Abstract

Objective

We assessed changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of electronic health record (EHR) benefit before and after transition from a local basic to a commercial comprehensive EHR.

Methods

Changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit were captured via a survey of academic health care providers before (baseline) and at 6–12 months (short term) and 12–24 months (long term) after the transition. We analyzed 32 items for the overall group and by practice setting, provider age, and specialty using separate multivariable-adjusted random effects logistic regression models.

Results

A total of 223 providers completed all 3 surveys (30% response rate): 85.6% had outpatient practices, 56.5% were >45 years old, and 23.8% were primary care providers. The percentage of providers with positive perceptions significantly increased from baseline to long-term follow-up for patient communication, hospital transitions – access to clinical information, preventive care delivery, preventive care prompt, preventive lab prompt, satisfaction with system reliability, and sharing medical information (P < .05 for each). The percentage of providers with positive perceptions significantly decreased over time for overall satisfaction, productivity, better patient care, clinical decision quality, easy access to patient information, monitoring patients, more time for patients, coordination of care, computer access, adequate resources, and satisfaction with ease of use (P < 0.05 for each). Results varied by subgroup.

Conclusion

After a transition to a commercial comprehensive EHR, items with significant increases and significant decreases in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit were identified, overall and by subgroup.

Keywords: electronic health records, healthcare providers, comprehensive EHR, satisfaction, survey

INTRODUCTION

Electronic health records (EHRs) that capture extensive patient information have the potential to improve health care delivery and enhance patient safety.1,2 Federal incentive programs, such as the Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs for meaningful use, have encouraged EHR implementation in inpatient and outpatient settings to improve the safety, quality, and efficiency of patient care.3 Many health care organizations are phasing in implementation of a comprehensive EHR, which is defined as implementation of all functionality (ie, electronic clinical information, computerized provider order entry, results management, and decision support) in the majority of clinical units. This is in contrast to implementation of a basic EHR, which includes a smaller subset of functionality in only some clinical units.4 Implementation of basic and comprehensive EHRs has increased in recent years. In 2015, 96% of non-federal acute care hospitals in the United States reported having (but not necessarily implementing) EHR technology; 83.8% reported implementing a basic EHR and 40% reported implementing a comprehensive EHR.4

Given that comprehensive EHRs are designed to improve health care delivery and patient safety, it is important to understand whether providers perceive these benefits. Health care providers are the primary users of EHRs, and their perceptions of the benefits are important and could influence successful integration of EHRs into clinical practice.5 Potential factors contributing to poor perceptions regarding EHR benefits include dissatisfaction with and barriers to EHR use.6,7 It has been hypothesized that perceptions about the benefits of EHRs will improve with time as providers use the technology.8 However, few studies have assessed provider perceptions and satisfaction before, during, and after EHR implementation. Hanauer et al.8 recently reported that a 2-year prospective survey limited to physicians in 3 primary care departments at a single institution did not find evidence that positive perceptions about EHRs eventually exceeded baseline measures. Our study extends prior work, in that we explored perceptions over time among primary care and specialty physician and non-physician providers, and our study population included those practicing in outpatient and inpatient settings. The objectives of the current analyses were 2-fold: (1) to assess changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit from baseline to follow-up after transition from a local basic EHR to a commercial comprehensive EHR across an integrated multispecialty health care system and (2) to explore changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit by practice setting and by provider age and specialty for providers with outpatient practices.

METHODS

Study design and population: We conducted a longitudinal analysis of survey data from providers in a large, nonprofit, multispecialty academic health care system that acquired and integrated a comprehensive, commercially available EHR (EpicCare 2010, Madison, WI, USA) for inpatient and outpatient medical care. At the time of the study, the health care system included 8 hospitals and 38 clinics located in the urban and rural regions of southeastern Louisiana. Prior to implementing the commercial comprehensive EHR, the health care system used a local basic EHR (Ochsner Clinical Workstation, New Orleans, LA, USA) that was certified by the Certification Commission for Healthcare Information Technology, an Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology–authorized certification body. A comparison of local basic and commercial comprehensive EHR functions is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of local basic vs commercial comprehensive EHR functions

| EHR functions | Functions implemented in local basic EHR | Functions implemented in commercial comprehensive EHR |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic clinical information | ||

| Patient demographicsa,b | Yes | Yes |

| Physician notesa,b | Yes | Yes |

| Nursing assessmentsa,b | Limited | Yes |

| Problem listsa.b | Yes | Yes |

| Medication listsa,b | Yes | Yes |

| Discharge summariesa,b | Yes | Yes |

| Advance directivesb | Limited | Yes |

| Computerized provider order entry | ||

| Lab reportsb | Yes | Yes |

| Radiology testsb | Yes | Yes |

| Medicationsa | Yes | Yes |

| Consultation requestsb | Yes | Yes |

| Nursing ordersb | No | Yes |

| Results management | ||

| View lab reportsa,b | Yes | Yes |

| View radiology reportsa,b | Yes | Yes |

| View radiology imagesb | Yes | Yes |

| View diagnostic test resultsa,b | Yes | Yes |

| View diagnostic test imagesb | Yes | Yes |

| View consultant reportsb | Yes | Yes |

| Decision support | ||

| Clinical guidelinesb | No | Yes |

| Clinical remindersb | No | Yes |

| Drug allergy resultsb | Yes | Yes |

| Drug-drug interactionsb | Yes | Yes |

| Drug-lab interactionsb | No | No |

| Drug dosing supportb | No | Yes |

Prior to and during implementation of the commercial comprehensive EHR, all providers received training, supplemental information on system upgrades during the implementation phase, and engagement regarding streamlining workflows. Clinical groups developed customized content, including order sets and documentation templates.

