressed Cyclin E (CycE) in ISCs (with 5961-GS) to test whether forced ISC proliferation rescued intestinal damage after irradiation. Flies where CycE was overexpressed (+), in an ISC-specific manner, had significantly increased ISC proliferation (as measured by pH3 staining in the intestine) when compared to the irradiated control without the RU486 (−) (Supplementary Fig. 5A). However, the overexpression of CycE in ISCs had no effect on ISC proliferation in un-irradiated flies (Supplementary Fig. 5B). We then determined whether CycE over-expression in ISCs of irradiated flies also reduced intestinal permeability. We performed the Smurf assay in these flies and found a two-fold reduction in the percentage of flies with permeable guts, compared to the irradiated control (Supplementary Fig. 5C). Thus, overexpression of either msi or CycE, increases ISC proliferation and protects against radiation-induced intestinal permeability.

Figure 6.

Increasing msi expression in ISCs reduces gut permeability and increases survival by restoring stem cell proliferation. (A) Smurf assay for assessing gut permeability was performed with 5961-GS > UAS-msi flies on day 14 after irradiation. Control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi was overexpressed in ISCs in 100 Gy (+). The error bars indicate S.D. of percent Smurf flies per vials. (***p < 0.001 by t-test). (B) Kaplan Meier survival analysis of 5961-GS > UAS-msi flies was performed after 100 Gy irradiation. At least 150 flies were used each group with control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi was overexpressed in ISCs in 100 Gy (+). (C) Relative fold change in the expression of Diptericin (Dpt) in the dissected gut, 14 days after irradiation. Control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi was overexpressed in ISCs in 100 Gy (+). The error bars indicate S.D. of 4 replicates. (**p < 0.01 by t-test). (D) Relative fold change in the expression of Unpaired3 (Upd3) in the gut, 24 h after irradiation. The error bars indicate S.D. of 4 replicates. (***p < 0.001 by t-test). Control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi was overexpressed in 100 Gy (+). (E) The number of pH3-positive cells detected per gut of 5961-GS > UAS-msi flies, on day 1 and (F) day 14 after irradiation. Control 100 Gy (−) maintained without RU486, whereas msi was overexpressed in ISCs in 100 Gy (+). The result is represented as mean ± SE of at least 10 guts per group. (***p < 0.001 by t-test). (G) Exposure to ionizing radiation causes DNA damage, that increases apoptosis in the gut, coupled with reduced ISC proliferation. This loss in tissue homeostasis leads to an increase in intestinal permeability, which causes reduced survival perhaps due to systemic infection caused by commensal microbiota. The msi over expression in ISCs targets mRNAs like AC13E by binding to its 3′UTR, reducing its levels in ISCs which restores stem cell proliferation which not only reduces intestinal permeability but also increases survival.

Msi is an RNA binding protein that modulates the expression of target genes post-transcriptionally by binding to a consensus sequence called Musashi Binding Element (MBE) in the 3′UTR of target mRNAs97. Hence, to understand the mechanism by which msi modulates the ISC proliferation in response to radiation, in silico analysis was performed to identify MBE sites in the 3′UTR of Drosophila genes using RBPmap, a web resource developed to identify regulatory RNA motifs and functional sites98. Genes with 4 or more binding sites in the 3′UTR were shortlisted (Table S1), and the Smurf assay was performed to test if their knockdown in ISCs would rescue intestinal permeability, amongst the candidates tested (Supplementary Fig. 6A), Ac13E knockdown significantly reduced intestinal permeability measured by Smurf assay 14 days after irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 6B).

As the In silico analysis identified MBE sites in the 3′UTR of Drosophila genes using RBPmap identified 4 repeats of MBE sites in the Ac13E 3′UTR (Supplementary Fig. 6C). We performed RIP-ChIP analysis to determine whether Msi physically interacted with the Ac13E 3′UTR. Since our msi overexpression fly strain was tagged with HA, we pulled down the mRNAs bound to Msi using anti-HA antibody. The RIP-associated sequences were detected by qRT-PCR using primers encompassing the predicted MBE sites in the 3′UTR of Ac13E, and a three-fold enrichment was observed compared to control flies (without RU486) (−) (Supplementary Fig. 6D). We hypothesized that knockdown of the candidate gene, Ac13E, would recapitulate msi overexpression in terms of radiation-induced gut permeability and reparative proliferation. While Ac13E knockdown in ISCs significantly increased ISC proliferation 14 days after irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 5E), it had no effect on ISC proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 5F) in non-irradiated flies.

