Abstract

Objective

Patient portal functionalities, such as patient–physician e-communication, can benefit patients by improving clinical outcomes. Utilization has historically been low but may have increased in recent years due to the implementation of Stage 2 Meaningful Use for electronic health records. This study has 2 objectives: 1) to compare patient portal utilization rates before Stage 2 (2011–2013) and after Stage 2 (2014–2017), and 2) to examine whether disparities in patient portal utilization attenuate after Stage 2.

Materials and Methods

We conducted an observational study using a pooled cross-sectional analysis of 2011–2017 National Health Interview Survey data (n = 254 183).

Results

The mean percent use of patient portals significantly increased from the pre-Stage 2 to the post-Stage 2 period (6.9%, 95% CI, 6.2–7.5; P < .001). Non-Hispanic Black individuals (OR 0.81, 95% CI, 0.76–0.86; P < .0001) and Hispanic individuals (OR 0.79, 95% CI, 0.74–0.84; P < .0001) have lower odds of using patient portals compared to non-Hispanic White individuals. Although we found independent effects of race/ethnicity, we did not find a statistically significant interaction between race/ethnicity and time. We found a similar level of increase in patient portal utilization from the pre- to postperiod across racial and ethnic groups.

Discussion

Health care policies such as Stage 2 Meaningful Use are likely contributing to increased patient portal utilization across all patients and helping to attenuate disparities in utilization between subgroups of patients.

Conclusion

Further research is needed to explore which patient portal functionalities are perceived as most beneficial to patients and whether patients have access to those functionalities.

Keywords: electronic health record, meaningful use, e-health, patient portal, personal health record, personal health information management

INTRODUCTION

Patient portals can provide patients with the tools necessary to participate in, manage, and coordinate their health care.1 For example, patient portals can be used by health care providers to give patients access to tools, such as online appointment scheduling, prescription refill, or patient–physician e-communication.2,3 When surveyed about patient portals, patients overwhelmingly report interest in patient portals and believe that patient portal availability is an important criterion for selecting a provider.3–8 When used consistently, patient portals can benefit patients by improving patient–provider trust, patient satisfaction, medication adherence, and clinical outcomes.9–15 Despite the benefits, patient portal utilization has been low among patients.16–20

Studies have shown that patient portal utilization is low but has increased over time. A nationally representative study from 2018 found that 63% of patients who had a medical visit within the past year did not use a patient portal.21 Although overall usage is low, several studies have demonstrated increased usage of patient portals over time. For example, 1 study found that patient–physician e-communication increased from 30% to 40% from 2013 to 2014 among patients with access to a patient portal.22 Utilization, however, varies across patient populations. Patients with lower income, lower education, Black race, Hispanic ethnicity, public or no insurance, male gender, rural residence, and older age are significantly less likely to use patient portals.16–19,21–25 Conversely, patients with a greater number of chronic conditions are significantly more likely to use patient portals.20,24 Initial studies of patient portals found that many patients lacked access to patient portals from their provider17,26–29; however, more recent studies have suggested that access may be increasing. For example, a recent study found that 52% of patients were offered access to a patient portal in 2017 compared to 42% of patients in 2014.30 Studies have not yet explored whether federal incentive programs, such as Meaningful Use, have increased access and thus utilization of patient portals.

Stage 2 Meaningful Use was an important driver for expanding patient access to patient portals. Stage 2 required eligible providers to offer patients the ability to view, download, and transmit personal health information and e-communicate with their provider through a patient portal, which is tethered to the electronic health record (EHR).31 Most of the studies examining patient portal utilization are conducted at 1 point in time or examine trends prior to the implementation of Stage 2 Meaningful Use.16–20 Therefore, it is important to conduct a more recent analysis that examines the temporal trend of patient portal use before and after Stage 2 Meaningful Use implementation. Studies have also shown that factors, such as race, ethnicity, and health insurance, influence patients’ propensity to use patient portals.16–19,23,24,32,33 However, these differences might be explained by provider EHR adoption—studies have shown that providers with a higher proportion of Black, Hispanic, or Medicaid patients are less likely to adopt EHRs.34–37 Many of these studies were conducted in the early stages of Meaningful Use implementation before incentives were available. Therefore, it is possible that Meaningful Use incentives have helped to attenuate these disparities.

