Abstract

White Americans who participate in the Black Lives Matter movement, men who attended the Women’s March, and people from the Global North who work to reduce poverty in the Global South—advantaged group members (sometimes referred to as allies) often engage in action for disadvantaged groups. Tensions can arise, however, over the inclusion of advantaged group members in these movements, which we argue can partly be explained by their motivations to participate. We propose that advantaged group members can be motivated to participate in these movements (a) to improve the status of the disadvantaged group, (b) on the condition that the status of their own group is maintained, (c) to meet their own personal needs, and (d) because this behavior aligns with their moral beliefs. We identify potential antecedents and behavioral outcomes associated with these motivations before describing the theoretical contribution our article makes to the psychological literature.

Keywords: social change, allies, motivations, collective action, protest

In 1963, William Lewis Moore, a White man from Baltimore, planned to walk from Chattanooga to Jackson in a protest against segregation. Moore believed that individuals can create social change by standing up for their convictions. During his journey, a store owner named Floyd Simpson (another White American) questioned Moore about his walk and he explained his views. Later that evening, Moore was shot and killed at close range with a rifle that belonged to Simpson. Although his murder was denounced by the President at the time, no one was ever indicted for this crime (Southern Poverty Law Center, n.d.).

In the example described above, Moore was an advantaged group member (a White American) engaging in an action (protesting segregation) that called for improvements in the treatment of a disadvantaged group (Black Americans).1 Other examples of action taken by advantaged group members for disadvantaged groups include heterosexual people who sign petitions urging the government to legalize same-sex marriage, men who attended the Women’s March, and people from the Global North who work to reduce poverty in the Global South. Due to the relatively recent interest in advantaged group members’ participation in action for the disadvantaged group within the psychological literature, the motives that underpin this behavior have been understudied (although see Edwards [2006] and Russell [2011]). Moreover, the research that does exist tends to represent advantaged group members who take action in support of the disadvantaged group as being motivated exclusively by a desire to improve the status or circumstances of the disadvantaged group, describing them as “allies” and their actions as allyship or ally behavior (Ashburn-Nardo, 2018; Broido, 2000; K. T. Brown, 2015; K. T. Brown & Ostrove, 2013; Ostrove & Brown, 2018).

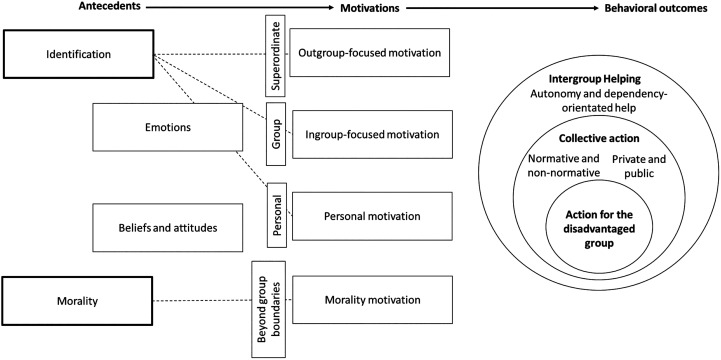

In this article, we go beyond the previous research on allyship to consider other reasons for why advantaged group members might be motivated to take action for disadvantaged groups. We describe four motivations (outgroup-focused, ingroup-focused, personal, and morality) and build on the extended social identity model of collective action (extended SIMCA; Van Zomeren et al., 2018) to frame the antecedents associated with each of these motivations. We then describe the behavioral outcomes associated with each of these motivations drawing on the intergroup helping (Nadler & Halabi, 2006), collective action (Wright et al., 1990), and allyship literatures (Droogendyk et al., 2016). We finish by detailing the contribution our work makes to the psychological literature and directions for future research.

Although there is a substantial corpus of research investigating disadvantaged group members’ participation in action to improve the status of their own group (see Van Zomeren et al., 2008; Wright, 2010 for reviews), far less attention has been paid to examining the participation of advantaged group members in these actions (e.g., Ashburn-Nardo, 2018; Becker, 2012; Droogendyk et al., 2016; Louis et al., 2019; Subašić et al., 2008; Thomas & McGarty, 2018; Van Zomeren et al., 2011). Although we do not want to imply that the participation of advantaged group members is necessary for social change to be achieved, there are a number of reasons why investigating the role of advantaged group members in political movements for social change is warranted. First, advantaged group members have been involved in historical and current political movements. For example, White Americans like Moore participated in the Civil Rights Movement, and heterosexual people have been involved in recent efforts to legalize same-sex marriage. Second, real and lasting social change often results from a shift in broader public opinion (David & Turner, 1996; Subašić et al., 2008) that prioritizes the rights of the disadvantaged group over maintaining the status and privilege of the advantaged group.

This shift in public opinion can be facilitated by advantaged group members. For example, Maass et al. (1982) found that conservative male participants were more supportive of abortion after discussing this topic with a liberal male confederate who was pro-choice compared with a liberal female confederate who was pro-choice. Furthermore, advantaged group members who confront prejudice may be perceived to be more effective at reducing prejudice than disadvantaged group members who engage in the same behavior (Cihangir et al., 2014; Czopp et al., 2006; Czopp & Monteith, 2003; Drury & Kaiser, 2014; Eliezer & Major, 2012; Gulker et al., 2013). For instance, Rasinski and Czopp (2010) had White participants watch a video in which a White speaker expressed discriminatory race-related comments and was confronted by either another White or a Black person. The confrontation by the White (compared with the Black) person was perceived to be more persuasive and lead to stronger perceptions that the person’s comments were biased.

However, the actions of advantaged group members may also become misguided. For example, Droogendyk and colleagues (2016) describe how, while participating in a political movement for the disadvantaged group, some advantaged group members make themselves the center of attention, act only when they have something to gain, fail to consider how disadvantaged group members are affected by their participation, push the disadvantaged group to include their voice in the movement, and expect that the disadvantaged group owes them something for supporting their cause. As a result, tension can arise over the inclusion and expectation of advantaged group members within movements that are led by disadvantaged groups. In our view, these misguided behaviors reveal that advantaged group members’ participation may be motivated by things other than a genuine interest in improving the status of the disadvantaged group.

The benefits and backlashes associated with involving advantaged group members in political movements may, in part, depend on their specific motivations for participating. We propose four primary categories of motivations: (a) outgroup-focused motivations, which reflect a genuine interest in improving the status of the disadvantaged group; (b) ingroup-focused motivations, which involve support for the disadvantaged group that is conditional upon maintaining the status of their own advantaged group; (c) personal motivations, which reflects a desire to benefit oneself and meet personal needs by engaging in action for the disadvantaged group; and (d) morality motivations, where action is primarily driven by moral beliefs and a resulting moral imperative to respond. Below, we describe these motivations in detail and consider potential predictors and behavioral outcomes associated with each. However, before doing so, we take a step back to define some key terms.

Defining Key Terms

Collective action was initially defined as action taken by a group member who is acting as a representative of their group with the goal of improving the conditions of their group (Wright et al., 1990). Collective action can include both public (e.g., participating in a protest) and private (e.g., signing an online petition) behaviors, and the term was originally used to describe action taken by disadvantaged group members (Van Zomeren et al., 2008; Wright et al., 1990). An advantaged group member who is acting for the disadvantaged is, by this definition, not taking part in collective action (they are not “acting as a representative of their group to improve the status of their group”). However, advantaged group members can participate in many of the relevant behaviors designed to advance the cause of the disadvantaged group, such as protesting, signing petitions, boycotting companies, and writing letters advocating for the disadvantaged group. In this article, we refer to these behaviors as action taken by the advantaged group for the disadvantaged group or action for the disadvantaged group for brevity.

