Abstract

Background:

The cost of diabetes medications and supplies is rising, resulting in access challenges. This study assessed the prevalence of and factors predicting underground exchange activities—donating, trading, borrowing, and purchasing diabetes medications and supplies.

Research Design and Methods:

A convenience sample of people affected by diabetes was recruited online to complete a survey. Mixed method analysis was undertaken, including logistic regression to examine the relationship between self-reported difficulty purchasing diabetes medications and supplies and engagement in underground exchange activity. Thematic qualitative analysis was used to examine open-text responses.

Results:

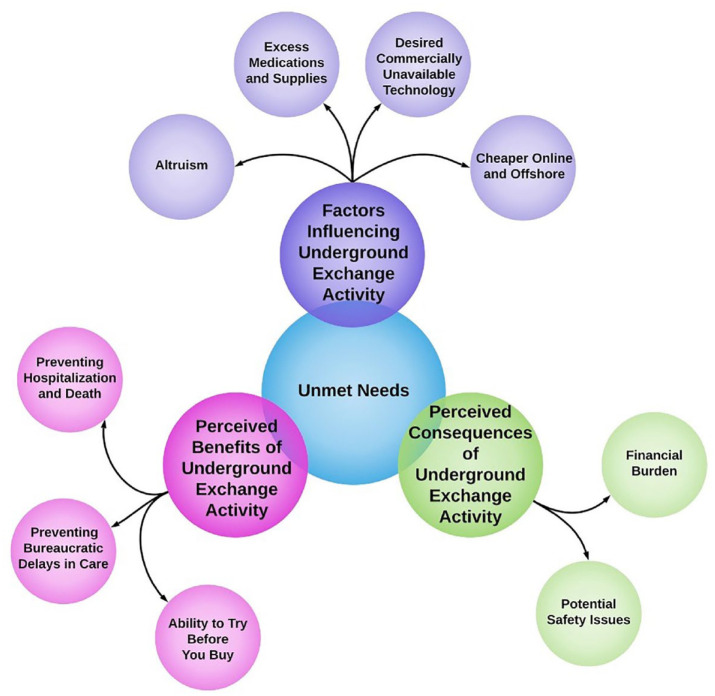

Participants (N = 159) self-reported engagement in underground exchange activities, including donating (56.6%), donation receiving (34.6%), trading (23.9%), purchasing (15.1%), and borrowing (22%). Such activity took place among a variety of individuals, including friends, family, coworkers, online acquaintances and strangers. Diabetes-specific financial stress predicted engagement in trading diabetes mediations or supplies (OR 6.3, 95% CI 2.2-18.5) and receiving donated medications or supplies (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.1-7.2). One overarching theme, unmet needs, and three subthemes emerged: (1) factors influencing underground exchange activity, (2) perceived benefits of underground exchange activity, and (3) perceived consequences of underground exchange activity.

Conclusion:

Over half of the participants in this study engaged in underground exchange activities out of necessity. Providers must be aware about this underground exchange and inquire about safety and possible alternative resources. There is an urgent need to improve access to medications that are essential for life. Our study points to a failure in the US healthcare system since such underground exchanges may not be necessary if medications and supplies were accessible.

Keywords: diabetes, social media, insulin, cost of illness, health services accessibility, diabetes technology

Introduction

The price of insulin per unit has doubled between 2012 and 2016, translating to $15 per day for the average insulin user.1 Insulin price increases have placed significant financial burden on individuals and families affected by diabetes.2 In 2017, 28.5 million, 8.8% of the population, was without health insurance in the United States,3 limiting access. Many insurance companies limit how much medication or diabetes supplies an individual may receive, despite prescription from their prescribing provider, and increasing deductibles have further strained families that have health insurance. As a result, access to diabetes medications and supplies has decreased.

People with diabetes (PWD) who are unable to access diabetes medications, such as insulin, even for short intervals, are at higher risk for diabetes-related complications, diabetic ketoacidosis, and even death. A recent report indicates one in four PWD ration insulin due to cost.4 There has been a rise in media reports focused on the cost of diabetes management and the toll it has on individuals and families.5 Recently, the media has highlighted PWD engaging in a “black market” for insulin as a result of the rising costs to manage diabetes.6 Such activity includes donating, trading, purchasing, and borrowing.

Diabetes is not the first condition for which a black market was created to support health. In the 1980s, when experimental HIV treatment was inaccessible to many, an underground exchange for treatment was developed coined “Dallas Buyers Club.”7 Since then, “buyers clubs” have been viewed as a universal strategy for those who cannot afford the treatment of chronic conditions.8 “Right to Try” laws have been enacted in some states allowing patients who are close to death the ability to access off-label medications.9 Historically, buyers clubs and the Right to Try laws have been based on experimental treatments for HIV, hepatitis, and cancer and not for the treatment of diabetes. Many diabetes medications and supplies have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for decades (eg, insulin and glucose strips), yet, they remain inaccessible for many.

