Abstract

Introduction

Cervical cancer screening ceases between the ages of 60 and 65 in most countries. Yet, a relatively high proportion of cervical cancers are diagnosed in women above the screening age. This study will evaluate if screening of women aged 65–69 years may result in increased detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN2+) compared with women not invited to screening. Invited women may choose between general practitioner (GP)-based screening or cervico-vaginal self-sampling. Furthermore, the study will assess if self-sampling is superior to GP-based screening in reaching long-term unscreened women.

Methods and analysis

This population-based non-randomised intervention study will include 10 000 women aged 65–69 years, with no record of a cervical cytology sample or screening invitation in the 5 years before inclusion. Women who have opted-out of the screening programme or have a record of hysterectomy or cervical amputation are excluded. Women residing in the Central Denmark Region (CDR) are allocated to the intervention group, while women residing in the remaining four Danish regions are allocated to the reference group. The intervention group is invited for human papillomavirus-based screening by attending routine screening at the GP or by requesting a self-sampling kit. The reference group receives standard care which is the opportunity to have a cervical cytology sample obtained at the GP or by a gynaecologist. The study started in April 2019 and will run over the next 4.5 years. The primary outcome will be the proportion of CIN2+ detected in the intervention and reference groups. In the intervention group, the proportion of long-term unscreened women attending GP-based screening or self-sampling will be compared.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been submitted to the Ethical Committee in the CDR which deemed that the study was not notifiable to the Committee and informed consent is therefore not required. The study is approved by the Danish Data Protection Regulation and the Danish Patient Safety Authority. Results will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

Keywords: epidemiology, cytopathology, preventive medicine, public health, gynaecology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This population-based intervention study is the first to evaluate if expanding the upper screening age to include women aged 65–69 years and inviting them to choose between general practitioner (GP)-based screening or self-sampling will result in increased detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse compared with existing practice (ie, no screening).

This study is the first to evaluate if self-sampling is superior to GP-based screening in reaching long-term unscreened women aged 65–69 years.

The risk of information bias and selection problems are minimised by using high-quality Danish registries and a population-based design.

The study design entails a risk of confounding due to the lack of randomisation.

Introduction

Cervical cancer screening ceases between the ages of 60 and 65 in most western countries.1–3 There is no solid evidence about which age and with which criteria to cease screening,1 4–6 but the cessation of screening in older women is often justified by a low prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) in women ≥55 years7 8 and by a concern that the harms of continuing screening may outweigh potential benefits.2 Many countries with long-established screening programmes, including Denmark, experience a second incidence peak of cervical cancer around the age of 75–80 years,9 10 with a hysterectomy-corrected incidence rate of 29.4 per 100 000 person-years in women aged 75–79.11 These older women are more often diagnosed with advanced-stage disease, and mortality due to cervical cancer is high as compared with younger women.12 13 It has been hypothesised that the incidence peak at older ages could be a result of a mid-life change of sexual partners or reactivation of a latent HPV infection as the immune system weakens with age.14–17 However, a recent Danish study of HPV DNA prevalence in women aged 69 and above showed no increase in prevalence that could explain the cervical cancer peak at older ages.18 The authors stated that this result may be explained by the fact that an HPV infection may become undetectable at a late stage in the oncogenic process.18 19 It has also been hypothesised that the current peak in older ages could be attributed to an insufficient screening history in older birth cohorts.20 Whatever the reason, the increasing female life expectancy (at age 65 years it is about 20 additional years) has raised the question if the upper age limit for screening should be extended to 69 or 70 years.10 21 22 Case–control studies have reported benefits of cervical cytology screening at older ages with respect to reduced incidence and mortality,7 23–26 even among previously screened women.4 However, a prospective evaluation of HPV-screening at ages 65–69 in a population-based intervention study including a reference group is missing.

The effectiveness of cervical cancer screening among older women will depend on the participation rate and, in particular, the ability to reach long-term unscreened women, as these women have a pronounced risk of cancer.6 27 Currently, participation in routine screening decreases with increasing age leaving a relatively high proportion of older women under-screened.10 A potential solution to this challenge could be to offer older women a self-sampling kit for HPV testing (self-sampling). Self-sampling is an accurate and well-accepted screening method, proven superior to physician-based screening in reaching long-term unscreened women.28 29 Yet, it remains unknown whether an older screening population will benefit from a self-sampling offer.

Objectives

This study will evaluate if expanding the upper screening age to include women aged 65–69 years and inviting them to choose between general practitioner (GP)-based screening or self-sampling results in increased detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN2+) compared with existing practice where women in this age group are not invited to routine screening. Furthermore, it will be assessed whether self-sampling is better than GP-based screening in reaching long-term unscreened women.

Hypotheses

We hypothesise that expanding the upper screening age will result in increased detection of CIN2+ cases and, long-term, potentially reduce the cervical cancer incidence compared with women not invited to screening. Finally, we hypothesise that self-sampling will be superior to GP-based screening in reaching long-term unscreened women.

