Abstract

Objective

Problem list data is a driving force for many beneficial clinical tools, yet these data remain underutilized. We performed a systematic literature review, pulling insights from previous research, aggregating insights into themes, and distilling themes into actionable advice. We sought to learn what changes we could make to existing applications, to the clinical workflow, and to clinicians’ perceptions that would improve problem list utilization and increase the prevalence of problems data in the electronic medical record.

Materials and Methods

We followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines to systematically curate a corpus of pertinent articles. We performed a thematic analysis, looking for interesting excerpts and ideas. By aggregating excerpts from many authors, we gained broader, more inclusive insights into what makes a good problem list and what factors are conducive to its success.

Results

Analysis led to a list of 7 benefits of using the problem list, 15 aspects critical to problem list success, and knowledge to help inform policy development, such as consensus on what belongs on the problem list, who should maintain the problem list, and when.

Conclusions

A list of suggestions is made on ways in which the problem list can be improved to increase utilization by clinicians. There is also a need for standard measurements of the problem list, so that lists can be measured, compared, and discussed with rigor and a common vocabulary.

Keywords: medical records systems, computerized, medical records, problem oriented, medical records, problem oriented/standards, problem list, thematic analysis, systematic review

OBJECTIVE

Electronic problem lists provide many potential benefits to clinicians: they are a source of evidence-based recommendations,1–6 they streamline clinical trial recruitment7–9 to the point where one can signify interest with the click of a button,2,10–12 they allow diagnoses to follow patients to other health care settings to save time and money,13–15 and they aid clinicians and researchers in later determining which treatments are the most effective.8 These benefits are a powerful motivator that makes manual16 or automated17–20 maintenance of problem lists worthwhile, so that patients can receive the best care.21 Our objective was to find the benefits of maintaining problem lists and identify critical keys for success.

To gain that understanding, we performed a systematic literature review, pulling insights from previous research, aggregating insights into themes, and distilling themes into actionable advice. Ultimately, we sought to learn what changes we could make to existing applications, to the clinical workflow, and to clinicians’ perceptions.

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Medical records aid clinicians in their primary duty of caring for patients. Maintaining accurate problem lists helps clinicians track patient status, to avoid omissions in care and organize clinical reasoning and documentation.3,21,22 This is just as useful for a first-time patient visit as it is when there are long gaps between patient visits.23,24

Maintaining a complete record of each patient’s issues is expected of clinicians, not simply for billing and research or legal requirements, but because it is clinically useful for them to do so.3 However, as work pressures mount, thoroughness and order of record-keeping often are the first casualties.25 Increasing haphazardness can lead to overlooked and underdocumented patient issues, especially since there is no clearly defined criteria describing the minimally required content to document.25 These documentation issues persist because medical practice lacks a true system of care.26

These shortcomings have led to inaccurate, incomplete, and out-of-date problem lists.27 Thirty to 50% of the time, important chronic conditions are omitted from a patient’s problem list.3,28,29 This may be due to disagreement about what actually belongs on a problem list.7 Governing bodies do not agree on an accepted definition of the problem list,30–38 leaving the decision to individual clinicians. This leads to inappropriate items being added to problem lists, such as “narcotics contract,” “Jehovah’s Witness,”3 and “med refill.”39

For those who wish to utilize the problem list to its fullest, there is no consensus about what types of problems belong on the list. Should they add acute or chronic problems, family history, or social problems?7 There is also no consensus about the ideal time to update the problem list. Should the problem list be updated in real time, allowing evidence-based guidelines and decision support to be leveraged, or at the conclusion of a visit or admission, omitting intermediate differential diagnoses and focusing instead on only the discharge diagnoses, or long after the patient visit, meeting only the billing deadline for an encounter diagnosis?

Problem granularity is also an issue. Is it best to add cardiomegaly, edema, hepatomegaly, and shortness of breath as 4 separate problems on the list, or to enter the cohesive problem of cardiac failure, which encapsulates all 4 problems?25 Is it sufficient for a clinician to add a problem of “broken arm,” or should “fracture of right distal ulna” be added?

The question of who is responsible for maintaining the problem list is also left unanswered.40 Primary care providers generally do a better job of maintaining more accurate problem lists,41 but specialists and hospitalists often reap benefits from the maintained lists.3 Absent a policy of ownership, many clinicians opt to leave lists as is, ultimately leading to out-of-date problems.

Recent shifts toward team-based care, such as medical homes and accountable care organizations, are pushing better record-keeping to the forefront.13 These shifts may help clinicians realize that a well-maintained problem list enables them to deliver better patient care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To obtain a broad overview and consensus of opinion on problem lists, including their use, content, and positive and negative aspects, we gathered information from decade’s worth of published literature on the subject. We followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)42 to curate a corpus of pertinent articles. We then performed a thematic analysis,43 treating each article that met our inclusion criteria as a transcript from an interview, looking for interesting excerpts and ideas. By aggregating these excerpts from many authors, we gained broader, more inclusive insights into what makes a good problem list, and what factors are conducive to its success.

Data sources

We favored sensitivity over specificity, and searched as broad a range of sources as possible—specifically: PubMed, Scopus, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature from the beginning of time up to March 10, 2016. We searched using permutations of these terms: problem list, problem-oriented medical record, problem-oriented record, problem-oriented charting, problem summary list, problem-oriented patient record, problem-oriented system, and weed system. Results were limited to human subjects. All of the search results were downloaded in BibTeX format and imported into EndNote X7. Once all the search results were stored in EndNote, the exclusion criteria were applied.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We used the broad Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Meaningful Use guidelines44 to define a problem list as “a list of current and active diagnoses as well as past diagnoses relevant to the current care of the patient.” The problem-oriented medical record45 is a higher standard that many modern systems do not meet; it requires notes, orders, and medications to be linked to a diagnosis. We favored the less stringent problem list definition over the problem-oriented medical record definition when necessary.

All article types were included, since we performed a thematic analysis intended to identify aspects critical to success. Articles were excluded if they were duplicates from other sources, not in English (or not transcribed into English), or not primarily related to the problem list as defined above. Even if an article discussed problem lists prominently, it was typically excluded if its main purpose was to circumvent usage of the problem list, such as automatically adding to the problem list using natural language processing or clinical decision support techniques.