Finally, our data suggest the model (Fig. 6G) showing that tissue damage caused by genotoxic stress leads to increased apoptosis of the intestinal enterocytes as well as ISCs and, coupled with lack of ISC proliferation, which increased intestinal permeability, and reduced survival perhaps due to systemic infection caused by commensal microbiota. The ectopic expression of msi in ISCs restores stem cell proliferative repair by targeting Ac13E mRNA (and possibly other targets) that restores barrier function, thus reducing exposure to commensal microbiota and increased survival.

Discussion

Understanding the mechanisms involved in tissue homeostasis and repair in response to age-related genotoxic stress is critical for developing therapeutics against the side effects of chemotherapeutic agents. However, the lack of an expedient in vivo model has hampered progress in the field. We have developed adult Drosophila melanogaster as a model to study how the interaction between different cells help mount a response to genotoxic stress to maintain tissue homeostasis and repair. We leveraged the conservation of the fly intestine to characterize the effect of ionizing radiation on ISC proliferation and intestinal permeability. Our GWAS analysis in these lines identified msi as a potential candidate. Further results showed that the levels of msi in ISCs correlated with ISC proliferation and ectopic expression of msi in ISC not only reduced intestinal permeability but also increased survival in response to irradiation.

Earlier studies have shown that exposure to radiation in adult female flies affects fecundity and increased chromosomal aberrations in the progeny99. However, little is known regarding the long-term effect of ionizing radiation on survival of adult flies. Consistent with previous studies, our results demonstrated that flies were quite resistant to tissue damage caused by ionizing radiation100,101. Since, exposing flies to staggered doses of radiation, may be more representative of patients undergoing radiation therapy, we exposed flies to either a staggered (4 doses of 25 Gy every other day) or a single dose of 100 Gy. We found that in both exposure regimes, gut permeability was enhanced, and survival was reduced. The effect of radiation on survival was independent of sex as results were consistent between male and female flies.

Since we exposed whole flies to radiation, we expected a strong physiological readout that might explain the shortened survival of irradiated flies. We observed a consistent increase in the phosphorylation of γ-H2Av, the fly orthologue of H2AX62. We also observed elevated intestinal permeability and smaller intestines. As increased gut permeability has previously been associated with reduced survival55,102 due to increased local and systemic inflammation, we performed the Smurf assay, which demonstrated that irradiated flies have highly permeable intestines. In addition, we observed elevated inflammation in the intestine quite early after irradiation, followed by increased systemic inflammation that temporally correlated with increased intestinal permeability (by day 14 after irradiation). Our results are consistent with previous observations that increased intestinal permeability leads to increased risk of mortality due to bacterial infection55.

Importantly, leaky gut syndrome is a hallmark of radiation enteritis in human patients undergoing radiation therapy103,104. In humans, the detrimental responses to radiation treatment vary greatly103,104 and survival, health, and gut homeostasis may at least in part be regulated by genetic factors80,83,84. Thus, we reasoned that fully sequenced natural variants from the DGRP collection would identify novel genes that could restore intestinal homeostasis in irradiated flies. Interestingly, we observed a significant decline in proliferating ISCs, which reduced ISCs numbers in the irradiated flies. The reduced ability of fly ISCs to proliferate in response to radiation-induced damage in the gut is similar to that observed in mammals32–35 and even patients receiving radiation or chemotherapy105. So, we reasoned that the dual effect of radiation on increased apoptosis in the intestine and reduction in reparative proliferation might be responsible for increased intestinal permeability in irradiated flies. We determined if forcing the restoration of ISC populations might have a protective effect in irradiated flies. In flies, Cyclin E alone is capable of activating re-entry into S-phase and promoting ISC proliferation106. In addition, overexpression of Cyclin E promotes proliferation in cells96. Our results confirmed that over-expression of CycE in ISCs not only promoted ISC proliferation but also improved intestinal barrier function.

Our studies identified msi as one of the modulators of ISC proliferation in response to radiation. Msi, a highly conserved RNA binding protein, is a regulator of post-transcriptional processing of target genes97, as well as a known stem cell marker94. It was first identified as a regulator of asymmetric division sensory organ precursor cells in Drosophila107. We found that modulating msi in ISCs affected ISC proliferation, which is consistent with the human orthologue, msi1 that is strongly expressed in the intestinal crypts, especially during embryonic development and regeneration91. Interestingly, msi overexpression did not significantly impact survival in non-irradiated flies. The stem cell-specific role of msi was further confirmed since its ectopic expression in enterocytes had no effect on intestinal permeability. Interestingly, msi1 knockdown in U-251 (human glioblastoma cell line) resulted in higher instances of double-stranded breaks108, suggesting its role in DNA repair. Another study in mice demonstrated that msi1 and msi2 could regulate stem cell activation and self-renewal of crypt base columnar cells upon tissue damage, thus indicating a conserved effect of msi on ISC function109, none the less our findings in conjunction to these reports point to a critical role of Musashi in regenerative medicine.

