Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a serious, life-altering condition. Patients who are diagnosed are often of childbearing potential. Given the well-documented risks associated with this condition during pregnancy, as well as risks to the fetus from medications used to treat this disorder, patients should be strongly advised against pregnancy. Despite this, patients still become pregnant, leading to the question of whether care providers are counseling patients and their partners about the risks of pregnancy, methods of contraception, and issues of intimacy on a regular basis. We have conducted a survey of pulmonary hypertension specialist physicians and allied healthcare professionals on their practice patterns related to counseling on intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy prevention. Most respondents indicated they are counseling on these issues to varying degrees, but our survey pointed to several areas where improvements can be made. The most significant barrier to counseling for all respondents was lack of time. Survey respondents reported that a large percentage of the pregnancies seen in their practices were either intentional or due to contraceptive non-compliance. We review specific practical approaches to initiate reproductive health counseling as well as ways to integrate this important aspect of PAH care into regular practice routines and documentation. Protocols regarding pregnancy avoidance and PAH should be developed and become standard procedure.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, intimacy

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a complex and difficult disorder to manage. PAH is defined by a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥ 25 mmHg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) ≤ 15 mmHg, and a pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) > 3 Wood units.1 This increased PVR leads to right ventricular dysfunction and failure, ultimately resulting in death if left untreated.2,3

Any increased cardiovascular demand, as occurs during pregnancy, can present challenges to the ongoing management of patients with PAH. During pregnancy, hemodynamic changes worsen PAH because of mechanical compression by the expanding uterus, increases in sex hormones, and dramatic increases in circulatory volume.4 The increase in blood volume during pregnancy, as much as 40–100% from baseline, is accompanied by a decrease in both systemic vascular and PVR, with an increase in cardiac output.5 In PAH, the pulmonary vasculature cannot accommodate this increase in PVR, resulting in decreased cardiac output and right heart failure.5,6 Labor and delivery and the postpartum period also present significant risks, primarily due to dramatic volume shifts and intravascular pressure swings.4 Pregnancy-related mortality in most patients with PAH occurs in the first month after delivery due to heart failure and sudden death.4,7,8 While maternal mortality rates in pregnant patients with PAH may have improved slightly in recent years with rates noted in the literature in the range of 12–50%, the rates remain unacceptably high.7,9,12

As a result of the high mortality rate, current guidelines and recommendations contraindicate pregnancy in patients with PAH, and state that patients should be counseled on birth control methods and pregnancy prevention.2,4,13,14 Despite these recommendations, more women with PAH of childbearing age may be considering pregnancy. Improved survival and functional status due to advances in medical care and treatment for PAH may lead patients to consider having children. Additionally, anecdotal reports of isolated successful pregnancies in patients with PAH in support groups and on social media may influence a patient’s decision to consider pregnancy. Even when patients with PAH are properly counseled, patients may become pregnant and not wish to terminate. In these cases, patients should receive advanced care and be referred to a pulmonary hypertension (PH) center to ensure the safety of mother and baby.2,4,9–11,15

Intimacy

Diagnosis of PAH has a considerable impact on intimacy. A qualitative study by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association (PHA) of American and European patients and caregivers found that approximately 75% of patients had difficulty being fully intimate with their partners and 20% reported this as their number one concern.16,17 Sixty-five percent stated they had difficulty fulfilling the role of spouse/partner within their personal relations. When asked about the cause of the loss of libido, 29% cited low self-esteem/negative body image, 24% one or more serious diseases or conditions in addition to PAH, 20% loss of interest since their PAH diagnosis, 14% not physically able, 5% getting more ill, and 41% “other.” No patients stated their lack of interest in sex was related to fear of pregnancy.16 Correspondingly, 72% of caregivers who are partners of patients with PAH reported a decrease in sexual relationships.17 Caregivers feel less close to their spouse (23%) and feel that their spouse sees them more as a caregiver than as a lover (18%).17 Intimacy is impacted by breathlessness and fatigue during sexual activity. Additionally, negative body image caused by medical devices (oxygen, infusion pumps, and catheters) and altered physical appearance (e.g. edema, flushing, and ascites) may also affect intimacy.