Articles that pertained mostly to narrow medical specialties were also excluded, since they could have specialized workflows that did not account for broader aspects of patient health. Articles were later excluded during the data analysis phase if their content did not contribute to one of the themes reported (see Data analysis section). Because the thematic analysis of such a large corpus could result in many dozens of themes, and because we were looking for larger, generally agreeable themes, a theme was removed from consideration unless it had at least 10 different sources corroborating a similar concept.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts from retrieved references were reviewed to determine if they met inclusion criteria. In cases where the focus of the article was unclear from the title and abstract, the entire paper was retrieved and read until it was evident. This was completed by a single reviewer (CMH).

Data extraction

It was clear from the onset that most articles discussing problem lists would not report quantitative metrics. We thus departed from PRISMA after the corpus was amassed, and instead analyzed the qualitative content using thematic analysis, which is based on Grounded Theory.46 We extracted general information from each article, such as setting and design type, but were primarily interested in the qualitative statements from the authors themselves: conclusions, insights, and interesting thoughts pertaining to the problem list. For this phase, we filled out a template text document for each included article. Our overarching research questions were simple: What are the best practices for using a problem list? and What are suggestions for ways to improve the success of the problem list?

Data analysis

All included articles were read and annotated, and we believe that saturation was achieved due to repeating ideas and concepts from the corpus. The content of each article’s extracted notes was aggregated into larger research question documents, without attribution. Attribution was stripped out during aggregation because it was important to have all ideas treated equally, regardless of author, journal, or year published.

Next, we used an inductive method of coding the aggregate content into basic codes, letting the content guide formation of the codes rather than any of our preconceived notions. An open coding approach was taken, and was conducted by a single reviewer (CMH). This led us to a list of several succinct codes, with all pertinent content listed under those codes.

Finally, larger themes were sought from the codes. These themes were meant to identify broader meaning from the data. In this phase, snippets were re-attributed, so a distinct count of articles per theme could be determined. If a code did not advance a meaningful theme, it was discarded. If a theme did not have at least 10 corroborating sources, it was discarded. Thus, even though an article might have met all the inclusion criteria and helped guide formation of the codes and themes, it may have been excluded simply by not addressing a theme of shared interest.

RESULTS

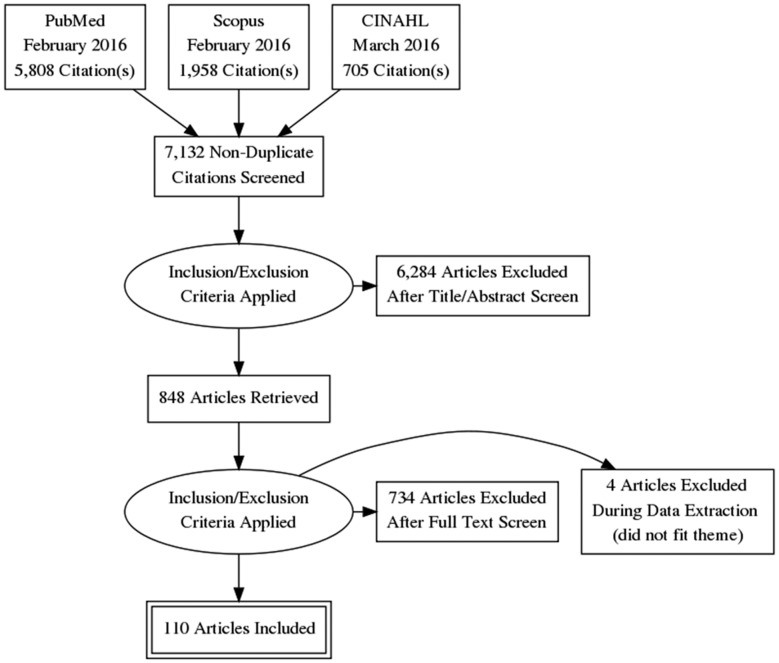

The literature search returned a total of 7132 unique references; 6284 articles were excluded based on relevance after screening of title and abstract. We reviewed the remaining 848 full-text articles, of which 110 met the criteria for inclusion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

With this corpus, the first question we wanted to answer was: What benefits have been listed by past authors for clinicians who use the problem list? If we can convince a clinician that there is value in using the problem list, then this effort has been well spent.

Benefits of using problem list

We used thematic analysis to build a list of all reasons authors cite for using the problem list. We looked for any phrases that mentioned benefits they received or reasons they believed an up-to-date problem list is worth the effort. Those snippets were then stratified into like-kind groups, and then organized into themes, shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Benefits/reasons for using a problem list, sorted by reference count

| Theme/reason | Benefit/example | References | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient safety | Patient safety, care coordination, transitions of care communication, improved care quality, improved completeness, and follow-up | 2–4,6,7,14,16,20–22,24,27,47–77 | 43 |

| Workflow/organization | Reduced time spent reviewing records, easier to find information when needed, easier to cover patients for another provider, memory aids | 3,4,6,14,20,23,25,47,50–52,55,59,60,62,65,66,68,69,77–87 | 30 |

| Automation/knowledge augmentation | Reminders, clinical decision support alerts, clinical practice guidelines, automatic ordering suggestions | 2,6,16,20,50–52,54,66,69,73,77,80,84,86,88–96 | 24 |

| Education/assessment | Detailed records make it possible to assess a medical student’s thought process, basis for rounds, can be used for clinician assessment, teaching | 3,6,14,22,47–49,52,58–62,65,70,74,83,91,97–101 | 22 |

| Enticed to use it | Financial incentives, organizational expectations, legal compliance | 3,20,47,50–52,55,56,58,62,68,69,72,84,89,95 | 16 |

| Required to use it | Meet regulatory, accreditation, or reporting requirements | 4,7,14,27,48,50–52,56,66,77,80,93,94 | 14 |

| Research | Better understanding of population served, comparative effectiveness studies | 6,7,14,48,50,52,59,65,74,80,85,92,102 | 13 |

The unused problem list

Although there are many benefits to using the problem list, there are also reasons why clinicians choose not to maintain it. Common reasons are duplicate problems, old problems, cluttered problem lists, disagreement about what belongs on the problem list, and a lack of perceived value from using the problem list.21,28,41,57

However, after reading the included literature, there did not appear to be a single agreed-upon reason that would explain clinician reluctance toward the problem list. For this reason, we looked for a more encompassing rationale. The many reasons authors listed for why the problem list was not used can be grouped under one theme explained by the “social fence” theory put forth by Platt et al.103,104 A social fence is described as an individual hesitating or avoiding a task, which in turn leads to a loss for an entire group. Because the benefits of using the problem list may accrue to a downstream user of the problem list, there is little reward for diligent maintenance.