Musashi regulates target genes by binding to the 3′UTR of its target. It has previously shown to regulate simA however we did not observe any protective effect of simA knockdown on intestinal permeability in irradiated flies (Supplementary Fig. 6A). However, our results show targeting of Ac13E is post transcriptionally regulated by Msi. The Ac13E is an Adenylate cyclase (DAC9) that catalyzes the synthesis of cAMP from ATP, yielding diphosphate as a by-product and its human homologue is ADCY9110. It has previously been shown to be involved in elementary associative learning and is responsive to Ca2+/Calmodulin111. Its role in intestinal permeability is not known, however the increased levels of its human homologue (Adenylyl Cyclase 9) is considered as a prognostic marker in patients with colon cancer112. In addition, cyclic AMP produced in the enteroendocrine cells has been shown to be essential for ISC quiescence in Drosophila intestine113. Our results demonstrate that Musashi binds to and regulates Ac13E expression. In addition, knocking down Ac13E in the ISCs not only increased the ISC proliferation, it also significantly reduced intestinal permeability, thus suggesting a novel regulatory pathway. Taken together, we propose that that Musashi restores intestinal barrier function by enhancing ISC proliferation and tissue repair in response to radiation by targeting Ac13E mRNA (Fig. 6G).

Methods

Fly culture, stocks and lifespan analysis

Flies were reared on standard laboratory diet (Caltech food recipe: 8.6% Cornmeal, 1.6% Yeast, 5% Sucrose, 0.46% Agar, 1% Acid mix)114,115. Eclosed adults were transferred within 3–5 days to the yeast extract (YE) diet (1.5% YE, 8.6% Cornmeal, 5% Sucrose, 0.46% Agar, 1% Acid mix). For Gene-Switch Gal4 drivers, RU486 was dissolved in 95% ethanol with a final concentration of 100 μM (the media is then referred to as ‘+RU486’) and was administered from the adult stage (5 day old). The control diet contained the same volume of 95% ethanol and is referred to as '−RU486’. Life spans were analyzed as described previously114,116. At least 150 flies were used for the life span analysis. The following fly strains were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila stock center: UAS-msi RNAi (BL55152), UAS-Ac13E RNAi (BL62247), UAS-CycE (BL4781). UAS-msi-HA (F004549) was obtained from FlyORF. UAS-CD8-PARP-Venus was a gift from Dr. Masayuki Miura, 5961-GS and 5966-GS from Dr. Heinrich Jasper, esg-Gal4, UAS-GFP from Dr. Shigeo Hayashi, upd3-Gal4 from Dr. Norbert Perrimon.

Radiation exposure

Adult, female, 5-day old flies were exposed to different doses of X-rays at 320 kV and 10 mA to achieve the required doses as indicated and maintained on a standard fly diet.

Quantitative real-time-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from at least 12 female guts, 8 female fat bodies (fly abdomen) or 5 female whole flies using Quick-RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research) per preparation. The cDNA was synthesized using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN) using 1 µg of total RNA per sample. The qPCR reaction was performed in duplicate on each of at least 3 independent biological replicates using SensiFAST SYBR No-ROX Kit (BIOLINE). Error bars indicate standard deviation. Samples were normalized with ribosomal protein 49 (rp 49).