OBJECTIVE

To address this literature gap, this study has 2 aims: 1) to compare patient portal utilization rates prior to Stage 2 Meaningful Use implementation (2011–2013) and after Stage 2 Meaningful Use implementation (2014–2017), and 2) to examine whether disparities in patient portal utilization attenuate after Stage 2 Meaningful Use implementation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and sample selection

Our study used the 2011–2017 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data. The NHIS is a nationwide cross–sectional household interview survey, conducted each year by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The NHIS uses a multistage area probability design to select a nationally representative sample and provides information on health status, health care services, and health behaviors of the noninstitutionalized US population.38 We merged 3 NHIS components—the adult sample file, person file, and family file—using a unique person identifier to comprise both family- and individual-level information. Our study sample included respondents who were aged 18 years or older at the time of survey. We excluded respondents with missing information on patient portal use (n = 3303), education (n = 966), employment (n = 98), health insurance (n = 766), and usual source of care (n = 2824), which accounted for 3.4% of the total sample (Supplementary MaterialTable S1). Nearly 9% of the sample (n = 15 488) had missing information on family income, so we used the Five Multiple Imputation data provided by NCHS to impute missing values from the NHIS family income questions.39 The final study sample consisted of 224 278 respondents.

Patient portal utilization

Our primary outcome was use of patient portals which included 4 binary variables: 1) filled a prescription online, 2) scheduled a medical appointment online, 3) communicated with a health care provider by email, and 4) any use of these 3 information management tools. In the NHIS, respondents were asked to answer the question “During the past 12 months, have you ever used computers for any of the following: 1) schedule an appointment with a health care provider (online medical appointment), 2) communicate with a health care provider by email (online communication), and 3) fill a prescription (online prescription refill).” The respondents were categorized as a patient portal user if any of these 3 options were selected.

Independent variables

Independent variables in our analyses included year of survey (2011–2017), age (18–44, 45–64, and 65 or greater), sex (male and female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Other), and marital status (married and unmarried). Since year 2014 was the beginning of Stage 2 Meaningful Use, we categorized 2011–2013 as the pre-Stage 2 Meaningful Use period and 2014–2017 as the post-Stage 2 Meaningful Use period. We also included the following: 1) employment status (employed and not employed), 2) education (less than high school, high school or GED, some college, bachelor’s degree, or graduate degree or higher); 3) family income (low income [Federal Poverty Level; FPL < 200%], middle income [FPL 200%–400%], and high income [FPL > 400%]); 4) census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West); 5) health insurance (private, Medicare including dual eligible, Medicaid, other public, and uninsured); 6) usual source of care (USC) (having USC and no USC); 7) number of chronic conditions (0, 1, 2, and 3 or more); and 8) number of health care visits in the past year (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4, and 5 or more).

Statistical analyses

The unadjusted association of each potential explanatory variable with patient portal use was assessed using Wald F tests. Temporal trends in patient portal use, including 3 types of patient portal tools, were tested using the Cochran-Armitage trend test. We used linear regression to calculate the difference in mean percent use of patient portals for the pre-Stage 2 Meaningful Use period and the post-Stage 2 Meaningful Use period. We conducted multivariable logistic regression models to identify independent predictors of patient portal use. We also tested for the pre- and postdifference in the association of patient portal use with race/ethnicity and health insurance type by adding interaction terms into separate models.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To account for selection probability, oversampling, and nonresponse in the survey, we used PROC SURVEY procedures and NHIS survey weights. Statistical significance was tested at P < .05. The study was deemed exempt from review by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Among the 254 183 individuals in the sample, 17.2% of respondents had used at least 1 patient portal tool during the study period (Table 1). We observed a higher proportion of patient portal users among respondents who were female (18.8% vs 14.4% male), married (20.3% vs 13.6% unmarried), aged 45–64 (19.5% vs 17.0% 18–44 vs 13.6% 65+), and non-Hispanic White (19.6% vs 12.2% non-Hispanic Black vs 10.0% Hispanic). Use of patient portals also varied among respondents with different insurance status: private insurance (22.2%), Medicare insurance (12.9%), Medicaid insurance (8.1%), other public insurance (16.9%), and no insurance (5.4%). The proportion of patient portal users increased as the number of health care visits increased (5.1% for no office visit to 24.3% for 5 or more office visits) or as the number of chronic conditions increased (15.1% for no comorbidities to 17.3% for 3 or more comorbidities).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample by Use of Patient Portal: NHIS 2011-2017

| Used Any Patient Portal Tools |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES |

NO |

|||||

| Characteristics | Total No. | No. | Row %*, (95% CI) | No. | Row %, (95% CI) | |

| Total | 224 278 | 35015 | 17.2 (16.8–17.6) | 189 263 | 82.8 (82.4–83.2) | P value |

| Survey Year | < .0001 | |||||

| 2011 | 32 064 | 3731 | 12.6 (12.0–13.1) | 28 333 | 87.4 (86.9–88.0) | |

| 2012 | 33 277 | 3751 | 12.5 (11.9–13.0) | 29 526 | 87.5 (87.0–88.1) | |

| 2013 | 33 400 | 4448 | 14.6 (14.0–15.2) | 28 952 | 85.4 (84.8–86.0) | |

| 2014 | 35 414 | 4653 | 14.7 (14.0–15.3) | 30 761 | 85.3 (84.7–86.0) | |

| 2015 | 32 386 | 5621 | 19.2 (18.4–20.0) | 26 765 | 80.8 (80.0–81.6) | |

| 2016 | 31 875 | 6607 | 21.5 (20.6–22.5) | 25 268 | 78.5 (77.5–79.4) | |

| 2017 | 25 862 | 6204 | 24.9 (23.8–26.0) | 19 658 | 75.1 (74.0–76.2) | |

| Age Group | < .0001 | |||||

| 18-44 | 94 996 | 15 643 | 17.0 (16.5–17.5) | 79 353 | 83.0 (82.5–83.5) | |

| 45-64 | 75 685 | 13 204 | 19.5 (18.9–20.0) | 62 481 | 80.5 (80.0–81.1) | |

| 65+ | 53 597 | 6168 | 13.6 (13.0–14.1) | 47 429 | 86.4 (85.9–87.0) | |

| Sex | < .0001 | |||||

| Male | 100 307 | 13 652 | 14.8 (14.3–15.2) | 86 655 | 85.2 (84.8–85.7) | |

| Female | 123 971 | 21 363 | 19.4 (18.9–19.9) | 102 608 | 80.6 (80.1–81.1) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | < .0001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 143 062 | 26 073 | 19.6 (19.1–20.1) | 116 989 | 80.4 (79.9–80.9) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 30 604 | 3239 | 12.2 (11.6–12.8) | 27 365 | 87.8 (87.2–88.4) | |

| Hispanic | 34 997 | 3063 | 10.0 (9.4–10.5) | 31 934 | 90.0 (89.5–90.6) | |

| Other | 15 615 | 2640 | 19.2 (18.0–20.5) | 12 975 | 80.8 (79.5–82.0) | |

| Marital Status | < .0001 | |||||

| Not married | 125 594 | 16 533 | 13.6 (13.2–14.1) | 109 061 | 86.4 (85.9–86.8) | |

| Married | 98 684 | 18 482 | 20.3 (19.8–20.8) | 80 202 | 79.7 (79.2–80.2) | |

| Employment | < .0001 | |||||

| Not employed | 96 547 | 11 370 | 13.3 (12.9–13.7) | 85 177 | 86.7 (86.3–87.1) | |

| Employed | 127 731 | 23 645 | 19.8 (19.2–20.3) | 104 086 | 80.2 (79.7–80.8) | |

| Education | < .0001 | |||||

| Less than High School | 32 364 | 880 | 3.3 (3.0–3.6) | 31 484 | 96.7 (96.4–97.0) | |

| High School or GED | 56 955 | 4474 | 8.9 (8.6–9.3) | 52 481 | 91.1 (90.7–91.4) | |

| Some College | 69 381 | 11 033 | 17.2 (16.7–17.7) | 58 348 | 82.8 (82.3–83.3) | |

| Bachelor’s | 41 424 | 10 807 | 27.8 (27.1–28.6) | 30 617 | 72.2 (71.4–72.9) | |

| Graduate or Higher | 24 154 | 7821 | 34.2 (33.2–35.3) | 16 333 | 65.8 (64.7–66.8) | |

| Family Income Level | < .0001 | |||||

| Low (FPL < 200%) | 89 893 | 6979 | 8.4 (8.1–8.7) | 82 914 | 91.6 (91.3–91.9) | |

| Middle (FPL 200–400) | 70 005 | 10 636 | 15.9 (15.4–16.3) | 59 369 | 84.1 (83.7–84.6) | |

| High (FPL > 400) | 64 380 | 17 400 | 27.8 (27.1–28.4) | 46 980 | 72.2 (71.6–72.9) | |