Methods and analysis

Setting

Organised cervical cancer screening was introduced in parts of Denmark in the 1960s and became nationwide in the late 1990s.30 31 Screening in Denmark is currently organised by the five regions (North, Central, South, Zealand and Capital) following national guidelines.31 32 Cervical cancer screening is centralised to one or a few pathology departments in each region.31 Danish women are invited to schedule an appointment with their GP for liquid-based cytology screening every third year when aged 23–49 years and every fifth year when aged 50–64 years31. Since 2012, women aged 60–64 years have been screened with an HPV DNA-check-out test, after which HPV negative women can exit the programme without consideration of their screening history.32 Outside the organised programme, women can have a cervical cytology sample taken by a GP or a gynaecologist opportunistically or due to clinical symptoms at any time. In Denmark, cervical cancer screening, including clinical follow-up and treatment, is free of charge.31

The intervention in this study will be run by the Department of Public Health Programmes, Randers Regional Hospital in the Central Denmark Region (CDR). The CDR is the second largest region in Denmark covering approximately one-fourth of the Danish population (1.2 million inhabitants).22 In the CDR, the Department of Public Health Programmes oversees sending screening invitations, reminders and test results, while the Department of Pathology, Randers Regional Hospital handles and analyses all cervical cytology samples.

Call–recall invitation system

The Danish screening programme is based on an integrated call–recall system using data from the invitation module in the nationwide Danish Pathology Databank (DPDB).31 33 34 The Conseillers en Gestion et Informatique (CGI) Institute operates the call–recall system and it is designed so that each region only invites women residing in their catchment area. The call–recall system invites women for screening after the age-specific interval has passed since their latest invitation or cervical cytology sample (whichever came last). Samples obtained opportunistically, symptomatically or as part of surveillance are also recorded in the DPDB and postpone the next invitation. The system also keeps track of women who are ineligible for screening because they have actively opted out of the programme or have had a hysterectomy. The latter registration is rather incomplete and varies between the regions. In detail, the invitation module links cervical cytology data (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine, SNOMED codes: T8×3* and T8×210) from the DPDB’s main pathology module with information about residency and vital status from the Danish Civil Registration System.35 36 Linkage is performed using the unique Civil Personal Registration (CPR) number, which is assigned to every Danish citizen on birth and to residents on immigration.36 The CPR number is used by all citizens for any contact to the Danish healthcare system.

Design and eligibility criteria

This study is a nationwide prospective population-based non-randomised intervention study (ie, a quasi-experimental design).37 Women will consecutively be deemed eligible if they meet the following criteria at the time of inclusion: aged 65–69 years; resident in Denmark for the past 5 years; no record of a cervical cytology sample or invitation in the past 5 years; not registered in the invitation module as having actively opted out of the screening programme or having a record of total hysterectomy or cervical amputation in the Danish National Patient Register.38 Eligible women residing in the CDR will be allocated to the intervention group, while women residing in the other four Danish regions will be allocated to the reference group (figure 1). In the intervention group, the invitation module will be set-up to identify women fitting the inclusion criteria, and simultaneously a comparable list of eligible women in the reference group will be compiled by CGI at the Department of Public Health Programmes’ request. Inclusion started in April 2019 and eligible women will be identified with 6 months intervals until the desired number of women have been included. The follow-up period for the included women will start on the date of the invitation and end at time of death, emigration, cervical amputation, total hysterectomy or end of study. Women that move between the intervention region and reference regions in the follow-up period will subsequently be excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1.

Map of the intervention and reference regions.

Intervention group

Women living in the CDR and therefore eligible for the intervention group will be invited to HPV-based cervical cancer screening by either scheduling an appointment for having a cervical cytology sample collected at their GP or collecting a cervico-vaginal sample themselves in their own home using a self-sampling kit. Women will receive an invitation and an information sheet by digital mail, while those exempted from digital mail as per routine will receive the information by postal mail.39 The invitation explains how to request the self-sampling kit and states that once the woman attends screening it will implicitly represent her consent to store her sample for future quality improvement of the screening programme. A phone number for calling the study investigator to decline this option will be available. Test results, including follow-up recommendations, will be sent to the women by digital or postal mail and the woman’s GP will receive an electronic copy of the test result. Around 98% of all residents in Denmark are listed with a GP.40 As per routine, non-participants will receive up to two reminders at 3 and 6 months postinvitation.31 All information will be in Danish.

Self-sampling kit

The self-sampling kit can be requested by phone or through a study webpage. After receiving the orders in the department, the kit will be mailed to the women within four business days. The kit includes the dry Evalyn brush self-sampling device (Rovers Medical Devices B.V, Oss, Netherlands),41 written and picture-based user instructions on how to collect and mail the self-sample, and a prestamped return envelope addressed to the Department of Pathology, Randers Regional Hospital.42 The acceptability of both the self-sampling device and user instructions has been carefully evaluated in previous studies, although among younger women (30–59 years).43 44