Primer sequences

rp 49-F: 5′-CCACCAGTCGGATCGATATG-3′

rp 49-R: 5′-CACGTTGTGCACCAGGAACT-3′

Diptericin-F: 5′-GGCTTATCCGATGCCCGACG-3′

Diptericin-R: 5′-TCTGTAGGTGTAGGTGCTTCCC-3′

Drosomycin-F: 5′-GAGGAGGGACGCTCCAGT-3′

Drosomycin-R: 5′-TTAGCATCCTTCGCACCAG-3′

hid-F: 5′-CGATGTGTTCTTTCCGCACG-3′

hid-R: 5′-TGCTGCCGGAAGAAGTTGTA-3′

reaper-F: 5′-CATACCCGATCAGGCGACTC-3′

reaper-R: 5′-ACATGAAGTGTACTGGCGCA-3′

puckered-F: 5′-CGGGAACGGGGTAAATCCAA-3′

puckered-R: 5′-GAGCAGTTACTACCCGCCAG-3′

upd3-F: 5′-ACCTACAGAAGCGTTCCAG-3′

upd3-R: 5′-GGTTCTGTAGATTCTGCAGG-3′

Immunohistochemistry and histology

Immunohistochemistry and histology were performed using protocol previously described117,118. For immunohistochemistry, flies were dissected in PEM (100 mM Pipes, 2 mM EGTA and 1 mM MgSO4). Dissected guts were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PEM for 45 min. Samples were washed for 10 min three times with PEM then incubated with 1% NP40/PEM for 30 min. Samples were washed for 10 min three times with TBS-TB (20 mM Tris–HCl, 130 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.2% BSA) and blocking was performed with 5% goat serum in TBS-TB for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, were then washed for 10 min three times with TBS-TB and incubated with secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained using DAPI. Samples were mounted with Mowiol mounting buffer and analyzed by fluorescence microscope (KEYENCE: BZ-X710). Images were taken at the posterior midgut (region R4). The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-rabbit GFP (Life technologies: 1/500), anti-rabbit phospho-histone H3 (Millipore: 1/1,000), anti-mouse β-galactosidase (Promega: 1/250), anti-mouse γ-H2Av (DSHB: 1/500), anti-rabbit Cleaved PARP (Cell Signaling Technology: 1/100), anti-rabbit Alexa fluor 488 (Cell Signaling Technology: 1/500), anti-mouse Alexa fluor 555 (Cell Signaling Technology: 1/500), anti-rabbit Alexa fluor 555 (Cell Signaling Technology: 1/500) and anti-mouse Alexa fluor 647 (Invitrogen: 1/500).

For histology, flies were washed in 70% ethanol solution for 1 min. Heads without proboscis were fixed in fresh Carnoy’s fixative (ethanol: Chloroform: acetic acid at 6:3:1) overnight at 4 °C. They were then consecutively washed at RT with 30, 50, 70, 90 and 100% EtOH for 10 min each; following which they were transferred to methyl benzoate (MB) for 30 min at RT and to MB: paraffin at 1:1 ratio for 1 h at 65 °C. Heads were then incubated twice for 1 h at 65 °C in melted paraffin and embedded in paraffin blocks. The blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 5 nm, subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining, and examined by brightfield microscopy.

Acridine orange staining

Dissected guts were incubated with Ethidium Bromide and acridine orange (Sigma: 5 µg/ml) (10 µg/ml) in PBS for 5 min at room temperature. Samples were rinsed with PBS twice, then mounted with PBS and immediately analyzed by microscope (Olympus: BX51).

SYTOX orange nucleic acid staining

Dead cells were observed by SYTOX staining as previously described117. Dissected guts were incubated with SYTOX Orange Nucleic Acid Stain (Invitrogen: 1 μM) and Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen: 10 μg/ml) in PEM for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were rinsed with PEM twice, then mounted with PEM and immediately analyzed by microscope (KEYENCE: BZ-X710).

Smurf gut permeability assay

We performed the assay as previously described with slight modifications55. Briefly, 25 flies were placed in an empty vial containing a piece of 2.0 cm × 4.0 cm filter paper. 300 µl of blue dye solution, 2.5% blue dye (FD&C #1) in 5% sucrose, was used to wet the paper as a feeding medium. Smurf and non-smurf flies were counted following incubation with feeding paper for 24 h at 25 °C. Smurf flies were quantified as flies with any visible blue dye outside of the intestines.

Spontaneous activity

24 h after irradiation, flies (four vials per group with 25 flies in each vial) were placed in population monitors and their physical activity was recorded every 10 min for 24 h (Drosophila population monitor by Trikinetics Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Reading chambers have circular rings of infrared beams at three different levels, which allow recording whenever a fly crosses the rings. Activity monitors were kept in temperature-controlled incubators set at 25 °C on a 12-h light–dark cycle. The daylight period began at 8:00 a.m.

Screening for variants associated with regulating irradiation-induced phenotypes

We preformed Genome-Wide Association Study as previously described by Nelson et al.119. Briefly, 2 weeks following irradiation, we observed significant variation in the gut permeability Smurf assay between DGRP lines in the proportion of Smurf flies. Candidates with a false detection rate (FDR) of 27% or less were considered for further validation. FDRs were calculated empirically from permuted data89. The association was determined by aligning phenotypic values at an allelic marker. Genetic markers with > 25% minor allele frequency were used by employing custom scripts written in Python, using ordinary least squares regression from the stats models module88. The analysis was done using linear model: phenotype = β1xGenotype + β2xIrradiationDose + β3xGenotype X-Irradiation Dose + intercept. The p-values shown reflect whether the β term is 0. The Genotype X-Irradiation Dose term reflects the Irradiation-dependent portion of genetic influence on the phenotype88.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) and FlyORF for providing the fly strains. We also thank members of the Kapahi lab for discussions and suggestions and Geoffrey Meyerhof for editing the manuscript. This work was funded by grants from the American Federation for Aging Research and Hillblom foundations (P.K.), and the NIH (R01AG038688 & R01AG045835) (P.K.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, P. K., K.A., and A.S.; Methodology, A.S., K.A., and P.K., R.B.; Investigation, A.S., K.A., B.P., K.A.W., C.N., M.W., E.M., A.H. and M.O.; Writing—review & editing, P.K., A.S. and K.A.; Funding acquisition, P.K.; Resources, P.K., R.B.; Supervision, P.K., R.B.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Amit Sharma and Kazutaka Akagi.

