Highlights

-

•

It is a case study of an immunocompromised patients affected by Mucormycosis which is - a profoundly mortal fungal infection.

-

•

In order to restore the function, enhance the cosmetic appearance and quality of life of the patient, surgical intervention is often necessary to correct the various pathologies affecting the patients.

-

•

This paper highlights the significance of prompt diagnosis and urgent treatment, especially among high-risk patients, of this potentially lethal phenomenon and the surgical procedure undertaken to remove the disease afecting the person and improve the patient's overall health.

-

•

The management of our patient demonstrates the need for an early visual identification and diagnosis approach that is multidisciplinary, multi-factorial and multi-faceted.

Keywords: Mucormycosis, Amphotericin B(AmB), Rhizopus, Diabetes mellitus, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Mucormycosis is a rare, rapidly progressive and a fulminant, life-threatening, opportunistic infection. Although it most commonly manifests in diabetic patients, its presence in other immunologically compromised patients cannot be ruled out. Its etiology is saprophytic fungal organisms, with rhizopus being the most common causative organism. Clinically the disease is marked by a partial loss of neurological function and a progressive necrosis due to the invasion of the organisms into the blood vessels causing a lack of blood supply. The disease may progress to involve the cranium thereby increasing the mortality rate. The first line of management in mucormycosis is antifungal therapy which may extend and also include surgical management.

Presentation of case

Authors present here two patients with mucormycosis affecting the maxillofacial region, that were treated by including both medical and surgical lines of management.

Discussion

This report aims to highlight the importance of prompt diagnosis and urgent management of this potentially fatal phenomenon, particularly among high-risk individuals.

Conclusion

This case report intensifies the importance of considering mucormycosis as a possible diagnosis in spontaneous necrotic soft tissue lesions of the face, especially in an immunocompromised patient.

1. Introduction

Mucormycosis is an invasive fungal infection caused by fungi of the order of Mucorales [1]. It was first described by Paltauf in 1885 [2]. It is the third most common opportunistic fungal infection after candidiasis and aspergillosis [4]. Rhizopus, along with Mucor and Lichtheimia account for about 70–80% of all the cases of mucormycosis [[5], [6], [7]]. These saprophytic organisms exist in the soil, manure, fruits, starchy foods and are frequently found to colonize the oral mucosa, the nasal mucosa, the paranasal sinuses and the pharyngeal mucosa of asymptomatic patients [1,10]. Based on anatomic localization mucormycosis can be categorized as follows [[11], [12], [13], [14]]:

The authors hereby report two cases of patients with mucormycosis affecting the maxillofacial region, that were treated by both medical and surgical line of management. This report aims to highlight the importance of prompt diagnosis and urgent management of this potentially fatal phenomenon, particularly amongst high-risk individuals. The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [21].

2. Case report

2.1. Case 1

A 60 yr old male presented to our institute with a painful non-healing wound, involving the palate since the last four months. He also complained of pus discharge and bad breath along with difficulty in eating, drinking and swallowing. There was also a complaint of incomplete healing of the sockets of maxillary anterior teeth, post extraction. He was a known diabetic since 6 years. Intra oral examination revealed unhealed sockets in the maxillary anterior region with exposed necrotic bone. A necrotizing ulcer was also seen involving the alveolar bone of the anterior maxillary region and the entire hard palate. The ulcer was approximately 5 × 5 cm in size and was covered by a yellowish slough (Fig. 1). Palpation revealed that the whole of the maxillary arch was mobile. The lymph nodes were not palpable. The clinical picture was suggestive of a deep seated fungal infection.

Fig. 1.

Unhealed sockets in maxillary anterior region and exposed necrotic maxillary bone and palatal area with a necrotizing ulcer.

