Abstract

Abnormal menstruation may result in several pathological alterations and gynaecological diseases, including endometriosis, menstrual pain and miscarriage. However, the pathogenesis of menstruation remains unclear due to the limited number of animal models available to study the menstrual cycle. In recent years, an effective, reproducible, and highly adaptive mouse model to study menstruation has been developed. In this model, progesterone and oestrogen were administered in cycles following the removal of ovaries. Subsequently, endometrial decidualisation was induced using sesame oil, followed by withdrawal of progesterone administration. Vaginal bleeding in mice is similar to that in humans. Therefore, the use of mice as a model organism to study the mechanism of menstruation and gynaecological diseases may prove to be an important breakthrough. The present review is focussed ond the development and applications of a mouse model of menstruation. Furthermore, various studies have been described to improve this model and the research findings that may aid in the treatment of menstrual disorders in women are presented.

Keywords: endometrium, gynaecology, menstruation model, NF-κB, shedding, repair

1. Introduction

Menstruation is a phenomenon unique to females in which vaginal bleeding occurs due to endometrial shedding; this phenomenon commonly occurs in humans, most primates, and other animals (1,2). A normal menstrual cycle in humans consists of proliferative, secretory, and menstrual phases with two peaks of oestrogen secretion and one peak of progesterone secretion. Investigation of the menstrual cycle is a rapidly emerging area of research in reproductive physiology; however, the limited availability of menstruating animals, including higher order primates, elephant shrews, and bats, for scientific research remains a challenge (3–5). Furthermore, the use of these animals to study menstrual physiology is limited owing to their low fertility rates, high feeding cost, and ethical consideration (6). A recent study showed that the spiny mouse is the only naturally menstruating rodent. However, this North African native animal is vulnerable to environmental influences that affect normal menstruation, and its use for menstrual studies is limited due to its unique physiology, and the fact that it lacks antigens and antibodies for its immune response (7). Therefore, commonly used laboratory animals such as mice, which have a high rate of reproduction and clear genetic background, are suitable for in vivo research. Furthermore, they are inexpensive to procure and well-suited for the development of a menstrual model. The present study has reviewed the development of a mouse model of menstruation and its research application, and described the mechanisms of menstruation. A mouse model may be used to simulate various gynaecological complications caused by menstrual disorders in women, including menstrual pain and abnormal uterine bleeding. Platelet-activating factor (PAF) is known to aggravate menstrual pain, and activin serves a role in endometrial repair. These findings complement and validate the results of studies on gynaecological symptoms caused by menstrual abnormalities in females. Therefore, a mouse model of menstruation may provide a strong theoretical foundation for studies on the treatment of reproductive and gynaecological diseases in humans.

2. Mouse model of menstruation

For a long time, previous studies had not attempted to develop a mouse model of menstruation, because mice do not menstruate under normal conditions. However, studies began to investigate new animal models for experimental research to improve understanding of gynaecological diseases. In 1940, Christiaens (8) first transplanted human endometrium into the anterior chamber of a macaque monkey. Subsequently, studies began to investigate the possibility of using the most commonly available mouse to study menstruation (9). Consequently, rodent animals were introduced as experimental models to investigate menstruation.

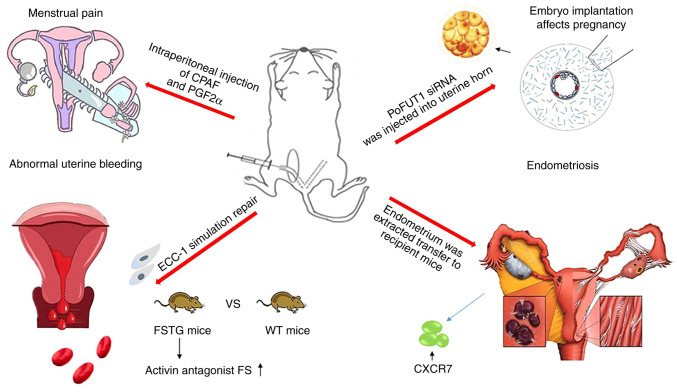

In the 1960s, a mouse model was used to study the mechanism of menstruation (10). In 1984, two distinguished reproductive scientists, C. A. Finn and M. Pope, excised ovaries from mice and treated them with hormones; after they induced decidualization by using oil, they subcutaneously injected progesterone; and by removing progesterone from the mouse endometrium, a mouse endometrial breakdown model was constructed for the first time (11). In 2003, Brasted et al (12) applied a progesterone implant to the mouse menstruation model generated by Finn and Pope. The initiation of progesterone withdrawal was optimized following decidual induction and the model was improved. In 2007, Xu et al (13) used mifepristone (a progesterone receptor antagonist) to block progesterone and induced uterine decidualisation to successfully develop a mouse model of menstruation. In 2009, Kaitu'u-Lino et al (14) used wild-type (WT) mice and mice overexpressing follistatin (a natural activin inhibitor) to study menstruation. In this study, the uterus was excised and cultured in vitro following progesterone withdrawal; subsequently, the human endometrial epithelial ECC-1 cell line was used to simulate repair. This study provided a novel theoretical basis for the clinical treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding. In 2010, Kikuchi-Arai et al (15) used severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)/γCnull (NOG) mice to study menstruation. Following the excision of ovaries, human endometrial fragments were injected subcutaneously into the back of the mice, and periodic hormone therapy was applied to develop an immunodeficient mouse model of the menstrual cycle. This study demonstrated that uterine natural killer (NK) cells do not originate from the peripheral blood, but from the endometrium. In 2014, Cousins et al (16) used a non-surgical embryo transfer device (NSET) to inject sesame oil into the uterine cavity of mice to induce endometrial decidualization, and intraperitoneally injected bromodeoxyuridine prior to sacrifice to develop a modified mouse model of menstrual repair. In the same year, an endometriosis mouse model based on the menstrual model was developed (17). To construct this model, ovaries were excised from mice and periodic hormone therapy was used to induce menstruation. During menstruation, menstrual endometrial tissue of a model with the same genetic background were inoculated into the peritoneum of immunocompetent mice, causing endometriosis. In 2017, De Clercq et al (18) used conventional methods to develop mouse models of menstruation. In this study, transient receptor potential (TRP) channel expression in uterine horns was measured using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction at different time points following discontinuation of progesterone administration to identify factors promoting mouse embryo implantation. In 2018, Peterse et al (19) demonstrated that laparoscopic injection-induced uterine decidualisation is greater than that induced by vaginal injection. Ovariectomized mice were treated with cyclic hormones, following which oil was injected into the uterus using laparoscopy, laparotomy, and vaginal methods. This study demonstrated an optimised method to induce uterine decidualisation in a mouse model of menstruation. In the same year, Hellman et al (20) used WT and platelet-activating factor (PAF)-knockout mice to induce menstruation using conventional methods. In this study, carbamyl PAF (CPAF) and prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) were intraperitoneally injected during menstruation to compare the level of menstrual pain in mice. In 2019, Wang et al (21) demonstrated that the placement of a menstruating mouse model of artificial decidualisation into restraint tubes decreases luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, and progesterone levels in mice under stress, and results in endometrium breakdown and shedding. This study highlighted the effect of pressure on menstrual regulation. Other mouse models of menstruation continue to be investigated.

