Abstract

Objectives

Effective communication is critical to the safe delivery of care but is characterized by outdated technologies. Mobile technology has the potential to transform communication and teamwork but the evidence is currently uncertain. The objective of this systematic review was to summarize the quality and breadth of evidence for the impact of mobile technologies on communication and teamwork in hospitals.

Materials and Methods

Electronic databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, HMIC, Cochrane Library, and National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment) were searched for English language publications reporting communication- or teamwork-related outcomes from mobile technologies in the hospital setting between 2007 and 2017.

Results

We identified 38 publications originating from 30 studies. Only 11% were of high quality and none met best practice guidelines for mobile-technology-based trials. The studies reported a heterogenous range of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods outcomes. There is a lack of high-quality evidence, but nonetheless mobile technology can lead to improvements in workflow, strengthen the quality and efficiency of communication, and enhance accessibility and interteam relationships.

Discussion

This review describes the potential benefits that mobile technology can deliver and that mobile technology is ubiquitous among healthcare professionals. Crucially, it highlights the paucity of high-quality evidence for its effectiveness and identifies common barriers to widespread uptake. Limitations include the limited number of participants and a wide variability in methods and reported outcomes.

Conclusion

Evidence suggests that mobile technology has the potential to significantly improve communication and teamwork in hospital provided key organizational, technological, and security challenges are tackled and better evidence delivered.

Keywords: medical informatics, communication, hospitals, smartphone

INTRODUCTION

Effective communication between healthcare professionals within hospitals is critical to the safe delivery of care but is frequently characterized by a reliance on outdated technologies. The delivery of high-quality care inherently relies on effective communication and the inaccurate, incomplete, or delayed transfer of information can result in avoidable errors and patient harm.1–4 Failures in communication occur twice as often as those due to inadequate skill or knowledge5 and contribute to more than half of all patient safety events.3,6

Interprofessional teamwork within hospitals is complex and around the world typically relies on a mix of technologies and approaches including 1-way pagers, fixed telephones, face-to-face conversations, and newer technologies such as e-mail and smartphone messaging. Numerous problems have been highlighted with traditional pagers such as the fragmentation and burden of communication,7,8 interruptive communication behaviors,9–11 and limitations with 1-way data transfer and the supply of supporting contextual information,12,13 all of which may contribute to harmful failures of care for patients.14–16 These failings not only harm patients, but also lead to significant financial costs for healthcare providers.17

Outside of healthcare, there has been a technological revolution in handheld communication devices spawning new ways to effectively and reliably communicate, collaborate, and share information. The requirements for immediacy and accuracy of communication within healthcare, together with the potentially harmful consequences of communication failure, mean that emergent communication technologies must be studied robustly. Any change to clinical practice as a result of the deployment of new technology must be based on evidence and not on transient technology trends or individual preference. Despite this, hospital communication systems receive much less attention than other areas of healthcare innovation, and there is little robust empirical evidence on which to assess the relative advantages and disadvantages of new technologies.18 There is a careful trade-off to be made between new technologies that lead to increased complexity and cognitive overload and those that deliver meaningful improvements in communication, teamwork, and patent safety.19 The aim of this review was therefore to evaluate the current quality and breadth of evidence for the impact of mobile technologies on communication and teamwork within hospitals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This review was conducted in accordance with best practice principles as outlined in the PRISMA Statement.20 The review protocol was prospectively registered with the PROSPERO Database as per best practice guidelines (CRD42017064128).21

Search strategy and study selection

In consultation with expert medical librarians at Imperial College London, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, HMIC, the Cochrane Library, and National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment Database were searched for relevant literature published in English online or in print between January 1, 2007, and January 1, 2017. The search strategy encompassed 3 broad categories: mobile technology teamwork and communication, and the hospital setting. The search terms and strategy employed for each respective database are summarized in Supplementary AppendixTable 1 and prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria in Supplementary AppendixTable 2. This review focuses on the impact of mobile technology on communication and teamwork within real-life hospital settings. For the purposes of this review, mobile technology was defined as hand-held devices (mobiles, smartphones, tablets, or bespoke mobile devices) that facilitate 2-way communication or data transfer and which directly impact patient care. All studies evaluating the impact of mobile technologies were included, even if the intervention studied did not form part of the study protocol (eg, questionnaire studies reporting the impact of mobile technology at work in general). There were otherwise no restrictions on study design, intervention, or sample size, and both qualitative and quantitative studies were included.

Table 1.

Included studies with data for each by study design, comparator group, setting, intervention, findings, compliance with the mERA checklist, and quality assessment

| Study | Study Design | Setting and Intervention | Key Findings (communication/teamwork) | Quality Assessment22 | mERA Assessment23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventional Studies—Quantitative Outcomes | |||||

| Daruwalla et al 201425 | Prospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Poor | 6/16 |

| Duhm et al 201626 | Controlled prospective crossover study |

|

|

Fair | 6/16 |

| Gulacti et al 201627 | Retrospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Fair | 5/16 |

| Khanna et al 201528 | Pre/postobservational cohort study |

|

|

Poor | 7/16 |

| Lane et al 201229 | Pre/postobservational cohort study |

|

|

Poor | 11/16 |

| Motulsky et al 201730 | Prospective cross-sectional mixed-methods study |

|

|

Fair | 6/16 |

| Ng et al 200731 | Prospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Poor | 3/16 |