Using this terminology acknowledges the original definition of collective action and allows us to consider a range of motivations for advantaged group members to participate in this behavior. It also allows us to theorize about how the motivations, through their antecedents and outcomes, can partly explain why tensions occur within political movements over the inclusion and expectation of advantaged group members. The decision to focus on behavior so that the motivations for these actions can be explored is not uncommon in the psychological literature. For example, see work examining motivations for people to volunteer (Clary & Snyder, 1999; Penner, 2002) and confront prejudice (Becker & Barreto, 2019; Munder et al., 2020). Using these terms also recognizes our discomfort with other terms used to describe action for the disadvantaged group (e.g., political solidarity, solidarity-based collective action; Leach et al., 2002; Saab et al., 2015; Subašić et al., 2008). These alternatives either do not include the intergroup context (e.g., social change, political action), or assumes that advantaged and disadvantaged group members always work together toward a common goal. The importance of these concerns will become evident when we start to explore the different motivations.

The reader might ask why we do not refer to all advantaged group members who act for the disadvantaged group as allies and the action they take as allyship or ally behavior. Allies are commonly defined as advantaged group members who “espouse egalitarian ideals” (Ashburn-Nardo, 2018), “relinquish social privileges conferred by their group status through their support for non-dominant groups” (K. T. Brown & Ostrove, 2013), “work to end oppression…through support of, and as an advocate with and for, the oppressed population,” and are “working to end the system of oppression that gives them greater privilege and power based on their social group membership” (Broido, 2000). We argue that not all advantaged group members who participate in action for the disadvantaged group are motivated for these reasons, and therefore cannot be called allies.2 For example, advantaged group members who are concerned with maintaining the status of their own group and/or participate in this behavior to meet their own personal needs do not fulfill the criteria described above for being an ally.

Theoretical Foundations for the Motivations, Antecedents, and Behavioral Outcomes

Like much of the social psychological literature on collective action, our theorizing about action for disadvantaged groups is grounded in the social identity approach (Subašić et al., 2008; Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987; Van Zomeren et al., 2008). This approach emerged from both self-categorization and social identities theories, and offers the critical insights that the self can be categorized at different levels of abstraction and thus both personal and collective identities can influence a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. As described below, this approach forms the theoretical foundation for the motivations, associated antecedents, and behavioral outcomes that are the focus of this article.

Self-categorization theory (Turner et al., 1987) proposes that we can represent ourselves at one of three levels of abstraction: the personal level (self as an individual), the collective level (self as a group member), or the superordinate level (self as part of a larger group which includes both ingroup and outgroup members). These levels of abstraction map onto the motivations for advantaged group members to engage in action for the disadvantaged group.

When self-categorization is at the level of the individual, it is characteristics that make one feel like a unique individual (what social identity theory describes as ones’ personal identity) that will guide our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Similarly, others are also seen and responded to in terms of their individual/personal identities. What we will describe as the personal motivation, where advantaged group members act to benefit their own self-interests and meet their personal needs, maps onto this level of self-representation.

When self-categorization is at the level of the group, our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are now guided by what social identity theory describes as our collective identity. At this level of categorization, the focus is on norms, values, and interests of the relevant ingroup and others are seen and responded to on the basis of whether they belong (ingroup members) or do not belong (outgroup members) to the same group. It is the psychology of these collective identities that maps onto what we will describe as the ingroup-focused motivation. Here, the interests and goals of the ingroup constrain advantaged group members to actions that will not disrupt the social hierarchy in such a way as to negatively affect the status of the ingroup.

Categorization at the level of a superordinate group can allow the individual to focus on the shared interests and goals of groups beyond their local ingroup. Self-representation at this higher level of abstraction maps onto the outgroup-focused motivation. Outgroup-focused advantaged group members seek to improve the circumstances and thus the status of the disadvantaged group and genuinely want to see change which grants more rights to the disadvantaged group. The outgroup-focused motivation might be associated with disidentification from the ingroup and instead identification with a new, shared identity with the disadvantaged group which works to achieve this goal.

Finally, a person can be motivated to act for the disadvantaged group for reasons that go beyond their personal and collective identities. If someone adopts a moral perspective, they are focused on what is right and what is wrong, because moral principles are perceived as universal and as transcending contextual boundaries (Hornsey et al., 2003, 2007; Skitka, 2010). As such, we propose a fourth motivation—the morality motivation—for advantaged group members to take action for the disadvantaged group. Morally motivated advantaged group members take action for the disadvantaged group because this behavior aligns with their moral beliefs such as avoiding harm. Although identification with a superordinate group can arise out of these moral beliefs—as we later discuss—they initially go beyond personal and group boundaries.

Note that we do not argue that these different levels of categorization when made salient in of themselves will give rise to the different motivations, or that those who act based on the different motivations will necessarily come to see themselves and others exclusively in terms of one particular level of identity. Rather, we use the idea of levels of identity as a theoretical framework to illustrate important distinctions between the four motivations. This point will become even more important when we later argue that the four motivations do not represent a typology of action for the disadvantaged group but rather can be held concurrently, and shift over time.

We also use the extended SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2018) as a theoretical framework when describing the antecedents for each motivation. The extended SIMCA uses the social identity approach to provide an integrated account of the predictors of collective action—identification, morality, emotions, and efficacy. The model proposes that group identification—particularly identification with a politicized group (such as a social movement which fights for the rights of a disadvantaged group)—and moral beliefs are core predictors of collective action. Collective action is further facilitated by feelings of anger about the perceived injustice the group experiences, and the belief that engaging in action will achieve the desired outcome. To provide a comprehensive account of the antecedents for the different motivations, we go beyond the extended SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2018) to consider the importance of several forms and targets of identification, other antecedent emotions (e.g., moral outrage, group-based guilt), and additional beliefs and attitudes such as privilege awareness and zero-sum beliefs. We, therefore, describe the antecedents of each motivation under the categories of identification, morality, emotions, as well as beliefs and attitudes. Note that not all categories of antecedents are relevant to each motivation. Identification is central to the outgroup-focused, ingroup-focused, and personal motivations, so we focus our attention on the role identification, in addition to emotions as well as beliefs and attitudes, plays when describing these motivations. Likewise, for the morality motivation, we concentrate on moral beliefs as an antecedent to this motivation and do not include an additional section on beliefs and attitudes because they are already covered by this antecedent.

In considering the behavioral outcomes associated with the motivations, we engage previous work that is grounded within the social identity approach (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987), including the needs-based model of helping (Nadler & Halabi, 2006) and the associated distinction between dependency- and autonomy-oriented help. We then turn to the collective action literature to examine whether the different motivations will result in a preference for normative and nonnormative as well as public and private collective action (Wright et al., 1990). And then we discuss the more recent literature on allyship to distinguish the different behavioral outcomes associated with each of the motivations (Droogendyk et al., 2016).

Finally, our discussion of the motivations should not be interpreted as a typology of advantaged group members themselves. We propose that some of the different motivations can coexist within a person, and may change over time and/or depending on the context in which they find themselves. We, therefore, describe advantaged group members who hold a certain motivation “to a greater extent” compared with the other motivations. Moreover, we are examining the differences in antecedents and outcomes of the different motivations among advantaged group member who participate in actions for the disadvantaged group, and not those who do not participate in these actions. The predictions we make in this article are therefore relative to the other motivations. See Table 1 for a summary of the antecedents and behavioral outcomes associated with the different motivation, and see Figure 1 for a diagrammatic representation of their relationship to one another.