Contributor Information

Amit Sharma, Email: amit.sharma@sens.org.

Kazutaka Akagi, Email: kazuakg@ncgg.go.jp.

Pankaj Kapahi, Email: pkapahi@buckinstitute.org.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-75867-z.

References

- 1.Barnes DE, Lindahl T. Repair and genetic consequences of endogenous DNA base damage in mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:445–476. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azzam EI, Jay-Gerin JP, Pain D. Ionizing radiation-induced metabolic oxidative stress and prolonged cell injury. Cancer Lett. 2012;327:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H, Mitchell JR, Hasty P. DNA double-strand breaks: A potential causative factor for mammalian aging? Mech. Ageing Dev. 2008;129:416–424. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White RR, Vijg J. Do DNA double-strand breaks drive aging? Mol. Cell. 2016;63:729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang D, Wang HB, Brinkman KL, Han SX, Xu B. Strategies for targeting the DNA damage response for cancer therapeutics. Chin. J. Cancer. 2012;31:359–363. doi: 10.5732/cjc.012.10087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ljungman M. Targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2929–2950. doi: 10.1021/cr900047g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell SN, Bindra RS. Targeting the DNA damage response for cancer therapy. DNA Repair. 2009;8:1153–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Connor MJ. Targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castedo M, et al. Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: A molecular definition. Oncogene. 2004;23:2825–2837. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaupel P. Tumor microenvironmental physiology and its implications for radiation oncology. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2004;14:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez-Millan J, et al. The importance of bystander effects in radiation therapy in melanoma skin-cancer cells and umbilical-cord stromal stem cells. Radiother. Oncol. 2012;102:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joye I, Haustermans K. Early and late toxicity of radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer. 2014;203:189–201. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-08060-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu Y, Zhou J, Tao G. Molecular aspects of chronic radiation enteritis. Clin Investig. Med. 2011;34:E119–E124. doi: 10.25011/cim.v34i3.15183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Accordino MK, Neugut AI, Hershman DL. Cardiac effects of anticancer therapy in the elderly. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:2654–2661. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourgier C, et al. Late side-effects after curative intent radiotherapy: Identification of hypersensitive patients for personalized strategy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelley MR, Logsdon D, Fishel ML. Targeting DNA repair pathways for cancer treatment: What's new? Future Oncol. 2014;10:1215–1237. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard SM, Yanez DA, Stark JM. DNA damage response factors from diverse pathways, including DNA crosslink repair, mediate alternative end joining. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1004943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C, et al. Cell cycle control, DNA damage repair, and apoptosis-related pathways control pre-ameloblasts differentiation during tooth development. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:592. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1783-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corcoran NM, Clarkson MJ, Stuchbery R, Hovens CM. Molecular pathways: Targeting DNA repair pathway defects enriched in metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:3132–3137. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.d’Adda di Fagagna F. Living on a break: Cellular senescence as a DNA-damage response. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:512–522. doi: 10.1038/nrc2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Childs BG, Baker DJ, Kirkland JL, Campisi J, van Deursen JM. Senescence and apoptosis: Dueling or complementary cell fates? EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1139–1153. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bardin AJ, Perdigoto CN, Southall TD, Brand AH, Schweisguth F. Transcriptional control of stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila intestine. Development. 2010;137:705–714. doi: 10.1242/dev.039404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang J, Balachandra S, Ngo S, O'Brien LE. Feedback regulation of steady-state epithelial turnover and organ size. Nature. 2017;548:588–591. doi: 10.1038/nature23678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stacey R, Green JT. Radiation-induced small bowel disease: Latest developments and clinical guidance. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2014;5:15–29. doi: 10.1177/2040622313510730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shadad AK, Sullivan FJ, Martin JD, Egan LJ. Gastrointestinal radiation injury: Prevention and treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013;19:199–208. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leulier F, Royet J. Maintaining immune homeostasis in fly gut. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:936–938. doi: 10.1038/ni0909-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochoa-Reparaz J, Mielcarz DW, Begum-Haque S, Kasper LH. Gut, bugs, and brain: Role of commensal bacteria in the control of central nervous system disease. Ann. Neurol. 2011;69:240–247. doi: 10.1002/ana.22344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Micchelli CA, Perrimon N. Evidence that stem cells reside in the adult Drosophila midgut epithelium. Nature. 2006;439:475–479. doi: 10.1038/nature04371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane SW, Williams DA, Watt FM. Modulating the stem cell niche for tissue regeneration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:795–803. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayyaz A, Jasper H. Intestinal inflammation and stem cell homeostasis in aging Drosophila melanogaster. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013;3:98. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chatterjee M, Ip YT. Pathogenic stimulation of intestinal stem cell response in Drosophila. J. Cell. Physiol. 