Given anecdotal reports of underground exchange to diabetes medications and supplies, and the lack of research in this area, evidence of PWD engagement in underground exchange is necessary to better understand the access issue. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to (1) describe the real-world phenomenon of individuals and families affected by diabetes who engage in underground exchange activity and (2) examine any positive or negative safety implications related to underground exchange activity.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a mixed methods study that includes an exploratory cross-sectional design of a convenience sample of diabetes online community (DOC) users. The DOC is a user-generated term that encompasses people affected by diabetes who engage in online activities (such as community forums, video/podcasts, and social media websites) to share experiences and support in siloed or networked platforms.10,11 Surveys were collected between January and April of 2019.

Sample, Setting, and Recruitment

Diabetes online community users were provided with a brief announcement of the study on Facebook (four recruitment posts on one of the author’s profile page, one post to a private diabetes group based in Utah, and two posts by diabetes advocates), one blog post written by one author on her community blog, and Twitter (six original recruitment posts on one of the author’s profile page tagging #diabetes, #insulin4all, #dsma, and/or #doc). All posts were generated within a two-week period. Those interested in the study clicked on a link that further described the study within an online REDCap12 survey. Participants were included if they were DOC users living with diabetes or directly cared for someone living with diabetes (i.e. parent, spouse). Participants were excluded if they were unable to read and write English. Participants did not receive any incentive for their participation in this study.

Data Collection

Given the lack of evidence on diabetes-related underground exchange activity, the authors came to a consensus on what quantitative and qualitative questions participants should be asked. Participants were asked to undergo a 88-question survey examining demographics, personal health history, family health history, diabetes financial strain, financial distress using the eight-item InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Wellbeing scale,13 and engagement in underground exchange activity (donating, trading, borrowing, and purchasing from a nonauthorized provider). Donation is described as either donors (donate diabetes medications and/or supplies to others) or donation receivers (received medications and/or supplies from another person). Trading occurs when there is an exchange of items between two people. Purchasing is defined as an exchange of money for the purpose of buying diabetes medications and/or supplies from a nonauthorized supplier. Borrowing is defined as a short-term use of a diabetes medication and/or supplier that is returned. Up to an additional 69 questions were asked if participants indicated they were engaged in underground exchange activity to better understand who they engaged with, why and when this took place, and what medications and supplies were involved using both categorical and open text variables. Between the two sets of questions, 26 elaborative open-ended questions were asked, as well as eight story-based open-ended questions. Measures are further described in Table 1 and a listing of all questions is provided in the supplemental material. The study was piloted with four individuals living with diabetes to guide survey development and address usability. This study focuses exclusively on underground exchange activity.

Table 1.

Data Collection Measures.

| Measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Demographics | Questions focused on age, gender identity, race, ethnicity, marital status, education, income, number of people financially supported living in the home, and the country the participant resides in |

| Personal health history | Questions focused on diabetes type and duration, self-reported most recent A1C level, health insurance status, dollars spent on diabetes medications and supplies each month, dollars spent on all household-related health expenses each month, types of medications used to manage diabetes, insulin pump and continuous glucose monitoring device usage, and presence of diabetes-related complications |

| Family health history | Presence of other family members with diabetes or other health conditions that require financial support |

| Diabetes financial strain | Difficulty affording diabetes medications and supplies, discussions with healthcare providers about inability to pay for diabetes mediations and supplies, experience receiving medication or supply samples, request for patient assistance, relationship with family due to the cost of diabetes management, engagement with underground exchange activities (donation, trading, purchasing, or loaning diabetes medications and supplies), glucose check or medication rationing, experience with nonmedical switch, inability to use diabetes technology due to cost, fundraising, healthcare provider prescribing |

| IFDFW scale | Validated eight-item scale measuring general financial distress and wellbeing using a ten-point Likert response13,14 that has been used in the evaluation of financial hardships in cancer15 |

| Up to an additional 69 questions based on engagement in donating, trading, borrowing, or buying diabetes medications and/or supplies from a nonauthorized provider within the past 12 months | |

| Engagement in underground exchange activity | Relationship with whom the underground exchange activity took place, the frequency of and rationale for underground exchange activity, and the medications/supplies involved in the underground exchange activity |

Abbreviation: IFDFW, InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Wellbeing.

Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM, United States) version 26.0. The primary goal was to examine the relationship, using binary logistic regression, between self-report of difficulty purchasing diabetes medications and supplies (coded yes/no) and engagement in underground exchange activity (donating, trading, borrowing, and purchasing from a nonauthorized provider).