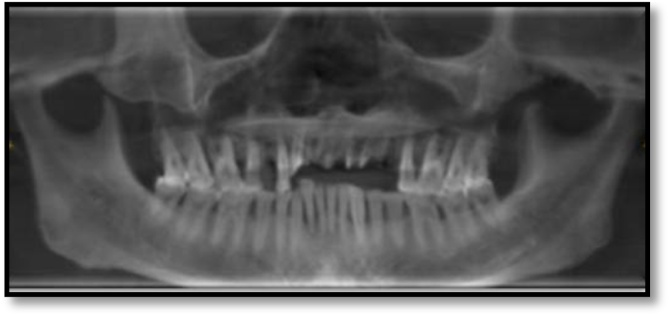

Hematological investigations revealed, a high fasting blood sugar level, decreased hemoglobin (8 g%), and HbA1c at 8.7 %. Radiographic examination by means of an Orhtopantomogram(OPG) and Cone-beam computed tomography examination(CBCT) revealed discontinuity in the nasal and maxillary areas with moth-eaten appearance of bone accompanied with haziness and obliteration of both the maxillary sinuses, Osteolytic lesions were also observed involving the maxillary alveolar bone that were extending from right maxillary second molar to left maxillary first molar region. Perforation of the palate was also evident (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Cytological smear and incisional biopsy were taken from alveolar and palatal regions to further confirm the diagnosis.

Fig. 2.

OPG showing discontinuity in rhinomaxillary area.

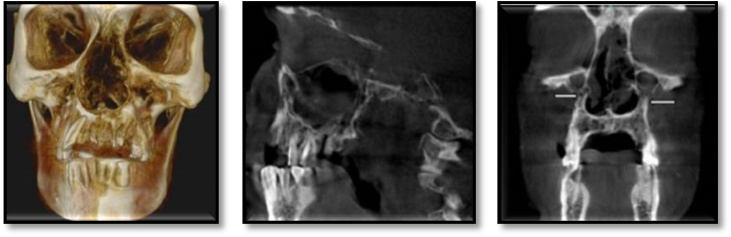

Fig. 3.

CBCT revealed erosion of the maxillary bone with moth eaten appearance, palatal perforation, discontinuity in maxillary sinus walls bilaterally involving nasal concha and septum, bilateral obliteration of maxillary sinus.

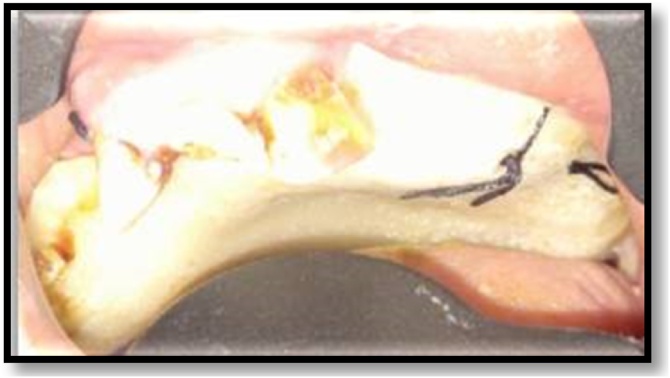

Based on clinical, radiological, and histopathological findings, the final diagnosis of rhinomaxillary mucormycosis was made. The patient was referred to the physician for the control of diabetes and to improve the hemoglobin. Simultaneously, systemic antifungal therapy (IV Amphotericin B) was administered to the him. After the control of diabetes, surgical excision of the maxilla was done along with debridement of the nasal vault. An obturator was given to cover the defect (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). The histopathology of the excised specimen confirmed our diagnosis of mucormycosis. The patient was closely followed up and the healing was uneventful (Fig. 6).’

Fig. 4.

Surgical debridement.

Fig. 5.

Maxillary obturator.

Fig. 6.

Postoperative healing.

2.2. Case 2

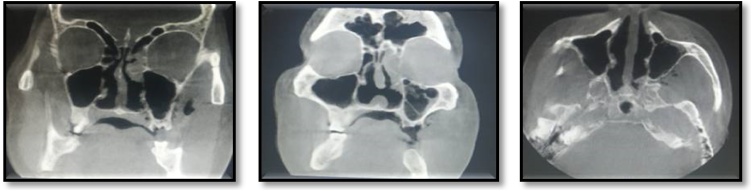

A 67-year male reported to our institute with a complaint of mild pain, exposed bone, and pus discharge from the left quadrant of the upper jaw with a duration of 1 month. He is a known diabetic for the past 10 years. He gave a history of extraction of his tooth himself. On intra-oral examination, a grayish-colored bone, denuded of its mucoperiosteum, was seen on the left side of the maxillary alveolus, extending to involve the hard palate (Fig. 7). This dentoalveolar segment was mobile. A Computed Tomography scan revealed a thickening of the maxillary sinus lining (Fig. 8). Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of mucormycosis. So, Sequestrectomy and debridement of the affected bone were done. Antifungal therapy was administered in the form of Lipid complex Amphotericin B, 250 mg IV 12 hourly for 3 weeks, that was slowly infused over 4–6 h. The patient’s blood glucose levels were closely monitored. Post operatively the patient's condition improved significantly. An obturator was fabricated by the prosthodontist to cover the palatal defect (Fig. 9). A post operative follow-up after 2 months revealed satisfactory healing and there was no clinical evidence of mucormycosis. The general status of the patient also improved and vital signs were within normal limits.