| Census Region | < .0001 | |||||

| Northeast | 36 863 | 5325 | 15.4 (14.6–16.2) | 31 538 | 84.6 (83.8–85.4) | |

| Midwest | 48 500 | 7576 | 17.2 (16.4–18.0) | 40 924 | 82.8 (82.0–83.6) | |

| South | 80 155 | 11 425 | 15.7 (14.9–16.5) | 68 730 | 84.3 (83.5–85.1) | |

| West | 58 760 | 10 689 | 21.0 (20.0–21.9) | 48 071 | 79.0 (78.1–80.0) | |

| Type of Insurance | < .0001 | |||||

| Private | 109 324 | 23 999 | 22.8 (22.2–23.3) | 85 325 | 77.2 (76.7–77.8) | |

| Medicare | 58 727 | 6729 | 13.4 (12.9–13.9) | 51 998 | 86.6 (86.1–87.1) | |

| Medicaid | 18 317 | 1442 | 8.4 (7.8–9) | 16 875 | 91.6 (91.0–92.2) | |

| Other Public | 7552 | 1260 | 17.7 (16.5–18.9) | 6292 | 82.3 (81.1–83.5) | |

| Uninsured | 30 358 | 1585 | 5.5 (5.1–5.9) | 28 773 | 94.5 (94.1–94.9) | |

| Usual Source of Care | < .0001 | |||||

| No | 31 989 | 2377 | 7.8 (7.3–8.2) | 29 612 | 92.2 (91.8–92.7) | |

| Yes | 192 289 | 32 638 | 18.8 (18.3–19.2) | 159 651 | 81.2 (80.8–81.7) | |

| Number of Visits in Past 12 Months | < .0001 | |||||

| 0 | 39 471 | 1870 | 5.1 (4.8–5.4) | 37 601 | 94.9 (94.6–95.2) | |

| 1 | 38 753 | 4759 | 13.4 (12.9–14.0) | 33 994 | 86.6 (86.0–87.1) | |

| 2 | 58 654 | 10 307 | 19.5 (18.9–20.2) | 48 347 | 80.5 (79.8–81.1) | |

| 3–4 | 46 979 | 9255 | 22.3 (21.7–23.0) | 37 724 | 77.7 (77.0–78.3) | |

| 5+ | 40 421 | 8824 | 24.3 (23.5–25.0) | 31 597 | 75.7 (75.0–76.5) | |

| Number of Comorbidities** | < .0001 | |||||

| 0 | 105 451 | 14 972 | 15.1 (14.7–15.6) | 90 479 | 84.9 (84.4–85.3) | |

| 1 | 60 790 | 10 706 | 19.8 (19.1–20.4) | 50 084 | 80.2 (79.6–80.9) | |

| 2 | 30 583 | 5306 | 20.0 (19.2–20.7) | 25 277 | 80.0 (79.3–80.8) | |

| 3+ | 27 418 | 4022 | 17.3 (16.6–18.0) | 23 396 | 82.7 (82.0–83.4) | |

Abbreviations: FPL, federal poverty level; GED, general equivalency diploma.

Percentages are weighted to be nationally representative.

Comorbidities include hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart diseases, angina, heart attack, other heart disease, stroke, emphysema, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ulcer, and any type of cancer.

Patient portal utilization

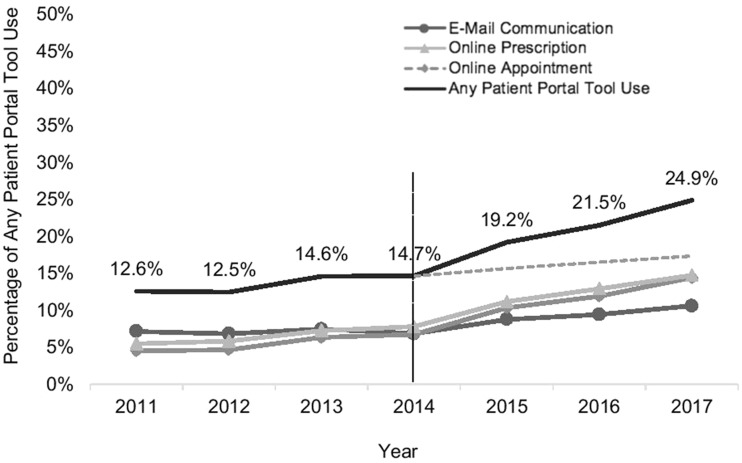

The trend analysis from 2011 to 2017 shows that the use of patient portals increased from 12.5% in 2011 to 25.0% in 2017 (Figure 1). The rate of patient portal use in 2014 (14.7%) was similar to that in 2013 (14.6%), and then begins to increase more sharply from 2015 (19.2%) through 2017 (24.9%). When comparing the difference in mean percent use of patient portals for the pre-Stage 2 Meaningful Use period and the post-Stage 2 Meaningful Use period, we observed a significant increase in any patient portal tool use (6.9%, 95% CI, 6.2–7.5; P < .001) (see Table 2). Similarly, we found a significant increase in online appointments scheduled (5.7%, 95% CI 5.2–6.2; P < .001), online patient–physician communication (5.5%, 95% CI, 5.0–5.9; P < .001), and online prescription refills (1.8%, 95% CI, 1.4–2.1; P < .001)—although the difference for this category was small relative to the other categories.

Figure 1.

Trends in Patient Portal Utilization in 2011–2017 in the US. Note. The dashed line represents the expected time trend for any patient portal tool use based on 2011–2014 (Pre-Stage 2 Meaningful Use).

Table 2.