Processing and analysis of samples

In the intervention group, all samples will be prepared, processed and analysed at the Department of Pathology, Randers Regional Hospital according to the routine laboratory protocols. All HPV testing will be performed using the clinically validated and Federal Drug Agency-approved Cobas 4800 DNA test (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland),45 as this is the routine test platform used in the CDR. The test is an automated real-time PCR-based test designed to detect high-risk HPV types: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 6845 46 and is validated for use on SurePath collected samples.47 Results will be reported as (1) HPV negative, (2) HPV positive (HPV16, HPV18 and/ or other HPV types) or (3) invalid.42 All samples with an invalid test result will be re-tested, and the second result will be considered definitive. The Cobas test measures beta-globin as an internal control for sample cellularity, valid sample extraction and amplification.46

As per routine, cervical cytology samples taken by the GPs will be collected using a cervical brush and rinsed in 10 mL SurePath medium (BD Diagnostics, Burlington, North Carolina, USA) and mailed to the Department of Pathology, Randers Regional Hospital for processing and HPV testing. For HPV positive women, reflex cytology testing will be performed on the residual cellular Surepath material. Cytology will be interpreted by cytotechnologists using computer-assisted microscopy and categorised per the Bethesda 2014 grading system as normal; inadequate; atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US); low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL); atypical squamous cells cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H). High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL); squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); atypical glandular cells (AGC), adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS); adenocarcinoma (ACC) and malignant tumour cells. At the laboratory, the Evalyn brush device will be rinsed into 10 mL SurePath medium (BD Diagnostics, Burlington, North Carolina, USA) and processed as previously described.43

From the cervical cytology samples and self-samples, 2 mL of the SurePath medium will be placed in test tubes for HPV testing. The residual purified DNAmaterial from these samples will be stored at −80°C for future extended genotyping and DNA methylation analysis. As part of the study, and only in the intervention group, p16/Ki67 cytology dual staining (CINtec PLUS cytology kit, Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) will be performed consecutively on the residual SurePath cell-pellet obtained from women with an HPV positive cervical cytology sample and sufficient material for cytology testing. The dual staining result will not affect the clinical management of the woman. Except for the dual staining result, all test results will routinely be registered in the DPDB.34

