Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this report is to describe the successful management of plantar fasciitis (PF) using only extracorporeal shockwave therapy.

Clinical Features

A 26-year-old male former athlete presented with insidious right posterior medial foot pain of 3 months’ duration. He reported a past history of similar symptoms 12 years previously and was successfully treated with tape, ice, and electric stimulation. For the current episode, he attempted to manage with orthotics, motor nerve stimulation, and ice, and when that was insufficient, he sought care in our clinic. Initial history and evaluation found provocation of pain and functional limitations while wearing dress shoes, running, and playing basketball. Examination found palpatory tenderness at the medial aspect of the distal right calcaneus, and pain with right ankle dorsiflexion. Radiographs were unremarkable. Patient presentation and exam findings supported a working diagnosis of PF.

Intervention and Outcomes

Treatment was applied with a Richard Wolf WellWave low-energy shockwave therapy unit with focused dosage of 4000 shock pulsations at 10-mm depth to the site of pain. Treatment was applied 11 × over 5 weeks, after which the patient reported a complete resolution of pain and resumption of all activities.

Conclusion

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy appeared to be an effective treatment approach for the management of this patient's PF.

Key Indexing Terms: Sound; Acoustic Stimulation; Acoustics; Fasciitis, Plantar

Introduction

Plantar fasciitis (PF) is the most common cause of foot pain,1 affecting 10% of the general population, and is responsible for 11% to 15% of all foot pain requiring professional care.2-6 More than 1 million patients per year are treated in US medical offices for plantar fasciitis.7 The exact etiology of plantar fasciitis is unknown6; however, it may be the result of repeated microinjuries and recurrent irritation of the plantar aponeurosis along the plantar fascia insertion at the medial calcaneal tubercle, resulting in local pain with weight bearing.8 Histology studies show chronic degeneration, and not an acute inflammatory process.1 Predisposing factors leading to PF include obesity,1,3,6,9, 10, 11, 12 excessive pronation,1,9 running,4,6,10,13 bone spur,2 reduced plantar fascia elasticity,3 decreased dorsiflexion,1,13 and prolonged standing.3,13

The typical presentation is piercing, throbbing, or burning plantar heel pain.1 It is most severe upon taking the first steps in the morning,1,3, 4, 5, 6,9,10,14,15 for the initial steps after a rest,3 with prolonged standing,4 or with sustained loading at the end of the day.1,8,10 Examination typically demonstrates medial calcaneal tubercle tenderness4,13 and loss of dorsiflexion.13 Passive toe extension can increase heel pain in severe cases.5,13

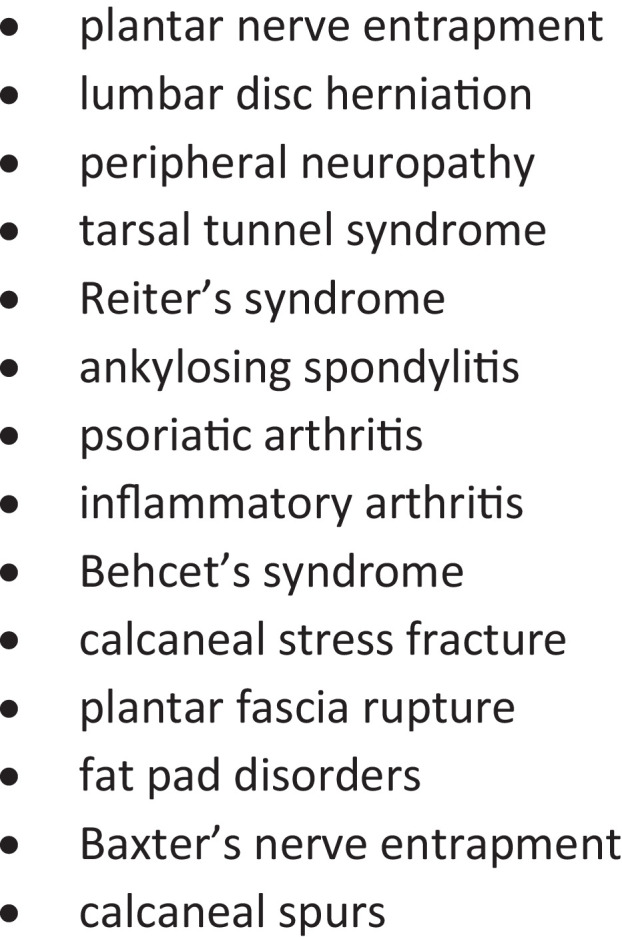

The diagnosis is typically based on history and examination.1,3,4 Imaging should be considered to rule out other conditions (Fig 1) when the diagnosis is not clear.9 Common radiographic findings include inferior calcaneal osteophytes, although not necessarily directly related to heel pain.14

Fig 1.