The comprehensive commercial EHR was phased in from 2012–2013 (including both inpatient and outpatient components) throughout the health care system. During the implementation, the Epic team made minor enhancements to the system in response to provider feedback and requests. There was one major upgrade in May 2014 to increase the functionality of the standard set of tools (from Epic 2010 to Epic 2014), which occurred during the final follow-up, affecting 10.9% of the providers who participated in this study.

Providers (n = 743) were eligible for this study if they were physicians (MD or DO), nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or optometrists; employed for the duration of the study period (baseline assessment through long-term follow-up, beginning first quarter 2011 up to first quarter 2015); had at least 1 year of work experience within the health care system prior to the transition; were using the EHR system on average at least once per week for patient care; and were not trainees. Participating providers completed baseline surveys in 2011 prior to the go-live dates of the commercial comprehensive EHR. These providers were resurveyed at 6–12 months (short-term follow-up) and then 12–24 months (long-term follow-up) after implementation of the EHR at their site.

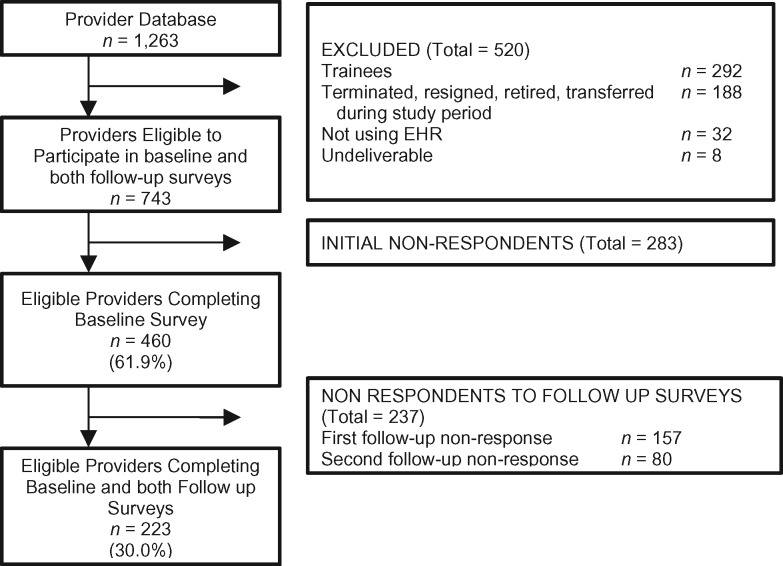

Using the tailored design survey method principles,9 we initially contacted providers by e-mail with a link to the online survey; non-responders were sent weekly reminder e-mails for approximately 8 weeks. Then, persistent non-responders were contacted by mail with a hard-copy survey to complete and return in a self-addressed, stamped envelope, followed by final e-mail reminders. Providers were incentivized to participate with a raffle for a free iPad for each phase of the survey. In addition, those who received the survey by mail were given a flash drive and/or a pen in appreciation of their time completing the survey. Only providers who had completed both the baseline and the 2 follow-up surveys were eligible for the final analyses (Figure 1). The study was determined to be exempt by the Ochsner Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Study design and participant completion rate.

Survey description

The survey captured demographic and practice characteristics and assessed perceptions of and satisfaction with the EHR system at baseline and at the 2 follow-up time points. Questions were drawn from published surveys and studies assessing physicians’ and other providers’ satisfaction with EHRs.6,10,11 Thirty-two survey items were grouped by consensus (ABM, MKW, CA) into 12 domains based on clinical and practice relevance and to facilitate presentation of trends (Table 2).

Table 2.

Survey items, grouped by domain, capturing provider perceptions of EHR benefit

| Domain | Individual items |

|---|---|

| Overall satisfaction | Overall satisfaction |

| Productivity | Improved productivity |

| Overall patient safety | Overall patient safety |

| Better care | Better patient care |

| Medical record completion burden | Charting after hours – reduced medical record completion burden |

| Patient safety and quality | Positive impact on clinical decision quality |

| Avoidance of drug errors | |

| Avoidance of drug allergies | |

| Avoidance of potentially dangerous drug interactions | |

| Critical lab value alerts | |

| Communication | Facilitated provider communication |

| Facilitated patient communication | |

| Information exchange | Hospital transition – easy access to relevant clinical information during transitions of care |

| Easy access – allowed access, storage, and retrieval of patient information | |

| Timely information – timely and accurate information available to provider | |

| Preventive care | Preventive care delivery – delivery of guideline-based preventive care |

