Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to compare the clinical outcomes and operative cost of a locked compression plate (LCP) and a nonlocked reconstruction plate in the treatment of displaced midshaft clavicle fracture.

Methods

From January 2013 till March 2018, a total of 55 patients with acute unilateral closed midshaft clavicle fracture were treated with either a 3.5-mm pre-contoured LCP [32 patients; 25 men and 7 women; mean age: 35 years (range: 19–63 years)] or a 3.5-mm nonlocked reconstruction plate [23 patients; 20 men and 3 women; mean age: 31.4 years (range: 17–61 years)]. The clinical outcomes in terms of fracture union, Quick Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score, implant irritation, failure rate, and reoperation rate were evaluated retrospectively. The patient billing records were reviewed to obtain primary operation, reoperation, and total operative cost for midshaft clavicle fracture. These values were analyzed and converted from Malaysia Ringgit (RM) to United States Dollar (USD) at the exchange rate of RM 1 to USD 0.24. All patients were followed up for at least one-year duration.

Results

The mean time to fracture union, implant irritation, implant failure, and reoperation rate showed no significant difference between the two groups of patients. The mean Quick DASH score was significantly better in the reconstruction plate group with 13 points compared with 28 points in the LCP group (p=0.003). In terms of total operative cost, the LCP group recorded a cost of USD 391 higher than the reconstruction plate group (p<0.001).

Conclusion

The 3.5-mm reconstruction plate achieved not only satisfactory clinical outcomes but was also more cost-effective than the LCP in the treatment of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures.

Level of Evidence

Level III, Therapeutic study

Keywords: Midshaft, Clavicle, Fracture, Locking compression plate, Reconstruction plate

Introduction

Clavicle fractures are relatively common accounting for 2.6–4.6% of all adult fractures (1). Midshaft clavicular fractures have been traditionally treated with conservative management regardless of the degree of displacement because most of the early reports showed that nonunion in this type of fracture was quite rare (2).

However, this management concept had evolved from conservative to operative since last decade. A multicenter randomized controlled trial had shown that displaced midshaft clavicular fractures treated operatively with plate fixation were superior in terms of fracture union and functional outcomes as compared with conservative management (3). Moreover, operative management of midshaft clavicular fracture had resulted in an earlier return to work and a better functional outcome (4, 5).

The methods of operative fixation for midshaft clavicle fracture are mainly open reduction and internal fixation with wires, pins, or plates with screws (6–8). The unique anatomical shape of clavicle poses a challenge for the surgeon during reduction and implant placement. Hence, the pre-contoured locked plate is now the preferred choice of implant for this type of clavicle fractures because it provides greater stability and ease for plate placement (9). However, being a non–weight bearing bone, the question of fixation with a mechanical superior 3.5-mm locked compression plate (LCP) was raised.

This study was carried out with the objective of comparing the clinical outcome of displaced clavicle fracture fixed with the LCP and the nonlocked reconstruction plate. In addition, the operative cost between the two groups was compared to look for a more cost-effective type of plate for displaced midshaft clavicle fracture.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (MRECID No: 2017116-5800). Between January 2013 and June 2018, a total of 72 cases of midshaft clavicle plating were performed in our hospital by orthopedic surgeon and senior registrar. Of them, 55 patients, who met inclusion criteria and could be followed up at least once a year, were reviewed retrospectively. A total of 32 cases of displaced midshaft clavicle fracture were treated with the LCP (3.5-mm pre-contoured superior-anterior clavicle plate, Depuy Synthes, Monument, CO, USA) and remaining 23 cases were treated with the nonlocked reconstruction plate placed in superior position (3.5-mm straight plate, OSA Technology, Selangor, Malaysia). Indication of operative management includes closed fracture with displacement or shortening of more than 20 mm. Exclusion criteria include patients with associated fracture on ipsilateral upper limb that might affect the Quick Disability Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score, nonunion, malunited midshaft clavicle fractures, open midshaft clavicle fracture, and associated neurovascular injury. One case of grade 1 open fracture treated with debridement and fixation with the LCP in a single-stage procedure was excluded because it might affect the fracture union time, the functional score, and the implant failure rate.

