Abstract

Objective

Quantify physiologically acceptable PICU-discharge vital signs and develop machine learning models to predict these values for individual patients throughout their PICU episode.

Methods

EMR data from 7256 survivor PICU episodes (5632 patients) collected between 2009 and 2017 at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles was analyzed. Each episode contained 375 variables representing physiology, labs, interventions, and drugs. Between medical and physical discharge, when clinicians determined the patient was ready for ICU discharge, they were assumed to be in a physiologically acceptable state space (PASS) for discharge. Each patient’s heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure in the PASS window were measured and compared to age-normal values, regression-quantified PASS predictions, and recurrent neural network (RNN) PASS predictions made 12 hours after PICU admission.

Results

Mean absolute errors (MAEs) between individual PASS values and age-normal values (HR: 21.0 bpm; SBP: 10.8 mm Hg; DBP: 10.6 mm Hg) were greater (p < .05) than regression prediction MAEs (HR: 15.4 bpm; SBP: 9.9 mm Hg; DBP: 8.6 mm Hg). The RNN models best approximated individual PASS values (HR: 12.3 bpm; SBP: 7.6 mm Hg; DBP: 7.0 mm Hg).

Conclusions

The RNN model predictions better approximate patient-specific PASS values than regression and age-normal values.

Keywords: neural networks, patient discharge, electronic health records, pediatric intensive care units, supervised machine learning

Introduction

Patients in intensive care undergo high-frequency monitoring and are treated to achieve and maintain homeostasis, a state approximating health.1Homeostasis can be thought of as a composition of homeostatic volatility, the stability of a patient’s state over time, and homeostatic deviance, the distance of a patient’s current state from a medically acceptable state. An implicit goal of achieving homeostasis in an intensive care setting is restoring a patient’s physiological state towards a medically acceptable state. In practice, the values that determine this medically acceptable state are often estimated by the clinical team’s experience and expertise, and in general are not explicitly defined. Existing measures of health and mortality risk, like PRISM-III, PIM2, and PEWS, rely on the deviance of routine physiologic signs from explicitly defined normal values.2–4 Similarly, many ICU admission criteria5–8 include assessments of a patient’s mental and physical state, which base their standards of health on acceptable vitals.

Data describing age-normal vital signs and their implications in a clinical setting9–11 primarily focus on samples of healthy individuals from the general population. Recently, Fleming et al9 described issues with reference ranges of vital signs currently used in acute settings, and aggregated existing studies’ heart rate and respiratory rate baselines to generate centile distributions to update clinical guidelines. Studies have reported the age distribution of vital signs in hospitalized children12 and age-normalized centiles of vital signs in children in intensive care.13,14 There are also differences found in EMR data sourced from primary care vs intensive care patients.15 Nevertheless, quantifying how far a patient’s physiologic state deviates from acceptable during the ICU episode requires an explicit measure of a defined acceptable state.

The physiologic state of a critically ill child changes during an ICU episode. This can be represented as a dynamic system that transitions through multiple states over time. At any point in time, this dynamic system can be described as the patient’s state space, a multidimensional, mathematical characterization of the features that contribute to their condition. During an ICU episode, a successfully discharged child transitions through states of critical illness, stability, and a physiologically acceptable state space (PASS) for discharge from the ICU. The concept of PASS encompasses the physiologic state of health in which clinicians, based on all available information, have determined that a patient is acceptable for discharge from intensive care.

This study took advantage of the period between medical discharge and physical discharge from the ICU, during which ICU monitoring continued and was available in the EMR, to quantify 3 vital signs (HR, SBP, DBP) associated with the PASS. Determining whether features of an individual child’s PASS could be predicted by 2 machine learning methodologies (regression analysis and RNNs) was explored. The ability to predict features of PASS throughout their PICU stay may provide an explicit estimate of the patient’s homeostatic deviance from their PASS over time.

This study aims to quantify 3 vital signs as examples of features associated with PASS, and develop machine learning models to accurately predict these values for individual patients throughout the duration of their PICU stay.