Changes in Patient Portal Utilization between Pre- (2011–2013) and Post-Stage 2 Meaningful Use (2014–2017)

| Pre-Stage 2 MU | Post-Stage 2 MU | Absolute Difference Post vs Pre, % Change (95% CI) | Adjusted Difference Post vs Pre, % Change (95% CI)bc, | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted %, (95% CI)a | Weighted %, (95% CI)a | |||

| Scheduled medical appointment on internet | 5.2 (4.9–5.4) | 10.9 (10.5–11.3) | 5.7 (5.2–6.2) | 5.2 (4.8–5.6) |

| Communicated with health care provider by email | 6.2 (5.9–6.5) | 11.7 (11.3–12.1) | 5.5 (5.0–5.9) | 5.0 (4.6–5.4) |

| Filled a prescription on internet | 7.2 (6.9–7.4) | 8.9 (8.6–9.2) | 1.8 (1.4–2.1) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) |

| Any use of patient portal tools | 13.2 (12.8–13.6) | 20.1 (19.5–20.7) | 6.9 (6.2–7.5) | 6.0 (5.5–6.5) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; MU, Meaningful Use.

Percentages are weighted to be nationally representative.

Adjusted for all individual characteristics listed in Table 1.

All differences (both unadjusted and adjusted) in percentage changes of online appointment, email communication, prescription refill, and use of any patient portal tools are significant at P < .0001.

Multivariable analysis revealed that the likelihood of patient portal use was greater for the following binary variables: female (odds ratio [OR] 1.30, 95% CI, 1.26–1.34; P < .0001), married individuals (OR, 1.16, 95% CI, 1.12–1.20; P < .0001), employed individuals (OR, 1.13, 95% CI, 1.08–1.19; P < .0001), and individuals with a usual source of care (OR, 1.29, 95% CI, 1.20–1.37; P < .0001) (Table 3). Similarly, compared to individuals with less than a high school education, individuals with higher levels of education have higher odds of using patient portals (eg, graduate-level education: OR, 7.83, 95% CI, 7.11–8.63; P < .0001). Compared to individuals with low-income (FPL < 200%), individuals with higher levels of income have higher odds of using patient portals (eg, high income: OR, 1.87, 95% CI, 7.11–8.63; P < .0001). Compared to the West census region, individuals living in other regions have higher odds of using patient portals (eg, West: OR, 1.80, 95% CI, 1.67–1.94; P < .0001). Odds of patient portal utilization also increased as an individual’s number of chronic conditions or health visits increased. For example, individuals with 1 chronic condition (OR, 1.32, 95% CI, 1.27–1.37; P < .0001), 2 chronic conditions (OR, 1.50, 95% CI, 1.43–1.59; P < .0001), or 3 or more chronic conditions (OR, 1.53, 95% CI, 1.44–1.62; P < .0001) have higher odds of using patient portals compared to individuals with no chronic conditions.

Table 3.

Multivariable Logistic Results: Predictors of Patient Portal Use

| Any Patient Portal Tool Use |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Survey Year | ||||

| 2011 | 1.00 | |||

| 2012 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.07 | .970 |

| 2013 | 1.21 | 1.14 | 1.29 | < .0001 |

| 2014 | 1.21 | 1.13 | 1.29 | < .0001 |

| 2015 | 1.65 | 1.55 | 1.76 | < .0001 |

| 2016 | 1.94 | 1.81 | 2.09 | < .0001 |

| 2017 | 2.32 | 2.15 | 2.50 | < .0001 |

| Age Group | ||||

| 18–44 | 1.00 | |||

| 45–64 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.86 | < .0001 |

| 65+ | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.66 | < .0001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 1.30 | 1.26 | 1.34 | < .0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.00 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.86 | < .0001 |

| Hispanic | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.84 | < .0001 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.97 | .007 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Not married | 1.00 | |||

| Married | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.20 | < .0001 |

| Employment | ||||

| Not employed | 1.00 | |||

| Employed | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1.19 | < .0001 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than High School | 1.00 | |||

| High School or GED | 2.22 | 2.01 | 2.45 | < .0001 |

| Some College | 3.93 | 3.58 | 4.31 | < .0001 |

| Bachelor’s | 6.22 | 5.65 | 6.85 | < .0001 |

| Graduate or Higher | 7.83 | 7.11 | 8.63 | < .0001 |

| Family Income Level | ||||

| Low (FPL<200%) | 1.00 | |||

| Middle (FPL 200–400) | 1.31 | 1.25 | 1.38 | < .0001 |

| High (FPL>400) | 1.87 | 1.77 | 1.96 | < .0001 |

| Census Region | ||||

| Northeast | 1.00 | |||

| Midwest | 1.28 | 1.19 | 1.37 | < .0001 |

| South | 1.24 | 1.16 | 1.33 | < .0001 |

| West | 1.80 | 1.67 | 1.94 | < .0001 |

| Type of Insurance | ||||

| Private | 1.00 | |||

| Medicare | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.83 | < .0001 |

| Medicaid | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.69 | < .0001 |

| Other Public | 0.96 | 0.87 | 1.05 | 0.32 |

| Uninsured | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.68 | < .0001 |