The details on fracture fixation, including plate length, plate screw density (PSD), number of cortices fixed on each side of fracture, and fixation technique, were obtained from operation notes and postoperative radiograph. In this study, simple fractures were treated with the compression technique, whereas comminuted fractures were treated with either the lag screw with neutralization technique or the bridging technique. All fractures in the reconstruction plate group were fixed with three cortex screws with bicortical purchased on each side of the fracture. In the LCP group, there were six cases of fracture fixed with two locked head screws with bicortical purchased on each side of the fracture. The average length of the reconstruction plate used was 97.1 mm, and the average length of the LCP was 102.6 mm. The average PSDs for reconstruction plate and LCP groups were 0.76 and 0.79, respectively.

In the LCP group, the mean follow-up period was 13.9 months (range: 12–26 months). There were 25 males and 7 females with a mean age of 35.0 years (range: 19–63 years). The mechanism of injury was motor vehicle accident in 28 cases, fall in 3 cases, and contact sport injury in 1 case. Four cases associated with rib fracture and one case associated with ipsilateral midshaft femur fracture were included in this study. According to Robinson’s classification, there were 28 cases of type 2 B1 (simple or wedge comminuted) and 4 cases of type 2 B2 (isolated or comminuted segmental) displaced midshaft clavicle fractures treated with the LCP.

In the reconstruction plate group, the mean follow-up time was 14.3 months (range: 12–22 months). There were 20 males and 3 females with a mean age of 31.4 years (range: 17–61 years). The mechanism of injury was motor vehicle accident except one case of contact sport injury. There were two cases associated with ipsilateral femur shaft fracture. There were 16 cases of Robinson 2 B1 type and 7 cases of 2 B2 type displaced midshaft clavicle fractures encountered. All the fractures were operated within 2 weeks of injury.

The earliest plain X-ray radiograph with complete bridging callous across fracture site was used as evidence of fracture union. Implant failure was defined as any change in position or shape of the implant visualized on serial radiograph. Implant irritation was defined as persistent pain or discomfort owing to prominent implant despite fracture united. For functional assessment, the Quick DASH scores were evaluated through patient interview.

The operative billing records were reviewed to identify the primary operative cost for clavicle fixation and the reoperation cost. The cost of implant used was included in the primary operative cost. Excluded costs were inpatient fees, pharmacy services, and laboratory and imaging fees. These costs were nonoperative and subjected to various confounding factors. Summation of primary operation and reoperation costs was recorded as the total operation cost. All these costs were reported in United States Dollar (USD).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 22.0 (IBM SPSS Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA). The data were analyzed with an independent t-test and a Chi-square test. A p-value of <0.05 was the measure of significant difference.

Results

Demographic

In this study, the patient’s demographic data, including age, gender, mechanism of injury, and fracture pattern, showed no intergroup significant differences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients

| Parameter | Reconstruction plate n=23 | LCP n=32 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year)a | 31.4 (range: 17–61) | 35.0 (range: 19–63) | 0.323 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 20 | 25 | 0.434 |

| Female | 3 | 7 | |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 15 | 22 | 0.992 |

| No | 8 | 10 | |

| Mechanism of injury | |||

| Motor vehicle accident | 22 | 28 | 0.315 |

| Falls | 0 | 3 | |

| Sports injury | 1 | 1 | |

| Fracture pattern (Robinson classification type 2) | |||

| B1 | 16 | 28 | 0.852 |

| B2 | 7 | 4 |

LCP: locked compression plate amedian (interquartile range)

Data on fracture fixation showed no intergroup significant difference with regard to the fixation technique, the plate length, and the PSD. However, there are a significantly lower number of cortices fixed on each side of the fracture using locked head screw as than cortex screw (Table 2).

