Abstract

Objective

Rural public health system leaders struggle to access and use data for understanding local health inequities and to effectively allocate scarce resources to populations in need. This study sought to determine these rural public health system leaders’ data access, capacity, and training needs.

Materials and Methods

We conducted qualitative interviews across Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington with individuals expected to use population data for analysis or decision-making in rural communities. We used content analysis to identify themes.

Results

We identified 2 broad themes: (1) challenges in accessing or using data to monitor and address health disparities and (2) needs for training in data use to address health inequities. Participants faced challenges accessing or using data to address rural disparities due to (a) limited availability or access to data, (b) data quality issues, (c) limited staff with expertise and resources for analyzing data, and (d) the diversity within rural jurisdictions. Participants also expressed opportunities for filling capacity gaps through training—particularly for displaying and communicating data.

Discussion

Rural public health system leaders expressed data challenges, many of which can be aided by informatics solutions. These include interoperable, accessible, and usable tools that help capture, access, analyze, and display data to support health equity efforts in rural communities.

Conclusion

Informatics has the potential to address some of the daunting data-related challenges faced by rural public health system leaders working to enhance health equity. Future research should focus on developing informatics solutions to support data access and use in rural communities.

Keywords: public health, public health informatics, health equity, data accuracy, health impact assessment, rural health

INTRODUCTION

In the northwestern United States (US), and other states and countries, rural communities face significant health inequities compared to urban populations but are often least well-served by public health systems.1,2 The result is a striking health gap between rural and urban populations.3 In the US, people living in rural counties in Washington State are 13% more likely to die from heart disease, 33% more likely to die from intentional self-harm, and 65% more likely to die from unintentional injuries or accidents than their urban counterparts.4 Oregon and Washington have the nation’s second and third highest rates of opioid abuse, respectively5—a community burden concentrated in states with large rural areas.6 The intersection of factors such as rurality, gender, and race can exacerbate health inequities.7 For example, Alaska, a predominantly rural/frontier state, has the nation’s highest rate of interpersonal violence, affecting almost 25% of Alaskan adults; however Alaska Native women are disproportionately affected, 46% of whom have experienced violence by intimate partners.8

While data can give rural communities the power to identify health inequities and inform decision-making to allocate scarce resources that support equity, data access and use are challenging. The task of using data often falls to rural local health departments (LHDs) that work with community partners in prevention efforts. When compared to urban LHDs or state health agencies,9 employees at small LHDs have less training in using data and seldom staff epidemiologists. They also face technical challenges in obtaining, sharing, and analyzing data.10

Rural LHD leaders and their community health partners, together comprising public health systems, face further challenges in obtaining and analyzing data from marginalized populations within small rural populations. Those serving frontier jurisdictions serve areas with very small population sizes and “high geographic remoteness.”11 Working with communities to gather data from and with these small populations is challenging when there is limited capacity. Rural LHDs want to use existing data from national surveys, like the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, but these surveys often do not sufficiently sample rural areas.12 Such data collection is, thus, often insufficient for statistical analyses, monitoring trends, or identifying inequities among minority or marginalized populations.

Models exist for guiding access to and use of data to support decision-making that can support rural health equity. Researchers have developed models, such as the Performance of Routine Information System Management (PRISM) framework13 which was created for the use of “routine health information systems” in developing countries, that can be applied to rural areas of developed countries. In addition, the Public Health Activities and Services Tracking (PHAST) model was developed for “fostering greater interest in and accountability” for US LHD data collection and use.14 The PRISM and PHAST models emphasize quality data, systems that assure adequate data access, and local “capacity building” in using data for decision-making. These models suggest the potential for informatics-related solutions that would support rural public health system leaders in using data to understand and address local inequities.

The purpose of this study was to understand challenges in data use and training needs among rural LHDs and their community partners in 4 northwestern US states. This understanding is intended to inform design of informatics solutions and training to build capacity for identifying and responding to local health disparities and may guide similar efforts in other states and countries with large rural areas.

METHODS

Design, setting, timeframe, and sample

This qualitative descriptive study is part of SHARE-NW: Solutions in Health Analytics for Rural Equity across the Northwest.15 This federally-funded, 5-year, US project seeks to advance public health efforts in Washington, Oregon, Alaska, and Idaho to improve rural health equity through a better understanding of data capacity, data access, and priorities and then help to address related data and capacity needs.