The secondary goal was to examine the open-ended responses using qualitative analysis. First, the data were extracted into an excel file based on responses to each question. Coders conducted an initial reading of the data set and noted initial impressions. Second, a codebook was developed and revised through the ongoing discussions among the study team using excel.14 Third, the corpus of data was applied to the codebook.14,15 Finally, the research team employed inductive thematic analysis to identify emergent themes.16 Saturation was determined by examining data content, not code frequency.17 All members of the study team reviewed the data and came to an agreement on the emergent themes presented.

Results

Participants (N = 159) included 106 adult PWD and 40 care partners and caregivers (13 participants did not identify their relationship to diabetes). The average age was 42 years with most participants being female, white, college-educated, and insured with various levels of income. See Table 2 for additional participant characteristics.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Participants (N = 159) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.8 (11.8); range 20-72 |

| Diagnosis (duration in years) mean (SD) | 23.8 (13.6) Adults; 6.5 (4.2) Children (parent reported) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 34 (22.5) |

| Female | 117 (77.5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (0.7) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 145 (99.3) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 (1.3) |

| Asian | 2 (1.3) |

| African American | 3 (1.9) |

| White | 145 (91.2) |

| Country, n (%) | |

| United States | 136 (94.4) |

| Not United States | 8 (5.6) |

| Income, n (%) | |

| Less than $25 000 | 12 (7.9) |

| $25 000-$34 999 | 8 (5.3) |

| $35 000-$49 999 | 11 (7.3) |

| $50 000-$74 999 | 22 (14.6) |

| $75 000-$99 999 | 31 (20.5) |

| $100 000-$149 999 | 25 (16.6) |

| More than $150 000 | 25 (16.6) |

| Prefer not to say | 17 (11.3) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Some high school | 2 (1.3) |

| High school graduate | 5 (3.3) |

| Vocational/technical training | 5 (3.1) |

| Some college | 25 (16.6) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 61 (40.4) |

| Master’s degree | 41 (27.2) |

| Doctorate degree | 12 (7.9) |

| Insurance, n (%) | |

| Uninsured, private pay | 7 (4.4) |

| Employer based | 107 (67.3) |

| Military coverage | 1 (0.6) |

| Medicaid | 12 (7.5) |

| Medicare/disability | 12 (7.5) |

| Relationship to diabetes, n (%) | |

| Living with diabetes | 106 (66.7) |

| Caregiver (ie, parent) | 30 (18.9) |

| Care partner (ie, spouse) | 5 (3.1) |

| Other relationship | 5 (3.1) |

| Type of diabetes managed in the home, n (%) | |

| Type 1 | 129 (80.1) |

| Type 2 | 11 (6.9) |

| Latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood | 4 (2.5) |

| Maturity onset diabetes of the young | 2 (1.3) |

| Surgical | 2 (1.3) |

Underground Exchange of Diabetes Medications and Supplies

Participants identified themselves as donors (56.6%, n = 90), donation receivers (34.6%, n = 55), traders (23.9%, n = 38), purchasers (15.1%, n = 24), and borrowers (22%, n = 35). Underground exchange of diabetes medication and supplies was conducted with various individuals within the personal and online network, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Underground Exchange Activity.

| Family, n (%) | Friend, n (%) | Coworker, n (%) | Online acquaintance, n (%) | Online stranger, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donors (n = 90) | 15 (9.4) | 42 (26.4) | 5 (3.1) | 56 (35.2) | 33 (20.8) |

| Donation receivers (n = 55) | 5 (3.1) | 15 (9.4) | 3 (1.9) | 24 (15.1) | 12 (7.5) |

| Traders (n = 38) | 4 (2.5) | 12 (7.5) | 2 (1.3) | 23 (60.5) | 9 (23.7) |

| Purchasers (n = 24) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 8 (5) | 12 (7.5) |

| Borrowers (n = 35) | 2 (1.3) | 13 (8.2) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (3.1) | 3 (1.9) |

Note. N = 135-156. There may be duplicate responses as some participants stated that they engaged in nontraditional activity with more than one type of person.

Diabetes-related financial stress (eg, Is purchasing diabetes medications and/or supplies financially difficult for you?; coded as yes/no) was related to seeking support from others to increase underground exchange to diabetes medications and supplies through trading (χ2 = 13.26, P = .000), receiving donations (χ2 = 8.5, P = .003, value), and fundraising (χ2 = 7.1, P = .008), but not donating to others, borrowing, or purchasing. Further analysis, using binary logistic regression, identified that financial stress related to the purchase of diabetes medications and supplies predicted engagement in trading diabetes mediations or supplies (OR 6.3, 95% CI 2.2-18.5) and receiving donated medications or supplies (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.1-7.2). When trading did occur (n = 38), trading more often occurred with online acquaintances and strangers (84.2%, n = 31) than with closer contacts (eg, family, friends, and coworkers).