Table 2.

Details of fracture fixation

| Fracture fixation | Reconstruction plate n=23 | LCP n=32 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | |||

| Compression | 12 | 21 | 0.452 |

| Neutralization | 7 | 6 | |

| Bridging | 4 | 5 | |

| Number of bicortical fixation each side fracture | |||

| Two | 0 | 6 | 0.035 |

| Three | 23 | 26 | |

| Plate length (mm)a | 97.1 (13.6) | 102.6 (9.1) | 0.078 |

| PSD | 0.76 (range: 0.60–0.86) | 0.79 (range: 0.67–1.00) | 0.177 |

LCP: locked compression plate; PSD: plate screw density

Mean (standard deviation)

Bone union and functional outcome assessment

Fracture union was achieved in all the cases from both groups (Figure 1). The average fracture union time was 15.17±6.27 weeks in the reconstruction plate group as compared with 13.16±3.92 weeks in the LCP group, showing no significant intergroup differences (p>0.05). In terms of functional assessment with Quick DASH, the reconstruction plate group achieved a significantly lower mean score of 15.29 than that for the LCP group (p<0.05). The mean score for the reconstruction plate group was 13.04±16.63 in comparison with the mean score of 28.33±18.76 for LCP group (Table 3).

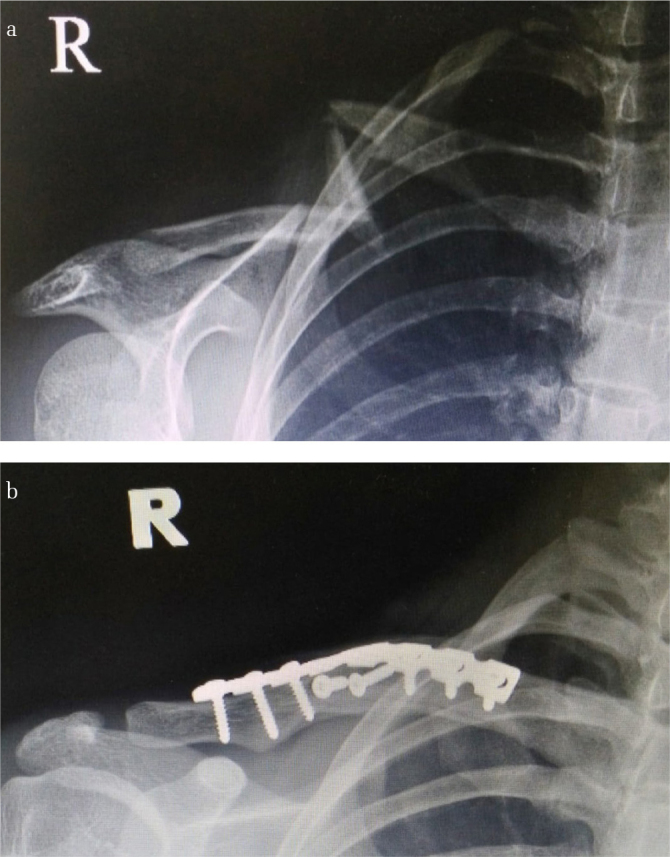

Figure 1. a, b.

21-year-old girl sustained closed displaced fracture of right midshaft clavicle treated with open reduction internal fixation using 3.5-mm reconstruction plate and interfragmentary lag screws. (a) Pre-operative radiograph showed Robinson type 2 B2 fracture with skin tented by sharp medial fracture fragment. (b) Radiograph at 30 weeks postoperatively showed that fracture union, screw, and plate remain intact

Table 3.

