Abstract

Background

The safety and efficacy of the TuBridge flow diverter in treating middle cerebral artery aneurysms remains unknown. In this study, we report our preliminary experience treating complex middle cerebral artery aneurysms using the TuBridge flow diverter.

Methods

A prospectively maintained database of intracranial aneurysms treated with the TuBridge flow diverter was retrospectively reviewed, and patients with middle cerebral artery aneurysms were included in this study. Demographics, aneurysm features, complications, and clinical and angiographic outcomes were assessed. Evaluation of the angiographic results included occlusion grade of aneurysm (O’Kelly–Marotta grading scale), patency of jailed branch(es), and in-stent stenosis.

Results

Eight patients with eight middle cerebral artery aneurysms were included in this study. The mean aneurysm size was 11.8 ± 6.8 mm. There were no procedure-related complications and there was no morbidity or mortality at a mean follow-up of 11.3 ± 3.6 months. All patients had follow-up angiograms at a mean of 7.5 ± 4.0 months after surgery. Of the eight patients, there was 1 (12.5%) O’Kelly–Marotta grading scale A, 3 (37.5%) O’Kelly–Marotta grading scale B, 1 (12.5%) O’Kelly–Marotta grading scale C, and 3 (37.5%) O’Kelly–Marotta grading scale D. Of the seven patients with jailed branch, the blood flow of jailed branch was unchanged in 4 (57.1%), decreased in 2 (28.6%), and occluded in 1 (14.3%). In-stent stenosis was mild in 2 (25%) patients and moderate in 1 (12.5%) patient.

Conclusion

Midterm results suggest that endovascular treatment of middle cerebral artery aneurysms using the TuBridge flow diverter is safe and associated with good outcomes. The TuBridge flow diverter may be an option for complex middle cerebral artery aneurysms that are difficult to treat with either clipping or coiling.

Keywords: TuBridge flow diverter, endovascular treatment, middle cerebral artery aneurysm

Background

Middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysms are primarily treated with either microsurgical clipping or endovascular coiling.1 However, fusiform aneurysms, recurrent aneurysms, or aneurysms with distal branches arising from the aneurysm sac remain difficult to treat.2 Morbidity or insufficient occlusion is not uncommon after treatment of these types of aneurysms.3

In the past decade, the flow diverter device (FDD) had become an important option for the treatment of aneurysm.4 By producing a flow diversion effect, an FDD induces intra-aneurysmal thrombosis while preserving the normal flow in the parent artery and its branches, eventually leading to healing of the neointima across the neck of the aneurysm.5,6

The TuBridge flow diverter (TFD; MicroPort, Shanghai, China) is a nickel–titanium braided, self-expandable stent-like device with flared ends (Figure 1).7 TFDs are available in diameters of 2.5 mm to 6.5 mm and lengths of 12 mm to 45 mm. The TFD is composed of either 64 microfilaments (diameter ≥3.5 mm) or 48 microfilaments (diameter < 3.5 mm). The TFD also contains two double-helix platinum–iridium radiopaque microfilaments that improve the visibility of the TFD under fluoroscopy. When fully opened, a TFD provides 30–35% surface coverage at the nominal diameter.8

Figure 1.

Photograph of the TFD. The flared ends of the TFD improve wall apposition and the double-helix platinum–iridium radiopaque microfilaments increase device visibility under fluoroscopy.

TFDs have been reported to be safe and effective in the treatment of internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysms and vertebral artery (VA) aneurysms and its use was approved by the Chinese Food and Drug Administration in 2018.8,9 However, the safety and efficacy of this device in treating MCA aneurysms are unknown.

We have used TFDs to treat the complex MCA aneurysms since 2018. Herein, we presented our preliminary experience of the treatment of MCA aneurysms with TFDs.

