Abstract

Postural instability is a major disabling feature in Parkinson’s disease (PD). We quantified the organization of leg and trunk muscles into synergies stabilizing the center of pressure (COP) coordinate within the uncontrolled manifold hypothesis in levodopa-naïve patients with PD and age-matched control subjects. The main hypothesis was that changes in the synergic control of posture are present early in the PD process even before levodopa exposure. Eleven levodopa-naïve patients with PD and 11 healthy controls performed whole-body cyclical voluntary sway tasks and a self-initiated load-release task during standing on a force plate. Surface electromyographic activity in 13 muscles on the right side of the body was analyzed to identify muscle groups with parallel scaling of activation levels (M-modes). Data were collected both before (“off-drug”) and approximately 60 min after the first dose of 25/100 carbidopa/levodopa (“on-drug”). COP-stabilizing synergies were quantified for the load-release task. Levodopa-naïve patients with PD showed no COP-stabilizing synergy “off-drug”, whereas controls showed posture-stabilizing multi-M-mode synergy. “On-drug”, patients with PD demonstrated a significant increase in the synergy index. There were no significant drug effects on the M-mode composition, anticipatory postural adjustments, indices of motor equivalence, or indices of COP variability. The results suggest that levodopa-naïve patients with PD already show impaired posture-stabilizing multi-muscle synergies that may be used as promising behavioral biomarkers for emerging postural disorders in PD. Moreover, levodopa modified synergy metrics differently in these levodopa-naïve patients compared to a previous study of patients on chronic antiparkinsonian medications (Falaki et al. 2017a), suggesting different neurocircuitry involvement.

Keywords: Hand, Postural Control, Synergy, Variance, Motor equivalence

Introduction

Postural instability is among the most clinically important features in Parkinson’s disease (PD) and contributes significantly to PD-related disability. Clinically, these problems mark stage-III of PD according to Hoehn and Yahr (HY, Hoehn and Yahr 1967) and are viewed as signs of advanced disease. A number of studies, however, reported changes in aspects of postural control seen at earlier PD stages (HY stage-I and -II). For example, anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs, reviewed in Massion 1992) were seen prior to self-triggered postural perturbations (Bazalgette et al. 1986; Diener et al. 1989; Latash et al. 1995) and in indices of spontaneous postural sway (Mancini et al. 2012; Bonnet et al. 2014).

Several recent studies have documented an impairment in the neural control of postural stability in early-stage PD using the idea of posture-stabilizing multi-muscle synergies (Falaki et al. 2016, 2017a,b). Within this approach, stability of whole-body actions is analyzed within the abundant space of elemental variables associated with muscle groups and parallel scaling of activation levels addressed as “muscle modes” (M-modes, Krishnamoorthy et al. 2003a), “modules”, or “synergies” (D’Avela et al. 2003; Ivanenko et al. 2004; Ting and McPherson 2005). When the central nervous system (CNS) stabilizes a salient performance variable, such as the center of pressure (COP) coordinate during standing, inter-trial variance within the M-mode space is expected to be relatively high in directions leading to no COP shifts (within the uncontrolled manifold, UCM for this variable, Scholz and Schöner 1999) compared to directions leading to COP shifts (orthogonal to the UCM, ORT). The signature inequality between the variance indices, VUCM > VORT, has been documented in several studies of healthy persons (Krishnamoorthy et al. 2003b; Danna-dos Santos et al. 2007). The two variance indices can be reduced to a single synergy index ΔV computed as the normalized difference between VUCM and VORT (reviewed in Latash et al. 2010).

Patients with PD show impairments in stability of whole-body actions (reviewed in Latash and Huang 2015; Vaz et al. 2019), reflected in reduced differences between VUCM and VORT during steady states (reduced stability). Moreover, these differences are seen at HY stage-II, when clinical examination fails to detect signs of postural instability (Falaki et al. 2016) and improve with dopamine-replacement medication (Falaki et al. 2017a).

All the mentioned studies were in patients with PD who had been on levodopa, the gold standard dopaminergic replacement therapy, for months and sometimes years. Chronic exposure to levodopa by itself can lead to changes in the functioning of brain circuitry (Feigin et al. 2002; Hershey et al. 2003; Politis et al. 2017). Hence, it remains unknown if levodopa-naïve patients with PD would display similar impaired control of stability. The current study, as well as its prequel (a study of finger action, de Freitas et al. 2020), was designed to disambiguate the effects of levodopa from effects of the disease on indices of postural stability in PD.

In this study, we recruited levodopa-naïve patients with PD and age-matched controls. The patients were tested prior to and one hour after taking their first ever dose of levodopa. We hypothesized that patients with PD, compared to controls, would show reduced indices of synergies stabilizing COP in preparation to self-initiated unloading (Hypothesis 1) and that the first dose of levodopa would improve the indices of stability (Hypothesis 2).

In addition to testing the two main hypotheses, we explored another method of quantifying stability addressed as motor equivalence (ME, Mattos et al. 2011, 2013), indices that can be quantified in individual trials as deviations within the UCM for a salient performance variable between two phases separated by a quick action. Note that recent studies have confirmed high test-retest reliability of the ME index (Freitas et al. 2018) and this method requires half as many trials as the indices of inter-trial variance for achieving reliable estimates (de Freitas et al. 2019). We expected ME to show effects similar to those for VUCM (cf. Falaki et al. 2017b) with respect to both effects of levodopa-naïve patients with PD and the first dose of levodopa (Hypothesis 3).

Methods

Participants

Eleven patients with PD (7 females; aged 62.8 ± 10.5 years, mean ± standard deviation, SD) who had never received levodopa treatment (levodopa-naïve PD) took part in the study. All subjects were diagnosed by a movement disorder specialist and, on the day of the experiment, they were clinically assessed by an expert research coordinator. The patients with PD did not show clinical postural instability and had no history of recent falls. One patient showed positive signs on the pull-back test of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), Part III and was scored as stage III according to the Hoehn and Yahr scale (1967). Participant’s characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Three patients were taking non-levodopa anti-PD medication [S6 was taking 5 mg, bid, of Selegiline; S7 was taking 100 mg, tid, of Amantadine; and, S10 was on Pramipexole (ER 4.5 mg/day, and 0.25 mg, bid) and Selegiline (5 mg, bid)]. The first eight levodopa-naïve patients with PD in Table 1 agreed to take the very first carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 dose as part of the experiment and were assessed twice, in the morning (“off” levodopa) and approximately two hours after taking the medication (at lunch time, “on” levodopa). Levodopa-naïve patients with PD were prescribed Sinemet and agreed to start their first dose on the day of the experimental sessions. Participants brought their prescribed Sinemet on the day of the study visit and took one carbidopa/levodopa (25/100) after the first experimental session (see below) at lunch time in the presence of the research coordinator. The participant then went to lunch before returning to complete the second experimental session. Three patients with PD on other non-levodopa anti-PD drugs opted not to take levodopa (although they were prescribed to take it) and were assessed only once in the morning. A group of 11 age- and gender-matched healthy individuals served as controls (7 females; aged 62.4 ± 8.6 years). They had no neurological or musculoskeletal disorder. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision and gave written informed consent according to the protocol approved by the Penn State Hershey Institutional Review Board prior to their participation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Hand | Age (years) | Sex | Mass (kg) | Height (m) | HY | UPDRS-III | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | ‘off’ | ‘on’ | ||||||

