Abstract

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19), which is most frequently mild yet can be severe and life-threatening. Virus-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies are predicted to reduce viral load, ameliorate symptoms, and prevent hospitalization.

Methods

In this ongoing phase 2 trial involving outpatients with recently diagnosed mild or moderate Covid-19, we randomly assigned 452 patients to receive a single intravenous infusion of neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in one of three doses (700 mg, 2800 mg, or 7000 mg) or placebo and evaluated the quantitative virologic end points and clinical outcomes. The primary outcome was the change from baseline in the viral load at day 11. The results of a preplanned interim analysis as of September 5, 2020, are reported here.

Results

At the time of the interim analysis, the observed mean decrease from baseline in the log viral load for the entire population was −3.81, for an elimination of more than 99.97% of viral RNA. For patients who received the 2800-mg dose of LY-CoV555, the difference from placebo in the decrease from baseline was −0.53 (95% confidence interval [CI], −0.98 to −0.08; P=0.02), for a viral load that was lower by a factor of 3.4. Smaller differences from placebo in the change from baseline were observed among the patients who received the 700-mg dose (−0.20; 95% CI, −0.66 to 0.25; P=0.38) or the 7000-mg dose (0.09; 95% CI, −0.37 to 0.55; P=0.70). On days 2 to 6, the patients who received LY-CoV555 had a slightly lower severity of symptoms than those who received placebo. The percentage of patients who had a Covid-19–related hospitalization or visit to an emergency department was 1.6% in the LY-CoV555 group and 6.3% in the placebo group.

Conclusions

In this interim analysis of a phase 2 trial, one of three doses of neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 appeared to accelerate the natural decline in viral load over time, whereas the other doses had not by day 11. (Funded by Eli Lilly; BLAZE-1 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04427501.)

Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) emerged in late 2019 and spread rapidly, resulting in a global pandemic. Infected persons can have a wide range of disease severity, with many patients showing mild or even asymptomatic disease. However, for unknown reasons, up to 10% of asymptomatic and mild infections lead to more severe outcomes, including respiratory distress requiring hospitalization.1 Although risk factors for more severe outcomes have been described (including an older age, obesity, hypertension, and underlying chronic medical conditions),2,3 the connection between viral load and outcomes has not previously been tested in a longitudinal study. Several treatment options have been explored for hospitalized patients with Covid-19 (e.g., antimalarial drugs,4 antiviral agents,5-7 immunomodulators,8-12 glucocorticoids,13,14 and convalescent plasma15,16) with varying results. However, there have been no large randomized, controlled trials of targeted treatments that are specific for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and that are intended to attenuate disease progression in patients with early disease.

Preclinical studies of neutralizing-antibody treatments for SARS-CoV-2 infection in several animal models have shown promising results, with marked reductions in viral loads in the upper and lower respiratory tracts.17 SARS-CoV-2 gains entry into cells through binding of its spike protein to receptors for angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 on target cells.18 LY-CoV555 (also known as LY3819253), a potent antispike neutralizing monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity to the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2, was derived from convalescent plasma obtained from a patient with Covid-19. The antibody was developed by Eli Lilly after its discovery by researchers at AbCellera and at the Vaccine Research Center of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The discovery of LY-CoV555 and its passive protection against SARS-CoV-2 in nonhuman primates has been reported previously.19

Here, we report interim results from the Blocking Viral Attachment and Cell Entry with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies (BLAZE-1) trial, an ongoing phase 2 trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of LY-CoV555 in patients with recently diagnosed mild or moderate Covid-19 in the outpatient setting. We examined the effect of the neutralizing antibody on viral load, symptom scores, and clinical outcomes and also report an observed connection between a persistently high viral load and disease severity.