Methods

Patient characteristics and aneurysm features

The study was approved by the Local Institutional Review board. We reviewed a prospectively maintained database of intracranial aneurysms and identified patients with MCA aneurysms treated with TFDs. Data extracted included patient demographic information, aneurysm features, complications, clinical outcomes, and immediate postoperative and follow-up angiography results. Aneurysm features including location, morphology, size, and the diameters of the proximal and distal parent arteries were obtained by digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and three-dimensional rotational angiography (3DRA). Aneurysm location was classified as M1, MCA bifurcation, and M2. M1 was defined as MCA between the origin and the bifurcation. And M2 was the MCA from the bifurcation to the circular sulcus of the insula. Aneurysm morphology was categorized as saccular, fusiform, or dissecting. Aneurysm size was classified as small (<10 mm), large (10–24 mm), and giant (≥25 mm). Information regarding the rupture status of aneurysm and previous treatment of recurrent aneurysms was also extracted.

Antiplatelet therapy

In all patients, dual antiplatelet therapy was initiated at least five days before the procedure. In addition, all patients received CYP2C19 genotyping. Aspirin 300 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day were used for patients with genotype *1/*1, and aspirin 100 mg/day and ticagrelor 180 mg/day were used for patients who were not genotype *1/*1. Thrombelastograms (TEGs) were performed to be certain that inhibition of arachidonic acid (AA) was >50% and <90%, adenosine diphosphate (ADP) >30% and <90% before the procedure. Dual antiplatelet therapy was continued until six months after the procedure, followed by permanent aspirin treatment at 300 mg/day.

Endovascular procedure

The endovascular procedure was performed under general anesthesia. A 5-French diagnostic catheter was navigated to the ipsilateral ICA and then exchanged for a 6 F 90 cm Shuttle sheath (Cook, Bloomington, Indiana, USA). A 6 F Navien catheter (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) was advanced within the Shuttle sheath to reach the cavernous segment of ICA. A 0.029-inch T-track microcatheter (MicroPort, Shanghai, China) was navigated into a straight portion of M2 or M3, which was distal to the aneurysm, with a Synchro-14 microwire (Stryker, Fremont, California, USA). The TFD was advanced into the T-track microcatheter and then slowly unsheathed by alternately advancing the delivery wire and pulling gently on the microcatheter in order to obtain optimal stent opening and wall apposition. The distal and proximal end of the stent should be landed at least 5 mm away from the aneurysm neck.

When the TFD was deployed, a J-shaped-tip Synchro-14 microwire together with the microcatheter was pushed back into the stent and massaged it. Syngo Dyna CT (Siemens, Munich, Germany) was performed to evaluate the wall apposition of the stent. In the case of incomplete apposition, ScepterC balloon (Microvention, Tustin, California, USA) angioplasty was performed.

For concomitant coiling, an Envoy guide catheter (Cordis, Fremont, California, USA) was advanced into the ICA via contralateral femoral artery access. Excelsior SL-10 microcatheter (Stryker, Fremont, California, USA) was navigated into the aneurysm sac to deliver Axium coils (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA).

Complications and follow-up

Procedure-related complications including hemorrhagic and thromboembolic events were recorded. Symptomatic complications were defined as those associated with transient or permanent neurological deficits. Patients were followed up by an office visit or telephone call at three months, six months, and thereafter every six months after the procedure. Clinical outcomes were assessed using modified Rankin Scale (mRS). Morbidity was defined as any increase in the mRS score after the procedure.

Angiographic outcomes

Angiographic outcome was assessed using the O’Kelly–Marotta grading scale (OKM).10 Aneurysm filling was graded as: A, complete (>95%); B, incomplete (5–95%); C, neck remnant (<5%); D, no filling (0%). Stasis was graded as: 1, no stasis (clearance of contrast within the arterial phase); 2, moderate stasis (clearance of contrast prior to the venous phase); 3, significant stasis (contrast persists in the aneurysm into the venous phase and beyond). OKM aneurysm filling of C or D was considered favorable aneurysm occlusion.

On follow-up angiography, the “jailed” artery was also evaluated. Jailed artery flow was classified into three levels: unchanged (concentration of contrast within the artery and diameter of the vessel are both similar to that before the procedure); decreased (either the concentration of contrast within the artery or the diameter of the vessel is lower than that before the procedure, or filling of contrast is delayed to a greater degree) and occluded (the vessel was not seen).