| 1 | R | 61 | F | 73.8 | 1.73 | 1 | 8 | 7 |

| 2 | L | 70 | M | 105.1 | 1.80 | 2 | 33 | 18 |

| 3 | R | 70 | F | 71.1 | 1.70 | 2 | 38 | 41 |

| 4 | R | 81 | F | 93.5 | 1.55 | 2 | 34 | 32 |

| 5 | R | 53 | M | 83.6 | 1.73 | 1 | 14 | 10 |

| 6 | R | 75 | M | 74.7 | 1.75 | 2 | 34 | 30 |

| 7 | R | 68 | M | 74.7 | 1.68 | 2 | 52 | 44 |

| 8 | R | 56 | F | 77.0 | 1.73 | 3 | 25 | 24 |

| 9 | R | 53 | F | 68.1 | 1.65 | 2 | 24 | - |

| 10 | R | 49 | F | 52.5 | 1.52 | 1 | 15 | - |

| 11 | R | 55 | F | 68.0 | 1.65 | 1 | 19 | - |

| Controls | ||||||||

| 1 | R | 68 | M | 77.46 | 1.78 | |||

| 2 | R | 60 | F | 74.292 | 1.59 | |||

| 3 | R | 73 | M | 67.497 | 1.63 | |||

| 4 | L | 67 | M | 108.72 | 1.80 | |||

| 5 | R | 62 | F | 57.53 | 1.55 | |||

| 6 | R | 76 | F | 60.78 | 1.57 | |||

| 7 | L | 55 | M | 71.66 | 1.78 | |||

| 8 | R | 66 | F | 67.5 | 1.56 | |||

| 9 | R | 57 | F | 67.04 | 1.68 | |||

| 10 | R | 55 | F | 78.47 | 1.67 | |||

| 11 | R | 47 | F | 64.78 | 1.63 | |||

Note: ‘off’ and ‘on’ indicate the levodopa state for participants with PD. The shaded rows reflect those subjects who completed only the first experimental session. F/M, Female/Male; HY, Hoehn and Yahr; UPDRS-III, part 3 of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

Apparatus

During all tasks, participants were instructed to stand on the force plate (OPTIMA, AMTI, Watertown, MA) while wearing a safety harness. The platform recorded the forces and moments of force in the anterior–posterior (AP), medial-lateral (ML) and vertical (Z) direction. These data were used to calculate the instantaneous COP position in the AP direction (COPAP), which was provided as visual feedback on the 19-inch monitor screen located about 1 m away from the participant at eye level. COPAP was shown as a 0.5 cm white circle on the black background using a customized LabVIEW 2014 (National Instruments) routine.

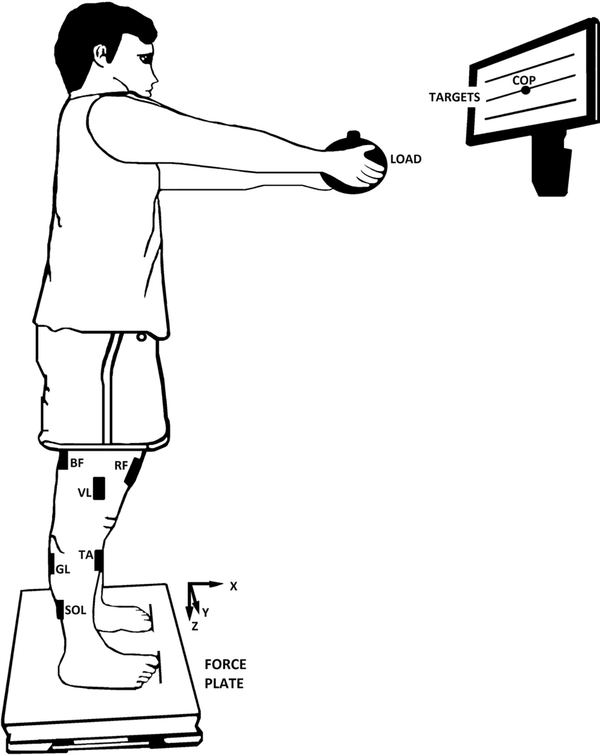

Surface electromyographic (EMG) activity of 13 muscles on the right side of the body were recorded by the Trigno Wireless System (Delsys). The signals from the electrodes were pre-amplified and band-pass filtered (20–450 Hz). EMG activity of the following muscles was recorded (Figure 1B): rectus abdominis (RA), thoracic erector spinae (EST), lumbar erector spinae (ESL), tensor fasciae latae (TFL), vastus medialis (VM), vastus lateralis (VL), rectus femoris (RF), semitendinosus (ST), biceps femoris (BF), gastrocnemius lateralis (GL), gastrocnemius medialis (GM), soleus (SOL), and tibialis anterior (TA). The electrodes were placed using disposable adhesive electrodes (3M) according to the SENIAM Project. The skin was wiped with isopropyl alcohol swabs to remove oils or dry dermis before placing the electrodes. The EMG and force platform data were recorded at a sampling frequency of 1 kHz using customized LabVIEW 2014 (National Instruments) routines.

Figure 1.

An illustration of the load-release (LR) task. Participant stood upright with the arms fully extended while holding a load. The three horizontal lines displayed on the screen represent the center of pressure (COP) targets. The central line indicated the COP coordinate during natural quiet standing and the other two lines were placed ±3 cm. The black rectangles on the right side of the body represent the positions of the electrodes: TA, tibialis anterior; SOL, soleus; GL, gastrocnemius lateralis; BF, biceps femoris; RF, rectus femoris; and, VL, vastus lateralis. The electrodes placed on the rectus abdominis (RA); thoracic erector spinae (EST); tensor fasciae latae (TFL), lumbar erector spinae (ESL), semitendinosus (ST); vastus medialis (VM); and, gastrocnemius medialis (GM) are not illustrated.

Experimental Procedures

Participants stood barefoot on the force plate with the feet at shoulder width. The position of each foot was marked on the plate and reproduced over all experimental trials. There were three postural tasks: quiet standing (QS), voluntary whole-body sway (VS), and load release (LR). For the first two tasks, participants were asked to keep their arms crossed over the chest with the fingertips resting on the shoulders.

In the QS task, participants were told to look at the blank monitor (no COP visual feedback was provided) and stand as still as possible for 61 s (one trial). The EMG data obtained from this trial were used during offline data processing. Then, the participants performed the VS task with COPAP visual feedback displayed on the monitor. The instruction was to perform whole-body voluntary sway in the AP direction, mainly about the ankle joints, and continuously move the cursor between two yellow, horizontal lines displayed on the screen; the subjects were paced at 0.5 Hz by a metronome. The lines corresponded to ±3 cm deviations from the neutral COPAP position obtained during quiet standing (Figure 1). Two familiarization trials were followed by three 35-s trials. The data from these trials were later used to identify the jointly activated muscle groups (M-modes).

During the LR task, participants stood in the same position as in the previous trials, but with their arms extended forward (shoulder flexed at 90°, elbow fully extended, forearm supinated) and palms facing upward while holding a load (Figure 1B). The load was a cylinder with the diameter of 20 cm and the mass of 2 kg for male and 1.5 kg for female participants. We used two standard loads rather than loads normalized by an individual’s weight to simplify the procedure and shorten the testing sessions. On average, the load was 2.2% of body weight for females and 2.4% of body weight for males. Participants were instructed to: a) hold the load; b) lean forward mainly about the ankle joints to a target shown on the monitor, 3 cm anterior to the initial COPAP coordinate; c) maintain this position for 2–3 s; d) release the load in a self-paced manner with a quick and small bilateral shoulder horizontal abduction movement; and e) maintain the new position of the upper limbs for 2–3 s until the experimenter announced the end of the trial.

Participants performed a few familiarization trials (typically 3–4 trials) prior to data collection. Twenty-four trials were performed, divided into two blocks of 12 trials each. Rest intervals of 2 min between blocks were allowed; fatigue was never reported by the participants.

Data processing

Force plate and EMG signals were processed off-line using a customized Matlab R2018a program (Mathworks Inc, MA, USA). Force and moment signals were filtered with a 10-Hz low-pass, fourth-order, zero-lag Butterworth filter prior to computing the COPAP time-series.

For all tasks, the raw EMG data were shifted 50 ms backward with respect to the force plate data to account for the electromechanical delay (Corcos et al. 1992). Then, the EMG data were band-pass filtered (20–350 Hz) with a fourth-order, zero-lag Butterworth filter, and fully rectified. The average value within a 5-s time interval of the muscle activity during the QS trial (EMGQS) was calculated and used for background activity correction of the filtered EMG data in the other tasks. The EMG data were normalized by the peak value (EMGPEAK) calculated from the VS task (Klous et al. 2011) as EMGNORM = (EMG − EMGQS)/EMGPEAK. The EMGNORM data from the VS task were used to define the groups of muscles with parallel scaling of activation levels referred to as M-modes.