Methods

Trial Design, Treatment, and Oversight

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-dose trial conducted at 41 centers in the United States, all the patients had positive results on testing for SARS-CoV-2 and presented with one or more mild or moderate symptoms. The investigators reviewed the symptoms, risk factors, and other inclusion and exclusion criteria before enrollment. (A full list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in the protocol, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.) Each patient received a single intravenous infusion of LY-CoV555 or placebo monotherapy over approximately 1 hour. Although the trial contains additional treatment groups, here we focus on the interim analysis of results from only four of these groups: LY-CoV555 at doses of 700 mg, 2800 mg, and 7000 mg and placebo. (Clinical details are also provided in the protocol.)

The preplanned interim analysis was triggered on September 5, 2020, when the last patient who was randomly assigned to receive LY-CoV555 reached day 11. The analysis includes all the data regarding virologic features and symptoms that were available at the time of the database lock. The doses of LY-CoV555 that were evaluated in this trial were based on pharmacologic modeling that predicted that the 700-mg dose would be efficacious. (Details about dose selection are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.) Given the gravity of the pandemic, the doses that were administered in this trial were increased by up to a factor of 10 over the predicted efficacious dose to ensure adequate target coverage. The use of these doses was supported by safety data from a phase 1 trial of LY-CoV555 involving hospitalized patients. Dose levels were fixed, and either LY-CoV555 or placebo was administered within 3 days after positive results on SARS-CoV-2 testing.

The trial, which was sponsored by Eli Lilly, was conducted in accordance with principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical guidelines of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. All the patients provided written informed consent.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change from baseline in the SARS-CoV-2 viral load at day 11 (±4 days) after positive results on testing. Data regarding virologic features and symptoms were collected up to day 29 in this trial. The viral load was measured by means of a nasopharyngeal swab, which was followed by quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) assay at a central laboratory. (Details regarding testing are provided in the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix.) Key secondary outcomes were safety assessments, symptom burden as reported by the patient on a questionnaire, and clinical outcomes. The major clinical outcome was defined as Covid-19–related in-patient hospitalization, a visit to the emergency department, or death. No deaths were reported, and since most emergency department visits resulted in hospital admissions, we refer to a composite of emergency department visits and in-patient hospitalizations simply as hospitalizations. This report includes an analysis of the primary outcome as well as safety and adverse-event data, information regarding symptoms, and clinical outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the sample size, we used a dynamic model to simulate viral load over time in patients treated with LY-CoV555 or placebo. This simulated population was used to estimate the statistical power and comparisons in the change from baseline in viral load. (Details are provided in Section 5.2 in the statistical analysis plan, which is included in the protocol document.) All the patients who had undergone randomization and who had received either LY-CoV555 or placebo were included in the primary analysis if their viral-load measures were available both at baseline and at least once after baseline.

Treatment effects were compared with the use of two-sided tests with an alpha level of 0.05. Adjustments for multiple testing were not performed. Significance testing for the primary outcome was performed with the use of a repeated-measures analysis as a mixed model. (Details regarding these methods are provided in Section 6.10 in the statistical analysis plan.)

Results

Patients

From June 17 through August 21, 2020, a total of 467 patients underwent randomization to receive either LY-CoV555 (317 patients) or placebo (150 patients), and the patients in the LY-CoV555 group were assigned to one of three dose subgroups. Of the patients who had undergone randomization, 452 met the criteria for inclusion in the primary analysis (309 in the LY-CoV555 group and 143 in the placebo group). LY-CoV555 was administered to these patients in doses of 700 mg (101 patients), 2800 mg (107 patients), or 7000 mg (101 patients) (Figure 1). The two trial groups were well balanced regarding risk factors at the time of enrollment (Table 1). Nearly 70% of the patients had at least one risk factor — an age of 65 years or older, a body-mass index (BMI, the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) of 35 or more, or at least one relevant coexisting illness — for severe Covid-19. After undergoing randomization, patients received an infusion of LY-CoV555 or placebo within a median of 4 days after the onset of symptoms; at the time of randomization, more than 80% of the patients had only mild symptoms. The observed mean PCR cycle threshold (Ct) value of 23.9 on the day of infusion (equating to approximately 2.5 million RNA equivalents) matched expectations that a recently diagnosed population would have a high viral burden. The conversion from Ct value to viral load is described in Section 6.10 of the statistical analysis plan.