Aspects critical to success

We saved snippets of text that related to problem list best practices and suggestions on how the problem list could be improved. These snippets were sorted into like-kind categories. Emergent themes are listed in Table 2. Some concepts apply to multiple themes.

Table 2.

Aspects critical to success for using a problem list, sorted by reference count

| Theme | Aspects critical to success | References | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationships between problems and data | Link a problem to its supporting progress notes, administrative data, and supporting clinical data, such as observations, findings, symptoms, imaging, and medication data. Link a problem to itself and other problems to depict clinical relationships. | 13,21–23,25,29,50–52,54,55,57,58,60,62,65,67,69,74,77,79,82–85,87,88,91,94,95,97,99,100,105–118 | 47 |

| Coding | All problems should be coded with clinician-friendly display terms, backed by links to a standard terminology concept. Codes should represent clinical concepts only, not financial or administrative. Coded concepts should not include acronyms without spelling them out. Nor should any terminology such as Systematized Nomenclature for Medicine or International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions be accepted wholesale; instead, only those commonly used by local clinicians should be canonized. | 3,6,7,14,29,41,47,50–52,56–58,60,63,66,68,72,74,77,81,90,91,94,96,97,106,110,111,113,115,118–127 | 40 |

| Knowledge aids (clinical decision support systems [CDSS]/evidence-based medicine [EBM]) | Use coded problems data and CDSS to assist clinicians in following best practices by alerting them to evidence-based medicine guidelines in real time. Remind clinicians about follow-up care and potential research trials for which the patient may be eligible. | 2–4,7,14,16,20,21,48–50,52,54,55,69,72,73,76–78,80,84,86,88,89,91–96,108,110,111,125,128,129 | 37 |

| Education/performance measurement | Clinicians need to be trained on the organization’s policy and expectations of how to use the problem list. Clinicians also need to know how the problem list data will be used downstream, so they can understand its importance. Clinicians should be using the problem list in rounds as a way to evaluate students’ understanding of patients’ health, and as a way to understand individual clinician performance and outcomes. | 3,14,22,23,25,47,48,50–52,56,58,60,65,70,72,91,95,98–100,125,130,131 | 24 |

| Specificity | Problems should be coded to the level of current understanding. The terminology system used to code problems should not offer too many similar or detailed options, to avoid nearly identical problem list item duplicatio and burdensome clinician use, and to make downstream aggregation of data simpler. Organizations may wish to determine how specific a problem list entry should be: add the encompassing syndrome or each constituent problem individually. | 3,7,22,25,41,52,56–58,60,61,63,66,67,74,77,85,106,110,119–121,125,132 | 24 |

| Different views | Allow clinicians to see the problem list in many different ways so they can tailor it to best fit their needs. The single longitudinal problem list can be filtered, sorted, grouped, subsumed, rolled up, listed, or graphed until it meets clinicians’ needs. These preferences should persist between sessions for individual clinicians. | 3,14,29,49,50,52,57,65,67,77,81,83,90,91,97,106,109,111,112,114,115,117,133 | 23 |

| Policy | Organizations should work with clinicians to develop a policy that addresses what types of problems belong on the problem list, who is responsible for maintaining the list, when the list should be updated, the patient’s role in maintaining the list, and which specific problems are added to the list. | 3,4,7,14,21,50–52,57,58,62,69,72,74,77,91,93,99,101,110,125,134 | 22 |

| Workflow | Adding to and using the problem list should be flexible enough for clinicians to find the way that works best for them, while clinicians choosing the right actions should be enforced, saving clinician time overall. | 3,23,24,29,49,50,52,55,58,62,72,74,77,78,80,86,90,91,93,95,117 | 21 |

| Searching and adding/easy problem entry | Search results should be returned quickly, with a small set of the most common concepts at the top of the list, hiding obscure concepts. There should be the ability to search by term, acronym, or synonym. Use defaulted data and precoordination to save clinician time and clicks when entering. Items already on the problem list should not be returned in the search results, or, if added, should obscure older entries. | 7,22,29,50,52,55,57,58,66,68,86,91,96,97,111,113,115,120–122,135 | 21 |

| Multidisciplinary | Problem lists should contain contributions from all members of the care team, including nurses, nutritionists, and respiratory therapists. A complete problem list focusing on all patient care areas improves interdisciplinary communication, care coordination, and transitions of care. | 14,22,23,47,50,52,55,58,65,69,72,76,77,82,91,99,110,112,119 | 19 |

| Nonproblems/sensitive problems | A separate area to add notes should exist close to the problem list so clinicians can add nonclinical notes to it rather than to the problem list. This can also serve as a place to store sensitive information the clinician may not want the patient to see, but not diagnoses. There should be a flag that can mark a problem as sensitive, hiding it from the patient or other clinicians. | 3,7,50,52,56–58,67,69,71,77,82,93,111,127 | 15 |

| Longitudinal | A single problem list should exist for each patient spanning from conception to death, so that history of illnesses and evolution of problems over time are visible to all caregivers. | 4,29,49,58,62,65–67,75,77,81,83,108,112 | 14 |

| Financial incentives | Early phases of adoption may require financial incentives until it has become a part of the culture. This may be in the form of pay-for-performance goals or direct financial incentives. However, this might also take the form of tangential incentives, such as linkages to improve clinician billing, higher patient throughput via improved workflow, or decreased readmission rates. Clinicians also respond to financial disincentives, such as lower reimbursement rates or penalty payments. | 3,50,52,58,61,72,77,84,89,93,95,99,111,121 | 14 |

| Patient facing | Empower and engage patients. Allow patients to see their problem lists to suggest additions and deletions to keep the list accurate. Allow patients to prioritize problems in the order they feel is most important to them. Link patients to educational material and support communities with similar diagnoses. | 3,13,22,50,54,55,57,58,71,77,91,93,110 | 13 |

| Culture/leadership buy-in | Problem lists are more successful if an organization values their use and embeds that desire within its culture. This can occur when goals and financial incentives align to reinforce use when senior clinicians and upper management expect lists to be used, and when the organization touts the benefits from maintained use, such as research findings and time savings. | 3,7,14,56–58,72,89,93,99 | 10 |