| Preventive care prompt – provided preventive care because of prompt | |

| Preventive lab prompt – ordered laboratory test because of prompt | |

| Clinical workflow | Scheduling consults – decreased time scheduling consults |

| Receive consult reports – decreased time getting consult results | |

| Monitoring patients – increased time tracking and monitoring patients | |

| More time for patients – spent more time on other aspects of patient care | |

| Coordination of care – increased coordination between departments | |

| Scheduling patients – facilitated patient scheduling process | |

| Drug refills – assisted prescription refills | |

| Access to records – provided access to medical records | |

| Technical support and access | Computer access – sufficient access to computers with EHRs |

| Adequate resources to help with solving EHR problems | |

| General satisfaction | Satisfaction with ease of use for direct patient care |

| Satisfaction with reliability of system | |

| Satisfaction with sharing medical information with other providers | |

| Satisfaction with obtaining medical information from providers |

Statistical analyses

Summary statistics were used to describe respondents’ characteristics and compare the characteristics of those who completed all 3 surveys vs those who did not. Using an established approach, survey response options were collapsed into 2 categories to facilitate analysis and interpretation (eg, agree vs disagree, satisfied vs dissatisfied, yes vs no; see categories for each item in Supplementary Table A).6 Based on published approaches that group “uncertain” and “undecided” responses with negative responses, response options of “uncertain” were categorized into a “not agree” category for questions that included the “uncertain” option.2 Because some elements of the EHR may not be relevant to the practices of all providers (ie, preventive care, critical lab alerts, drug allergies, medication interactions), responses from providers that indicated “not applicable” for these items were not included in the analyses. Of note, with the exception of preventive care prompt and preventive laboratory prompt, which had “not applicable” rates ranging from 19% to 29%, the rates of “not applicable” for the 3 other items with this response option were low (ranging from 3% to 7%). We hypothesized higher utilization and relevance of EHR technology and thus higher perceived EHR benefit among providers with outpatient practices and younger providers, and those in primary care among providers with outpatient practices.12,13 Thus, stratified analyses were conducted by practice setting (inpatient only vs any outpatient) and by age (≤45 vs >45 years) and clinical specialty (primary care vs medical or surgical specialty) for those with outpatient practices. Given the small number of providers with inpatient practices only (n = 29), the differences in perception of this group compared to providers with any outpatient practice, and the fact that primary care vs specialty care references providers in outpatient settings, we limited the age- and specialty-specific subgroup analyses to providers with outpatient practices.

For each survey item, a random effects logistic regression model was used to assess whether providers’ responses changed over 3 points in time (baseline, short-term follow-up, and long-term follow-up). This analytic technique allowed investigators to test whether survey item responses differed across the 3 time points while also (1) adjusting for potential confounding variables (age, gender, provider type, clinical specialty, and experience using the EHR) and (2) accounting for intra-individual correlation using a random intercept. For each logistic regression model, the survey item served as the dependent variable. Predictor variables included the time of the survey and potential confounders. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.14 Changes (increase or decrease) in percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit on each survey item over time were deemed to be significant when P < .05. All analyses were conducted using R version 3.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

At the time of baseline assessment, there were 1263 providers in the system; 520 were determined to be ineligible for the study (eg, trainee, not using EHR). Of the 743 eligible providers, 460 (61.9%) completed at least 1 survey, 303 (40.8%) completed 2 surveys, and 223 (30.0%) completed all 3 surveys (Figure 1). For our analyses, we focused on changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit from baseline to long-term follow-up and included providers who completed all 3 surveys. Provider characteristics of those who did and did not complete all surveys are included in Table 3. There were no differences by age, gender, provider type, or practice setting between providers who did and did not complete all 3 surveys. Completers were more likely than non-completers to have >5 years’ experience using the EHR. Overall, those included in our analyses were primarily male, ≥45 years of age, physicians, practicing a specialty other than primary care in both inpatient and outpatient settings, and had >5 years’ experience using the basic EHR.

Table 3.

Provider participant characteristics

| Survey completion | Completed all surveys (n = 223) (%) | Completed 1 or 2 surveys (n = 237) (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 59.2 | 57.4 | .8062 |

| Female | 40.8 | 42.2 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.4 | |

| Age | |||

| 26–35 years old | 11.7 | 18.1 | .2029 |

| 36–45 years old | 31.8 | 33.8 | |

| 46–55 years old | 28.7 | 21.9 | |

| 56–65 years old | 20.6 | 20.7 | |

| >65 years old | 7.2 | 5.5 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Provider type | |||

| Physician provider | 77.6 | 80.6 | .4967 |

| Other provider | 22.4 | 19.4 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Clinical specialty | |||