Methods

Electronic Medical Records

The data were extracted from anonymized observational clinical data collected in Electronic Medical Records (EMR, Cerner Millennium, Cerner Corporation, Kansas City, Mo.) in the PICU of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) between January 2009 and October 2017. The CHLA Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed the study protocol and waived the need for IRB approval. An episode of ICU care was defined as one continuous stay. If a patient had multiple PICU admissions, these were considered separate episodes. Each episode had charted time series measurements for over 375 variables representing vital signs, laboratory results, interventions, and drugs. The full list of variables can be found in Clinical Data Used in the Supplementary Appendix.16 CHLA’s PICU also records the times of medical discharge, that is, the time the clinical team deems the patient healthy enough for discharge from the PICU, and physical discharge, the time the patient departs the PICU. The time from PICU admission to medical discharge is defined as the Pre-Medical Discharge (PMD) period, and the time from medical discharge to physical discharge defined as the Medical-to-Physical Discharge period. The Length of Stay is defined as the time from PICU admission to physical discharge from the PICU.

Previous work has discussed many of the complications regarding working with EMR data. Huff et al17 described electronic medical data encoded as linked events over time, and Lasko et al18 discussed many of the challenges in working with sparse, time-dependent pediatric EMR data. As such, a combination of pre-processing techniques is required to generate a matrix representation of EMR data amenable to machine learning algorithm development as previously described.16,19 Due to the sparse nature of charted medical data, pre-processing included imputation and normalization of variables. The resultant matrix is a sequence of feature vectors, where each row is associated with a variable over time, and each column is every variable at a time step. The matrix representation of a patient’s physiologic state space, as illustrated in Figure 1(a), has a 375-dimensional feature vector at each time point describing the patient’s state space. The pre-medical discharge and medical-to-physical discharge periods are shown in Figure 1(b).

Figure 1.

a) Data for a single episode is shown in a processed matrix format. A single row of data contains actual and imputed measurements from a single variable. A column of data comprises all measurements at one time point. Adapted with permission from.16 b) The means of a patient’s vitals between medical and physical discharge from the PICU define this patient’s PASS. Data from the pre-medical discharge period are used to predict individual PASS values.

Models were trained only on episodes from the population of 9879 episodes that met the definition of Successful Discharge; patients survived their PICU episode (9470 episodes) and were not readmitted within 48 hours (9310). A medical-to-physical discharge period of at least 2 hours (8476), and a length of stay of at least 12 hours (8327) were required. It was also required that at least 2 observations of heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure exist within the medical-to-physical discharge period. Within the final cohort of 7256 episodes (5632 patients), the 25th/50th/75th percentiles of length of stay were 33/60/120 hours, and the 25th/50th/75th percentiles of the medical-to-physical discharge period length were 5/9/27 hours, respectively.

Prior to analysis, the episodes were randomly split into training, validation, and test sets such that all episodes from a single patient belonged to only one of the 3 sets to prevent biasing test set metrics. Sixty percent of patients were in the training set (4399 episodes, 3398 patients), 20% in the validation set (1447 episodes, 1119 patients), and the remaining 20% in the test set (1410 episodes, 1115 patients).