Clinical management

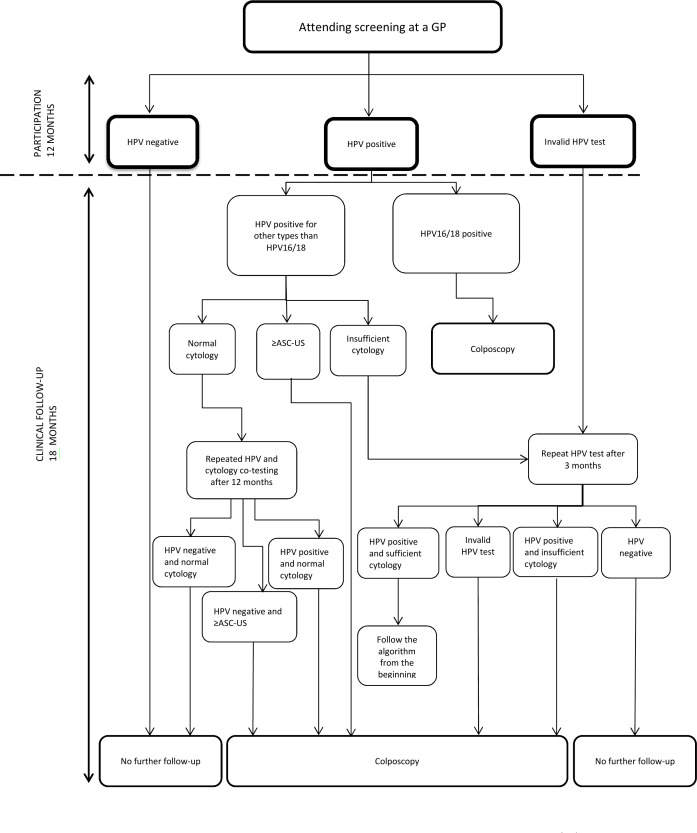

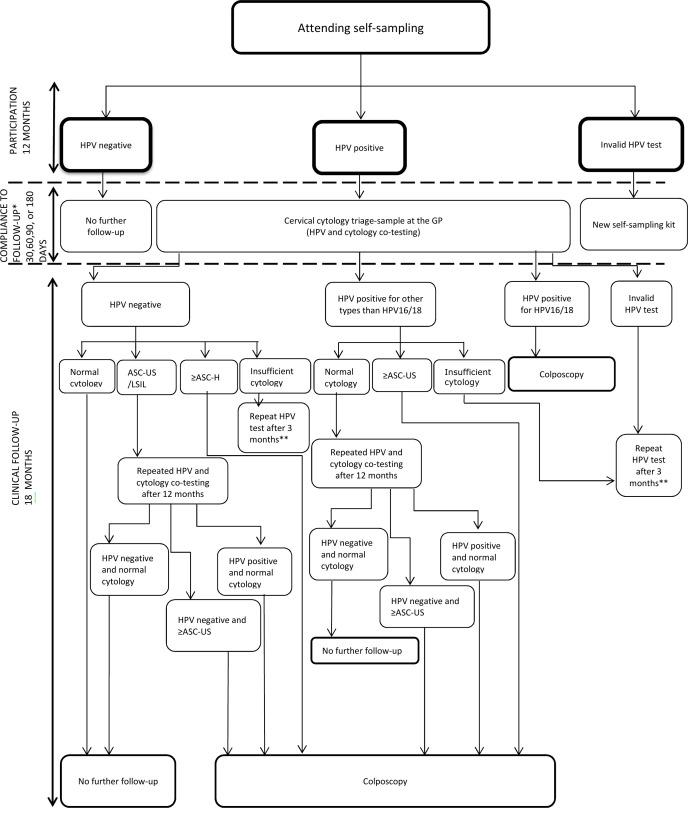

Figures 2 and 3 show the recommended, and therefore, expected clinical management for women in the intervention group, but management may deviate depending on the clinical presentation of the individual woman. The recommendations are in accordance with the routine screening guidelines for 60–64 years old women and the new guidelines for clinical management of older women with dysplasia and HPV.32 48 Women who are positive for HPV16 or 18 AND other types will be managed similar to HPV16/18 positive women.

Figure 2.

Clinical management of women attending screening at a GP. HPV other types than HPV16/18: 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68. ≥ASC-US includes:atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US); low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL); atypical squamous cells cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H); high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion(HSIL); squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); atypical glandular cells (AGC); adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS); adenocarcinoma (ACC) and malignant tumour cells. GP, general practitioner; HPV, human papillomavirus;

Figure 3.

Clinical management of women attending self-sampling. HPVother types than HPV16/18: 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68. ≥ASC-US include: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US); low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL); atypical squamous cellscannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H); high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL); squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); atypical glandular cells (AGC), adenocarcinomain situ (AIS); adenocarcinoma (ACC) and malignant tumour cells. ≥ASC-H include:ASC-H, HSIL, SCC, AGC, AIS, ACC and malignant tumour cells. *Compliance to follow-up among HPV positive self-samplers. **Follows the same algorithm as shown in figure 2 among women having repeating HPV testing after 3 months. GP, general practitioner; HPV, human papillomavirus.

For women attending GP-based screening, those who tested HPV negative will have no further follow-up (figure 2). Women tested positive for HPV16/HPV18 will be referred directly to colposcopy (regardless of the cytology result). Women tested HPV positive for other types than HPV16/18 with ASC-US or more severe cytological abnormalities will be referred to colposcopy, while women with HPV types other than HPV16/18 and normal cytology will undergo repeated cotesting (HPV and cytology) after 12 months and will be referred for colposcopy if either test result is positive.

Figure 3 presents the follow-up recommendations for women attending self-sampling. Women who tested HPV negative in their self-sample will have no further follow-up. Women with an HPV positive self-sample (any genotype) will be advised to have a cervical cytology triage sample taken by their GP within 30 days to evaluate the need for referral to colposcopy. This triage sample will be co-tested with HPV and cytology. Women tested HPV negative with normal cytology will have no further follow-up, while those with ASC-US/LSIL cytology will undergo a repeat cotest (HPV and cytology) after 12 months and will be referred for colposcopy if either test result is positive. Those with ASC-H or more severe abnormalities will be referred for colposcopy. Women with an HPV positive triage cytology sample will follow the same recommendation as described for the GP-based screening (figure 2).

For women referred for colposcopy, cervical punch biopsies will be taken from suspicious areas, supplemented with random biopsies according to Danish guidelines.49 Some women may also undergo a diagnostic conization as part of a clinical ‘see-and-treat’ study.50 Histological examination of the cervical biopsies will be carried out at different local Pathology Departments and graded using the Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) classification as normal (including inflammation and non-specific reactive features), CIN (not specified), CIN grade 1, 2 or 3/AIS, or invasive cancer.

Reference group

Women in the reference group will receive usual care which, for 65–69 years old women, is the opportunity to have a cervical cytology sample obtained at their GP or by a gynaecologist for whatever reason. The women will not receive a screening invitation, but will be assigned individual pseudo screening invitation dates allowing comparison between the groups in our statistical analysis. In the following, the term ‘invitation date’ will be used for both for the ‘true invitation dates’ in the intervention group and ‘pseudo invitation dates’ in the reference group. In all reference regions, samples from this age group are expected to be tested for HPV. Differences across the four regions are found in the HPV assay18 and there may be minor differences in the triage-strategies, which may result in differences in indication for colposcopy referral. However, clinical management of women referred for colposcopy is expected to follow national guidelines as described earlier.48 49

Outcomes

Overview of outcomes and planned comparisons is seen in table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of outcomes and planned comparisons

| Outcome | Comparisons |

| CIN2+ | Intervention vs reference group |

| CIN3+ | Intervention vs reference group |

| Screening participation | Intervention group: self-sampling vs GP-sampling |

| Screening history | Intervention group: self-sampling vs GP-sampling |

| HPV positivity rate | Intervention group: self-sampling vs GP-sampling |

| HPV type distribution | Intervention group: self-sampling vs GP-sampling |

| Cytology results* | Intervention group |

| Compliance to follow-up among HPV positive self-samplers | Intervention group |

| Proportion and results of cervical cytology samples | Reference group |

| Colposcopies and conizations | Intervention vs reference group |

| Cervical cancer incidence | Intervention vs reference group |

*Only available for women with an HPV positive GP-sample or GP-triage sample following an HPV positive self-sample.