| Patel et al 201632 | Pre/postobservational cohort study |

|

|

Fair | 10/16 |

| Power et al 201433 | Prospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Fair | 5/16 |

| Przybylo et al 201434 | Controlled prospective cluster-randomized study |

|

|

Good | 10/16 |

| Smith et al 201235 | Prospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Poor | 3/16 |

| Vaisman and Wu 201736 | Retrospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Fair | 4/16 |

| Wani et al 201337 | Prospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Poor | 6/16 |

| Wu et al 201538 | Prospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Fair | 6/16 |

| Interventional Studies—Qualitative Outcomes | |||||

| Farrell 201639 | Retrospective cross-sectional interview study |

|

|

Poor | 6/16 |

| Lo et al 201240 | Retrospective cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Fair | 4/16 |

| Interventional Studies—Mixed Methods Outcomes | |||||

| Johnston et al 201541 | Prospective mixed-methods cohort study |

|

|

Fair | 8/16 |

| O’Connor et al 200942 | Prospective mixed-methods cohort study |

|

|

Good | 8/16 |

| Quan et al 201343 | Pre-/post observational cohort study |

|

|

Poor | 5/16 |

| Webb et al 201644 | Pre-/Post observational cohort study |

|

|

Fair | 6/16 |

| Wu et al 201145 | Prospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Fair | 5/16 |

| Wu et al 201346 | Prospective observational cohort study |

|

|

Fair | 5/16 |

| Noninterventional Studies—Quantitative Outcomes | |||||

| Avidan et al 201747 | Cross-sectional observational study |

|

|

Fair | |

| Ganasegeran et al 201748 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Fair | |

| Jamal et al 201649 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Fair | |

| Martin et al 201650 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Poor | |

| Menzies at al 201251 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Poor | |

| Mobasheri et al 201552 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Fair | |

| O’Connor et al 201453 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Fair | |

| Prochaska et al 201554 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Poor | |

| Wyber et al 201355 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Fair | |

| Noninterventional Studies—Qualitative Outcomes | |||||

| Hsiao and Chen 201256 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Good | |

| Scholl and Groth 201257 | Cross-sectional ethnographic study |

|

|

Good | |

| Wu et al 201458 | Cross-sectional ethnographic study |

|

|

Fair | |

| Noninterventional Studies—Mixed Methods Outcomes | |||||

| Moon and Chang 201459 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Fair | |

| Moore and Jayewardene 201460 | Cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

Poor | |

| Tran et al 201461 | Cross-sectional mixed-methods study |

|

|

Poor | |

| Wu et al 201362 | Cross-sectional ethnographic study |

|

|

Fair | |

eHR: electronic health record; MIMS: Monthly Index of Medical Specialties; mNIS: mobile nursing information system.

Table 2.

Summary of quality assessment for each study included as per National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tools22 and mERA Checklist23 compliance for each interventional study

| Study | Overall Quality Rating | mERA Checklist Criteria Compliance |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Infrastructure | 2—Technology platform | 3—Interoperability | 4—Intervention delivery | 5—Intervention content | 6—Usability | 7—User feedback | 8- Access of participants | 9—Cost assessment | 10—Adoption inputs | 11—Delivery limitations | 12—Adaptability | 13—Replicability | 14—Data security | 15—Regulatory compliance | 16—Fidelity | TOTAL | ||

| Avidan et al 201747 | Fair | |||||||||||||||||

| Daruwalla et al 201425 | Poor | X | X | – | – | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | X | – | 6/16 |

| Duhm et al 201626 | Fair | – | X | – | X | – | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | X | 6/16 |

| Farrell 201639 | Poor | – | X | – | – | X | – | X | X | X | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6/16 |

| Ganasegeran et al 201748 | Fair | |||||||||||||||||

| Gulacti et al 201627 | Fair | – | X | – | X | X | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | 5/16 |

| Hsiao and Chen 201256 | Good | |||||||||||||||||

| Jamal et al 201649 | Fair | |||||||||||||||||

| Johnston et al 201541 | Fair | X | X | – | X | X | – | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | X | – | X | 8/16 |

| Khanna et al 201528 | Poor | – | X | – | X | X | – | – | – | X | X | – | – | – | X | X | – | 7/16 |

| Lane et al 201229 | Poor | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | – | – | X | – | X | – | X | – | X | 11/16 |

| Lo et al 201240 | Fair | – | X | – | – | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4/16 |

| Martin et al 201650 | Poor | |||||||||||||||||

| Menzies at al 201251 | Poor | |||||||||||||||||

| Mobasheri et al 201552 | Fair | |||||||||||||||||

| Moon and Chang 201459 | Fair | |||||||||||||||||

| Moore and Jayewardene 201460 | Poor | |||||||||||||||||

| Motulsky et al 201730 | Fair | – | X | X | X | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | 6/16 |

| Ng et al 200731 | Poor | – | X | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3/16 |

| O’Connor et al 200942 | Good | – | X | – | X | X | – | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | X | X | X | 8/16 |

| O’Connor et al 201453 | Fair | |||||||||||||||||

| Patel et al 201632 | Fair | – | X | – | X | X | – | X | X | X | X | – | – | – | X | X | X | 10/16 |

| Power et al 201433 | Fair | – | X | – | X | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5/16 |