The Physiologically Acceptable State Space

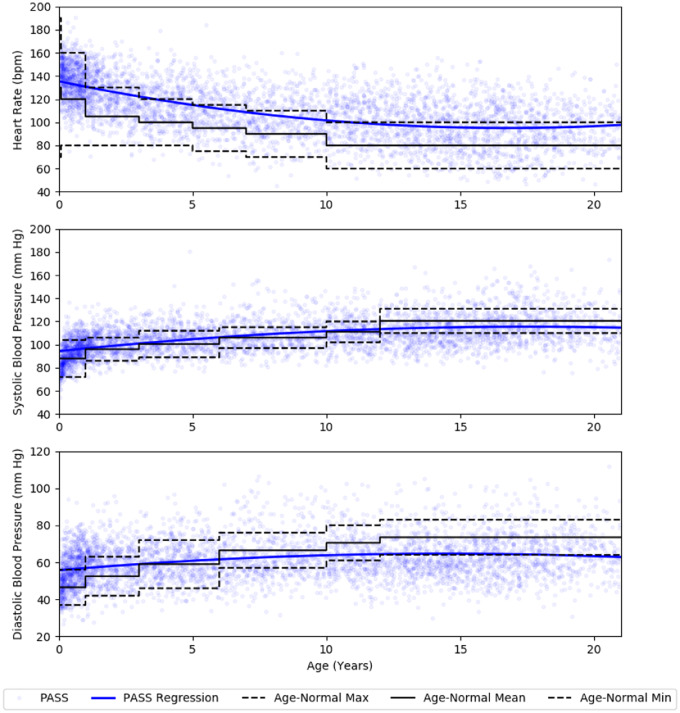

The concept of a patient’s Physiologically Acceptable State Space (PASS) encompasses the entire spectrum of values associated with successful ICU discharge. Delays between medical and physical discharge allow quantification of this state in patients successfully discharged from the ICU. As physiologic representatives of this state, a triad of vital signs was selected due to their importance in determining physiologic stability in the PICU.1,2,5 The means of heart rate (hr), systolic blood pressure (sbp), and diastolic blood pressure (dbp) within the medical-to-physical discharge period were calculated for each of the 7256 episodes, representing a portion of the physiologic state space considered acceptable for PICU discharge. This aggregation from the full EMR can be seen in Figure 1(b). This triad was used to demonstrate predictive modeling of a representative portion of features from the overall PASS distribution. Note that 3 variables do not determine the PASS, but are associated with the state. The heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure PASS values for each patient in the training set were plotted as a function of age in Figure 2 for comparison to published age-normal vital signs and age-dependent regression models.

Figure 2.

Published age-normal values, PASS values, and the PASS regression for heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure.

Age-normal Values

Published age-normal vital signs for heart rate9,20,21 and blood pressure11 were used for comparisons to machine learning model predictions. Age-normal values are traditionally given as ranges, as shown by Age-Normal Min and Age-Normal Max in Figure 2. To assess the machine learning models, the midpoint of the minimum and maximum normal values (shown as Age-Normal Mean in Figure 2) was used as a baseline.

Machine Learning Models for Predicting PICU-PASS

Predictions made by 2 machine learning methodologies, regression and RNNs, were compared to individual patients’ actual PASS values. A polynomial regression model was generated to estimate each PASS vital sign from age. The polynomial order for each model was selected by optimizing the model on the training set and selecting the order with the lowest error on the validation set. A fifth order polynomial was found to have the lowest error for each vital sign. The polynomial equations are found in Regression Polynomials in the Supplementary Appendix. These polynomials were used to generate PASS predictions on the test set episodes.

Predicting PASS using Recurrent Neural Networks

Because other factors than age likely influence the PASS, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) were trained to capture the relationships among these factors to predict individual patient PASS values. Designed with a feedback loop, RNNs can sequentially ingest and integrate time series data to learn temporal relationships.16,19 Specifically, Hochreiter’s Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture22 was used, as LSTMs can generate patient-specific predictions that update as more information is processed over time. Medical applications with successful RNN use include a time-varying severity of illness score,16 early detection of critical decompensation in children,23 onset of heart failure,24 de-identification of patient notes,25 and disease diagnosis from EMR.26

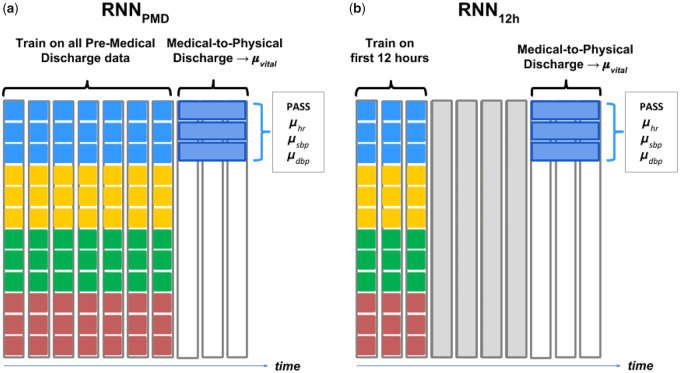

Because the PASS triad, [hr, sbp, dbp], is calculated from the medical-to-physical discharge period for each patient, data from this period was not included in our training process. Two RNN models with identical architecture (see RNN Architecture in the Supplementary Appendix) were developed, differing only in how the 2 models were trained. RNNPMD was trained on all data available prior to medical discharge, as shown in Figure 3(a). The second model, RNN12h, was trained on only the first 12 hours of data, as shown in Figure 3(b). Both RNN models were trained on the same patients, and both models can predict PASS at all time steps. These 2 models allowed comparisons of model performance between training on data near PICU admission (RNN12h) and training on all pre-medical discharge data (RNNPMD). Both RNN models were trained by minimizing prediction error in the validation set,27 and both models were then used to predict patient PASS values on the test set.