CIN2+, CIN2, CIN3/AIS and cancer; CIN3+, CIN3/AIS and cancer; GP, general practitioner; HPV, human papillomavirus.

In both groups, the primary outcome will be the proportion of CIN2+ (CIN2, CIN3/AIS and cancer) detected within 18 months following registration of a cervical cytology sample or self-sample. The proportion of CIN3+ (CIN3/AIS and cancer) will be a secondary outcome. The most severe histological test result will be used if more than one result is available in the follow-up period. Other outcomes in the intervention group will be screening participation measured 12 months after the invitation date, defined by returning a self-sample or having a cervical cytology taken; screening history of participants, stratified by sampling procedure; HPV positivity rate and HPV type distribution in self-samples versus GP-collected cervical cytology samples; cytology results, and the percentage of HPV positive self-samplers undergoing appropriate follow-up. Compliance to follow-up after self-sampling will be defined as attending a GP for a cervical cytology-triage sample within 30, 60, 90 or 180 days after mailing of the test results. The proportion and results of cervical cytology samples obtained among women not invited for screening will be identified in the reference group and measured 12 months postinvitation date. As in another study,2 the primary measure of harms will in both groups be the number of colposcopies/conizations performed, both overall and relatively to ≤CIN1, CIN2, CIN3/AIS and cancers detected within a follow-up period of 18 months after registration of a cervical cytology sample or self-sample. Long-term outcomes will be cervical cancer incidence rates reported by groups at 5 and 10 years post invitation dates. A description of histological type and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage of the detected cervical cancers will be provided.

Data sources and statistical analysis

An overview of data sources and information is seen in table 2.

Table 2.

Overview over data sources and information

| Data sources | Information |

| Danish Pathology Data Bank34 | Participation (yes/no) |

| Participation by self-sampling or GP-based screening | |

| Cervical cytology samples and results in references regions | |

| Results of self-samples, cervical cytology samples and cervical biopsies | |

| Cervical biopsy performed (yes/no) | |

| Conization performed (yes/no) | |

| Screening history | |

| Danish Civil Registration System36 | Residence |

| Date of death, emigration and immigration | |

| Danish National Patient Register38 | Total hysterectomy and cervical amputation procedures Comorbidities |

| Danish Cancer Registry56 | Cervical cancer incidence |

| Statistics Denmark54 | Sociodemographic factors (eg, age, marital status and education level) |

GP, general practitioner.

Baseline characteristics in both groups will be presented using descriptive statistics (numbers and proportions) on screening history, comorbidities, sociodemographic factors (eg, age, marital status and education level). Screening history will be categorised based on the woman’s screening history in a 15-year period before screening exit (ie, age 50–64) according to the results of the cytology screening at age 50–59 and the HPV-exit test at age 60–64. The categorisation of screening history is expected to be as follows6:

(1) ‘Sufficiently screened with normal results’ if women had (a) at least one normal cytology at age 50–54, (b) at least one normal cytology at age 55–59, (c) no abnormal cytology (ASC-US or worse) at age 50–59 and (d) HPV negative at age 60–64; (2) ‘insufficiently screened with normal results’ if women had one or more cytology samples with only normal results, but only in one or two age categories (50–54, 55–59 or 60–64); (3) ‘long-term unscreened’ if no cervical cytology sample at age 50–64; and (4) ‘abnormal screening’ if women (a) had ASC-US or worse at least once at age 50–59 or (b) HPV positive at age 60–64.

Screening participation, cervical cytology samples, numbers of colposcopies/conizations performed, compliance to follow-up among positive self-samplers, and disease outcomes (HPV positivity rate and histological outcomes) will be estimated as proportions. Participation in the intervention group will be reported by age groups, screening history and sampling method (GP vs self-sampling). Regression analyses will be used to estimate the association between CIN2+ detection in women offered cervical cancer screening compared with those not offered screening. Both crude and adjusted estimates will be presented with 95% CIs. Cumulative incidence rates of cervical cancer among women in the intervention and reference groups will be reported, including the distribution of the histological types and FIGO stage of the detected cancers. All statistical analyses will be performed using STATA V.16.

Sample size

The sample size was determined by the primary outcome (CIN2+). In Denmark, approximately 167 000 Danish women are currently aged 65–69 years, 37 000 of whom (22.2%) reside in the CDR (intervention group).22 We anticipate that an estimated 55% of these will not have a record of a cervical cytology sample in the DPDB within the past 5 years. As follows, the study cohort will consist of a total of 91 850 women, including approximately 20 000 women in the intervention group. We assume that 50% of the eligible women in the intervention group will accept the screening offer and that the proportion of CIN2+ is 0.3% among participants. Thus, by including 10 000 women in the intervention group, the study will have a power of 80% to detect a difference in the CIN2+ proportion of 0.1 percentage points between the intervention and reference group. The proportion of CIN2+ that was chosen (0.3%) is a conservative estimate inspired by Swedish data reporting a CIN2+ proportion of 0.38% among 56–60 years old women attending HPV-based screening using the Cobas 4800 test.51

Timeline

The study enrolment is expected to continue until 10 000 participants have been included in the intervention group. Invitations will be sent out prospectively over an expected 4.5-year period starting April 2019.