| Primary care | 23.8 | 25.3 | .0446 |

| Medical specialty | 26.0 | 26.2 | |

| Surgical specialty | 21.5 | 18.6 | |

| Hospital medicine | 7.6 | 7.2 | |

| Emergency medicine | 5.8 | 5.9 | |

| Anesthesia | 4.9 | 3.0 | |

| Mental health services | 0.4 | 3.4 | |

| Laboratory/radiology services | 4.9 | 4.2 | |

| Other | 1.3 | 1.7 | |

| Missing | 3.6 | 4.6 | |

| Practice setting | |||

| Outpatient | 85.7 | 86.9 | .8979 |

| Inpatient only | 13.0 | 12.2 | |

| Missing | 1.3 | 0.8 | |

| Experience with local EHR | |||

| <6 months | 0.4 | 1.7 | .0002 |

| 6 months to 1 year | 3.6 | 5.9 | |

| >1–5 years | 30.0 | 43.9 | |

| >5 years | 65.5 | 48.5 | |

| Missing | 0.4 | 0 | |

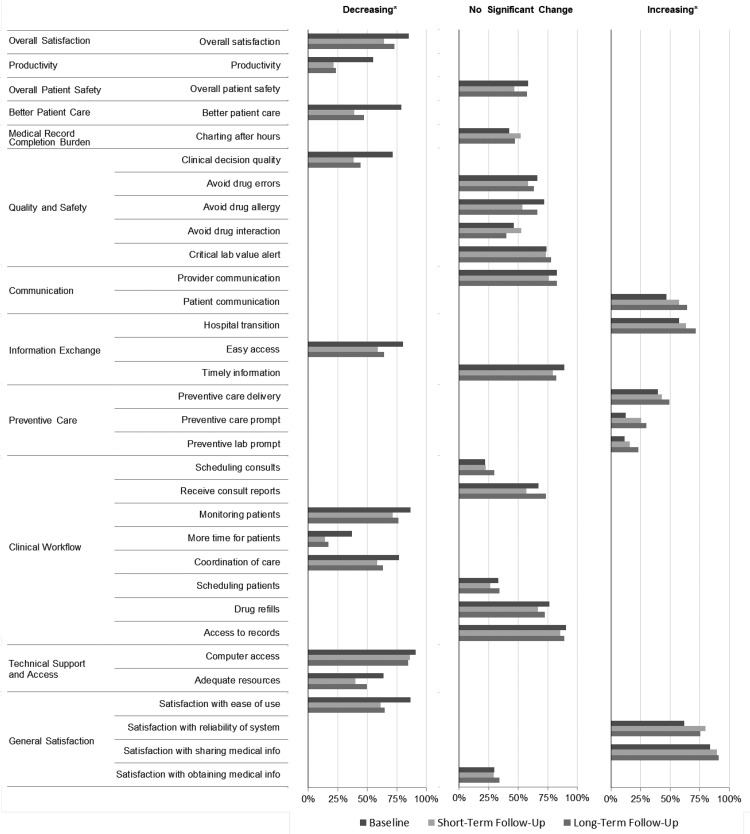

Analyses assessed changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit and were first conducted among the entire study population (Figure 2; Supplementary Table A) and then explored among prespecified subgroups (Table 4; Supplementary Table B). We analyzed and reported changes across the 3 time points (baseline to short term, short term to long term, and baseline to long term; Figure 2 and Table 4; Supplementary Tables A and B) in an effort to assess whether there was a “dip” in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions immediately after implementation of the commercial comprehensive EHR and a “recovery” over longer follow-up. We highlight the changes from baseline to long-term follow-up throughout this paper, because these reflect the longer-term perceptions of providers after the initial disruption following the introduction of a new technology.

Figure 2.

Multivariable-adjusted changes in overall percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit grouped by increasing, no significant change, and decreasing from baseline to long-term follow-up. Significant changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit from baseline to short-term follow-up, short-term to long-term follow-up, and baseline to long-term follow-up (eg, % satisfied, % agree) are presented based on multivariate-adjusted analyses. Change in each item was adjusted for age, gender, provider training (physician vs other provider), setting (inpatient vs any outpatient), time using electronic health records; P-values were also adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Results are grouped by direction of the change (increasing, no change, decreasing) from baseline to long-term follow-up.

Table 4.

Comparison of multivariable-adjusted changesa in percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit

| Domain | Individual Items | Practice Setting |

Age |

Specialty |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient Only | Any Outpatient | <= 45 | > 45 | Primary Care | Medical Specialty | Surgical Specialty | ||

| Overall satisfaction | Overall satisfaction | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | – | – |

| Productivity | Productivity | – | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | – | ↓ | ↓ |

| Overall patient safety | Overall patient safety | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Better care | Better patient care | – | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | – | ↓ | ↓ |

| Medical record completion burden | Charting after hours | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Patient safety and quality | Clinical decision quality | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | ↓ |

| Avoid drug errors | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Avoid drug allergy | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Avoid drug interaction | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Critical lab value alert | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Communication | Provider communication | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Patient communication | – | ↑ | ↑ | – | ↑ | – | – | |

| Information exchange | Hospital transition | – | ↑ | ↑ | – | ↑ | – | – |

| Easy access | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | |

| Timely information | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | – | – | |

| Preventive care | Preventive care delivery | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – |

| Preventive care prompt | – | ↑ | – | ↑ | ↑ | – | – | |

| Preventive lab prompt | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Clinical workflow | Scheduling consults | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Receiving consult reports | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Monitoring patients | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | – | – | |

| More time for patients | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | |

| Coordination of care | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | |

| Scheduling patients | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Drug refills | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Access to records | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Technical support and access | Computer access | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Adequate resources | – | – | – | ↓ | – | – | – | |

| General satisfaction | Satisfaction with ease of use | – | ↓ | – | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | – |

| Satisfaction with reliability of system | – | ↑ | – | ↑ | ↑ | – | – | |

| Satisfaction with sharing medical information | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | |

| Satisfaction with obtaining medical information | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

aSignificant changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions from baseline to long-term follow-up (eg, % satisfied, % agree) based on multivariate-adjusted analyses. Change in each item was adjusted for age, gender, provider training (physician vs other provider), setting (inpatient vs any outpatient), time using electronic health records. P-values were also adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.14

Increase ↑, no significant change –, decrease ↓ from baseline to long-term follow-up.