2009;220:664–671. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, et al. Mitigation effect of an FGF-2 peptide on acute gastrointestinal syndrome after high-dose ionizing radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010;77:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu W, et al. PUMA regulates intestinal progenitor cell radiosensitivity and gastrointestinal syndrome. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koukourakis MI. Radiation damage and radioprotectants: New concepts in the era of molecular medicine. Br. J. Radiol. 2012;85:313–330. doi: 10.1259/bjr/16386034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poglio S, et al. Adipose tissue sensitivity to radiation exposure. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174:44–53. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.James AA, Bryant PJ. A quantitative study of cell death and mitotic inhibition in gamma-irradiated imaginal wing discs of Drosophila melanogaster. Radiat. Res. 1981;87:552–564. doi: 10.2307/3575520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaklevic BR, Su TT. Relative contribution of DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoints, and cell death to survival after DNA damage in Drosophila larvae. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, Jones DL. The effects of aging on stem cell behavior in Drosophila. Exp. Gerontol. 2011;46:340–344. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong AW, Meng Z, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway in intestinal regeneration and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;13:324–337. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kux K, Pitsouli C. Tissue communication in regenerative inflammatory signaling: Lessons from the fly gut. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014;4:49. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abrahamson S, Friedman LD. X-ray induced mutations in spermatogonial cells of Drosophila and their dose-frequency relationship. Genetics. 1964;49:357–361. doi: 10.1093/genetics/49.2.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eeken JC, et al. The nature of X-ray-induced mutations in mature sperm and spermatogonial cells of Drosophila melanogaster. Mutat. Res. 1994;307:201–212. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bownes M, Sunnell LA. Developmental effects of X-irradiation of early Drosophila embryos. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1977;39:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parashar V, Frankel S, Lurie AG, Rogina B. The effects of age on radiation resistance and oxidative stress in adult Drosophila melanogaster. Radiat. Res. 2008;169:707–711. doi: 10.1667/RR1225.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noal S, et al. One-year longitudinal study of fatigue, cognitive functions, and quality of life after adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011;81:795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gulliford SL, et al. Dosimetric explanations of fatigue in head and neck radiotherapy: An analysis from the PARSPORT Phase III trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2012;104:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Courtier N, et al. A prognostic tool to predict fatigue in women with early-stage breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. Breast. 2013;22:504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geinitz H, et al. Fatigue, serum cytokine levels, and blood cell counts during radiotherapy of patients with breast cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2001;51:691–698. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01657-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smets EM, et al. Fatigue and radiotherapy: (A) experience in patients undergoing treatment. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;78:899–906. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faithfull S. Fatigue in patients receiving radiotherapy. Prof. Nurse. 1998;13:459–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Renner M, et al. A murine model of peripheral irradiation-induced fatigue. Behav. Brain Res. 2016;307:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolff BS, Renner MA, Springer DA, Saligan LN. A mouse model of fatigue induced by peripheral irradiation. J. Vis. Exp. 2017 doi: 10.3791/55145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pfeiffenberger C, Lear BC, Keegan KP, Allada R. Locomotor activity level monitoring using the Drosophila Activity Monitoring (DAM) System. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pereira MT, Malik M, Nostro JA, Mahler GJ, Musselman LP. Effect of dietary additives on intestinal permeability in both Drosophila and a human cell co-culture. Dis. Models Mech. 2018 doi: 10.1242/dmm.034520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rera M, Clark RI, Walker DW. Intestinal barrier dysfunction links metabolic and inflammatory markers of aging to death in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:21528–21533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215849110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tzou P, et al. Tissue-specific inducible expression of antimicrobial peptide genes in Drosophila surface epithelia. Immunity. 2000;13:737–748. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Myllymaki H, Valanne S, Ramet M. The Drosophila imd signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 2014;192:3455–3462. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferrandon D, et al. A drosomycin-GFP reporter transgene reveals a local immune response in Drosophila that is not dependent on the Toll pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:1217–1227. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meng X, Khanuja BS, Ip YT. Toll receptor-mediated Drosophila immune response requires Dif, an NF-kappaB factor. Genes Dev. 1999;13:792–797. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hetru C, Hoffmann JA. NF-kappaB in the immune response of Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009;1:a000232. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang H, Kambris Z, Lemaitre B, Hashimoto C. A serpin that regulates immune melanization in the respiratory system of Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:617–626. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fernandez-Capetillo O, Lee A, Nussenzweig M, Nussenzweig A. H2AX: The histone guardian of the genome. DNA Repair. 