Table 1.

Antecedents and Behavioral Outcomes Associated With Motivations for Advantaged Group Members to Engage in Action for the Disadvantaged Group.

| Motivations | Identification | Morality | Emotions | Beliefs and attitudes | Behavioral outcomes | Future research directions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outgroup-focused motivation | Lower ingroup identification Disidentification from the ingroup Identification with a superordinate politicized group (which includes, is in agreement with, and seeks to improve the status of the disadvantaged group) |

Group-based anger | Lower endorsement of negative stereotypes and prejudice toward the disadvantaged group coupled with higher privilege awareness |

Autonomy-oriented help Normative and nonnormative action (whichever best meets the needs of the disadvantaged group) Public and private action (whichever best meets the needs of the disadvantaged group) Behaviors which puts the needs of the disadvantaged group above that of the advantaged group |

Establish identification with a superordinate politicized group as the core predictor of the outgroup-focused motivation from which the other antecedents are derived |

|

| Ingroup-focused motivation |

Higher ingroup identification | Group-based guilt Sympathy for the disadvantaged group |

Zero-sum beliefs Paternalistic beliefs Social dominance orientation |

Dependency-oriented help More likely to engage in normative compared with nonnormative action More likely to engage in public compared with private action Behaviors which puts the needs of the advantaged group above that of the disadvantaged group |

Establish whether ingroup identification is the key driver for the ingroup-focused motivation Distinguish the role group–based guilt plays in preventing action for the disadvantaged group compared with taking action which is driven by the ingroup-focused motivation |

|

| Personal motivation | Higher personal identification |

|

Positive emotions such as joy and pride |

Individualism Narcissism |

Autonomy- and dependency-orientated help (whichever best meets the needs of the self) More likely to engage in normative compared with to nonnormative action More likely to engage in public compared private action Behaviors which puts the needs of the self above that of the disadvantaged group |

Establish the role personal identification plays in understanding this motivation (and the social identity approach more broadly) |

| Morality motivation |

Identification with a superordinate politicized group which develops from the moral beliefs that prompt action for the disadvantaged group | Moral beliefs about right and wrong which prompt action for the disadvantaged group | Moral outrage | Autonomy- and dependency-orientated help (whichever best aligns with the moral beliefs that prompt action) Normative and nonnormative action (whichever best aligns with the moral beliefs that prompt action) Public and private action (whichever best aligns with the moral beliefs that prompt action) Behaviors which puts the needs of the advantaged group above that of the disadvantaged group if the moral beliefs that prompt action align with egalitarian principles More likely to be involved in many different causes when compared with the outgroup-focused motivation |

Establish moral beliefs as the core predictor of the morality motivation from which the other antecedents are derived Examine the content of moral beliefs that are associated with action for the disadvantaged group that go beyond a violation of egalitarian principles |

Figure 1.

Motivations, their antecedents, and associated behavioral outcomes for advantaged group members to engage in action for the disadvantaged group.

Note. The bolded boxes indicate identification and morality as the core predictors of collective action described by the extended SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2018), and the dotted lines show the centrality of the category of antecedents for the different motivations. SIMCA = social identity model of collective action.

Outgroup-Focused Motivation

The extant work on allyship seems to hold as a given that advantaged group members are motivated to engage in action for the disadvantaged group because they have a genuine interest in improving the status of the disadvantaged group. Examples of this motivation include men who are willing to take a pay cut to raise the salaries of women so that women are paid the same as men for the same work; Europeans assisting refugees to safely cross the Mediterranean because they want them to have a safer life; and wealthy people endorsing tax reforms to improve the lives of those living in poverty by increasing taxes for the rich and middle class. This is consistent with the common definition for allies found in the psychological literature (e.g., Ashburn-Nardo, 2018; Broido, 2000; K. T. Brown, 2015; K. T. Brown & Ostrove, 2013; Ostrove & Brown, 2018), which include the genuine motivation to improve the status of the disadvantaged group. We describe the antecedents of this motivation using the predictors delineated by the extended SIMCA (identification, emotions, beliefs, and attitudes; Van Zomeren et al., 2018).

Identification

Based on the social identity approach, lower identification with one’s advantaged ingroup should predict the outgroup-focused motivation. According to social identity theory, people are motivated to see the groups they identify within a positive light (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Thus, in order for advantaged group members to be willing to put the needs of the outgroup above those of their own group or to criticize or even abandon the interests of the ingroup, they are likely to be less identified with their ingroup.

Consistent with this argument, Ellemers et al. (1997) found that participants with low (compared with high) identification with an assigned group felt less committed to the group and more interested in leaving that group. This was true regardless of the status of the group. Other research has found that White Americans who identified less with their racial group were more likely to support affirmative action policies for Black Americans (Lowery et al., 2006). This claim is also consistent with work on disidentification.

Disidentification describes when individuals psychologically distancing themselves from an ingroup they wish they did not belong to. Becker and Tausch (2014) found that individuals who disidentify do not engage in ingroup helping behaviors and are likely to actively and passively harm their own group. This suggests that those who disidentify from their advantaged ingroup would be free of the usual motivation to maintain the status of their ingroup (Jost et al., 2004; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999; Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and thus would be more easily motivated to focus on the outgroup.

Furthermore, stronger identification with a larger superordinate group that includes the disadvantaged group could also strengthen the outgroup-focused motivation. The common ingroup identity model (e.g., Gaertner et al., 1993) describes the process through which members of two groups (e.g., Black and White Americans) come to see themselves as members of a single larger ingroup (e.g., Americans). One result of this recategorization process is a reduction in intergroup bias and an increase in prosocial behavior toward those who were previously outgroup members. For example, Vezzali et al. (2015) found that the extent to which Italian and immigrant children perceived a recent earthquake in Italy to be threatening was associated with them feeling like they belonged to the common group “children” (which included both in and outgroup members). These feeling of being part of a common group predicted greater willingness to help victims of the natural disaster from the outgroup (see also Dovidio et al., 1997). Thus, it may be that advantaged group members who see advantaged and disadvantaged group members as part of a larger common ingroup, and who identify with this larger superordinate group, will be motivated to participate in actions that benefit the outgroup.

However, caution is warranted when using this approach to encourage action for the disadvantaged group. The creation of a common ingroup identity can conceal important real world differences between the advantaged and disadvantaged (Cole, 2009; Crenshaw, 1991; Ostrove et al., 2009), and can lead to the diluting or even undermining of the original goal of collective action defined by the disadvantaged group (Banfield & Dovidio, 2013; Droogendyk et al., 2016; Saguy et al., 2009). One potential solution to this problem can be found in the specifics of the normative beliefs and values of the particular superordinate category. For example, holding a politicized identity (i.e., identifying with a social movement; Simon & Klandermans, 2001; Stürmer & Simon, 2004; Van Zomeren et al., 2008) may be a key antecedent of the outgroup-focused motivation, because the content of this identity includes group norms and beliefs that are geared toward improving the status of the disadvantaged group. For instance, someone who identifies as a feminist endorses gender equality beliefs which motivates them to improve women’s status (Becker & Wagner, 2009). Previous research has found that politicized identification predicts collective action among advantaged group members for the disadvantaged group (Subašić et al., 2008; Van Zomeren et al., 2011).