Figure 3.

a) During training, RNNPMD minimizes errors over all data prior to medical discharge. b) RNN12h minimizes errors over the first 12 hours after PICU admission. Both models predict mean heart rate (hr), systolic blood pressure (sbp), and diastolic blood pressure (dbp) derived from the medical-to-physical discharge period at every time step. During assessment, test set predictions are generated at the 12th hour following PICU admission for comparing model errors.

Assessment Metrics

The 1410 episodes in the test set were used to assess model predictions. The published age-norms, the values predicted from the regression, and both RNN model predictions made at the 12th hour following PICU admission were compared to each child’s measured PASS triad values. Mean absolute error (MAE) was used to compare model errors, defined by:

where N denotes the number of episodes in the test set. The notation vital(Pi) represents the PASS value for a vital (hr, sbp, or dbp) of the ith patient episode in the test set, while vital(Pi) denotes the model prediction for the same PASS value. For each patient’s episode, there is 1 true PASS value, 1 age-normal value, and 1 value determined by regression. In contrast, the 2 RNN models make predictions at every time step, as illustrated in Figure 4. To assess performance, RNN predictions made at the 12th hour following PICU admission were used to calculate MAEs. For pairwise model comparisons, two-sample t-tests28 between the PASS errors of the age-normal, regression, and RNN model predictions were calculated, with significant differences determined by p < .05.

Figure 4.

This figure contains predictions for one test set patient, age 12, throughout the course of their PICU episode. While the Age-Normal value (80) and PASS Regression prediction (97) are constant over time, the predictions of both RNNs are made at every time step of the patient’s episode. Note that only RNNPMD is shown for clarity. Our metrics assess the predictions made at the 12th hour, but predictions can be updated as new information enters the EMR over time.

To gain further insight into distinct PICU subpopulations, MAEs were calculated for several population subsets. Results were partitioned by pre-existing age-normal ranges, ICD-9 primary diagnoses for a better understanding of our model’s validity across distinct illnesses,29 and PIM2 score quartiles to better understand validity across severity of illness.3

Results

Table 1 displays the MAEs between the true PASS values and the age-normal values, regression predictions, and 2 RNN predictions, respectively. The regression predictions outperformed published age-normal values for all vital signs, with MAE reductions of 27% for heart rate, 8% for systolic blood pressure, and 19% for diastolic blood pressure (p < .05). RNNPMD compared to published age-normal values had MAE reduced 41% for heart rate, 30% for systolic blood pressure, and 34% for diastolic blood pressure. Compared to the regression predictions, RNNPMD had MAE reductions of 20%, 23%, and 19%, respectively (p < .05). There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 RNN models

Table 1.

Comparing mean absolute error (MAE) between patient-specific PASS vital signs, age-normal, age-dependent regression model, and 12th hour predictions from two RNN models

| Vital | Heart rate | Systolic Blood Pressure | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-Normal | 21.0 | 10.8 | 10.6 |

| Regression | 15.3*** | 9.7** | 8.5*** |

| RNN12h | 12.5***/*** | 7.8***/*** | 7.5***/*** |

| RNNPMD | 12.3***/***/. | 7.6***/***/. | 7.0***/***/. |

P-values of error comparisons to age-normal, regression, and RNN12h within the same column are denoted by sequential superscripts (.: p > .05, *: p ≤ .05, **: p ≤ .01, ***: p ≤ .001) in each cell. Bold numbers indicate the lowest error metric for a given vital.

Results for Select Diagnoses

Results were partitioned and compared by ICD-9 encoded primary diagnoses.29Table 2 displays the results for the 5 most common primary diagnoses in the dataset. Because it is possible for episodes to have more than 1 primary diagnosis, the diagnosis subsets in Table 2 are not necessarily isolated populations. Across all diagnoses and PASS vital signs, RNN12h and RNNPMD had the lowest errors of all 4 methods. Published age-normal heart rate values were not statistically different from the regression predictions for Brain Neoplasm patients.