To define the M-modes, the sway cycles during the VS task were identified as the time intervals between two consecutive valleys of the COPAP time-series. EMGNORM signals from each cycle were integrated over 50-ms time windows (∫EMGNORM) and then concatenated to create a matrix with each column corresponding to a muscle (n=13) and the rows corresponding to the samples across the sway cycles analyzed. We rejected from analysis the first and last two cycles in every trial and also any cycles that showed obvious EMG artifacts. The number of accepted cycles ranged from 24 to 46 for PD subjects and from 21 to 46 for controls. Principal component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation and factor extraction was run on the correlation matrix of the ∫EMGNORM for each participant. The first four factors (M-modes) were accepted for each subject based on the criterion of containing at least one muscle with a significant loading (absolute magnitude > 0.5; Hair et al. 1995). The total variance accounted for (VAF) by four PCs was computed.

For each LR trial, the instant of time when the load was released (t0) by the participant was defined as the time when the peak vertical force rate reached 1% of its maximal magnitude in that trial. All trials were aligned by t0 and then visually checked for accuracy. Data from each trial were used for further processing within ±1000 ms with respect to t0.

For each trial, the root mean square (RMS) of COPAP was calculated within the initial steady state (SS1, defined as the time interval from −1 to −0.8 seconds prior to t0) and about t0 (± 25 ms). The APA initiation was identified for each trial based on the changes in the magnitude of the first two M-modes (ventral and dorsal M-modes). The time when each M-mode deviated from its mean during SS1 ± 2 standard deviations (SD) and remained above or below the mean until t0 was defined. The time of each M-mode was visually checked for accuracy and then the earliest value was used as the APA initiation time.

Defining the Jacobian matrix

For the postural task, we assumed that small changes in the magnitude of M-modes (ΔM) were linearly related to the COPAP shifts (ΔCOP; Danna-dos-Santos et al. 2007; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2003b). The M-modes and COP changes were computed within the 50-ms time windows in the VS task and then multiple regression analysis was run to define the Jacobian matrix (J) for each subject separately:

The null-space of J served as a linear approximation of the UCM, spanned by the vectors εi, solving: J.εi = 0, used in further analysis of variance and motor equivalence. The coefficient of determination (R2) obtained at the stage of multiple linear regression was compared between groups.

Analysis of variance

The framework of the UCM hypothesis (Scholz and Schöner 1999) was used to quantify the inter-trial variance components in the four-dimensional M-mode space within the three-dimensional UCM (VUCM, variance preserving the COPAP position) and the one-dimensional orthogonal to the UCM space (VORT, variance affecting the COPAP position).

For each sample (i), the mean-free vectors of M-modes were calculated by subtracting the mean vector of the M-modes computed across trials () from the M-mode magnitudes (M) of each trial . Then the vectors were projected onto the UCM and ORT spaces:

The inter-trials variance of these projections within (VUCM) and orthogonal (VORT) to the UCM, per dimension within each subspace during the SS phase and around the time of load release (25ms prior and after t0), were computed as:

where fUCM is the parallel component and fORT is the orthogonal component, n is the number of M-modes (n = 4) and d is the dimension of the performance variable (d = 1). An index of synergy was calculated as ΔV = (VUCM – VORT)/VTOT, where VTOT is total variance. The ΔV values were further log-transformed using a modified Fisher’s z-transform, resulting in ΔVZ (Solnik et al. 2013).

Motor equivalence (ME) analysis

In the ME analysis, the magnitudes of M-mode deviation within the UCM (motor equivalent, ME) and orthogonal to the UCM (non-motor equivalence, nME) were calculated. The ME and nME indices were computed between SS1 and a 200-ms time interval after load release, 800–1000 ms after t0 referred to as SS2.

In each trial, the vectors of M-modes deviation (ΔM) were projected onto the UCM and ORT spaces and normalized by the square root of the dimension in the respective spaces (Mattos et al. 2011, 2013).

Further, ME and nME were averaged across trials for each subject.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were run using IBM-SPSS 25 (Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.). The normality of the data distributions for each outcome variable was tested with the Shapiro-Wilks test before further analysis. Most outcome variables related to the PD effects did not violate the normality assumption and were analyzed using parametric methods; exceptions were UPDRS-III, VAF, and R2 that were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U.

To assess the effects of disease, one-way ANOVA was run on the effect of group (levodopa-naïve patients with PD vs. controls, with 11 participants in each group) on the time of APA initiation. Two two-way ANOVAs (Group × Time-Interval: SS vs. time interval about t0), with the last factor considered as repeated measures (RM), were performed on COPAP variability and ΔVZ. Two three-way (Group × Time-Interval × Component: UCM vs. ORT) ANOVAs, with the last two factors as RM, were performed on the variance (VUCM and VORT) and motor equivalence (ME and nME) indices. Pairwise contrasts with Bonferroni corrections were applied to explore significant interaction effects.

To examine the effects of the first dose of levodopa, one-way RM ANOVA was run to test the effect of drug (“off” levodopa vs. “on” levodopa, N=8) on the time of APA initiation for comparison between medication states. Two two-way RM ANOVAs (Drug × Time-Interval) were performed on COPAP variability and ΔVZ. Two three-way RM ANOVAs (Drug × Time-Interval × Component: UCM vs. ORT) were performed on the variance (VUCM and VORT) and motor equivalence (ME and nME) indices. For all statistical tests, the alpha level was set at 0.05.

Results

Effects of disease

All participants were able to successfully complete the postural tasks. There were no differences in age (PD: 62.8 ± 10.5 and controls: 62.4 ± 8.6 years), mass (PD: 76.5 ± 13.9 and controls: 72.3 ± 13.7 kg), or height (PD: 1.68 ± 0.08 and controls: 1.66 ± 0.09 m) between participants with PD and controls.

Task performance

During the load release (LR) task, the variability (RMS) of the COPAP coordinate within the SS interval and within ±25 ms with respect to t0 were averaged across trials and compared between groups. The RMS values were smaller for the PD group compared to the control group for both time intervals, i.e., SS (0.049 ± 0.006 and 0.074 ± 0.009 cm, for the PD and controls, respectively) and around t0 (0.019 ± 0.002 and 0.031 ± 0.004 cm for the PD and controls, respectively). The RMS values were larger during the SS time interval than during the interval about t0. This was confirmed by the significant effects of Group and Time-Interval without an interaction. Statistical results for the effects of disease are presented in Table 2. COPAP shifts from the SS interval to t0 were similar in the two groups (0.19 ± 0.04 and 0.20 ± 0.09 cm). The time series of the COPAP and the first two of the four modes (see later) for a representative participant of each group during the LR task are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2:

Statistical results for the Effects of Disease [PD × Controls; n=11].

| Outcome | Effects of Disease | F1,20 | p-value | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPAP RMS | ||||

| Group | 8.26 | 0.009 | 0.29 | |

| Time Interval | 49.16 | <0.001 | 0.71 | |

| Group*Time-Interval | 1.40 | 0.25 | 0.07 | |

| APA (s) | Group | 4.83 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

| Variance | ||||

| Group | 11.10 | 0.003 | 0.36 | |

| Time Interval | 1.44 | 0.24 | 0.07 | |

| Component | 1.73 | 0.20 | 0.08 | |

| Group*Time-Interval | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.01 | |

| Group*Component | 7.78 | 0.01 | 0.28 | |

| Time-Interval*Component | 0.82 | 0.38 | 0.04 | |

| Group*Time-Interval*Component | 2.29 | 0.15 | 0.10 | |

| Synergy index (ΔVZ) | ||||

| Group | 8.59 | 0.008 | 0.30 | |

| Time Interval | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.02 | |

| Group*Time-Interval | 1.31 | 0.27 | 0.06 | |

| Motor Equivalence | ||||

| Group | 0.36 | 0.56 | 0.02 | |

| Component | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.02 | |

| Group*Component | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.04 | |

Note: COPAP, center of pressure in the anterior-posterior direction. For the factor Time-Interval, the levels were SS and the time interval about t0. The levels for the factor Component were variance within (VUCM) and orthogonal (VORT) to the UCM. For Motor Equivalence, the levels for the factor Component were motor and non-motor equivalence values. Significant effects are presented in bold.