Given that both advantaged and disadvantaged group members can identify with a politicized identity—making this a superordinate identity—and that the content of this identity fundamentally seeks to improve the status of the disadvantaged group, we propose that higher identification with a politicized group will be associated with the outgroup-focused motivation. This argument is in line with the extended SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2018) where identification with a politicized group is positioned as a core predictor of collective action from which the other predictors are derived. Moreover, according to the politicized solidarity model of social change (Subašić et al., 2008), identification with a politicized group might reflect a shift in advantaged group members’ self-categorization from identifying with those in power who are responsible for the mistreatment of the disadvantaged group, to a categorization which aligns with the interests of the disadvantaged group, but excludes the authorities and powerholders. This identity could also be formed based on the opinions advantaged group members share with the disadvantaged group (i.e., opinion-based groups; Bliuc et al., 2007; McGarty et al., 2009). What is of importance here is the content of the politicized identity centers around improving the status of the disadvantaged group which both includes—and is in agreement with—the disadvantaged group. These politicized group identities do not blur the boundaries between advantaged and disadvantaged groups, and thus may be able to avoid some of the pitfalls associated with simply identifying with any common ingroup. Instead, these politicized superordinate groups make the outcomes and the status of the disadvantaged group relevant to the advantaged group (see L. G. Smith et al., 2018, for an example).

Emotions

The extended SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2018) describes how emotions—particularly group-based anger—are relevant to understanding why someone would engage in collective action. Group-based anger describes the collective feeling of anger people experience when they perceive that a social group is being treated unfairly (Van Zomeren et al., 2004, 2008) and can be directed at the authorities and powerholders, as well as other members of the advantaged group who engage in discrimination against the disadvantaged group (Leach et al., 2006; Subašić et al., 2008). Previous research has found that group-based anger predicts action for the disadvantaged group among both disadvantaged (Van Zomeren et al., 2008) and advantaged group members. For example, previous research has found that group-based anger about the discrimination Muslims experience predicted intentions for non-Muslim participants to take action for the outgroup (Van Zomeren et al., 2011).

We propose that group-based anger is an antecedent of the outgroup-focused motivation. We argue that group-based anger is particularly relevant to the outgroup-focused motivation, because it is an action-oriented emotion (Leach et al., 2006) which seeks to achieve social change (Thomas et al., 2009a; see also Leach et al., 2006) and is driven by comparisons and experiences between and within groups (Mackie et al., 2000; Runciman, 1966; H. J. Smith & Ortiz, 2002; Stouffer et al., 1949). This drive for social change is embedded within the goal of this motivation—to improve the status of the disadvantaged group—which unlike the other motivations is initiated and bound by membership in a superordinate group that includes the disadvantaged group and is shaped by a politicized identity.

Beliefs and Attitudes

The extended SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2018) also describes the role group efficacy plays as a predictor of collective action. People are more likely to participate in collective action when they believe it will help achieve their group’s goals (Hornsey et al., 2006; Kelly & Breinlinger, 1995). In this model, group efficacy is described as a predictor of collective action which distinguishes between those who take action and those who do not. We choose to extend this category of antecedents beyond group efficacy to other beliefs and attitudes that might motivate action for the disadvantaged group to provide a more comprehensive account of the different motivations.

We expect that this motivation will be preceded by lower endorsement of negative stereotypes about, and lower prejudice toward the disadvantaged group (Ashburn-Nardo, 2018; Ostrove & Brown, 2018). We argue, however, that this is not enough to facilitate action which is driven by the outgroup-focused motivation. As K. T. Brown and Ostrove (2013) state, “Allies can be distinguished from individuals who are motivated simply to express minimal or no prejudice toward nondominant people. Allies are people willing to take action, either interpersonally or in larger social settings, and move beyond self-regulation of prejudice.” We propose that what distinguishes the outgroup-focused motivation from people who are just low in prejudice and stereotyping toward the disadvantaged group is higher levels of privilege awareness.

Privilege refers to the “automatic unearned benefits bestowed upon perceived members of dominant groups based on social identity” (Case et al., 2012; McIntosh, 1989), and while there is considerable discussion about the ways in which members of privileged group members can remain blind to these unearned benefits (see Johnson, 2017), advantaged group members can vary in the degree to which they are aware of these privileges. We propose that advantaged group members who are higher in awareness of their own privilege will be more focused on the needs and interests of the outgroup, as they will be more likely to see how their privileges lead to the oppression of the disadvantaged group. Previous research has found that privilege awareness is associated with support for affirmative action. Affirmative action involves an organization devoting resources (including time and money) to proactively prevent discrimination against people who belong to disadvantaged groups (Crosby & Cordova, 1996; Crosby et al., 2006). Swim and Miller (1999) found that, across a number of studies, higher awareness of White privilege among White participants predicted support for affirmative action for Blacks. Likewise, other research has found that university students who took part in a semester-long course about diversity increased in their awareness of male and White privilege, and this was associated with greater support for affirmative action for women and people of color (Case, 2007a, 2007b). These behaviors can include active recruitment of women and minorities, monitoring hiring practices to ensure that they do not reduce the chances that qualified women and minority candidates are hired, building mentoring programs for female and minority students, and eliminating discriminatory structures in an organization. Given that affirmative action seeks to improve the status of the disadvantaged group, we can use this research as evidence for the outgroup-focused motivation.

Thus, higher awareness of the privileges afforded to the advantaged group appears to have a direct effect on one’s interest in serving the needs of those who are oppressed. However, this effect of privilege awareness could also be further accentuated by its effect on identification with and even disidentification from the privileged ingroup. Powell and colleagues (2005) provide some evidence for this possibility. They encouraged White American participants to think about the inequalities between White and Black Americans using one of two different framings. Those who were encouraged to focus on the privileges afforded to White people (the White privilege framing) reported lower White racial identification than those encouraged to focus on the disadvantages experienced by Black people (the Black disadvantaged framing). As described earlier, lower ingroup identification and disidentification with the ingroup can free up advantaged group members to focus on the needs of the outgroup. Thus, awareness of ingroup privilege should have both direct and indirect positive effects on the outgroup-focused motivation.

Summary

Some advantaged group members who engage in action for the disadvantaged group may genuinely seek to improve the status of the disadvantaged group. This is consistent with the common definition for allies found in the psychological literature (e.g., Ashburn-Nardo, 2018; Broido, 2000; K. T. Brown, 2015; K. T. Brown & Ostrove, 2013; Ostrove & Brown, 2018). We proposed that this motivation emerges from a set of antecedents that match nicely with some of the predictors considered in the extended SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2018). In short, we expect that the antecedents of this motivation will include: lower identification with or even disidentification from the advantaged ingroup; identification with a politicized group that endorse norms and beliefs associated with fighting for the rights of the disadvantaged group; feelings of group-based anger toward the authorities and those who engage in discrimination; rejection of negative stereotypes and prejudicial attitudes about the disadvantaged group; and higher privilege awareness. It is advantaged group members with this profile who are most likely to be propelled toward the sometimes uncomfortable and difficult work required to improve the status of the disadvantaged group.

Ingroup-Focused Motivation

Advantaged group members’ motivation to engage in action for the disadvantaged group can also be influenced by their concern for the interests of their own advantaged ingroup. We propose that the ingroup-focused motivation exists along a continuum. At one end of this continuum, where advantaged group members also feel some connection with and concern for the disadvantaged group, they might be happy to do whatever is needed to improve the status of the disadvantaged group so long as the current hierarchy which advantages their ingroup remains. For instance, men might be willing to participate in a Reclaim the Night protest against the violence that women experience, but may not be willing to advocate for equal pay for women in the workplace. The first action might be truly outgroup-focused—motivated by a genuine concern for the safety of women. However, men who are also focused on the ingroup may draw a line when their action for women may reduce the relative economic and political status of their own group, such as advocating for legislation that requires women to be paid the same as men for the same type of work. Thus, these advantaged group members who remain focused on ingroup concerns will appear quite inconsistent. At times, their behavior will resemble those driven by the outgroup-focused motivation, but because their support is constrained by their motivation to maintain the status of their own group, at other times they will appear unconcerned about the needs of the disadvantaged group.