Results of clinical outcomes

| Outcome | Reconstruction plate n (%) N=23 | LCP n (%) N=32 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture union period (week)a | 15.17 (6.27) | 13.16 (3.92) | 0.148 |

| Quick DASH scorea | 13.04 (16.63) | 28.33 (18.76) | 0.003 |

| Implant irritation | 2 (3.6) | 10 (18.2) | 0.055 |

| Implant failure | |||

| Screw loosening | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0.418 |

| Plate breakage | — | — | — |

| Reoperation Indications | |||

| Symptomatic implant | 2 (3.6) | 6 (10.9) | 0.720 |

| Refracture | 1 (1.8) | — | |

| NA | |||

LCP: locked compression plate; NA: not applicable.

Mean (standard deviation)

Postoperative complications

The overall implant irritation rate of midshaft clavicle plating was 21.8% in this study. The implant irritation rates for reconstruction plate and LCP groups were 3.6% and 18.2%, respectively. However, statistical result showed no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the implant irritation rate (p>0.05). In this study, one case of implant failure with screws loosened was found in the reconstruction plate group (Figure 2). The overall reoperation rate was 16.3% in this study with recorded rates of 5.4% and 10.9% in reconstruction plate and LCP groups, respectively. Indication for reoperation in this study was implant irritation, which persisted despite fracture united, and the symptom was not tolerable by patients (Figure 3). In addition, there was a case of refracture and undergoing reoperation in this study. This case was from the reconstruction plate group following another motor vehicle accident after fracture united. There was no significant difference between the two groups of patients in terms of the reoperation rate (p>0.05) (Table 3).

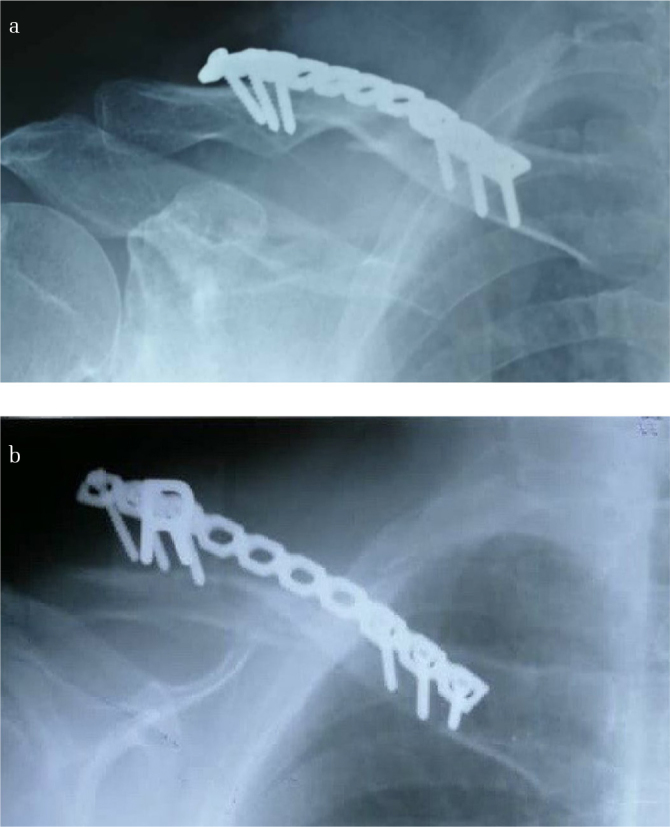

Figure 2. a, b.

63-year-old man with Robinson type 2 B2 clavicle fracture treated with 3.5-mm reconstruction plate. (a) Immediate postoperative radiograph with acceptable reduction. (b) Radiograph at 5 months shows lateral screws loosened with soft tissue irritation. Removal implant done and fracture union noted intraoperatively