Figure 1. Enrollment and Trial Design.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.*.

| Characteristic | LY-CoV555 (N=309) |

Placebo (N=143) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Median (range) — yr | 45 (18–86) | 46 (18–77) |

| 65 Yr or older — no. (%) | 33 (10.7) | 20 (14.0) |

| Female sex — no. (%) | 171 (55.3) | 78 (54.5) |

| Race or ethnic group — no./total no. (%)† | ||

| White | 269/305 (88.2) | 120/138 (87.0) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 135/309 (43.7) | 63/143 (44.1) |

| Black | 22/305 (7.2) | 7/138 (5.1) |

| Body-mass index‡ | ||

| Median | 29.4 | 29.1 |

| ≥30 to <40 — no./total no. (%) | 112/304 (36.8) | 56/139 (40.3) |

| ≥40 — no./total no. (%) | 24/304 (7.9) | 9/139 (6.5) |

| Risk factors for severe Covid-19 — no. (%)§ | 215 (69.6) | 95 (66.4) |

| Disease status — no. (%) | ||

| Mild | 232 (75.1) | 113 (79.0) |

| Moderate | 77 (24.9) | 30 (21.0) |

| Median no. of days since onset of symptoms | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Mean viral load — Ct value¶ | 23.9 | 23.8 |

Covid-19 denotes coronavirus disease 2019.

Race or ethnic group was reported by the patients, who could choose more than one category.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Risk factors were an age of 65 years or older, a body-mass index of 35 or more, or at least one coexisting illness in certain prespecified categories.

Ct denotes the cycle threshold of the reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay.

Primary Outcome

By day 11, the majority of patients had a substantial trend toward viral clearance, including those in the placebo group. The observed mean decrease from baseline in the log viral load for the entire population was −3.81 (baseline mean, 6.36; day 11 mean, 2.56); this value corresponded to a decrease by more than a factor of 4300 in the SARS-CoV-2 burden, for an elimination of more than 99.97% of viral RNA. For patients who received the 2800-mg dose of LY-CoV555, the difference from placebo in the decrease from baseline was −0.53 (95% confidence interval [CI], −0.98 to −0.08; P=0.02), for a lower viral load by a factor of 3.4 (Table 2). However, smaller differences from placebo in the decrease from baseline were observed among the patients who received the 700-mg dose (−0.20; 95% CI, −0.66 to 0.25; P=0.38) and the 7000-mg dose (0.09; 95% CI, −0.37 to 0.55; P=0.70).

Table 2. Change from Baseline in Viral Load.

| Variable | LY-CoV555 (N=309) |

Placebo (N=143) |

Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Mean change from baseline in viral load at day 11 | −3.47 | ||

| 700 mg, −3.67 | −0.20 (−0.66 to 0.25) | ||

| 2800 mg, −4.00 | −0.53 (−0.98 to −0.08) | ||

| 7000 mg, −3.38 | 0.09 (−0.37 to 0.55) | ||

| Pooled doses, −3.70 | −0.22 (−0.60 to 0.15) | ||

| Secondary outcomes * | |||

| Mean change from baseline in viral load at day 3 | −0.85 | ||

| 700 mg, −1.27 | −0.42 (−0.89 to 0.06) | ||

| 2800 mg, −1.50 | −0.64 (−1.11 to −0.17) | ||

| 7000 mg, −1.27 | −0.42 (−0.90 to 0.06) | ||

| Pooled doses, −1.35 | −0.49 (−0.87 to −0.11) | ||

| Mean change from baseline in viral load at day 7 | −2.56 | ||

| 700 mg, −2.82 | −0.25 (−0.73 to 0.23) | ||

| 2800 mg, −3.01 | −0.45 (−0.92 to 0.03) | ||

| 7000 mg, −2.85 | −0.28 (−0.77 to 0.20) | ||

| Pooled doses, −2.90 | −0.33 (−0.72 to 0.06) |

Data regarding hospitalization, another key secondary outcome, are provided in Table 3.