In-stent stenosis was also evaluated on follow-up angiography. In-stent stenosis was defined as endothelium growth beyond the limits of the stent wall, which was seen as a “gap” between the intra-lumen filling of contrast and the metallic mesh of the stent on angiogram. Less than 25% loss of lumen was considered intimal hyperplasia. In-stent stenosis was categorized as mild (26–50%), moderate (51–75%), and severe (>75%).11

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. All statistical tests were performed using STATA 13.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and aneurysm features

Eight patients with MCA aneurysms treated with TFDs from July 2018 to December 2019 were identified in the database and included in the analysis. There were four males and four females, with a mean age of 54.4 ± 10.4 years. The aneurysm was located in M1 in 3 (37.5%) patients, in MCA bifurcation in 4 (50%) patients, and in M2 in 1(12.5%) patient. The mean aneurysm size was 11.8 ± 6.8 mm, and there were 2 (25%) small aneurysms, 5 (62.5%) large aneurysms, and 1 (12.5%) giant aneurysm. Aneurysm morphology was saccular in 2 (75%) patients and fusiform in 6 (75%) patients. The mean diameters of the proximal parent artery and the distal parent artery were 3.0 ± 0.1 mm and 2.8 ± 0.3 mm, respectively. Seven of the aneurysms were unruptured and one had ruptured one month before the procedure. There were 2 (25%) recurrent aneurysms, which were previously treated by clipping. The diameters of these two aneurysms before clipping were 26 mm and 10 mm, respectively. Patient demographics and aneurysm features are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data, aneurysm features, clinical and angiographic results.

| Case | Sex | Age (years) | Site | Type of aneurysm | Rupture status | Size (mm) | Diameters of parent artery (proximal/distal, mm) | Recurrent aneurysm (previous treatment) | Concomitant coiling | Jailed branch | Immediate OKM | Increase of mRS in FU (months) | FU OKM (months) | FU jailed branch flow | In-stent stenosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 55 | MCA B | Fusiform | Unruptured | 26 | 3.0/3.2 | Yes (clipping) | Yes | Yes | B3 | No (18) | D (18) | Occluded | Moderate |

| 2 | F | 52 | M1 | Saccular | Ruptured 1 month before | 3 | 3.0/3.1 | No | No | Yes | A1 | No (12) | D (6) | Unchanged | Mild |

| 3 | F | 62 | M2 | Fusiform | Unruptured | 8 | 2.9/2.6 | No | No | No | A1 | No (12) | C2 (6) | N/A | No |

| 4 | M | 50 | M1 | Fusiform | Unruptured | 12 | 3.1/2.8 | No | No | Yes | B3 | No (12) | D (6) | Unchanged | No |

| 5 | F | 61 | MCA B | Fusiform | Unruptured | 10 | 3.2/3.0 | No | No | Yes | A1 | No (12) | B1 (6) | Unchanged | No |

| 6 | M | 30 | MCA B | Fusiform | Unruptured | 11 | 2.9/2.5 | No | No | Yes | A1 | No (12) | A1 (6) | Decreased | No |

| 7 | M | 61 | M1 | Fusiform | Unruptured | 14 | 3.2/3.0 | No | No | Yes | B3 | No (6) | B3 (6) | Decreased | Mild |

| 8 | M | 64 | MCA B | Saccular | Unruptured | 10 | 2.8/2.5 | Yes (clipping) | No | Yes | B3 | No (6) | B3 (6) | Unchanged | No |

F: female; FU: follow-up; M: male; MCA B: middle cerebral artery bifurcation; mRS: modified Rankin scale; N/A: not applicable; OKM: O’Kelly–Marotta grading scale.

Angiography results

TFDs were successfully deployed in all eight patients and all eight patients were treated with a single TFD. Seven patients had “jailed” arteries; one patient with an M2 aneurysm did not have a jailed branch (case 3). Concomitant coiling was performed in 1 (12.5%) patient (case 1, Figure 2). Coil-assisted stent deployment was performed in a patient with an M1 fusiform aneurysm (case 7, Figure 3). Balloon angioplasty was needed to improve wall apposition of the TFD in 1 (12.5%) patient (case 2, Figure 4).