OVERALL ANALYSIS

Results of analyses conducted among the entire study population show significant increases in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit between baseline and long-term follow-up for patient communication (47.09–64.55%; P < .01), access to clinical information during hospital transitions (57.66–71.95%; P < 0.01), preventive care delivery that meets guidelines (39.91–49.32%; P = 0.02), preventive care prompt (12.43–30.19%; P < .01), preventive lab order prompt (11.43–22.94%; P = 0.02), satisfaction with system reliability (62.16–75.45%; P < .01), and satisfaction with sharing medical information with the system hospital and providers (83.78–91.36%; P = .03). Significant decreases in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit between baseline and long-term follow-up were seen for overall satisfaction (85.14–73.06%; P < .01), productivity (54.95–23.32%; P < 0.01), better patient care (78.83–47.09%; P < .01), clinical decision quality (71.30–44.34%; P < .01), easy access to patient information (80.18–64.13%; P < .01), monitoring patients (86.49–76.13%; P < .01), more time for patients (36.94–17.04%; P < .01), coordination of care (77.03–63.23%; P < .01), access to computers with EHR (90.99–84.75%; P = .04), adequate resources to solve EHR problems (63.51–49.78%; P = .01), and satisfaction with ease of use for direct patient care (86.49–64.86%; P < .01). Although there was a significant decrease in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit between baseline and long-term follow-up for these items, it is interesting to note the presence of an upward trend (though not exceeding baseline values) between short-term and long-term follow-up for all of the items except access to computers with the EHR (Figure 2; Supplementary Table A).

SUBGROUP ANALYSES BY PRACTICE SETTING, AGE, AND SPECIALTY

Table 4 highlights significant changes from baseline to long-term follow-up in percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit by practice setting, and by age and specialty for providers with outpatient practices. Detailed data regarding changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit across the 3 groups from baseline to short-term and long-term follow-up are provided in Supplementary Table B.

Changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit by practice setting – inpatient only vs any outpatient (Table 4): There were no significant changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit in the inpatient-only practice setting from baseline to long-term follow-up. For providers with outpatient practices, there were significant increases from baseline to long-term follow-up in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit for patient communication (51.83–67.37%; P < .01), access to clinical information during hospital transitions (53.68–70.53%; P < .01), guideline-based preventive care delivery (40.31–49.74%; P = .02), preventive care prompt (13.33–31.43%; P < .01), and satisfaction with the reliability of the system (58.42–76.06%; P < .01). The percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit decreased for overall satisfaction (85.26–73.94%; P = 0.01), productivity (51.58–19.37%; P < .01), better patient care (78.42–47.12%; P < .01), clinical decision quality (71.20–44.44%; P < .01), easy access to patient information (79.47–63.87%; P < .01), timely information (90.53–81.48%; P = .02), monitoring patients (88.42–75.26%; P < .01), more time for patients (35.26–14.14%; P < .01), coordination of care (80.00–65.45%; P < .01), and satisfaction with ease of use (86.32–64.74%; P < .01).

Changes in percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit by age, ≤45 years of age vs >45 years of age among providers with any outpatient practice (Table 4): For providers who were ≤45 years old, the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit increased from baseline to long-term follow-up for patient communication (50.63–78.48%; P < .01) and access to clinical information during hospital transitions (49.37–74.68%; P = .03). The percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit decreased for productivity (55.70–27.85%; P < .01) and better patient care (75.95–45.57%; P < .01).

In the older group, the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit increased from baseline to long-term follow-up for preventive care prompt (13.19–32.94%; P = .01), satisfaction with system reliability (58.93–74.55%; P = .01), and sharing medical information with system hospitals and providers (80.36–92.86%; P = .02). The percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit declined for overall satisfaction (86.49–65.45%; P < .01), productivity (48.65–13.39%; P < .01), better patient care (80.18–48.21%; P < .01), clinical decision quality (75.00–39.09%; P < .01), easy access (79.28–56.25%; P < .01), timely information (90.99–78.18%; P = .01), monitoring patients (90.09–72.97%; P < .01), more time for patients (34.23–8.93%; P < .01), coordination of care (80.18–60.71%; P < .01), adequate resources to solve EHR problems (61.26–46.43%; P = .04), and satisfaction with ease of use (84.82–56.25%; P < .01).

Changes in percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit by specialty, primary care vs medical subspecialty among providers with any outpatient practice (Table 4): For primary care providers, the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit increased from baseline to long-term follow-up for patient communication (60.78–90.20%; P = .01), access to clinical information during hospital transitions (45.10–74.51%; P = .02), preventive care prompt (12.5–54.0%; P < .01), and satisfaction with system reliability (29.41–84.31%; P = .01). The percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit decreased at long-term follow-up for satisfaction with ease of use (86.27–62.75%; P = .02).