Secondary Viral Outcomes

On day 3, among the patients who received the 2800-mg dose of LY-CoV555, the observed difference from placebo in the decrease from baseline in the mean log viral load was −0.64 (95% CI, −1.11 to −0.17) (Table 2). The other two doses of LY-CoV555 showed similar improvements in viral clearance at day 3, with a difference from placebo in the change from baseline of −0.42 (95% CI, −0.89 to 0.06) for the 700-mg dose and −0.42 (95% CI, −0.90 to 0.06) for the 7000-mg dose. The difference from placebo in the change from baseline for the pooled doses of LY-CoV555 was −0.49 (95% CI, −0.87 to −0.11).

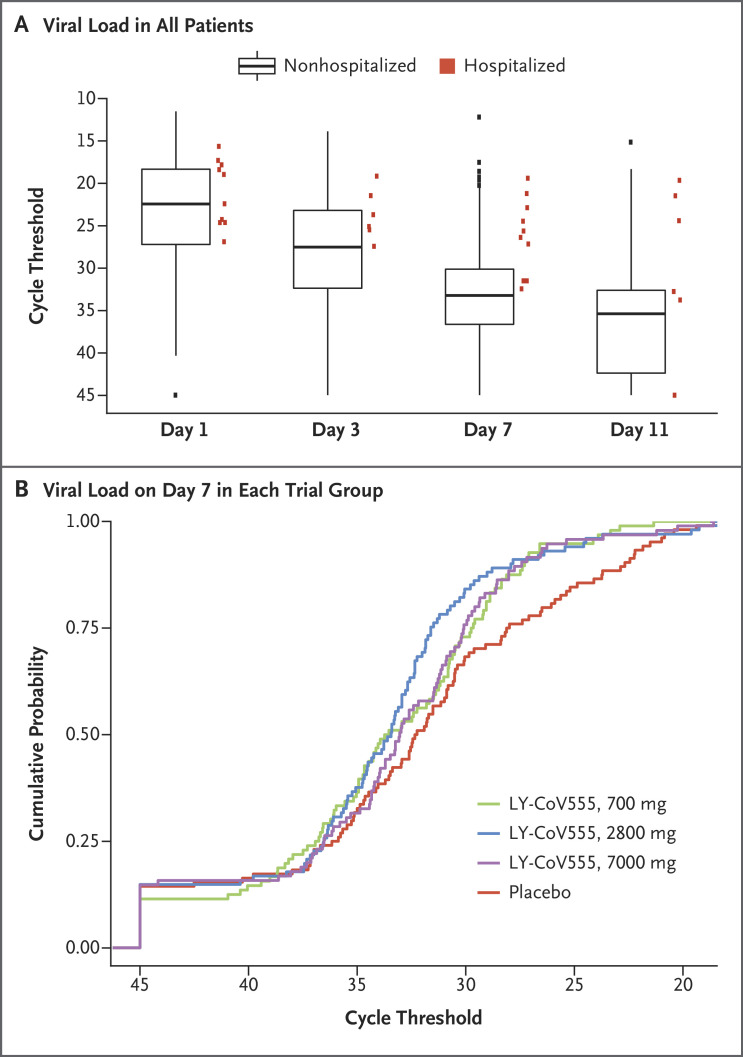

Exploratory Measures of Viral Clearance

In the pooled trial population, an association was observed between slower viral clearance and more hospitalization events. Figure 2A presents the absolute viral load among hospitalized patients (pooled across randomization strata) as well as a box plot of viral loads among nonhospitalized patients. On day 7, all the available measures of viral load among hospitalized patients were higher than the median values among the nonhospitalized patients. Among the patients with a higher viral load on day 7, the frequency of hospitalization was 12% (7 of 56 patients) among those who had a Ct value of less than 27.5, as compared with a frequency of 0.9% (3 of 340 patients) among those with a lower viral load. (The SARS-CoV-2 N1 gene primer determines a Ct value that is equivalent to approximately 570,000 nucleic acid–based amplification tests per milliliter with the use of the SARS-CoV-2 reference panel of the Food and Drug Administration.) Since this difference was not anticipated and emerged from post hoc exploratory analysis, it is unclear whether it would be applicable to other populations. Figure 2B shows the cumulative probability that patients in each trial group would have the indicated cycle threshold of viral load on day 7.

Figure 2. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in All Patients and According to Trial Group on Day 7.