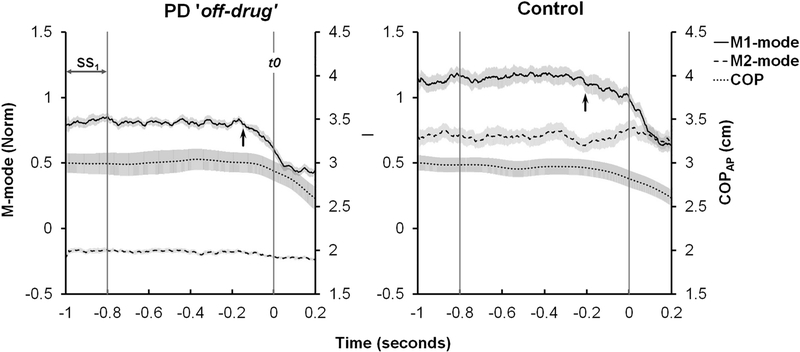

Figure 2.

Average across trials time series of the COPAP and first two M-modes for representative participants of the PD (left graph) and Control (right graph) groups during the load release task. Error shades show standard errors. The vertical lines indicate the steady state, SS1, interval and the time when the load was released, t0. The arrow pointing at the M1-mode line in each graph indicates the time of APA initiation.

M-mode identification

Four M-modes were identified from the voluntary sway task data using PCA with rotation and factor extraction. The total variance accounted for (VAF) by these modes was greater for the controls compared to the PD group (Mann–Whitney U = 28, p = 0.033). The median VAF values were 67.4% (IQR: 62.7–74) for the PD group and 75.1% (IQR: 69.4–75.3) for the control group. The muscle loadings for each M-mode and respective VAF values for a representative participant of each group are presented in the upper part of Table 3. Overall, there were only small qualitative differences in the M-mode composition between groups.

Table 3.

Explained variance and muscle loadings for the four M-modes

| PD | Controls | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |||

| off | EV (%) | 43.4 | 12.66 | 11.23 | 7.78 | 38.19 | 18.00 | 11.30 | 7.87 | |

| Loadings | TA | −0.76 | 0.21 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.37 | 0.79 | 0.02 | −0.07 | |

| SOL | 0.90 | 0.16 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.84 | −0.33 | 0.12 | 0.04 | ||

| GM | 0.92 | 0.17 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.85 | −0.22 | 0.09 | 0.03 | ||

| GL | 0.87 | 0.12 | 0.15 | −0.01 | 0.83 | −0.26 | 0.10 | 0.00 | ||

| BF | 0.92 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.86 | −0.18 | 0.18 | −0.07 | ||

| ST | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.85 | −0.20 | 0.10 | −0.08 | ||

| RF | −0.81 | −0.09 | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.42 | 0.80 | −0.03 | −0.03 | ||

| VL | −0.25 | −0.79 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.11 | −0.23 | 0.79 | 0.03 | ||

| VM | −0.13 | −0.39 | 0.63 | −0.14 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.80 | 0.01 | ||

| TFL | −0.07 | 0.77 | 0.15 | −0.02 | −0.16 | 0.80 | −0.27 | 0.02 | ||

| ESL | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.79 | −0.24 | 0.21 | 0.00 | ||

| EST | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.73 | 0.14 | 0.61 | −0.13 | 0.08 | 0.18 | ||

| RA | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.98 | ||

| on | EV (%) | 37.12 | 15.92 | 12.68 | 8.52 | |||||

| Loadings | TA | −0.61 | 0.50 | −0.25 | 0.15 | |||||

| SOL | 0.91 | −0.14 | 0.06 | 0.02 | ||||||

| GM | 0.95 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.05 | ||||||

| GL | 0.87 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.09 | ||||||

| BF | 0.84 | −0.11 | 0.20 | −0.20 | ||||||

| ST | 0.93 | −0.07 | 0.23 | 0.01 | ||||||

| RF | −0.51 | 0.66 | −0.20 | 0.05 | ||||||

| VL | 0.01 | 0.82 | −0.09 | −0.02 | ||||||

| VM | 0.09 | 0.79 | 0.10 | −0.11 | ||||||

| TFL | −0.14 | 0.04 | −0.19 | 0.80 | ||||||

| ESL | 0.23 | −0.11 | 0.77 | 0.09 | ||||||

| EST | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.84 | −0.05 | ||||||

| RA | 0.11 | −0.12 | 0.23 | 0.60 | ||||||

The data for one representative PD (off and on sessions, respectively, before and after first levodopa dose) and one Control participant are presented. EV, Explained Variance; M1-M4, M-modes; TA, tibialis anterior; SOL soleus; GM, gastrocnemius medialis; GL, gastrocnemius Lateralis; BF, biceps femoris; ST semitendinosus; RF rectus femoris; VL, vastus lateralis; VM, vastus medialis; TFL, tensor fasciae latae; ESL, lumbar erector spinae; EST, thoracic erector spinae; RA, rectus abdominis. Significant loading factors are shown in bold.

Multiple linear regression between the M-mode changes and COPAP shifts showed no difference between the groups in the adjusted median R2 values. The adjusted median R2 values were 0.77 for both groups, with the quartile ranges of 0.54–0.84 and 0.72–0.83 for the PD and control groups, respectively.

Anticipatory postural adjustments

The time of APA initiation, as defined by the earliest M-mode deviation, was delayed significantly in the PD group (−139±18.4 ms with respect to the time of action initiation) compared to the control group (−185.6±10.5 ms), confirmed by one-way ANOVA (Table 2). The APA initiation time for a representative participant of each group is shown in Figure 2 by the arrow pointing at the M1-mode.

UCM-based variance and motor equivalence analysis

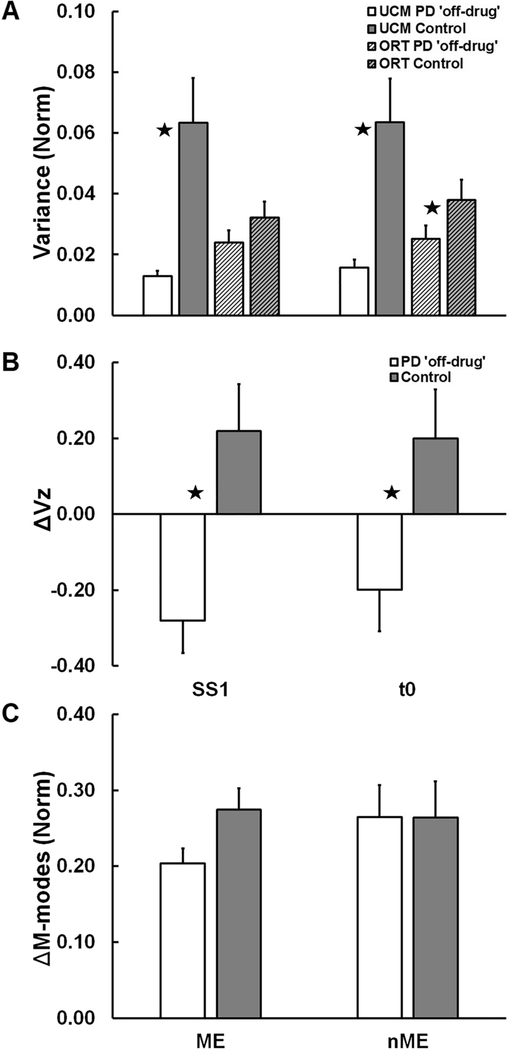

Levodopa-naïve patients with PD had a significantly lower inter-trial variance component within the UCM for the COPAP coordinate (VUCM) compared to controls (Figure 3A) during both time-intervals: SS and by the time of load release (t0±25 ms). The component affecting the COPAP coordinate (VORT), on the other hand, was similar between groups. These results were confirmed by the significant Group × Component interaction (Table 2) with the main effect of Group for VUCM (Table 2). VORT was not significantly different from VUCM for the PD group (indicating a lack of COPAP-stabilizing synergy), whereas VUCM > VORT for the control group in both time intervals (p = 0.009). There was no Time-interval effect and no interactions.

Figure 3.