There was no association between self-reported A1C and trading, purchasing, or borrowing diabetes medications and supplies. However, donors were more likely to have a lower self-reported A1C (M = 6.9, SD = 1.0) compared to those who did not donate (M = 7.7, SD = 2.1) to others (P = .003). Furthermore, those who received donations were more likely to have a lower self-reported A1C (M = 7.1, SD = 1.1) compared to those who had never received a donation (M = 7.3, SD = 1.7) in the past 12 months (P = .039).

Qualitative Results

Major themes emerged through the qualitative analysis process and included (1) factors influencing underground exchange activity, (2) perceived benefits of underground exchange activity, and (3) perceived consequences of underground exchange activity. Taken together, these themes describe a landscape and network of underground exchange through social exchange. Respondents donate, trade, borrow, and purchase medications and supplies in both urgent and nonurgent situations, to online strangers and acquaintances and closer contacts (relatives and friends). Traversing all themes and categories is a story of unmet needs. See Table 4 for participant quotes (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Participant Quotes.

| Overarching theme | Subtheme | Categories | Supporting quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmet needs | Factors influencing underground exchange activity | Altruism | I have a poorly insured T1D brother who will get some test strips, insulin, and glucagon from me. I run a surplus always out of fear of losing my job/insurance that it would expire before used. My sister was also T1D and died when she lost her job and I was not in a position to help her. Now that I am—I will help whenever, whomever when needed. In memory of my sister |

| I accidentally received a double shipment of my insulin, and an online friend was struggling and awaiting Medicaid approval. They had been rationing for months. I have plenty, they had none. I cannot let that slide. So, I gave them six vials of Humalog and some extra pump supplies. I continue to bring insulin back from Canada every time I visit for others | |||

| [Donating] is necessary in order to support a healthy community when our free market no longer is truly a free market. We have limited options, few choices, and no competitive prices anymore. Seeing others suffer is too stressful | |||

| Excess medications and supplies | I hoard diabetes supplies in the case of emergency. I also donate these supplies to people who need them because it is not fair for me to have excess while they struggle to survive, or even die, because our healthcare system is broken. I donate until my supply is depleted then hold off until I have built it back up again | ||

| My partner is currently without any medical coverage due to unemployment without unemployment insurance. I have a backlog of Metformin XR, which is also one of his medications. He is using up my backlog to save costs and avoid it from expiring out | |||

| I am so fortunate to have a surplus and to be in excellent financial circumstances. I will ship without charge to a fellow diabetic in need | |||

| Desired commercially unavailable technology | We received an older Medtronic insulin pump for looping. We also purchased another pump as a backup | ||

| I wanted to “downgrade” to an Open APS compatible pump, and an online friend had one that she did not need. I have known this friend online for a while, and she gave me the pump at our most recent in real life meetup | |||

| Cheaper online and offshore | I buy expired test strips from several sources. Then, a person on Craigs list selling test strips asked if I could use insulin too? I said yes, and met her in parking lots to buy, very cloak and dagger. . . | ||

| I lacked health insurance for many years. I found that I could purchase glucose test strips on eBay for far less then I could purchase them at the pharmacy. I bought strips from one seller on eBay for over three years. Before I began purchasing the strips I spoke with the seller to reassure myself | |||

| I ALWAYS buy my two insulins out of the United States, as EVERY OTHER COUNTRY is a FRACTION of the price of what is available in the United States for diabetics without insurance | |||

| Perceived benefits of underground exchange activity | Preventing hospitalization and death | I most likely would have ended up hospitalized with ketoacidosis, but I was lucky enough to get insulin from another person | |

| I would have ended up in the emergency room with more bills I cannot pay | |||

| My coworker avoided going to the hospital because I donated insulin to them | |||

| Preventing bureaucratic delays in care | Our insurance has not provided insulin for the past six months even with doctor writing for prior authorization and appealing. Finally, the insurance approved it with the second prior authorization but it cost $6600 to pick up from pharmacy. It is still being held hostage at the pharmacy. So, I borrowed some from a stranger | ||

| My insurance was not getting things done fast enough and I was running out of sensors. A friend mailed me some and I returned the same amount when I got my supply | |||

| Out of town, pump ran empty and my daughter had not grabbed more insulin. Asked an acquaintance if she was in that town and had some we could borrow/have. Pump was filled. Much faster than calling doctor for an emergency refill Trading was great. We both got our needs met and there was less hassle than fight with insurance companies | |||

| Ability to try before you buy | A friend of a friend wanted to try a few pumps before deciding on one. I lent them my old pump and related supplies to test drive for a month | ||

| I purchased Fiasp offshore before it was commercially available in the United States to see what it was like | |||

| Perceived consequences of underground exchange activity | Financial burden | It kept her safe, but caused me to order new medication and supplies sooner, costing me more overall than I would have spent if she had coverage | |

| Most of the time I donated supplies because I wanted to help, but sometimes I also donated supplies to try and “prove myself” so that others would trust me enough to trade other supplies that I needed much more | |||

| Potential safety issues | Transmitters for Dexcom with expired batteries | ||

| The people who donated the supplies were completely honest about them being expired sensors, but I was fine with that. I reimbursed them for their shipping costs but paid nothing for the supplies | |||

| Word was spread of my need, many knew I welcomed expired insulin, test strips and so I would be offered them. I also was sometimes given NON expired supplies from people that had switched brands . . . |

Abbreviation: T1D, type 1 diabetes.

