Abstract

Aims

To determine if the frequency of severe diabetic ketoacidosis at presentation of new‐onset type 1 diabetes to an Australian tertiary centre increased during the initial period of restrictions resulting from the COVID‐19 pandemic (March to May 2020).

Methods

Data were collected on presentations of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes as well as on all paediatric presentations to the emergency department of a tertiary centre between 2015 and 2020. Data from the period of initial COVID restrictions in Australia (March to May 2020) were compared to the period March to May of the previous 5 years (pre‐pandemic periods).

Results

The number of new diagnoses of type 1 diabetes was comparable in the pandemic period and pre‐pandemic periods (11 in 2020 vs range 6–10 in 2015–2019). The frequency of severe diabetic ketoacidosis was significantly higher in the pandemic period compared to the pre‐pandemic periods (45% vs 5%; P <0.003), odds ratio 16.7 (95% CI 2.0, 194.7). The overall frequency of diabetic ketoacidosis was also significantly higher during the pandemic period (73% vs 26%; P <0.007), odds ratio 7.5 (95% CI 1.7, 33.5). None of the individuals tested positive for COVID‐19. Presentations of people aged <18 years to the emergency department decreased by 27% in the pandemic period compared to the average of the pre‐pandemic periods (4799 vs 6550; range 6268 to 7131).

Conclusions

A significant increase in the frequency of severe diabetic ketoacidosis at presentation of type 1 diabetes was observed during the initial period of COVID‐19 restrictions. We hypothesize that concern about presenting to hospital during a pandemic led to a delay in diagnosis. These data have important implications for advocacy of seeking healthcare for non‐pandemic‐related conditions during a global pandemic.

What's new?

Diabetic ketoacidosis is an avoidable complication of type 1 diabetes, associated with significant morbidity and, rarely, mortality.

During COVID‐19 restrictions, healthcare utilization has changed significantly.

We report a significant increase in the frequency of severe diabetic ketoacidosis at presentation of new‐onset type 1 diabetes during the COVID‐19 pandemic at our tertiary centre.

1. INTRODUCTION

A global pandemic requires a health system response that directs limited resources to those most in need. The Director General of the WHO formally declared the outbreak of novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) to be a 'Public Health Emergency of International Concern' on 30 January 2020, and issued a set of temporary recommendations 1 . In Australia, the Prime Minister activated the 'Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus' 2 on 27 February 2020. The national plan outlined a strategy to reduce disease transmission and reduce the burden on the healthcare system. The first death attributable to COVID‐19 in Australia was reported on 1 March 3 . Restrictions enacted in Australia included school shutdowns and the closure of non‐essential businesses, while the majority of outpatient health appointments were conducted by telehealth. These restrictions successfully flattened the curve with the expected surge of COVID‐19 cases and uncontrolled community spread not seen in Australia during the time period described in this study. However, concern has emerged that, with fewer presentations to general practitioners and emergency departments 4 , other serious health concerns may have gone undiagnosed.

The prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in the paediatric population in Australia was recently reported as 24.5% 5 . DKA is an avoidable complication if symptoms and signs of diabetes mellitus are recognized early 6 . DKA places increased burden on the healthcare system and may require intensive care support in tertiary care settings for management. Additionally the presence of DKA at diagnosis has been associated with poor long‐term glycaemic control 7 . During a pandemic, it is important to minimize avoidable admissions to intensive care units when resources may be limited. Emerging research during the COVID‐19 pandemic has shown an increase in children with type 1 diabetes presenting with DKA in countries such as Italy 8 and the USA 9 . A recent study of the German population found the frequency of severe DKA was significantly higher during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and that children under the age of 6 years were at the highest risk 10 .

We report one Australian centre’s experience of presentations of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in a paediatric cohort during the COVID‐19 pandemic restrictions (March to May inclusive) compared to pre‐pandemic presentations in the March to May periods of the years 2015 to 2019.

2. PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

All children and adolescents aged <18 years with the initial diagnosis of type 1 diabetes treated at the John Hunter Children’s Hospital between 1 January 2015 and 31 May 2020 were identified from the hospital paediatric endocrine database and digital medical records. Age, date of diagnosis, HbA1c, initial venous blood gas result (pH, bicarbonate and glucose), C‐peptide, type 1 diabetes‐associated antibody status (presence of glutamic acid decarboxylase, islet antigen 2, islet cell and insulin antibodies) and the results of COVID‐19 tests were collected. In addition, the total number of presentations of children and young people aged <18 years to the John Hunter Hospital Emergency Department was collected for the March to May period in 2015 to 2020.