We conducted interviews February–March 2018. Using purposeful sampling, we identified individuals through referrals by members of the SHARE-NW Equity Advisory Committee and a contact list that our team developed from previous projects. This list and referrals included public health system leaders across the 4 states working in rural health, health equity, and public health data. We sought individuals from the participating states holding positions in which they might be expected to use data for decision-making in rural communities and worked (a) in rural LHDs or (b) for organizations working closely with rural communities around population health. We sent invitations by email to identified individuals. Theoretical saturation was used to determine the final sample size.16 We reviewed collected data until no new themes were apparent and interviews were providing similar information. Finally, we sought trustworthiness through reviewing findings with our Equity Advisory Committee, gaining feedback via presentations to and with practice partners, maintaining a study protocol, employing strict data management and analysis processes, and comparing findings to other studies.14

Measures and procedures

Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted by 3 SHARE-NW study team members. The interviewers were trained on the interview protocol by a SHARE-NW study investigator. The study team developed the interview guide, which included open-ended questions regarding (1) perceived primary health disparities in their community, (2) how their agencies currently track and monitor disparities, (3) challenges for their agencies in accessing data on disparities, and (4) how participants communicate and display data on health disparities (Appendix A). We also included one close-ended question, asking participants to rank their training needs (high, medium, low, or no need) related to understanding and tracking health disparities. A pre-determined list of local public health system training needs in the close-ended question was based on previous research by study team members.17,18 Training topics included (a) understanding health disparities, (b) tracking and monitoring disparities, (c) analyzing disparities data, and (d) displaying disparities data. In addition, we asked if there were any other training topics not mentioned but for which they wanted training.

Participants were interviewed individually or in small groups for 30–60 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed word-for-word. Participants provided verbal consent and received no interview compensation. The University of Washington’s Human Subjects Division determined this study exempt from human subjects review.

Data analysis

We used content analysis to code transcripts and identify themes.19 Transcripts were initially reviewed by the SHARE-NW team to identify themes based on the interview guide topics. Team members then met to develop and pilot test a codebook, ultimately coming to consensus on final codes. Remaining transcripts were then coded independently after being proofread against audio recordings by a team member to clarify unclear terminology or missing words. We created queries of quotations for each code, and team members reviewed and discussed coded quotations to identify themes. Frequencies were tabulated for preferences of ranked training needs. Bi-weekly meetings were held with study investigators during which the team reviewed data and discussed analyses.

RESULTS

Of the 71 individuals recruited, we enrolled 28 (39.4%). We conducted 23 individual interviews and 2 small group interviews (n = 3 and n = 2) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (n = 28)

| Characteristics | Category | Participants (n=28) |

|---|---|---|

| States (n, %) | Washington | 11 (39.3%) |

| Idaho | 7 (25.0%) | |

| Oregon | 5 (17.9%) | |

| Alaska | 5 (17.9%) | |

| Positions (n, %) | Directors or administrators | 18 (64.3%) |

| Program managers | 6 (21.4%) | |

| Epidemiologists | 2 (7.1% | |

| Others | 2 (7.1%) | |

| Organizations (n, %) | Rural local health departments | 18 (64.3%) |

| Rural community organizations (eg, counseling and prevention services) | 4 (14.3%) | |

| Consortium, coalition, or commission (with 2 of these related to tribal health) | 3 (10.7%) | |

| Health-related associations (eg, state hospital association) | 2 (7.1%) | |

| State health department | 1 (3.6%) |

Broad themes from our analysis included (1) challenges in accessing or analyzing data to monitor and address disparities (Table 2) and (2) needs for training in data use to address health inequities (Table 3).

Table 2.

Themes and representative quotes regarding challenges in accessing or using data to monitor and address inequities among rural public health system leaders in the Northwest

| Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Limited availability or access to data | “What immediately comes to mind is our migrant farmworker community especially with their language barriers and their temporary status in our community… But, it’s really hard to get the data to know who we’re looking at other than being able to talk with our community health center—what they are seeing within the migrant communities and the communities that they serve.” (P7) |

| “We’re usually using state-level data and some county-specific data. We do have some health records we can look at. But a lot of times, this data is sent into state-level systems which we don’t have direct access to for analysis, so there’s a lot of roundabout going back up to the state and asking for our own data sets and getting them back down here to analyze again.” (P20) | |

| “The numbers are very small, so data is not readily available from any source. So, we do questionnaires, focus groups, and that kind of more direct data gathering… I guess I would be concerned that any ‘data source’ that might have numbers data, so to speak, would be somewhat irrelevant to what’s actually going on the ground here because we have our finger fairly well on the pulse of that.” (P16) | |

| “So, we go in and have conversations. Then we’re having to use anecdotal data and what people are saying or what they’re seeing and observing or experiencing… more like [an] informational interview, focus group, asking targeted questions and then capturing information about what their needs are.” (P12) | |

| Data quality issues | “Our homeless data set is in horrible condition in [rural county name]. The only data that we really get to utilize on a state level to seek funding comes from the ‘point in time’ count which is a short period of time in the winter. You literally count people who are sleeping on the streets. In [rural county name] we have a very harsh winter, so you may end up counting 12 people who are homeless when realistically we know from DHS [Department of Human Services] data…that we've got 500 people who are homeless across the year…The data that we do have isn't necessarily accurate, which means it may not be the data we want to use anyway…. That seems to be underneath most of the data we have access to.” (P17) |