Fig. 7.

Exposed necrotic bone in left maxilla.

Fig. 8.

CBCT revealed thickening of maxillary sinus lining.

Fig. 9.

Post operative palatal obturator.

3. Discussion

Mucormycosis has already been established as the most rapidly progressive and lethal form of fungal infection found in humans. It can be precipitated because of trauma, dental extractions, intramuscular injections to infected wounds, insect bite, intravenous drug abuse, prosthetic devices, etc [1,4,8,10].

3.1. Etiology

It usually manifests in metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus with ketoacidosis, chronic renal insufficiency, hematologic malignancy, organ transplant, malnutrition, increased serum iron, prolonged neutropenia, or by immunosuppressive drugs such as steroids, cytotoxics, and broad-spectrum antibiotics, deferoxamine therapy, etc [1,10].

In approx. 50 % of mucormycosis patients, diabetes mellitus serves as a predisposing factor due to the pronounced availability of glucose, lower pH and impaired host defense mechanism [1,[17], [18], [19]].

Deferoxamine may be associated with a tense form of mucormycosis as it can cause inhibition of Iron-catalyzed peroxidase production of free radicals (that is important for killing fungi). Increased serum iron intensifies mucormycosis as it holds a siderophoric affinity to the fungus. The iron bound to siderophores (an iron-binding compound secreted by microorganisms) can be used by the fungi, whereas that bound to transferrin cannot be used [17].

3.2. Pathophysiology

In humans, the infection is thought to be caused by asexual spore formation. The tiny spores then become airborne and land on the oral and nasal mucosa of humans. In immunocompetent hosts, these spores will be contained by a phagocytic response. If this fails, germination will occur and hyphae will develop. As the polymorphonuclear leukocytes are less effective in removing hyphae, the infection then becomes established. The fungus shows a remarkable affinity for arteries, veins and lymphatics. It invades the vessel wall producing extensive endothelial damage, thrombosis, and infarction resulting in progressive tissue ischemia and necrosis of deep tissues, including muscle and fat. This eventually results in sepsis and multiorgan failure [9].

3.3. Clinical features

Facial Pain and swelling precedes oral ulceration, that progresses to produce necrotic eschars in nasal turbinate's and palate with Resulting denudation or osteomyelitis of the underlying facial bone. Necrotic lesions signify aggressive angioinvasive infections [3,4,8].

Infection from paranasal sinuses can easily spread to the mouth, causing palatal perforation or to the orbit through the nasolacrimal duct and medial orbit. Spread towards the brain may occur through the orbital apex or through vessels, or cribriform plate. As the disease progresses towards the orbit and skull, the patient may suffer from either orbital cellulitis, chemosis, proptosis, loss of vision, ophthalmoplegia, superior orbital fissure syndrome, sagittal sinus thrombosis, epidural or subdural abscess formation [1,4,16,18].

A bloody discharge from the nose may serve as the first sign that infection has invaded through the turbinate's into the brain. Extension into the cavernous sinus and involvement of the internal carotid artery may result in cerebral ischemia, brain infarction, and ultimately death [4,17,20].

3.4. Investigation

Plain orbit or sinus radiography- Not reliable

Computed Tomography (CT)- A sensitive indicator of the extent of orbital and cranial involvement. Shows opacification of the paranasal sinuses, thickening of the sinus mucosa, and bone destruction without an air-fluid level. Soft tissue swelling, proptosis, and swelling of the extra ocular muscles can also be seen [10].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)- T2-weighted MR images may demonstrate intracerebral extension while contrast-enhanced MRI scans may demonstrate the perineural spread of disease. Due to the aggressive nature of mucormycosis CT or MRI scans should be obtained at frequent intervals to monitor disease extension and response to therapy [20].

Angiography Or Surgical Exploration - Used in areas of anatomic complexity, like orbit, where reactive inflammation may be difficult to distinguish from true invasion with computed tomography or MRI [20].