We defined data collected from 1 March 2020 to 31 May 2020 as the ‘pandemic period’ and the corresponding March to May periods in the 5 years prior to this as ‘pre‐pandemic’ conditions.

Diabetic ketoacidosis was defined as a venous pH <7.3 on presentation, with severe DKA represented by a pH <7.1 as per the 2018 International Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) guidelines 11 . A diagnosis of type 1 diabetes was defined as the presence of DKA or the presence of hyperglycaemia and autoantibodies associated with type 1 diabetes 12 .

Odds ratios, Fisher’s exact test and anova were used to test for differences between the pandemic and pre‐pandemic groups.

2.1. Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the Hunter New England Health Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: AU202006‐10).

3. RESULTS

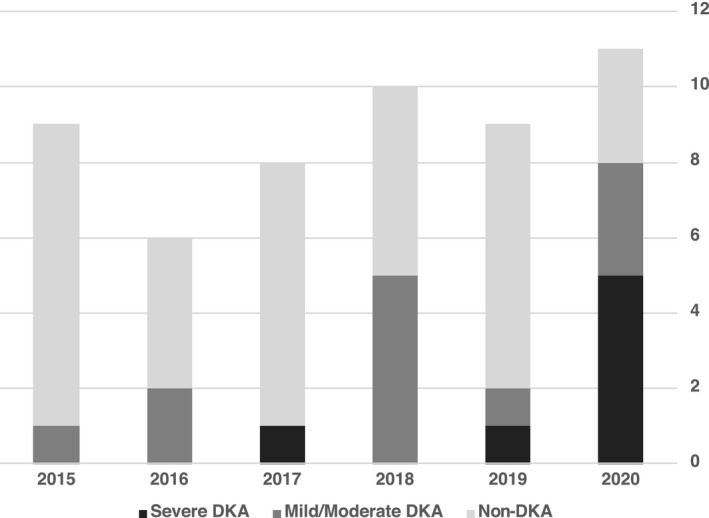

The age of onset, gender, total presentations and classification by severity of DKA are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1 for each of the March to May periods in 2015 to 2020. Data collection was complete, with no missing data. The numbers of new presentations of type 1 diabetes in the March to May period across 2015 to 2020 were fairly consistent; the pre‐pandemic number ranged from 6 to 10 (median 9) across 2015 to 2019, compared with 11 in 2020. There was no significant difference in age or gender across the groups.

Table 1.

Demographic details, initial investigations and number of presentations by severity of children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes for March to May, 2015 to 2020

| New diagnoses of type 1 diabetes, March–May | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | P a | |||||||

| Total | 11 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 9 | NS | ||||||

| Demographics | |||||||||||||

| Age, years | 8.0±4.3* | 7.9±4.0 | 10.2±4.9 | 9.1±4.2 | 10.2±5.4 | 8.4±5.3 | NS | ||||||

| Male, % | 27 | 56 | 50 | 63 | 50 | 33 | NS | ||||||

| Initial investigations | |||||||||||||

| pH | 7.16±0.19 | 7.32±0.13 | 7.27±0.12 | 7.35±0.11 | 7.32±0.15 | 7.33±0.07 | <0.001 | ||||||

| HCO3‐ | 10.9±9.4 | 18.0±7.4 | 15.6±8.0 | 21.9±6.7 | 17.3±7.1 | 19.1±6.8 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Glucose | 27.0±7.4 | 21.6±6.8 | 25.9±7.1 | 16.5±7.7 | 24.7±10.2 | 25.6±10.9 | <0.05 | ||||||

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 112±31 | 114.2±41 | 101±31 | 91.9±34 | 90.7±23 | 109±32 | NS | ||||||

| HbA1c, % | 12.3±2.7 | 12.1±3.2 | 11.4±2.4 | 10.6±3.1 | 10.5±2.1 | 12.0±2.8 | NS | ||||||

| COVID PCR positive | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||||||

| Presentations by severity, n (%) | |||||||||||||

| Non‐DKA | 3 (27) | 7 (78) | 5 (50) | 7 (88) | 4 (67) | 8 (89) | <0.05 | ||||||

| Mild/moderate DKA | 3 (27) | 1 (11) | 5 (50) | 0 | 2 (33) | 1 (11) | NS | ||||||

| Severe DKA | 5 (45) | 1 (11) | 0 | 1 (12%) | 0 | 0 | <0.003 | ||||||

Abbreviations: DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; NS, non‐significant.

Note: Values are mean ± sd, unless otherwise indicated.

Testing pandemic period against the combined (2015–2019) pre‐pandemic periods.

FIGURE 1.

Presentations of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes for March to May in 2015 to 2020. DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis.