Across-subject average values of: (A) variance not affecting (VUCM) and affecting (VORT) the COPAP coordinate; (B) index of synergy, ΔVZ; and (C) outcome variables of the motor equivalence analysis (ME and nME) for the PD (white and light gray filled bars) and Control groups (black and dark/gray filled bars) at the first steady state (SS1) and time interval t0±25 ms. Error bars show standard errors. Stars show significant Group effects (p < 0.05).

As a result, the index of synergy, ΔVZ, was, on average, negative for the PD group, whereas it was positive for the controls (Figure 3B; see the significant effect of Group in Table 2).

In the motor equivalence analysis, there were no significant group differences in the ME and nME indices (see Table 2 for more details) between the two steady states, before and after the load release, SS1 and SS2, although, on average, ME was higher in the control group (Figure 3C).

Effects of the first dose of levodopa

After taking their first dose of carbidopa/levodopa (25/100 mg), seven out of eight levodopa-naïve patients with PD who agreed to take their first dose as part of our study showed a reduction in the UPDRS-III score ranging from 1 to 15 points (see Table 1); the difference was significant (Z=−1.97, p=0.049).

M-modes, task performance and anticipatory postural adjustments

At the step of M-mode identification, there was only a small, non-significant increase in the VAF after taking the first drug dose (71%; IQR: 67.2–74) compared to the “off-drug” condition (65.3%; IQR: 61.4–74.3). There were no major changes in the loadings of the M-modes (bottom part of Table 3) or in the adjusted median R2 value for the “on-drug” state of the PD patients (0.79; IQR: 0.49–0.85) compared to the “off-drug” state (0.77; IQR: 0.54–0.84).

The COPAP RMS values computed within the SS interval and when the load was released (t0±25 ms) were similar between the “off-drug” and “on-drug” states, 0.046 ± 0.007 and 0.049 ± 0.009 cm, respectively as presented in Table 4 showing the statistical results for the effects of drug. The COPAP variability decreased for both medication states by the time of load release to 0.019 ± 0.002 and 0.024 ± 0.004 cm, respectively. The Time-interval effect on RMS was significant (Table 4).

Table 4:

Statistical results for the Effects of Drug (before × after first dose; n=8).

| Outcome | Effects of Drug | F1,7 | p-value | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPAP RMS | ||||

| Drug Intake | 2.23 | 0.18 | 0.24 | |

| Time Interval | 21.22 | 0.002 | 0.75 | |

| Drug Intake*Time-Interval | 0.08 | 0.79 | 0.01 | |

| APA (s) | Drug Intake | 0.44 | 0.53 | 0.06 |

| Variance | ||||

| Drug Intake | 1.07 | 0.34 | 0.13 | |

| Time Interval | 3.20 | 0.12 | 0.31 | |

| Component | 1.00 | 0.35 | 0.13 | |

| Drug Intake*Time-Interval | 2.51 | 0.16 | 0.26 | |

| Drug Intake*Component | 6.38 | 0.039 | 0.48 | |

| Time-Interval*Component | 1.25 | 0.30 | 0.15 | |

| Drug Intake*Time-Interval*Component | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.06 | |

| Synergy index (ΔVZ) | ||||

| Drug Intake | 7.13 | 0.032 | 0.51 | |

| Time Interval | 3.85 | 0.91 | 0.36 | |

| Drug Intake*Time-Interval | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.07 | |

| Motor Equivalence | ||||

| Drug Intake | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.06 | |

| Component | 0.28 | 0.61 | 0.04 | |

| Drug Intake*Component | 1.11 | 0.33 | 0.14 | |

COPAP, center of pressure in the anterior-posterior direction. For the factor Time-Interval, the levels were SS and the time interval about t0. For Component, the levels were variance within (VUCM) and orthogonal (VORT) to the UCM. For Motor Equivalence, the levels were motor and non-motor equivalence values. Significant effects are presented on bold.

After the first dose of medication, the APA initiation time was about 20 ms earlier compared to the “off-drug” state, but this difference was non-significant (Table 4): 132.8±23.4 ms in the “off-drug” state vs. 150.5±15.9 in the “on-drug” state.

UCM-based variance and motor equivalence analysis

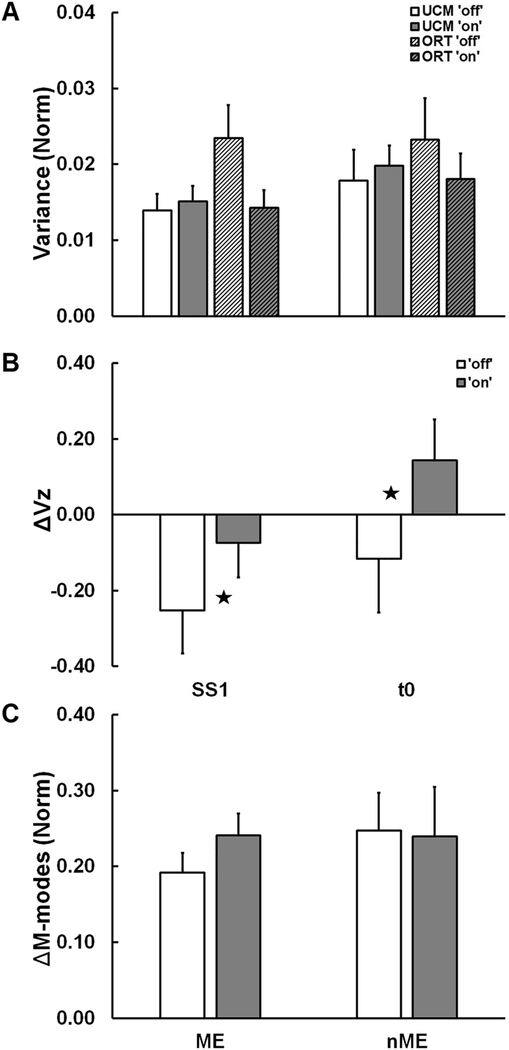

The first dose of medication affected the COP-stabilizing synergy in the M-mode space. The drug led to higher ΔVZ compared to the “off-drug” state (Figure 4B; see statistical results for the effects of drug in Table 4). ΔVZ values became less negative by the time interval t0±25 ms. There was a trend correlation between changes in the UPDRS part III and changes in the synergy index (ΔΔVZ), R = 0.69, 0.1 > p > 0.05.

Figure 4.

Across-subject average values of: (A) variance not affecting (VUCM) and affecting (VORT) the COPAP coordinate; (B) index of synergy, ΔVZ; and (C) outcome variables of the motor equivalence analysis (ME and nME) for the PD subgroup before (“off” drug state, white and light gray filled bars) and after (“on” drug state, black and dark/gray filled bars) at the steady state (SS) and around t0. Error bars show standard errors. Stars show significant Drug effects (p < 0.05).

Analysis of the two components of variance, VUCM and VORT, led to ambiguous results. There was a significant Drug × Component interaction (Table 4) but no main effects of Drug or Component (Figure 4A). There was a trend (p=0.078) toward smaller VORT “on-drug” without a change in VUCM. No effects (see Table 4 for more details) were seen on either variable, ME and nME, computed within the motor equivalence analyses (Figure 4C).

Discussion

The main result of our study is the demonstration of significant differences between levodopa-naïve patients with PD and age-matched control subjects in indices of multi-muscle synergies stabilizing COP trajectory during both steady-state standing and in preparation to self-initiated load release. These findings confirm our earlier reports on changes in multi-muscle synergy indices in PD (Falaki et al. 2016), and are consistent with our Hypothesis-1 that multi-muscle synergy changes in early PD even before levodopa exposure.

Consistent with our Hypothesis-2, the first dose of levodopa led to a significant improvement in the synergy index (ΔV). This result was expected based on an earlier study (Falaki et al. 2017a), however, the mechanisms of the ΔV increase differed between our earlier and current studies. Our earlier study in patients with PD who were on chronic levodopa treatment and were evaluated in a practically defined levodopa “off” state, showed a significant increase in the component of variance in the M-mode space that did not affect COP coordinate (VUCM) after levodopa administration. There was no significant change in the component of variance that affected the COP coordinate (VORT). In contrast, the current study in levodopa-naïve patients demonstrated a drop in VORT, but no change in VUCM after the first dose of levodopa. Thus, despite similar findings of improvement in the synergy index (ΔV), the brain mechanism underlying the observation may be different. This is consistent with prior reports that chronic levodopa treatment may modulate neurocircuitry function and its responsiveness to each dose of levodopa (Berman et al. 2016). Together, these observations point at the tantalizing possibility of using VORT and VUCM to gauge different basal ganglia circuity activity and the plasticity of responding to dopaminergic modulating treatment.