Patient and public involvement

The research questions were developed in response to the on-going public and scientific discussion in Denmark regarding expanding the upper screening age in the organised cervical cancer screening programme. No patients or patient organisations were involved in the development, design or implementation of this study.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

According to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, the project was listed at the record of processing activities for research projects in the CDR (j. no: 1-16-02-158-18). The study was approved by the Danish Patient Safety Authority (j.no: 3-3013-2634/1). The study protocol has been submitted to the Ethical Committee in the CDR. The Committee decided that according to the Consolidation Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects, Consolidation Act number 1083 of 15 September 2017 section 2 (1), this study is not notifiable to the Committee (j.no.: 73/2018) and informed consent is therefore not required.

Dissemination

The study protocol is made public in this article. The results will be reported through publication of peer-reviewed articles in international scientific journals and presented at national and international scientific meetings. Moreover, the study results will be disseminated to healthcare stakeholders, and patient organisations at scientific meetings, and to the general public through press releases.

Strengths and limitations of this study

To our knowledge, this prospective population-based intervention study will be the first to evaluate if HPV-based cervical cancer screening among older women aged 65–69 years results in an increased detection of CIN2+ cases as compared with women not invited to screening. Importantly, this study will evaluate whether the potential harms of screening in older women are outweighed by the potential benefits of decreasing the incidence of cervical (pre)-cancer.2 52 Overall, this knowledge will address important research gaps and may help guide future screening recommendations. Compared with previous studies which report, by necessity, only the effect of cytology screening at older ages7 23–26 it is of great value for future decision making that this study will be able to determine the effect of screening at older ages in women who have had an exit HPV-test.52

A key strength is that the effect of the screening intervention will be measured prospectively within an organised programme. From an implementation point of view, this will provide reliable estimates of the expected participation rates if extending the upper screening age together with the possibility of self-sampling would become routine. We will identify outcomes from the nationwide DPDB which has highly valid records on all pathology specimens in Denmark,34 and the selection of study participants is population-based and determined by data from the invitation module; thus eliminating both information bias and selection problems. Important limitations should be mentioned. The lack of randomisation gives rise to confounding of both known and unknown risk factors. Age,6 screening history,6 comorbidities,53 education level,6 marital status,6 smoking status7 and sexual behaviour6 may be potential confounding factors for the association between screening status and cervical (pre)-cancer development. Except for smoking status and sexual behaviour, we will be able to assess whether the distribution of the remaining factors is well-balanced between the groups by using individual-level registry data.34 38 54 Ideally, eligible women in all Danish regions should have been individually randomised to the intervention and reference group instead of being allocated to the groups based on their geographical location. Unfortunately, this was not feasible from an organisational point of view. Potentially, there may have been regional differences in the proportion of CIN2+ cases detected prior to the start of our study. If that is the case, it may affect the impact of the intervention on CIN2+ detection rates. Fortunately, we will be able to take into account these potential regional differences by using data from the nationwide DPDB.

Detection of invasive and advanced cervical cancer is the optimal outcome measure to evaluate the effect of screening at older ages,52 but given the relative rarity of cervical cancer in older women, the length of follow-up needed and the large sample size required, we chose CIN2+ and CIN3+ as the primary and secondary outcome, respectively. Yet, it should be noted that the majority of CIN2 and CIN3 lesions detected after age 65 might not have sufficient time to progress to invasive cancer in the remaining lifespan.2 For screening purposes, including CIN2+ and CIN3 cases as the primary and secondary outcomes, respectively, may be justified by them being treatable endpoints (conization) in older non-reproductive women according to Danish guidelines,48 while still recognising that the detection and treatment of CIN3, and especially CIN2, may be considered as overtreatment, because an unknown proportion of these lesions would never have progressed to cancer in the woman’s lifetime.55 Specifically, it is important to take into account that conization is associated with an increased risk of bleeding and stenosis, which may hinder or challenge sampling from the cervix postconization,52 and that false-positive screening results may place some women in a surveillance cycle of unclear end, which may cause distress.55

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Collaborators: Mette Tranberg, Lone Kjeld Petersen, Klara Miriam Elfström, Anne HammerJan Blaakær, Mary Holten Bennetsen, Jørgen Skov Jensen and Berit Andersen.