| “Tribes report GPRA [Government Performance and Results Act] measures [federally], as opposed to HEDIS [Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set] statewide measures…So, when we’re working with the state it makes it hard to work. We’re working on a crosswalk for those measures, but it’s still in the process. So, just the weight of having all these different ways of reporting is very frustrating for tribes.” (P9) | |

| “There are very specific bits of information like race/ethnicity data that’s not collected in systematic ways. It makes it really hard for us to do analysis by those types of things or even economic income or economic data on clients served… there’s been an attempt at, at least within the state-collected data, so through the state systems, like the DHS [Department of Human Services] having a specific protocol in how race ethnicity data will be collected, but it hasn’t necessarily spread out into the counties yet specifically, and for sure it hasn’t spread out into the health data, so there’s always trouble in trying to really make sense of race/ethnicity data.” (P20) | |

| “We look at the national data sources that are available. They’re always a little bit untimely in the sense that they’re – like our vital stats, 2016 data [that] just came out [in 2018].” (P4) | |

| Limited staff with expertise and resources for analyzing data | “I wouldn't say that we have any organized manner to do that [collect and/or analyze data], because we just don't have the capacity in our staffing, and we don't have the knowledge of how to do that. So, it really is – we see a report that indicates there's a problem, but we don't really have any ongoing monitoring or assessment capacity to really look at it.” (P10) |

| Diversity within rural jurisdictions | “For example, with BRFSS [Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System], there are a lot of tribes and tribal areas that have sort of done tribal BRFSS-type studies to get a better feeling for their communities. But that doesn’t really work very well for us because there are 229 disparate tribes across [state].” (P1) |

| “Data is difficult with tribes. I know that sometimes tribes are very sensitive about sharing it, because it’s been used against us in the past. Then, because the populations are small and some of that is very specific to each tribe, it’s just really hard to get that information… there just isn’t capacity for many of the tribes, and again small numbers, to really help start to figure that out. And, of course, no funding. There are 29 recognized tribes in [state]…So, 29 individual sets of data and stories that go with it.” (P9) |

Table 3.

Themes and representative quotes regarding needs for training in data use to address health inequities among rural public health system leaders in the Northwest

| Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Needs for training in data use to address health inequities | “I’ve run a couple of workshops…in [state] around telling the story. And the thing is that we can have all the data – you can have a bunch of data staring you in the face, but unless you know how to communicate around that, you’re lost.” (P11) |

| “I think one of our challenges is that—as the health district—What is our mission or role in that particular situation? We’re needing to do our strategic plan and deciding: …What’s our role in dealing with an issue with health disparities? As the health district, what can I do about that? What are our roles in dealing with different social determinants of health?” (P21) | |

| “I think having the kind of training where it’s around monitoring health disparities but living in that world of knowing what you know and knowing what you don’t know and knowing what you need to hire out for I think is a really important point.” (P11) | |

| “I do a program through the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and they have County Health Rankings. The person who is the director of County Health Rankings, she did a breakout session for us and walked us through, and it was so much more robust than I realized…. I had found it helpful in the past but really didn’t realize just how applicable it could be, and I think that sort of, to be frank, hand-holding, it’s something that I might personally need.” (P15) |

Challenges in accessing and analyzing data to monitor and address disparities

Public health professionals faced multiple challenges in collecting or analyzing rural data to monitor health disparities. These challenges included (1) limited availability or access to data, (2) data quality issues, (3) limited staff with expertise and resources for analyzing data, and (4) the diversity within rural jurisdictions (Table 2).

Limited availability or access to data

In some cases, data needed to track disparities did not exist. Participants described searching for but finding no data meeting their needs. Without relevant data, participants felt their jurisdictions and communities were systematically excluded and that it was not worth it to search for data. Participants also wanted, but lacked, sub-county-level data to more precisely understand needs in specific areas.

When participants found relevant data, they were often scattered across sources including across state agencies. The added complexity of accessing data from multiple sources made it difficult to identify appropriate sources. As one participant noted, “[You] go to one data source for this type of information, but if you want the other type, then you have to go to that [other source]… you just have to go to so many sources to get each individual type of thing you’re looking for.” Some participants noted that accessible data were often in a complicated format.

Another challenge for participants was that within accessible data sets, their rural, low-population communities were represented by very small sample sizes or not at all. Samples were sometimes so small that it limited the ability to identify inequities by characteristics such as gender, race, and ethnicity or to track trends. Small samples also made it difficult to conduct statistical analyses for detecting group differences, generalizing findings, or making data-driven decisions. The issue of small numbers was described as particularly serious in tribal communities. A participant described challenges in Alaska where there are over 200 tribes which makes obtaining sufficient samples for examining data regarding each tribe extremely difficult. To overcome small numbers, some participants described supplementing quantitative data by informally gathering qualitative data through community “conversations,” especially from tribes telling “their own story that goes with the data.” However, supplementing data was difficult because of limited capacity and funding. Additionally, participants raised issues around confidentiality. When sample sizes for data were too small (ie, <50), participants were hesitant to share these data as individual identification became too easy.