Among the medical and surgical specialties, there were no items for which the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit significantly increased from baseline to long-term follow-up. For both medical and surgical specialty providers, the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit significantly decreased at long-term follow-up for productivity (medical: 59.62–19.23%, P < .01; surgical: 60.87–23.4%, P < .01) better patient care (medical: 88.46–40.38%, P < .01; surgical: 78.26–44.68%, P = .02), and clinical decision quality (medical: 78.85–39.22%, P < .01; surgical: 68.09–36.96%, P = .04); results were qualitatively similar to the overall analyses. In addition, for medical subspecialties, additional items for which the percentage of providers with positive perceptions decreased included easy access (82.69–59.62%; P = .03), more time for patients (44.23–15.38%; P < .01), coordination of care (90.38–71.15%; P = .04), and satisfaction with ease of use (94.12–64.71%; P < .01).

DISCUSSION

While comprehensive EHRs have been designed to facilitate health care delivery and enhance patient safety,1,2 insufficient data are available on health care provider perceptions of EHR benefits. After a transition from a local basic EHR to a commercial comprehensive EHR, we identified items with significant increases and decreases and others with no significant change in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit from baseline to long-term follow-up. In addition, the items with significant changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions from baseline to long-term follow-up varied by provider practice setting, and by age and specialty practice for those with outpatient practices, although the trends were generally qualitatively similar across groups. For most items, there was an initial decline at short-term followed by an upward trend at long-term follow-up, though a J-curve pattern was not generally observed. These results may provide insight into the challenges and opportunities associated with transitioning from a local basic EHR to a commercial comprehensive EHR.

The items for which the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit increased over time were in the domains of communication, information exchange, preventive care, clinical workflow, and general satisfaction with system reliability. These improvements on specific items were expected, given system upgrades with the comprehensive EHR and prior research.2,14–16 Further, the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit significantly decreased over time in the domains of overall satisfaction, productivity, better patient care, quality and safety, technical support, and access (and trended upward between short-term and long-term follow-up). In addition, specific items in the domains of information exchange, clinical workflow, and general satisfaction showed decreases in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit after the transition (eg, easy access, more time for patients) despite reported improved perceptions of some items within these domains (eg, access to information during hospital transition). These results may be related to the technical challenges in transitioning to a comprehensive EHR from a local basic EHR. In addition, the local basic EHR had been iteratively optimized to fit provider workflows and likely met most clinician needs prior to the transition, thus the added value of the comprehensive EHR, which had not been optimized yet to fit local workflows and care teams, may not have been readily apparent during the study follow-up. The observed decreases in this study regarding the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of productivity and ease of use may reflect suboptimal integration of the EHR with local workflows and care teams.

Despite the initial decrease in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of the benefits of the EHR, it may be that the increase in technology uptake over time together with optimization to fit local workflows and care teams may improve use of the EHR and increase positive perceptions of benefits in the long term.7 If providers’ perceptions of EHR benefit (eg, it facilitates delivery of guideline-based preventive care, it prompts providers to provide a flu vaccine or order a colonoscopy) are reflected in actual improvements in preventive care delivery, including appropriate vaccines and cancer screening, and subsequent decreases in rates of influenza and severity of colon cancer at time of diagnosis, then the added value of the EHR in preventing disease and improving health outcomes in the long term may be demonstrated.

A recently published study of a 2-year prospective longitudinal survey of ambulatory care providers in family medicine, general pediatrics, and internal medicine reported perceptions about a second-generation EHR among physicians with experience using an existing locally developed EHR.8 Although Hanauer et al. hypothesized that perceptions would follow a J-curve pattern and suggest a successful EHR implementation, a J-curve was not found for any measure, including workflow, safety, communication, and satisfaction. The authors noted that further research is warranted to determine whether positive perceptions exceed baseline over longer periods of time and what interventions can assist physicians in using EHRs more effectively.8 Our longitudinal study of provider perceptions extends this prior work to include a broader group of health care providers and explore subgroup analyses by provider age, specialty, and practice setting to better understand provider perceptions of EHR implementation. We found that perceptions varied and did not generally follow a J-shape pattern. It is possible that longer-term follow-up may show a continued trend upward and a J-curve response.