| Prochaska et al 201554 | Poor | |||||||||||||||||

| Przybylo et al 201434 | Good | X | X | – | X | X | – | X | X | – | X | – | – | – | X | X | X | 10/16 |

| Quan et al 201343 | Poor | – | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | X | 5/16 |

| Scholl and Groth 201257 | Good | |||||||||||||||||

| Smith et al 201235 | Poor | – | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | 3/16 |

| Tran et al 201461 | Poor | |||||||||||||||||

| Vaisman and Wu 201736 | Fair | – | X | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | 4/16 |

| Wani et al 201337 | Poor | – | X | – | X | X | – | X | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6/16 |

| Webb at al 201644 | Fair | X | X | – | X | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | 6/16 |

| Wu et al 201145 | Fair | – | X | – | X | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | 5/16 |

| Wu et al 201346 | Fair | – | X | – | – | – | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | X | 5/16 |

| Wu et al 201362 | Fair | |||||||||||||||||

| Wu et al 201458 | Fair | |||||||||||||||||

| Wu et al 201538 | Fair | – | X | X | X | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | 6/16 |

| Wyber et al 201355 | Fair | |||||||||||||||||

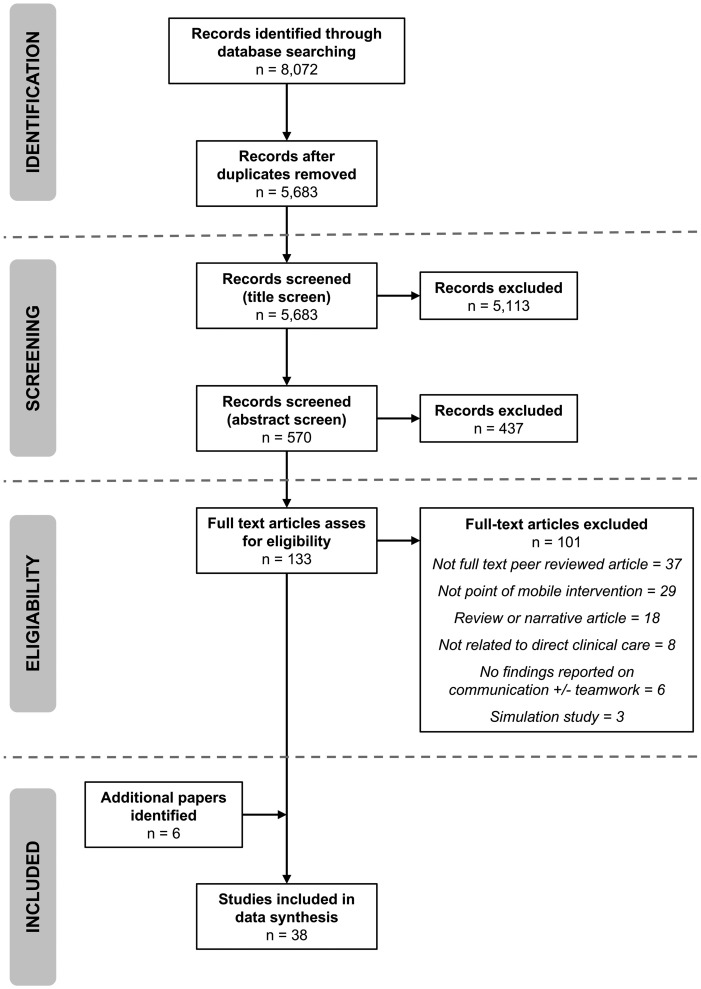

Two reviewers (GM, AK) independently reviewed all titles and abstracts for eligibility against the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria with only those papers considered relevant advanced to full text review. Cohen’s kappa agreement was calculated for each stage of screening and review with disagreements resolved through consensus. The PRISMA Diagram for study inclusion is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Diagram of study identification, screening, and inclusion.

Data extraction and quality assessment

For each study, relevant data on study design, population, intervention, comparators, outcomes, and setting were extracted. A second independent investigator reviewed this data for quality and accuracy before analysis. A quality and risk-of-bias assessment was performed for all studies according to the appropriate National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool22 with findings confirmed by consensus. A further quality assessment of each interventional study was performed by assessing compliance to the mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist.23 The mERA checklist was compiled by the World Health Organization mHealth Technical Evidence Review Group and identifies a minimum set of information that is needed to define the content, context, and technical features of an mHealth intervention and standardize the quality of evidence reporting, essentially a CONSORT24 or PRISMA20 statement for mobile technology–based interventions.

Data synthesis and analysis

The data for each study were summarized and are presented in Table 1 together with the quality assessment outcome. Studies deemed to be of poor quality are typically excluded for the purposes of analysis; however, as they formed a large number of the identified studies in this instance, they were retained. For the purposes of the analysis, studies were grouped into 6 categories: quantitative interventional studies, qualitative interventional studies, mixed-methods interventional studies, quantitative noninterventional studies, qualitative noninterventional studies, and mixed-methods noninterventional studies.