Data quality issues

Concerns about data collection, curation, and management left participants also questioning the quality and reliability of available data. Data perceived as unreliable or inaccurate were often considered unusable. Participants stated that decentralized reporting systems within or across states led to data sets structured and stored in different formats, making them difficult to use. Data collected in non-standardized ways was also a concern; this included demographic information, such as race, ethnicity, or income, that was collected inconsistently across states or counties.

Outdated data sets or the lack of “real-time information” barred participants from understanding important local issues and made data timeliness a concern. This included emerging health problems related to opioid abuse or social determinants that they dealt with “every day around transportation, housing, and food insecurity… When you get into those kinds of things, then timeliness is always an issue.”

Limited staff with expertise and resources for analyzing data

Participants described having limited staff expertise and resources to collect and analyze data within LHDs and among public health partner organizations. Many staff did not have formal training regarding data collection and analysis, and there was insufficient funding for training or for hiring those with the necessary expertise. Because of limited staffing, immediate pressures took precedence over comprehensive monitoring of health issues and disparities.

Participants described strategies to address capacity and resource challenges. This included partnering with other organizations, nearby counties with more resources, state public health staff, or academic partners to create usable data products. While one participant used grant funding to hire assessment support from a nearby urban LHD, they noted, “we’ve only been able to do that [hire support] when we have grant funding.” Others described contracting out for external support. Another LHD participant described working with “a local individual who does a lot of evaluation and survey development at the state and national level.” LHDs also partnered with academic institutions or state health departments for data and analysis support for particular equity issues, such as investigating the impact of living wages or housing.

Diversity within rural jurisdictions

Diversity among rural communities impacted data usage. Variability across geographies, populations, and resources undermined comparisons of characteristics across rural counties and communities. This was particularly acute in tribal areas due to a severe lack of capacity and funding to gather and analyze data. Participants also described tribes as being understandably sensitive about sharing data given historic precedents of data being inappropriately used or used against tribal members’ interests.

Needs for training in data use to address health inequities

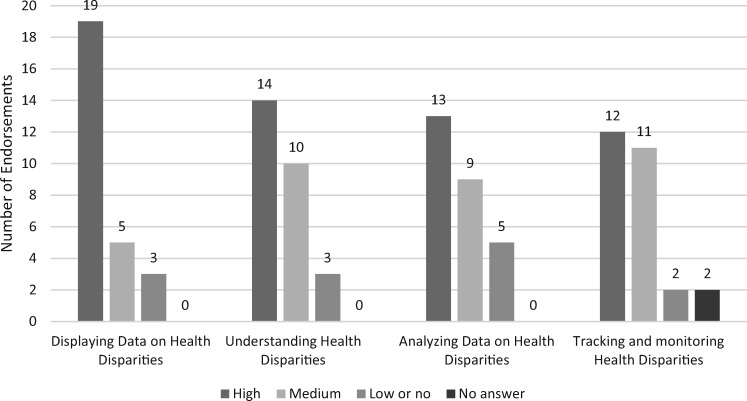

We explained to participants that a goal of SHARE-NW is to build capacity among rural public health partners for data use and decision-making to improve health and address disparities. This goal includes creating training opportunities. Our close-ended interview question listed 4 training topics being considered and asked participants to indicate preferences regarding each topic. Among the 4 topics, building capacity through training on displaying health disparities data (n = 19) had the highest preference, followed by understanding health disparities (n = 14), analyzing data on health disparities (n = 13), and tracking and monitoring health disparities (n = 12) (Figure 1). When asked to share qualitatively why they ranked “displaying data on health disparities” so highly, participants expressed the value of displaying data for decision-making internally and for communicating data to external audiences (Table 3). Visual displays of data were described as particularly important to their roles regarding (1) making “stories” more compelling to the public and policy makers and (2) engaging stakeholders on health issues.

Figure 1.

Frequencies of training needs topic priority rankings as reported by public health system leaders in Washington, Oregon, Alaska, and Idaho (n = 27*).

*A focus group of 2 individuals answered as a group instead of as individual opinions, resulting in the sum of participants here as 27 instead of the total number of 28.

Participants described “analyzing data on health disparities” and “tracking and monitoring health disparities” as helpful because their staff generally had no advanced training on these topics. Some participants described having less interest in the 4 training topics than other participants had indicated. Of these participants, 1 expressed that they had staff who could analyze data. Another participant expressed disinterest in having their agency be the entity that would analyze health disparities data; instead, they preferred another entity do this work.