At the other end of the continuum, in the more sinister case, advantaged group members who engage in behaviors that ostensibly seek to improve the status of the disadvantaged group but ultimately result in benefits for, and enhance the status of, their own group. For instance, when the German Chancellor Angela Merkel changed her position on whether a vote should be held for same-sex marriage in 2017, this triggered a conscience vote in the Bundestag leading to the legalization of same-sex marriage. Although her initial actions substantially improved the status of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and questioning or queer (LGBTIQ) community in Germany, her decision to vote against the legislation (to appeal to her conservative constituents) and to hold the vote just months before the general election (taking off the table a key campaign issue that leftist parties hoped to secure more votes over) suggest that her actions were driven not by a genuine interest in improving the situation for the LGBTIQ community, but by a desire to maintain the status of her political party (which went on to lead the grand coalition later that year). This ingroup-focused motivation also aligns with theorizing surrounding motivations to help outgroup members (Van Leeuwen & Täuber, 2010). The researchers propose that one motivation for helping outgroup members is to maintain the power and autonomy of one’s own group.

Identification

We propose that higher ingroup identification is a primary antecedent of the ingroup-focused motivation. The social identity approach has at its core the premise that ingroup identification is essential for positive ingroup-directed thoughts (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), and the link between ingroup identification and ingroup-serving behavior is well established (R. Brown, 2000; Hornsey, 2008). Thus, highly identified advantaged group members should be more likely to be conscious of the concerns of the ingroup, even as they may be acting for the disadvantaged group.

Research illustrates that ingroup identity can be enhanced or restored by helping an outgroup (e.g., Van Leeuwen, 2007). Using a minimal group paradigm, Nadler and colleagues (2009) randomly assigned participants to two groups ostensibly on the basis of their performance on a test, and their level of identification was manipulated by informing participants that they were either a typical or atypical member of their assigned group. To manipulate perceived threat to group status the participants were told that their group did better or worse than the other group in a test of “integrative thinking.” They were then asked to complete a task with members of the other group, and the researchers measured the amount of assistance they offered them. Participants provided the most amount of help when they were highly identified with their ingroup and perceived that the outgroup was a threat to their group’s status. This suggests that highly identified advantaged group members might be motivated to engage in actions for the disadvantaged group when they feel their ingroup is being threatened as a way to maintain the status of their advantaged ingroup. Further support for this finding comes from the work by Scheepers (2009; Scheepers et al., 2009) which found that when members of a high-status group were told that the advantaged position of their ingroup was unstable and likely to change, they had physiological responses (higher blood and pulse pressure) indicative of them feeling that their social identity was being threatened. Given that advantaged group members are motivated to maintain the status quo—and the participants felt threatened when they were told this can change—we would expect these findings to be particularly relevant to high-identifying group members.

Advantaged group members can also act for the disadvantaged group because they want their group to be seen in a positive (Teixeira et al., 2019) and moral light (Becker et al., 2018), to communicate warmth when presented with negative stereotypes about their group (Hopkins et al., 2007; Van Leeuwen & Täuber, 2012), and to boost the reputation of their group by displaying their knowledge (Van Leeuwen & Täuber, 2010). We argue that these reasons for helping the outgroup are driven by the need to maintain, protect, and bolster the status of the ingroup (i.e., the ingroup-focused motivation) and that these needs will be felt most acutely by high identifiers.

Emotions

We propose that two group-based emotions, group-based guilt and sympathy, will be strong predictors of the ingroup-focused motivation. Group-based guilt (often referred to as collective guilt or White guilt in the context of race-relations; for example, Wohl et al., 2006) is an ingroup-focused emotion invoked when the advantaged ingroup feels responsible for the treatment of the disadvantaged group (Iyer et al., 2003; Iyer & Leach, 2008; Montada & Schneider, 1989; Schmitt et al., 2000).

Previous research has found that guilt can motivate advantaged group members to engage in action for the disadvantaged group. For example, Mallett et al. (2008) found that the extent to which White participants took the perspective of Black Americans who experienced a hate crime, the more they experienced White guilt and this higher level of guilt predicted their intentions to engage in action for Black Americans. However, other research has found that group-based guilt promotes behaviors that reduce the negative experience of this emotion through restitution or avoidance, rather than through action that will genuinely improve the situation for the disadvantaged group (Iyer et al., 2003, 2004, 2007; Leach et al., 2006; McGarty et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 2009b). As a result, group-based guilt can stymie action for the disadvantaged group (e.g., Harth et al., 2008) and maintains group boundaries that privilege the advantaged group (Reicher et al., 2006; Thomas et al., 2009b).

We propose that group-based guilt motivates action that acknowledges the lower status of the disadvantaged group and seeks to provide restitution that does not threaten the higher status of the advantaged group (such as attending a demonstration acknowledging that hate crimes are unacceptable). Moreover, while the decision to take action will be motivated by the quickest and easiest way to reduce this negative emotional state, in the group context, restoring the tarnished moral image of the advantaged group (which may be the driving force behind this negative emotional experience) is perhaps more important. For example, Roccas et al. (2006) found that higher attachment to the ingroup (commitment to the group and inclusion of the group in one’s self-concept) was associated with higher group-based guilt, because high identifying group members become distressed when they perceive that their ingroup deviates from group-level moral standards. Given that high identifiers are also the ones most focused on maintaining the status of the ingroup, we expect that group-based guilt will be an important antecedent of the ingroup-focused motivation to engage in action for the disadvantaged group.

At the group-level, sympathy is conceptualized as an other-focused emotion that recognizes the plight of the disadvantaged group and perceives the disadvantage they experience to be illegitimate but unlikely to change (Harth et al., 2008; Leach et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2009b). It can be argued that sympathy is distinct from empathy because sympathy maintains group boundaries between the advantaged and disadvantaged groups—the advantaged group feels sympathy for the disadvantaged group, not empathy with the disadvantaged group (Davis, 2004). In addition, empathy is often theorized to include cognitive processes like perspective taking, which require someone to put themselves in the shoes of another, whereas sympathy is understood to be primarily affective/emotional (Wispé, 1986).

Previous research has found that sympathy can predict action among advantaged group members for the disadvantaged group (Harth et al., 2008; Iyer et al., 2003; Tarrant et al., 2009), but there is evidence to suggest that this emotion is constrained by the need to maintain the status of the advantaged group as described by the ingroup-focused motivation. Sympathy maintains group boundaries which prevents the formation of a politicized identity which we argue is a necessary precursor for action that seeks to improve the status of the disadvantaged group. For example, Subašić and colleagues (2008) propose that advantaged group members who support the disadvantaged group but are unwilling to challenge powerholders to improve the status of the disadvantaged group may sympathize with the plight of the disadvantaged group but this does not lead to social change. As Thomas and colleagues (2009b) state, “Put another way, they ‘feel sorry for them’ but are simultaneously committed to maintaining the status quo.” Feeling sympathetic toward the disadvantaged group is also theorized to prompt dependency-oriented help (Thomas et al., 2009b)—a type of help that makes the disadvantaged group dependent on the advantaged group, and in doing so, does not challenge the status quo (Nadler & Halabi, 2006).