Intimacy issues of patients with chronic diseases often are not addressed. Most patients do not take the initiative to ask healthcare professionals (HCPs) about sexual problems. When discussions regarding contraception and pregnancy prevention do occur, very little time is devoted to intimacy.18

Contraception

Contraception is essential in patients with PAH to prevent pregnancy and potential teratogenicity related to specific PAH medications: riociguat; bosentan; macitentan; and ambrisentan.19–22 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classified contraceptives into three tiers based on effectiveness.23 Tier I contraceptives with a failure rate of <1% are recommended for all patients in World Health Organization (WHO) pregnancy risk group IV (pregnancy contraindicated). These include male and female sterilization, implants, and intrauterine devices (IUDs). Tier II contraceptives with a 6–12% failure rate include injectables, pills, patch, vaginal ring, and diaphragm, and are not recommended as a single form of contraception.23

All females that take specifically identified PAH medications are required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to enroll in a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). The goals of REMS for medications used to treat PAH are to inform prescribers, patients, and pharmacists about the risks of using the medication, to minimize the risks of patients exposed to the medications, and to educate prescribers, patients, and pharmacies on the safe-use conditions of the medication.24 Only an IUD, tubal sterilization, or progesterone implant is recommended as a single form of contraception. Note that monthly pregnancy tests are still required. Vasectomy requires a second form of contraception. Hormonal methods require a barrier method in addition and if only barrier methods are chosen, then two barrier methods must be used concurrently.19–22

Previous studies in patients with diseases where pregnancy is contraindicated have shown a lack of proper counseling in pregnancy prevention.25,26 For example, studies of patients with congenital heart disease have shown that as many as 43% of women with a moderate or high risk of maternal complications do not remember being counseled on the risks of pregnancy.26 To our knowledge, studies addressing whether patients with PAH are being properly counseled on pregnancy prevention do not exist. The goal of this study was to survey current counseling practices among PAH HCPs for patients with PAH regarding intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy prevention. Our results can be used to inform PAH professionals about improvements that can be made when discussing these issues.

Methods

Survey design

We designed a survey to assess current practices of PH clinicians regarding counseling of intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy prevention in PAH (WHO Group I PAH) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The survey was conducted anonymously using the online survey website surveymonkey.com and had Houston Methodist Research Institute institutional review board (IRB) approval (Study ID Pro00018111). To target PH practitioners, the survey was sent via email listserv to two professional networks associated with the PHA: the Pulmonary Hypertension Professional Network (PHPN), which includes allied healthcare professionals (AHCP) caring for PH patients; and pulmonary hypertension clinicians and researchers (PHCR), which includes physicians and researchers in PH. The survey was conducted from 8 November to 21 November 2017 for PHPN members and 8 December to 15 December for PHCR members. While the survey was sent to the PHPN for two weeks, the first week the survey was not accessible to members of the PHPN due to an administrative complication, therefore, both PHPN and PHCR members had a one-week time period to answer the survey. Two reminders were sent to the PHPN members and one to PHCR members.

The survey consisted of demographic questions to assess the type of practitioner answering the survey and the type of center at which they practice (Supplementary Fig. S1). To query how often the topics of intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy prevention were being addressed in the survey respondent’s practice, we asked a series of questions regarding frequency of discussion, specific topics discussed, and outcomes of counseling in terms of number of pregnancies and status of the mother and baby after birth (Supplementary Fig. S1). For certain questions, the respondents could select more than one response; therefore, presented data may be based out of the total number of AHCPs or physicians and the totals within each question may not equal 100%.

Statistical analysis

Percentage was calculated based on the number of respondents in each group (AHCPs vs. physicians) if not otherwise specified. The Chi-square test of independence was used to determine if there was a significant association between response from AHCPs and that from physicians. No substitution or data imputations for missing data were made.

Results

Survey response

Out of the 403 members of PHPN and 338 members of PHCR, we received 116 total responses (a total response rate of 15.6%). We included 105 respondents’ answers in our final data analysis. We excluded from our survey all data from any respondent who: (1) completed only the demographic questions (questions 1 and 2); (2) completed < 9 of the 15 questions; and (3) did not identify as one of the specified professional roles in question 1. In total, 11 respondents were excluded. We included data from all other respondents, including those who did not answer every question if they answered nine or more questions in total.