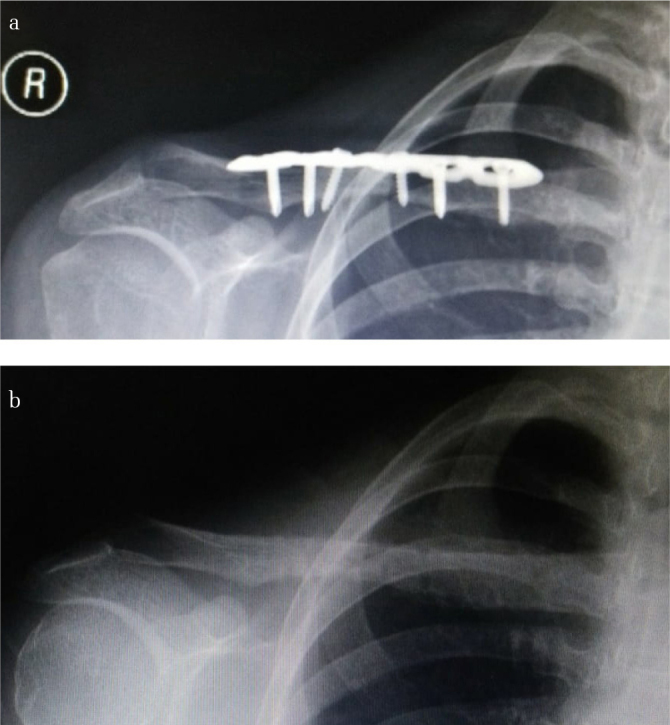

Figure 3. a, b.

32-year-old lady with Robinson type 2 B1 clavicle fracture underwent fixation with 3.5-mm locking compression plate. (a) Radiograph at 16 weeks showed fracture union. However, patient complained persistent pain because of prominent implant. (b) Radiograph of united clavicle after implant removed 10 months postoperatively, with pain resolved during follow-up

Operative costs

In terms of operative cost, the average primary operative cost for the fixation of midshaft clavicle using a reconstruction plate was USD 956 in comparison with the cost of using LCP, which was USD 1,338. The difference was USD 382 with fixation using the reconstruction plate costing less than the LCP (p<0.001). The average reoperation costs for reconstruction plate and LCP groups were USD 221 and USD 200, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of reoperation cost (p>0.05). The average total operative costs, regardless of whether the implants were removed in reconstruction plate and LCP groups, were USD 985 and USD 1,376, respectively. The cost difference was USD 391 with the average total cost of fixation using a reconstruction plate being less than that of LCP fixation (p<0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Operative cost comparisona

| Cost (USD) | Reconstruction plate mean (SD) | LCP mean (SD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary operative | 956 (146) | 1,338 (258) | <0.001 |

| Reoperation | 221 (63) | 200 (50) | 0.600 |

| Total operative | 985 (181) | 1,376 (264) | <0.001 |

LCP: locked compression plate; SD: standard deviation.

Value rounded to nearest whole United States Dollar

Discussion

The management of displaced midshaft clavicle fracture remains a debatable topic among clinicians with some in favor of conservative management. However, recent studies had shown a better clinical outcome, including earlier return to work in patient treated surgically. Various comparison studies had been done on different plates used in midshaft clavicle fracture fixation (10–12). With regard to this report, the authors found no literature on the clinical outcome and operative cost comparison between the 3.5-mm reconstruction plate and the 3.5-mm LCP in displaced midshaft clavicle fracture.

In our study, overall, the fractures united within an expected period, and the result was comparable with earlier study (11). There was no case of fracture malunion or nonunion noted between the two groups of patients during the follow-up period. This result implies that reduced midshaft clavicle fracture had good potential for union. This study found that the reconstruction plate group had significantly better Quick DASH score as compared with the LCP counterpart. This result further supports the report by Cho et al. on comparison between locked and nonlocked reconstruction plates, which showed no significant difference in the Quick DASH score (11).