3. Methods of constructing a hormone induction model

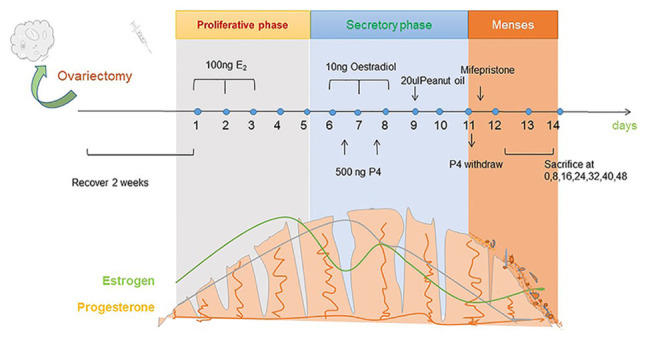

Specific induction of a menstruation model is a complex processs. To begin with, the three requirements for menstruation, hormonal preparation cycle, endometrial decidualisation and progesterone withdrawal, need to be understood (13,22). Multiple models have been developed and improved over the years. In a study by Finn and Pope in 1984 (9), mice ovariectomized under anaesthesia were allowed to recover for one week and subsequently subjected to the following hormone therapy: Intraperitoneal injection of 100 ng oestradiol on days 1 and 2; no hormone administration on days 3, 4, and 5; and injection of 500 µg progesterone and 10 ng oestradiol (each dissolved in 50 µl arachis oil) on days 6 and 7. Simultaneously, 20 µl arachis oil was injected into the uterine horn of 84 mice treated with the aforementioned hormones. Of these, 70 (83%) exhibited decidualisation and marked iris reaction was observed in their uterine horns on day 2 post-injection. In addition, stromal changes, including dilation and congestion of blood vessels, swelling of red blood cells, rupture of blood vessel walls, and blood exudation were observed. These endometrial changes were similar to those observed during menstruation, indicating successful induction of menstruation in mice (11).

Xu et al improved Brasted's model-building method (12,13). Mice were allowed to recover for two weeks after ovariectomy, and were injected with 100 ng 17-B oestradiol (aromatic oil) subcutaneously on days 1, 2, and 3. Mice were administered 50 ng progesterone and 5 ng 17B-E2 in aromatic oil on day 7. On day 9, 20 µl arachis oil was injected into the left corner of the mouse uterus to induce decidualisation. The mice were sacrificed at 0, 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, and 48 h following mifepristone administration. Unlike Finn and Pope, Xu et al optimized the initiation of progesterone withdrawal following the induction of decidualisation and effectively used mifepristone for the first time.

These are two typical methods for constructing mouse menstrual models, which are presented in Fig. 1. Details on the construction of other mouse menstrual models are listed in Table I. The menstrual cycle in mice is similar to that in humans. To begin with, the mice were ovariectomized, the interference of ovarian hormones on the model construction was eliminated, and estrogen was injected (23). The endometrium of the mice began to thicken, and the glands and blood vessels proliferated. After a few days, with the simultaneous injection of progesterone and estrogen, the endometrium and glands continued to grow under hormonal action and secreted mucus to prepare for fertilized egg implantation. Injection of peanut oil into the mouse uterine cavity stimulated the decidualization of the endometrium. Finally, after the progesterone implant was removed, with the rapid decline of hormones, endometrial blood vessels began to spasm; the endometrium became necrotic due to ischemia; and blood and endometrial debris flowed out of the mouse's vagina, forming menstrual blood (24,25).

Figure 1.

Development of a mouse model of menstruation. The mice underwent ovariectomy and were allowed to recover for 2 weeks. Thereafter, they were administered 100 ng oestradiol (stored in peanut oil) on days 1, 2, and 3. The mice did not receive any treatment on days 4 and 5. Subsequently, 10 ng oestradiol and 500 ng progesterone were injected into the uterus on days 6, 7, and 8, and oestradiol was injected on day 9. Next, 20 µl peanut oil is injected to induce uterine decidualisation. After two days, mifepristone was administered to induce progesterone withdrawal and menstruation in mice. The mice were sacrificed at 0, 8, 16, 32, 40, and 48 h after progesterone withdrawal, and the uterine horn was obtained.

Table I.

Comparison of the similarities and differences between different mouse menstrual models.

| Type stage | Year | Ovary removal | Hormone treatment | Induced decidualization | Post-processing | Significance | (Refs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary | 1984 | Yes | Cycle | Oil injected into the | Mice were sacrificed and | Developed mouse | (11) |

| exploration | therapy | uterus | uteri were harvested | endometrial | |||

| of basic | rupture model | ||||||

| menstrual | 2003 | Yes | Cycle | Sesame oil injected | Mice were sacrificed at the | Optimized | (12) |

| models | therapy | into the uterine | time of implant removal 0 | progestin | |||

| horn | and 12, 16, 20, 24, 36, and 48 h | withdrawal time | |||||

| 2007 | Yes | Cycle | Arachis oil was | Mice were sacrificed | Mifepristone | (13) | |

| therapy | injected into the | at different time points | was first used as | ||||

| left uterine horn | following administration of | a progesterone | |||||

| mifepristone | withdrawal | ||||||

| 2014 | Yes | Cycle | Sesame seed oil | Mice received an intra- | A modified mouse | (16) | |

| therapy | was inserted into | peritoneal injection of BrdU | menstrual repair | ||||

| the uterine by | 90 min before being | model | |||||

| NSET | sacrificed | ||||||

| 2018 | Yes | Cycle therapy | Oil was injected in the uterus via laparotomy, laparoscopy or vagina | Progesterone withdrawal, followed by hysterectomy after 4 to 6 h | Identified the best way to induce uterine decidualization | (19) | |

| Improvement | 2009 | Yes | Cycle | Sesame oil was | Mice were sacrificed 24 | Discover possible | (14) |

| of menstrual | therapy | injected into the | or 48 h after progesterone | targets for treating | |||

| model to | lumen of the right | removal and the uterus was | abnormal uterine | ||||

| simulate | uterine horn | removed for in vitro analysis | bleeding | ||||

| clinical | and simulation of repair | ||||||

| disease | 2014 | Yes | Cycle | Oil was injected | The endometrium of | Successful | (17) |

| therapy | into the uterine | artificially induced | induction of | ||||

| horn | menstruation was transferred | endometriosis | |||||

| to the peritoneum of recipient | based on a | ||||||

| mice to induce endometriosis | menstrual model | ||||||

| 2017 | Yes | Cycle | Vaginal intra- | Uteri were harvested at | Study the | (18) | |

| therapy | uterine injection of | different time points to | factors affecting | ||||

| sesame oil | study the expression of TRP | mouse embryo | |||||

| channels | implantation | ||||||

| 2018 | Yes | Cycle | Oil was injected | Intraperitoneal injection | Improvement of | (20) | |

| therapy | into the uterine | of CPAF and PGF2 | menstrual pain | ||||

| horn | during artificially induced | research based on | |||||

| menstruation in mice | a menstrual model |

TRP, transient receptor potential; CPAF, carbamyl PAF; PGF2, prostaglandin F2.