RESULTS

A total of 8 072 studies were initially identified, and following removal of duplicates a total of 5 683 eligible papers remained for screening and review. From this, we identified 38 publications from 30 unique studies as outlined in Figure 1. Included studies originated from a broad range of countries: 15 from Canada; 4 each from the United States and United Kingdom; 2 each from Singapore, Saudi Arabia and New Zealand; and a single paper arising from each of Germany, Turkey, India, Australia, Israel, Malaysia, Taiwan, Sweden, and South Korea. Inter-rater agreement for inclusion and exclusion of papers was “very good” throughout, with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.842-0.980 reported at each stage. Of note, 9 publications reported data related to the same study investigating the introduction of smartphones and web-based messaging across a small number teams within a single institution.35,36,38,43,45,46,58,61,62Table 1 summarizes the recorded data for each study. Quality assessments for all studies are summarized together with mERA Checklist compliance for the 22 interventional studies in Table 2.

Interventional studies

Description of studies

Twenty-two interventional studies—those with a specific technology deployed for the purpose of evaluation—were identified. Of these 14 reported quantitative outcomes,25–38 2 were qualitative outcomes39,40 and a further 6 were mixed-methods outcomes.41,43–46 Overall, the interventional study designs adopted were heterogeneous, with only 1 study involving any form of randomization,34 and a further single study employing a crossover study design26; all other studies otherwise took the form of uncontrolled cohort studies. The populations studied were varied, but importantly were of limited size, with the mean number of participants being only 63 (range, 8-210). Seventeen discrete interventions were available for comparison; 8 bespoke mobile applications,25,26,29,30,32,34,38,44 4 WhatsApp messenger (WhatsApp Inc, Menlo Park, CA) services,27,28,37,41 3 generic smartphones,31,33,39 and the remaining 2 interventions involved smartphones with a specific messaging or email communication functionality that were reported across multiple studies.35,36,40,43,45,46 The 14 studies reporting quantitative results utilized a range of methodologies with all but 229,36 using questionnaires, and 7 using content analysis of mobile phone data.27,30,32,35–38 Two studies used direct observational data, with one assessing the time taken to complete handover28 and the other the speed and latency of communication.29 Two further studies reported qualitative outcomes, with one using semistructured interviews and focus groups39 and the other using an exploratory case study approach.40 Six studies adopted a mixed-methods approach, with all including content analysis of messages sent or received during the study period, 4 including additional structured interviews,41,43,45,46 2 including questionnaires,42,44 and 2 including more direct observation.45,46 Overall, the quality of studies as judged through compliance with the mERA Checklist23 was poor, with a mean score of 6.1 of 16 (range, 3-11), and no study was fully compliant. The studies assessed a variety of mobile interventions with a range of cross-cutting themes being evident: improvements in workflow, efficiency, and the quality of communication; improvements in accessibility and interteam relationships; and the near universal acceptance that mobile devices should replace current methods of communication despite some key limitations being identified.

Workflow, efficiency and quality of communication

Broadly speaking, the introduction of mobile devices led to improvements in workflow, efficiency, and the quality of communication. A number of papers reported significant streamlining of clinical workflows and improvements in the quality of clinical discussion,26,34 improvements in handover and patient care,30 faster response times,33,45 and the elimination of redundant steps in vertical communication within teams.37 Significant improvements in the effectiveness of communication with greater efficiency and integration into existing workflows34 and improvements in the quality of information transfer and recall28 were also demonstrated. A further study reported that smartphones created additional value by facilitating the easy delivery of nonurgent information while also supporting the triage, prioritization, and timeliness of communication.40 Some studies looked to quantify these improvements in efficiency and timeliness with a mean response time of 2-3 minutes with mobile devices,27,38,41 and 1 study reported that >50% of email messages sent by smartphone were read in <1 minute.32 Meanwhile, the use of mobile applications led to significantly less disruption to clinical workflows,32 improvements in the speed of communication,29 and significant reductions in response times, from 5.5 to 3 minutes.44

Accessibility and interteam relationships

In addition to improved efficiency and quality of communication the use of mobile devices also had a positive impact on accessibility, interprofessional interactions, and the involvement of senior decision makers in clinical care.31,32,39 Many of the positive impacts of better communication on team relationships were highlighted in the previous section; however, improved accessibility and ease of communication can also be highly interruptive. One study identified an average of 42-51 interruptions per day and 35 minutes a day where the level of interruptions reached a potentially dangerous level.36 Other studies identified that doctors frequently felt that they were regularly interrupted with low-value and unnecessary information38 and that they were often overwhelmed by the volume of interruptions caused by their mobile device.45 A further study identified that the introduction of mobile devices led to a large increase in the number of messages sent and a subsequent 233% increase in interruptions.43 This increased communication burden may account for the 50% of messages that do not get a response.35 Increases in the communication burden may also lead to the depersonalization of the clinical team. Nurses reported feeling that mobiles negatively impact interprofessional relationships via a reduction in the face-to-face interactions that they value in helping to build relationships; conversely, doctors felt this was a positive change.45 One study reported that doctors felt the frequent interruptions they received were often inappropriate given the content and context,38 and another found interprofessional conflict due to the different subjective assessment of the urgency and priority of messages.40 A further study reported that increased messaging by nurses to seek accountability and reassurance was perceived as an attempt to absolve themselves of responsibility by doctors who felt that nurses often exaggerated the severity or urgency of a issues to illicit a response.43

