Dear Editor,

Dermatologists have experienced many challenges in management of autoimmune disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris during COVID‐19 pandemic era. 1

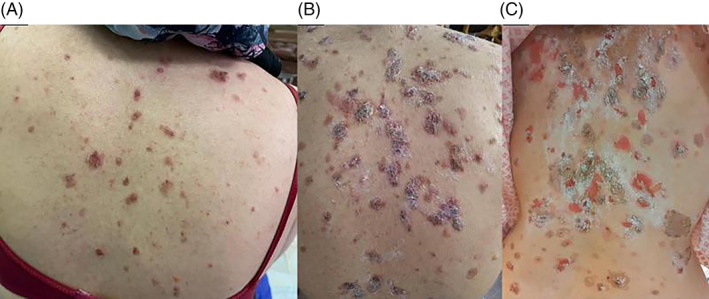

A 40‐year‐old female presented with bullae and erosions since 50 days ago (Figure 1A). In physical examination multiple bullae and erosions were seen on her scalp, trunk, upper, and lower limbs. Mucosal surfaces were intact. Skin biopsy for routine histopathology and immunofluorescence examinations were done and diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris was confirmed. We planned to start rituximab; therefore, all required examinations were checked for her. Evaluation for COVID‐19 showed negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test result and normal chest CT scan. Meanwhile, PPD test with 18 mm induration and a positive Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) were reported. According to infectious disease consultation, treatment with isoniazid 300 mg/day and B6 tablet were started for her. Soon she was hospitalized at dermatology ward COVID‐19 negative PCR branch and received 1 g rituximab without systemic steroid as adjuvant. After treatment cessation she was discharged, and recommended to stay isolated at home. Few days later, the patient came back showing a rapidly aggressive course with involvement of nasal mucosa and appearance of multiple bullae on her skin (Total activity score: 34, based on pemphigus disease area index PDAI]) (Figure 1B). A second COVID‐19 PCR test was done and meanwhile 0.5 mg/kg (40 mg) prednisolone daily was added to her treatment schedule. Her PCR test result was positive this time; consequently, we changed her treatment plan to IVIG 25 g/day for 5 days. Within the first 2 days of IVIg treatment, appearance of new lesions stopped (Figure 1C). Skin lesions started to dry and epithelialization appeared to start. Her general condition improved in a week. She was discharged, but few days later she noticed blurred vision. Ocular herpes was diagnosed for her and acyclovir 2 g daily for 10 days was administered immediately. Two weeks later, in a follow‐up visit her symptoms and skin lesions were ameliorated significantly (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Clinical presentation of pemphigus vulgaris. A, First presentation of pemphigus vulgaris. B, Skin lesions after first session of rituximab. C, Skin lesions during IVIg therapy

FIGURE 2.

Improvement of skin lesions in a follow‐up visit

Severe cases of pemphigus vulgaris are life threatening and may cause mortality rate of 10%. 2 Most studies suggest combining rituximab with low‐dose prednisolone in treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 However, in this patient we did not use any systemic steroid due to positive IGRA and the risk of COVID 19 infection; although we added oral prednisolone later in order to prevent further progression of the disease. Currently one of the main concerns in rituximab administration is the risk for COVID‐19 exposure upon hospitalization. Therefore maximum cautious must be considered to prevent such a risk. It is mandatory to treat patients in a unit specified to with COVID‐19 negative patients. Exacerbation of lesions secondary to administration of rituximab has been reported but COVID‐19 positivity is highly suspected in this patient. 7

We replaced her treatment protocol with IVIg, as in cases of pemphigus vulgaris associated with COVID‐19 infection IVIg is the treatment of choice. 4 , 5 , 6 Our patient was controlled with this treatment. Further investigations are needed to evaluate the most appropriate treatment schedule for pemphigus vulgaris in the COVID‐19 pandemic.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rademaker M, Baker C, Foley P, Sullivan J, Wang C. Advice regarding COVID‐19 and use of immunomodulators, in patients with severe dermatological diseases. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(2):158‐159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Porro AM, Seque CA, Ferreira MCC. Pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94(3):264‐278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shakshouk H, Daneshpazhooh M, Murrell DF, Lehman JS. Treatment considerations for patients with pemphigus during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):e235‐e236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kasperkiewicz M, Schmidt E, Fairley J, et al. Expert recommendations for the management of autoimmune bullous diseases during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e302‐e303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abdollahimajd F, Shahidi‐Dadras M, Robati RM, Dadkhahfar S. Management of pemphigus in COVID‐19 pandemic era: a review article. Archiv Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8(1):e51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown AE, Motaparthi K, Hsu S. Rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulin as alternatives to long‐term systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of pemphigus: a single center case series of 63 patients. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23(12). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feldman R. Paradoxical worsening of pemphigus vulgaris following rituximab therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(3):858‐859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.