2004;3:959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Le Guen T, Ragu S, Guirouilh-Barbat J, Lopez BS. Role of the double-strand break repair pathway in the maintenance of genomic stability. Mol. Cell Oncol. 2015;2:e968020. doi: 10.4161/23723548.2014.968020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murr R. Interplay between different epigenetic modifications and mechanisms. Adv. Genet. 2010;70:101–141. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380866-0.60005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Madigan JP, Chotkowski HL, Glaser RL. DNA double-strand break-induced phosphorylation of Drosophila histone variant H2Av helps prevent radiation-induced apoptosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3698–3705. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lake CM, Holsclaw JK, Bellendir SP, Sekelsky J, Hawley RS. The development of a monoclonal antibody recognizing the Drosophila melanogaster phosphorylated histone H2A variant (gamma-H2AV) G3. 2013;3:1539–1543. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou F, Rasmussen A, Lee S, Agaisse H. The UPD3 cytokine couples environmental challenge and intestinal stem cell division through modulation of JAK/STAT signaling in the stem cell microenvironment. Dev. Biol. 2013;373:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams DW, Kondo S, Krzyzanowska A, Hiromi Y, Truman JW. Local caspase activity directs engulfment of dendrites during pruning. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:1234–1236. doi: 10.1038/nn1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takeishi A, et al. Homeostatic epithelial renewal in the gut is required for dampening a fatal systemic wound response in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2013;3:919–930. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kasibhatla S, et al. Acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB) staining to detect apoptosis. CSH Protoc. 2006 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goyal L, McCall K, Agapite J, Hartwieg E, Steller H. Induction of apoptosis by Drosophila reaper, hid and grim through inhibition of IAP function. EMBO J. 2000;19:589–597. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McEwen DG, Peifer M. Puckered, a Drosophila MAPK phosphatase, ensures cell viability by antagonizing JNK-induced apoptosis. Development. 2005;132:3935–3946. doi: 10.1242/dev.01949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ren F, et al. Drosophila Myc integrates multiple signaling pathways to regulate intestinal stem cell proliferation during midgut regeneration. Cell Res. 2013;23:1133–1146. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shaw RL, et al. The Hippo pathway regulates intestinal stem cell proliferation during Drosophila adult midgut regeneration. Development. 2010;137:4147–4158. doi: 10.1242/dev.052506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amcheslavsky A, Jiang J, Ip YT. Tissue damage-induced intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baker NE, Yu SY. The R8-photoreceptor equivalence group in Drosophila: Fate choice precedes regulated Delta transcription and is independent of Notch gene dose. Mech Dev. 1998;74:3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(98)00054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beebe K, Lee WC, Micchelli CA. JAK/STAT signaling coordinates stem cell proliferation and multilineage differentiation in the Drosophila intestinal stem cell lineage. Dev. Biol. 2010;338:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.West CM, Dunning AM, Rosenstein BS. Genome-wide association studies and prediction of normal tissue toxicity. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2012;22:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Herskind C, et al. Radiogenomics: A systems biology approach to understanding genetic risk factors for radiotherapy toxicity? Cancer Lett. 2016;382:95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Borghini A, et al. Genetic risk score and acute skin toxicity after breast radiation therapy. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2014;29:267–272. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2014.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carulli AJ, et al. Notch receptor regulation of intestinal stem cell homeostasis and crypt regeneration. Dev. Biol. 2015;402:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Apidianakis Y, Rahme LG. Drosophila melanogaster as a model for human intestinal infection and pathology. Dis. Models Mech. 2011;4:21–30. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mak KS, et al. Significance of targeted therapy and genetic alterations in EGFR, ALK, or KRAS on survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with radiotherapy for brain metastases. Neuro-oncology. 2015;17:296–302. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kap EJ, et al. Genetic variants in the glutathione S-transferase genes and survival in colorectal cancer patients after chemotherapy and differences according to treatment with oxaliplatin. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2014;24:340–347. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pacelli R, et al. Radiation therapy following surgery for localized breast cancer: Outcome prediction by classical prognostic factors and approximated genetic subtypes. J. Radiat. Res. 2013;54:292–298. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrs087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Freytag SO, et al. Prospective randomized phase 2 trial of intensity modulated radiation therapy with or without oncolytic adenovirus-mediated cytotoxic gene therapy in intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014;89:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bhatia S. Genetic variation as a modifier of association between therapeutic exposure and subsequent malignant neoplasms in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121:648–663. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mackay TF, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster genetic reference panel. Nature. 2012;482:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Palma-Guerrero J, et al. Genome wide association identifies novel loci involved in fungal communication. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Akasaka Y, et al. Expression of a candidate marker for progenitor cells, Musashi-1, in the proliferative regions of human antrum and its decreased expression in intestinal metaplasia. Histopathology. 