Panel A shows the SARS-CoV-2 viral load (as measured by the cycle threshold on reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay) for all the patients who received either LY-CoV555 or placebo and for whom viral-load data were available at the time of the interim analysis. The box plots indicate the patients who were not hospitalized, and the red squares indicate those who were hospitalized. Such hospital contact was found to be associated with a high viral load on day 7. The boxes represent interquartile ranges, with the horizontal line in each box representing the median and the whiskers showing the minimum and maximum values (excluding outliers that were more than 1.5 times the values represented at each end of the box). Panel B shows the cumulative probability that patients in each trial group would have the indicated cycle threshold of viral load on day 7.

Covid-19–Related Hospitalization

At day 29, the percentage of patients who were hospitalized with Covid-19 was 1.6% (5 of 309 patients) in the LY-CoV555 group and 6.3% (9 of 143 patients) in the placebo group (Table 3). The percentage of patients according to the LY-CoV555 dose who were hospitalized was similar to the overall percentage, with 1.0% (1 of 101) in the 700-mg subgroup, 1.9% (2 of 107) in the 2800-mg subgroup, and 2.0% (2 of 101) in the 7000-mg subgroup. In a post hoc analysis examining hospitalization among patients who were 65 years of age or older and among those with a BMI of 35 or more, the percentage who were hospitalized was 4% (4 of 95) in the LY-CoV555 group and 15% (7 of 48) in the placebo group. Only 1 patient in the trial (in the placebo group) was admitted to an intensive care unit.

Table 3. Hospitalization.*.

| Key Secondary Outcome | LY-CoV555 | Placebo | Incidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| no. of patients/total no. | % | ||

| Hospitalization | 9/143 | 6.3 | |

| 700 mg, 1/101 | 1.0 | ||

| 2800 mg, 2/107 | 1.9 | ||

| 7000 mg, 2/101 | 2.0 | ||

| Pooled doses, 5/309 | 1.6 | ||

Data for patients who presented to the emergency department are included in this category.