Contributors: MT is the principal investigator of the study and is responsible for conducting the study overall. BA and MT conceived the original idea. Subsequently, LKP, KME, AH, MHB and JB also contributed to the design of the study. JSJ especially contributed with comments on the laboratory part of the protocol, while LKP, JB and AH have provided clinical advice on follow-up of women with abnormal results. MT is the first author and drafted the first version of this protocol article, which was subsequently further developed by all authors, who also reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding: The initiative and the study was partly funded by the Department of Public Health Programmes, Randers Regional Hospital, which is located in the Central Denmark Region. Some public funding had been provided by the Health Foundation (grant no.:18-B-0125) and other fundraising is on-going. The Health foundation had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in writing the manuscript

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: Roche sponsors the Cobas HPV-DNA test kits and CINtec Plus test kits for the study. According to the contract between Roche and the Department of Public Health Programmes, Randers Regional Hospital, Roche has commented on the protocol article, but had no influence on the scientific process and no editorial rights pertaining to this manuscript. The authors retained the right to submit the manuscript. MT, JB, JSJ and BA have participated in other studies with HPV test kits sponsored by Roche and self-sampling devices sponsored by Axlab. MT has received honoraria from Roche Diagnostics and AstraZeneca for lectures on HPV self-sampling and HPV triage-methods, respectively. AH has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca. All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Second edition-summary document. Ann Oncol 2010;21:448–58. 10.1093/annonc/mdp471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American cancer society, American society for colposcopy and cervical pathology, and American society for clinical pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol 2012;137:516–42. 10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anttila A, von Karsa L, Aasmaa A, et al. Cervical cancer screening policies and coverage in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2649–58. 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rustagi AS, Kamineni A, Weiss NS. Point: cervical cancer screening guidelines should consider observational data on screening efficacy in older women. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:1020–2. 10.1093/aje/kwt167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isidean SD, Franco EL. Counterpoint: cervical cancer screening guidelines-approaching the golden age. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:1023–6. 10.1093/aje/kwt171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Andrae B, Sundström K, et al. Effectiveness of cervical screening after age 60 years according to screening history: nationwide cohort study in Sweden. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002414. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castañón A, Landy R, Cuzick J, et al. Cervical screening at age 50-64 years and the risk of cervical cancer at age 65 years and older: population-based case control study. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001585. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyllensten U, Gustavsson I, Lindell M, et al. Primary high-risk HPV screening for cervical cancer in post-menopausal women. Gynecol Oncol 2012;125:343–5. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, et al. NORDCAN–a Nordic tool for cancer information, planning, quality control and research. Acta Oncol 2010;49:725–36. 10.3109/02841861003782017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman SM, Castanon A, Moss E, et al. Cervical cancer is not just a young woman's disease. BMJ 2015;350:h2729. 10.1136/bmj.h2729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammer A, Kahlert J, Rositch A, et al. The temporal and age-dependent patterns of hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer incidence rates in Denmark: a population-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017;96:150–7. 10.1111/aogs.13057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darlin L, Borgfeldt C, Widén E, et al. Elderly women above screening age diagnosed with cervical cancer have a worse prognosis. Anticancer Res 2014;34:5147–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammer A, Kahlert J, Gravitt PE, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates in Denmark during 2002–2015: a registry-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2019;98:1063–9. 10.1111/aogs.13608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gravitt PE. Evidence and impact of human papillomavirus latency. Open Virol J 2012;6:198–203. 10.2174/1874357901206010198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maglennon GA, Doorbar J. The biology of papillomavirus latency. Open Virol J 2012;6:190–7. 10.2174/1874357901206010190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maglennon GA, McIntosh PB, Doorbar J. Immunosuppression facilitates the reactivation of latent papillomavirus infections. J Virol 2014;88:710–6. 10.1128/JVI.02589-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammer A, de Koning MN, Blaakaer J, et al. Whole tissue cervical mapping of HPV infection: molecular evidence for focal latent HPV infection in humans. Papillomavirus Res 2019;7:82–7. 10.1016/j.pvr.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen B, Christensen BS, Christensen J, et al. HPV-prevalence in elderly women in Denmark. Gynecol Oncol 2019;154:118–23. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.04.680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei J, Ploner A, Lagheden C, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus status and prognosis in invasive cervical cancer: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002666. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynge E, Lönnberg S, Törnberg S. Cervical cancer incidence in elderly women-biology or screening history? Eur J Cancer 2017;74:82–8. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elit L. Role of cervical screening in older women. Maturitas 2014;79:413–20. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Statistics Denmark Statistik databanken 2020, 2020. Available: www.statistikbanken.dk

- 23.Andrae B, Kemetli L, Sparén P, et al. Screening-preventable cervical cancer risks: evidence from a nationwide audit in Sweden. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:622–9. 10.1093/jnci/djn099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenblatt KA, Osterbur EF, Douglas JA. Case-Control study of cervical cancer and gynecologic screening: a SEER-Medicare analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2016;142:395–400. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamineni A, Weinmann S, Shy KK, et al. Efficacy of screening in preventing cervical cancer among older women. Cancer Causes Control 2013;24:1653–60. 10.1007/s10552-013-0239-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rustagi AS, Kamineni A, Weinmann S, et al. Cervical screening and cervical cancer death among older women: a population-based, case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179:1107–14. 10.1093/aje/kwu035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammer A, Soegaard V, Maimburg RD, et al. Cervical cancer screening history prior to a diagnosis of cervical cancer in Danish women aged 60 years and older-a national cohort study. Cancer Med 2019;8:418–27. 10.1002/cam4.1926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson EJ, Maynard BR, Loux T, et al. The acceptability of self-sampled screening for HPV DNA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2017;93:56–61. 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, et al. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ 2018;363:k4823. 10.1136/bmj.k4823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynge E, Clausen LB, Guignard R, et al. What happens when organization of cervical cancer screening is delayed or stopped? J Med Screen 2006;13:41–6. 10.1258/096914106776179773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynge E, Rygaard C, Baillet MV-P, et al. Cervical cancer screening at crossroads. APMIS 2014;122:667–73. 10.1111/apm.12279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danish Health Authority Screening for livmoderhalskræft-anbefalinger 2012 [In English: Cervical cancer screening-recommendations 2012]. Copenhagen [in Danish with English summary], 2012. Available: https://www.sst.dk/~/media/B1211EAFEDFB47C5822E883205F99B79.ashx