Table 2.

Comparison of model performance, in MAE, parsed by the most common ICD-9 primary diagnoses in our dataset

| Vital | Diagnosis | Idiopathic Scoliosis | Brain Neoplasm | Acute Respiratory Failure | Asthma with Status Asthmaticus | Anomalies of Skull/Face Bones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 81 | 73 | 56 | 56 | 55 | |

| HR | Age-Normal | 31.3 | 15.5 | 22.6 | 30.8 | 18.1 |

| Regression | 19.4*** | 17.5 . | 14.8** | 17.8*** | 13.5 . | |

| RNN12h | 14.9***/* | 12.6./** | 13.0**/. | 15.8***/. | 11.9*/. | |

| RNNPMD | 14.4***/**/. | 12.7./**/. | 12.7***/./. | 15.3***/./. | 11.9*/./. | |

| SBP | Age-Normal | 11.5 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 7.9 | 11.4 |

| Regression | 10.2. | 8.6. | 9.2. | 7.0. | 9.5 . | |

| RNN12h | 8.4**/. | 7.8*/. | 7.6./. | 6.7./. | 7.7*/. | |

| RNNPMD | 7.8** | 7.8*/./. | 7.7././. | 6.6././. | 7.3**/./. | |

| DBP | Age-Normal | 12.8 | 10.7 | 8.8 | 9.3 | 11.2 |

| Regression | 7.8*** | 7.9* | 7.1. | 7.4 . | 7.3** | |

| RNN12h | 6.6***/. | 6.5***/. | 6.6*/. | 7.0./. | 7.0***/. | |

| RNNPMD | 6.3***/./. | 6.4***/./. | 6.3*/./. | 6.6*/./. | 6.4***/./. |

P-values of error comparisons to age-normal, regression, and RNN12h within the same column and vital are denoted by sequential superscripts (.: p > .05, *: p ≤ .05, **: p ≤ .01, ***: p ≤ .001) in each cell. Bold numbers indicate the lowest error metric for a given vital/diagnosis combination.

Results by Age-normal Bins

Results partitioned by age are shown in Table 3. Note that the heart rate and blood pressure bins are not identical due to different sources. Heart rate regression predictions showed improvement over published age-normal values across all bins except 0-1 month. Systolic blood pressure regression predictions had significantly lower MAEs than published age-normal values in the 1-12 months, 1-2 years, and 12+ years bins. For diastolic blood pressure, regression showed significant improvement over published age-normal values in the 1-12 months, 1-2 years, 10-11 years, and 12+ years bins.

Table 3.

Comparison of model MAEs parsed by pre-existing age bins from age-normal baselines. Note that the heart rate and blood pressure bins are not identical

| Vital | Age Bin | 0-1 Mos. | 1-12 Mos. | 1-2 Yrs. | 3-4 Yrs. | 5-6 Yrs. | 7-9 Yrs. | 10+ Yrs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 14 | 211 | 228 | 124 | 74 | 159 | 600 | |

| HR | Age-Normal | 16.7 | 19.3 | 21.5 | 19.5 | 20.6 | 20.4 | 22 |

| Regression | 11.0. | 13.4*** | 12.8*** | 14.7*** | 16.0* | 14.3*** | 17.3*** | |

| RNN12h | 8.9./. | 12.8***/. | 11.4***/. | 13.2***/. | 12.7***/. | 12.6***/. | 12.8***/*** | |

| RNNPMD | 9.3././. | 12.8***/./. | 11.4***/./. | 12.9***/./. | 12.6***/./. | 12.5***/./. | 12.3***/***/. | |

| Age Bin | <96 Hrs. | 1-12 Mos. | 1-2 Yrs. | 3-5 Yrs. | 6-9 Yrs. | 10-11 Yrs. | 12+ Yrs. | |

| Count | 2 | 223 | 228 | 157 | 200 | 91 | 509 | |

| SBP | Age-Normal | 2.8 | 11.2 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 12.1 |