Symptom Score

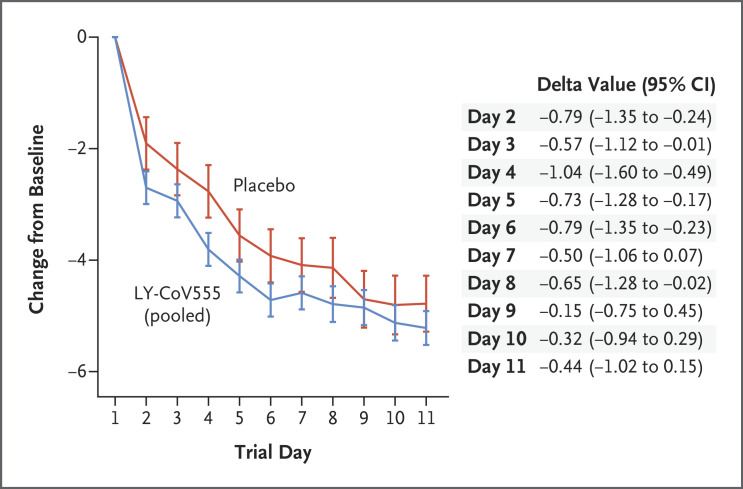

To assess the effect of treatment on Covid-19 symptoms, we compared the change from baseline in symptom scores between the LY-CoV555 group and the placebo group (Figure 3 and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The symptom score ranged from 0 to 24 and included eight domains that were graded from 0 (no symptoms) to 3 (severe symptoms). From day 2 to day 6, the change in the symptom score from baseline was better in the LY-CoV555 group than in the placebo group, with values of −0.79 (95% CI, −1.35 to −0.24) on day 2, −0.57 (95% CI, −1.12 to −0.01) on day 3, −1.04 (95% CI, −1.60 to −0.49) on day 4, −0.73 (95% CI, −1.28 to −0.17) on day 5, and −0.79 (95% CI, −1.35 to −0.23) on day 6. The change from baseline in the symptom score continued to be better in the LY-CoV555 group than in the placebo group from day 7 to day 11, although by these time points most of the patients in the two groups had fully recovered or had only very mild symptoms.

Figure 3. Symptom Scores from Day 2 to Day 11.

Shown is the difference in the change from baseline (delta value) in symptom scores between the LY-CoV555 group and the placebo group from day 2 to day 11. The symptom scores ranged from 0 to 24 and included eight domains, each of which was graded on a scale of 0 (no symptoms) to 3 (severe symptoms). The 𝙸 bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Details about the symptom-scoring methods are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Safety

Serious adverse events occurred in none of the 309 patients in LY-CoV555 group and in 0.7% (1 of 143 patients) in the placebo group (Table 4). The percentage of patients who had an adverse event during treatment was 22.3% (69 of 309) in the LY-CoV555 group and 24.5% (35 of 143) in the placebo group. Diarrhea was reported in 3.2% of the patients (10 of 309) in the LY-CoV555 group and in 4.9% (7 of 143) in the placebo group; vomiting was reported in 1.6% (5 of 309) and 2.8% (4 of 143), respectively. The most frequently reported adverse event in the LY-CoV555 group was nausea (3.9%), whereas diarrhea (4.9%) was the most frequent adverse event in the placebo group. Infusion-related reactions were reported in 2.3% of the patients (7 of 309) in the LY-CoV555 group and in 1.4% (2 of 143) in the placebo group. Most of these events — which included pruritus, flushing, rash, and facial swelling — occurred during the infusion and were reported as mild in severity. No changes in vital signs were noted during these reactions, and the infusions were completed in all instances. In some patients, antihistamines were administered to help resolve symptoms.

Table 4. Adverse Events.

| Adverse Events | LY-CoV555 (N=309) |

Placebo (N=143) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 700 mg (N=101) |

2800 mg (N=107) |

7000 mg (N=101) |

Pooled Doses (N=309) |

||

| number of patients (percent) | |||||

| Serious adverse events* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Adverse events | |||||

| Any | 24 (23.8) | 23 (21.5) | 22 (21.8) | 69 (22.3) | 35 (24.5) |

| Mild | 16 (15.8) | 18 (16.8) | 10 (9.9) | 44 (14.2) | 18 (12.6) |

| Moderate | 7 (6.9) | 3 (2.8) | 8 (7.9) | 18 (5.8) | 16 (11.2) |

| Severe | 0 | 2 (1.9) | 3 (3.0) | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Missing data | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Adverse events according to preferred term† | |||||

| Nausea | 3 (3.0) | 4 (3.7) | 5 (5.0) | 12 (3.9) | 5 (3.5) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.9) | 7 (6.9) | 10 (3.2) | 7 (4.9) |

| Dizziness | 4 (4.0) | 3 (2.8) | 3 (3.0) | 10 (3.2) | 3 (2.1) |

| Headache | 3 (3.0) | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 5 (1.6) | 3 (2.1) |

| Pruritus | 2 (2.0) | 3 (2.8) | 0 | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Vomiting | 1 (1.0) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (1.0) | 5 (1.6) | 4 (2.8) |

| Chills | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 3 (3.0) | 4 (1.3) | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (1.3) | 1 (0.7) |

| Chest discomfort | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (1.0) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 3 (1.0) | 0 |

| Lipase increased | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 3 (1.0) | 0 |

| Thrombocytosis | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 3 (1.0) | 0 |

| Blood pressure increased | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Chest pain | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Hypersensitivity | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Insomnia | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Nasal congestion | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Rash | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Syncope | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) |

The serious adverse event in the placebo group was upper abdominal pain. There were no deaths during the trial.