Figure 1.

Overarching theme, subthemes, and categories.

Factors Influencing Underground Exchange Activity

Altruism

Participants felt compelled to donate diabetes medication and supplies because they recognized the dire need of others, despite needing the medications and supplies themselves. Participants did not want to see people, who like them also had diabetes, stress or suffer due to inability to access basic diabetes needs. In fact, participants described a sense of duty or internal obligation to help another if they were in a position to help. This help included donating, trading, or borrowing diabetes medications and/or supplies. Sometimes, the person providing the diabetes medications and/or supplies would even pay for shipping, though sometimes the person on the receiving end paid for shipping. Some described a cyclical nature of donation, whereas they were once a person in need, and now, they “pay it forward” or “give back.” For example, one person described that at one point she was able to use a friend’s continuous glucose monitor (CGM). Later, when that same friend’s insulin pump broke, she let her friend use her insulin pump temporarily while she was on a pump vacation. Help did not stop at providing medications and supplies. Participants also reported providing instrumental support in the form of time and service. One respondent shared a story of helping a homeless family with a newly diagnosed child to find work, an apartment, and a car to “get her a head start.” Donations based in altruism were also made in response to natural disasters, such as hurricanes and floods. Generally, participants described, “we are a community, we take care of each other.”

Excess medications and supplies

Overtime, some participants described building up a stockpile of medications and supplies that allowed them to be in a position to donate. Individuals, however, would not donate if doing so compromised their own health. Therefore, they would only help others if they were in a position to do so. Once a participant did donate their stockpile, they would work toward building up their supply again, in anticipation to donate to another person in need. Excess medications included pills, insulin, and glucagon, while excess supplies included glucose strips, sensors, and pump supplies.

Desired commercially unavailable technology

Individuals interested in off-label use of open source artificial pancreas systems (ie, OpenAPS) required insulin pumps that were not commercially available for purchase. Because of this, they turned to the internet to seek out the necessary devices. In some cases, individuals were receiving insulin pumps for free. Though some were willing to purchase out of warranty insulin pumps from online strangers as well.

Cheaper online and offshore

Individuals sought alterative options after being unable to adequately access medications and supplies using their health insurance. For example, eBay was a popular site to purchase glucose strips. Extra steps, such as comparing strips purchased online with those that were not, were taken to assure strips purchased from online sources would be accurate. Insulin is being purchased from outside of the United States as a cheaper alternative. Some were having their friends or family purchase insulin from a Canada or Puerto Rico pharmacy and shipping it to them in the United States. Those in closer proximity to Canada or Mexico were willing to drive across the border in order to make the purchase themselves. Even considering the shipping and travel costs, accessing insulin offshore was more accessible for those with and without health insurance.

Perceived Benefits to Underground Exchange Activity

Preventing hospitalization and death

Without the ability to access medications and supplies through their personal and online network, individuals were frank in knowing they ran the risk of out of range glucose levels, diabetic ketoacidosis, and even death. Those who accessed pump supplies through an underground exchange noted that the alternative would have meant a return to multiple daily injections. Returning to injections would result in “a negative impact on my blood glucose with extreme highs and lows” or “a higher A1C.” Both PWD and parents to children with diabetes reported that if they did not access medications and supplies through an underground exchange, they would have gone to the emergency room. Participants further described that emergency room visits would only temporarily help them and increase financial distress considerably. In this way, the underground exchange of medications mitigated the possibility of more severe health and financial consequences.

Preventing bureaucratic delays in care

Health insurance, provider offices, pharmacies, and durable medical equipment companies were unpredictable regarding when medications and supplies would be authorized and shipped, and whether or not they would be affordable. It could also take days before prescription refills were authorized by providers, delaying one’s ability to pick up their prescriptions. Due to healthcare system inefficiencies, timely access to necessary diabetes medications and supplies, that was also affordable, was challenging. There were several instances in which participants found themselves in a situation where they urgently needed insulin (ie, did not bring enough insulin while on vacation, forgot to bring home insulin from hotel, dropped insulin vial, could not afford insulin with health insurance). As such, people turned to others, including family, friends, coworkers, and even online strangers, for solutions. The solutions offered by a personal and online network provided was often times more timely and affordable access compared to a more traditional approach to receiving medications/supplies. Though some participants described feeling intimidated by going online to engage in underground trading and donating, understanding that medical fraud was occurring, they justified their actions because of system failures (ie, pharmaceutical companies are allowed to overcharge, poor health insurance coverage) and their desire to live.