Participants expressed that training on how to access data was more important than training on how to analyze it. They wanted to know how to work with multiple sources of data and have a system where information could be shared more easily across their organization and with external partners. Participants reported that having data already aggregated, analyzed, and accessible could help them and their staff with minimal analytical background to more easily use and prepare data for agency or stakeholder meetings. They also wanted to know how best to make sense of small numbers and track trends without having to aggregate data over years.

Besides training for data use itself, participants described needing training for all agency staff related to health disparities and their role in addressing them. Participants also wanted to better know how to identify health disparities, their root causes, and strategies to address them.

DISCUSSION

Understanding and addressing health inequities requires access to high-quality population data and the capacity to collect, analyze, and use data.20 We identified several issues faced by rural LHD staff and community partners that interfered with obtaining and using high-quality data for addressing health inequities. Our findings are consistent with other studies regarding data challenges among public health systems21; yet our unique focus on rural areas and health equity illuminates the depth and breadth of data challenges for rural communities. Specific challenges included severe problems with data access, availability, quality, appropriate expertise, and capacity for analysis. These challenges are particularly difficult in tribal areas due to variation across tribes, small populations, and historic injustices related to data—similar problems have been documented in rural settings outside of the US.2,22–24

Our findings also point to data and capacity issues that may underlie previous descriptive research showing that, compared to their urban counterparts, rural LHDs use a significantly smaller array of “types of health disparities-related activities” in their efforts to promote equity.21 These are issues we identified as likely to contribute to the “double disparity” that rural communities experience and that LHDs are currently ill-equipped to address.1 Lack of data access and capacity for data-informed decision-making may affect LHDs’ partnering with community organizations. Shah and colleagues, for example, found that rural LHDs, which face the greatest “information system challenges” of all US public health systems, had significantly lower odds of supporting “community efforts to change the causes of health disparities” when compared to urban agencies.20

Compared to urban settings, public health data lag far behind what is needed by LHDs to effectively serve rural populations.1 The small numbers in these communities and subpopulations exacerbate data challenges public health leaders experience—especially for tribes and tribal areas. Participants in our study, however, expressed ways in which they interact with stakeholders around data and information (formally and informally) even as they wish they had more data with which to tell the story of the health issues that they perceive. Connections with stakeholders create opportunities for taking more “community-engaged approaches” to collecting local population-level data that involve community partners gathering “granular and place-based” data through surveys, qualitative sources, and community meetings.25 Such community-engaged approaches should be designed to be responsive to desires for better data and informatics capacity to understand health and communicate health issues while also assuring sensitivity to issues of confidentiality and ethical use of data.26

In their study assessing informatics capacities of LHDs across the US, Shah and colleagues described public health as “fundamentally an information business.”27 While they did not focus on the information needed to address disparities, they identified a lack of informatics capacity among LHDs serving rural jurisdictions for which they recommended investments in “public health informatics infrastructure” and related training.27 Rural LHDs and their community partners lack the informatics resources and expertise needed to collect and analyze data. Participants described intermittently obtaining these resources or services from agencies or academic partners generally at a cost. Therefore, LHDs did not routinely or consistently monitor disparities or build local capacity to promote equity through better use of data for decision-making.

Recommendations

Previous research, using the PHAST model mentioned previously, describes “bridging the gap” to improve data access including through better data capture, improved infrastructure, visualization tools, and expanded training.17,28 We found a large gap between the generation of data and its use that is particularly troubling in rural areas. Informatics plays (or should play) a “critical role” in an LHD’s “daily operation.”27 As such, the field of health informatics has the potential (and obligation) to offer solutions to address rural public health challenges regarding accessing and using data to address inequities. Our study suggests several informatics-related recommendations.

Improved informatics infrastructure

Although not specifically raised as a need by our participants, improvements in the information and communications infrastructure would significantly address challenges we identified regarding tracking health inequities in rural communities. One improvement is the standardization of health information messaging and transfer including standardized processes for data access, collection, sharing, and management. A great deal of standardization has already been established through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Information Network and the Office of the National Coordinator. 29 LHDs could more effectively adopt Public Health Information Network data standards, for example, using existing infrastructure, tools, resources, and processes that are systematically made available to and adapted for rural communities. Information infrastructure improvements would be supported by expanding digital access within rural communities, lessening the digital divide through extensive low-cost internet access, and improving public health access to online data sets and visualization tools currently unavailable to many rural communities.30 Professional health informatics organizations, such as the American Medical Informatics Association and Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, should openly support proposed policies to provide affordable internet access for rural communities insuring the infrastructure is there for rapid communication, data sharing, and data transfer to help rural public health leaders access data and larger samples.

Informatics approaches could be applied to address working with small numbers or lack of data. This includes development and application of analytical methods that support better use of small numbers via data smoothing and Bayesian imputation techniques and protection of identification through advanced masking methods.31,32 Such methods may yield data and information made relevant to local users, yet may require training and support for LHD staff and infrastructure due to limited capacity.