Patients typically show a clinical response within 6 weeks of tier 1 treatments,1 such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),1,13,16 orthotics,1,7,13,17,18 taping,17,18 limited physical activity,1,13,16 insole cushions,16 and stretches.1,7,13,16, 17, 18 Although tier 1 treatments continue for patients whose symptoms persist after 6 weeks, tier 2 treatments including corticosteroid injections,1,3,13,17,18 physiotherapy,1,17 and night splints are added.1,17 Plantar fasciitis is generally a self-limiting condition,7,8,14 but 10% of patients do not respond to tier 1 or tier 2 treatments.2,3,7,9

Limited resolution after 6 months of tier 1 and 2 treatments leads to recommendation of tier 3 treatments including extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) and surgery in this model.1,2 Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2000,1 ESWT uses sound waves aimed at the plantar fascia enthesis.19 The exact effect of this therapy is not well understood.14,16 Proposed mechanisms for the effect of ESWT are increasing blood flow or nitric oxide production to stimulate an immune reaction or suppress an inflammatory response,16,19 causing reinjury to prompt healing,19 blocking the nociceptive pathways via the pulses hitting the nerves,3,19 releasing nociceptor inhibiting enzymes,7 neovascularization,3,16 reduction of calcification, and denervation.6 The purpose of this study is to present a case of PF that resolved after application of only ESWT in a chiropractic office. This is the first case of chiropractic management of PF via ESWT found in the literature.

Case Study

A 26-year-old male former athlete presented with right foot pain that started 3 months earlier. He reported a similar episode of pain at age 14 that resolved after 3 months of treatment with tape, ice, and electrical stimulation. The current episode was reported as a sharp, localized pain at the medial right distal calcaneus, predominantly with the first steps upon rising in the morning, rated 6 of 10 on the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS). After the initial morning steps, the pain decreased to a feeling of pressure throughout the day. His pain was aggravated by orthotics, hard-sole dress shoes, running more than a mile, or playing basketball. Self-prescribed home care including interferential motor nerve stimulation, and ice offered modest, temporary pain relief, allowing him to sleep better. The patient noted that the self-care had marginal positive effect on his condition overall. He substituted tennis shoes for dress shoes, reduced his running from 13 miles to 1 mile, and limited his work schedule. He sat several hours a day as a graduate student followed by standing for long hours as a personal trainer, and despite alterations to these activities, he continued to be impaired by pain. A baseline assessment of functional disability was established using the Foot Function Index with a score of 45 of 230.

Physical examination found that palpation of the medial aspect of the distal calcaneus caused a startled withdrawal of the foot, and ankle dorsiflexion reproduced the patient's symptoms. Radiographs (Fig 2) revealed an incidental finding of minimal degenerative osteophyte formation at the anterior tibiotalar joint. These findings supported a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis.

Fig 2.

Lateral radiographic view of right foot was unremarkable for pathology.

Treatments were administered using a Richard Wolf ELvation WellWave low energy ESWT unit (Fig 3). Ultrasound gel was used to keep the applicator in contact with the skin. At each visit, 4000 focused shock waves were administered to patient tolerance with a flux intensity of 0.403 mJ/mm2 at a frequency of 8 Hz with a 10-mm-depth gel pad. The sessions were held twice a week with a total of 11 sessions over 5 weeks. Each treatment was performed by locating a tender point through palpation and confirmed by the patient acknowledging moderate pain. Pulses were applied by positioning the applicator at the most tender point for 10 to 20 seconds (Fig 4) and then moving it to the next tender location. If site of application was not painful, the applicator was repositioned at the next painful site. At each office visit, the activities of daily living (ADLs) and VRS were assessed. After 5 weeks and 11 ESWT treatments, he was fully engaged in all ADLs, his VRS was 0 of 10, and his Foot Function Index score was 5 of 230 (Fig 5, Fig 6). The patient gave consent for the publication of this report.