3.5. Histopathological examination

Pathologic examination on permanent sections with H&E, PAS, or specialized fungal stains like Grocott methenamine-silver is considered as - the gold standard for diagnosing mucormycosis, but this process can be lengthy and time-consuming hence it may cause a delay in appropriate treatment, thus increasing morbidity and mortality [17].

In order to obtain an earlier diagnosis, frozen sections are recommended while doing diagnostic biopsy. Intraoperative negative margins with frozen sections helps the surgeon to determine the extent of the diseased margin [20].

One should remember that sometimes surface swab specimen can be negative for mucormycosis as it tends to invade deeply into the tissues. Specimen may include skin scrapings, nasal discharge, aspirates from the sinuses, needle biopsies, or tissue sections [15].

3.6. Treatment

The early initiation of treatment after diagnosis is crucial for a successful outcome in treating mucormycosis. First, the underlying medical condition that makes the patient susceptible to infection, must be corrected. This includes blood glucose control, tapering of steroids, and reducing or stopping any immunosuppressive medications. As the main initiator of the disease is neutropenia; a CBC should be obtained with emphasis on the neutrophil count. Monitoring iron levels is required as the fungus depends on its availability (high ferritin levels and low total iron-binding capacity are indicative of the organism’s virulence). Next, systemic antifungal therapy should be initiated. The agent of choice is AmB. This polyene agent binds to sterols and forms trans-membrane channels; consequently forming pores that disrupt the fungal cell wall synthesis. Finally, surgical debridement of diseased tissue is essential for the successful management of a disease [10,16].

Conventional AmB (1–1.5 mg/kg/d IV) can be used, but the dose should be temporarily reduced when serum urea nitrogen level exceeds 40 mg/100 mL or serum creatinine level exceeds 3.0 mg/100 mL. conventional AmB is associated with more toxic effects like nephrotoxicity so lipid preparations of AmB (liposomal AmB) are used which appear to be less toxic and provide the same therapeutic effect. Liposomal AmB increases circulation time and alters the biodistribution of the AmB, so they are able to localize and reach in greater concentrations in infected and inflamed tissues. Further, a 50 % lethal dose of liposomal AmB is approx. 10–15 times higher than that of conventional AmB. The recommended dose of liposomal AmB is 3−5 mg/kg/d prepared as a 1 mg/mL infusion and delivered at a rate of 2.5 mg/kg/hour. Salvage posaconazole therapy (800 mg daily, split between two or four doses, orally administered) for refractory mucormycosis has also been reported [15,17,20].

Debridement helps to prevent the systemic spread of infection by facilitating removal of the diseased tissue harboring infectious fungal elements and has to be repeated based on disease progression. In some cases, radical resection may be required, which can include partial or total maxillectomy, mandibulectomy, and orbital exenteration.5 Surgical debridement usually proceeds quickly because of an almost bloodless field.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy aids neovascularization, promoting healing in poorly perfused acidotic and hypoxic but viable areas of tissue. It should consist of exposure to 100 % oxygen for 90 min at pressures from 2.0 to 2.5 atm with 1 or 2 exposures daily, for a total of 40 treatments. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy may prove to be effective in patients who appear to be deteriorating despite optimal medical and surgical therapies.

Other therapies may include nebulized/local irrigation with AmB, topical hydrogen peroxide, leukocyte transfusions, treatment with interferon-gamma, the use of GM-CSF, G-CSF, or polyvalent immunoglobulin, and the combination of AmB with flucytosine, rifampin, or fluconazole [3].

According to some case series of patients with mucormycosis of the maxillofacial region, the mortality rate with medical treatment alone was 70 % whereas it is approx. 14 % in those treated both medically and surgically [3,18].

4. Conclusion

Because of the extremely aggressive nature, mucormycosis may assume the presentation of malignancy, syphilis, tuberculosis, midline lethal granuloma syndrome, Wegener granulomatosis, aspergillosis, and other systemic mycoses. So distinction must be made between these lesions.

These case reports highlight the importance of considering mucormycosis as a possible diagnosis in spontaneous necrotic soft tissue lesions of the face especially in an immunocompromised patient. The prognosis is usually poor, influenced by time taken for diagnosis and most importantly by the patient’s systemic status. However, with early diagnosis and aggressive treatment, prognosis can be improved in order to increase patient’s survival rate.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is exempted by the institution.

Consent

"Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request".