Our study participants also indicated a desire for better ways to display data to educate stakeholders and support decision-making. Data visualization tools could support rural public health leaders in displaying data and telling the story of inequities while educating policy makers desirous of “high-quality information but in bite-size and readily accessible forms.”33 Visualization concepts, interventions, and technologies can also assist with understanding inequity-related trends. Current work within health data visualization and evaluation, which has mainly focused on clinical settings, could inform development of visualization tools for rural public health.34 Existing public heath visualization tools that identify equity issues, such as AIDSVu, an interactive map of HIV-related data, can help to “pinpoint disparities” in disease and support targeted resource allocation.35 SHARE-NW is currently developing visualizations to support data access and understanding for rural LHDs.

Training

Our participants described a need for informatics-related training to help them access and use data to understand and address inequities. Informatics researchers can apply adult learning strategies already integrated into patient-based educational solutions to the development of training modalities for rural public health. Trainings developed at academic centers on health equity, data analysis, and data visualization can be shared through online e-learning and tele-training/education programs, which can reach rural and frontier areas through existing training networks, such as the multi-state Regional Public Health Training Centers funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration.36 The SHARE-NW project will be working through the Northwest Regional Public Health Training Center on the development of training to support rural public health system data users to understand and address health inequities.

Limitations

Because our team is based in a single location and had limited ability to travel to various rural areas across the 4 states, we conducted telephone interviews in order to reach as many individuals across the 4 heterogeneous states as possible. While this limited the type and depth of data we could collect, telephone interviews facilitated a wide reach of perspectives from those across a large rural and frontier area. Researchers in the future could build into their funding and methods the recruitment and training of individuals within dispersed communities across large geographic areas to support ethnographic or other in-depth, in person data collection methods to obtain additional rich and contextual data. Triangulating findings across multiple methods could also add more depth of understanding.37 Our study team will expand upon these study methods in the future as we seek to build capacity for data use by collecting data in person, via online survey, and other methods.

Our study participants were from US-based agencies in the Northwest. While we recruited individuals across the 4 states, we tried but were unable to recruit individuals working within tribal jurisdictions in the Northwest. Therefore, our study’s findings are not generalizable to rural communities outside of our region and the US or to specific tribal communities. Despite these limitations, our study’s findings are congruent with other literature2,9,10 and survey data collected internally by Northwest Center for Public Health Practice14 (where this project is based). In addition, our study's Equity Advisory Committee, comprised of regional stakeholders including individuals from tribal agencies, reviewed our findings and found them resonant. We will continue to recruit individuals within tribal agencies through the lifecycle of this project.

CONCLUSION

Rural communities face numerous challenges accessing data to identify, understand, and address health inequities. In our study with rural public health system leaders, we identified barriers to using data, such as 1) lack of easy access to timely data, 2) data quality issues specific to rural and tribal communities, and 3) the inability for rural leaders to use those data. At the same time, rural public health system leaders see better use and communication about data as critical to their local efforts and desire training and support to do so. Informatics solutions can assist with addressing these barriers, including new research to help rural leaders capture, access, use, and effectively display data. SHARE-NW work will build on this study to develop informatics and training solutions to increase availability of, access to, and use of data that reflect the complex underlying social conditions impacting health in rural areas in the Northwest US. SHARE-NW will help practice leaders examine social determinants of health, public health resources, prevention services, and rural needs through identifying and responding to urgent rural practice needs for data, making data more easily accessible to public health partners, and providing training and capacity-building—allowing for system wide innovations for reducing disparities and promoting health equity.15

FUNDING

This work was funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, grant #1 CPIMP171144-01-00.

CONTRIBUTORS

BB provided oversight to this article, prepared substantial intellectual content, gave final article approval, obtained the project funding, and conceived of the project design. SP drafted substantial article content, led the study data analysis, and approved of the final manuscript. UB assisted with question development, participated in data analysis and interpretation, provided important intellectual content to this article, and approved of the final manuscript. IO and AT contributed substantially to the data analysis and interpretation, approach to data acquisition, provided important intellectual content to this article, and approved of the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the many public health and prevention practitioners who graciously gave of their time and insights for this research.

Appendix A. Interview instrument

University of Washington School of Public Health

SHARE-NW

Interview Instrument

February 9, 2018

| Name: | Date: | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Job Position/Title: | |||

| Public Health-related Agency: | Time: | ||

| Interviewer(s): | Phone Number: |

Purpose:

Identify 6 of the highest priority gaps in capacity for data-driven decision-making to address social determinants of health among at least 72 public health personnel.

Better understand health department personnel’s understanding of health disparities in their rural communities, whether and how they track health disparities in their communities, what data sources they have available, and the need to better track disparities.

Determine training needs around tracking disparities and sharing that understanding with others.