Our Hypothesis-3 was not supported by the results. There were differences between the ME indices in the predicted direction, but these differences were below the level of significance. Further, we discuss these results as reflecting differences in the analysis of variance and ME analysis (cf. Falaki et al. 2017b; de Freitas et al. 2019).

Postural control impairments in early-stage PD

Postural instability and related clinical signs of PD, such as shuffling gait, freezing of gait and falls, are typical of later stages of the disease. Indeed, Hoehn and Yahr stage-III is defined as the stage at which patients display clinically identifiable postural instability, e.g., during the shoulder-pull test (Ozinga et al. 2015). However, significant differences from healthy persons have been reported for a number of indices related to the control of vertical posture at earlier stages of PD. In particular, patients with PD show differences in indices of anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs; Mancini et al. 2009; Bleuse et al. 2008) and postural sway (Frenklach et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2018) at early disease stages (before stage III). We observed significantly shorter APAs in our levodopa-naïve PD patients. These findings extend our earlier results in patients who have been chronically treated with levodopa and support the notion that changes in APAs occur even before levodopa administration.

It is worth noting that our patients with PD showed an increase in COP RMS quantified over a short steady-state time interval. This index reflects relatively fast COP motion and cannot be compared directly to indices of postural sway, which is characterized by slow COP motion at frequencies below 1 Hz (Zatsiorsky and Duarte 1999). However, an increase in our RMS index is similar to the reported changes in indices of postural sway (Viitasalo et al. 2002; Mancini et al. 2012). Taken together, these observations point at early changes in PD in both slow and faster sway components.

Our method of quantifying postural stability is based on the idea of multi-muscle synergies that dates back to classical studies of Bernstein (1947, 1967). Within Bernstein’s hierarchical scheme of motor control, the level of synergies has two functions. First, it unites elements (such as individual muscles) into groups thus alleviating the problem of motor redundancy. Second, it organizes dynamical stability of movements. The first aspect has been studied in recent years using various methods of matrix factorization applied to correlation or covariation matrices in spaces of activation of individual muscles (Krishnamoorthy et al. 2003; d’Avella et al. 2003; Ivanenko et al. 2004; reviewed in Tresch and Jarc 2009). In our study, we used PCA with rotation and factor extraction to identify muscle groups, M-modes. Other methods, such as non-negative matrix factorization and independent component analysis, lead to comparably consistent results (Tresch et al. 2006). Our method has an important advantage of generating a set of orthogonal eigenvectors that describe the data in the muscle activation space. This is important during the second step of our analysis, which requires computation of inter-trial variance components per dimension in corresponding sub-spaces.

Patients with PD showed significantly smaller amounts of VAF for the extracted sets of four M-modes. This result suggests that, in these persons, the organization of muscles into groups was less robust compared to healthy controls. Similar findings have been reported for populations with impaired motor abilities including toddlers, healthy elderly, and patients with neurological disorders (Ivanenko et al. 2007; Allen et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2017; van Criekinge et al. 2019).

The second step of our analysis addressed the second hypothesized function of the level of synergies, i.e., ensuring dynamical stability of salient performance variables. We assumed that the COP coordinate in the anterior-posterior direction was a salient variable for the tasks used in our study (cf. Winter et al. 1998). Note that the tasks were symmetrical and involved motion and perturbation in a sagittal plane.

Healthy controls showed much higher amounts of variance compatible with an unchanged COP coordinate (VUCM) compared to the de novo patients with PD. On average, the difference was at least three-fold. No significant difference was seen in the other component of variance, VORT, resulting in positive synergy indices in the control group only. These results are comparable to those reported in an earlier study (Falaki et al. 2016). They suggest that lacking VUCM may serve as a negative predictor of balance stability. This conclusion is supported by a study of patients with multiple sclerosis who also show significantly reduced amounts of VUCM compared to age-matched controls (Jo et al. 2017).

In the past, the lack of flexibility has been mentioned as a feature of motor patterns in PD (Rodriguez et al. 2013; reviewed in Bloem et al. 2006; Hausdorff 2007). Dopamine-replacement treatment commonly leads to less stereotypical movements (Pieruccini-Faria et al. 2013; Teo et al. 2013; Workman and Thresher 2019), which have been reported to switch from overdamped to underdamped patterns (Au et al. 2010). The reduced amount of VUCM in our data also suggests insufficient inter-trial variance of muscle activation patterns, which may be causally related to the mentioned lack of movement flexibility.

Overall, our results show differences in posture-related outcome variables between control and early-stage PD subject before introduction of levodopa. These differences may be seen as reflections of primary neural circuit dysfunction, probably involving the basal ganglia- and related to the progressive loss of neurons in the substantia nigra.

Effects of first levodopa dose administration and drug withdrawal

There are two obvious major differences in the “off-drug” vs. “on-drug” comparisons between more traditional studies that use practically defined overnight drug withdrawal on the background of chronic drug treatment and our study, which explored adding a first dose of levodopa in levodopa-naïve patients with PD.

The first dose of dopamine-replacement medication led to a significant improvement in UPDRS-III scores in our PD group even though its magnitude was below the cutoff value of a 33% improvement suggested earlier (Merello et al. 2011; Schade et al. 2017). This is an expected result given the overall beneficial effect of levodopa in PD; however, the response to the first dose is highly variable (Marsden and Parkes 1977), and an earlier study has reported that acute levodopa challenge may not affect freezing of gait in PD patients (McKay et al. 2019). It is possible that, in some of the patients, the drug has not been absorbed by the gut by the testing time. Note that there was a correlation (although only a trend) between the UPDRS score and the change in the synergy index in preparation to load release (ΔΔVZ).

Patients with PD show deficits in the communication between cortical and subcortical areas, which may be compensated for partly by other brain structures (e.g., bilateral cerebellum, primary motor cortex, and prefrontal cortex; Palmer et al. 2009). Levodopa has been shown to normalize the activity in some regions (e.g., basal ganglia and thalamus) but not others (e.g., cerebellum and primary motor cortex). Hence, some have argued that dopaminergic replacement therapy is unable to revert the brain compensatory changes due to PD (Palmer et al. 2009), although it may be helpful for dysfunctions related to primary dopaminergic deficits. Nonetheless, the quick change in synergy indices observed after dopaminergic medication administration (Park et al. 2014; Falaki et al. 2017a) matches well with the known positive effects of these drugs on clinical motor metrics related to bradykinesia and rigidity (Adler et al 1997; Smulders et al 2016, Trenkwalder et al 2011). However, the cited previous studies were conducted primarily on patients with PD who had chronic levodopa exposure, which might have modulated the diseased neurocircuitry and its immediate responsiveness to levodopa.

In our first study of drug-naïve patients with PD (de Freitas et al. 2020), we observed worse individual control of fingers (higher enslaving index) and higher overall variance indices after the first levodopa dose. In the current study, we did not observe comparable effects of worsening multi-muscle synergies. However, we did observe that the overall amount of variance dropped, primarily due to the significant decrease in VORT. These observations suggest that effects of the first drug dose may be effector and/or task-specific. This preliminary conclusion requires further investigation using a broader range of tasks.

Another intriguing and unexpected result in our study is the pattern of changes in the two variance components, VUCM and VORT, produced by the first dose of drug. This pattern included a drop in VORT and no change in VUCM, leading to an increase in the synergy index ΔV. In an earlier study evaluating the effects of dopamine-replacement drugs on indices of posture-stabilizing synergies (Falaki et al. 2017a), we also showed an increase in ΔV, although this was produced by a different pattern, namely an increase in VUCM without a significant change in VORT. The difference in the two patterns of change suggests a potential difference in the involved neural circuits from first dosage to chronic usage of medication in PD. Together, this is consistent with the idea that chronic and long-term exposure to dopamine replacement medications leads to major changes in brain circuitry, including changed sensitivity to drugs (Feigin et al. 2002; Hershey et al. 2003; Politis et al. 2017). Our findings of differential responses in VUCM and VORT to levodopa in the two PD populations bring a tantalizing possibility of using VORT and VUCM to gauge different basal ganglia circuity activity and the plasticity of responding to dopaminergic modulating treatment.