Beliefs and Attitudes

The ingroup-focused motivation should also be inspired by zero-sum beliefs, paternalism, and social dominance orientation (SDO). Zero-sum beliefs refer to the perception that when something is achieved for one person, another person will experience a proportional loss as a result (Nash, 1950). Applied to the intergroup context, one example of this would be the belief that when discrimination against the disadvantaged group decreases this results in a proportional increase in discrimination against the advantaged group (Kehn & Ruthig, 2013; Norton & Sommers, 2011; Ruthig et al., 2017; Wilkins et al., 2015).

Previous research has found that men who believe that actions which improve the rights of women will result in fewer rights for men are more likely to take action that undermines women’s pursuit of gender equality. For example, Radke et al. (2018) examined the intentions for men to respond to the problem of violence against women. They contrasted interest in action which would directly confront violence against women (e.g., protesting) with support for actions that would protect individual women from male violence (e.g., sponsoring women to attend a self-defense class so that they can learn how to protect themselves). They found that men who more strongly endorsed zero-sum beliefs about women’s rights showed a preference for actions which protected individual women from male violence rather than actions that directly confronted the problem and identified ways in which male violence can be reduced. In other words, stronger zero-sum beliefs among men were associated with actions that support women but ultimately maintain men’s higher status (see also Brownhalls et al., in press). Based on these findings, we expect that zero-sum beliefs will predict the ingroup-focused motivation among advantaged group members who participate in action for the disadvantaged group.

A desire to help and protect the disadvantaged group may also be driven by paternalistic beliefs which are associated with support for the disadvantaged group so long as the advantaged group takes care of and provides for them (Jackman, 1994). Action for the disadvantaged group can be one way that advantaged group members can display these paternalistic beliefs. Support for this argument comes from research which found that paternalistic beliefs predict German’s willingness to provide dependency-oriented help to refugees (Becker et al., 2018). Dependency-oriented help maintains the lower status of the disadvantaged group by making them dependent on the help provided by the advantaged group. Thus, paternalistic beliefs motivate action by the advantaged group that, while helpful to the disadvantaged, is also motivated by an interest in, and commitment to, the superior status of the advantaged ingroup.

Advantaged group members with higher levels of SDO are also more likely to provide dependency-oriented help to disadvantaged group members when they feel that the status of their group is being threatened (Halabi et al., 2008). SDO is a “general attitudinal orientation toward intergroup relations, reflecting whether one generally prefers such relations to be equal, versus hierarchical” (Pratto et al., 1994, p. 742). In other words, those high in SDO generally prefer and support group–based inequality, and thus, advantaged group members who are high in SDO should be motivated to help the disadvantaged group only to the extent that the higher status of their own group is reinforced and maintained. Relevant to our argument here, levels of SDO can be impacted by perceived group status and the context in which these groups are situated (Levin, 2004; Radke, Hornsey, Sibley, Thai, & Barlow, 2017). Evidence of SDO as an antecedent for the ingroup-focused motivation includes research on gender where SDO is positively correlated with benevolent sexism, a seemingly positive form of prejudice which seeks to protect women but ultimately maintains their lower status position in society by restricting them to stereotypical and traditional gender roles (Christopher & Mull, 2006; Christopher & Wojda, 2008; Fraser et al., 2015; Kteily et al., 2012; Radke, Hornsey, Sibley, & Barlow, 2017; Sibley & Overall, 2011; see Jackman 1994 for a description of this broader theoretical argument). Furthermore, Radke and colleagues (2018) recently established a connection between men’s endorsement of benevolent sexism and their preference to take part in action which protects women from male violence rather than actions that more broadly and directly challenges male dominance and violence.

Summary

We believe it is valuable to recognize that advantaged group members might be motivated to participate in action for the disadvantaged group at the same time maintaining a strong focus on the needs and interests of their own advantaged ingroup. Thus, they may seek actions that benefit the disadvantaged group on the condition that the status of their own group is maintained. Alternatively, and more malevolently, they could engage in actions which on the surface appear to support the disadvantaged group, but in reality seek to bolster the status of the advantaged group. We propose that this kind of ingroup-focused motivation is underpinned by higher ingroup identification; the emotions of group-based guilt and sympathy; and specific beliefs and attitudes such as zero-sum beliefs, paternalism, and SDO that maintain the higher status of the advantaged group.

Personal Motivation

Advantaged group members’ engagement in action for the disadvantaged group can also be motivated by personal self-interest—actions that seek to meet personal needs and/or accrue personal benefits. We ground our reasoning in the literature on collective action among disadvantaged groups, which also recognizes that participation in collective action may be motivated by personal concerns (Klandermans, 1984; Stürmer & Simon, 2004; Van Zomeren & Spears, 2009). According to Van Zomeren and Spears (2009), some individuals are motivated to engage in collective action only when the individual benefits of taking action outweigh the individual costs (the researchers referred to these people as “intuitive economists”; a metaphor used by Tetlock, 2002). Similarly, Klandermans (1984; see also Stürmer & Simon, 2004) identified three cost-benefit motives for collective action. These include the collective motive (concern for the collective benefits the social movement fights for), the normative motive (concern for whether others will approve or disapprove of the collective action), and the reward motive (concern for the personal costs and benefits associated with engaging in collective action).

This theorizing can also be applied to advantaged group members, where individuals calculate the personal costs and benefits (described by the intuitive economist approach as well as the normative and reward motive) of engaging in action for the disadvantaged group before doing so. Although a focus on personal self-interest provides obvious explanations for why advantaged group members will be motivated to not act for the disadvantaged group, we propose that at times a concern for one’s own personal outcomes can also motivate action for the disadvantaged group.

We propose that advantaged group members who act for the disadvantaged may do so to improve their reputation, gain popularity, increase opportunities to make money, or, in the case of politicians, increase the likelihood of being elected. A 2017 Pepsi advertisement starring Kendall Jenner provides an interesting, although perhaps failed, example of this. In it Jenner joins what appears to be protest that is facing off against a line of police officers before giving a can of Pepsi to a police officer as a peace offering. The advertisement was largely criticized for being tone-deaf and co-opting the Black Lives Matter movement (especially given the parallels between Jenner’s actions in the advertisement and a photo taken of Iesha Evans, a Black Lives Matter protester who was arrested after approaching police; Sidahmed, 2016). It is not difficult to imagine that Pepsi was seeking to improve their brand’s reputation, popularity, and make money by attempting to show solidarity with those participating in political movements. We further suggest that there are many less obvious examples where advantaged group members get involved in political action, in part to maintain or increase their personal popularity among a diverse friendship group, or where wealthy individuals seek to become the face of charitable campaigns to have themselves associated with the positive outcomes the charities produce.

Identification

The social identity approach (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987) argues that people hold both personal and collective identities—the latter being extensively studied within the social identity approach to understand group behavior while the former not receiving as much attention within this theoretical framework. If an advantaged group member does not identify strongly with their ingroup or with a superordinate group which includes the disadvantaged group, their participation in action for the disadvantaged group might result from a focus on potential personal benefits and higher levels of personal identification (i.e., identification with the personal self).3 For instance, Simon et al. (2000) found that higher personal identification among heterosexual individuals predicted their intentions to volunteer with AIDS patients, in contrast to gay people for whom collective identification was a significant predictor. The authors concluded that heterosexual individuals construed their volunteering as an interindividual helping situation. Thus, fulfilling personal identity needs—preceded by higher identification with the personal self—may motivate advantaged group members to act for the disadvantaged group. Importantly, we continue to place identification at the core of this motivation which is in some sense consistent with Van Zomeren and colleagues’ (2018) extended SIMCA—the theoretical frameworks that we have used to describe the antecedents of action for the disadvantaged group. However, by pursuing the role that personal identification plays, we move beyond this model, which focuses almost exclusively on collective identification, and offer a novel direction for future research which might also benefit the social identity approach more broadly.