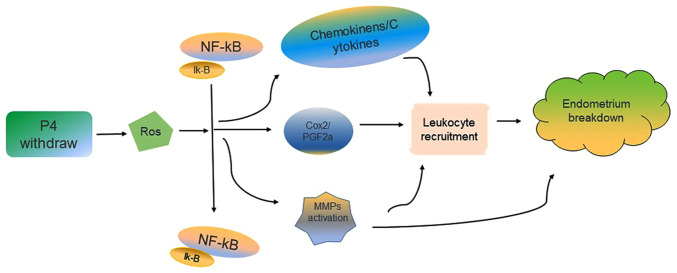

4. Role of NF-κB signalling pathways in endometrial shedding

Progesterone withdrawal may lead to endometrial breakdown and loss during the establishment of a mouse model. However, the physiological significance of downstream processes, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and other antioxidants in the female reproductive system are not known. ROS have been reported to serve an important role in menstruation (Fig. 2). Wu et al have developed a mouse model of menstruation based on the method of Brasted et al (12,13). In this model, the reactive oxygen scavenger, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), was intraperitoneally injected at different doses prior to discontinuation of progesterone administration. The ROS assay and histological analysis following uterine collection demonstrated that ROS levels may affect endometrial breakdown. NAC, p65, and p50 may affect NF-κB activation by regulating its nuclear and cytoplasmic expression. In addition, several leukocyte chemokines are regulated by NF-κB, the source of the beginning of ROS (26). The Cox-2 promoter binds to NF-κB and regulates gene transcription. The in vitro, in vivo, and molecular analysis results of NF-κB-Cox-2 signal transduction, as well as the antioxidant NAC, has been used to determine the role of ROS in menstruation; ROS are the key regulators of endometrial breakdown as they regulate the downstream NF-κB signal (27).

Figure 2.

ROS regulates endometrial breakdown through the NF-κB-Cox-2 signaling. Progesterone withdrawal may lead to increased ROS, which will activate the NF-B-Cox-2 signal through the classic IKK-dependent pathway and increase Cox-2. At the same time, the NF-κB signaling also regulates chemokinens, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases, thereby promoting the breakdown of the endometrium and the formation of menstruation. ROS, reactive oxygen species; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; Cox-2, cyclooxygenase 2.

MMPs may be broken down during menstruation, and MMP9 is the first component that is degraded (28). In addition to ROS, RU486 may induce endometrial breakdown. After the progesterone hormone level was reduced, NF-κB was activated, which induced the expression of the downstream target genes (includings MMP9) and binding to the promoter of MMP9, further promoting the breakdown and shedding of the mouse endometrium. The mouse model of menstruation may also be used to determine the kinetics of endometrial breakdown and regeneration during endometrial reconstruction (26).

5. Initiation of menstruation

Endometrial breakdown

The endometrium is the layer that forms the inner lining of the uterus in mammals. It is markedly affected by the cyclic changes in oestrogen and progesterone levels, and undergoes proliferation, differentiation, breakdown, and repair simultaneously (29). The construction of the mouse model mimics this process. A rapid decrease in progesterone levels may lead to a series of molecular changes, including spiral artery constriction; increased production of inflammatory cells, including white blood cells, neutrophils, and prostaglandins; and MMP activation, leading to breakdown and disintegration of the endometrium (15,30). Progesterone withdrawal is an important event that initiates endometrial breakdown and shedding, and promotes cell-factor and factor-factor interactions. The mouse model of menstruation is a reliable tool to understand the molecular mechanism of endometrial breakdown.

In order to morphologically confirm the induction of menstruation, mice are subjected to vaginal smear testing and eosin staining following discontinuation of progesterone administration. The presence of erythrocytes and degeneration of decidual stroma in the vaginal smear are suggestive of menstruation. While nuclear rupture or constriction may be clearly observed, cytoplasmic degeneration and cytoplasmic boundary resolution are not obvious. The uterine horn shows considerable hypertrophy and hyperemia compared with that in the control group, in which the uterine horn is pale pink. Blood clots, similar to those noted during human menstruation, may be observed in the uterus. However, no spiral artery remodeling is observed during menstruation in induced mice, which is slightly different from human menstruation (Table II) (6,24,31).

Table II.

Comparison of human menstruation and mouse model menstruation.

| Characteristics | Human | Mouse model |

|---|---|---|

| Reproductive tract | Simplex uterus with fundal body and fallopian tubes | Bicornuate uterus with uterine horn oviducts |

| Menstrual cycle | Natural (28 days) | Artificially induced |

| Breeding season | Continuous | Continuous |

| Length of menses | 5–7 days | 5–7 days |

| Shedding | Menstrual waves | Menstrual waves |

| Decidualisation | Sponstaneous | Artificially induced |

| Decidua characteristics | Gentleness and regularity | Rapid and destructive |

| Glands | Epithelial and intrauterine | Epithelial and intrauterine |

| Oestrogen peak | During proliferative and secretory phase | Artifician induction |

| Spiral artery remodelling | Yes | No |

| Immune response | Yes | Yes |

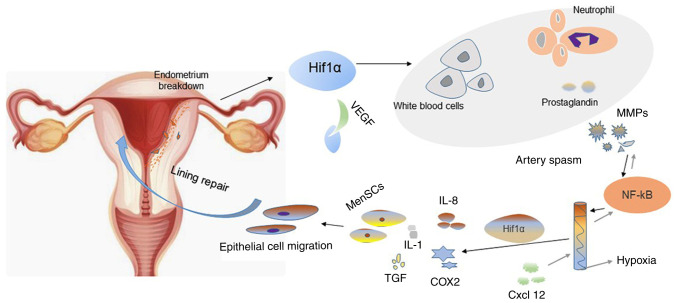

Regarding menstruation, it has been proposed that P4 causes two stages of after withdrawal: P4-dependent and P4-independent (32). The critical period of progesterone withdrawal is earlier than the breakdown and shedding of the endometrium in the menstrual model. However, whether or not there is an association between endometrial breakdown and decidual status remains unknown. The decidual state of the mouse model is different from that in humans. In the mouse model, reticular fibre staining and histomorphological analysis were used to evaluate endometrial status. During endometrial shedding, the predecidual-like zone (PZ) is actively degraded (33). Furthermore, inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) confirmed its role in endometrial breakdown; HIF-1α may regulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression (Fig. 3). Therefore, regulation of VEGF mRNA levels may be considered an early factor to modulate endometrial breakdown. However, HIF-1 may regulate the expression of VEGF mRNA for a long time (34). Hypoxia and HIF-1α activation are induced by progesterone withdrawal, and hypoxia may upregulate MMP expression. However, hypoxia is not essential for endometrial breakdown (35).

Figure 3.

Cellular and molecular changes during endometrial breakdown and repair. Progesterone withdrawal may promote endometrial shedding and cause menstruation. The binding of activated HIF-1α to VEGF angiogenic factors in the endometrial during endometrial breakdown results in increased production of white blood cells, neutrophils, inflammatory cells, and prostaglandins. The activation of NF-kB causes the decline of MMPs, and the process is reversible. Spiral arteriolar muscular contraction leads to anoxia in the endometrium during endometrial breakdown. Endometrial repair under anaerobic conditions may result in increased expression of IL-8 and Cox2 as well as increased leukocyte infiltration of cytokines (e.g., IL-1) and growth factors (e.g., transforming growth factor). The increase in the number of menstrual blood-derived cells and migration of epithelial cells further promotes rapid repair of the endometrium. HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; IL, interleukin; Cox-2, cyclooxygenase 2.