Demographics

In total, 105 PH HCPs responses were included in our analysis: 43 physicians and 62 who identified as one of the categories we classify as AHCP (Supplementary Fig. S2). Just over half of the respondents in the AHCP category were registered nurses and another 28% were nurse practitioners (Supplementary Fig. S2). The majority of respondents were from an academic medical center (79% AHCP, 84% physicians) and 36% were from PHCC accredited programs (Comprehensive Care Centers or Regional Clinical Programs) (Table 1). Both AHCPs and physicians responded that the physician discusses intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy with the patient most often (94% and 98%, respectively), but they also identified nurse practitioners and registered nurses as discussing these issues (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and basic practice patterns.

| AHCP (n = 62) |

Physician (n = 43) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| My practice is… Select all that apply. | ||||

| Community/private practice | 5 | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Academic medical center | 49 | 79 | 36 | 84 |

| Accredited Centers of Comprehensive Care (CCC) | 21 | 34 | 15 | 35 |

| Accredited Regional Clinical Programs (RCP) | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Inpatient only | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| In your practice, who speaks to the patient about intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy avoidance? Select all that apply. | ||||

| Physician | 58 | 94 | 42 | 98 |

| PA (physician assistant) | 10 | 16 | 3 | 7 |

| NP (nurse practitioner) | 33 | 53 | 17 | 40 |

| CNS (clinical nurse specialist) | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| RN (registered nurse) | 44 | 71 | 27 | 63 |

| LVN/LPN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MA (medical assistant) | 4 | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Study coordinator | 10 | 16 | 7 | 16 |

| Pharmacist | 8 | 13 | 2 | 5 |

| Respiratory therapist | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Social worker | 2 | 3 | 5 | 12 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| When do you discuss contraceptive methods and pregnancy avoidance/contraindication with women of childbearing potential (CBP)?* | ||||

| A few times per year | 20 | 32 | 20 | 47 |

| Annually | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Every clinic visit | 21 | 34 | 6 | 14 |

| Only on the first visit | 9 | 15 | 4 | 9 |

| Random intervals when I remember it, or when the patient brings it up | 12 | 19 | 11 | 26 |

Chi-square test of independence; P = 0.0378.

General practice patterns

The two groups differed significantly in how frequently they discuss contraceptive methods and pregnancy avoidance/contraindication (Chi-square test of independence; P = 0.0378). AHCPs responded that they discussed pregnancy avoidance “at every visit” (34%) followed by “a few times a year” (32%) and then “random intervals” (19%). Physicians responded that they discussed the topic “a few times a year” (47%), followed by “random intervals when I remember it or when the patient brings it up” (26%) (Table 1).

In most other areas, AHCPs and physicians responded similarly. AHCPs and physicians most often discussed intimacy at “random intervals when I remember or when the patient brings it up” (44% vs. 51%, respectively) (Table 2). HCPs responded that they do not routinely ask patients the date of their last menstrual period (LMP) (45% AHCP vs. 65% physician) (Table 2). Respondents also indicated they consult with other providers regarding contraception and pregnancy avoidance, most often with an OB/GYN (53% AHCPs vs. 72% physicians) (Table 2). When contraception and pregnancy avoidance was discussed, the discussion occurred in the clinic (92% AHCPs vs. 98% physicians) and not over the phone or in the hospital (Table 2).

Table 2.

General practice questions.

| AHCP (n = 62) |

Physician (n = 43) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Where do MOST of your counseling sessions/discussions about contraception and pregnancy avoidance occur? | ||||

| During a clinic visit | 57 | 92 | 42 | 98 |

| In the hospital | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Over the phone | 4 | 6 | 0 | |

| Do you ask female patients of CBP for the date of their last menstrual period at every routine visit? | ||||

| No | 28 | 45 | 28 | 65 |

| Yes, for all patients | 18 | 29 | 8 | 19 |

| Yes, only for PAH patients who are covered under REMS) receiving ERA or sGC agonists) | 15 | 24 | 7 | 16 |

| When do you discuss intimacy with women of CBP? | ||||

| A few times per year | 17 | 27 | 12 | 28 |

| Every clinic visit | 8 | 13 | 4 | 9 |

| I do not discuss this with my patients | 8 | 13 | 4 | 9 |

| Only on the first visit | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Random intervals when I remember it, or when the patient brings it up | 27 | 44 | 22 | 51 |

| Do you consult with any other provider the patient may see regarding intimacy, contraception, or pregnancy avoidance counseling? Select all that apply. | ||||

| OB/GYN | 33 | 53 | 31 | 72 |

| PCP (primary care physician) | 17 | 27 | 18 | 42 |

| No, I do not consult with other providers regarding this issue. We address this with the patient in our department | 22 | 35 | 12 | 28 |

| Other | 8 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you prefer to involve the patient’s sexual partner in discussions of intimacy, contraception, or pregnancy avoidance? | ||||

| Don’t have a strong preference either way for including the partner in this discussion | 27 | 44 | 21 | 49 |

| No, I find it easier to speak to the female patient alone | 10 | 16 | 5 | 12 |

| Yes, whenever possible | 25 | 40 | 17 | 40 |

| If you ask patients what method they plan to use for contraception, when do you ask?* | ||||

| A few times a year | 16 | 28 | 13 | 30 |

| Annually | 3 | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Every clinic visit | 20 | 35 | 7 | 16 |

| I do not discuss this with my patients | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Only on the first visit | 3 | 5 | 5 | 12 |

| Random intervals when I remember it, or when the patient brings it up | 15 | 26 | 11 | 26 |

AHCP, n = 57; physician, n = 43.