The reconstruction plate failure rate reported from our study was 1.8%. This is lower than 8.0–12.6% described in several other clinical studies (13, 14). In addition, there was no significant difference in terms of the implant failure rate between the two types of implant used in midshaft clavicle fracture fixation within our study population. The work of Gilde et al. showed higher implant failure rate with the 2.7-mm nonlocked reconstruction plate in midshaft clavicle fracture fixation (14). The difference in the clavicle diameter size between Caucasian and Asian could be an important factor for the failure of a thinner 2.7-mm reconstruction plate. However, there was no single interpopulation study comparing the failure rate of nonlocked reconstruction plates in this literature. One out of 23 cases of the reconstruction plate group that had failure with loosened medial screw was noted in an elderly man aged 63 years. Although screw loosened, the reconstruction plate remained intact and fracture united. The patient underwent removal operation because of discomfort from prominent screw. Owing to lower pull-out strength, cortical screw loosening is a possible risk when it is used in elderly patient with porotic bone quality, as described by Meeuwis et al. (13).

Biomechanical study by Rowling et al. showed no significant torque and bending response between bicortical locked and nonlocked screw construct (15). In our study, all fractures were fixed with bicortical screws and showed no significant difference in the implant failure rate. In contrast, the use of unicortical locked screw construct become more favorable owing to lower neurovascular risk. This is supported by biomechanical studies that showed similar bending stiffness among locked bicortical, unicortical, unicortical far cortex abutting, and hybrid unicortical construct (15–17).

The reoperation rate in the LCP following hardware irritation was reported in the literature and ranged between 13% and 30% (18, 19). This is similar to our report on the irritation rate of 18.2%, with a removal rate of 10.9% in the LCP group. The pre-contoured LCP is mainly designed based on the Caucasian population. Thus, using this type of LCP is potentially giving a high risk of implant irritation in Asian population (20).

Regarding operative cost, treating displaced midshaft clavicle fracture using a 3.5-mm LCP was significantly more expensive than using a 3.5-mm nonlocked reconstruction plate. This difference was mainly contributed by the difference in implant cost, with 3.5-mm LCP costing about 5.7 times more than 3.5-mm nonlocked reconstruction plate in our institution (USD 96 versus USD 552). In addition, reoperation owing to symptomatic implant irritation has contributed to higher overall medical expenditure to the patient. Despite higher expenses, no statistically significant difference was found in the fracture union rate and the implant failure rate between the 3.5-mm nonlocked reconstruction plate group and the LCP group. This study provides an objective reference for the cost-effectiveness between the two types of plate in treatment of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures.

There are few limitations in this study. This is a retrospective study with a small number of cases. Selection bias after excluding patients defaulted from follow-up and incomplete data were unavoidable. Therefore, a prospective study with large population should be performed in future to ascertain the clinical effectiveness of these implants. In addition, the data of operative costs were collected retrospectively over the 5-year period. Over time, there were likely changes in operation fee and implant price because of inflation and government tax on medical implant.

In conclusion, superior midshaft clavicular fracture fixation with a 3.5-mm nonlocked reconstruction plate was not only cost-effective but also resulted in better functional score. Given higher rate of soft tissue irritation with the LCP, this formed an important part of information during pre-operative patient counseling.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Midshaft clavicular plating commonly complicated with symptomatic implant irritation post-operatively.

Nonlocked reconstruction plate is as effective as locked compression plate in midshaft clavicular fracture fixation.

Nonlocked reconstruction plate group showed significant better functional score.

Nonlocked reconstruction plate is more cost effective than locked compression plate in midshaft clavicular fracture.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the Medical Research Ethics Committee University of Malaya Medical Center (MRECID No: 2017116-5800).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all study patients.