Repair regulation

In humans, each menstrual cycle exhibits a unique pattern of tissue damage, followed by rapid tissue repair without scar tissue formation (36). For understanding repair regulation, at present, two different methods of tissue shedding are mainly used to induce mouse models. One of the most commonly used models is the first proposed by Finn and PoPe, with was later modified by Salamonsen et al to optimize the time of endometrial shedding repair (12,23,37).

In the 1970s, a study demonstrated that epithelial cells from the exposed end of glands and stromal tissue surface may proliferate simultaneously, suggesting their involvement in endometrial repair (38). The mouse models used to study the complete endometrium repair mechanism showed that the dynamics of the rapid healing of endometrial serve a supporting role in the cycle, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and epithelial cell migration were observed 4–12 h after progesterone withdrawal (16). In a recent study by Patterson et al (39), female mice were mated with vasectomized male mice to induce pseudopregnancy. Thereafter, the female mice were oophorectomized and subjected to progesterone withdrawal to induce menstruation. The number of cells co-expressing keratin and vimentin were increased by two-fold 24 h after ovariectomy (39). These results indicated that epithelial-mesenchymal transition and epithelial cell migration may greatly enhance endometrial repair, providing a new basis for the treatment of abnormal endometrial repair.

Constriction of the uterus and decidual spiral arterioles during menstruation forms a hypoxic uterine environment. Furthermore, it is not known whether oxygen deprivation may affect endometrial repair. Under normoxia, cell sensors may hydroxylate certain proline residues in HIF-1α (40). In the mouse menstrual model, bleeding and physiological anoxia of the endometrium occur. HIF-1α has also been found to alleviate hypoxia-induced delayed endometrial repair in mice via pharmacological activity. Furthermore, hyperoxia may delay endometrial repair by downregulating HIF-1α (41). Cousins et al (42) recorded uterine breakdown and repair over a 24-h period in mice and measured oxygen tension in the uterus in real time. This study reported that the number of epithelial cells varied under hypoxia. In addition, spatiotemporal variations and changes in the expression of VEGF and the angiogenesis gene encoding matrix-derived factor, a receptor for chemokine ligand (CXCL12) mRNA regulation, may affect hypoxia. These results suggested that hypoxia-induced gene regulation during endometrial rupture is similar to that during menstruation (42). Nonetheless, hypoxia and ischemia caused by spiral artery spasm following progesterone withdrawal may cause endometrial breakdown. However, hypoxia did not induce endometrial shedding and repair 21 days after endometrial transplantation in ovariectomized severe combined immunodeficient mice. This suggested that hypoxia may not serve a role in endometrial breakdown and repair in xenograft mouse models (43).

A recent study demonstrated that the absence of neutrophils may significantly inhibit uterine reconstruction of menarche in a mouse model of menstruation (44). Furthermore, inflammatory mediators and granulocytes may promote local tissue remodelling of the uterus (45). White blood cells are required in tissue repair 4 to 5 days prior to menstruation in females; furthermore, progesterone withdrawal may upregulate inflammatory mediators, including NF-κB, monocyte chemoattractant peptide 1 (MCP-1), interleukin 8 (IL-8), and cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox-2) (46).

Previous studies have reported that MMPs (specific proteases that bind to all components of the extracellular matrix) serve an important role in menstruation (47,48). In a mouse model of endometrial repair, the uterus was removed at different time points following progesterone withdrawal and MMP expression was measured. The results demonstrated that MMP expression in the endometrium was significantly increaseed during the menstrual and pre-menstrual periods than during other stages of the menstrual cycle. However, MMP inhibitors (batimistat and doxycycline) had no significant effect on endometrial repair in mice; therefore, MMPs may not be the key mediators of endometrial breakdown and repair (49). Androgens serve an important role in endometrial repair in menstruating mice. The administration of a single dose of androgen may cause spatiotemporal changes in the expression of caspase-3 and MMP3 or MMP9. Furthermore, androgen receptor (AR)-dependent regulation of MMPs is known to accelerate endometrial tissue repair. Therefore, AR may be a potential drug target for abnormal endometrial repair (50). Transcriptional regulation of these factors during endometrial repair is important to understand the mechanism of endometrial repair.

6. Applications of a mouse model of menstruation

Menstrual pain

Although the development and precise mechanism of normal menstruation are vaguely understood, pathological changes occurring during abnormal menstruation are not yet known. The development of a mouse model of menstruation may provide valuable insight into various gynaecological symptoms or diseases. Endocrine disorders may lead to menstrual disorders, including dysmenorrhoea and abnormal bleeding (51,52). Dysmenorrhoea is one of the most common gynaecological conditions. Approximately 40–70% of females of reproductive age, both students and working professionals, are significantly affected by the adverse effects of menstrual pain. Furthermore, menstrual pain may cause other pelvic diseases (53).

The mechanism and aetiology of menstrual pain is different. Mice with menstrual pain have increased levels of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α; Table III) (54). Platelet-activating factor (PAF) levels are not significantly affected by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. PAF receptor agonist CPAF and PGF2α may increase intrauterine pressure. WT and mice treated with the PAF receptor knockout agent were used to construct a menstrual model, and several parameters, including stretching, rubbing abdomen on the floor, nongrooming licking, and arched posture were implemented to assess the pain level of mice. Intraperitoneal injection of CPAF and PGF2α into WT mice during menstruation caused pelvic hyperalgesia and visceral pain. (Fig. 4) However, no pain was detected in PAF receptor-knockout mice. CPAF may cause ischemia by causing endometrial contraction, which may affect menstrual pain in mice. In addition, CPAF may reduce oxygen saturation and aggravate hypoxia in the uterus (20). Furthermore, injection of sildenafil into the uterus of rats in the oestrous phase increased blood flow to the uterus and decreased dysmenorrhoea. However, the effects of ischemia and hypoxia on uterine physiology remain controversial. Steady-state electrode recording often ignores the effect of contraction (55). The use of mouse models may provide a new experimental basis for developing novel targets to study uterine contractile force, inflammatory precursors, and tissue oxygenation.

Table III.

Changes and roles of cytokines at the pathological level.

| Clinical category | Molecular pathology | Impact | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menstrual pain | PGF2a | Acceleration of endometrial contraction | Increased |

| CPAF | Aggravation of anoxia | Increased | |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | Follistatin | Promotion of repair | Decreased |

| DuP-697/indomethacin | Suppression of menstruation | Decreased | |

| Cox-2 | Inflammatory response | Increased | |

| Endometriosis | CXCR7 | Induction of endometriosis | Increased |

| K:F9 | Promotion of activity | Increased | |

| KLF13 | Participation in the pathological process | Decreased | |

| TFF3 | Differential marker | Increased | |

| Iron deposit | Erythrocytosis/excess iron storage | Increased | |

| Successful embro implantation | ESC decidua | Secretion of factors | Increased |

| poFUT1 | Promotion of endometrial decentralization | Increased | |

| TRP | Embryo implantation | Increased | |

| Tiam1 | Regulation of decidua | Increased | |

| Omega-3 | Facilitation of embryo implantation | Increased | |

| MSX1 | Control of embryonic development | Increased |

PGF1a, prostaglandin F2α; CPAF, carbamyl PAF; Cox-2, cyclooxygenase-2; KLF13, Krüppel-like factor; TFF3, three-leaf factor 3; ESC, endometrial stromal cells; poFUT1, protein o-fucosylation; TRP, transient receptor potential.