Emotions

Research on volunteerism has also found that positive emotions, such as pride and joy, can motivate long-term commitment to organizations (Jiménez & Fuertes, 2005), and positive feelings more generally can motivate helping behavior (Cunningham, 1979; Isen & Levin, 1972). When people feel positive emotions, such as happiness, they are more likely to focus on others (Seligman, 2002), and the propensity to feel authentic pride and gratitude predicts intentions to engage in social justice behaviors (Michie, 2009). However, there is also reasons to wonder whether advantaged group members for whom experiencing personal positive emotions is a key motivation for getting involved may have trouble sustaining their engagement. Action for social change requires long term commitment that may often be experienced as stressful rather than joyful. Thus, their action will likely waiver when the positive feelings that provide personal benefits cannot be maintained.

Beliefs and Attitudes

Given the focus on personal identification, we propose that advantaged group members motivated for personal reasons might also be higher on measures of individualism and perhaps even narcissism. Individualism is often situated as the opposite of collectivism, and is a worldview characterized by concern for the self, a desire to attain personal goals, emphasis on individual uniqueness, and the role of personal control which minimizes social influences (Oyserman et al., 2002). If someone adheres to this worldview, then they may be motivated to act for the disadvantaged group if this behavior helps them achieve the personal outcomes described by the personal motivation.

Narcissism, on the other hand, is broadly defined as a grandiose sense of self which is fueled by a sense of entitlement (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Previous research has found that the grandiose exhibitionism subscale of the narcissistic personality inventory predicts self-promoting behaviors (Carpenter, 2012). These behaviors are presumably motivated by the personal rewards of improved reputation and popularity, something we theorize advantaged group members motivated for personal reasons might seek.

Summary

In this section, we propose that advantaged group members can be motivated to engage in action for the disadvantaged group to meet personal needs and accrue personal benefits. We propose that the antecedents of the personal motivation include higher personal identification, positive emotions such as pride and joy, as well as the endorsement of an ideology of individualism and the personal self-aggrandizing beliefs and self-focused attention associated with narcissism.

Morality Motivation

Finally, engaging in action for a disadvantaged group may at times result from advantaged group members’ motivation to act in accordance with their moral beliefs about what is right and wrong—to enact their values and adhere to higher order principles. The extended SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2018) argues that moral beliefs are a key predictor of collective action. We propose that they may also be a central motivation for some advantaged group members who engage in action for the disadvantaged group.

Morality

Discussions of morality propose that social interactions are governed by a set of key basic moral principles, such as harm avoidance or fairness (e.g., Graham & Haidt, 2012; Gray et al., 2012), and that behaviors that violate these principles arouse strong emotional reactions and motivate action. Skitka (2010) argued that

when people take a moral perspective, they focus more on their ideals, and the way they personally believe things “ought” or “should” be done, than on a duty to comply with authorities or to conform to group norms. In short, moral concerns originate more from autonomous concerns than they do concerns about authorities or group identities. (see also Hornsey et al., 2003, 2007)

In other words, if an act is perceived as fundamentally morally wrong, local group norms and even societal laws will be of little importance, because moral principles are perceived as universal and as transcending any contextual boundaries. Consequently, moral beliefs about right and wrong are considered to go beyond individual and/or group boundaries, and may motivate people to act for others with whom they may not share anything in common (Skitka, 2010; Turiel, 2002; Van Zomeren et al., 2011). From this perspective, if the treatment of disadvantaged group members is perceived by some advantaged group members as a violation of a basic moral principle, it may make participating in action for the disadvantaged group a moral imperative.

Theoretical and empirical work on values, moral intuitions, and moral convictions point to several moral beliefs that may lead advantaged group members to act for the disadvantaged group. For instance, Schwartz’s (1992) theory of basic human values suggests that the value of universalism is concerned with understanding, appreciating, tolerating, and protecting the welfare of all people regardless of what group they belong to (Schwartz, 1992, 2007). Several cross-national studies have found that universalism positively predicts moral concern for all members of society, acceptance, and the perceived positive consequences of immigration, as well as political activism for social justice issues and the environment (Schwartz, 2007, 2010; see also Gärling, 1999; Tartakovsky & Walsh, 2016).

Moreover, having a strong moral stance on equality and endorsing egalitarian values motivates people to confront prejudice (e.g., Monteith & Walters, 1998), and research has found that moral conviction against social inequality is a predictor of action for the disadvantaged group. For example, Van Zomeren and colleagues (2011; Study 1) found that non-Muslim participants who had a strong moral conviction against social inequality reported greater willingness to engage in action for Muslim people to reduce the discrimination they experience. Russell (2011) also found that heterosexual allies take action for LGBTIQ rights because doing so is in line with their fundamental principles of justice and civil rights. Similarly, Simon and colleagues (2000) found that volunteerism for gay men who had an AIDS diagnosis was predicted by humanitarian values among heterosexuals. Kende and colleagues (2017) found that advantaged group members for whom refugee rights were part of their core moral beliefs were more likely to engage in volunteering and action for this group.

Harm avoidance is also found to be a universal moral belief that focuses people on the suffering of others (Graham et al., 2009; Gray et al., 2012; Haidt & Joseph, 2004; Schein & Gray, 2018). For instance, a recent analysis of tweets about the refugee crisis indicated that posting about the death of a refugee child (i.e., Aylan Kurdi), a highly harmful event, predicted more solidarity with refugees at a later time (L. G. Smith et al., 2018). Moreover, the authors suggested that the posts were not only shared by those with already formed pro-refugee opinions but also by those who were presumably less involved in the issue.

Evident from the discussion above, the psychological literature has largely focused on the violation of egalitarian principles as a pathway to action for the disadvantaged group. However, this need not necessarily be the case. People can hold moral beliefs for a range of different principles—such as against harm, loyalty, purity, and a moral obligation to protect—which when violated can motivate action for the disadvantaged group. For example, men might be motivated to take action for women against violent pornography which demeans women because this violates their moral belief in social equality (leading them to demand social change for the rights of women) or because this violates their moral beliefs that women should be protected (leading them to demand that we revert back to a time when men protected rather than exploited women). The morality motivation is therefore not bound by political ideology both in terms of who is engaging in action for the disadvantaged group and the cause they are participating for (so long as there is still a power distinction between the groups which denotes the involvement of an advantaged and disadvantaged group).

Identification

Importantly, even though moral beliefs are theorized to be independent of personal or group identities, they can prompt people to develop a superordinate politicized identity which is associated with action for the disadvantaged group. According to the extended SIMCA model (Van Zomeren et al., 2018), moral beliefs form a psychological basis from which individuals may develop a politicized identity, if they perceive a normative fit between the content of their moral beliefs and the politicized group identity. Indeed, Van Zomeren and colleagues (2011) found that an advantaged group member’s moral beliefs about social inequality motivated their identification with the disadvantaged group (a form of politicized identification) and, subsequently, participation in action for this group. We, therefore, might expect that moral beliefs that align with taking action for the disadvantaged group might over time facilitate identification with a politicized group which fights for the rights of the disadvantaged group, making this an additional antecedent of the morality motivation.