| Usual Source of Care | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.29 | 1.20 | 1.37 | < .0001 |

| Number of Visits in Past 12 Months | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | |||

| 1 | 2.03 | 1.88 | 2.18 | < .0001 |

| 2 | 3.07 | 2.86 | 3.30 | < .0001 |

| 3–4 | 3.94 | 3.65 | 4.25 | < .0001 |

| 5+ | 4.65 | 4.31 | 5.02 | < .0001 |

| Number of Comorbidities | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | |||

| 1 | 1.32 | 1.27 | 1.37 | < .0001 |

| 2 | 1.50 | 1.43 | 1.59 | < .0001 |

| 3+ | 1.53 | 1.44 | 1.62 | < .0001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GED, general equivalency diploma.

Conversely, several factors were associated with lower odds of using patient portals. For example, compared to individuals ages 18–44, individuals 65 and older had lower odds of using patient portals (OR, 0.60, 95% CI, 0.55–0.66; P < .0001). Similarly, non-Hispanic Black individuals (OR, 0.81, 95% CI, 0.76–0.86; P < .0001) and Hispanic individuals (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.74–0.84; P < .0001) have lower odds of using patient portals compared to non-Hispanic White individuals. Compared to individuals with private insurance, individuals with Medicaid insurance (OR, 0.63, 95% CI, 0.57–0.69; P < .0001), Medicare insurance (OR, 0.76, 95% CI, 0.69–0.83; P < .0001), and no insurance (OR, 0.63, 95% CI, 0.58–0.68; P < .0001) have lower odds of using patient portals. We did not observe a statistically significant difference between private insurance and other public insurance.

Although we found independent effects of race, ethnicity, and insurance status, we did not find a statistically significant interaction between time (eg, pre-post variable) and race, ethnicity, or insurance status (Supplementary MaterialTable S2). We found a similar level of increase in patient portal utilization from the pre- to postperiod for all racial and ethnic groups and all insurance types.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the temporal trend of patient portal use and disparities in utilization before and after Stage 2 Meaningful Use implementation. The findings from this study suggest that use of patient portals has increased significantly in the past several years as providers prepared for and implemented the Stage 2 Meaningful Use program. The results also indicate that there are still disparities in patient portal utilization based on race, ethnicity, and type of insurance, but that these disparities may have attenuated after Stage 2 Meaningful Use implementation. Finally, our study revealed an unexpected finding—utilization of online prescription refill was much lower than other patient portal tools. We describe potential reasons for this below and provide recommendations for future research.

The findings suggest that patient portal utilization increased right after the implementation of the Stage 2 Meaningful Use program. The Stage 2 Meaningful Use program was implemented in stages, starting in 2014 for providers that enrolled in Stage 1 Meaningful Use in 2011 or 2012.40 Providers who enrolled in Stage 1 after 2012 were required to start Stage 2 after 2014, ranging from 2015 to 2020, depending on their enrollment date. The staged implementation of Meaningful Use may help to explain why we continue to see increases in patient portal utilization each year following 2014. Additionally, starting in 2015, eligible physicians who did not implement Meaningful Use were subjected to a payment adjustment penalty. Future studies should explore whether this trend in increased patient portal utilization continues beyond 2017, where our study ends. Stage 3 Meaningful Use also expands the requirements for patient portals, such as providing patient-specific health education resources for 35% of patients through the patient portal.40 Therefore, future studies could examine whether implementation of Stage 3 Meaningful Use increases patients’ utilization of patient portals (requirements for Stage 3 objectives will begin in 2018). There has also been recent efforts to improve patients’ access to health information across providers. For example, the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 contained provisions to encourage patients’ access to longitudinal health information aggregated from multiple providers.41 Additionally, Apple Inc. recently created the Health Records application, which would serve as a supplement to patient portals by allowing patients to aggregate health information from multiple providers.42 Future studies should explore patients’ ability to integrate health information from multiple providers’ portals.