Fig 3.

The Richard Wolf ELvation WellWave ESWT unit. ESWT, extracorporeal shockwave therapy.

Fig 4.

Indicates head focus and placement for ESWT of PF. ESWT, extracorporeal shockwave therapy; PF, plantar fasciitis.

Fig 5.

The Foot Functional Index showing improvement. FFI, Foot Functional Index.

Fig 6.

The Verbal Rating Scale showing immediate and sustained improvement. DOS, date of service; VRS, Verbal Rating Scale.

Discussion

The complete resolution of PF in this case of a 26-year-old man supports ESWT as an appropriate early intervention for this condition. Many studies recommend shockwave for chronic PF after a refractory response to conservative care and just before surgery.12,14 However, our findings align with others20,21 that early-application ESWT may be an effective treatment before the condition becomes chronic, defined as greater than 6 months.20 Our study demonstrates another example that this modality can be used safely and effectively for pain reduction and functional recovery.5,6,16,22,23

Our patient's pain and function rapidly improved with some discomfort related to the treatment. He reported increased pain during and up to 3 hours after the first 5 treatments. Pain after ESWT application has been previously studied in a trial of 60 patients.1 This type of transient pain is a common side effect with ESWT3,4 and can cause a cessation of care,4 but it did not deter this patient from ongoing care, and his recovery was successful. Although this patient did not have any significant adverse reactions, rare serious complications such as microfractures and osteonecrosis have been documented.22

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy can allow quicker symptom improvement than conventional physical therapy, including ultrasound and therapeutic exercise.12 Extracorporeal shockwave therapy has been shown to be more effective than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs2 and to have superior outcomes to corticosteroid injections.3,16 In a study by Roca et al, ESWT was demonstrated to have superior outcomes to botulinum injections when both were compared with placebo,19 and steroid injection therapies come with an added risk of plantar fascia rupture.15 Surgery for PF has almost a one-third recurrence rate12 and can result in injury to the posterior tibial nerve, tarsal instability, swelling, long immobilization, delays in returning to daily activities, and calcaneal fracture.3 Extracorporeal shockwave therapy has fewer complications than surgery, a shorter recovery period, and no operative scarring.11

The lack of consensus for a specific ESWT protocol can be frustrating for the practicing provider, and a standardized PF protocol regarding frequency, dose, and pulses per session would be a beneficial addition to the literature.21 There is wide variance in the current literature: from a single session of 3800 shocks at 0.34 mJ/mm2 to 3 weekly sessions of 4000 shocks at 0.08 mJ/mm2 to 3 monthly sessions of 1500 shocks at 0.12 mJ/mm2.21 We chose the machine's default setting of 4000 shocks, and 0.403 mJ/mm2 because that was within the patient's tolerance.

Limitations

Weaknesses of this study are reliance on student records from a teaching clinic and lack of a follow-up assessment. The details of the patient's home care and work limitations were not recorded in the record, as well as amount of time or variance in ADLs before presenting for care. The sustainability of the patient's improvement may have been short term, as there was no long-term follow-up. This case study followed only 1 patient, so results cannot be generalized to the broader population of PF patients. The natural course of PF is not well understood,24 so it remains possible that the patient recovered spontaneously rather than from our therapeutic intervention.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated resolution of PF with the early application of ESWT in a chiropractic teaching clinic. No serious adverse effects occurred with treatment. Further, more rigorous study on the early application of ESWT and most effective treatment protocols on larger groups of PF patients is recommended.

Practical Applications.

-

•

This article describes the presentation of a common foot disorder.

-

•

This study relates how shockwave helps PF. It discusses indications, protocols, and potential complications.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gregory Snow, DC, for his editorial assistance.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): K.T.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): K.T.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): K.T., J.B.S.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): K.T.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): K.T., J.B.S.

Literature search (performed the literature search): K.T., J.B.S.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): K.T., J.B.S.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): K.T., J.B.S.