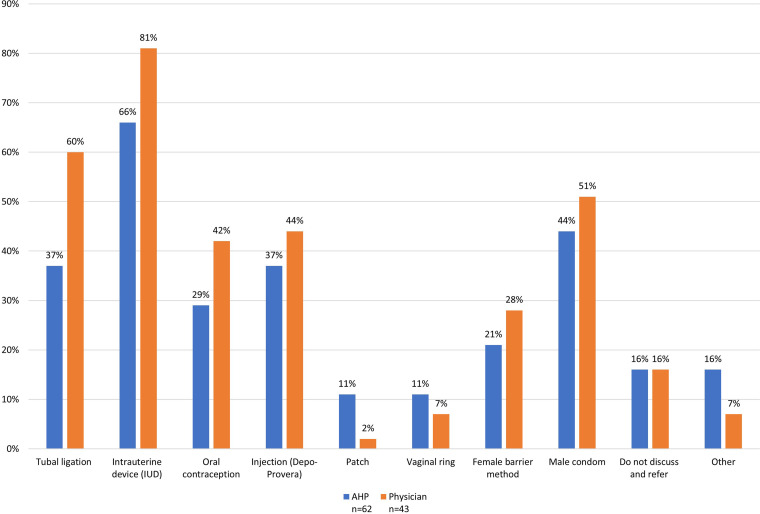

Contraception

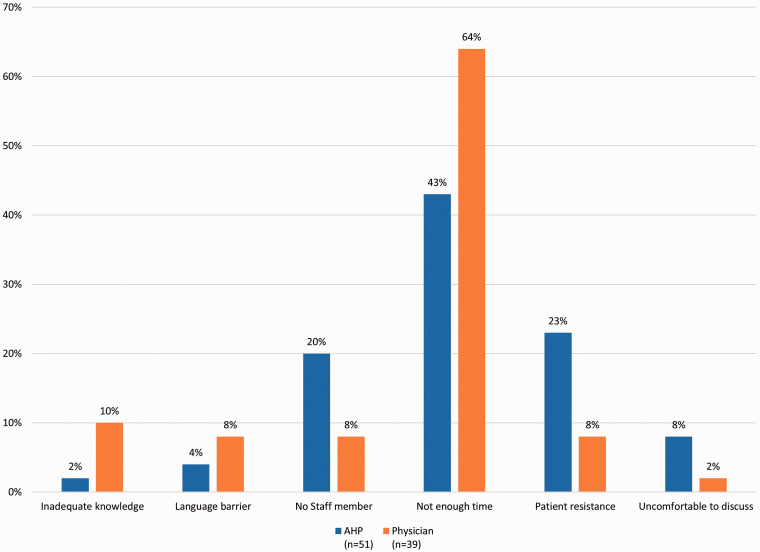

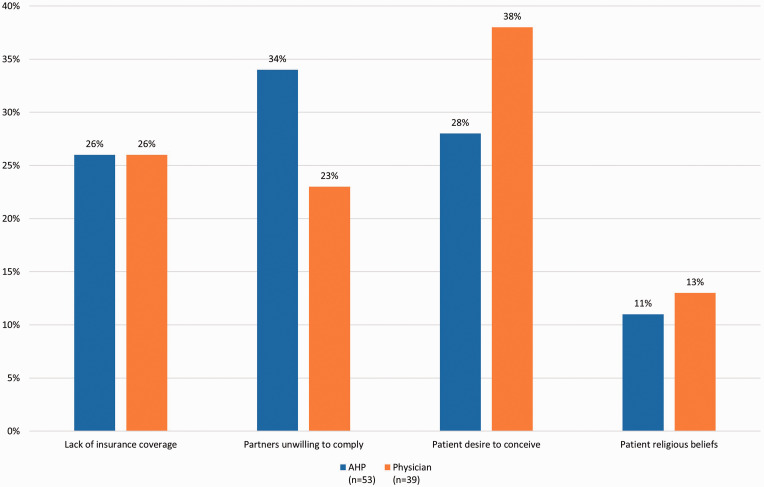

Both AHCPs and physicians responded similarly when asked when/how often they ask patients about their method of birth control (Table 2). IUDs were the most frequently recommended form of contraception (66% AHCPs vs. 81% physicians), followed by tubal ligation (37% AHCPs vs. 60% physicians) (Fig. 1). When asked about the most significant barrier to discussing contraception and pregnancy avoidance, the overwhelming response from both AHCPs and physicians was “not enough time” (43% AHCPs vs. 64% physicians) (Fig. 2). When asked about the most significant barrier to patient compliance with contraception, AHCPs and physicians responded similarly, with three factors split as the most significant: “patient desire to conceive” (28% AHCPs vs. 38% physicians); “partners unwilling to comply” (34% AHCPs vs. 23% physicians); “lack of insurance coverage” (26% for both); and “patient religious beliefs” (11% AHCPs vs. 13% physicians) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

What do you recommend for contraception? Select all that apply.

Fig. 2.

Please rank the following in order of importance from 1 to 6, with 1 being the most significant barrier and 6 the least significant for you when discussing contraception and pregnancy avoidance. The most significant barrier reported is shown.

Fig. 3.

Please rank the following in order of importance from 1 to 4, with 1 being the most significant barrier and 4 the least significant for patient compliance with contraception use. The most significant barrier reported is shown.

Pregnancy

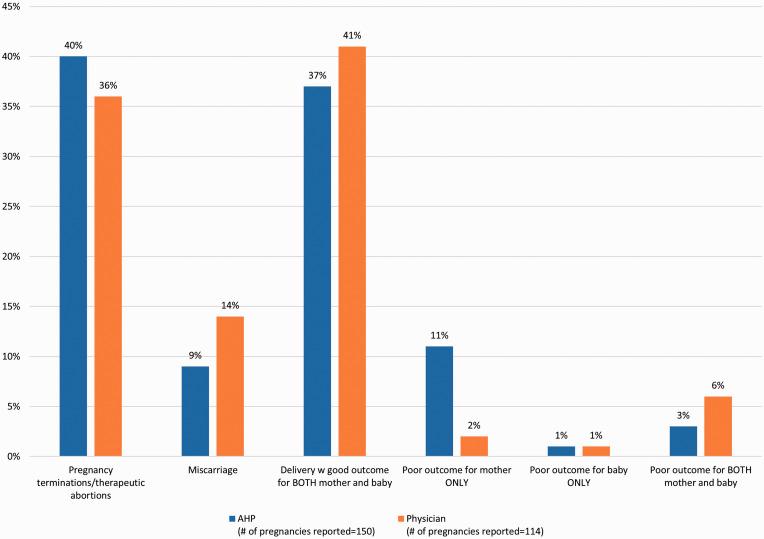