Limitations and professionals’ views of mobile technology

In addition to the many positive influences reported, there were also some negative consequences of mobile devices identified. The physical limitations of mobile devices was commonly highlighted as a weakness, with small screen size, poor battery life, the requirement to enter a password on a regular basis, and unreliable connectivity all identified as limiting their effectiveness.33,39,44 In addition to their practical limitations, mobile devices were also reported to be regarded as less effective than face-to-face or direct communication for complex patient issues,38 potentially giving an unprofessional appearance if used at the bedside39 and often used inappropriately for personal non–work-related reasons.42 Despite these negative reports, there was universal agreement that the use of mobile devices acted to remove barriers to effective communication. In one study, 87% of participants wanted to continue using their devices at the end of the study period,42 while in another the majority of users stated that they would prefer to access information and communicate through a smartphone.30 A total of 85% of participants recommended the widespread use of mobiles,34 and 92% agreed that mobile applications should replace traditional pagers and there is significant potential for the greater integration of mobiles in the hospital setting.25

Noninterventional studies

Description of studies

Sixteen noninterventional studies were identified. Of these 9 reported quantitative outcomes,47–55 3 reported qualitative outcomes,56–58 and a further 4 reported mixed-methods outcomes.59–62 All 16 studies adopted a cross-sectional study design, with 11 questionnaire-based studies,48–56,59,60 3 ethnographic study designs,57,58,62 and 1 purely observational study.47 The final study used a mixed-methods approach combining direct observation, interviews, and questionnaire data.61 This group of noninterventional studies sampled a larger population with a mean number of participants of 220 (range, 25-718).

Fifteen of the studies looked to evaluate the prevalence, perception, or use of mobile technology on communication in hospitals, with a further study specifically characterizing the impact of mobile phones on interruptions in the operating theater.47 Key findings from these studies were consistent; namely, the ubiquitous use of mobile technology by healthcare professionals, the predominance of personal devices being used for work-related activity, the clear benefits that mobile-based technologies bring despite well-articulated negative consequences, the potential risks to patient confidentiality and security, and the broad support for the formal adoption of mobile technologies by healthcare institutions.

Prevalence of mobile technology in hospitals

Mobile technologies are used on a daily basis by the vast majority of healthcare professionals. Doctors use their personal devices at work more frequently than other healthcare professionals do, with up to 95% reporting regular daily use and sharing of their personal number with other members of staff50,52,55 compared with only around 50% of nurses.52,60 The messaging and email functionality of mobile devices was consistently highlighted as the principal reason for their use. One study reported that around 65% of staff use text applications,49 and another found that up to 88% use messaging or e-mails,50 and a further study found that 87% of staff use text messaging and a further 41% emails53 while at work. Indeed, 72% of staff prefer text messaging to traditional pagers, 80% cite it as their preferred method of communication,54 and 68% believe that WhatsApp is a useful adjunct to clinical practice.48 There were a number of advantages to be gained with the use of mobile communication devices, such as the ease of contact, ability to see who is calling, and reduced delays in answering.57 Another study highlighted the promotion of better information identification, integration, and interpretation and the positive impact of this on overall performance and quality.56 Further studies found mobile devices to be more convenient, less intrusive, more efficient, and less intimidating than traditional methods of communication,55 while also helping deliver better context to messages and facilitating the easy coordination of teams62 and enhancing access to information and improving decision-making.60

Negative impact of mobile technology

In addition to the benefits that mobile devices may bring, there were also a number of negative consequences identified. Studies described issues with mobile devices including the cost, lack of institutional integration and support, poor battery life, reliability, and small screen size.49,51,55 The use of mobile phones was also seen as promoting a nonprofessional image and appearing rude or impersonal when used in front of patients.55,57 One study described how the use of mobile devices depersonalizes and decontextualizes communication and introduces informal work-arounds compared with direct methods of communication such as face-to-face interactions or voice calls.58 It was also observed that mobile devices can lead to unwanted ripple effects such as disturbing nurses in the operating theater, or by increasing the unwanted contact of doctors when not at work.57 Indeed, one-third of doctors are contacted on a weekly basis, and over 1 in 5 on a daily basis when not at work.50

Patient confidentiality and data security

Importantly, a number of studies identified the potential risk to security and confidentiality of patient information with the use of personal devices.49,51,54,55,59,61 Despite these security concerns, staff favor efficiency and mobility over security,61 with only a minority performing any form of security risk assessment60 and one-third of devices not password protected.51 Crucially, 71% of staff have received54 and a further 28% regularly store confidential patient information on their personal device.52 Despite the potential negative consequences of mobile devices, the vast majority of studies found that clinical staff advocate their use and strongly support their wider deployment. One study reported that the overwhelming majority of clinical staff think mobile devices and secure messaging platforms should be integrated with current hospital systems and that existing pagers should be replaced with hospital-issued mobile phones.49,50,52

DISCUSSION

Delivering high-quality, safe healthcare is a complex endeavor requiring the careful and precise coordination of numerous professionals in the care of a single patient. This review has found that overall there is a lack of high-quality evidence evaluating the impact of mobile technologies on communication and teamwork in hospital settings. Only 11% of studies were deemed to be of high quality, no study complied with best practice guidelines for the conduct and reporting of trials involving mobile technology, and all examined small populations in restricted environments that do not truly represent complex real-world settings. Importantly, no studies sought to examine the impact on meaningful patient outcomes. Despite the relative lack of evidence, this review supports the assertion that mobile technology has the potential to significantly improve communication and teamwork within hospitals provided that concerns over the evolution of negative communication behaviors, technological flaws, and security and privacy concerns are adequately addressed and that greater evidence for safety and efficacy is delivered.