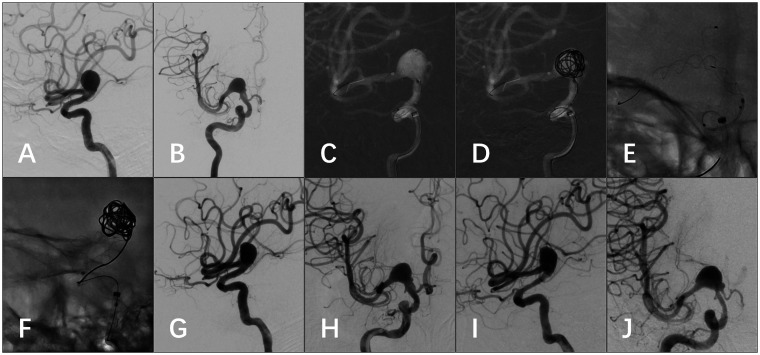

Figure 2.

(a) CTA demonstrated a left MCA bifurcation giant aneurysm involving distal M1 and the superior trunk of M2. The inferior trunk of M2 was not visible. (b) Post-clipping CTA demonstrated the reconstructed aneurysm with stenotic M1 and patent distal vessels. The inferior trunk of M2 emerged (white arrow). (c) Six-month follow-up angiogram demonstrated a major recurrence of the aneurysm with a daughter sac in the proximal part (white arrowhead). (d) Post-procedure un-subtracted image showed the TFD landed in M1 and the superior trunk of M2 and loose packing of the aneurysm with coils. (e) Immediate postoperative angiogram demonstrated decreased flow of the inferior trunk of M2 (black arrows). (f) Angiogram six months after surgery showed the proximal part of the aneurysm was thrombosed, M1 was stenotic, and the inferior trunk of M2 was invisible. (g) On 18-month follow-up angiogram, the aneurysm was completely occluded; the distal M1 and the superior trunk of M2 were reconstructed. However, the distal M1 was still moderately stenotic and the inferior trunk of M2 was occluded (black arrowheads). (h) Eighteen-month follow-up angiogram of the external carotid artery showed that a collateral blood supply was established from the middle meningeal artery to the distal vessels of inferior trunk of M2 (hollow arrows).

Figure 3.

(a and b) Pre-procedure angiogram demonstrated a right proximal M1 fusiform aneurysm involving part of the ICA bifurcation. (c and d) When the TFD was passing through the acute angle of the vessel, the aneurysm was temporally filled with a coil to support the stent. (e) After the stent passed the acute angle, the coil was retrieved to inspect the wall apposition of the TFD. (f) Lateral view of the TFD deployed with support of a coil in the aneurysm. (g and h) Post-procedure angiogram demonstrated decreased filling of the aneurysm and patent jailed artery of A1. (i and j) Angiogram at six months after surgery showed the filling of aneurysm was decreased, the blood flow of the jailed A1 was decreased, and ICA was mildly stenotic.

Figure 4.

(a and b) CTA and DSA demonstrated a left M1 perforator artery aneurysm of 3 mm (white arrow). (c) After stent deployment, the wall apposition of the proximal end was not sufficient (white arrowhead). (d) Balloon angioplasty was performed to improve wall apposition of the proximal end of the stent. (e and f) Immediate postoperative angiogram demonstrated improved wall apposition (black arrow) and patent jailed perforators. (g and h) Angiogram at six months after surgery demonstrated that the aneurysm was completed occluded (black arrowhead), the blood flow of the jailed perforators was unchanged, and M1 was mildly stenotic.

Immediate angiogram after TFD deployment demonstrated OKM filling grade A in 4 (50%) patients and grade B in 4 (50%) patients. The stasis grading scale was 1 in 4 (50%) patients and 3 in 4 (50%) patients.