We also observed that differences in patient portal utilization based on race, ethnicity, and insurance type may have attenuated after Stage 2 Meaningful Use implementation. Consistent with other studies, we found that non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to use a patient portal as well as individuals with Medicare or Medicaid insurance.16–19,23,24,32,33 A recent study found that Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries were less likely to use patient portals compared to privately insured individuals and were more likely to report nonuse of patient portals because of their preference for speaking directly with a provider.21 The same study found that non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to use a patient portal compared to non-Hispanic White patients and were more likely to report nonuse due to privacy concerns.21 A similar study reported patient preferences for face-to-face communication and privacy concerns as barriers to patient portal usage.30 These findings suggest that more patient education is needed to demonstrate that patient portals can be used to complement rather than replace in-person office visits.21,30

Although we observed significant differences based on race, ethnicity, and insurance type, we found that patient portal utilization increased by a similar level among all racial and ethnic groups from pre- to post-Stage 2 Meaningful Use—suggesting that racial- and insurance-based disparities may be slowly attenuating. It is possible that implementation of the Meaningful Use incentive program helped to improve EHR adoption among providers that serve a high proportion of Black, Hispanic, or Medicaid patients. A recent study found that EHR adoption disparities between providers that do and do not serve a high proportion of minority patients declined after Stage 1 Meaningful Use implementation.43 Similar studies have found that gaps in EHR adoption attenuated between providers in low- and high-poverty areas, urban and rural areas, and community health centers and physician-owned practices during the first few years following Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act implementation.44,45 Additional research is needed to evaluate how disparities in EHR adoption have changed in light of both Stage 1 and Stage 2 Meaningful Use and how changes in EHR adoption have affected patients’ use of patient portals.

Another unexpected finding in our study is that the use of some patient portal tools (eg, e-communication and online appointment scheduling) increased by 6 or 7 percentage points from the pre- to postperiod, whereas the increase for online prescription refill was smaller (2.5 percentage points). A descriptive study examining patients’ utilization of patient portals found that more patients used e-communication than online prescription refill.46 The authors suggested that providers may not offer online prescription refill as frequently as other patient portal tools if they participate in e-prescribing, wherein providers write, store, and send prescriptions to pharmacists electronically.46 Additionally, it is possible that prescription refill is implemented by the pharmacy or that not all prescriptions need a refill. Further studies are needed to explore which tools are offered within the patient portal and which tools are perceived to be most useful among patients.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. First, this study is observational and, therefore, we cannot conclude whether Stage 2 Meaningful Use was the driver of increased patient portal use over time. Second, NHIS data do not include several important factors related to patient portal utilization, such as rural residence and internet access. However, most Americans now have internet access (about 89%) due to investments by the federal government to eliminate the digital divide and increased smartphone ownership.47,48 Third, our study captures patients’ use of patient portals but does not capture providers’ adoption of patient portals. Future studies are needed to examine how providers’ adoption of patient portal has changed since Stage 2 Meaningful Use. One study reported that 47% of physicians offered patient portals in 2014 compared with 33% of physicians in 2013 suggesting an increase over time.49 Similar trends in patient portal adoption have been reported among hospitals, further evidence that access is increasing.50 Finally, there are policy changes that occurred simultaneously with Meaningful Use, such as the Affordable Care Act, making it difficult to discern whether the trends in patient portal utilization are shifting due to Meaningful Use, the Affordable Care Act, or both.

CONCLUSION

Patient portals can be used by patients to participate in, manage, and coordinate their health care. Health care policies such as Stage 2 Meaningful Use are likely contributing to increased patient portal utilization across all patients and helping to attenuate disparities in utilization between subgroups of patients. Further research is needed to explore which patient portal tools are perceived as most beneficial to patients and whether patients have access to those tools.