When asked about pregnancies in the past five years, AHCPs vs. physicians reported 40% vs. 54% were intentional, 46% vs. 32% were due to contraceptive non-compliance, respectively, and only 14% were due to contraceptive failure reported by both groups (Supplementary Fig. S3). The reported outcomes of pregnancies in patients with PAH were: “delivery with a good outcome for both mother and baby” (37% in the AHCP group vs. 41% in the physician group) (Fig. 4). “Pregnancy terminations/therapeutic abortions” were reported in 40% (AHCPs) vs. 36% (physicians) of pregnancies (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

In the past 5 years, what outcomes did your pregnant patients with PAH experience? Enter a number, including 0, for all categories.

Discussion

Our survey has indicated varying practice patterns by PH HCPs related to discussions about intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy with patients with PAH. While the study results were not designed to identify AHCP vs. physician practice patterns, there were some differences. For example, AHCPs differed from physicians in how frequently they discussed contraceptive methods and pregnancy avoidance/contraindication. AHCPs responded that they discussed pregnancy avoidance “at every visit,” while physicians responded that they discussed the topic “a few times a year,” followed by “random intervals when I remember it or when the patient brings it up.” In other areas, AHCPs and physicians responded similarly, such as the overwhelming response from both AHCPs and physicians that the most significant barrier to discussing contraception and pregnancy avoidance was “not enough time.” Identifying other HCPs, like OB/GYNs, that may address intimacy and contraception may help alleviate this time constraint.