Policy

Evidence suggests that one reason problem lists are not used effectively is simply because there is no standard agreement among clinicians on how they should be used.3,4,7,14,50–52,56–58,62,72,74,77,89,91,93,99,110,125 This may be because they were never trained on proper use23,50–52,58,72,91,95,100 or are unaware of, or disagree with, proposed benefits (see Table 1) or financial incentives.3,44,50,52,58,61,72,84,89,93,95,99,121 A best practice principle arose, stating that simply taking the time as an organization to work with clinicians and develop a policy for use would improve problem list utilization and, as a result, list completeness and care quality.4,6,7,20,21,24,50,51,56,57,59,61,64,65,67,69,73,111

When sorting the related snippets into this theme, it became clear that a policy should address the following points at a minimum: what types of problems belong on the problem list, who is responsible for maintaining the list, and when the list should be updated. Several other snippets indicated that it is important to address the patient’s role in maintaining the list, as well as the specificity of problems on the list. The following sections explore these points in more detail.

What belongs on the problem list?

According to Wright, there is considerable disagreement about what types of problems belong on the problem list.3 Weed himself never clearly defined what a “problem” was, merely stating that problems were “aspects of the patient's condition which need attention.”25,117 Many articles relating to problem lists focus on a specific aspect of use at a single facility. However, by aggregating the ideas from many peer-reviewed articles, we gained insight into how various writers have defined problem lists. For Table 3, a list of problem types was generated using inductive logic. While many articles implied the types of problems they allowed on their problem lists, only those that stated them explicitly were included in this table.

Table 3.

What belongs on a problem list, sorted from most to least common mention

Who should maintain the problem list?

Most articles implied that physicians were the sole maintainers of problem lists. However, only those that stated it explicitly were included. Table 4 does not suggest that a maintainer is the sole person to maintain, only that he or she can or should. In fact, there is strong evidence that the entire multidisciplinary team should take ownership.14,22,23,47,50,52,55,57,58,65,69,72,77,82,91,99,110,112,119

Table 4.

Who should maintain the problem list, and when it should be maintained

| Who should maintain | References | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Physicians – shared | 22,23,35,50,52,57,58,72,76,77,82,89,91,93,99,110,112 | 17 |

| Primary care physician | 30,41,57,58,91,93 | 6 |

| In part | 41,57,91,93 | |

| Sole | 30,58 | |

| Specialist | 4,30,41,57,58,91,93 | 7 |

| Only their dx | 4,30,57,58,93 | |

| Any dx | 41,57,91,93 | |

| Patient | 13,50,54,55,57,58,71,77,91,93,110,112 | 12 |

| All team members/multidisciplinary | 22,47,55,57,58,65,69,72,91,93,110,119 | 12 |

| When to maintain | ||

| Each encounter (before, during, or after) | 3,21,23,24,29,49,55–58,72,77,95,101,102,127 | 16 |

| Real time (as data become available) | 25,44,52,69,74,86,93,102,111,115 | 10 |

| During rounds | 22,23,48,60 | 4 |

| Third encounter | 35,57,77 | 3 |

| Yearly/yearly physical | 57,93 | 2 |

| Not until 24 h later | 25,134 | 2 |

| Transition of care | 55,58 | 2 |

| After intervention | 90,109 | 2 |

When should the problem list be updated?

Many articles describe what should be on the problem list, few describe who should update the problem list, and a rare few make mention of when the problem list should be updated. There were some implied time frames, but only explicit statements were included. For instance, several articles suggested that clinical decision support rules should fire to prompt clinicians to update the problem list. However, it was not specified when these rules triggered, so they were excluded. Since so few articles matched criteria for these themes, the inclusion threshold was lowered to just 2.

DISCUSSION

Problem lists themselves are not complicated; they just live in a complicated ecosystem. As such, minor software changes will never be enough to satisfy all clinicians’ needs. Instead, a multifaceted approach must be taken, which includes all stakeholders and touches on all the necessary aspects of finance, legal, policy, regulation, patient outcomes, care coordination, and clinician workflow. To address these aspects, the following list of suggestions for improvements to the problem list has been compiled:

Linking clinical data such as imaging, labs, procedures, and medication orders to a diagnosis on the problem list can be enforced in the computerized physician order entry system. However, linking one diagnosis to another to show sequelae relationships is harder to enforce, yet that depiction is important to convey the current clinical thinking. Reviewing problem lists during rounds, looking specifically for these interrelationships, and updating the list to document these relationships would help ensure an accurate clinical story.

Forcing clinicians to use coded terms is unpopular, even after converting to physician-friendly display text. The ability for clinicians to add free-text concepts to the problem list is essential, because not all concepts will be coded, or a clinician may refer to a concept differently. A feedback mechanism may help by identifying free-text entered problems, alerting the terminology team to either add the term to the dictionary or suggest possible equivalent coded concepts, and accept that term into the patient’s problem list, replacing the free-text entry.7,29,111

In order to receive the full benefits of automated decision support, clinicians must receive clinical decision support systems (CDSS) output while they are face-to-face with patients. As clinicians interact with the system by entering new problems, the rules engine is able to assimilate those data and make suggestions for the patients’ benefit. Other methods, such as natural language processing, that process results asynchronously can circumvent that real-time interaction, giving results in a delayed manner,20 of lower quality,93,102,111 and for reasons not even related to patient care.50

Using problem lists during rounds as a mentoring method is a strong motivator for student use of the problem list. However, nonstudents will need other reasons to use the problem list. One possibility is to show stats every month that list each clinician’s score for using it and patient outcomes. This may ignite healthy competition among clinicians. Alternatively, highlight success cases that occur from clinicians using the problem list, such as saved time when seeing a new patient or new CDSS alerts that are enabled because of these data.

Zhou suggests an idea that may resolve the specificity issue. He states that the dictionary used to code problems should link differing levels of granularity of the same problems together: “diagnoses should be coded and should provide a hierarchy so that generalists can pick higher-level codes (eg, ‘heart disease’) whereas specialists could select more granular codes (eg, ‘double outlet right ventricle,’ a subset of ‘heart disease’).”77 Then, when using the application, there could be a “‘slider’ to adjust the level of granularity as needed, based on the clinical hierarchies, for the clinician reviewing the list,”77 which would work similarly when aggregating data for reports and research.