Mobile technology is ubiquitous across the world. This review has shown that these technologies are valued by healthcare staff for being more convenient and are preferred to existing modes of communication such as traditional pagers. They may act to improve and streamline clinical workflows and boost the efficiency and quality of communication. Mobile technology may also act to increase the accessibility and responsiveness of staff, improve interprofessional teamwork and relationships, and enhance access to information and better decision making. The review has also highlighted that that the negative aspects of mobile technology must be carefully considered. Clear physical and technological limitations have been identified including poor battery life, small screen size, unreliable connectivity, and the lack of consistent integration with other hospital systems. Making communication easier may result in a large increase in the communication burden that could stem from the elimination of traditional communication barriers such as the need to wait for a phone, the impersonal nature of message-based communication, and flattening of hierarchal team structures. This increased communication burden can lead to potentially harmful disruptions to care, cognitive overload, and conflict. It is crucial to align the content and purpose of a message against the process and mode of communication to mitigate against these risks.

One barrier to the adoption of mobile technology is the lack of high-quality evidence that supports the new investment hospitals need to make. It is difficult to draw clear conclusions due to methodological inadequacies including the lack of prospective randomization or assessment of matched comparator groups, the limited number of participants and truncated study lengths, and an inability to effectively pool results from multiple studies due to the substantial variability in methodologies and outcomes used. The majority of studies were based in single centers and the populations evaluated were small. Twenty-six of the studies included some form of questionnaire-based data collection yet only 630,42,49,52,56,59 discussed validity testing of the questionnaires used. While some of these methodological flaws may be put down to the inherent difficulty of assessing such interventions in complex hospital settings, few studies clearly set out to try and overcome these challenges in a meaningful way. Of the 22 interventional studies reviewed, only 226,34 had any form or randomization or prospective assessment of matched comparator groups, and in the remainder only 528,29,32,43,44 made reference to preintervention baseline data against which the mobile intervention was compared.

Despite the pervasive use of mobile technology outside of work, there are a number of diverse organizational, individual, and technological factors that are likely to impact the adoption of new communication technologies. The failure to adopt new technologies may be caused by a failure to plan for the complexity and cost, not gaining buy-in and engagement from end users or failing to appreciate that new technology changes the work, the nature of work, and who does that work.63 Additional technical, financial, legal, social, and ethical factors have also been identified that prevent the widespread uptake of new technologies.64,65 In addition to these structural factors, it has also been suggested that the extent to which mobile devices deliver value is unclear and there is a need address explicit questions about how mobile technology will deliver real benefit.66 However, it has been estimated that the use of mobile technology in healthcare has the potential to significantly improve productivity and reduce costs.67 There is a need to promote the positives of a “mobile-first” culture within healthcare organizations and provide the required leadership and resource to deliver it while being cognizant of the potential risks. This focus must come hand-in-hand with a need to target future research on understanding the broader sociotechnical aspects of new mobile technology, and how it complements and enables new pathways and processes of care to improve outcomes for patients and the working life of staff.

Concerns of privacy and security were highlighted in this review, particularly when personal mobile devices are used for the transmission of patient identifiable data. In both the United States68 and Europe69 the need to comply with stringent legislation has undoubtedly limited the deployment of smartphone-based messaging, and the use of SMS messaging for in-hospital communication has been discouraged by the Joint Commission due to security concerns.70 Improving the awareness and training of staff with regard security and privacy hand-in-hand with developing security compliant technology has the potential to greatly accelerate the uptake of new mobile technologies. Many of the negative aspects of mobile devices relate to the technology itself including poor battery life, small screen size, and lack of connectivity. To address these concerns, there is a need to design and develop technology specifically for the healthcare context and adapt work practices to alleviate some of these technological limitations. As devices become increasingly complex and data heavy, the importance of the underlying supporting infrastructure that is needed to securely and reliability store, process, and transmit huge volumes of clinical and communication data becomes increasingly important.71

CONCLUSION

Healthcare professionals use innovative mobile technology on a daily basis outside of work, yet have to cope with outdated and inadequate technology to coordinate and deliver care at work. Mobile technology can deliver very real benefits, but there is a lack of high-quality evidence, and the poor experience of institutional technology results in the development of a potentially harmful patchwork of informal workarounds and ad hoc technology adoptions. An evidence-based approach to the development, deployment and evaluation of new mobile communication devices is therefore required. To secure the “right” technology it is important to recognize and understand both the advantages and disadvantages of any particular technology and how it is used in real-world settings. Mobile technology has the potential to transform communication and teamwork in hospitals and deliver very real benefits provided a pragmatic and evidence-based approach is taken to its design, deployment and evaluation.

REGISTRATION

The review protocol was prospectively registered with the PROSPERO Database (CRD42017064128).