Analysis of variance vs. analysis of motor equivalence

One of the unexpected results of our study has been the lack of significant differences between the two groups and of the first medication dose in the outcome variables in the analysis of motor equivalence. Indeed, statistical considerations suggest that, assuming that the data are sampled from the same normal distribution, ME should be proportional to the square root from VUCM, and nME should be proportional to the square root from VUCM (Leone et al. 1961). Indeed, an earlier study of M-mode synergies stabilizing COP trajectory demonstrated similar effects of PD and of medication on the pairs of indices within analysis of variance and within the ME analysis (Falaki et al. 2017b).

There is, however, a potentially important difference between the cited earlier study by Falaki and colleagues (2017b) and the current study. The former study used a cyclical voluntary sway task and performed analysis across comparable phases in individual cycles. Since ongoing cyclical sway may be seen as a steady-state process, the assumption of sampling data from the same distribution likely was warranted. The current study, however, compared the data between two steady states separated by a quick action leading to a postural perturbation. It involved a corrective action by the subject and, hence, the data during SS1 and SS2 likely were sampled from different distributions. This could lead to loss of correlations between the variance indices and ME/nME indices as shown earlier (Cuadra et al. 2019).

The lack of significant effects on the ME and nME indices (although the trends were in the expected direction) shows that outcomes of analysis of motor equivalence should be considered as complementary, not redundant, to the analysis of inter-trial variance. Analysis of motor equivalence has obvious advantages such as high reliability of the outcome variables and relatively small number of trials, compared to the analysis of variance needed to reach a comparable criterion of reliability (Freitas et al. 2018; de Freitas et al. 2019). These factors make analysis of motor equivalence attractive for clinical studies, which typically involve subjects who may not be able to perform numerous trials.

Concluding comments

Analysis of motor synergies based on the UCM hypothesis becomes more and more broadly used in the field of neurological disorders (reviewed in Latash and Huang 2015; Vaz et al. 2019). Taken together, our previous study (de Freitas et al. 2020) and the current results suggest that synergy indices may serve as biomarkers for early-stage PD across tasks and sets of effectors, from multi-finger tasks to whole-body tasks. These are theory-based indices directly reflecting functioning in the motor domain, which may add specificity to non-motor screening tests in PD such as those based on sense of smell (Hummel 1999; Tissingh et al. 2001) and sleep structure (Howell and Schenck 2014) that currently are used.

We would like to acknowledge a few shortcomings of our study. The first and most obvious one is the relatively small number of subjects, which was primarily limited by the number of available dopamine-naïve patients with PD. This study and its counterpart (de Freitas et al. 2020) are only the first steps in understanding the effects of early-stage PD and dopamine-replacement medications on indices of performance-stabilizing synergies. The apparently contrasting effects of medication on the two variance components, VUCM and VORT, in our de novo group and in the earlier tested patients who had been on chronic medication treatment for months and years make it highly important to follow-up the current group and map the transition from one pattern of drug effects to the other pattern. Such a study could inform on changes in the neural circuitry produced by long-term drug exposure. Another limitation is performing analysis of multi-muscle synergies on the right side of the body only. Note that six of the patients with PD showed more symptoms on the right side of the body and five patients on the left side. On the other hand, our previous studies used similar protocols (Falaki et al. 2016, 2017a,b). In addition, another study (Park et al. 2012) showed similar effects of PD on synergy indices in both hands of patients at HY stage-I, which is characterized by PD symptoms on only one side of the body.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in the study. XH and MML were supported by NIH grants NS060722, ES019672, NS082151, and NS112008. MLL, XH, and MML were supported by NIH grant NS095873.