2005;47:348–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Potten CS, et al. Identification of a putative intestinal stem cell and early lineage marker; musashi-1. Differentiation. 2003;71:28–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.700603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kaneko Y, et al. Musashi1: An evolutionally conserved marker for CNS progenitor cells including neural stem cells. Dev. Neurosci. 2000;22:139–153. doi: 10.1159/000017435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Phelps CB, Brand AH. Ectopic gene expression in Drosophila using GAL4 system. Methods. 1998;14:367–379. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Okano H, Imai T, Okabe M. Musashi: A translational regulator of cell fate. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:1355–1359. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.7.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: A changing paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:153–166. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nakamura M, Ohsawa S, Igaki T. Mitochondrial defects trigger proliferation of neighbouring cells via a senescence-associated secretory phenotype in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5264. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zearfoss NR, et al. A conserved three-nucleotide core motif defines Musashi RNA binding specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:35530–35541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.597112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Paz I, Kosti I, Ares M, Jr, Cline M, Mandel-Gutfreund Y. RBPmap: A web server for mapping binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W361–367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.King RC, Darrow JB, Kaye NW. Studies on different classes of mutations induced by radiation of Drosophila melanogaster females. Genetics. 1956;41:890–900. doi: 10.1093/genetics/41.6.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Koval TM, Myser WC, Hart RW, Hink WF. Comparison of survival and unscheduled DNA synthesis between an insect and a mammalian cell line following X-ray treatments. Mutat. Res. 1978;49:431–435. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(78)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ducoff HS. Causes of death in irradiated adult insects. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1972;47:211–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1972.tb00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tricoire H, Rera M. A new, discontinuous 2 phases of aging model: Lessons from Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0141920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nejdfors P, Ekelund M, Westrom BR, Willen R, Jeppsson B. Intestinal permeability in humans is increased after radiation therapy. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1582–1587. doi: 10.1007/BF02236743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Melichar B, et al. Gastroduodenal, intestinal and colonic permeability during anticancer therapy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:1193–1199. doi: 10.5754/hge08101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yu J. Intestinal stem cell injury and protection during cancer therapy. Transl. Cancer Res. 2013;2:384–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Knoblich JA, et al. Cyclin E controls S phase progression and its down-regulation during Drosophila embryogenesis is required for the arrest of cell proliferation. Cell. 1994;77:107–120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nakamura M, Okano H, Blendy JA, Montell C. Musashi, a neural RNA-binding protein required for Drosophila adult external sensory organ development. Neuron. 1994;13:67–81. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90460-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.de Araujo PR, et al. Musashi1 impacts radio-resistance in glioblastoma by controlling DNA-protein kinase catalytic subunit. Am. J. Pathol. 2016;186:2271–2278. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yousefi M, et al. Msi RNA-binding proteins control reserve intestinal stem cell quiescence. J. Cell Biol. 2016;215:401–413. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201604119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Iourgenko V, Kliot B, Cann MJ, Levin LR. Cloning and characterization of a Drosophila adenylyl cyclase homologous to mammalian type IX. FEBS Lett. 1997;413:104–108. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00891-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yovell Y, Kandel ER, Dudai Y, Abrams TW. A quantitative study of the Ca2+/calmodulin sensitivity of adenylyl cyclase in Aplysia, Drosophila, and rat. J. Neurochem. 1992;59:1736–1744. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yi H, et al. Elevated adenylyl cyclase 9 expression is a potential prognostic biomarker for patients with colon cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018;24:19–25. doi: 10.12659/MSM.906002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Scopelliti A, et al. Local control of intestinal stem cell homeostasis by enteroendocrine cells in the adult Drosophila midgut. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:1199–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zid BM, et al. 4E-BP extends lifespan upon dietary restriction by enhancing mitochondrial activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;139:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kapahi P, et al. Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:885–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Katewa SD, et al. Intramyocellular fatty-acid metabolism plays a critical role in mediating responses to dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 2012;16:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Akagi K, et al. Dietary restriction improves intestinal cellular fitness to enhance gut barrier function and lifespan in D. melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Maksoud E, Liao EH, Haghighi AP. A neuron-glial trans-signaling cascade mediates LRRK2-induced neurodegeneration. Cell Rep. 2019;26:1774–1786.e1774. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nelson CS, et al. Cross-phenotype association tests uncover genes mediating nutrient response in Drosophila. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:867. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3137-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.