The goal of views is to reduce clutter, making it easier for clinicians to find content of interest. Klann and Schadow39 suggest a method that would improve this process by “gradually ‘fading out’ problems with little remaining information value.” Drury agrees, noting that processes could “automatically close acute problems using an automated algorithm.”108

-

When formulating a policy for an organization, it would be beneficial to discuss how the problem list should be used, so there is no confusion about who is responsible in a given situation. Knowing organizational expectations, such as checking a patient’s problem list prior to each office visit or during rounds, is helpful to set the culture. If the problem list is used as a measure of clinician assessment or compliance, or as an indicator of clinical practice guideline adherence to reduce practice variation, or as a source of downstream research, this needs to be stated explicitly, so team members can understand and embrace problem list usage, especially in a teaching environment.

Just as important as a policy regarding what content belongs on the problem list is a policy about what should not be on the list. Policy about not duplicating existing problems already on the list but instead updating older content will help ensure that the problem list does not become cluttered with unresolved duplicate entries. Additionally, the policy should note that the problem list should only be used for clinical treatment and not adulterated with financial or billing data,50,52,69,111,127 or with quick free-text reminders that do not affect patient care.

Bayegan suggests that the clinician’s workflow could be improved if the system could be aware of what the clinician is trying to do at any given moment.49 The system could then make problem list entry available from other components, such as during documentation. When the system notices that a clinician is writing patient notes, it could quickly highlight narrative content that may indicate a problem, and allow the clinician to add it to the problem list with a single click from the documentation module.29

When displaying search results to the clinician, one way to reduce the results set and to help enforce proper workflow is to hide any search matches that are already active on the problem list. This will remind the clinician to first resolve the existing problem before adding a new instance of it. Alternatively, problems that are already active on the problem list can be highlighted in the search results, alerting the clinician to potential duplicates. If selected, the system could automatically resolve the existing problem, if appropriate, before adding a new instance of the problem.29

Receiving data from multiple care disciplines adds breadth to the problem list, providing a broader view of the patient’s current health status. This would enable a deeper understanding of the comparative effectiveness of treatments and provide a richer database for more intricate CDSS logic.112

To help clinicians feel comfortable adding sensitive problems to the problem list, they could check a flag to mark a problem as sensitive. A sensitive problem could be hidden from patient-facing portals, insurance companies, or other clinicians, depending on organizational policies/preferences.7,77,93

Longitudinally orienting the problem list does not mean that problems cannot also be linked to a specific encounter. When adding a new problem to the list, a specified encounter can be linked, or the most recent encounter can be defaulted to reduce data entry time. This will still allow problems to be analyzed for administrative purposes.

It may be prudent to phase in the financial incentives, “focus[ing] on a population of high utilizers with ‘ambulatory sensitive conditions.’”84 By starting with a group of clinicians who are likely to see the most benefit from using the problem list, success can accrue. This gives the organization time to learn from that group’s experience before rolling out incentive plans to a larger audience, and also allows time for clinical champions to emerge, providing additional evidence of the problem list’s worth in subsequent rollouts.

The face-to-face mode of reviewing the patient’s problem list is the most meaningful, and also takes the most clinician time. As a solution, Gensinger states, “Subjective data can be recorded by the patient … before … brought back to the room to interact with the physician. New problems or concerns can be recorded by the nursing staff in the assessment section (eg, shortness of breath, cough, fatigue) which would then generate the workflow of necessary clinical data to be captured.”110 Wright agrees, noting that it would be beneficial for “patients to suggest problem list changes through a pre-visit form.”71 This would allow the limited time the clinician has to interact with the patient to be more focused on pertinent problems.

Embedding expectations from upper leadership is part of solidifying problem list usage in a culture. However, top-down mandates will not be enough to create a self-sustaining mentality that sees the benefits of the problem list. It will also be important for bottom-up grass-roots initiatives to take hold. By empowering clinicians to suggest improvements to the workflow, to problem list functionality, and to organizational policy and incentives, they will feel a sense of ownership.99

LIMITATIONS

The major limitation of this study is its subjective nature and the use of a single reviewer. When annotating all 110 articles to determine what content was applicable to the thematic analysis and when sorting snippets into themes, different reviewers may have focused on different content and reached different conclusions. This limitation was mitigated by aggregating ideas across all included articles and only discussing those with the most frequent mentions. By doing this, it is reasonable to conclude that other reviewers may have arrived at similar themes. In fact, just as this paper was about to be submitted, we came across another article139 that was published after our original inclusion date range that shows very similar themes, giving further validity to our methods and results.

Another limitation is that by focusing on the most heavily mentioned ideas, less common, more unique ideas may have been overlooked. Although unique ideas without much corroboration were excluded, we kept some of those ideas for use in the Discussion section as potential solutions to common problems.

CONCLUSION

The list of the 15 aspects critical to success that were identified in this paper focus on how the problem list should be used, the content that belongs on the list, and policies that enable these practices to be adhered to. Additionally, it is notable that there is no standard measurement for conveying improvements in the problem list. It is nearly impossible to know whether a change to a problem list intervention is positive or negative, making it impossible to measure the impact of that intervention or have a common vocabulary with which to discuss such impact.

This study has identified many ways to improve problem list maintenance, through either system improvements or promises of future rewards for doing so, or simply through mandates. However, the ultimate reason is, and should always be, because it will improve patient care.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