Author contribution

Contributor 1: Concepts, Design, Definition of Intellectual Content, Literature Search, Clinical Study, Experimental Study, Data Acquisition, Data Analysis, Statistical Analysis, Manuscript preparation, Manuscript editing, Manuscript review, Guarantor.

Contributor 2: Concepts, Design, Definition of Intellectual Content, Literature Search, Clinical Study, Experimental Study, Data Acquisition, Data Analysis, Statistical Analysis, Manuscript preparation, Manuscript editing, Manuscript review, Guarantor.

Contributor 3: Concepts, Design, Definition of Intellectual Content, Literature Search, Clinical Study, Experimental Study, Data Acquisition, Data Analysis, Statistical Analysis, Manuscript preparation, Manuscript editing, Manuscript review, Guarantor.

Contributor 4: Concepts, Definition of Intellectual Content, Literature Search, Clinical Study, Data Acquisition, Statistical Analysis, Manuscript preparation, Manuscript review.

Contributor 5: Concepts, Definition of Intellectual Content, Clinical Study, Experimental Study, Data Analysis, Statistical Analysis, Manuscript preparation, Manuscript review, Guarantor.

Contributor 6: Concepts, Design, Definition of Intellectual Content, Data Acquisition, Statistical Analysis, Manuscript preparation, Manuscript review, Guarantor.

Registration of research studies

Not a clinical trial, it’s a case report.

Guarantor

Dr. Kainat Khan.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Barrak H. Hard palate perforation due to mucormycosis: report of four cases. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2007;121(11):1099–1102. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107006354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paltauf A. Mycosis mucorina. Virchows Arch. Pathol. Anat. 1885;102:543. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen A., Shoukair F., Korem M., Shaulov A., Casap N. Successful mandibular mucormycosis treatment in the severely neutropenic patient. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019;77(6):1209. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2019.02.012. e1-1209.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagare J., Johaley S. Diagnostic role of CBCT in fulminating mucormycosis of maxilla. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2019;6(7):575–579. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez E. Spectrum of Zygomycetes species identified in clinically significant specimens in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:1650–1656. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00036-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roden M.M. Epidemiology and outcome of mucormycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;41:634–653. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rüping M.J. Forty-one recent cases of invasive zygomycosis from a global clinical registry. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:296–302. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gholinejad Ghadi N., Seifi Z., Shokohi T., Aghili S., Nikkhah M., Vahedi Larijani L. Fulminant mucormycosis of maxillary sinuses after dental extraction inpatients with uncontrolled diabetic: two case reports. J. Mycol. Méd. 2018;28(2):399–402. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribeiro N., Cousin G., Wilson G., Butterworth D., Woodwards R. Lethal invasive mucormycosis: case report and recommendations for treatment. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001;30(2):156–159. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2000.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fattah S., Hariri F., Ngui R., Husman S. Tongue necrosis secondary to mucormycosis in a diabetic patient: a first case report in Malaysia. J. Mycol. Med. 2018;28(3):519–522. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spellberg B., Edwards J.J., Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:556–569. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.556-569.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribes J.A., Vanover-Sams C.L., Baker D.J. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000;13:236–301. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.236-301.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis R.E., Kontoyiannis D.P. Epidemiology and treatment of mucormycosis. Future Microbe. 2013;8:1163–1175. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrikkos G., Skiada A., Lortholary O., Roilides E., Walsh T.J., Kontoyiannis D.P. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:S23–S34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leitner C., Hoffmann J., Zerfowski M., Reinert S. Mucormycosis: necrotizing soft tissue lesion of the face. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003;61(11):1354–1358. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McSpadden R., Martin J., Mehrotra S., Thorpe E. Mucormycosis causing Ludwig Angina: a unique presentation. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017;75(4):759–762. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metzen D. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2012;40:e321–e327. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar J., Babu P., Prabu K., Kumar P. Mucormycosis in maxilla: rehabilitation of facial defects using interim removable prostheses: a clinical case report. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2013;5(6):163. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.114322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prabhu S. A fatal case of rhinocerebral mucormycosis of the jaw after dental extractions and review of literature. J. Infect. Publ. Health. 2017;11(3):301–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prasad K., Lalitha R., Reddy E., Ranganath K., Srinivas D., Singh J. Role of early diagnosis and multimodal treatment in rhinocerebral mucormycosis: experience of 4 cases. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012;70(2):354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]