Follow-up angiograms were performed a mean of 7.5 ± 4.0 months after surgery in all patients. Of the 8 aneurysms, 1 (12.5%) was OKM A, 3 (37.5%) were OKM B, 1 (12.5%) was OKM C, and 3 (37.5%) were OKM D. Thus, favorable aneurysm occlusion (OKM C + D) was obtained in 4 (50%) aneurysms. Stasis grade was 1 in 2 (25%) patients, 2 in 1 (12.5%) patient, and 3 in 2 (25%) patients. Of the seven patients with jailed branch, the blood flow in the jailed branch was unchanged in 4 (57.1%) patients, decreased in 2 (28.6%) patients, and occluded in 1 (14.3%) patient. In-stent stenosis was detected in three patients (37.5%) at a mean of six months. The in-stent stenosis was mild in 2 (25%) patients and moderate in 1 (12.5%) patient. Angiography results are summarized in Table 1.

Complications and clinical outcomes

There were no procedure-related complications. At the last follow-up, a mean of 11.3 ± 3.6 months after surgery, there were no morbidities and no mortalities.

Illustrative case

A 55-year-old female complained of intermittent headache for five months (case 1, Figure 2). Computed tomography angiography (CTA) demonstrated a left MCA bifurcation fusiform aneurysm of 26 mm, involving distal M1 and both trunks of M2. The aneurysm was reconstructed by clipping, which achieved a volume reduction of >80% and preservation of both trunks of M2. Postoperative CTA demonstrated the clipped aneurysm, a segmental stenotic distal M1, a patent superior trunk of M2, and a patent inferior trunk of M2. The patient was discharged without any neurological deficits.

At six-month follow-up after surgery, angiography demonstrated a major recurrence of the aneurysm with a daughter sac close to the proximal end. Conventional clipping, coiling, or stent-assisted coiling was not feasible for the recurrent aneurysm. Trapping of the aneurysm combined with extracranial–intracranial (EC-IC) bypass would be difficult because it was a reoperation. Therefore, it was decided to treat the aneurysm with a TFD. Dual antiplatelet administration was begun five days before the procedure (aspirin 300 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day). The operative plan was to land the TFD in M1 and the superior trunk of M2. The proximal and distal diameters of the parent artery were 3.0 mm and 3.2 mm, respectively. The longest length of TFDs with a caliber of 3.5 mm or less was only 35 mm, which was not long enough to cover at least 5 mm of both the proximal and distal parent arteries. Therefore, a 4.0 mm × 45 mm TFD was implanted to rebuild M1 and the superior trunk of M2. The proximal part of the aneurysm sac was loosely packed with Axium coils in order to support the TFD to pass through the angle of the vessel, as well as to induce intra-aneurysmal thrombosis around the daughter sac. The inferior trunk arose from the proximal part of the aneurysm wall and the flow decreased immediately after the treatment. The patient remained neurological intact after the procedure.

Six months after implantation of the TFD, the proximal part of the aneurysm and the daughter sac were thrombosed and the inferior trunk of M2 was occluded. The distal portion of M1 exhibited moderate stenosis. At six months, dual antiplatelet was switched to aspirin 300 mg/day. At 18-month follow-up, the entire aneurysm was occluded and the moderate stenosis of distal M1 was unchanged. Collateral blood supply from the middle meningeal artery to the distal vessels of the inferior trunk of M2 was noted on angiography. The patient was neurological intact, with a mRS = 0.

Discussion

TFDs have been reported to be safe and effective for the treatment of ICA aneurysms and VA aneurysms.7–9 However, to our knowledge, this is the first report of using TFDs to treat MCA aneurysms.

The differences between the TFD and other FDDs

Pipeline,12–14 Silk,15 and P6416,17 flow diverters have been used for treating MCA aneurysms. Like the Silk and P64, the TFD is made of a nickel–titanium alloy which exhibits shape memory and super-elasticity. Platinum–iridium microfilaments that are radiopaque improve visualization of the stent during deployment. Compared with the 48-strand Silk or Pipeline flow diverters, the larger TFD (≥3.5 mm) has more braided microfilaments, which decreases the shortening rate of the flow diverter after full opening and offers more appropriate pore attenuation. A design including a greater number of braided microfilaments is also seen in P64 diverter.