Ability to try before you buy

A handful of participants described a process of trialing medications or supplies before committing to its purchase in an attempt to understand what worked best for them without the financial commitment. Such trials included different brands of insulin, insulin pumps, and continuous glucose monitors and occurred only in those who identified to be having type 1 diabetes (T1D). This process was similar to using a medication or glucometer sample that would be provided by a healthcare provider. The ability to try medications and supplies increases one’s confidence in committing to specific diabetes technology and also provides information about how effective various medications were on an individual level.

Perceived Consequences to Underground Exchange

Financial burden

Some participants who donated medications and supplied to others in need reported financial consequences. Not everyone was in a position to help others, yet, felt compelled to do so because of the need of others. For example, one respondent shared a story of giving insulin and CGM sensors to her sister in need, even though she did not have extra to spare. As such, this participant had to spend extra money on additional insulin and sensors for herself.

Potential safety issues

Participants received donations from others were often notified if the medications or supply was potentially compromised (ie, expired, not stored properly) and opted to use the medication and/or supply despite the potential risks. Though only three cases, problems with shipping carriers via mail or with receiving supplies that did not function as expected were reported. For example, one person indicated that they used insulin known to not be refrigerated. In another case, a participant received an item that did not work as described, they received a CGM transmitter that would not work and appeared to be “dead.” There were no reports of untoward effects related to the use of diabetes medications and supplies obtained through donation, trading, purchasing, or borrowing.

A Theory of Access Revised

After examining the Theory of Access framework originally developed by Penchansky and Thomas18 which included five dimensions (accessibility, availability, acceptability, affordability, and adequacy) and modified by Saurman19 to add a sixth dimension, awareness; we feel another modification is necessary. We identified several instances in which “association” by personal and online networks was necessary to access diabetes medications and supplies. Table 5 describes dimensions of access in the context of our study findings.

Table 5.

Dimensions of Access in Context of Study Findings.

| Dimension of access | Definition | Examples from study findings |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibilitya | Location | Emergency needs while on vacation |

| Availabilitya | Supply and demand | Delayed refills from healthcare providers Delayed shipment from mail-order pharmacy or durable medical equipment company Delayed approval from insurance company |

| Acceptabilitya | Patient perception | Patient unwilling to accept social norms related to how diabetes medications and supplies are accessed given affordability and availability limitations. As a result, patients opt to engage in donating, trading, borrowing, and purchasing from others |

| Affordabilitya | Financial and incidental costs | Challenges existed related to being able to afford diabetes medications and supplies due to high costs |

| Adequacya | Organization | Current systems (insurance, industry, pharmacies, and healthcare provider clinics) are not always organized in a way that are patient-centered to support patient diabetes medication and supply needs |

| Awarenessb | Communication and information | Coupons and patient assistance programs are not known and understood, and when they are, patients do not always benefit Patients sometimes do not understand their insurance coverage and associated access to diabetes medications and supplies |

| Associationc | Network | Community available to help someone in need to prevent adverse events given the other access dimensions Ability to try a diabetes medication or supply before committing to purchasing |

Discussion

This study aimed to describe the real-world phenomenon of individuals and families affected by diabetes who engage in such activities to better understand how often and under what circumstances it is occurring, and to examine any positive or negative safety implications related to this activity. The high cost of diabetes supplies and medications has placed significant burden on patients and families living with diabetes. As a result, some have turned to an underground exchange to obtain necessary medications and supplies, such as utilizing DOCs, to facilitate donating, trading, and borrowing.

In this study, participants described turning to peers with diabetes when they faced barriers to accessing diabetes medications and supplies in order to be healthy. In some cases, these were people they had never met nor had any relationship with. With the explosion of social media, there is a high likelihood that an online acquaintance may be someone which the person affected by diabetes has not actually met. Our study sheds new light on the use of social media as a means to an underground exchange of diabetes medications and supplies. Similar to our study, others20 have found altruism to be a factor related to engaging with underground exchange activity. Importantly, the evidence indicates that individuals who have shared or borrowed medications in the past are likely to do so again in the future.21 Indeed, healthcare provider perception of sharing behaviors is multidimensional, suggesting that there are perceived positive consequences, along with the negative, to underground exchange activity.22

While our results indicate that a “buyers club” exchange is occurring online within in the context of diabetes medication and supplies, there is typically no actual exchange of money deriving economic benefit between people affected by diabetes. When exchange of money did occur between people affected by diabetes, it was usually to cover shipping costs or the purchase of outdated insulin pumps. Other research suggests that financial gain may be occurring related to the global underground exchange of continuous glucose monitoring devices.23 Legal sharing of medications does exist in 38 states and Guam, allowing unused prescription drugs to be donated and redispensed to individuals meeting specific criteria, though most states do not have an active program.24 Among some active programs, individuals need to be below 200% of the poverty level. In the present study, individuals were struggling to purchase diabetes medications and supplies despite most having insurance and living above the poverty level.