Assess current use of data visualizations in practice and dissemination among all participants who use data in their roles.

Assess how they currently visualize the data, where and to whom they are currently presenting data, and what tools are they using to present data.

Opening Script:

| Q# | QUESTION | RESPONSE |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Please tell me your role in your public health agency and how long you have been in this role. | |

| We are going to start our conversation with a few questions about health disparities in your community and the data sources you use. For clarity purposes, the definition of health disparities we are using in this work is from the CDC. Health disparities are differences in health patterns between groups of people and usually closely linked with economic or social disadvantage.(Internal Note: Health inequities refers to avoidable differences in health between groups of people.) | ||

| 2. | What are the primary health disparities in your jurisdiction? (Examples: higher rates of obesity among Alaska Native children versus non-Native children, higher rates of diabetes among low-income versus high-income adults) | |

| 3. | Are there specific social determinants that your agency that you would like to better understand through data? Examples: poverty, housing, education, civic engagement) | |

| 4. | How do you/your agency currently monitor health disparities in your community? | |

| 5. | Washington state Interviewees: What do you know about the WA Tracking Network Tools? | |

| 6. | Are there any data and data sources would you like greater access to in order to better understand the health disparities in your jurisdiction? (Examples: business inventory for identifying food deserts or wanting to look at health of LGTBQ communities but don’t have data on gender or sexual minorities) | |

| 7. | What are the challenges or barriers to accessing or using those data sources? | |

| One of the goals of SHARE-NW is to build capacity among rural practice partners for data use and data-driven decision-making to improve health and address disparities in their communities. One of the activities that we are doing is to create training. I’m going to list of some of the training topics we are considering. | ||

| 8. | I’m going to read you a list of 4 topics, and I’m interested in understanding your training needs for each topic. Please tell me, using high, medium, low, or no, if you need training in the following areas:Understanding health disparities Tracking and monitoring health disparities Analyzing data on health disparities Displaying data on health disparities | |

| 9. | Are there other topics on health disparities that you or others in your LHD need training on? | |

| 10. | Besides yourself, who in your organization works on issues involving health disparities? | |

| Data Visualization QuestionsNow I’m going to ask some questions about data visualization. Often when people use data to understand health disparities in their communities, they use graphs and charts in addition to analyzing data. Data visualization refers to figures, visuals, or graphics to display data. Examples include bar graphs, time trends or timelines, interactive displays, maps, infographics, tables, scatter plots, etc. | ||

| 11. | What types of data visualizations do you typically create in your work to display health outcomes? | |

| 12. | To what audience(s) do you typically present your health disparities data? | |

| 13. | During program implementation, are there any points where you use data visualization? | |

| 14. | What tools or software do you currently use, if any, to create these data visualizations? (Examples: Excel, PowerPoint, Tableau, GIS) | |

| 15. | What type of data visualization support or training would be most beneficial to you? | |

| Closing Questions So I have1 closing question: | ||

| 16. | Do you have any additional ideas about how to increase capacity for local health jurisdictions to use data sources or data visualization in their work? | |

Thank you for your time today. This interview is part of the SHARE-NW project to work with practice partners to help them identify, gather, and visualize data with public health leaders to more effectively address rural health disparities and achieve health equity in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska.

Our discussion today will be about your use of data sources to look at health disparities in your community, how you communicate this data to stakeholders, and what training topics would be valuable to you.

We/I would like to record today’s discussion for transcription purposes only. Your name will not be attributed to your comments. Do we/I have your permission to record our conversation for these purposes? □ Yes □ No

We/I expect this conversation will take about 30 minutes. Do you have any questions before we begin?

I really appreciate the conversation today. Thank you for your time to discuss this topic with me.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Harris JK, Beatty K, Leider JP, Knudson A, Anderson BL, Meit M.. The double disparity facing rural local health departments. Annu Rev Public Health 2016; 37 (1): 167–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davis S, Reeve C, Humphreys JS.. How good are routinely collected primary healthcare data for evaluating the effectiveness of health service provision in a remote Aboriginal community? Rural Remote Health. 2015; 15 (4): 2804.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rural Americans at Higher Risk of Death from Five Leading Causes CDC Newsroom; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p0112-rural-death-risk.html. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 4. Washington State Hospital Association. Rural Health Care: A Strategic Plan for Washington State; 2012: 1–48. http://www.wsha.org/wp-content/uploads/2012-Rural-Health-Care-Report_FINAL2_1.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 5. Matrix Global Advisors. Health Care Costs from Opioid Abuse: A State-by-State Analysis; 2015. http://drugfree.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Matrix_OpioidAbuse_040415.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 6. Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Brady JE, Havens JR, Galea S.. Understanding the rural-urban differences in nonmedical prescription opioid use and abuse in the United States. Am J Public Health 2014; 104 (2): e52–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. In: Bartlett KT, Kennedy R, eds. Feminist Legal Theory: Readings in Law and Gender 16th ed. Chicago: Taylor and Francis; 1989: 57–80.