| Regression | 12.8. | 9.4* | 8.1* | 10.2 . | 9.2. | 9.4. | 10.5** | |

| RNN12h | 5.4./. | 7.7***/** | 7.1***/* | 8.7*/. | 7.6*/** | 7.0*/** | 8.2***/*** | |

| RNNPMD | 6.6././. | 7.4***/***/. | 7.1***/*/. | 8.5*/*/. | 7.5**/**/. | 6.8**/**/. | 7.9***/***/. | |

| DBP | Age-Normal | 3.4 | 10.9 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 8.8 | 10.1 | 11.9 |

| Regression | 5.1. | 8.2** | 7.5*** | 9.6. | 8.2. | 7.8* | 8.9*** | |

| RNN12h | 3.3./. | 7.4***/. | 7.2***/. | 8.8./. | 7.4*/. | 6.5***/. | 7.4***/*** | |

| RNNPMD | 4.2././. | 6.9***/./. | 6.9***/./. | 8.0./*/. | 6.9**/*/. | 6.0***/*/. | 7.1***/***/. | |

P-values of error comparisons to age-normal, regression, and RNN12h within the same column and vital are denoted by sequential superscripts (.: p > .05, *: p ≤ .05, **: p ≤ .01, ***: p ≤ .001) in each cell. Bold numbers indicate the lowest error metric for a given vital/age bin combination.

Except in the youngest blood pressure bin, which only had 2 data points, the RNNs better approximated PASS values than age-normal values. For heart rate, the RNN models only had statistical improvements over regression in the 10+ years bin. For systolic blood pressure, at least 1 RNN model showed improvements over regression in all bins except the youngest. For diastolic blood pressure, at least 1 RNN model showed improvements over regression in all bins over 6 years old. There was no difference in the 2 RNN models’ performances in any bin.

Results by PIM2 Score

Table 4 displays model errors partitioned by PIM2 quartiles, where lower PIM2 scores indicate a lower severity of illness. The regression model showed improvements over age-normal approximations for heart rate and diastolic blood pressure across all PIM2 quartiles, and improvements in the 1st and 4th PIM2 quartiles for systolic blood pressure. For all vitals and all quartiles, the RNNs more closely approximated individual PASS values than age-normal values. Similarly, the RNN models outperformed regression across all conditions except the 4th quartile for heart rate predictions. There were no differences in model performance between the 2 RNNs.

Table 4.

Comparison of model performance, in MAE, parsed by PIM2 score quartiles

| Vital | PIM2 Quartile | 1st Quartile | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile Range | (−8.411, −6.31) | (−6.30, −4.83) | (−4.82, −4.15) | (−4.14, 2.53) | |

| HR | Age-Normal | 20.9 | 23 | 19.2 | 21 |

| Regression | 15.7*** | 15.9*** | 14.8*** | 14.7*** | |

| RNN12h | 12.7***/*** | 12.6***/*** | 11.5***/*** | 13.4***/. | |

| RNNPMD | 12.3***/***/. | 12.4***/***/. | 11.4***/***/. | 13.1***/./. | |

| SBP | Age-Normal | 10.5 | 10.8 | 10.7 | 11.2 |

| Regression | 9.1* | 10.1. | 9.7. | 9.9* | |

| RNN12h | 7.6***/** | 8.0***/*** | 7.4***/*** | 8.2***/*** | |

| RNNPMD | 7.4***/**/. | 7.7***/***/. | 7.3***/***/. | 8.1***/***/. | |

| DBP | Age-Normal | 11.4 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 10.3 |

| Regression | 8.2*** | 8.6** | 8.5** | 8.6** | |

| RNN12h | 7.3***/. | 7.7***/. | 7.1***/*** | 7.7***/. | |

| RNNPMD | 6.9***/**/. | 7.0***/**/. | 6.8***/***/. | 7.4***/**/. |

P-values of error comparisons to age-normal, regression, and RNN12h within the same column and vital are denoted by sequential superscripts (.: p > .05, *: p ≤ .05, **: p ≤ .01, ***: p ≤ .001) in each cell. Bold numbers indicate the lowest error metric for a given vital/PIM2 Quartile combination.