Figure 4.

Applications of a mouse model of menstruation. Following ovariectomy and hormone therapy, CPAF was injected into the abdominal cavity of wild-type mice to induce visceral pain and pelvic hyperalgesia, to mimic menstrual pain in women. A mouse model of overexpressed follistatin (a natural inhibitor of activin) and a human endometrial epithelial cell line (ECC-1) were used to simulate endometrial repair. Activin significantly accelerated wound healing. Therefore, activin may be used as a potential drug target to treat irregular uterine bleeding. In another mouse model of menstruation, poFUT1 siRNA was injected into the uterine horn to extract the endometrium. The poFUT1 expression was increased during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. However, poFUT1 expression in the endometrium during miscarriage was low. Therefore, poFUT1 may be a potential therapeutic target and diagnostic marker for miscarriage. Similarly, the endometrial fragments obtained from menstruating mice were transplanted subcutaneously into the back of mice to simulate retrograde menstruation in mice to induce endometriosis in order to further study the pathological changes and mechanism of endometriosis. CPAF, carbamyl PAF; poFUT1, protein o-fucosylation.

Abnormal uterine bleeding

Abnormal uterine bleeding is caused by insufficient or incorrect repair of the endometrium following menstruation, and it is often accompanied by initial cell damage and white blood cell cascade inflammation (14,47).

The role of activin in promoting wound healing in mouse endometrium has been confirmed previously (56). Therefore, WT mice and mice overexpressing follistatin (a natural inhibitor of activin) were used to develop a hormone therapy-induced endometrial breakdown/repair model in ovariectomized mice. Furthermore, ECC-1 cells were used to simulate endometrial repair, and activin was shown to promote wound closure. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of follistatin on endometrial repair in mice overexpressing follistatin was significantly slower than that in WT mice, suggesting that activin may promote endometrial repair (14).

In 2016, Cousins et al (50) constructed a mouse menstrual model. Following progesterone withdrawal, androgens were injected, and androgens had a significant effect on the regulation of persistent vaginal bleeding in mice (50). Furthermore, beta-alpha and beta-beta immunolocalization were performed on the endometrium of mice, and staining of certain white blood cells and specific epithelium was detected adjacent to the repair site of the endometrium. The localization of the endometrial repair site in the mouse model was the same as that in humans during menstruation, with an influx of numerous white blood cells (57). These findings may aid in understanding the pathological mechanism of abnormal uterine bleeding.

Cyclooxygenase inhibitors have been frequently used to treat abnormal uterine bleeding (58). In a mouse menstrual model, the administration of DuP-697 (Cox-2 inhibitor), indomethacin (Cox-1 and Cox-2 inhibitor), and pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (NF-κB inhibitor) was reported to inhibit menstruation in mice. The appearance of CD45+ significantly decreased the number of blood cells, and PGs induced by NF-κB/Cox-2 may regulate the inflow of white blood cells, thereby causing endometrial breakdown. Therefore, it may provide a novel drug target for abnormal uterine bleeding (59).

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is an oestrogen-dependent gynaecological disease that is caused by the implantation of viable endometrial cells outside the endometrium. The most common manifestations of this disease are progesterone resistance and abnormal oestradiol signalling (60). Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and extrauterine stroma. Sampson's theory of retrograde menstruation explains the pathogenesis of majority endometriosis caused by the pelvic implantation of living endometrial cells following tubal regurgitation, during menstruation (61). However, the frequency with which menstrual retrograde flow is associated with other factors is unknown. One possibility to compensate for menstrual deficiencies in a rodent model is to use a mouse model for preclinical studies of menstruation and excessive menstrual bleeding in humans.

Peterse et al (19) induced endometrial decidualization in ovariectomized C57 mice by laparotomy and subperitoneal oil injection following hormone therapy. More than 80% of animals exhibited macroscopic bicornuate decidualization following stimulation with laparotomy or laparoscopy. Next, the decidual and endometrial membranes of the donor mice were transplanted into the recipient mice to induce endometriosis, thereby simulating the process of retrograde menstruation, a key event in the pathogenesis of endometriosis (19). Similarly, Greaves et al (17) transplanted endometrium from the same menstrual cycle into the peritoneum of mice and successfully developed a mouse model of endometriosis. They also demonstrated that increased expression of oestrogen receptors and macrophages may produce an inflammatory microenvironment during endometriosis. These events are very similar to those occurring in humans. Therefore, the development of such a model may provide novel therapeutic alternatives for the treatment of endometriosis (17).

CXCL12 is an inflammatory chemokine that participates in various cellular processes, including proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis. CXCR7 is the receptor for CXCL12 and contains a GPCRC-X-C sequence. Pluchino (62) determined the expression and localization of CXCR7 in endometriotic tissues by using a mouse model of menstruation. CXCR7 expression was revealed to be low or undetectable in normal endometrial epithelial cells and stromal cells at various stages of the human menstrual cycle. However, CXCR7 was upregulated in endometriotic tissues, and the staining of blood vessels and glands was more notably. CXCR7-overexpression was also observed in different cell populations in the microenvironment. Therefore, CXCR7 may be a potential target for the treatment of endometriosis. Further studies are required to validate this finding (62). As members of the SP/KLF transcription factor family, Krüppel-like factor (KLF)9 and KLF13 are involved in the regulation of tissue development and proliferation, as well as programmed cell apoptosis. The absence of KLF9 has been demonstrated to be beneficial for the development of endometriosis; however, the rate of endometriosis differs slightly in KLF13-deficient mice. Nonetheless, the total numbers of progesterone receptors, oestrogen receptors and ESR1 (RNA and immune reactive protein) are low. Therefore, KLF13 may be involved in the pathological process of endometriosis (60).

Iron deposits are often found in endometriotic lesions. These deposits accumulate due to the reversal of blood cells during menstruation. In a study by DeFrere et al nude mice were injected with human menstrual endometrium or other iron chelating agents, including ferric oxide and red blood cells. Injection of the desferrioxamine (DFO) group with red blood cells more effectively decreased iron deposits and pathological changes in macrophages, indicating that iron overload may induce the growth of endometrial tissue, but had no clear effect on the formation of endometriosis. Administration of desferrioxamine may prevent pelvic iron overload, reduce continued cell proliferation, and treat endometriosis (63,64).

Embryo implantation affects pregnancy

According to a World Health Organization survey, 10–18% of couples are currently undergoing infertility treatments, and 48 million women are affected by infertility (65). Failure of embryo implantation is an important cause of infertility; embryo implantation involves a series of cellular and molecular biological events from blastocyst implantation. Successful embryo implantation into the endometrium requires decidualisation of endometrial stromal cells (66). Decidual cells may synthesize and secrete growth factors, chemokines, signalling factors, and cytokines, all of which are required for embryo implantation and placenta formation. Impaired mesenchymal differentiation in the endometrium may cause various pregnancy-related problems, including repeated miscarriage, preeclampsia, infertility, and intrauterine growth restriction (67,68).