The relatively high percentages of pregnancies that were intentional or due to contraceptive non-compliance may indicate that patients either have a poor understanding of the risks or have not come to terms with the implications of PAH on reproductive health. Self-management of chronic illness requires the patient/caregiver to manage issues in four areas: recognizing symptoms and taking the appropriate response; adhering to medication regimens; developing strategies to cope with the psychological consequences of chronic illness; and negotiating the healthcare system.27 These areas can be applied to counseling patients with PAH to avoid pregnancy. Schulman-Green identifies several tasks for coping with a chronic illness. Processing emotions entails exploring and expressing emotions and grieving the loss of the “normal.” When counseling a woman of CBP to avoid pregnancy, it may be best to start with the recognition of the “unfairness” of not being able to have a child. Encouraging the exploration of these feelings and starting the grieving process may be necessary to come to terms with their changed life and self. The illness must be integrated into their daily life by modifying lifestyle and adapting to what patients describe as their “new normal.” Finding meaning in illness is defined by a re-evaluation of life with personal growth.27 Although these tasks are somewhat temporal, there is considerable overlap and interaction. Individuals will vary in how or when processes are prioritized and in what effective coping strategies they adopt. These also change over time as their disease progresses or outside factors interfere.

In our survey, AHCPs and physicians responded similarly about discussions of intimacy, which most often occur at random intervals in the clinic, not over the phone or in the hospital. Patients with PAH and their partners face obstacles to both emotional and physical intimacy.16,17 Patients and their partners may no longer feel like equals in the relationship because partners may feel they are caregivers and no longer lovers. The forced dependency of the patient may promote a child-like position in the relationship. Stress on both parties can cause irritability that impedes emotional closeness. Lastly, disease symptoms, depleted energy, negative body image, and therapy paraphernalia may all interfere with physical intimacy.

Discussions of intimacy with female patients is not a regular part of most HCPs’ practice. Intimacy is either not discussed, only at random intervals, or when brought up by patients as reported by 57% of AHCPs and 60% of physicians. HCPs may be reluctant or uncomfortable beginning these discussions. Table 3 presents several possible approaches for how to begin the discussion of intimacy, adapted from Jaarsma et al.28 A good approach is to assume the patient is interested in sexual matters, but also to be mindful of the differing comfort levels of the patient regarding these conversations.28 Our survey showed that AHCPs and physicians preferred to involve the patient’s sexual partner only 40% of the time in discussions of intimacy, contraception, or pregnancy avoidance (Table 2). Including the partner in these sessions allows the HCP to evaluate the couple’s communication and their respective roles as patient–caregiver–partner. Caregiver/partners may experience loss of their “normal” partner and need to process their feelings and grief. When counseling adolescents, involvement of the parent/guardian should first be cleared with the patient.

Table 3.

Possible approaches to intimacy assessment (adapted from Jaarsma et al.28).

| Approach | Description | Dialogue example |

|---|---|---|

| Unfairness of loss | Acknowledge the emotion and recognize unfairness | “I know how unfair not being able to start a family must feel. What are your thoughts and feelings about this?” |

| Gradual | Starting with broad health assessment and narrow in about sex as part of the normal assessment | “I've asked about your general health and now I’d like to ask some questions about more intimate functions that are equally important.” |

| Matter-of-fact | Use research or the experience of other patients to broach the topic | “Many PAH patients express concerns regarding sexual matters. What concerns do you and your partner have?” |

| Context | Discuss sex when talking about activity or exercise or the effect of disease or treatment on ADLs | “As a general guide, when you can go up one flight of stairs without symptoms, you are able to engage in sexual activity. What kinds of activities have you tried or wonder about?” |

| Sensitivity | Specifically asking permission to discuss sex with patients/partners whom you feel may be resistant. | “Some people are uncomfortable talking about sex, but it is important for many of my patients. Can I ask you a few questions?” |

| Standard of care | Sexual function is a normal part of life and assessing and treating sexual dysfunction is standard of care for all patients | “In our clinic we feel sex is an important area to discuss with all our patients. I would now like to ask you a few questions about this.” |

ADL, activity of daily life.

In many cases, limited general information about sexual activity may be all that is required. Simply telling the patient/partner that it is safe to engage in sexual activity based on the patient’s functional status may be enough. In some cases, patients/partners need specific suggestions on sexual positions to avoid or try, or how to manage lines and pumps, and how to conserve energy or plan for sexual activity. Based on the assessment, if therapy is warranted, a referral to a specialist (OB/GYN, urologist) or sexual therapist can help.