The preferred terms were defined according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 23.0.

We used standard methods to sequence all viral samples to determine the potential for resistance-associated treatment failure. Accordingly, we assessed the prevalence of variants with resistance to LY-CoV555 that were predicted in preclinical studies. Such variants were present with an allele fraction of more than 20% in at least one sample at any time point in 8.2% of the patients in the LY-CoV555 group (6.3% in the 700-mg subgroup, 8.4% in the 2800-mg subgroup, and 9.9% in the 7000-mg subgroup) and in 6.1% of those in the placebo group. The clinical importance of the presence of these variants is not known.

Discussion

In this preplanned interim analysis of the BLAZE-1 trial, we examined the efficacy of LY-CoV555 in the treatment of mild or moderate Covid-19. The trial was designed to enroll patients with a recent disease onset to evaluate the effect of early intervention with antibody therapy on viral-load biomarkers, symptoms, and severe clinical outcomes, such as hospitalization and death.

Among the patients who received LY-CoV555, the viral load at day 11 (the primary outcome) was lower than that in the placebo group only among those who received the 2800-mg dose. However, a decreased viral load at day 11 did not appear to be a clinically meaningful end point, since the viral load was substantially reduced from baseline for the majority of patients, including those in the placebo group, a finding that was consistent with the natural course of the disease.20,21 However, the evaluation of the effect of LY-CoV555 therapy on patients’ symptoms at earlier time points during treatment (e.g., on day 3) showed a possible treatment effect, with no substantial differences observed among the three doses. It is unclear whether RT-PCR is an accurate measure of viral neutralization, since viral RNA may persist for some time even in the absence of replication-competent virus. Since the severity of illness is primarily driven by lung injury from SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lower respiratory tract, the viral load in the air spaces would be a better reflection of the injury response than the viral load in nasopharyngeal secretions. However, assessments of the lower respiratory tract were not practical owing to precautions that were required in treating these highly infectious patients. Therefore, the nasopharyngeal viral swab was the most pragmatic way of getting a sense of viral load as a surrogate marker of the viral load in the lungs and to correlate with clinical outcomes. However, the nasopharyngeal viral load has not been validated as a predictor of clinical disease course.

An unanticipated observation in this trial was that patients with a higher viral load on day 7 had a higher rate of hospitalization than those with better clearance of viral RNA on day 7, a finding that was consistent with the delayed viral clearance that was observed in patients with more severe disease.20,22,23 On day 7, no hospitalized patient had a viral load that was below the median value of the population. If this observation is prospectively confirmed in future studies, it would suggest the potential for an agent that lowers the viral load to reduce the rate of hospitalization.

To examine the potential of LY-CoV555 to improve Covid-19 clinical outcomes, we evaluated the effect of LY-CoV555 therapy on the frequency of hospitalization, an important outcome given the association between hospitalization and subsequent mortality in patients with Covid-19.23,24 On day 29, the percentage of patients who were hospitalized was 1.6% in the LY-CoV555 group and 6.3% in the placebo group. In a post hoc analysis that was focused on high-risk subgroups (an age of ≥65 years or a BMI of ≥35), the percentage of hospitalization was 4.2% in the LY-CoV555 group and 14.6% in the placebo group.