Very few participants reported changing their medications or supply from brand name to generic. Perhaps this is because of the lack of awareness of generic alternatives, but could also be due to concerns about the pharmacokinetic and/or pharmacodynamic differences. Studies have shown mixed results when comparing analog to generic insulin with regard to hypoglycemia.25-28 Furthermore, nonmedical switching is associated with worsening quality of life and worsening glycemic outcomes.29

Though medication and supply safety issues were not identified in this study, it is possible that underground exchange activity could result in untoward health outcomes. Other research has examined how individuals assess safety related to sharing FDA approved medications. Such assessments include past illness experiences and knowledge of medications, and symptom matching.20 Given the various types of insulin and other diabetes medications on the market, it is possible that someone might take a dose of donated, traded, or borrowed medication they believe is equivalent to a dose they normally take, but it is not. For example, someone could take a dose of donated rapid-acting insulin, thinking it acts similar to their long-acting insulin, and experience severe hypoglycemia. Temperature issues during storage and shipping are also of concern as they can influence the efficacy of some medications and supplies.

Healthcare providers should proactively engage in conversations with their patients about access to diabetes medications and supplies to trigger discussions about safety and refer to resources as appropriate. Simply asking patients if they experience any difficulty purchasing diabetes medications or supplies could help identify those in need of additional support. Healthcare providers and support staff should be trained to help patients apply for industry assistance when appropriate. Furthermore, healthcare provider engagement in health policy could help policy-makers better understand the access issues people affected by diabetes face.

From a policy standpoint, if access does not improve, healthcare providers may find themselves being forced to train patients how to safely engage in underground exchange practices.

Study participants did not want to engage in the underground exchange of diabetes medication and supplies, but were faced with unmet needs due to health and health care inequities. As such, participants were willing to accept the risk of using diabetes medications and supplies from others in order to stay healthy. Pharmaceutical companies, pharmacy benefit managers, and insurance companies need to understand how their financial decision making is impacting individual PWD. New drug development must be balanced with an understanding of the impact of cost on PWD and their families. A common rally cry within social media groups is “patients over profit.” In order for patients to come first, drastic changes and transparency are necessary to disrupt health access inequities faced by those living with diabetes. According to the dimensions of access (Table 5), if diabetes medications and supplies were readily accessible, such underground exchange activities would not be necessary. Unfortunately, there are PWD who experience access issues, even by association, that have died as a result of said lack of access.

A strength of this study is the mixed-method approach, convergently analyzing both quantitative and qualitative data to examine a taboo topic that is not well understood. Given selection and response bias, it is possible that findings may not be generalizable. Importantly, this study recruited individuals who are either using Facebook or Twitter who may have an increased level of connectedness to others. Underground exchange activity is unknown for those not using the internet. This sample was also highly educated, though experiencing various levels of income. Additionally, the sample was mostly non-Hispanic white and managing T1D. Race and ethnicity has been associated with medication sharing,30 as such, the majority non-Hispanic white participants in this study indicate a wider access issue. Individuals with type 2 diabetes, especially those experiencing the Medicare gap (also known as “donut hole”), may also be engaging in underground exchange to diabetes medications and supplies, though a small percentage in this sample (7.5%) was on Medicare. We did not ask about interruptions in insurance, which has been linked to elevated A1C31 and diabetic ketoacidosis.32 Further research is needed to elicit safety related to underground exchange activities.

Conclusion

People affected by diabetes are engaging in underground exchange to diabetes medications and supplies due to financial barriers and bureaucratic delays in care. Without accessing a network of family, friends, and most often, online strangers, individuals would be at risk for serious acute complications. Importantly, PWD should not be forced to engage in an underground exchange activity in order to live. Healthcare providers must be aware that such activity exists and proactively inquire about safety and possible alternative resources. Health policy makers need to examine ways to make diabetes management more accessible to prevent unnecessary hospitalization and death.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Online_Trading_Questionaire_Supplement for The Underground Exchange of Diabetes Medications and Supplies: Donating, Trading, and Borrowing, Oh My! by Michelle L. Litchman, Tamara K. Oser, Sarah E. Wawrzynski, Heather R. Walker and Sean Oser in Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was partially funded by the University of Utah College of Nursing Health Equity Resilience and Education Research Innovation Team.