The frequency of severe DKA at the time of new type 1 diabetes diagnosis was significantly higher during the period of pandemic restrictions compared to pre‐pandemic (45% vs 5%; P <0.003), odds ratio of 16.7 (95% CI 2.0, 194.7). The frequency of DKA (mild, moderate or severe DKA) was also significantly higher during the period of pandemic restrictions compared to pre‐pandemic conditions (73% vs 26%; P <0.007), odds ratio 7.5 (95% CI 1.7, 33.5). Initial pH, bicarbonate and glucose levels were significantly different in the pandemic group compared to the pre‐pandemic group (P <0.001 for pH and bicarbonate, P <0.05 for glucose). No COVID‐19‐positive cases were identified.

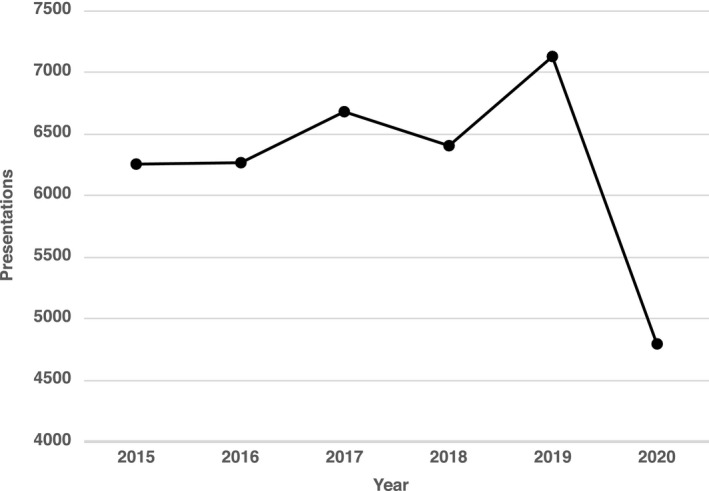

The number of presentations per month of people aged <18 years to the John Hunter Hospital Emergency Department for the March to May period from 2015 to 2020 is shown in Fig. 2. During the pandemic period the number of presentations was 4799 whereas in the 5 years prior the average was 6550 (4799 vs 6550; range 6268 to 7131; P <0.01), a difference of 27%.

FIGURE 2.

Annual presentations per month of patients aged <18 years to John Hunter Hospital Emergency Department for March to May in 2015 to 2020.

4. DISCUSSION

This study reports a significant increase in the frequency of children and adolescents presenting with severe DKA at onset of type 1 diabetes during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The reason for this is unclear. This was not attributable to COVID‐19 infection in the individuals. However, we hypothesize that presentations with new‐onset type 1 diabetes may have been delayed as a result of concern regarding COVID‐19 and the restrictions put in place to combat the COVID‐19 pandemic. During the pandemic period, people were advised to minimize contact with others. Children had less contact with people outside of their primary household, with online learning rather than face‐to‐face schooling, a reduction in contact with friends and family and an increase in virtual medical appointments. Unemployment rates rose and many workers had to adapt to working from home. Disruption to everyday routine could easily have led to the symptoms of type 1 diabetes being missed.

Additionally, the media showed images of people lined up outside hospitals to be tested for COVID‐19 and overseas infection rates and deaths were widely reported. It is possible that people felt that going to their doctor or the emergency department would have placed them at risk of contracting COVID‐19. This is supported by the fact that emergency department presentations to the John Hunter Children’s Hospital fell during this time period.

The increase in presentations of children and adolescents with severe DKA at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes during the COVID‐19 pandemic is a major concern. Not only is severe DKA life‐threatening, but it also requires the use of intensive care beds and resources during a period of potential high demand.

Previous research has shown that delayed recognition of type 1 diabetes symptoms is associated with DKA at disease onset 6 . However, early diagnosis of type 1 diabetes requires people to have contact with health professionals and present to hospitals. Interventions aimed at raising community awareness of the signs and symptoms of type 1 diabetes have been shown to reduce the frequency of DKA at diagnosis 13 , 14 . During a pandemic where schools are in shutdown and many primary care consultations occur via telehealth, alternative ways of raising awareness need to be considered. It is vital that in the eventuality of a subsequent wave of COVID‐19, strategies are implemented in order to avoid a similar increase in severe DKA. These could include social media campaigns, traditional media advertising, mailouts or advertising in local primary health services.