Footnotes

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest are claimed by any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Adler CH, Sethi KD, Hauser RA, Davis TL, Hammerstad JP, Bertoni J, … Ropinirole Study Group (1997) Ropinirole for the treatment of early Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 49: 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JL, McKay JL, Sawers A, Hackney ME, Ting lH (2017) Increased neuromuscular consistency in gait and balance after partnered, dance-based rehabilitation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurophysiol 118: 363–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au W-L, Lei N, Oishi MMK, McKeown MJ (2010) L-DOPA induced under-damped visually guided motor responses in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Brain Res 202: 553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazalgette D, Zattara M, Bathien N, Bouisset S, Rondot P (1986) Postural adjustments associated with rapid voluntary arm movements in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Adv Neurol 45: 371–374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman BD, Smucny J, Wylie KP, Shelton E, Kronberg E, Leehey M, Tregellas JR (2016) Levodopa modulates small-word architecture of functional brain networks in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 31:1676–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein NA (1947) On the Construction of Movements. Medgiz: Moscow: (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein NA (1967) The Co-ordination and Regulation of Movements. Pergamon Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Bleuse S, Cassim F, Blatt JL, Labyt E, Bourriez JL, Derambure P, Destée A, Defebvre L (2008) Anticipatory postural adjustments associated with arm movement in Parkinson’s disease: a biomechanical analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79: 881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloem BR, Grimbergen YA, van Dijk JG, Munneke M (2006) The “posture second” strategy: a review of wrong priorities in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 248: 196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet CT, Delval A, Defebvre L (2014) Interest of active posturography to detect age-related and early Parkinson’s disease-related impairments in mediolateral postural control. J Neurophysiol 112: 2638–2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Fan Y, Zhuang X, Feng D, Chen Y, Chan P, Du Y (2018) Postural sway in patients with early Parkinson’s disease performing cognitive tasks while standing. Neurol Res 40: 491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadra C, Falaki A, Sainburg RL, Sarlegna FR, Latash ML (2019) Case studies in neuroscience. The central and somatosensory contributions to finger inter-dependence and coordination: Lessons from a study of a “deafferented person”. J Neurophysiol 121: 2083–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danna-Dos-Santos A, Slomka K, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML (2007) Muscle modes and synergies during voluntary body sway. Exp Brain Res 179: 533–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Avella A, Saltiel P, Bizzi E (2003) Combinations of muscle synergies in the construction of a natural motor behavior. Nat Neurosci 6: 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Freitas PB, Freitas SMSF, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML (2018) Stability of steady hand force production explored across spaces and methods of analysis. Exp Brain Res 236: 1545–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Freitas PB, Freitas SMSF, Reschechtko S, Corson T, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML (2020) Synergic control of action in levodopa-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients: I. Multi-finger interaction and coordination. Exp Brain Res 238: 229–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener HC, Dichgans J, Guschlbauer B, Bacher M, Langenbach P (1989) Disturbances of motor preparation in basal ganglia and cerebellar disorders. Prog Brain Res 80: 481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falaki A, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML (2016) Impaired synergic control of posture in Parkinson’s patients without postural instability. Gait Posture 44: 209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falaki A, Huang X, Lewis MM, Latash ML (2017a) Dopaminergic modulation of multi-muscle synergies in postural tasks performed by patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 33: 20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falaki A, Huang X, Lewis MM, Latash ML (2017b) Motor equivalence and structure of variance: Multi-muscle postural synergies in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Brain Res 235: 2243–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigin A, Ghilardi MF, Fukuda M, Mentis MJ, Dhawan V, Barnes A, Ghez CP, Eidelberg D (2002) Effects of levodopa infusion on motor activation responses in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 59: 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas SMSF, de Freitas PB, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML (2019) Quantitative analysis of multi-element synergies stabilizing performance: Comparison of three methods with respect to their use in clinical studies. Exp Brain Res 237: 453–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenklach A, Louie S, Koop MM, Bronte-Stewart H (2009) Excessive postural sway and the risk of falls at different stages of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 24: 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, and Black WC (1995) Factor analysis In: Borkowski D (Ed.) Multivariate data analysis, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, p. 364–404. [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorff JM (2007) Gait dynamics, fractals and falls: finding meaning in the stride-to-stride fluctuations of human walking. Hum Mov Sci 26: 555–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey T, Black KJ, Carl JL, McGee-Minnich L, Snyder AZ, Perlmutter JS (2003) Long term treatment and disease severity change brain responses to levodopa in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74: 844–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn M, Yahr M (1967) Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 17: 427–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell MJ, Schenck CH (2015) Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and neurodegenerative disease. JAMA Neurol 72: 707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T (1999) Olfactory evoked potentials as a tool to measure progression of Parkinson’s disease In: Chase TN, Bedard P Focus on Medicine Vol 14 - New developments in the drug therapy of Parkinson’s disease, p. 47–53. Oxford: Blackwell Science. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenko YP, Poppele RE, Lacquaniti F (2004) Five basic muscle activation patterns account for muscle activity during human locomotion. J Physiol 556: 267–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenko YP, Dominici N, Lacquaniti F (2007) Development of independent walking in toddlers. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 35: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo HJ, Lucassen E, Huang X, Latash ML (2017) Changes in multi-digit synergies and their feed-forward adjustments in multiple sclerosis. J Motor Behav 49: 218–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klous M, Mikulic P, Latash ML (2011) Two aspects of feed-forward postural control: Anticipatory postural adjustments and anticipatory synergy adjustments. J Neurophysiol 105: 2275–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy V, Goodman SR, Latash ML, Zatsiorsky VM (2003a) Muscle synergies during shifts of the center of pressure by standing persons: Identification of muscle modes. Biol Cybern 89: 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy V, Latash ML, Scholz JP, Zatsiorsky VM (2003b) Muscle synergies during shifts of the center of pressure by standing persons. Exp Brain Res 152: 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Huang X (2015) Neural control of movement stability: Lessons from studies of neurological patients. Neurosci 301: 39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Aruin AS, Neyman I, Nicholas JJ (1995) Anticipatory postural adjustments during self-inflicted and predictable perturbations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat 58: 326–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Levin MF, Scholz JP, Schöner G (2010) Motor control theories and their applications. Medicina 46: 382–392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone FC, Nottingham RB, Nelson LS (1961) The folded normal distribution. Technometrics 3: 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- McKay JL, Goldstein FC, Sommerfeld B, Bernhard D, Parra SP, Factor SA (2019) Freezing of gait can persist after an acute levodopa challenge in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinson Dis 5: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M, Zampieri C, Carlson-Kuhta P, Chiari L, Horak FB (2009) Anticipatory postural adjustments prior to step initiation are hypometric in untreated Parkinson’s disease: an accelerometer-based approach. Eur J Neurol 16: 1028–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M, Carlson-Kuhta P, Zampieri C, Nutt JG, Chiari L, Horak FB (2012) Postural sway as a marker of progression in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot longitudinal study. Gait Posture 36: 471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massion J (1992) Movement, posture and equilibrium – interaction and coordination. Prog Neurobiol 38: 35–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden CD, Parkes JD (1977) Success and problems of long-term levodopa therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 309: 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattos DJ, Latash ML, Park E, Kuhl J, Scholz JP (2011) Unpredictable elbow joint perturbation during reaching results in multijoint motor equivalence. J Neurophysiol 106:1424–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattos D, Kuhl J, Scholz JP, Latash ML (2013) Motor equivalence (ME) during reaching: Is ME observable at the muscle level? Motor Control 17:145–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merello M, Gerschcovich ER, Ballesteros D, Cerquetti D (2011) Correlation between the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease rating scale (MDS-UPDRS) and the Unified Parkinson’s Disease rating scale (UPDRS) during L-dopa acute challenge. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 17: 705–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozinga SJ, Machado AG, Miller Koop M, Rosenfeldt AB, Alberts JL (2015) Objective assessment of postural stability in Parkinson’s disease using mobile technology. Mov Disord 30: 1214–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SJ, Eigenraam L, Hoque T, McCaig RG, Troiano A, McKeown MJ (2009) Levodopa-sensitive, dynamic changes in effective connectivity during simultaneous movements in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci 158: 693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Wu Y-H, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML (2012) Changes in multi-finger interaction and coordination in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurophysiol 108: 915–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML (2014) Dopaminergic modulation of motor coordination in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Rel Disord 20: 64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieruccini-Faria F, Vitório R, Almeida QJ, Silveira CR, Caetano MJ, Stella F, Gobbi S, Gobbi LT (2013) Evaluating the acute contributions of dopaminergic replacement to gait with obstacles in Parkinson’s disease. J Mot Behav 45: 369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politis M, Wilson H, Wu K, Brooks DJ, Piccini P (2017) Chronic exposure to dopamine agonists affects the integrity of striatal D2 receptors in Parkinson’s patients. Neuroimage Clin 16: 455–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez KL, Roemmich RT, Cam B, Fregly BJ, Hass CJ (2013) Persons with Parkinson’s disease exhibit decreased neuromuscular complexity during gait. Clin Neurophysiol 124: 1390–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schade S, Sixel-Döring F, Ebentheuer J, Schulz X, Trenkwalder C, Mollenhauer B (2017) Acute levodopa challenge test in patients with de novo Parkinson’s disease: Data from the DeNoPa cohort. Mov Disord Clin Pract 4: 755–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Schoner G (1999) The uncontrolled manifold concept: identifying control variables for a functional task. Exp Brain Res 126:289–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulders K, Dale ML, Carlson-Kuhta P, Nutt JG, Horak FB (2016) Pharmacological treatment in Parkinson’s disease: Effects on gait. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 31: 3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnik S, Pazin N, Coelho C, Rosenbaum DA, Scholz JP, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML (2013) End-state comfort and joint configuration variance during reaching. Exp Brain Res 225: 431–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo WP, Rodrigues JP, Mastaglia FL, Thickbroom GW (2013) Comparing kinematic changes between a finger-tapping task and unconstrained finger flexion-extension task in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Exp Brain Res 227: 323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting LH, Macpherson JM (2005) A limited set of muscle synergies for force control during a postural task. J Neurophysiol 93: 609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissingh G, Berendse HW, Bergmans P, DeWaard R, Drukarch B, Stoof JC, Wolters EC (2001) Loss of olfaction in de novo and treated Parkinson’s disease: possible implications for early diagnosis. Mov Disord 16: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenkwalder C, Kies B, Rudzinska M, Fine J, Nikl J, Honczarenko K, … Kassubek J (2011). Rotigotine effects on early morning motor function and sleep in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study (RECOVER). Mov Disord 26: 90–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresch MC, Jarc A (2009) The case for and against muscle synergies. Curr Opin Neurobiol 19: 601–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresch MC, Cheung VC, d’Avella A (2006) Matrix factorization algorithms for the identification of muscle synergies: evaluation on simulated and experimental data sets. J Neurophysiol 95: 2199–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Criekinge T, Vermeulen J, Wagemans K, Schröder J, Embrechts E, Truijen S, Hallemans A, Saeys W (2019) Lower limb muscle synergies during walking after stroke: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 23:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz DA, Pinto VA, Junior RRS, Mattos DJS, Mitra S (2019) Coordination in adults with neurological impairment – A systematic review of uncontrolled manifold studies. Gait Posture 69: 66–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viitasalo MK, Kampman V, Sotaniemi KA, Leppavuori S, Myttyla VV, Korpelainen JT (2002) Analysis of sway in Parkinson’s disease using a new inclinometry-based method. Move Disord 17: 663–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Watanabe K, Asaka T (2017) Aging effect on muscle synergies in stepping forth during a forward perturbation. Eur J Appl Physiol 117: 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter DA, Prince F, Frank JS, Powell C, Zabjek KF (1996) Unified theory regarding A/P and M/L balance in quiet stance. J Neurophysiol 75: 2334–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman CD, Thrasher TA (2019) The influence of dopaminergic medication on balance automaticity in Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture 70: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatsiorsky VM, Duarte M (1999) Instant equilibrium point and its migration in standing tasks: rambling and trembling components of the stabilogram. Motor Control 3: 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]