Data are limited on differences in provider perceptions of EHR benefit and satisfaction by subgroups. We explored differences with respect to the items that significantly changed in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit by provider practice setting and age, and by specialty for those with outpatient practices. For providers with outpatient practices, we found that younger providers (≤45 years) showed an increase and older providers (>45 years) showed a decrease in the percentage of those with positive perceptions of EHR benefit on a greater number of items (Table 4). For older providers, most of the items for which there was a decrease were related to the use of new technology (eg, technical support, clinical workflow, information exchange, and medical record completion burden). Compared to the specialist groups, primary care providers showed an increase in the percentage of those with positive perceptions of EHR benefit over time on a greater number of items. These data align with the goal of EHRs to overcome barriers in primary care and general practice. Nevertheless, the decreases in perceptions of EHR benefit among primary care providers are important to note, particularly clinical decision quality and better patient care. Given that comprehensive EHRs are designed to facilitate communication with patients, information exchange, clinical alerts, and preventive care, the increases in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit in patient communication, access to information during hospital transition, and preventive care prompts by providers in outpatient settings were also expected.2,15–17 Although the trends in the changes of percentage of providers with positive perceptions for those with inpatient practices only were qualitatively similar to those with outpatient practices, the small sample size (n = 29) may have limited the ability to detect significant differences; larger studies assessing the impact of EHRs on inpatient provider perceptions are needed. Given that the subgroup analyses were meant to be exploratory and generate hypotheses for future studies, we did not test for interaction effects, but instead examined trends across subgroups. Larger studies that are adequately powered for subgroup analyses should investigate the impact of EHRs on providers stratified by specialty, practice setting, and age.

Prior research has noted a large gap between the postulated and empirically demonstrated benefits of eHealth technologies, including EHRs, and the need for data on empirical evidence for the beneficial impact of these technologies on clinical outcomes.18 Studies have yielded mixed results on the relationship between EHR use and quality of care.5,15,19 Linder15 found no consistent relationship between EHR use and the quality of ambulatory care. Poon et al.19 found that although there were no significant associations between EHR use and performance on Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measures, use of certain features of EHRs (such as cancer screening and prevention) by primary care providers was associated with better performance on certain quality indicators. This lack of consistent evidence that EHR use translates into improvements in clinical practice may be due in part to a lack of clinical decision support or of appropriate use of decision support. In our study assessing changes in provider perceptions of EHR benefit using a comprehensive EHR with clinical decision support, the decrease in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit for the clinical decision support items suggests that technical barriers may have been present. If there are technical barriers to using EHR systems, these will likely limit implementation in routine clinical practice. Thus, our work supports earlier reports that mandatory implementation of a comprehensive EHR does not guarantee that providers will perceive the benefits of the system.20 If providers have continued concerns regarding the benefits of EHRs to assist in clinical decision quality and patient care, this could negatively impact full implementation of EHR technology in routine clinical practice and minimize the potential for improved patient outcomes and safety. Careful consideration of why the benefits of comprehensive EHR technology are not perceived by health care providers is needed.

Limitations and strengths

The results of this study must be considered in light of its limitations. This survey assessed provider perceptions of EHR benefits and satisfaction with various constructs of the EHR; we did not measure factors such as provider proficiency using the EHR, assessment of care team workflow redesign, level of comfort using the EHR, or health care outcomes. The study was observational, and thus causal inferences cannot be made. The study population included health care providers within a large, nonprofit, multispecialty academic health care system in the United States participating in health care delivery reform and with mandatory EHR adoption. The response rate for completing all 3 surveys was 30%; however, low response rates for physicians/providers does not necessarily introduce bias.21–26 In our study, various nonresponse scenarios were possible: providers with low perceptions of EHR benefit may have chosen not to respond and/or to leave the organization, resulting in a positive bias; unhappy providers may have been more likely to complete the survey, resulting in a negative bias.8 Of note, there were no differences by age, gender, provider type, or practice setting between providers who did and did not complete all 3 surveys. Completers were more likely than non-completers to have more experience using the EHR; however, we do not have reason to believe that length of experience using the EHR was differentially related to the main study outcome, change in perception of EHR benefit over time. We were not able to compare the demographic characteristics of providers who did not respond to any survey with our those of survey responders, because the data were not available. The results represent responses by providers who were primarily male, ≥45 years of age, physicians, practicing a specialty other than primary care in both inpatient and outpatient practice settings, and had >5 years’ experience using the basic EHR. Sample sizes for the subgroups were small, limiting analyses and interpretation of findings. Thus, these results may not be generalizable to all health care providers implementing EHRs.27 Minor updates to the commercial EHR were made during implementation in response to provider needs, and one major upgrade was made after implementation to increase the set of tools and standard features of the commercial EHR during the study. The impact of the major upgrade on our results was likely minimal, given that it was concurrent with the final follow-up survey for ∼10% of the providers participating in the survey; only 15 of these providers did not respond to the long-term follow-up survey. Although the changes were designed to increase functionality, the changes associated with upgrades could have resulted in provider frustration, which may have negatively influenced the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit. Longer-term follow-up studies that track provider perceptions of EHR benefit after implementation, major system upgrades, and system optimization with local workflows and care teams are needed to assess whether perceptions improve as provider proficiency with EHR technology improves and workflow redesign and care teams are optimized.