Discussion

Patients clinically determined suitable for medical discharge, yet remaining in the PICU, afforded the opportunity to observe their clinical features in their physiologically acceptable state space for discharge. In this analysis, the PASS was represented by 3 vital signs for each child, measured during their medical-to-physical discharge period. In the ICU, published age-normal values are often implied as a guide for individual patient therapy. These results demonstrate that clinicians do not wait for age normal vital signs to determine whether a child is well enough to be discharged from the ICU.

Defining PASS associated with medically acceptable discharge was the first step towards being able to quantify a patient’s deviation from it during their ICU course. The next step was determining whether the individual child’s PASS could be predicted. An age-dependent regression analysis was used to model and predict PASS values for 3 vital signs in the PICU population. The regression PASS predictions were significantly different from published age-normal values, consistent with previous studies.12–15 In addition, 2 RNN models demonstrated the ability to predict individual patient PASS values, and these predictions better approximated the child’s true PASS values compared to age-normal and regression approximations across different diagnostic categories and severities of illness.

The similarities and distinctions between the 2 RNN models, RNNPMD and RNN12h, are important for clinical application. While RNNPMD was trained to learn patient trajectories from admission to medical discharge, RNN12h learned trajectories only from the first 12 hours following PICU admission. Both models generate PASS predictions over time, but both were compared only on their 12th hour predictions. It is important that the RNN models were accurate not only in the overall PICU population, but also in distinct subpopulations, because this validates the patient-specific nature of the RNN predictions. Patients with systemic disease, such as those with Acute Respiratory Failure,30 had more deviant vital signs than those with localized disease processes such as Brain Neoplasm. Table 2 shows that heart rate differences between age-normal and true PASS values were greater for patients with Acute Respiratory Failure, Scoliosis, and Asthma than those with Brain Neoplasm and Skull Anomalies. In contrast, the errors corresponding to the regression and RNN models had smaller variations across diagnostic categories. Furthermore, the RNN’s predictions across PIM2 quartiles were consistent regardless of diagnosis. This implies that the RNNs incorporate other EMR data in distinguishing how healthy or sick a patient may be. The RNNs also outperformed age-normal and regression approximations on the subsets, which further verifies the RNN’s ability to make patient-specific assessments across patient stratifications.

The goal of this project was to define and predict patient-specific vital signs associated with medically acceptable discharge status. This extends the work of those who have reported on the physiologic status of patients during the entirety of their PICU stay2–4,9–14 by specifically characterizing individual children’s PASS. The ability to estimate a patient’s PASS within 12 hours of admission may have uses in developing machine learning approaches to clinical management of critically ill children. Quantifying the deviance of a PICU patient’s state space from a defined acceptable state, as the patient transitions from critically ill to discharge ready, can be facilitated by having more accurate determinations of the patient’s PASS vital signs or other features. The ability to posit a child’s physiologically acceptable state space shortly after ICU admission suggests potential for developing personalized monitoring of patient status, stability, and trajectory.

There are limitations to this study. Only 3 variables associated with the complete PASS were assessed, and the predictions of these variables do not necessarily represent actual targets for care. Further, PASS as defined in this study does not identify all possible acceptable state spaces, merely those observed in the study population. Complex analysis of PASS will be necessary to further define other aspects of this state space across variables and conditions. Future work will expand the predicted physiologic features of the patient’s PASS. Another limitation is that the population came from only 1 tertiary PICU. Future work will endeavor to validate these results using data from multiple collaborating sites. Lastly, the study is retrospective in nature. Longitudinal clinical trials are necessary to evaluate the impact of patient-specific PASS predictions as a clinical support and patient monitoring tool throughout the treatment process.

Conclusion

The concept of PASS encompasses a defined acceptable PICU discharge state. The quantified PASS vital signs acceptable for PICU discharge were compared to published age-normal values and predictions from age-dependent regression and RNN models. The RNN model predictions better approximate patient-specific PASS values than regression and age-normal values.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Laura P. and Leland K. Whittier Foundation.