FUNDING

This work was supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. The funder had no role in design, analysis or interpretation of the data nor the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Imperial College London Library Services for their kind assistance and support.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ash J, Berg M, Coiera E.. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2003; 11 (2): 104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coiera E. When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2000; 7 (3): 277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sutcliffe K, Lewton E, Rosenthal M.. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med 2004; 79 (2): 186–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alvarez G, Coiera E.. Interdisciplinary communication: an uncharted source of medical error? J Crit Care 2006; 21 (3): 236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zinn C. 14,000 preventable deaths in Australian hospitals. Br Med J 1995; 310 (6993): 1487–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The Joint Commission’s sentinel event policy: ten years of improving the quality and safety of health care. Jt Comm Perspect 2005; 25 (1): 3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tipping MD, Forth VE, O'Leary KJ, et al. Where did the day go?—a time-motion study of hospitalists. J Hosp Med 2010; 5 (6): 323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel S, Lee J, Ranney D, et al. Resident workload, pager communications and quality of care. World J Surg 2010; 34 (11): 2524–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parker J, Coiera E.. Improving clinical communication: a view from psychology. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2000; 7 (5): 453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bailey B, Konstan J.. On the need for attention-aware systems: measuring effects of interruption on task performance, error rate and affective state. Comput Hum Behav 2006; 22 (4): 685–708. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Westbrook J, Woods A, Rob M, et al. Association of interruptions with increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170 (8): 683–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nguyen T, Battat A, Longhurst C, et al. Alphanumeric paging in an academic hospital setting. Am J Surg 2006; 191 (4): 561–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Espino A, Cox D, Kaplan B.. Alphanumeric paging: a potential source of problems in patient care and communication. J Surg Educ 2011; 68 (6): 447–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coiera E, Tombs V.. Communication behaviours in a hospital setting: an observational study. J Br Med 1998; 316: 673–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Westbrook JI, Coiera E, Dunsmuir WTM, et al. The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care 2010; 19 (4): 284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weigl M, Muller A, Vincent C, et al. The association of workflow interruptions and hospital doctors’ workload: a prospective observational study. BMJ Qual Saf 2012; 21 (5): 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Agarwal R, Sands D, Schneider J.. Quantifying the economic impact of communication inefficiencies in U.S. hospitals. J Healthc Manag 2010; 55 (4): 265–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu R, Tran K, Lo V, et al. Effects of clinical communication interventions in hospitals: a systematic review of information and communication technology adoptions for improved communication between clinicians. Int J Med Inform 2012; 81 (11): 723–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McElroy L, Ladner D, Holl J.. The role of technology in clinician-to-clinician communication. BMJ Qual Saf 2013; 22 (12): 981–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-anayses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151 (4): 264–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. PROSPERO—International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews 2017. Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/. Accessed Jan 29, 2018.

- 22.National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Study Quality Assessment Tools 2017. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- 23. Agarwal S, LeFevre A, Lee J, et al. ; WHO mHealth Technical Evidence Review Group. Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist. Br Med J 2016; 352: i1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schulz K, Altman D, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med 2010; 24(8):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Daruwalla Z, Wong K, Thambiah J.. The application of telemedicine in orthopedic surgery in singapore: a pilot study on a secure, mobile telehealth application and messaging platform. J Med Internet Res 2014; 2 (2): e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duhm J, Fleischmann R, Schmidt S, et al. Mobile electronic medical records promote workflow: physicians’ perspective from a survey. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016; 4 (2): e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gulacti U, Lok U, Hatipoglu S, et al. An analysis of WhatsApp usage for communication between consulting and emergency physicians. J Med Syst 2016; 40: 130. doi:10.1007/s10916-016-0483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khanna V, Sambandam S, Gul A, et al. WhatsApp”ening in orthopedic care: a concise report from a 300-bedded tertiary care teaching center. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015; 25 (5): 821–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lane J, Sandberg W, Rothman B.. Development and implementation of an integrated mobile situational awareness iPhone application VigiVU at an academic medical center. Int J CARS 2012; 7 (5): 721–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Motulsky A, Wong J, Cordeau J-P, et al. Using mobile devices for inpatient rounding and handoffs: an innovative application developed and rapidly adopted by clinicians in a pediatric hospital. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017; 24: e69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ng WH, Wang E, Ng I.. Multimedia messaging service teleradiology in the provision of emergency neurosurgery services. Surg Neurol 2007; 67 (4): 338–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patel N, Siegler J, Stromberg N, et al. Perfect Storm of inpatient communication needs and an innovative solution utilizing smartphones and secured messaging. Appl Clin Inform 2016; 7: 777–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Power J, Spina S, Forbes D, et al. Integration of smartphones into clinical pharmacy practice: an evaluation of the impact on pharmacists’ efficiency. Health Policy Technol 2014; 3 (4): 296–305. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Przybylo J, Wang A, Loftus P, et al. Smarter hospital communication: secure smartphone text messaging improves provider satisfaction and perception of efficacy, workflow. J Hosp Med 2014; 9 (9): 573–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith C, Quan S, Morra D, et al. Understanding interprofessional communication: a content analysis of email communications between doctors and nurses. Appl Clin Inform 2012; 3: 38–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vaisman A, Wu R.. Analysis of smartphone interruptions on academic general internal medicine wards. Appl Clin Inform 2017; 8: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wani S, Rabah S, AlFadil S, et al. Efficacy of communication amongst staff members at plastic and reconstructive surgery section using smartphone and mobile WhatsApp. Indian J Plast Surg 2013; 46 (3): 502–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu R, Lo V, Morra D, et al. A smartphone-enabled communication system to improve hospital communication: usage and perceptions of medical trainees and nurses on general internal medicine wards. J Hosp Med 2015; 10 (2): 83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Farrell M. Use of iPhones by Nurses in an acute care setting to improve communication and decision-making processes: qualitative analysis of nurses’ perspectives on iPhone yse. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016; 4 (2): e43.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lo V, Wu R, Morra D, et al. The use of smartphones in general and internal medicine units: a boon or a bane to the promotion of interprofessional collaboration? J Interprof Care 2012; 26 (4): 276–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Johnston MJ, King D, Arora S, et al. Smartphones let surgeons know WhatsApp: an analysis of communication in emergency surgical teams. Am J Surg 2015; 209 (1): 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O’Connor C, Friedrich J, Scales D, et al. The use of wireless e-mail to improve healthcare team communication. J Am Med Informatics Assoc 2009; 16: 705–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Quan S, Wu R, Rossos P, et al. It’s not about pager replacement: an in-depth look at the interprofessional nature of communication in healthcare. J Hosp Med 2013; 8 (3): 137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Webb C, Spina S, Young S.. Integrating smartphone communication strategy and technology into clinical practice: a mixed methods research study. Health Policy Technol 2016; 5 (4): 370–5. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu R, Rossos P, Quan S, et al. An evaluation of the use of smartphones to communicate between clinicians: a mixed-methods study. J Med Internet Res 2011; 13 (3): e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu R, Tzanetos K, Morra D, et al. Educational impact of using smartphones for clinical communication on general medicine: more global, less local. J Hosp Med 2013; 8 (7): 365–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Avidan A, Yacobi G, Weissman C, et al. Cell phone calls in the operating theater and staff distractions: an observational study. J Patient Saf 2017 Jan 9. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ganasegeran K, Renganathan P, Rashid A, et al. The m-Health revolution: exploring perceived benefits of WhatsApp use in clinical practice. Int J Med Inform 2017; 97: 145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jamal A, Temsah M-H, Khan SA, et al. Mobile phone use among medical residents: a cross-sectional multicenter survey in Saudi Arabia. J Med Internet Res. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016; 4 (2): e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Martin G, Janardhanan P, Withers T, et al. Mobile revolution: a requiem for bleeps? Postgrad Med J 2016; 92 (1091): 493–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Menzies O, Thwaites J.. A survey of personal digital assistant use in a sample of New Zealand doctors. N Z Med J 2012; 125 (1352): 48–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mobasheri M, King D, Johnston M, et al. The ownership and clinical use of smartphones by doctors and nurses in the UK: a multicentre survey study. BMJ Innov 2015; 1 (4): 174. doi:10.1136/bmjinnov-2015-000062. [Google Scholar]