- 33.Lynge E, Andersen B, Christensen J, et al. Cervical screening in Denmark - a success followed by stagnation. Acta Oncol 2018;57:354–61. 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1355110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erichsen R, Lash TL, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, et al. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: the Danish national pathology registry and data bank. Clin Epidemiol 2010;2:51–6. 10.2147/CLEP.S9908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjerregaard B, Larsen OB. The Danish pathology register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:72–4. 10.1177/1403494810393563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish civil registration system as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:541–9. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bärnighausen T, Tugwell P, Røttingen J-A, et al. Quasi-experimental study designs series-paper 4: uses and value. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;89:21–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, et al. The Danish national patient registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:449–90. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Danish Agency for Digitisation About NemID, 2020. Available: https://www.nemid.nu/dk-en/about_nemid/

- 40.Pedersen KM, Andersen JS, Søndergaard J. General practice and primary health care in Denmark. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25 Suppl 1:S34–8. 10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Baars R, Bosgraaf RP, ter Harmsel BWA, et al. Dry storage and transport of a cervicovaginal self-sample by use of the evalyn brush, providing reliable human papillomavirus detection combined with comfort for women. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:3937–43. 10.1128/JCM.01506-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tranberg M, Bech BH, Blaakær J, et al. Study protocol of the choice trial: a three-armed, randomized, controlled trial of home-based HPV self-sampling for non-participants in an organized cervical cancer screening program. BMC Cancer 2016;16:835. 10.1186/s12885-016-2859-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tranberg M, Bech BH, Blaakær J, et al. Preventing cervical cancer using HPV self-sampling: direct mailing of test-kits increases screening participation more than timely opt-in procedures - a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2018;18:273. 10.1186/s12885-018-4165-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tranberg M, Jensen JS, Bech BH, et al. Good concordance of HPV detection between cervico-vaginal self-samples and general practitioner-collected samples using the COBAS 4800 HPV DNA test. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:348. 10.1186/s12879-018-3254-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heideman DAM, Hesselink AT, Berkhof J, et al. Clinical validation of the COBAS 4800 HPV test for cervical screening purposes. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:3983–5. 10.1128/JCM.05552-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao A, Young S, Erlich H, et al. Development and characterization of the COBAS human papillomavirus test. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:1478–84. 10.1128/JCM.03386-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ejegod DM, Hansen M, Christiansen IK, et al. Clinical validation of the COBAS 4800 HPV assay using cervical samples in SurePath medium under the VALGENT4 framework. J Clin Virol 2020;128:104336. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petersen LK. National clinical guideline for cervical dysplasia. Examination, treatment, and management of women aged 60 and older [Only in Danish]: DSOG, 2019. Available: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Opgaver/Patientforl%C3%B8b-og-kvalitet/NKR/Puljefinansierede-NKR/pdf-version-af-published_guideline_2633.ashx?la=da&hash=0809DD9A773B341B3D08AE73C9361E2AB84029E8

- 49.Petersen LK. Examination, treatment and control of cervical dysplasia [Only in Danish]: 2013: DSOG, 2013. Available: http://gynobsguideline.dk/hindsgavl/Cervixdysplasi2012.pdf

- 50.Gustafson LW HA, Petersen LK, Andersen B. “See and Treat” in an outpatient setting in women above 45 years with cervical dysplasia. For study protocol. See Clinicaltrials.gov. NCT:04298957, 2020

- 51.Sahlgren H, Elfström KM, Lamin H, et al. Colposcopic and histopathologic evaluation of women with HPV persistence exiting an organized screening program. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;222:253.e1–253.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gravitt PE, Landy R, Schiffman M. How confident can we be in the current guidelines for exiting cervical screening? Prev Med 2018;114:188–92. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diaz A, Kang J, Moore SP, et al. Association between comorbidity and participation in breast and cervical cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol 2017;47:7–19. 10.1016/j.canep.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, et al. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:12–16. 10.1177/1403494811399956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawaya GF. Cervical cancer screening in women over 65. Con: reasons for uncertainty. Gynecol Oncol 2016;142:383–4. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.08.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gjerstorff ML. The Danish cancer registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:42–5. 10.1177/1403494810393562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.