This observational study adds to the limited existing literature describing an increased frequency of severe DKA during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Although this study reports the experience of a single centre, the John Hunter Children’s Hospital Diabetes Centre provides care for all children with type 1 diabetes over the large geographic region of Newcastle and the Greater Hunter. Our experience during the period of pandemic restrictions was anomalous in comparison with the preceding 5 years at our centre. The results reported in this study are likely to be representative of other Australian tertiary centres, most of which have experienced some degree of lockdown. Performing similar studies in centres with differing case rates of COVID‐19 and severity of restrictions enacted would help determine if our experience is universal.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size, which precludes stratified analyses and increases the chance of type II errors. This study is hypothesis‐generating; additional studies that evaluate the reasons for delayed presentations of type 1 diabetes could be used to target campaigns more effectively to reduce this delay.

In summary, in the present study we report a significant increase in presentations of severe DKA in a paediatric population with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes during the COVID‐19 pandemic when social distancing restrictions were enacted. This illustrates the need to encourage children and their families to continue to seek and receive healthcare for non‐pandemic‐related health concerns during a global pandemic.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Michael Anscombe, Director of Paediatric Emergency, and the John Hunter Children’s Hospital Paediatric Emergency Department team for their assistance in data collection and care of acutely unwell children with type 1 diabetes. The authors would also like to thank Prof. Patricia Crock, Dr Komal Vora and the John Hunter Children’s Hospital Paediatric Diabetes team for caring for children with type 1 diabetes in the Hunter region. The authors would particularly like to acknowledge the children and families cared for by the John Hunter Children’s Hospital.

Lawrence C, Seckold R, Smart C, et al. Increased paediatric presentations of severe diabetic ketoacidosis in an Australian tertiary centre during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Diabet. Med. 2021;38:e14417. 10.1111/dme.14417

Funding information

None.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) [Internet]. Available at https://www.who.int/news‐room/detail/30‐01‐2020‐statement‐on‐the‐second‐meeting‐of‐the‐international‐health‐regulations‐(2005)‐emergency‐committee‐regarding‐the‐outbreak‐of‐novel‐coronavirus‐(2019‐ncov). Last accessed 28 May 2020.

- 2. Australian Government Department of Health. Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19) [Internet]. 2020 Apr. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian‐health‐sector‐emergency‐response‐plan‐for‐novel‐coronavirus‐covid‐19. Last accessed 28 May 2020.

- 3. Government of Western Australia Department of Health. WA confirms first novel Coronavirus death [Internet]. 2020 Available at https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/en/Media‐releases/2020/WA‐confirms‐first‐novel‐Coronavirus‐death. Last accessed 1 June 2020.

- 4. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. RACGP launches nationwide campaign to stop people neglecting their health due to COVID‐19 [Internet]. 2020. Available at https://www.racgp.org.au/gp‐news/media‐releases/2020‐media‐releases/april‐2020/racgp‐launches‐nationwide‐campaign‐to‐stop‐people. Last accessed 29 May 2020.

- 5. Cherubini V, Grimsmann JM, Åkesson K, et al. Temporal trends in diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of paediatric type 1 diabetes between 2006 and 2016: results from 13 countries in three continents. Diabetologia [Internet]. 2020 May 8 Available at http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00125‐020‐05152‐1. Last accessed 5 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bui H, To T, Stein R, Fung K, Daneman D. Is Diabetic Ketoacidosis at Disease Onset a Result of Missed Diagnosis? J Pediatr. 2010;156:472–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duca LM, Wang B, Rewers M, Rewers A. Diabetic Ketoacidosis at Diagnosis of Type 1 Diabetes Predicts Poor Long‐term Glycemic Control. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1249–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rabbone I, Schiaffini R, Cherubini V, et al. Has COVID‐19 Delayed the Diagnosis and Worsened the Presentation of Type 1 Diabetes in Children? Diabetes Care. 2020;dc201321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cherubini V, Gohil A, Addala A, et al. Unintended Consequences of COVID‐19: Remember General Pediatrics. J Pediatr. 2020;223:197–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kamrath C, Mönkemöller K, Biester T, et al. Ketoacidosis in Children and Adolescents With Newly Diagnosed Type 1 Diabetes During the COVID‐19 Pandemic in Germany. JAMA. 2020;324:801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolfsdorf JI, Glaser N, Agus M, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19:155–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mayer‐Davis EJ, Kahkoska AR, Jefferies C, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Definition, epidemiology, and classification of diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19:7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vanelli M, Chiari G, Ghizzoni L, Costi G, Giacalone T, Chiarelli F. Effectiveness of a prevention program for diabetic ketoacidosis in children. An 8‐year study in schools and private practices. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. King BR, Howard NJ, Verge CF, et al. A diabetes awareness campaign prevents diabetic ketoacidosis in children at their initial presentation with type 1 diabetes: Population awareness prevents DKA. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13:647–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]