Emotions

Perceived violations of moral principles are experienced as highly emotional (Skitka, 2010), more so than violations of non-moralized social norms. Moral transgressions can evoke especially strong and specific emotions, such as outrage, contempt, and disgust (e.g., Graham & Haidt, 2012; Tetlock, 2003). Moral outrage is a form of anger provoked by the perception that a moral standard has been violated (Batson et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2009b) and has been described as one of the key emotional responses predicting the engagement in prosocial behavior (see, for instance, Van de Vyver & Abrams, 2017). Leach and colleagues (2002) argue that advantaged group members will experience moral outrage when the focus is on the disadvantaged group, and the existing intergroup inequality is perceived to be unjust and unstable. Those who feel morally outraged are more likely to engage in a range of actions for the disadvantaged group (Montada & Schneider, 1989; Thomas et al., 2012; Thomas & McGarty, 2009). Importantly, moral outrage can be shared between both the advantaged and disadvantaged group, and thus provide them with shared norms which prescribe actions to redress the injustice (Saab et al., 2015; Thomas et al., 2009b).

Summary

Advantaged group members can be motivated to take action for the disadvantaged group because doing so aligns with their moral beliefs. We predict that if the disadvantaged group’s situation is perceived as violating the advantaged group members’ moral beliefs such as universalism, fairness, or harm avoidance, it will evoke strong emotional reactions, including moral outrage, that motivate them to act. Moreover, these violations of one’s moral beliefs can also lead to identification with a politicized group which includes the disadvantaged group, if the normative content of this politicized identity fits with one’s moral beliefs.

Behavioral Outcomes

We now turn our attention to the behavioral outcomes associated with each motivation using theories grounded in the social identity approach (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). We will focus on the literature on prosocial behavior, particularly the work on intergroup helping which makes the distinction between autonomy- and dependency-oriented help (Nadler & Halabi, 2006), and on the distinctions between normative and nonnormative action as well as between private and public behavior (Wright et al., 1990). Finally, we turn to the limited but emerging literature on advantaged group allyship (e.g., Droogendyk et al., 2016). Throughout, we are guided by the goals advantaged group members hope to achieve by participating in action for the disadvantaged group—improving the status of the disadvantaged group, supporting or maintaining the position of the ingroup, meeting personal needs, and rectifying a violation of a moral standard.

Intergroup Helping

In their analysis of the help provided by advantaged group members to the disadvantaged group—what they call intergroup helping—Nadler and Halabi (2006) focus on a critical distinction between dependency- and autonomy-oriented help. We propose that this distinction offers a useful model of the kind of actions that might be taken for the disadvantaged group by those with ingroup-focused motivations compared with outgroup-focused and some cases of morality motivations. Dependency-oriented help involves the helper making the recipient dependent upon them by providing the full solution to a problem, as opposed to autonomy-oriented help, which assists the recipient in solving the problem themselves.

Nadler and colleagues (2009) propose that in intergroup exchanges, dependency-oriented help is used to reinforce the dominant position of the higher status group by making lower status groups dependent on the help they provide. Thus, advantaged group members guided primarily by the ingroup-focused motivation should prefer this kind of help. Conversely, advantaged group members primarily guided by outgroup-focused motivations should prefer actions that involve autonomy-oriented help. For example, those focused on the outgroup might be more likely to circulate a petition which demands that refugees receive support from the government that allows them to acquire the skills (e.g., language training) they need to be successful or that provides financial support in a way that allows them to make decisions about the best ways to provide for themselves. However, those motivated more by ingroup interests might be more likely to support a petition which demands that refugees be provided with things that the advantaged group thinks they need through payments in kind—such as food coupons and clothes (Becker et al., 2018).

In the case of actions spurred by morality concerns, we propose that whether autonomy-oriented or dependency-oriented help will be preferred is dependent upon the specific content of the moral principle that is guiding the action. If action is the result of moral outrage about the unjust inequality faced by the disadvantaged group, then autonomy-oriented help should be the most preferred action. This prediction is consistent with recent research showing that both advantaged (e.g., Germans) and disadvantaged group members (e.g., refugees) believe that autonomy-oriented help has greater potential to produce genuine improvements to the status of the disadvantaged group (e.g., refugees in Germany) than does dependency-oriented help (Becker et al., 2018). However, if the advantaged group member is responding to moral outrage that results from observing the harmful mistreatment of disadvantaged group members by other powerful agents, the form of helping may be less important than ensuring that the offenders are punished. For example, when White Canadians are angered and disgusted by the abuses perpetrated against Indigenous children at residential schools, they may focus solely on punishing those perpetrators. Thus, moral outrage at the harm done may lead them to act without adequate consultation with members of the disadvantage group or meaningful reflection on how their efforts to punish perpetrators may cause further harm to Indigenous peoples. Therefore, while morality motivated action may be vigorous and genuine in its effort to right the moral wrong, whether the action will be autonomy-oriented or dependency-oriented will depend on what the advantaged group member sees as the necessary solution to the moral violation.

Similarly, we would expect that either dependency- or autonomy-oriented help could be taken by those motivated by personal self-interest, again depending on the specific content of that interest. For those seeking personal aggrandizement or to enhance their reputation, dependency-oriented help that leads to recognition of them as an individual (e.g., making a public donation to a cause, or being the spokesperson who holds the bullhorn at the rally) may be most preferred, as it clearly shows the superiority of the helper. However, those motivated by a desire to be accepted or liked by one’s peers or to gain personal financial benefits might be less concerned about the impact of the action on the disadvantaged group, because these motivations are not concerned with maintaining or challenging the relative status of the two groups.

Normative and Nonnormative Action

Normative action refers to behaviors that conform to the norms of the dominant social system (e.g., in most contemporary Western democracies, this would include peaceful protests, signing a petition, writing a letter to a politician). Nonnormative action refers to behaviors that violate these rules (e.g., boycotting, picketing, or participating in a disruptive sit-in; Wright et al., 1990). We expect that advantaged group members who are focused on the outgroup and/or are morality motivated will be equally likely to engage in normative and nonnormative action (the decision of which will depend on what action best seeks to genuinely improve the status of the outgroup or uphold their moral beliefs, respectively). We propose that this is because advantaged group members who are driven primarily by these motivations are less concerned about the potential costs of their actions for their ingroup and/or themselves and more focused on the potential effectiveness of the action.

This argument is supported by research on moral courage (where bystanders intervene against the violations of a perpetrator despite the potential for negative consequences for oneself; for example, Baumert et al., 2013; Greitemeyer et al., 2007). Baumert and colleagues (2013) describe moral courage as distinguishable from helping behavior, because it is associated with the expectation that intervening will result in more negative than positive social consequences for the actor. They provide as an example of moral courage where a young woman who stepped in to prevent thieves from stealing an older woman’s purse despite the risks to herself (she was later beaten up by the thieves; Moral Courage, 2009). Previous research has found that when participants were asked to write about a situation in which they had showed either moral courage or helping behavior, the participants who wrote about helping behavior expected more positive social consequences, but the participants who wrote about moral courage expected more negative social consequences for intervening (Greitemeyer et al., 2006). Like moral courage, engaging in nonnormative action requires participants to accept the potentially negative social, physical, and/or resource consequences of their actions for themselves and/or their ingroup. Thus, this type of action should usually emerge as a result of a genuine desire to improve the status of the disadvantaged group or a desire to adhere to one’s moral beliefs.