FUNDING

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONTRIBUTORS

CMH: primary author of the paper, devised the research topic and strategy, conducted the data gathering, processing, review, and analysis, as well as the article preparation and write-up. SPN: senior author of the paper, provided research direction, reviewed methodology and results, and helped with preparation and editing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pang JE, Wright A, Ramelson H et al. , Accurately identifying diabetic patients with problem list gaps. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:216–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wright A, Pang J, Feblowitz JC et al. , Improving completeness of electronic problem lists through clinical decision support: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;194:555–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wright A, Maloney FL, Feblowitz JC. Clinician attitudes toward and use of electronic problem lists: a thematic analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011;11:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wright A, Feblowitz J, Maloney FL, Henkin S, Bates DW. Use of an electronic problem list by primary care providers and specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;278:968–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright A, Goldberg H, Hongsermeier T, Middleton B. A description and functional taxonomy of rule-based decision support content at a large integrated delivery network. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;144:489–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warren JJ, Collins J, Sorrentino C, Campbell JR. Just-in-time coding of the problem list in a clinical environment .Proc AMIA Symp. 1998:280–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holmes C. The problem list beyond meaningful use part i: the problems with problem lists. J AHIMA. 2011;822:30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abend AHD, Johnson B. Integrating clinical data into the i2b2 repository. AMIA - Summit on Translat Bioinformatics. 2009;2:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas E, Lobach D. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330:765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buurma H, De Smet PAGM, Kruijtbosch M, Egberts AC. Disease and intolerability documentation in electronic patient records. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;3910:1640–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feblowitz J, Henkin S, Pang J et al. , Provider use of and attitudes towards an active clinical alert: a case study in decision support. Appl Clin Inform. 2013;4:144–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sidebottom AC, Collins B, Winden TJ, Knutson A, Britt HR. Reactions of nurses to the use of electronic health record alert features in an inpatient setting. Comput Inform Nursing. 2012;30:218–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mehta N, Vakharia N, Wright A. EHRs in a web 2.0 world: time to embrace a problem-list Wiki. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;293:434–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Acker B, Bronnert J, Brown T et al. , Problem list guidance in the EHR. J AHIMA. 2011;829:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tham E, Ross SE, Mellis BK, Beaty BL, Schilling LM, Davidson AJ. Interest in health information exchange in ambulatory care: a statewide survey. Appl Clin Inform. 2010;1:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lin J-H, Haug PJ. Exploiting missing clinical data in Bayesian network modeling for predicting medical problems. J Biomed Inform. 2008;411:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meystre S, Haug PJ. Automation of a problem list using natural language processing. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;530 https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1472-6947-5-30?site=bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meystre S, Haug PJ. Natural language processing to extract medical problems from electronic clinical documents: performance evaluation. J Biomed Inform. 2006;39:589–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meystre S, Haug PJ. Comparing natural language processing tools to extract medical problems from narrative text. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:525–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meystre SM, Haug PJ. Randomized controlled trial of an automated problem list with improved sensitivity. Int J Med Inform. 2008;779:602–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hartung DM, Hunt J, Siemienczuk J, Miller H, Touchette DR. Clinical implications of an accurate problem list on heart failure treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;202:143–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Feinstein AR. The problems of the ‘problem-oriented medical record.’ Ann Int Med. 1973;78:751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaplan DM. Clear writing, clear thinking and the disappearing art of the problem list. J Hosp Med. 2007;24:199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simborg DW, Starfield BH, Horn SD, Yourtee SA. Information factors affecting problem follow-up in ambulatory care. Med Care. 1976;1410:848–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach. N Eng J Med. 1968;278:593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weed LL, Weed L. Medicine in Denial: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. 2011: 280 p. http://infohistory.rutgers.edu/pdf/weed/medicine-in-denial.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lauteslager M, Brouwer HJ, Mohrs J, Bindels PJ, Grundmeijer HG. The patient as a source to improve the medical record. Fam Pract. 2002;192:167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Szeto HC, Coleman RK, Gholami P, Hoffman BB, Goldstein MK. Accuracy of computerized outpatient diagnoses in a Veterans Affairs General Medicine Clinic. Am J Managed Care. 2002;8:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hodge CM, Kuttler KG, Bowes WA 3rd, Narus SP. Problem management module: an innovative system to improve problem list workflow. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:661–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pocket Glossary of Health Information Management and Technology. 3rd ed Chicago: AHIMA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31. E1384-07(2013) A. Standard Practice for Content and Structure of the Electronic Health Record (EHR). West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Group EHRW. ISO/HL7 10781 EHR-System Functional Model, R1.1. Health Level Seven International; 2014.http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/product_brief.cfm?product_id=269. Accessed March 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Meaningful Use Definition Objectives: HealthIT.gov. 2015. https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/meaningful-use-definition-objectives. Accessed March 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Electronic Health Records (EHR) Incentive Programs. 2016. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/10/16/2015-25595/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-3-and-modifications. Accessed March 18, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals (CAMH). Joint Commission International; 2015. http://www.mitsstools.org/uploads/3/7/7/6/3776466/psc_for_web.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dick RS, Steen EB, Detmer DE. The Computer-Based Patient Record: An Essential Technology for Health Care, Revised Edition. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Final Ambulatory Functionality Criteria for 2007 Certification of Ambulatory EHRs. The Certification Commission for Healthcare Information Technology; 2007. https://www.cchit.org/files/Ambulatory_Domain/CCHIT_Ambulatory_FUNCTIONALITY_Criteria_2007_Final_16Mar07.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Inc. AAfAH. Accreditation Handbook For Ambulatory Health Care. Skokie, IL: AAAHC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klann JG, Schadow G. Modeling the information-value decay of medical problems for problem list maintenance. Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Health Informatics - IHI ‘10. New York, NY: ACM; 2010: 371–75. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wright A, Maloney F. Understanding problem list utilization through observational techniques. J General Int Med. 2010;25:S419–S20. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luna D, Franco M, Plaza C et al. , Accuracy of an electronic problem list from primary care providers and specialists. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:417–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moher D, Liberati A. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;67: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;32:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Meaningful Use Definition & Objectives: HealthIT.gov. 2015https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/meaningful-use-definition-objectives. Accessed March 17, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weed L. The problem oriented medical record. Perspective. 1973;8:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Strauss A, Juliet C. Grounded theory methodology: an overview In Denzin N, Lincoln Y. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 1994:273–84. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abrams JS, Davis JH. Advantages of the problem-oriented medical record in the care of the severely injured patient. J Trauma. 1974;145:361–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bakel LA, Wilson K, Tyler A et al. , A quality improvement study to improve inpatient problem list use. Hosp Pediatrics. 2014;44:205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bayegan E, Nytrø O, ed. A problem-oriented, knowledge-based patient record system. 17th International Conference of the European Federation of Medical Informatics, MIE 2002. Budapest; 2002: 2004176205. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bice M, Bronnert J, Goodell S, Herrin B, Scichilone R, Scott R. Problem lists in health records: ownership, standardization, and accountability. AHIMA. 2012. http://bok.ahima.org/PdfView?oid=106339. Accessed March 24, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bormel J. Problem lists are the keys to meaningful use. Put the big picture on your problem list. Health Manag Technol. 2011;322:40–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Campbell JR. Strategies for problem list implementation in a complex clinical enterprise. Proc AMIA Symp. 1998:285–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cheong PY, Goh LG, Ong R, Wong PK. A computerised out-patient medical records programme based on the Summary Time-Oriented Record (STOR) System. Singapore Med J. 1992;336:581–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Christensen T, Grimsmo A. Expectations for the next generation of electronic patient records in primary care: a triangulated study. Inform Primary Care. 2008;161:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Collins S, Tsivkin K, Hongsermeier T, Dubois D, Nandigam HK, Rocha RA, ed. A continuum of sociotechnical requirements for patient-centered problem lists. 14th World Congress on Medical and Health Informatics. MEDINFO. 2013; Copenhagen; 2013: 23920686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. De Lusignan S, Wells SE, Hague NJ, Thiru K. Managers see the problems associated with coding clinical data as a technical issue whilst clinicians also see cultural barriers. Methods Inform Med. 2003;424:416–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Holmes C, Brown M, Hilaire DS, Wright A. Healthcare provider attitudes towards the problem list in an electronic health record: a mixed-methods qualitative study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hummel J. Standardizing the Problem List in the Ambulatory Electronic Health Record to Improve Patient Care. Washington, Seattle: Qualis Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hurst JW. Ten reasons why Lawrence Weed is right. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:51–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kaplan DM. Perspective: whither the problem list? Organ-based documentation and deficient synthesis by medical trainees. Acad Med. 2010;8510:1578–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kushner I, Greco PJ, Saha PK, Gaitonde S. The trivialization of diagnosis. J Hosp Med. 2010;52:116–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Maino JH. The problem-oriented optometric record. J Am Optometric Assoc. 1979;508:915–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Manning PR. The problem oriented record as a tool in management. Clin Obstetrics Gynecol. 1975;18:175–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Margolis CZ, Mendelssohn I, Barak N, Beinart T, Goldsmith JR. Increase in relevant data after introduction of a problem-oriented record system in primary pediatric care. Am J Public Health. 1984;7412:1410–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Okuhara Y, Kitazoe Y, Narita Y et al. , New approach to the medical information system for quality management in patient care: development of Problem Mapping System. J Med Syst. 1999;235:377–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rothschild AS, Lehmann HP, Hripcsak G. Inter-rater agreement in physician-coded problem lists. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005;2005:644–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Salmon P, Rappaport A, Bainbridge M, Hayes G, Williams J. Taking the problem oriented medical record forward. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996:463–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Scherpbier HJ, Abrams RS, Roth DH, Hail JJ. A simple approach to physician entry of patient problem list. AMIA. 1994:206–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shires DB, Rozovsky L, Cameron AG. Just for the record: the problem-oriented approach. Can Fam Physician. 1974;20:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stratmann WC, Goldberg AS, Haugh LD. The utility for audit of manual and computerized problem-oriented medical record systems. Health Serv Res. 1982;171:5–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wright A, Feblowitz J, Maloney FL et al. , Increasing patient engagement: patients' responses to viewing problem lists online. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;54:930–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wright A, McCoy AB, Hickman TT et al. , Problem list completeness in electronic health records: a multi-site study and assessment of success factors. Int J Med Inform. 2015;8410:784–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wright A, Pang J, Feblowitz JC et al. , A method and knowledge base for automated inference of patient problems from structured data in an electronic medical record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;186:859–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. GledhlLl VX, Mackay IR, Mathews JD, Strickland RG, Stevens DP, Thompson CD. The problem-oriented medical synopsis applications to patient care, education, and research. Ann Int Med. 1973;785:685–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Samal L, Wright A, Wong BT, Linder JA, Bates DW. Leveraging electronic health records to support chronic disease management: the need for temporal data views. Inform Primary Care. 2011;192:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wright A, Chen ES, Maloney FL. An automated technique for identifying associations between medications, laboratory results and problems. J Biomed Inform. 2010;436:891–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhou X, Zheng K, Ackerman M, Hanauer D, ed. Cooperative documentation: the patient problem list as a nexus in electronic health records. ACM 2012 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW'12. Seattle, WA: ACM; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bayegan E, Nytro O, Grimsmo A. Ranking of information in the computerized problem-oriented patient record. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2001;84(Pt 1):594–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bayegan E, Tu S. The helpful patient record system: problem oriented and knowledge based. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002:36–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Brown SH, Miller RA, Camp HN, Guise DA, Walker HK. Empirical derivation of an electronic clinically useful problem statement system. Ann Intern Med. 1999;1312:117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bui AAT, Taira RK, El-Saden S, Dordoni A, Aberle DR. Automated medical problem list generation: Towards a patient timeline. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2004;107:587–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rind DM, Safran C. Real and imagined barriers to an electronic medical record. AMIA. 1993:74–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Van Vleck TT, Wilcox A, Stetson PD, Johnson SB, Elhadad N. Content and structure of clinical problem lists: a corpus analysis. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008;2008:753–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Weed LL, Zimny NJ. The problem-oriented system, problem-knowledge coupling, and clinical decision making. Phys Therapy. 1989;697:565–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hurst J. How to implement the Weed system: (in order to improve patient care, education, and research by improving medical records). Arch Int Med. 1971;1283:456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Schmidt EC, Schall DW, Morrison CC. Computerized problem-oriented medical record for ambulatory practice. Med Care. 1974;124:316–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Voytovich AE, Rippey RM, Suffredini A. Premature conclusions in diagnostic reasoning. J Med Educ. 1985;604:302–07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Decision support intervention prompts clinicians to update patients' problem lists in their medical records. AHRQ Res Activities. 2011;368:14–1. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Novotny B. Problem lists can threaten safety, pose liability risks. Healthcare Risk Manag. 2015;3710:116–17. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Adelhard K, Holzel D, Uberla K. Design elements for a computerized patient record. Methods Inform Med. 1999;383:187–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bonetti R, Castelli J, Childress JL et al. , Best practices for problem lists in an EHR. J AHIMA/Am Health Inform Manag Assoc. 2008;791:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Denekamp Y, Nasreldeen O, Peleg M. Characterization of the knowledge contained in diagnostic problem oriented clinical practice guidelines. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007:929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Holmes C. The problem list beyond meaningful use Part 2: fixing the problem list. J AHIMA. 2011;823:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Galanter WL, Hier DB, Fau-Jao C, Sarne D. Computerized physician order entry of medications and clinical decision support can improve problem list documentation compliance. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79:332–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Gandhi TK, Zuccotti G, Lee TH. Incomplete care — on the trail of flaws in the system. N Engl J Med. 2011;3656:486–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Wright A, Bates DW. Distribution of problems, medications and lab results in electronic health records: the Pareto principle at work. Appl Clin Inform. 2010;11:32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bossen C. Evaluation of a computerized problem-oriented medical record in a hospital department: does it support daily clinical practice? Int J Med Inform. 2007;768:592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Margolis CZ, Sheehan TJ, Stickley WT. A graded problem oriented record to evaluate clinical performance. Pediatrics. 1973;516:980–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sheldon MG. The problems of problem-orientated records. J Royal Coll Gen Pract. 1976;26167:437–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Stratmann WC. Assessing the problem-oriented approach to care delivery. Med Care. 1980;184:456–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Lloyd BW, Barnett P. Use of problem lists in letters between hospital doctors and general practitioners. Brit Med J. 1993;3066872:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Hebert C. Leveraging the electronic problem list for public health research and quality improvement [Doctoral dissertation]. The Ohio State University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Platt J. Social traps. Am Psychol. 1973;288:641–51. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hardin G. The tragedy of the commons. Science. 1968;1623859:1243–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Waisbren B. Letter: value of the problem-oriented record. JAMA. 1974;2301:37–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. De Clercq E. The index as a new concept towards an integrated framework for the electronic patient record. Methods Inform Med. 2002;414:313–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. de Lusignan S, Liaw ST, Dedman D, Khunti K, Sadek K, Jones S. An algorithm to improve diagnostic accuracy in diabetes in computerised problem orientated medical records (POMR) compared with an established algorithm developed in episode orientated records (EOMR). J Innov Health Inform. 2015;222:255–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Drury BM. Ambulatory EHR functionality: a comparison of functionality lists. J Healthcare Inform Manag. 2006;201:61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Elkin PL, Mohr DN, Tuttle MS et al. , Standardized problem list generation, utilizing the Mayo canonical vocabulary embedded within the Unified Medical Language System. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:500–04. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Gensinger RA Jr, Fowler J. ASOP: a new method and tools for capturing a clinical encounter. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1995:142–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Hayes GM. Medical records: past, present, and future. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996:454–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Henry SB, Holzemer WL. A comparison of problem lists generated by physicians, nurses, and patients: implications for CPR systems. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1995:382–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Krall MA, Chin H, Dworkin L, Gabriel K, Wong R. Improving clinician acceptance and use of computerized documentation of coded diagnosis. Am J Managed Care. 1997;34:597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Post A, Harrison J Jr. Data acquisition behaviors during inpatient results review: implications for problem-oriented data displays. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006:644–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Song F, Soukoreff RW. A cognitive model for the implementation of medical problem lists. Proc First Congress Comput Med, Public Health Biotechnol. Austin, Texas; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 116. Starmer J, Miller R, Brown S. Development of a structured problem list management system at Vanderbilt. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1998:1083. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Stitt FW. The problem-oriented medical synopsis: a patient-centered clinical information system. Proc Ann Symp Computer Appl Med Care. 1993:88–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Zelingher J, Rind DM, Caraballo E, Tuttle MS, Olson NE, Safran C. Categorization of free-text problem lists: an effective method of capturing clinical data. Proc Ann Symp Comp Appl Med Care. 1995:416–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Clark EM. Problem orientated records. Disease coding in a problem oriented general practice. J Royal Coll Gen Pract. 1974;24144:469–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Keck KD, Campbell KE, Chute CG. Supporting postcoordination in an electronic problem list. Proc AMIA Fall Congress. 1997;4:955. [Google Scholar]