The data regarding symptoms (as measured by the change from baseline in the symptom score) were also consistent with the hospitalization results, with findings that supported a possible reduction in symptom severity as early as day 2 in the LY-CoV555 group. This effect was maintained over time and across doses, which further supports the validity of a treatment effect on symptoms and suggests a mechanistic link between a lower viral load and a lower frequency of hospitalization. Although the differences in the effects of the three doses of LY-CoV555 were not clear, the 2800-mg dose was the only one to show evidence of accelerated viral clearance. Nevertheless, further studies should continue to assess the efficacy of lower doses.

The safety profile of patients who received LY-CoV555 was similar to that of placebo-treated patients. These data indicate that the treatment is safe. In this interim analysis, the patients who received LY-CoV555 had fewer hospitalizations and a lower symptom burden than those who received placebo, with the most pronounced effects observed in high-risk cohorts. If these results are confirmed in additional analyses in this trial, LY-CoV555 could become a useful treatment for emergency use in patients with recently diagnosed Covid-19.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adam Clooney, Ph.D., of Eli Lilly, for providing medical-writing and other editorial support with an earlier version of the manuscript.

Protocol

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

Data Sharing Statement

This article was published on October 28, 2020, at NEJM.org.

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by Eli Lilly.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Tabata S, Imai K, Kawano S, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in 104 people with SARS-CoV-2 infection on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:1043-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jehi L, Ji X, Milinovich A, et al. Development and validation of a model for individualized prediction of hospitalization risk in 4,536 patients with COVID-19. PLoS One 2020;15(8):e0237419-e0237419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg SKL, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 — COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:458-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalcanti AB, Zampieri FG, Rosa RG, et al. Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin in mild-to-moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 — final report. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman JD, Lye DCB, Hui DS, et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 days in patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spinner CD, Gottlieb RL, Criner GJ, et al. Effect of remdesivir vs standard care on clinical status at 11 days in patients with moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;324:1048-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sims JT, Krishnan V, Chang C-Y, et al. Characterization of the cytokine storm reflects hyperinflammatory endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020. September 10 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bronte V, Ugel S, Tinazzi E, et al. Baricitinib restrains the immune dysregulation in severe COVID-19 patients. J Clin Invest 2020. August 18 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stebbing J, Krishnan V, de Bono S, et al. Mechanism of baricitinib supports artificial intelligence-predicted testing in COVID-19 patients. EMBO Mol Med 2020;12(8):e12697-e12697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dastan F, Saffaei A, Haseli S, et al. Promising effects of tocilizumab in COVID-19: a non-controlled, prospective clinical trial. Int Immunopharmacol 2020;88:106869-106869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farooqi F, Dhawan N, Morgan R, Dinh J, Nedd K, Yatzkan G. Treatment of severe COVID-19 with tocilizumab mitigates cytokine storm and averts mechanical ventilation during acute respiratory distress: a case report and literature review. Trop Med Infect Dis 2020;5:E112-E112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 — preliminary report. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2020;324:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joyner MJ, Senefeld JW, Klassen SA, et al. Effect of convalescent plasma on mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: initial three-month experience. August 12, 2020. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.12.20169359v1). preprint.32817978 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, Zhang W, Hu Y, et al. Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on time to clinical improvement in patients with severe and life-threatening COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;324:460-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baum A, Ajithdoss D, Copin R, et al. REGN-COV2 antibodies prevent and treat SARS-CoV-2 infection in rhesus macaques and hamsters. Science 2020. October 9 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020;181(2):271.e8-280.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones BE, Brown-Augsburger PL, Corbett KS, et al. LY-CoV555, a rapidly isolated potent neutralizing antibody, provides protection in a non-human primate model of SARS-CoV-2 infection. October 1, 2020. (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.30.318972v3). preprint.33024963 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Qi T, Liu L, et al. Clinical progression of patients with COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. J Infect 2020;80(5):e1-e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med 2020;26:672-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Yan L-M, Wan L, et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:656-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim L, Garg S, O’Halloran A, et al. Risk factors for intensive care unit admission and in-hospital mortality among hospitalized adults identified through the U.S. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET). Clin Infect Dis 2020. July 16 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.