Therapeutic strategy for treating MCA aneurysms

In our center, microsurgical clipping is the preferred method for treating MCA aneurysms. Coiling or stent-assisted coiling is an alternative choice for elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, comatose patients with ruptured aneurysms, patients with recurrent aneurysms after previous clipping, and for patients with aneurysms deemed difficult to clip. However, fusiform aneurysms, recurrent aneurysms, and aneurysms with branches arising from the sac are difficult to treat with the aforementioned methods. For these aneurysms, treatment with an FDD has become a new option.

FDDs and MCA aneurysms

FDDs have become the first-line treatment for the ICA aneurysms, but not for MCA aneurysms because the mechanism of FDD healing the aneurysm is not consistent with the structure of MCA aneurysms. MCA aneurysms are mostly located at the MCA bifurcation and the bifurcating branches usually emanate directly from the base of the aneurysm. Landing the FDD in M1 and one trunk of M2 makes the other trunk of M2 “jailed.” The “jailed” branch might be occluded after FDD implantation, leading to cerebral ischemia. Conversely, if the “jailed” branch remained patent, the aneurysm might not be obliterated due to the persistent flow.15

Occlusion of the jailed branch

The long-term rate of side branch occlusion after coverage by a flow diverter in the treatment of ICA aneurysm was 15.8–20%.18,19 Beyond the Circle of Willis, 50% of covered branches were occluded or narrowed.20 Occlusion or reduced caliber of a jailed branch was seen in 14–50% cases of MCA aneurysms treated with a FDD and was one of the main causes of morbidity.16,17,21 In this study, there were seven aneurysms located at the M1 or MCA bifurcation, in which the bifurcating branches or lenticulostriate arteries emanated from the neck of the aneurysm or directly from the sac of the aneurysm. Immediate reduction of blood flow in these arteries was seen in two cases. During follow-up, the jailed branch was occluded or reduced in caliber in 42.9% (3/7) of the cases; however, there was no symptomatic cerebral ischemia noted in any patient.

About 5% of patients developed symptomatic cerebral ischemia caused by jailed artery occlusion or decreased flow.15 However, most patients tolerated jailed artery occlusion or decreased flow without symptoms or radiological findings.21 Gradual reduction of blood flow, instead of an abrupt change, occurred in most cases.14 Thus, the territories supplied by the jailed branch were able to recruit collateral vessels from adjacent branches over time.22

Occlusion of the aneurysm

The relatively low occlusion rate comparing to clipping was another reason why FDDs have not been used for the treatment of MCA aneurysms. The complete occlusion rate of FDDs in the treatment of MCA aneurysms was reported to be 36.4–84%.12–17 In this series, the complete occlusion rate was 37.5%, and favorable occlusion rate was 50%. The low complete occlusion rate might relate to three factors. First, persistent flow in the jailed branch might hinder thrombosis inside the aneurysm.15 The neck of the aneurysm usually involves more than 1 of the bifurcating branches. An FDD is usually deployed in one major branch and usually covers only part of the neck of the aneurysm. The uncovered part of the neck might have a persistent flow connection with the jailed branch, making it more difficult to initiate intra-aneurysmal thrombosis. As such, jailed branch occlusion could facilitate obliteration of the aneurysm.15 In case 1 in which the patient had an MCA bifurcation aneurysm, the jailed inferior trunk of M2 and the aneurysm were noted to be occluded on follow-up angiography. Second, in a curved vascular segment, the constituent filaments of the device slide over one another, making the porosity of the outer curve less than that of the inner curve, and thus less than the nominal porosity.23 This causes the flow diverting effect of the outer curve to decrease. In our series, six of eight aneurysms were located at the outer curve of the vessel, which may have contributed to the low complete occlusion rate. Third, the occlusion rate increases with the length of follow-up.24 Fifty percent of aneurysms are completely occluded no earlier than 12 months after surgery.12 In our study, only one aneurysm had angiographic follow-up of more than 12 months. Thus, the low complete occlusion rate may also be related to the relatively short follow-up period.