References

- 1.Ulusoy A, Cerrahoglu L, Orguc S. Magnetic resonance imaging and clinical outcomes of laser therapy, ultrasound therapy, and extracorporeal shock wave therapy for treatment of plantar fasciitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;56(4):762–767. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lou J, Wang S, Liu S, Xing G. Effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy without local anesthesia in patients with recalcitrant plantar fasciitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96(8):529–534. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hocaoglu S, Vurdem UE, Cebicci MA, Sutbeyaz ST, Guldeste Z, Yunsuroglu SG. Comparative effectiveness of radial extracorporeal shockwave therapy and ultrasound-guided local corticosteroid injection treatment for plantar fasciitis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2017;107(3):192–199. doi: 10.7547/14-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roerdink RL, Dietvorst M, van der Zwaard B, van der Worp H, Zwerver J. Complications of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in plantar fasciitis: systematic review. Int J Surg. 2017;46:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.08.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arslan A, Koca TT, Utkan A, Sevimli R, Akel I. Treatment of chronic plantar heel pain with radiofrequency neural ablation of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve and medial calcaneal nerve branches. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(4):767–771. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin M, Chen N, Huang Q. New and accurate predictive model for the efficacy of extracorporeal shock wave therapy in managing patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(12):2371–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chew KT, Leong D, Lin CY, Lim KK, Tan B. Comparison of autologous conditioned plasma injection, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, and conventional treatment for plantar fasciitis: a randomized trial. PM R. 2013;5(12):1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.08.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozan F, Koyuncu S, Gurbuz K, Oncel ES, Altay T. Radiofrequency thermal lesioning and extracorporeal shockwave therapy: a comparison of two methods in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Spec. 2017;10(3):204–209. doi: 10.1177/1938640016675408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin MC, Ye J, Yao M. Is extracorporeal shock wave therapy clinical efficacy for relief of chronic, recalcitrant plantar fasciitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo or active-treatment controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(8):1585–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee TL, Marx BL. Noninvasive, multimodality approach to treating plantar fasciitis: a case study. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2018;11(4):162–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maki M, Ikoma K, Imai K. Correlation between the outcome of extracorporeal shockwave therapy and pretreatment MRI findings for chronic plantar fasciitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25(3):427–430. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2014.978526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grecco MV, Brech GC, Greve JM. One-year treatment follow-up of plantar fasciitis: radial shockwaves vs. conventional physiotherapy. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013;68(8):1089–1095. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(08)05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monto RR. Platelet-rich plasma and plantar fasciitis. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2013;21(4):220–224. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e318297fa8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Razzano C, Carbone S, Mangone M, Iannotta MR, Battaglia A, Santilli V. Treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis with noninvasive interactive neurostimulation: a prospective randomized controlled study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;56(4):768–772. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louwers MJ, Sabb B, Pangilinan PH. Ultrasound evaluation of a spontaneous plantar fascia rupture. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89(11):941–944. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181f711e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eslamian F, Shakouri SK, Jahanjoo F, Hajialiloo M, Notghi F. Extra corporeal shock wave therapy versus local corticosteroid injection in the treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis, a single blinded randomized clinical trial. Pain Med. 2016;17(9):1722–1731. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen BM. Trigger point therapy and plantar heel pain: a case report. Foot (Edinb) 2010;20(4):158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akhbari B, Salavati M, Ezzati K, Mohammadi Rad S. The use of dry needling and myofascial meridians in a case of plantar fasciitis. J Chiropr Med. 2014;13(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roca B, Mendoza MA, Roca M. Comparison of extracorporeal shock wave therapy with botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(21):2114–2121. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1114036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena A, Hong BK, Yun AS, Maffulli N, Gerdesmeyer L. Treatment of plantar fasciitis with radial soundwave “early” is better than after 6 months: a pilot study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;56(5):950–953. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Speed C. A systematic review of shockwave therapies in soft tissue conditions: focusing on the evidence. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(21):1538–1542. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erduran M, Akseki D, Ulusal AE. A complication due to shock wave therapy resembling calcaneal stress fracture. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(4):599–602. doi: 10.1177/1071100712470917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheuer R, Friedrich M, Hahne J. Approaches to optimize focused extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) based on an observational study of 363 feet with recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Int J Surg. 2016;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cutts S, Obi N, Pasapula C, Chan W. Plantar fasciitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94(8):539–542. doi: 10.1308/003588412X13171221592456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]