- 53. O’Connor P, Byrne D, Butt M, et al. Interns and their smartphones: use for clinical practice. Postgrad Med J 2014; 90: 75–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Prochaska M, Bird A-N, Chadaga A, et al. Resident use of text messaging for patient care: ease of use or breach of privacy? JMIR Med Inform 2015; 3: e37.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wyber R, Khashram M, Donnell A, et al. The Gr8est good: use of text messages between doctors in a tertiary hospital. J Commun Healthc 2013; 6 (1): 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hsiao J, Chen R.. An investigation on task-technology fit of mobile nursing information systems for nursing performance. Comput Inform Nurs 2012; 30 (5): 265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Scholl J, Groth K.. Of organization, device and context: interruptions from mobile communication in highly specialized care. Interact Comput 2012; 24 (5): 358–73. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wu R, Appel L, Morra D, et al. Short message service or disService: Issues with text messaging in a complex medical environment. Int J Med Inform 2014; 83 (4): 278–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Moon B, Chang H.. Technology acceptance and adoption of innovative smartphone uses among hospital employees. Healthc Inform Res 2014; 20 (4): 304–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Moore S, Jayewardene D.. The use of smartphones in clinical practice. Nurs Manage 2014; 21 (4): 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tran K, Morra D, Lo V, et al. The use of smartphones on general internal medicine wards: a mixed methods study. Appl Clin Inform 2014; 5 (3): 814–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wu R, Lo V, Morra D, et al. The intended and unintended consequences of communication systems on general internal medicine inpatient care delivery: a prospective observational case study of five teaching hospitals. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013; 20 (4): 766–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wachter R. Making IT Work : Harnessing the Power of Health IT to Improve Care in England 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/550866/Wachter_Review_Accessible.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- 64. Stroetmann K, Artmann J, Dumortier J, et al. United in diversity: legal challenges on the road towards interoperable eHealth eolutions in Europe. Eur J Biomed Inform 2012; 8: 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Currie W, Seddon J.. A cross-national analysis of eHealth in the European Union: Some policy and research directions. Inf Manag 2014; 51 (6): 783–97. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Prgomet M, Georgiou A, Westbrook J.. The impact of mobile handheld technology on hospital physicians’ work practices and patient care: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009; 16 (6): 792–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Thomairy N, Mummaneni M, Alsalamah S, et al. Use of smartphones in hospitals. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2015; 34 (4): 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.US Department of Health and Human Services. Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule 1996. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/summary/. Accessed Jan 31, 2018.

- 69.Information Commissioner’s Office. Overview of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 2017. Available at: https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/data-protection-reform/overview-of-the-gdpr/. Accessed May 22, 2017.

- 70.The Joint Commission. To Text or Not to Text?2015. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/clarification_use_of_secure_text_messaging/. Accessed Jan 31, 2018.

- 71. Baig M, GholamHosseini H, Moqeem A, et al. Clinical decision support systems in hospital care using ubiquitous devices: current issues and challenges. Health Informatics J 2017. Nov 1. doi:10.1177/1460458217740722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.