There are several strengths of the study. It adapted previously established survey items, and the findings reflect the perceptions of health care providers in a large, integrated multispecialty group practice in the southeast region of the United States following a mandatory transition from a local basic EHR to Epic, which is the most frequently implemented commercial EHR nationwide, with 194 921 meaningful use attestations (18.88%).28 The study also assessed changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit at 3 time points to determine trends and explored results by provider practice setting, age, and specialty.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

The results of this study provide data on changes in the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit among a diverse pool of health care providers following mandatory implementation of a commercial EHR within a health care system with experience using a local basic EHR. In some but not all areas, the data reveal that while comprehensive EHRs are designed to improve the quality and safety of patient care, health care providers do not necessarily perceive these benefits. What is not clear is why there is this disconnect for some of the items. Is it an issue of usability of the EHR tool or a need for EHR optimization with local workflow and care teams? Or perhaps the technology is not delivering on the proposed benefits. Further work and longer follow-up are needed to evaluate the use of EHRs in diverse real-world settings after optimization with local workflow and care teams, to understand the barriers to implementation in different provider groups, and to assess the link between EHR use, provider perceptions, quality of care, and clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSION

After the transition from a local basic EHR to a commercial comprehensive EHR, we identified areas where the percentage of providers with positive perceptions of EHR benefit significantly increased and some areas where it significantly decreased from baseline to long-term follow-up. A better understanding of provider perceptions regarding EHR benefit may provide insight into usability of the technology and lead to approaches to improve EHR integration in clinical practice.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Carol Legendre, Susan Muery, Andreas Rubiano, and Jami Yarbrough for their outstanding staff assistance with the logistics of this survey study.

References

- 1. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S et al. , Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;14410:742–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. King J, Patel V, Jamoom EW, Furukawa MF. Clinical benefits of electronic health record use: national findings. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1 Pt 2):392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. New Engl J Med. 2010;3636:501–04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Henry J, Pylypchuk Y, Talisha Searcy MPA, Patel V. Adoption of Electronic Health Record Systems among US Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals: 2008-2015. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; May 2016. Report No. 35. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou L, Soran CS, Jenter CA et al. , The relationship between electronic health record use and quality of care over time. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;164:457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR et al. , Electronic health records in ambulatory care: a national survey of physicians. New Engl J Med. 2008;3591:50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paré G, Raymond L, de Guinea AO et al. , Barriers to organizational adoption of EMR systems in family physician practices: a mixed-methods study in Canada. Int J Med Inform. 2014;838:548–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanauer DA, Branford GL, Greenberg G et al. , Two-year longitudinal assessment of physicians’ perceptions after replacement of a longstanding homegrown electronic health record: does a J-curve of satisfaction really exist? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;24:e157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Otieno OG, Toyama H, Asonuma M, Kanai-Pak M, Naitoh K. Nurses’ views on the use, quality and user satisfaction with electronic medical records: questionnaire development. J Adv Nurs. 2007;602:209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gamm LD, Barsukiewicz CK, Dansky KH, Vasey JJ, Bisordi JE, Thompson PC. Pre- and post-control model research on end-users’ satisfaction with an electronic medical record: preliminary results. Proc AMIA Symp. 1998;225–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O’Connell RT, Cho C, Shah N, Brown K, Shiffman RN. Take note(s): differential EHR satisfaction with two implementations under one roof. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;111:43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morton ME, Wiedenbeck S. EHR Acceptance Factors in Ambulatory Care: A Survey of Physician Perceptions. American Health Information Management Association; http://library.ahima.org/doc?oid=106752. Accessed August 23, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Series B (Methodological). 1995;571:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Linder JA, Ma J, Bates DW, Middleton B, Stafford RS. Electronic health record use and the quality of ambulatory care in the United States. Arch Int Med. 2007;16713:1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis Giardina T, Menon S, Parrish DE, Sittig DF, Singh H. Patient access to medical records and healthcare outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;214:737–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wright A, Soran C, Jenter CA, Volk LA, Bates DW, Simon SR. Physician attitudes toward health information exchange: results of a statewide survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;171:66–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Black AD, Car J, Pagliari C et al. , The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic overview. PLoS Med. 2011;81:e1000387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Poon EG, Wright A, Simon SR et al. , Relationship between use of electronic health record features and health care quality: results of a statewide survey. Med Care. 2010;483:203–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Linder JA, Schnipper JL, Tsurikova R, Melnikas AJ, Volk LA, Middleton B. Barriers to electronic health record use during patient visits. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006;2006:499–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bjertnaes OA, Garratt A, Botten G. Nonresponse bias and cost-effectiveness in a Norwegian survey of family physicians. Eval Health Prof. 2008;311:65–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McFarlane E, Olmsted MG, Murphy J, Hill CA. Nonresponse bias in a mail survey of physicians. Eval Health Prof. 2007;302:170–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cull WL, O’Connor KG, Sharp S, Tang SS. Response rates and response bias for 50 surveys of pediatricians. Health Serv Res. 2005;401:213–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flanigan TS, McFarlane E, Cook S. Conducting survey research among physicians and other medical professionals: a review of current literature. In: Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods Section, American Statistical Association. 2008. www.amstat.org/sections/srms/proceedings/y2008/Files/flanigan.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001;201:61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Menachemi N, Hikmet N, Stutzman M, Brooks RG. Investigating response bias in an information technology survey of physicians. J Med Syst. 2006;304:277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heisey-Grove D, Danehy L-N, Consolazio M, Lynch K, Mostashari F. A national study of challenges to electronic health record adoption and meaningful use. Med Care. 2014;522:144–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. CMS Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive Program, Electronic Health Record Products Used for Attestation. HealthData.gov. www.healthdata.gov/dataset/cms-medicare-and-medicaid-ehr-incentive-program-electronic-health-record-products-used. Accessed September 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.