Contributors

All listed authors contributed to the design, analysis, drafting, and approval of this work.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Competing interests None.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Yeh TS, Pollack MM, Ruttimann UE, et al. Validation of a physiologic stability index for use in critically ill infants and children. Pediatr Res 1984; 18 (5): 445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE.. The pediatric risk of mortality III—acute physiology score (PRISM III-APS): a method of assessing physiologic instability for pediatric intensive care unit patients. J Pediatr 1997; 131 (4): 575–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slater A, Shann F, Pearson G.. PIM2: a revised version of the paediatric index of mortality. Intensive Care Med 2003; 29 (2): 278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duncan H, Hutchison JS, Parshuram CS.. The pediatric early warning system score: a severity of illness score to predict urgent medical need in hospitalized children. J Crit Care 2006; 21 (3): 271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Akram AR, et al. Severity assessment tools for predicting mortality in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2010; 65 (10): 878–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lockrem J. Recommendations for intensive care unit admission and discharge criteria. Crit Care Med 1989; 17 (6): 597.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dawson J. Admission, discharge, and triage in critical care. Principles and practice. Crit Care Clin 1993; 9 (3): 555–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nates J, Nunnally M, Kleinpell R, et al. ICU admission, discharge, and triage guidelines: a framework to enhance clinical operations, development of institutional policies, and further research. Crit Care Med 2016; 44 (8): 1553–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fleming S, Thompson M, Stevens R, et al. Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years of age: a systematic review of observational studies. Lancet 2011; 377 (9770): 1011–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knudson RJ, Slatin RC, Lebowitz MD. et al. The maximal expiratory flow-volume curve. Am Rev Respir Dis 2015; 113 (5): 587–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Falkner B, Daniels S, Flynn J, et al. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2004; 114 (2 III): 555–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bonafide CP, Brady PW, Keren R, et al. Development of heart and respiratory rate percentile curves for hospitalized children. Pediatrics 2013; 131 (4): e1150.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eytan D, Goodwin AJ, Greer R, et al. Distributions and behavior of vital signs in critically ill children by admission diagnosis. Pediatr Crit Care Med2018; 19 (2): 115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eytan D, Goodwin A, Greer R, et al. Heart rate and blood pressure centile curves and distributions by age of hospitalized critically ill children. Front Pediatr 2017; 5: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Albers DJ, Elhadad N, Claassen J, et al. Estimating summary statistics for electronic health record laboratory data for use in high-throughput phenotyping algorithms. J Biomed Inform 2018; 78: 87–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aczon M, Ledbetter D, Ho LV, et al. Dynamic mortality risk predictions in pediatric critical care using recurrent neural networks. arXiv:. 2017: arXiv preprint(170106675).

- 17. Huff SM, Rocha RA, Bray BE, et al. An event model of medical information representation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1995; 2 (2): 116–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lasko T, Denny J, Levy M.. Computational phenotype discovery using unsupervised feature learning over noisy, sparse, and irregular clinical data. PLoS One 2013; 8 (6):e66341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ho LV, Ledbetter D, Aczon M, et al. The Dependence of Machine Learning on Electronic Medical Record Quality. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2017;2017:883–891. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simel D. Approach to the patient: history and physical examination. Goldmans Cecil Med 2016. 24th edition, Pages 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Behrman RE, Kligman RM, Jensen HB.. Nelson’s Textbook of Pediatrics. WB Saunders; 2000. Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J.. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput 1997; 9 (8): 1735–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shah S, Ledbetter D, Aczon M, et al. Early prediction of patient deterioration using machine learning techniques with time series data. Crit Care Med 2016; 44 (12): 87. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi E, Schuetz A, Stewart W, et al. Using recurrent neural network models for early detection of heart failure onset. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017; 24 (2): 361–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dernoncourt F, Lee J, Uzuner O, et al. De-identification of patient notes with recurrent neural networks. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017; 24 (3): 596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Razavian N, Sontag D. Temporal convolutional neural networks for diagnosis from lab tests. arXiv2015: arXiv preprint(151107938).

- 27. Greff K, Srivastana RKJ, et al. LSTM: a search space odyssey. arXiv 2015: arXiv preprint(150304069).

- 28. Cressie NA, Sheffield LJ, Whitford HJ.. Use of the one sample t-test in the real world. J Chronic Dis 1984; 37 (2): 107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hazelwood A. ICD-9-CM Diagnostic Coding and Reimbursement for Physician Services 2006 Edition American Health Information Management Association; 2005. Chicago, IL.

- 30. ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA 2012; 307 (23): 2526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.