- 121. Wang SJ, Bates DW, Chueh HC et al. , Automated coded ambulatory problem lists: evaluation of a vocabulary and a data entry tool. Int J Med Inform. 2003;72(1–3):17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Wilton R. Non-categorical problem lists in a primary-care information system. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1991:823–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Brown SH, Giuse DA. Cross-institutional reuse of a problem statement knowledge base. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:151–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Campbell JR, Payne TH. A comparison of four schemes for codification of problem lists. Proc Ann Symp Comp Appl Med Care. 1994:201–05. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Goldfinger SE. The problem-oriented record: a critique from a believer. N Engl J Med. 1973;28812:606–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Kuperman G, Bates DW, Gardner RM, Stead WW. Standardized coding of the medical problem list. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;15:414–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Payne TH, Murphy GR, Salazar AA. How well does ICD9 represent phrases used in the medical record problem list? Proc Annu Symp Comp Appl Med Care. 1992:654–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Altaher Mn, Buy U, Shatz S, Yu C, Hier D, Panko W. Computer-based system for problem list maintenance & medical informatics. Ann Int Conf IEEE Engineering Med Biol – Proc. 1997;3:949–52. [Google Scholar]

- 129. Wright A, Sittig DF, McGowan J, Ash JS, Weed LL. Bringing science to medicine: an interview with Larry Weed, inventor of the problem-oriented medical record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;216:964–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Hammett WH, Sandlow LJ, Bashook PG. Format review: evaluating implementation of the problem-oriented medical record. Med Care. 1976;1410:857–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Voytovich AE, Rippey RM, Copertino L. Scorable problem lists as measures of clinical judgement. Eval Health Prof. 1980;32:159–70. [Google Scholar]

- 132. Franco M, Giussi Bordoni MV, Otero C et al. , Problem oriented medical record: characterizing the use of the problem list at hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Spry KC. An infographical approach to designing the problem list. Proc 2nd ACM SIGHIT Symp Int Health Inform – IHI ‘12. New York, NY: ACM; 2012: 791–94. [Google Scholar]

- 134. Worthley LI. A system-structured medical record for intensive care patient documentation. Crit Care Med. 1975;35:188–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Poissant L, Taylor L, Huang A, Tamblyn R. Assessing the accuracy of an inter-institutional automated patient-specific health problem list. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2010;10:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Zaccagnini D. The problem with problem lists. Health Manag Technol. 2010;3111:30–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Longabaugh R, Fowler D, Stout R, Kriebel G Jr. VAlidation of a problem-focused nomenclature. Arch General Psychiatr. 1983;404:453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Woodruff DW. Patient problem list: 101 nursing tips. Nevada Rnformation. 2008;174:18. [Google Scholar]

- 139. Simons SMJ, Cillessen FHJM, Hazelzet JA. Determinants of a successful problem list to support the implementation of the problem-oriented medical record according to recent literature. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]