ORCID iDs: Michelle L. Litchman  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8928-5748

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8928-5748

Tamara K. Oser  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0405-3420

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0405-3420

Sarah E. Wawrzynski  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2756-2583

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2756-2583

Heather R. Walker  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1134-5779

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1134-5779

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Biniek JF, Johnson W. Spending on Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes and the Role of Rapidly Increasing Insulin Prices. Health Care Cost Institute; 2019. https://healthcostinstitute.org/images/easyblog_articles/267/HCCI-Insulin-Use-and-Spending-Trends-Brief-01.22.19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cefalu WT, Dawes DE, Gavlak G, et al. Insulin access and affordability working group: conclusions and recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(6):1299-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berchick ER, Hood E, Barnett JC. Current Population Reports, P60-264, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2017. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herkert DM, Vijayakumar P, Luo J, et al. Cost-related insulin underuse is common and associated with poor glycemic control. Diabetes. 2018; 67(Suppl1). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sable-Smith B. Insulin’s high cost leads to lethal rationing. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/09/01/641615877/insulins-high-cost-leads-to-lethal-rationing. Accessed September 1, 2018.

- 6. Konrad W. Black market insulin: what you need to know. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/black-market-insulin-what-you-need-to-know/. Accessed June 20, 2017.

- 7. Mullard A. Underground drug networks in the early days of AIDS. Lancet. 2014;383(9917):592. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vernaz-Hegi N, Calmy A, Hurst S, et al. A buyers’ club to improve access to hepatitis C treatment for vulnerable populations. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018;148:w14649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adriance S. Fighting for the ‘right to try’ unapproved drugs: law as persuasion. Yale LJF. 2014;124:148. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Litchman ML, Walker HR, Ng AH, et al. State of the science: a scoping review and gap analysis of diabetes online communities. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2019;13(3):466-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hilliard ME, Sparling KM, Hitchcock J, Oser TK, Hood KK. The emerging diabetes online community. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2015;11(4):261-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prawitz A, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, O’Neill B, Kim J, Drentea P. Incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. Financ Couns Plan. 2006;17(1):34-50. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morgan DL. Qualitative content analysis: a guide to paths not taken. Qual Health Res. 1993;3(1):112-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tesch R. Qualitative Research: Analysis Types and Software Tools. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morse JM. The Significance of Saturation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saurman E. Improving access: modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s Theory of Access. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2016;21(1):36-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beyene K, Aspden T, Sheridan J. Prescription medicine sharing: exploring patients’ beliefs and experiences. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2016;9(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beyene K, Aspden T, Sheridan J. Prevalence and predictors of medicine saving and future prescription medicine sharing: findings from a New Zealand online survey. Int J Pharm Pract. 2019;27(2):166-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beyene KA, Aspden TJ, Sheridan JL. A qualitative exploration of healthcare providers’ perspectives on patients’ non-recreational, prescription medicines sharing behaviours. J Pharm Pract Res. 2018;48(2):158-166. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Onisie O, Crocket H, de Bock M. The CGM grey market: a reflection of global access inequity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(11):823-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cauchi R, Berg K. State Prescription Drug Return, Reuse and Recycling Laws. 2018. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-prescription-drug-return-reuse-and-recycling.aspx. Accessed June 7, 2019.

- 25. Owens DR, Traylor L, Mullins P, Landgraf W. Patient-level meta-analysis of efficacy and hypoglycaemia in people with type 2 diabetes initiating insulin glargine 100 U/mL or neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin analysed according to concomitant oral antidiabetes therapy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;124:57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lipska KJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, Huang ES, Karter AJ. Association of initiation of basal insulin analogs vs neutral protamine hagedorn insulin with hypoglycemia-related emergency department visits or hospital admissions and with glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;320(1):53-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Strandberg AY, Khanfir H, Makimattila S, Saukkonen T, Strandberg TE, Hoti F. Insulins NPH, glargine, and detemir, and risk of severe hypoglycemia among working-age adults. Ann Med. 2017;49(4):357-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kristensen PL, Tarnow L, Bay C, et al. Comparing effects of insulin analogues and human insulin on nocturnal glycaemia in hypoglycaemia-prone people with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2017;34(5):625-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Flores NM, Patel CA, Bookhart BK, Bacchus S. Consequences of non-medical switch among patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(8):1475-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beyene KA, Sheridan J, Aspden T. Prescription medication sharing: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):e15-e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rogers MAM, Lee JM, Tipirneni R, Banerjee T, Kim C. Interruptions in private health insurance and outcomes in adults with type 1 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Health Aff. 2018;37(7):1024-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gaffney A, Christopher A, Katz A, et al. The incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis during “emerging adulthood” in the USA and Canada: a population-based study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1244-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Online_Trading_Questionaire_Supplement for The Underground Exchange of Diabetes Medications and Supplies: Donating, Trading, and Borrowing, Oh My! by Michelle L. Litchman, Tamara K. Oser, Sarah E. Wawrzynski, Heather R. Walker and Sean Oser in Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology