Abstract

Pelvic organ prolapses (POP) notably reduces the quality of life in elderly populations due to bladder and bowel dysfunction, incontinence, and coital problems. Extracellular matrix (ECM) disorder is a pivotal event in the progression of POP, but to date, its specific underlying mechanism remains unclear. The ligaments of patients with POP and healthy controls were collected to compare the expression of Homeobox11 (HOXA11) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β1) via immunohistochemical analysis. HOXA11 and TGF-β1 were overexpressed or knocked down in fibroblast cells to explore their effects on the expression of collagen and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). HOXA11 and TGF-β1 were greatly reduced in the ligaments of patients with POP. The overexpression and downregulation of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 can mediate ECM disorder via regulating expression of collagen (Col) and MMPs. In addition, HOXA11 and TGF-β1 exerted synergistic effect on the expression of Col and MMPs. The present study identified that HOXA11 and TGF-β1 serve critical roles in mediating ECM disorders, which may be of clinical significance for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with POP.

Keywords: pelvic organ prolapses, extracellular matrix, HOXA11, TGF-β1, expression

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common and persistent gynecological benign disease among the elderly female population, which reduced quality of life and sexual well-being of those affected (1). Currently, surgery remains the most common treatment for patients with severe POP (2). However, the risk of reoperation remains relatively high (~29.2%) due to increased recurrence (3,4). Several factors, including but not limited to chronic constipation, vaginal birth, chronic cough, obesity and hormones, have been recognized for their involvement in the development of POP (1,5). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying their development remain to be elucidated. Thus, further studies are required to investigate the progression of POP.

Recent studies have focused on the abnormal structure and organization of pelvic floor connective tissue, and the molecular alterations in uterosacral ligaments (USLs) (6–8). Notably, the breakdown of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is commonly reported (9,10). This process has been demonstrated to attenuate the strength of supportive structures and contribute to the pathogenesis of POP (11,12). However, the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the breakdown of the ECM are not yet fully understood.

Collagen (Col) is an important component of the ECM that supports the stability and plasticity of the pelvic floor. Col-I predominantly forms the coarse fibers and provides mechanical tension of the tissue (13). By contrast, Col-III forms the fine fibers to improve organ flexibility (13). Col is synthesized and secreted by fibroblasts in pelvic connective tissue (14). Col can be degraded by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), including MMP-2 and MMP-9 (15). However, tissue metalloproteinase inhibitors (TIMPs), including TIMP1 endogenously inhibit MMPs, inducing degradation of the ECM (16).

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is a multifunctional cytokine that affects several functions at the cellular and biological level, including immune regulation, embryo development, tumorigenesis, injury repair, cell proliferation, differentiation and migration, and ECM deposition (17). Homeobox11 (HOXA11) is a transcriptional regulator that has been reported to maintain the plasticity of the uterus during the menstrual cycle and in pregnancy (18,19). Connell et al (20) demonstrated that HOXA11 is involved in the development and maintenance of USLs, and is deficient in POP. However, whether HOXA11 is involved in the development of USLs remains to be elucidated.

Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the expression levels of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 in the USLs of women with and without POP. In addition, the effects of knockdown and overexpression of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 were investigated in cultured L929 fibroblasts to determine their association with Col and MMPs.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 10 USLs of patients with POP and 6 USLs without (40–60 years old) POP were collected between April 2019 and December 2019 at the Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (Wuhan, China). Written informed consent was provided by all patients prior to the commencement of the study. The present study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (approval no. 2018017). A pelvic examination was performed to evaluate for the presence of POP. Women with stage II POP or higher were assigned to the POP group. Women presenting the following criteria were excluded from the study: i) connective tissue diseases or collagen depleted-associated diseases; ii) pathologically confirmed endometriosis, or estrogen-associated ovarian tumors; or iii) undergoing surgery in the uterosacral ligamental site or a history of estrogen application within the previous three months.

Tissue collection and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tissues were obtained from 6 non-POP patients, who underwent USLs resection surgery excluding the presence of POP, and 10 patients with POP who underwent hysterectomy. USLs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 h at room temperature. Paraffin-embedded USLs were cut into 4-µm-thick sections. Briefly, the tissue sections were blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide solution and 5% BSA (cat. no. A8010; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 20 min at room temperature. The sections were incubated with rabbit polyclonal primary antibodies against HOXA11 (1:200 dilution; cat. no. NBP1-83233; Novus Biologicals, Ltd.) and TGF-β1 (1:100 dilution; cat. no. ab92486; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with a polyclonal goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) at 37°C for 2 h. DAB solution was used for staining for 5 min at room temperature and the tissue sections were subsequently counterstained with hematoxylin for 1 min at room temperature. The stained slides were assessed by two pathologists independent of the present study under a light microscope (magnification, ×400; Zeiss AG). A total of 5 fields of view were selected from uniformly dyed areas of the tissue sections.

Cell transfection

The L929 murine fibroblast cell line was purchased from The National Centre for Cell Science. Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Hyclone; Cytiva) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were seeded (1×106 cells/well) into 6-well plates and transfected with 75 pmol small interfering (si) RNA (HOXA11 or TGF-β1), siRNA-negative control (NC) or plasmid vectors (all purchased from Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology) using Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Plasmid vectors were extracted using the endotoxin-free plasmid extraction kit (cat. no. DP117; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.). Cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 were used as the negative control. Subsequent experimentation was performed 48 h post-transfection.

The HOXA11-targeting siRNA expression system included the following sequences: siRNA-NC, 5′-GCCAAACTCTCTGTTGGTT-3′; siRNA-1, 5′-GCCTGAAACTCTCTTGGTT-3′; siRNA-2, 5′-GGGTGTGGTCACTGGAGAT-3′; and siRNA-3, 5′-CCATCTCAGAGCTGACTAT-3′. The TGF-β1-targeting siRNA expression system included the following sequences: siRNA-NC, 5′-GCAACAATTCCTGGCGTTA-3′; siRNA-1, 5′-GCAACAATTCCTGGCGTTA-3′; siRNA-2, 5′-GGAGAGCCCTGGATACCAA-3′; and siRNA-3, 5′-GGAAGGACCTGGGTTGGAA-3′.

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR

Total RNA was extracted from L929 cells (2×106) using TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using the M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase kit [cat. no. EQ002; ELK (Wuhan) Biotechnology Co., Ltd.]. The following temperature protocol was used for reverse transcription: 42°C for 50 min for the reverse transcription reaction; 99°C for 5 min to inactivate the reverse transcriptase; and 4°C to save the reverse transcription product. qPCR was subsequently performed using the SYBR-Green PCR SuperMix kit (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The thermocycling conditions used for qPCR were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The primers sequences used for qPCR are listed in Table I. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (21) and normalized to the internal reference gene GAPDH.

Table I.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR primers.

| Gene | Primer | Primer sequences | Annealing temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-TGAAGGGTGGAGCCAAAAG-3′ | 58.3 |

| Reverse | 5′-AGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGAT-3′ | 58.4 | |

| HOXA11 | Forward | 5′-CAATCTGGCCCACTGCTACTC-3′ | 59.7 |

| Reverse | 5′-GTGGGGTGGTGGTAGACGTT-3′ | 59.2 | |

| TGF-β1 | Forward | 5′-AGAGCCCTGGATACCAACTATTG-3′ | 59.5 |

| Reverse | 5′-TGCGACCCACGTAGTAGACG-3′ | 59.4 | |

| COL1A1 | Forward | 5′-CTGACTGGAAGAGCGGAGAG-3′ | 57.2 |

| Reverse | 5′-CGGCTGAGTAGGGAACACAC-3′ | 57.8 | |

| COL3A1 | Forward | 5′-CTCAAGAGTGGAGAATACTGGGTT-3′ | 58.8 |

| Reverse | 5′-CTCAAGAGTGGAGAATACTGGGTT-3′ | 58.1 | |

| MMP-2 | Forward | 5′-GAATGCCATCCCTGATAACCT-3′ | 58.2 |

| Reverse | 5′-GCTTCCAAACTTCACGCTCTT-3′ | 59 | |

| MMP-9 | Forward | 5′-AAGGGTACAGCCTGTTCCTGGT-3′ | 61.7 |

| Reverse | 5′-CTGGATGCCGTCTATGTCGTCT-3′ | 61.6 | |

| TIMP1 | Forward | 5′-CCAGAAATCATCGAGACCACC-3′ | 59.2 |

| Reverse | 5′-ATTTCCGTTCCTTAAACGGC-3′ | 58.8 |

COL1A1, collagen α1(I) chain; COL3A1, collagen α1(III) chain; HOXA11, Homeobox11; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; TIMP1, tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor 1.

Western blotting

Cells were washed three times with pre-cooled PBS, seeded into 6-well plates and collected via scraping. Total protein was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with 1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), and quantified using the bicinchoninic acid assay kit (cat. no. AS1086; Wuhan Aspen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Equal amounts of protein (40 µg per lane) were separated ovia 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, which were blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against Col-I (1:300 dilution; cat. ab34710; Abcam), Col-III (1:200 dilution; cat. ab23445; Abcam), HOXA11 (1:200 dilution; cat. no. NBP1-83233; Novus Biologicals, Ltd.), TGF-β1 (1:100 dilution; cat. no. ab92486; Abcam), MMP-2 (1:300 dilution; cat. no. ab97779; Abcam), MMP-9 (1:300 dilution; cat. no. ab38898; Abcam) and TIMP1 (1:300 dilution; cat. no. ab12684; Abcam), overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed three times with PBS-0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) for 10 min each time. Following the primary incubation, membranes were incubated with a polyclonal goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using the Developer and Fixed kit (cat. no. P0020; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and analyzed using Odyssey infrared laser scanning imaging (LI-COR Biosciences). Protein expression was semi-quantified using ImageJ software (version 6.0; National Institutes of Health) with GAPDH as the loading control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 6; GraphPad Software, Inc.). All experiments were performed in triplicate and data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Student's independent t-test was used to compare two groups, multiple groups were statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Molecular expression in POP tissues

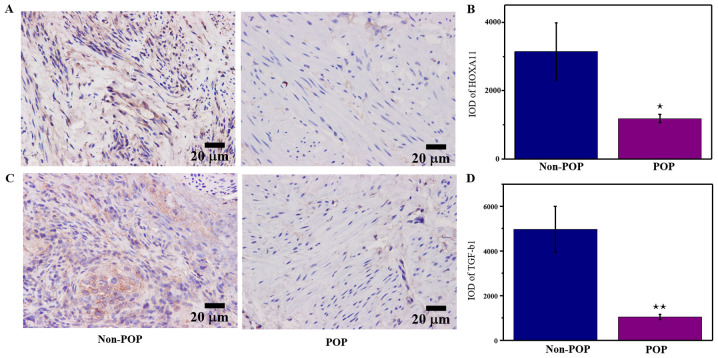

IHC was performed to determine whether HOXA11 and TGF-β1 were differentially expressed between POP tissues and normal tissues. The results demonstrated that HOXA11 and TGF-β1 levels were significantly lower in patients with POP compared with those without POP (Fig. 1). These results suggested that downregulation of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 expression may be involved in the development of POP.

Figure 1.

Molecular expression in POP tissues. Immunohistochemical analysis of (A) HOXA11 and (C) TGF-β1 in POP and non-POP tissues. Semi-quantitative analysis of (B) HOXA11 and (D) TGF-β1. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. non-POP. HOXA11, Homeobox11; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β; POP, pelvic organ prolapses; IOD, integrated optical density.

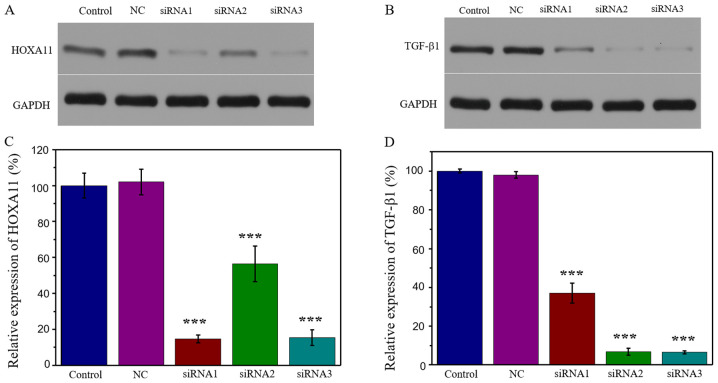

Knockdown of HOXA11 and TGF-β1

HOXA11 is a key structural component of pelvic organs and an essential gene for the development of USLs (20,22). TGF-β1 is a multifunctional cytokine that serves a key role in ECM metabolism. TGF-β1 expression is reported to be downregulated in women with stress urinary incontinence and its expression is negatively associated with POP (23,24). In order to determine whether HOXA11 and TGF-β1 influenced ECM expression, and the combined effect of the two on ECM expression, the present study successfully established HOXA11 and TGF-β1 knockdown models. The results demonstrated that transfection with HOXA11-siRNA1 exhibited the strongest suppression efficiency, whereby HOXA11 protein expression was 14.70% (Fig. 2A and C). Similarly, transfection with TGF-β1-siRNA3 exhibited the strongest suppression efficiency (6.55%; Fig. 2B and D). Thus, HOXA11-siRNA1 and TGF-β1-siRNA3 were selected for further experimentation.

Figure 2.

HOXA11 and TGF-β1 knockdown. Expression of (A) HOXA11 and (B) TGF-β1 following siRNA transfection. Semi-quantitative analysis of (C) HOXA11-siRNAs and (D) TGF-β1-siRNAs. ***P<0.001 vs. NC. HOXA11, Homeobox11; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control.

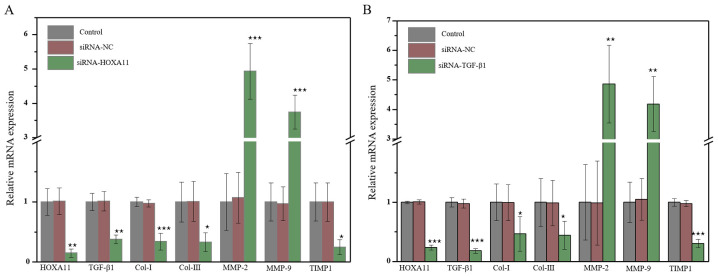

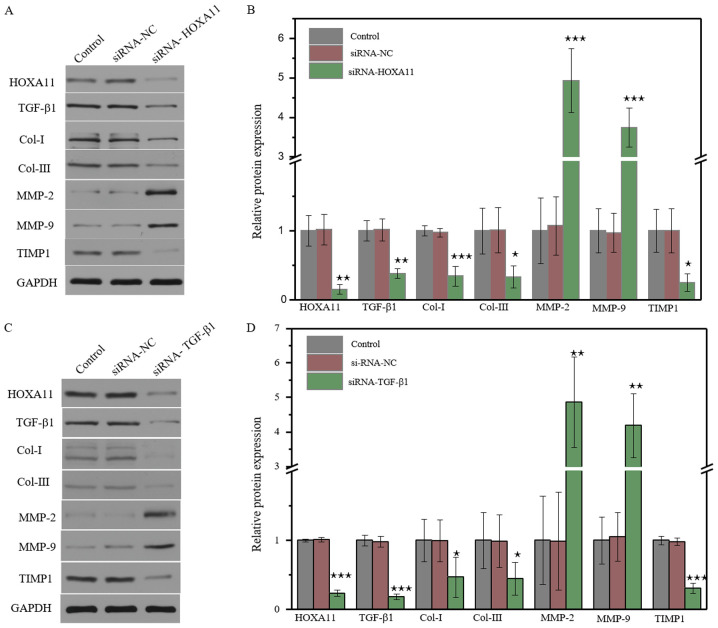

Col and MMP expression are altered when HOXA11 and TGF-β1 are downregulated

HOXA11 mRNA expression was significantly downregulated in L929 cells transfected with HOXA11-siRNA1. In addition, mRNA expression levels of Col-I, Col-III and TIMP1 significantly decreased, whereas the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 significantly increased (Fig. 3A). Transfection with TGF-β1-siRNA3 exhibited the same effects as transfection with HOXA11-siRNA1 (Fig. 3B). The protein expression levels of Cols and MMPs were further investigated. The results demonstrated that the knockdown of HOXA11 could suppress Col-I, Col-III and TIMP1 expression, and elevate MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression (Fig. 4A). Transfection with TGF-β1-siRNA had the same effect as HOXA11 knockdown (Fig. 4B). In addition, HOXA11 knockdown could inhibit TGF-β1 expression, and TGF-β1 could alter HOXA11 expression. Taken together, these results suggested that HOXA11 and TGF-β1 exert mutual functions.

Figure 3.

The molecular mRNA expression when HOXA11 or TGF-β1 knocked down. mRNA expression of Col-I, Col-III, HOXA11, TGF-β1, MMP-2, MMP-9 and TIMP1 in (A) HOXA11-siRNA group and (B) TGF-β1-siRNA group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. siRNA-NC. Col, collagen; HOXA11, Homeobox11; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; TIMP1, tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor 1; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control.

Figure 4.

Molecular protein expression levels following HOXA11 or TGF-β1 knockdown. The protein expression of Col-I, Col-III, HOXA11, TGF-β1, MMP-2, MMP-9 and TIMP1 in the (A) HOXA11-siRNA group and (C) TGF-β1-siRNA group. Semi-quantitative analysis of protein expression in (B) HOXA11-siRNA group and (D) TGF-β1-siRNA group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. NC. Col, collagen; HOXA11, Homeobox11; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; TIMP1, tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor 1; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control

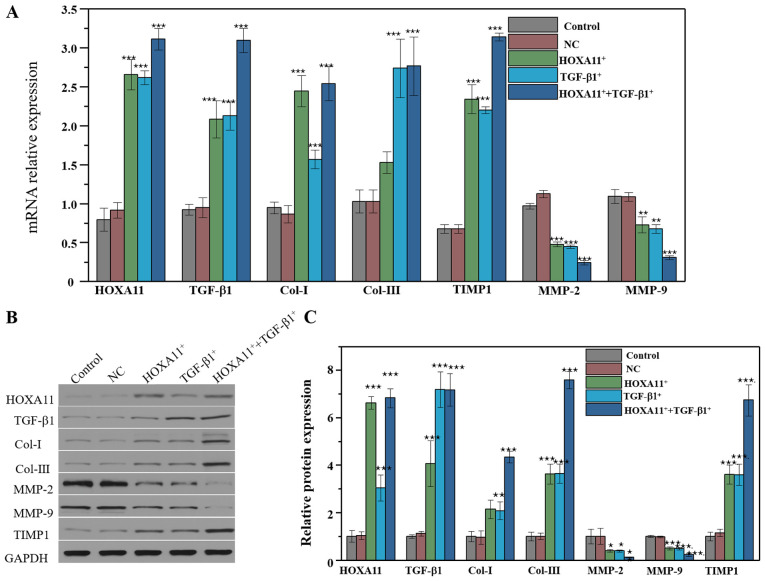

Col and MMP expression following overexpression of HOXA11 and TGF-β1

L929 cells were transfected with HOXA11 and TGF-β1 overexpression plasmids to verify their effects on the expression of Col and MMPs. As expected, HOXA11 and TGF-β1 mRNA expression levels significantly increased in cells transfected with HOXA11 and TGF-β1 vectors. In addition, the mRNA expression levels of Col-I, Col-III and TIMP1 markedly increased, whereas the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 significantly decreased. Col and MMPs expression levels were notably higher in the co-overexpression group compared with the single overexpression group (Fig. 5A). In addition, HOXA11 and TGF-β1 possessed a synergistic effect on the expression of Col and MMPs. The effect of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 on Cols and MMPs were further assessed at the protein level (Fig. 5B and C). The results demonstrated that HOXA11 and TGF-β1 expression significantly increased following transfection with HOXA11 and TGF-β1 mimics. Notably, the mRNA expression levels of Col-I, Col-III and TIMP1 significantly increased, whereas the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 decreased following co-overexpression.

Figure 5.

Molecular protein expression levels following HOXA11 or TGF-β1 overexpression. (A) mRNA expression of Col-I, Col-III, HOXA11, TGF-β1, MMP-2, MMP-9 and TIMP1 in HOXA11 and TGF-β1 overexpression groups. (B) Protein expression and (C) the semi-quantitative analysis of Col-I, Col-III, HOXA11, TGF-β1, MMP-2, MMP-9 and TIMP1 in HOXA11 and TGF-β1 overexpression groups. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. NC. Col, collagen; HOXA11, Homeobox11; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; TIMP1, tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor 1; NC, negative control.

Discussion

POP is a prevalent reproductive disease among menopausal women, which causes a major medical and financial burden due to the bladder and bowel dysfunction, incontinence and coital problems (25,26). Several factors such as vaginal birth, forceps delivery, obesity and aging are considered high risk factors of POP (1,27). However, the underlying pathophysiology mechanism of POP remains to be elucidated.

Increasing evidence suggests that alterations to the connective tissue induce structural damage to the pelvic floor (28,29). The balance between the synthesis and degradation of Cols, including Col-I and Col-III, is considered the basis for the continuous remodeling of ECM (26). The degradation of Col is predominantly mediated by MMPs, while Col synthesis is regulated by TIMPs (30). Previous studies have demonstrated that the levels of Col-I and Col-III are downregulated in POP tissues (31,32). However, the molecular mechanism underlying downregulation of Col in POP remains to be elucidated.

HOXA11 is a transcription factor that regulates female fertility (33). HOXA11 expression is enhanced during the development of the human reproductive tract, and is critical for the development of ligaments (34). TGF-β1 has been reported to regulate cellular proliferation, differentiation, and ECM deposition (35). However, another study indicated that TGF-β1 expression is decreased in the vaginal wall of women with POP (24). The molecular mechanism of TGF-β1 remains unclear. The results of the present study demonstrated that the expression levels of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 were significantly downregulated in the USLs of patients with POP, which was consistent with previous studies (20,36). In addition, HOXA11 expression was indicated to influence TGF-β1 expression, and vice versa.

L929 murine fibroblasts have been extensively used to assess the ECM (37). In order to further investigate the function of HOXA11 and TGF-β1, the expression levels of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 were knocked down. Notably, downregulation of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 significantly decreased ECM expression. Overexpression of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 in L929 cells confirmed that they can promote the synthesis of Col while suppressing its degradation. In addition, co-overexpression of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 markedly increased the expression levels of Col-I and Col-III and inhibited the levels of MMPs. Collectively, these results suggested that HOXA11 and TGF-β1 exerted a synergistic effect on the expression of Cols, something that has rarely been reported in previous studies. As expected, overexpression of HOXA11 promoted TGF-β1 expression and overexpression of TGF-β1 similarly enhanced HOXA11 expression. A previous study reported that HOXA11 regulates the development and progression of non-small cell lung cancer via the TGF-β1 signaling pathway (38). However, the association between HOXA11 and TGF-β1 requires further study and the relationship between HOXA11, TGF-β1 and clinicopathological grading of patients with POP should be further investigated.

Overall, the results of the present study demonstrated that the expression levels of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 were downregulated in the USLs of patients with POP compared with those without POP. In addition, HOXA11 and TGF-β1 were indicated to mediate POP by regulating the expression levels of Cols and MMPs. The results demonstrated that HOXA11 and TGF-β1 exerted a synergistic effect on the expression levels of Cols and MMPs. In addition, HOXA11 downregulated TGF-β1 expression, and vice versa. Together, the results of the present study confirmed that the reduction of ECM caused by the loss of HOXA11 and TGF-β1 is a critical factor in the occurrence of POP. The present study may aid our understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms and the development of POP, and provide novel insights into the effective diagnosis and targeted therapy of patients with POP.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- POP

pelvic organ prolapses

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- USLs

uterosacral ligaments

- Col

collagen

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- TIMPs

tissue metalloproteinase inhibitors

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

- HOXA11

Homeobox11

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

Funding

This study was supported by the Independent scientific research project of Wuhan University (grant no. 413000117), the Chinese Medical Association Clinical Research Fund-Reproductive Medicine Young Physicians Research and Development Project (grant no. 17020310700) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China NSFC (grant no. 81860276).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

LZ, FD, YC and XY conceived and designed the study. LZ, FD, SX, YZ, ZD and LZ conducted the experiment. YW, MY, DY, SL and GC analyzed the data and prepared the diagrams. LZ and GC drafted the manuscript and FD revised the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (approval no. 2018017). Written informed consent was provided by all patients prior to the commencement of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Vergeldt TF, Weemhoff M, IntHout J, Kluivers KB. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse and its recurrence: A systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1559–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2695-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman D, Zetterstrom J, Schultz I, Nordenstam J, Hjern F, Lopez A, Mellgren A. Pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence in women with surgically managed rectal prolapse: A population-based case-control study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:28–35. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark AL, Gregory T, Smith VJ, Edwards R. Epidemiologic evaluation of reoperation for surgically treated pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1261–1267. doi: 10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00829-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delancey JO, Kane Low L, Miller JM, Patel DA, Tumbarello JA. Graphic integration of causal factors of pelvic floor disorders: An integrated life span model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:610.e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao X, Ma C, Li R, Xue J, Liu L, Liu P. Hypoxia induces apoptosis through HIF-1α signaling pathway in human uterosacral ligaments of pelvic organ prolapse. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8316094. doi: 10.1155/2017/8316094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun MJ, Cheng YS, Liu CS, Sun R. Changes in the PGC-1α and mtDNA copy number may play a role in the development of pelvic organ prolapse in pre-menopausal patients. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;58:526–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2019.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Zheng P, Duan A, Hao Y, Lu C, Lu D. [Corrigendum] Genomewide DNA methylation analysis of uterosacral ligaments in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19:2458. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.9852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyagi T, Alarab M, Leong Y, Lye S, Shynlova O. Local oestrogen therapy modulates extracellular matrix and immune response in the vaginal tissue of post-menopausal women with severe pelvic organ prolapse. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:2907–2919. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alarab M, Kufaishi H, Lye S, Drutz H, Shynlova O. Expression of extracellular matrix-remodeling proteins is altered in vaginal tissue of premenopausal women with severe pelvic organ prolapse. Reprod Sci. 2014;21:704–715. doi: 10.1177/1933719113512529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Landsheere L, Blacher S, Munaut C, Nusgens B, Rubod C, Noel A, Foidart JM, Cosson M, Nisolle M. Changes in elastin density in different locations of the vaginal wall in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:1673–1681. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strinic T, Vulic M, Tomic S, Capkun V, Stipic I, Alujevic I. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in uterosacral ligament tissue from women with pelvic organ prolapse. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:832–834. doi: 10.3109/00016341003592545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budatha M, Roshanravan S, Zheng Q, Weislander C, Chapman SL, Davis EC, Starcher B, Word RA, Yanagisawa H. Extracellular matrix proteases contribute to progression of pelvic organ prolapse in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2048–2059. doi: 10.1172/JCI45636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodley DT, Krueger GG, Jorgensen CM, Fairley JA, Atha T, Huang Y, Chan L, Keene DR, Chen M. Normal and gene-corrected dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa fibroblasts alone can produce type VII collagen at the basement membrane zone. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1021–1028. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piperi C, Papavassiliou AG. Molecular mechanisms regulating matrix metalloproteinases. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012;12:1095–1112. doi: 10.2174/1568026611208011095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai W, Liang Z, Liu H, Zhao G, Ju C. Lunasin abrogates the expression of matrix metalloproteinases and reduction of type II collagen. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47:3259–3264. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1623227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun B, Zhou L, Wen Y, Wang C, Baer TM, Pera RR, Chen B. Proliferative behavior of vaginal fibroblasts from women with pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;183:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor HS, Vanden Heuvel GB, Igarashi P. A conserved Hox axis in the mouse and human female reproductive system: Late establishment and persistent adult expression of the Hoxa cluster genes. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:1338–1345. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.6.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor HS, Igarashi P, Olive DL, Arici A. Sex steroids mediate HOXA11 expression in the human peri-implantation endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1129–1135. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.3.5573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connell KA, Guess MK, Chen H, Andikyan V, Bercik R, Taylor HS. HOXA11 is critical for development and maintenance of uterosacral ligaments and deficient in pelvic prolapse. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1050–1055. doi: 10.1172/JCI34193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma Y, Guess M, Datar A, Hennessey A, Cardenas I, Johnson J, Connell KA. Knockdown of Hoxa11 in vivo in the uterosacral ligament and uterus of mice results in altered collagen and matrix metalloproteinase activity. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:100. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.093245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen Y, Polan ML, Chen B. Do extracellular matrix protein expressions change with cyclic reproductive hormones in pelvic connective tissue from women with stress urinary incontinence? Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1266–1273. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meijerink AM, van Rijssel RH, van der Linden PJ. Tissue composition of the vaginal wall in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2013;75:21–27. doi: 10.1159/000341709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emmerson S, Mukherjee S, Melendez-Munoz J, Cousins F, Edwards SL, Karjalainen P, Ng M, Tan KS, Darzi S, Bhakoo K, et al. Composite mesh design for delivery of autologous mesenchymal stem cells influences mesh integration, exposure and biocompatibility in an ovine model of pelvic organ prolapse. Biomaterials. 2019;225:119495. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elneil S. Complex pelvic floor failure and associated problems. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:555–573. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee UJ, Kerkhof MH, van Leijsen SA, Heesakkers JP. Obesity and pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol. 2017;27:428–434. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu J, Qin M, Fan B, Chen X. Klotho protein reduced the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) and matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3) in fibroblasts from patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) by Down-regulating the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:3815–3824. doi: 10.12659/MSM.913623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng C, Liu J, Wang H, Zhou Y, Wu J, Yan G. Correlation between autophagy and collagen deposition in patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:213–221. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lachowski D, Cortes E, Rice A, Pinato D, Rombouts K, Del Rio Hernandez A. Matrix stiffness modulates the activity of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in hepatic stellate cells to perpetuate fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7299. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43759-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dökmeci F, Tekşen F, Çetinkaya ŞE, Özkan T, Kaplan F, Köse K. Expressions of homeobox, collagen and estrogen genes in women with uterine prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S, Lu D, Zhang Z, Jia X, Yang L. Effects of mechanical stretching on the morphology of extracellular polymers and the mRNA expression of collagens and small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycans in vaginal fibroblasts from women with pelvic organ prolapse. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makker A, Goel MM, Nigam D, Bhatia V, Mahdi AA, Das V, Pandey A. Endometrial expression of homeobox genes and cell adhesion molecules in infertile women with intramural fibroids during window of implantation. Reprod Sci. 2017;24:435–444. doi: 10.1177/1933719116657196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunha GR, Robboy SJ, Kurita T, Isaacson D, Shen J, Cao M, Baskin LS. Development of the human female reproductive tract. Differentiation. 2018;103:46–65. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nigdelioglu R, Hamanaka RB, Meliton AY, O'Leary E, Witt LJ, Cho T, Sun K, Bonham C, Wu D, Woods PS, et al. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β promotes de novo serine synthesis for collagen production. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:27239–27251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.756247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leegant A, Zuckerwise LC, Downing K, Brouwer-Visser J, Zhu C, Cossio MJ, Strube F, Xie X, Banks E, Huang GS. Transforming growth factor β1 and extracellular matrix protease expression in the uterosacral ligaments of patients with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:53–58. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ventura RD, Padalhin AR, Park CM, Lee BT. Enhanced decellularization technique of porcine dermal ECM for tissue engineering applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;104:109841. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, He RQ, Dang YW, Zhang XL, Wang X, Huang SN, Huang WT, Jiang MT, Gan XN, Xie Y, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the long noncoding RNA HOXA11-AS gene interaction regulatory network in NSCLC cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2016;16:89. doi: 10.1186/s12935-016-0366-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.