Six aneurysms in this study were fusiform, including one recurrent aneurysm. In case 1, we clipped and reconstructed the giant fusiform aneurysm. However, the aneurysm recurred in less than six months. In this aneurysm, the lesion might have involved the entire vessel wall, which may have allowed the unclipped part of the artery wall to enlarge and form another giant aneurysm. A flow diverter might be the optimal solution for this kind of aneurysm. Flow diversion might protect the vessel wall by both reducing the direct impact of the blood flow and inducing intra-aneurysmal thrombosis. However, unlike saccular aneurysm, the formation of neointima which may be crucial for minimizing the recurrence of the aneurysm, was not found in histological studies of fusiform aneurysms.25

In-stent stenosis

It is worth noting that although there were no delayed ischemic events, we found in-stent stenosis in 37.5% of the cases. Neointimal formation was necessary to cover the neck of aneurysm and block the inflow to aneurysm sac. However, overreaction of intimal hyperplasia might lead to in-stent stenosis. A possible reason for in-stent stenosis formation after flow diverter deployment is insufficient wall apposition, which might lead to thrombus in-between the stent mesh and arterial wall.26 One disadvantage of the TFD is that due to the nature of the nickel–titanium alloy, the visibility of the stent mesh is poor under fluoroscopy; only the two platinum–iridium radiopaque helix wires are highly visible. Therefore, it is sometimes difficult to assess wall apposition of the device. This may be a contributing factor to the high incidence of stent stenosis in this study. It has been reported that the rate of in-stent stenosis of flow diverters is as high as 57%.27 However, with longer follow-up in-stent stenosis might resolve spontaneously, and thus the rate will be lower.28,29

Limitations of the study

The limitations of this study are a relatively small number of patients, and a short follow-up period. However, the results of our preliminary experience of the treatment of complex MCA aneurysms using the TFD are encouraging. Patients with complex MCA aneurysms may benefit because of less procedure-related risk.

Conclusion

Our preliminary results demonstrated that the TFD is safe and effective for the treatment of MCA aneurysms. Given the high safety profile, the TFD could be a new option for the treatment of complex MCA aneurysms which are difficult to treat with clipping or coiling. However, further study with a larger population and long-term follow-up is needed to define the role of the TFD in the treatment of MCA aneurysms.

Contributors

FL, LL, BL, GZ, SO, and WX acquired the data. FL and YY analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. NG and TQ developed the project. All authors revised the paper critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. FL and YY contributed equally as first authors.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Department of Health of Guangdong Province (Grant number A2018067).