In our survey, discussions about contraception were similar between AHCPs and physicians in when/how often they ask patients about their method of birth control, whether they consult with other providers, and that IUDs were the most frequently recommended form of contraception, followed by tubal ligation. There are no specific guidelines describing which contraceptive methods are best for patients with PAH and the role of estrogen is still unresolved.2,12,29,30 Therefore, we recommend adhering to PAH medication REMS contraceptive guidelines. Current contraception, issues related to contraception, and LMP should be addressed at every clinic visit and documented. This can be incorporated into the medication reconciliation process. Documentation, such as using an electronic medical record (EMR) “smart phrase” or “template” may help improve the frequency in which these topics are discussed. The nurse or intake staff member should be alert to cues that the patient/partner may wish to discuss contraception, intimacy, and reproductive issues and forward their concerns to the PH provider.

When asked about pregnancies in the past five years, AHCPs and physicians responded similarly: of reported pregnancies, approximately half were intentional, half to one-third were due to contraceptive non-compliance, and about one-sixth were due to contraceptive failure. Investigating the attitudes and knowledge of patients and their partners could elucidate the reasons for the high rates of intentional pregnancy and contraceptive non-compliance and provide guidance for interventions to reduce these rates. If pregnancy occurs, termination should be offered, particularly to high-risk patients.4 However, some women will elect to continue the pregnancy against medical advice, which was clearly evident in our survey results. Case reports and opinion articles describe the required care for a pregnant patient with PAH.4,7,9,11,31 The common theme of these reports is the complex, resource-intensive nature of this care and the importance of good communication between team members. Advanced practice nurses and PH coordinators are in key positions to facilitate communication and coordinate care of these complex patients.

Lack of time to discuss reproductive issues in clinic was cited as the most significant barrier to having these discussions by 43–64% of survey respondents (Fig. 2). PH HCPs therefore should develop protocols, patient education materials, job aides, and documentation aides to assist in the efficient delivery of reproductive counseling to patients. Patient education materials in English and Spanish are available from pharmaceutical companies for medications that carry a REMS. Educational information is also available from the PHA or may be developed by medical institutions and PH programs. Counseling roles should be identified by the PH practice, personnel assigned to various responsibilities, and documentation facilitated through mechanisms in the EMR. Pregnancy prevention, contraception, and intimacy counseling should be a proactive, regular, and routine part of patients’ clinic experience.

The study limitations include an overall response rate of 15.6% out of the total number of PHPN and PHCR members. This response rate is in line with what has been seen in previous online surveys. For example, in this online survey of self-reported physician practices in PAH conducted by Polanco-Briceno et al, the response rate was 7% (2594 invited/184 entered).32 This survey was conducted anonymously, and as such, some of the data may have been collected from individual HCPs at the same institutions or in the same departments. In addition, these are qualitative real-world data for which there are no benchmarks. The survey relied on self-reported data, therefore, provider reporting may not reflect actual practice. The number of pregnancies reported may not reflect the actual number of pregnancies that occurred in these practices. We did not survey patients with PAH, only physicians and AHCPs. Patients’ perceptions of counseling on intimacy, pregnancy prevention, and contraception may be very different from those of providers. Surveying patients’ knowledge and attitudes regarding reproductive issues should be considered for future research.

Conclusion

Our goal is to increase awareness of the need for regular counseling on intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy avoidance. Our survey results identified practice variations in counseling patients with PAH on these topics. As part of a holistic approach to the wellbeing of patients with PAH, we are not only responsible for the physical care of our patients but also for their emotional wellbeing. Pregnancy remains a very dangerous condition for patients with PAH and it is our responsibility to counsel patients and their partners on reproductive issues. HCPs may have varying knowledge, communication skills, and comfort levels to address sensitive reproductive health issues; however, our patients rely on us to begin the discussion. Contraception and pregnancy prevention should be discussed on a routine basis. Protocols regarding pregnancy avoidance and PAH should be developed, similar to “identifying patients at risk for falls” or “assessing for pain,” which are all now considered standard procedure for most practices. Integrating intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy avoidance counseling into routine PAH care will ensure patients are educated and can make well-informed medical decisions with their care providers.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary Figures for Intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy prevention in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: are we counseling our patients? by Wendy Hill, Royanne Holy and Glenna Traiger in Pulmonary Circulation

Acknowledgments

Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc. provided funding for this manuscript produced by Katie Estes, PhD, of Simcoe Consultants, Inc., and did not contribute to the content nor provide any review or editorial support. The manuscript was written independently by the authors with writing support provided by Katie Estes, PhD and managed by Donna Simcoe, MS, MS, MBA, CMPP of Simcoe Consultants, Inc. All statements and opinions expressed in the manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect those of Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc. or its representatives. The authors thank Saling Huang and Carol Zhao of Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc. for help with statistical analysis.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare the following conflicts of interest: Wendy Hill: speaker bureau member and advisory board member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Bayer Corporation, Gilead Sciences Inc., Lung Biotechnology LLC, and United Therapeutics Inc.; Royanne Holy: advisory board member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Inc.; and Glenna Traiger: speaker bureau member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Bayer Healthcare, Gilead Sciences, Inc., and United Therapeutics Corporation.