- 8. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_report2010-a.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'Keefe KA, Shafir SC, Shoaf KI.. Local health department epidemiologic capacity: a stratified cross-sectional assessment describing the quantity, education, training, and perceived competencies of epidemiologic staff. Front Public Health 2013; 1: 64.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arrazola J, Binkin N, Israel M, et al. Assessment of epidemiology capacity in state health departments—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67 (33): 935–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Health Resources and Services Administration. Methodogy of designation of frontier and remote areas . Federal Register 2012; 77: 66471–6. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2012-11-05/pdf/2012-26938.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: Comparability of Data BRFSS 2015 BRFSS; 2016: 1–8. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2015/pdf/compare_2015.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018.

- 13. Aqil A, Lippeveld T, Hozumi D.. PRISM framework: a paradigm shift for designing, strengthening, and evaluating routine health information systems. Health Policy Plan 2009; 24 (3): 217–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lincoln YS, Guba EG.. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Northwest Center for Public Health Practice. SHARE-NW: Solutions in Health Analytics for Rural Equity across the Northwest; 2017. http://www.nwcphp.org/research/projects/current/share-nw. Accessed January 21 2017.

- 16. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018; 52 (4): 1893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bekemeier B, Park S.. Development of the PHAST model: generating standard public health services data and evidence for decision-making. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 25 (4): 428–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bekemeier B, Chen A, Kawakyu N, Yang YR.. Local public health resource allocation: limited choices and strategic decisions. Am J Prev Med 2013; 45 (6): 769–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Assarroudi A, Nabavi FH, Armat MR, Ebadi A, Vaismoradi M.. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs 2018; 23 (1): 42–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shah GH, Mase WA, Waterfield KC.. Local health departments' engagement in addressing health disparities: the effect of health informatics . J Public Health Manag Prac 2018; 25 (2): 171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang YR, Bekemeier B.. Using more activities to address health disparities: local health departments and their top executives. J Public Health Manag Prac 2013; 19 (2): 153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whitesell NR, Mousseau A, Parker M, Rasmus S, Allen J.. Promising practices for promoting health equity through rigorous intervention science with indigenous communities . Prev Sci 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harding A, Harper B, Stone D, et al. Conducting research with tribal communities: sovereignty, ethics, and data-sharing issues. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120 (1): 6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Casale M, Lane T, Sello L, Kuo C, Cluver L.. Conducting health survey research in a deep rural South African community: challenges and adaptive strategies. Health Res Policy Syst 2013; 11: 14.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Puma JE, Belansky ES, Garcia R, Scarbro S, Williford D, Marshall JA.. A community-engaged approach to collecting rural health surveillance data. J Rural Health 2017; 33 (3): 257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lightfoot N, Strasser R, Maar M, Jacklin K.. Challenges and rewards of health research in northern, rural, and remote communities. Ann Epidemiol 2008; 18 (6): 507–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shah GH, Leider JP, Castrucci BC, Williams KS, Luo H.. Characteristics of local health departments associated with implementation of electronic health records and other informatics systems. Public Health Rep 2016; 131 (2): 272–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bekemeier B, Park SE, Whitman G.. Challenges and lessons learned in promoting adoption of standardized local public health service delivery data through application of the PHAST Model. (Under review); 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PHIN Tools and Resources; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/phin/index.html. Accessed January 6, 2019.

- 30. Carlson E, Goss J. The State of the Urban/Rural Digital Divide; 2016. https://www.ntia.doc.gov/blog/2016/state-urbanrural-digital-divide. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- 31. Rudolph BA, Shah GH, Love D.. Small numbers, disclosure risk, security, and reliability issues in web-based data query systems. J Public Health Manag Prac 2006; 12 (2): 176–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zandbergen PA. Ensuring confidentiality of geocoded health data: assessing geographic masking strategies for individual-level data. Adv Med 2014; 2014: 1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Otten JJ, Cheng K, Drewnowski A.. Infographics and public policy: using data visualization to convey complex information. Health Aff 2015; 34 (11): 1901–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu DC, Manning JD, Levy-Fix G, et al. Evaluating visual analytics for health informatics applications: a systematic review from the AMIA VIS working group task force on evaluation.J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019; 26 (4): 314–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Valdiserri RO, Sullivan PS.. Data visualization promotes sound public health practice: the AIDSvu example. AIDS Educ Prev 2018; 30 (1): 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Northwest Center for Public Health Practice. Northwest Public Health Training Center; 2018. http://www.nwcphp.org/about/funding/phtc/index.html. Accessed January 6, 2019.

- 37. Yeasmin S, Rahman KF.. Triangulation research method as the tool of social science research. BUP Journal 2012; 1 (1): 154–63. [Google Scholar]