ORCID iD

Tiewei Qi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8435-6738

References

- 1.Alreshidi M, Cote DJ, Dasenbrock HH, et al. Coiling versus microsurgical clipping in the treatment of unruptured Middle cerebral artery aneurysms: a meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2018; 83: 879–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez-Hernandez A, Sughrue ME, Akhavan S, et al. Current management of middle cerebral artery aneurysms: surgical results with a “clip first” policy. Neurosurgery 2013; 72: 415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith TR, Cote DJ, Dasenbrock HH, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of endovascular coiling versus microsurgical clipping for unruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 2015; 84: 942–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kallmes DF, Hanel R, Lopes D, et al. International retrospective study of the pipeline embolization device: a multicenter aneurysm treatment study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 108–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadirvel R, Ding YH, Dai D, et al. Cellular mechanisms of aneurysm occlusion after treatment with a flow diverter. Radiology 2014; 270: 394–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iosif C, Ponsonnard S, Roussie A, et al. Jailed artery ostia modifications after flow-diverting stent deployment at arterial bifurcations: a scanning electron microscopy translational study. Neurosurgery 2016; 79: 473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu JM, Zhou Y, Li Y, et al. Parent artery reconstruction for large or giant cerebral aneurysms using the tubridge flow diverter: a multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial (PARAT). AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2018; 39: 807–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Y, Yang PF, Fang YB, et al. A novel flow-diverting device (tubridge) for the treatment of 28 large or giant intracranial aneurysms: a single-center experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 2326–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang YB, Wen WL, Yang PF, et al. Long-term outcome of tubridge flow diverter(S) in treating large vertebral artery dissecting aneurysms—a pilot study. Clin Neuroradiol 2017; 27: 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Kelly CJ, Krings T, Fiorella D, et al. A novel grading scale for the angiographic assessment of intracranial aneurysms treated using flow diverting stents. Interv Neuroradiol 2010; 16: 133–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.John S, Bain MD, Hui FK, et al. Long-term follow-up of in-stent stenosis after pipeline flow diversion treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2016; 78: 862–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briganti F, Delehaye L, Leone G, et al. Flow diverter device for the treatment of small middle cerebral artery aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanaty M, Chalouhi N, Tjoumakaris SI, et al. Flow diversion for complex middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Neuroradiology 2014; 56: 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yavuz K, Geyik S, Saatci I, et al. Endovascular treatment of middle cerebral artery aneurysms with flow modification with the use of the pipeline embolization device. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 529–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Topcuoglu OM, Akgul E, Daglioglu E, et al. Flow diversion in middle cerebral artery aneurysms: is it really an all-purpose treatment? World Neurosurg 2016; 87: 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhogal P, Martinez R, Gansladt O, et al. Management of unruptured saccular aneurysms of the M1 segment with flow diversion: a single centre experience. Clin Neuroradiol 2018; 28: 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhogal P, Almatter M, Bäzner H, et al. Flow diversion for the treatment of MCA bifurcation aneurysms—a single centre experience. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rangel-Castilla L, Munich SA, Jaleel N, et al. Patency of anterior circulation branch vessels after pipeline embolization: longer-term results from 82 aneurysm cases. J Neurosurg 2017; 126: 1064–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhogal P, Ganslandt O, Bäzner H, et al. The fate of side branches covered by flow diverters—results from 140 patients. World Neurosurg 2017; 103: 789–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schob S, Hoffmann KT, Richter C, et al. Flow diversion beyond the Circle of Willis: endovascular aneurysm treatment in peripheral cerebral arteries employing a novel low-profile flow diverting stent. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 1227–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cagnazzo F, Mantilla D, Lefevre PH, et al. Treatment of middle cerebral artery aneurysms with flow-diverter stents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017; 38: 2289–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lena J, Fargen KM. Flow diversion and middle cerebral artery aneurysms: is successful aneurysm occlusion dependent on branch occlusion? World Neurosurg 2016; 90: 630–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro M, Raz E, Becske T, et al. Variable porosity of the pipeline embolization device in straight and curved vessels: a guide for optimal deployment strategy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becske T, Brinjikji W, Potts MB, et al. Long-term clinical and angiographic outcomes following pipeline embolization device treatment of complex internal carotid artery aneurysms: five-year results of the pipeline for uncoilable or failed aneurysms trial. Neurosurgery 2017; 80: 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szikora I, Turányi E, Marosfoi M. Evolution of flow-diverter endothelialization and thrombus organization in giant fusiform aneurysms after flow diversion: a histopathologic study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 1716–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sindeev S, Prothmann S, Frolov S, et al. Intimal hyperplasia after aneurysm treatment by flow diversion. World Neurosurg 2019; 122: e577–e583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shankar JJ, Vandorpe R, Pickett G, et al. SILK flow diverter for treatment of intracranial aneurysms: initial experience and cost analysis. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5: i11–i15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Essbaiheen F, Alqahtani H, Almansoori TM, et al. Transient in-stent stenosis at mid-term angiographic follow-up in patients treated with SILK flow diverter stents: incidence, clinical significance and long-term follow-up. J NeuroIntervent Surg 2019; 11: 166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muhl-Benninghaus R, Haussmann A, Simgen A, et al. Transient in-stent stenosis: a common finding after flow diverter implantation. J NeuroIntervent Surg 2019; 11: 196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]