Author Contributions: Concept - J.T.G.; Design - J.T.G.; Supervision - S.K.C.; Materials - J.T.G., T.B.T.J.; Data Collection and/or Processing - J.T.G., T.B.T.J.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - J.T.G., T.B.T.J.; Literature Search - J.T.G., S.K.C.; Writing Manuscript - J.T.G.; Critical Review - J.T.G., S.K.C.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Stegeman SA, de Jong M, Sier CF, et al. Displaced midshaft fractures of the clavicle: non-operative treatment versus plate fixation (Sleutel-TRIAL). A multicenter randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neer CS. Nonunion of the clavicle. J Am Med Assoc. 1960;172:1006–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020100014003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society. Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fracture. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1–10. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Althausen PL, Shannon S, Lu M, et al. Clinical and financial comparison of operative and nonoperative treatment of displaced clavicle fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:608–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Olden GD. VA-LCP anterior clavicle plate: The anatomical precontoured fixation system with angular stability for clavicle shaft fracture. Musculoskelet Surg. 2014;98:217–23. doi: 10.1007/s12306-013-0302-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu CM, Wang SJ, Lin LC. Fixation of mid-third clavicular fractures with Knowles pin: 78 patients followed for 2–7 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:134–9. doi: 10.1080/000164702753671696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuang TY, Ho WP, Hsieh PH, Lee PC, Chen CH, Chen YJ. Closed reduction and internal fixation of acute midshaft clavicular fractures using cannulated screws. J Trauma. 2006;60:1315–20. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195991.80809.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YS, Lin CC, Huang CR, Chen CN, Liao WY. Operative treatment of midclavicular fractures in 62 elderly patients: Knowles pin versus plate. Orthopaedics. 2007;30:959–64. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20071101-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VanBeek C, Boselli KJ, Cadet ER, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Precountered plating of clavicle fractures. Decreased hardware related complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:3337–43. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wijdicks FJG, Van der Meijden OA, Millett PJ, Verleisdonk EJMM, Houwert RM. Systemic review of the complications of plate fixation of clavicle fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:617–25. doi: 10.1007/s00402-011-1456-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho CH, Song KS, Min BW, Bae KC, Lee KJ. Operative treatment of clavicle midshaft fractures: Comparison between reconstruction plate and reconstruction locking compression plate. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2:154–9. doi: 10.4055/cios.2010.2.3.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai YC, Tarng YW, Hsu CJ, Chang WN, Yang SW, Renn JH. Comparison of dynamic and locked plates for treating midshaft clavicle fractures. Orthopaedics. 2012;35:697–702. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120426-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meeuwis MA, Pull Ter Gunne AF, Verhofstad MHJ, van der Heijden FHWM. Construct failure after open reduction and plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. Injury. 2017;48:715–9. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilde AK, Jones CB, Sietsema DL, Hoffmann MF. Does plate type influence the clinical outcomes and implant removal rate in midclavicular fractures fixed with 2.7-mm anteroinferior plates? A retrospective cohort study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:55. doi: 10.1186/s13018-014-0055-x. doi: 10.1186/s13018-014-0055-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rawlings M, Knox D, Patel M, Ackland D. A hybrid approach to mid-shaft clavicle fixation. Injury. 2016;47:893–8. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croley JS, Morris RP, Amin A, Lindsey RW, Gugala Z. Biomechanical comparison of bicortical, unicortical and unicortical far-cortex-abutting screw fixations in plated comminuted midshaft clavicle fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41:703–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Looft JM, Corrêa L, Patel M, Rawlings M, Ackland DC. Unicortical and bicortical plating in the fixation of comminuted fractures of the clavicle: A biomechanical study. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:915–20. doi: 10.1111/ans.14139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saidapur SK, Khadabadi NA. Locking plate fixation of mid-shaft clavicle fracture: Analysis of complications, reoperation rates and functional outcome. Int J Orthop Sci. 2017;3:1071–3. doi: 10.22271/ortho.2017.v3.i3o.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fridberg M, Ban I, Issa Z, Krasheninnikoff M, Troelsen A. Locking plate osteosynthesis of clavicle fractures: complication and reoperation rates in one hundred and five consecutive cases. Int Orthop. 2013;37:689–92. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1793-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu XS, Wang XB, Zhang Y, Zhu YC, Guo X, Chen YX. Anatomical study of the clavicles in a Chinese population. Biomed Res Int. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/6219761. doi: 10.1155/2016/6219761. Epub 2016 Mar 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]