Funding

Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc provided funding for this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hoeper MM, Bogaard HJ, Condliffe R, et al. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: D42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Respir J 2015; 46(4): 903–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62(25 Suppl): D34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemnes AR, Kiely DG, Cockrill BA, et al. Statement on pregnancy in pulmonary hypertension from the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute. Pulm Circ 2015; 5(3): 435–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safdar Z. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in pregnant women. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2013; 7(1): 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pieper PG, Hoendermis ES. Pregnancy in women with pulmonary hypertension. Neth Heart J 2011; 19(12): 504–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bédard E, Dimopoulos K, Gatzoulis MA. Has there been any progress made on pregnancy outcomes among women with pulmonary arterial hypertension? Eur Heart J 2009; 30(3): 256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss BM, Zemp L, Seifert B, et al. Outcome of pulmonary vascular disease in pregnancy: a systematic overview from 1978 through 1996. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 31(7): 1650–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaïs X, Olsson KM, Barbera JA, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Eur Respir J 2012; 40(4): 881–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duarte AG, Thomas S, Safdar Z, et al. Management of pulmonary arterial hypertension during pregnancy: a retrospective, multicenter experience. Chest 2013; 143(5): 1330–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng ML, Landau R, Viktorsdottir O, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in pregnancy: a report of 49 cases at four tertiary North American sites. Obstet Gynecol 2017; 129(3): 511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scientific Leadership Council, Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Consensus Statement: Birth control and hormonal therapy in PAH. Silver Spring, MD: PHA, 2002. Available at: https://phassociation.org/medicalprofessionals/consensusstatements/birth-control/ (accessed 5 February 2018).

- 13.Badesch DB, Champion HC, Sanchez MA, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54(1 Suppl): S55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc.; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53(17): 1573–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss BM, Hess OM. Pulmonary vascular disease and pregnancy: current controversies, management strategies, and perspectives. Eur Heart J 2000; 21(2): 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Studer S, Chen H, Mullen M. The impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) on the lives of patients and caregivers: results from a US study, Silver Spring, MD: PHA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guillevin L, Armstrong I, Aldrighetti R, et al. Understanding the impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension on patients’ and carers’ lives. Eur Respir Rev 201; 22(130): 535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Harries C and Armstrong I. It matters to me: A guide to relationships and intimacy for people with pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK, 2014. Available at: www.phauk.com/living-with-pulmonary-hypertension/ph-and-you/relationships/.

- 19.Adempas® (riociguat) [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2013.

- 20.Tracleer® (bosentan) [package insert]. Mississauga, ON, Canada: Patheon, Inc.; 2003.

- 21.Letairis® (Ambrisentan) [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2015.

- 22.Opsumit® (Macitentan) [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Actelion Pharmaceuticals, US, Inc.; 2017.

- 23.Lindley KJ, Madden T, Cahill AG, et al. Contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 126(2): 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS). Silver Spring, MD: U.S. FDA. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm. (accessed 21 December 2017).

- 25.Kovacs AH, Harrison JL, Colman JM, et al. Pregnancy and contraception in congenital heart disease: what women are not told. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52(7): 577–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vigl M, Kaemmerer M, Seifert-Klauss V, et al. Contraception in women with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2010; 106(9): 1317–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulman-Green D, Jaser S, Martin F, et al. Processes of self-management in chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarsh 2012; 44(2): 136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaarsma T, Steinke EE, Gianotten WL. Sexual problems in cardiac patients: how to assess, when to refer. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2010; 25(2): 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin ED. Gender, sex hormones, and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Advances in Pulmonary Hypertension 2011; 10: 160–166. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santiago-Munoz P. Contraceptive options for the patient with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Advances in Pulmonary Hypertension 2011; 10(3): 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonnin M, Mercier FJ, Sitbon O, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension during pregnancy: mode of delivery and anesthetic management of 15 consecutive cases. Anesthesiology 2005; 102(6): 1133–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polanco-Briceno S, Glass D, Caze A. Self-reported physician practices in pulmonary arterial hypertension: Diagnosis, assessment, and referral. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2016; 2: 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary Figures for Intimacy, contraception, and pregnancy prevention in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: are we counseling our patients? by Wendy Hill, Royanne Holy and Glenna Traiger in Pulmonary Circulation