Embryo implantation serves an important role in the female reproductive process. The interaction between the embryo and uterus is facilitated by a combination of various factors, including the endometrium, hormones, and prostaglandins (69,70). However, endometrial stromal cell decidualisation serves an important role in promoting embryo implantation and development, leading to successful embryo formation (71). A mouse model of menstruation was developed in which protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 (poFUT1) siRNA was injected into the uterine horn to extract the endometrium. The poFUT1 expression was revealed to increase during the proliferation phase of the menstrual cycle; however, poFUT1 expression was reported to decrease in the endometrium during miscarriage. These results indicated that poFUT1 serves a key role in endometrial decidualisation, and may be therapeutically targeted to prevent spontaneous abortion (72).

Transient receptor potential (TRP) is an important signaling channel in human endometrial decidua and embryo implantation. De Clercq et al (68) established a menstrual model by regulating hormones to analyze TRP channels in mice. The mice in the natural estrous or during an induced menstrual cycle exhibited a similar TRP channel expression pattern in stromal and epithelial cells, and epithelial cells showed significant expression of TRPV6, TRPM6, and TRPV4, whereas TRPC6, trpc1/4, and TRPV2 were mainly expressed in stromal cells. The development of mouse models may be an effective approach for research in the field of reproduction (18). Research on mouse menstrual models revealed that the upregulation of miR-22 and the downregulation of Tiam1/Rac1 signal may inhibit mouse embryo implantation (73).

Omega-3 is an essential fatty acid that serves an important role in relieving primary dysmenorrhoea (2) and may increase embryo implantation rate by promoting endometrial perfusion. Omega-3 supplementation during the menstrual cycle prior to mating in mice significantly increased immunomodulatory activity of the adenoepithelial basement membrane, endometrial stromal adhesion protein, lumen epithelial basement membrane, and leukaemia inhibitory factor in the high-dose group. It also decreased the height of microvilli and epithelium, thereby providing a conducive environment for endometrial implantation. Omega-3 supplementation promotes embryo implantation and supports healthy reproduction (74). In addition, the endocannabinoid system (eCS) serves a crucial role in maintaining pregnancy because CB1-KO mice are resistant to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced early embryonic resorption. Furthermore, the eCS promotes luteal degeneration, which may be associated with LPS-induced serum progesterone withdrawal. Therefore, the harmful effects of LPS on the reproductive system may be inhibited by the eCS (75).

The muscle segment homeobox genes MSX1 and MSX2 encode transcription factors that regulate the interaction between organs, tissues, and genes during embryonic development (76). Human MSX1 protein expression in the endometrium was increased during the early stage of the secretion phase of the menstrual cycle, and MSX1 expression in the glands was decreased in the middle and later stages of secretion. Biopsies of infertile patients exhibited low MSX1 expression. Bolnick et al (77) developed a mouse model and demonstrated that MSX1 is highly expressed in the uterus of mice capable of uterine implantation. The implantation rate significantly decreases upon MSX1 downregulation. Additionally, the absence of the homologous box protein may markedly reduce the loss of polarity of epithelial cells during implantation, thereby causing sterility. Therefore, these molecules may be potential targets for birth control pills (77).

7. Discussion and perspective

Laboratory mice exhibit super fecundity. Mice with a pregnancy of >20 days may give birth to a litter of 2–14 pups (78). This rapid rate of reproduction and strong adaptability make them an ideal laboratory animal model. Although mice do not menstruate in their natural state, they have been used frequently to study menstruation under artificial intervention and controlled experimental conditions. The mouse model of menstruation allows simulation of gynaecological diseases caused by abnormal menstruation (79).

Various pathological symptoms caused by abnormal menstruation adversely affect human life and work. Pathological mechanisms, diagnostic targets, and effective drug development require extensive studies and detailed investigation. Only a few animals naturally menstruate. In addition, due to slow reproduction rates and lack of targeted antibodies and other factors, naturally menstruating animals cannot be widely popularized in practice and fail to meet the requirements of current scientific research. The mouse model of menstruation not only overcomes these limitations, but is relatively easy to construct. Furthermore, the technology may be improved and advanced. For example, Finn and Pope's initial model (11) has been used to develop other models (17,19), including the endometriosis model developed by transplanting the human endometrial tissue into the mouse uterus. These models may be used effectively to study pathological changes and mechanisms of various gynaecological diseases, thereby providing a strong theoretical basis for the further development of diagnostic targets and targeted drugs. Since the 1980s, valuable progress has been achieved in the investigation of effective models of menstruation. Certain important factors and mechanisms require further study to understand the pathogenesis of diseases. For example, the NF-κB signalling pathway has been confirmed to be involved in the initiation of menstruation. miR-22 upregulation inhibits uterine implantation in mice. Therefore, drugs targeting miR-22 may promote successful embryo implantation. Although the common pathological changes in endometriosis are known, the specific mechanisms remain unclear. Therefore, further research is required to elucidate these mechanisms.

The development of a mouse model of menstruation may greatly influence menstrual research and is now increasingly favoured. Despite its clear advantages, there are certain controversies regarding its limitations and challenges. Artificially induced menstruation is reproducible and easy to maintain, and immune response during menstruation in mice is similar to that in humans. However, this model does not exhibit natural decidualisation and physiological menstruation. Endometrial decidualisation under experimental intervention is extensive, rapid and destructive. Furthermore, spiral artery remodelling does not occur prior to menstruation in this mouse model. This is a significant difference when compared with the physiological process of human menstruation. Furthermore, the development of a mouse model requires long experimental periods and complex techniques. Further studies are required to conceive a better method to successfully construct a mouse model that accurately mimics human menstruation and may be used for research in an effective and efficient manner. Nevertheless, other naturally menstruating animals are also worth investigating to study menstrual mechanisms and gynaecological diseases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BK

bradykinin

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- Cox-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- CXCL

a receptor for chemokine ligand

- CB1-KO

cannabinoid receptor type 1 knockout

- ECC-1

endometrial epithelial cell line

- ESR

estrogen receptor

- ESCs

endometrial stromal cells

- eCS

endocannabinoid system

- GPCRs

G-protein-coupled receptors

- HIF1

hypoxia-inducible factor-1

- HESCs

human endometrial stromal cells

- IL-8

interleukin 8

- KLF

Krüppel-like factor

- LIF

leukemia inhibitory factor

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein

- MSX

muscle segment homeobox gene

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- PR

progesterone receptor

- PGF2α

prostaglandin F2α

- PG

prostaglandin

- PAF

platelet-activating factor

- poFUT1

protein o-fucosylation

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SAMP8

senescence-accelerated mouse prone-8

- TFF3

three-leaf factor 3

- Tiam1

T-lymphoma invasion and metastasis factor 1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31900852 to HL), Nanchang University (grant no. PY201801 to HL), and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (grant nos. 2018BAB215012 and 20192ACB21026 to HL).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

HL, TL, FLS, YY, QFC, and ZMT were responsible for study review, conception and design. TL and HL drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bellofiore N, Evans J. Monkeys, mice and menses: The bloody anomaly of the spiny mouse. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:811–817. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1390-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahbar N, Asgharzadeh N, Ghorbani R. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids on intensity of primary dysmenorrhea. Int J Gynaecol Obstetrics. 2012;117:45–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellofiore N, Ellery SJ, Mamrot J, Walker DW, Temple-Smith P, Dickinson H. First evidence of a menstruating rodent: The spiny mouse (Acomys cahirinus) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:40.e1–40.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasweiler JJ., VI Spontaneous decidual reactions and menstruation in the black mastiff bat, molossus ater. Am J Anat. 1991;191:1–22. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001910102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasweiler JJ VI, de Bonilla H. Menstruation in short-tailed fruit bats (Carollia spp.) J Reprod Fertil. 1992;95:231–248. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0950231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng CW, Bielby H, Licence D, Smith SK, Print CG, Charnock-Jones DS. Quantitative cellular and molecular analysis of the effect of progesterone withdrawal in a murine model of decidualization. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:871–883. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.057950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellofiore N, Rana S, Dickinson H, Temple-Smith P, Evans J. Characterization of human-like menstruation in the spiny mouse: Comparative studies with the human and induced mouse model. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1715–1726. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christiaens GC. J.E. Markee: Menstruation in intraocular endometrial transplants in the rhesus monkey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1982;14:63–65. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(82)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finn CA, Keen PM. The induction of deciduomata in the rat. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1963;11:673–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn CA, Hinchliffe JR. Reaction of the mouse uterus during implantation and deciduoma formation as demonstrated by changes in the distribution of alkaline phosphatase. J Reprod Fertil. 1964;8:331–338. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0080331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn CA, Pope M. Vascular and cellular changes in the decidualized endometrium of the ovariectomized mouse following cessation of hormone treatment: A possible model for menstruation. J Endocrinol. 1984;100:295–300. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1000295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brasted M, White CA, Kennedy TG, Salamonsen LA. Mimicking the events of menstruation in the murine uterus. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1273–1280. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.016550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu XB, He B, Wang JD. Menstrual-Like changes in mice are provoked through the pharmacologic withdrawal of progesterone using mifepristone following induction of decidualization. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:3184–3191. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaitu'u-Lino TJ, Phillips DJ, Morison NB, Salamonsen LA. A new role for activin in endometrial repair after menses. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1904–1911. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kikuchi-Arai M, Murakami T, Utsunomiya H, Akahira JI, Suzuki-Kakisaka H, Terada Y, Tachibana M, Hayasaka S, Ugajin T, Yaegashi N. Establishment of long-term model throughout regular menstrual cycles in immunodeficient mice. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;64:324–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cousins FL, Murray A, Esnal A, Gibson DA, Critchley HO, Saunders PT. Evidence from a mouse model that epithelial cell migration and mesenchymal-epithelial transition contribute to rapid restoration of uterine tissue integrity during menstruation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greaves E, Cousins FL, Murray A, Esnal-Zufiaurre A, Fassbender A, Horne AW, Saunders PT. A novel mouse model of endometriosis mimics human phenotype and reveals insights into the inflammatory contribution of shed endometrium. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1930–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Clercq K, Van den Eynde C, Hennes A, Van Bree R, Voets T, Vriens J. The functional expression of transient receptor potential channels in the mouse endometrium. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:615–630. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterse D, Clercq K, Goossens C, Binda MM, Dorien FO, Saunders P, Vriens J, Fassbender A, D'Hooghe TM. Optimization of endometrial decidualization in the menstruating mouse model for preclinical endometriosis research. Reprod Sci. 2018;25:1577–1588. doi: 10.1177/1933719118756744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellman KM, Yu PY, Oladosu FA, Segel C, Han A, Prasad PV, Jilling T, Tu FF. The effects of platelet-activating factor on uterine contractility, perfusion, hypoxia, and pain in mice. Reprod Sci. 2018;25:384–394. doi: 10.1177/1933719117715122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SF, Chen XH, He B, Yin DD, Gao HJ, Zhao HQ, Nan N, Guo SG, Liu JB, Wu B, Xu XB. Acute restraint stress triggers progesterone withdrawal and endometrial breakdown and shedding through corticosterone stimulation in mouse menstrual-like model. Reproduction. 2019;157:149–161. doi: 10.1530/REP-18-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emera D, Romero R, Wagner G. The evolution of menstruation: A new model for genetic assimilation: Explaining molecular origins of maternal responses to fetal invasiveness. Bioessays. 2012;34:26–35. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaitu'u-Lino TJ, Morison NB, Salamonsen LA. Estrogen is not essential for full endometrial restoration after breakdown: Lessons from a mouse model. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5105–5111. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudolph M, Döcke WD, Müller A, Menning A, Röse L, Zollner TM, Gashaw I. Induction of overt menstruation in intact mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maruyama T, Miyazaki K, Masuda H, Ono M, Uchida H, Yoshimura Y. Review: Human uterine stem/progenitor cells: Implications for uterine physiology and pathology. Placenta. 2013;34(Suppl):S68–S72. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li YF, Xu XB, Chen XH, Wei G, He B, Wang JD. The nuclear factor-κB pathway is involved in matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in RU486-induced endometrium breakdown in mice. Human Reproduction. 2012;27:2096–2106. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu B, Chen X, He B, Liu S, Li Y, Wang Q, Gao H, Wang S, Liu J, Zhang S, et al. ROS are critical for endometrial breakdown via NF-kappaB-COX-2 signaling in a female mouse menstrual-like model. Endocrinology. 2014;155:3638–3648. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen M, Meisser A, Bischof P. Metalloproteinases and human placental invasiveness. Placenta. 2006;27:783–793. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garry R, Hart R, Karthigasu KA, Burke C. A re-appraisal of the morphological changes within the endometrium during menstruation: A hysteroscopic, histological and scanning electron microscopic study. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:1393–1401. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jabbour HN, Kelly RW, Fraser HM, Critchley HO. Endocrine regulation of menstruation. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:17–46. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Q, Xu X, He B, Li Y, Chen X, Wang J. A critical period of progesterone withdrawal precedes endometrial breakdown and shedding in mouse menstrual-like model. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:1670–1678. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly RW, King AE, Critchley HO. Cytokine control in human endometrium. Reproduction. 2001;121:3–19. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu X, Guan S, He B, Wang J. Active role of the predecidual-like zone in endometrial shedding in a mouse menstrual-like model. Eur J Histochem. 2013;57:e25. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2013.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen X, Liu J, He B, Li Y, Liu S, Wu B, Wang S, Zhang S, Xu X, Wang J. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) regulation by hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF1A) starts and peaks during endometrial breakdown, not repair, in a mouse menstrual-like model. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:2160–2170. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X, Wu B, Wang S, Liu J, Gao H, Zhou F, Nan N, Zhang B, Wang J, Xu X, He B. Hypoxia: Involved but not essential for endometrial breakdown in mouse menstural-like model. Reproduction. 2020;159:133–144. doi: 10.1530/REP-18-0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salamonsen LA. Tissue injury and repair in the female human reproductive tract. Reproduction. 2003;125:301–311. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1250301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jemma E. Extracellular matrix dynamics in scar-free endometrial repair: Perspectives from mouse in vivo and human in vitro studies. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:511–523. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.090993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferenczy A. Studies on the cytodynamics of human endometrial regeneration. II. Transmission electron microscopy and histochemistry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;124:582–595. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patterson AL, Zhang L, Arango NA, Teixeira J, Pru JK. Mesenchymal-To-Epithelial transition contributes to endometrial regeneration following natural and artificial decidualization. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:964–974. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang LE, Gu J, Schau M, Bunn HF. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is mediated by an O2-dependent degradation domain via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7987–7992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maybin JA, Murray AA, Saunders PT, Hirani N, Carmeliet P, Critchley HO. Hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha are required for normal endometrial repair during menstruation. Nat Commun. 2018;9:295. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02375-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cousins FL, Murray AA, Scanlon JP, Saunders PT. Hypoxyprobe reveals dynamic spatial and temporal changes in hypoxia in a mouse model of endometrial breakdown and repair. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:30. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1842-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coudyzer P, Lemoine P, Jordan BF, Gallez B, Galant C, Nisolle M, Courtoy PJ, Henriet P, Marbaix E. Hypoxia is not required for human endometrial breakdown or repair in a xenograft model of menstruation. FASEB J. 2013;27:3711–3719. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-232074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaitu'u-Lino TJ, Morison NB, Salamonsen LA. Neutrophil depletion retards endometrial repair in a mouse model. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;328:197–206. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Menning A, Walter A, Rudolph M, Gashaw I, Fritzemeier KH, Roese L. Granulocytes and vascularization regulate uterine bleeding and tissue remodeling in a mouse menstruation model. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Critchley HO, Kelly RW, Brenner RM, Baird DT. Antiprogestins as a model for progesterone withdrawal. Steroids. 2003;68:10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salamonsen LA, Woolley DE. Menstruation: Induction by matrix metalloproteinases and inflammatory cells. J Reprod Immunol. 1999;44:1–27. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0378(99)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Curry TE, Jr, Osteen KG. The matrix metalloproteinase system: Changes, regulation, and impact throughout the ovarian and uterine reproductive cycle. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:428–465. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaitu'u TJ, Shen J, Zhang J, Morison NB, Salamonsen LA. Matrix metalloproteinases in endometrial breakdown and repair: Functional significance in a mouse model. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:672–680. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.042473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cousins FL, Kirkwood PM, Murray AA, Collins F, Gibson DA, Saunders PT. Androgens regulate scarless repair of the endometrial ‘Wound’ in a mouse model of menstruation. FASEB J. 2016;30:2802–2811. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600078R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryan SA. The treatment of dysmenorrhea. Pediatric Clin North America. 2017;64:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trundley A, Moffett A. Human uterine leukocytes and pregnancy. Tissue Antigens. 2004;63:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andersch B, Milsom I. An epidemiologic study of young women with dysmenorrhea. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;15:655–660. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang L, Cao Z, Yu B, Chai C. An in vivo mouse model of primary dysmenorrhea. Exp Anim. 2015;64:295–303. doi: 10.1538/expanim.14-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitchell JA, Yochim JM. Intrauterine oxygen tension during the estrous cycle in the rat: Its relation to uterine respiration and vascular activity. Endocrinology. 1968;83:701–705. doi: 10.1210/endo-83-4-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wankell M, Munz B, Hübner G, Hans W, Wolf E, Goppelt A, Werner S. Impaired wound healing in transgenic mice overexpressing the activin antagonist follistatin in the epidermis. EMBO J. 2001;20:5361–5372. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finn CA. Implantation, menstruation and inflammation. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 1986;61:313–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1986.tb00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nathirojanakun P, Taneepanichskul S, Sappakitkumjorn N. Efficacy of a selective COX-2 inhibitor for controlling irregular uterine bleeding in DMPA users. Contraception. 2006;73:584–587. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu X, Chen X, Li Y, Cao H, Shi C, Guan S, Zhang S, He B, Wang J. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulated by the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway plays an important role in endometrial breakdown in a female mouse menstrual-like model. Endocrinology. 2013;154:2900–2911. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heard ME, Velarde MC, Giudice LC, Simmen FA, Simmen RC. Kruppel-Like factor 13 deficiency in uterine endometrial cells contributes to defective steroid hormone receptor signaling but not lesion establishment in a mouse model of endometriosis. Biol Reprod. 2015;92:140. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.130260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstetrics Gynecol. 1927;14:93–94. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(15)30003-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pluchino N, Mamillapalli R, Moridi I, Tal R, Taylor HS. G-protein-coupled receptor CXCR7 is overexpressed in human and murine endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2018;25:1168–1174. doi: 10.1177/1933719118766256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Langendonckt A, Casanas-Roux F, Eggermont J, Donnez J. Characterization of iron deposition in endometriotic lesions induced in the nude mouse model. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1265–1271. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Defrere S, Van Langendonckt A, Vaesen S, Jouret M, Ramos RG, Gonzalez D, Donnez J. Iron overload enhances epithelial cell proliferation in endometriotic lesions induced in a murine model. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2810–2816. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mascarenhas MN, Flaxman SR, Boerma T, Vanderpoel S, Stevens GA. National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: A systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang Q, Zhang X, Shi Y, He YP, Sun ZS, Shi HJ, Wang J. Increased expression of NDRG3 in mouse uterus during embryo implantation and in mouse endometrial stromal cells during in vitro decidualization. Reprod Sci. 2018;25:1197–1207. doi: 10.1177/1933719117737843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Damjanov I. Decidua and implantation of the embryo from a historical perspective. Int J Dev Biol. 2014;58:75–78. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.140075id. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Clercq K, Hennes A, Vriens J. Isolation of mouse endometrial epithelial and stromal cells for in vitro decidualization. J Vis Exp. 2017;2:55168. doi: 10.3791/55168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lessey BA. The role of the endometrium during embryo implantation. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang S, Lin H, Kong S, Wang S, Wang H, Wang H, Armant DR. Physiological and molecular determinants of embryo implantation. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:939–980. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brosens JJ, Salker MS, Teklenburg G, Nautiyal J, Salter S, Lucas ES, Steel JH, Christian M, Chan YW, Boomsma CM, et al. Uterine selection of human embryos at implantation. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3894. doi: 10.1038/srep03894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang Y, Zhang D, Qin H, Liu S, Yan Q. PoFUT1 promotes endometrial decidualization by enhancing the O-fucosylation of notch1. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma HL, Gong F, Tang Y, Li X, Li X, Yang X, Lu G. Inhibition of endometrial tiam1/rac1 signals induced by miR-22 up-regulation leads to the failure of embryo implantation during the implantation window in pregnant mice. Biol Reprod. 2015;92:152. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.128603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sarsmaz K, Goker A, Micili SC, Ergur BU, Kuscu NK. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis of the effect of omega-3 on embryonic implantation in an experimental mouse model. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;55:351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schander JA, Correa F, Bariani MV, Blanco J, Cymeryng C, Jensen F, Wolfson ML, Franchi AM. A role for the endocannabinoid system in premature luteal regression and progesterone withdrawal in lipopolysaccharide-induced early pregnancy loss model. Mol Hum Reprod. 2016;22:800–808. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaw050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alappat S, Zhang ZY, Chen YP. Msx homeobox gene family and craniofacial development. Cell Res. 2003;13:429–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bolnick AD, Bolnick JM, Kilburn BA, Stewart T, Oakes J, Rodriguez-Kovacs J, Kohan-Ghadr HR, Dai J, Diamond MP, Hirota Y, et al. Reduced homeobox protein MSX1 in human endometrial tissue is linked to infertility. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2042–2050. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dewar AD. Litter size and the duration of pregnancy in mice. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1968;53:155–161. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1968.sp001954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Catalini L, Fedder J. Characteristics of the endometrium in menstruating species: Lessons learned from the animal kingdomdagger. Biol Reprod. 2020;26:1160–1169. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.