FUNDING

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KT conceived the research question and study design and wrote the manuscript. YRH conducted statistical analyses of the study results. SY assisted with the literature review for the manuscript. JH helped design aspects of the methodology and provided guidance on the interpretation of the analyses. AGM helped refine aspects of the study design and methodology. YHR, SY, JH, AGM reviewed and noted points of revision for the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Oh H, Rizo C, Enkin M, Jadad A.. What is eHealth (3): a systematic review of published definitions. J Med Int Res 2005; 71: e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hardiker NR, Grant MJ.. Factors that influence public engagement with eHealth: a literature review. Int J Med Inform 2011; 801: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ricciardi L, Mostashari F, Murphy J, Daniel JG, Siminerio EP.. A national action plan to support consumer engagement via e-health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 322: 376–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andreassen HK, Bujnowska-Fedak MM, Chronaki CE.. European citizens’ use of E-health services: a study of seven countries. BMC Public Health 2007; 7: 53.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pagliari C, Detmer D, Singleton P.. Potential of electronic personal health records. BMJ 2007; 3357615: 330–3. (Clinical research ed.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walker J, Ahern DK, Le LX, Delbanco T.. Insights for internists: “I want the computer to know who I am”. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 246: 727–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Archer N, Fevrier-Thomas U, Lokker C, McKibbon KA, Straus SE.. Personal health records: a scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011; 184: 515–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saparova D. Motivating, influencing, and persuading patients through personal health records: a scoping review. Perspect Health Inf Manag 2012; 9: 1f. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou YY, Kanter MH, Wang JJ, Garrido T.. Improved quality at Kaiser Permanente through e-mail between physicians and patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010; 297: 1370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fisher B, Bhavnani V, Winfield M.. How patients use access to their full health records: a qualitative study of patients in general practice. J R Soc Med 2009; 10212: 539–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Turner K, Klaman SL, Shea CM.. Personal health records for people living with HIV: a review. AIDS Care 2016; 289: 1181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McInnes DK, Shimada SL, Midboe AM, et al. Patient use of electronic prescription refill and secure messaging and its association with undetectable HIV viral load: a retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res 2017; 192: e34.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baker L, Rideout J, Gertler P, Raube K.. Effect of an internet-based system for doctor-patient communication on health care spending. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005; 125: 530–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leong SL, Gingrich D, Lewis PR, Mauger DT, George JH.. Enhancing doctor-patient communication using email: a pilot study. J Am Board Fam Pract 2005; 183: 180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Houston TK, Sands DZ, Nash BR, Ford DE.. Experiences of physicians who frequently use e-mail with patients. Health Commun 2003; 154: 515–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jung C, Padman R, Shevchik G, Paone S.. Who are portal users vs. early e-visit adopters? A preliminary analysis. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011; 2011: 1070–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beckjord EB, Finney Rutten LJ, Squiers L, et al. Use of the internet to communicate with health care providers in the United States: estimates from the 2003 and 2005 Health Information National Trends Surveys (HINTS). J Med Internet Res 2007; 93: e20.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lustria ML, Smith SA, Hinnant CC.. Exploring digital divides: an examination of eHealth technology use in health information seeking, communication and personal health information management in the USA. Health Informatics J 2011; 173: 224–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spooner KK, Salemi JL, Salihu HM, Zoorob RJ.. Disparities in perceived patient-provider communication quality in the United States: trends and correlates. Patient Educ Couns 2016; 995: 844–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bhandari N, Shi Y, Jung K.. Seeking health information online: does limited healthcare access matter? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014; 216: 1113–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anthony DL, Campos-Castillo C, Lim PS.. Who isn’t using patient portals and why? Evidence and implications from a national sample of US adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018; 3712: 1948–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patel V, Barker W, Siminerio E.. Disparities in Individuals’ Access and Use of Health IT in 2014 ONC Data Brief No. 34. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choi N. Relationship between health service use and health information technology use among older adults: analysis of the US National Health Interview Survey. J Med Internet Res 2011; 132: e33.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamin CK, Emani S, Williams DH, et al. The digital divide in adoption and use of a personal health record. Arch Intern Med 2011; 1716: 568–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Greenberg AJ, Haney D, Blake KD, Moser RP, Hesse BW.. Differences in access to and use of electronic personal health information between rural and urban residents in the United States. J Rural Health 2018; 34 (Suppl 1): s30–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bishop TF, Press MJ, Mendelsohn JL, Casalino LP.. Electronic communication improves access, but barriers to its widespread adoption remain. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 328: 1361–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Markle Foundation. Markle Survey on Health in a Networked Life 2010; 2011. https://www.markle.org/sites/default/files/20110110_HINLSurveyBrief_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brooks RG, Menachemi N.. Physicians’ use of email with patients: factors influencing electronic communication and adherence to best practices. J Med Internet Res 2006; 81: e2.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Menachemi N, Prickett CT, Brooks RG.. The use of physician-patient email: a follow-up examination of adoption and best-practice adherence 2005-2008. J Med Internet Res 2011; 131: e23.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patel V, Johnson C.. Individuals' Use of Online Medical Records and Technology for Health Needs. ONC Data Brief No. 40. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31. CMS. EHR incentive program requirements. Secondary EHR Incentive Program Requirements.2018. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/2016ProgramRequirements.html. Accessed March 25, 2019.

- 32. Jiang Y, West BT, Barton DL, Harris MR.. Acceptance and use of eHealth/mHealth applications for self-management among cancer survivors. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017; 245: 131–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aday LA, Andersen R.. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 1974; 93: 208–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. King J, Furukawa MF, Buntin MB.. Geographic variation in ambulatory electronic health record adoption: implications for underserved communities. Health Serv Res 2013; 48 (6pt1): 2037–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li C, West-Strum D.. Patient panel of underserved populations and adoption of electronic medical record systems by office-based physicians. Health Serv Res 2010; 454: 963–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hing E, Burt CW.. Are there patient disparities when electronic health records are adopted? J Health Care Poor Underserved 2009; 202: 473–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Menachemi N, Matthews MC, Ford EW, Brooks RG.. The influence of payer mix on electronic health record adoption by physicians. Health Care Manage Rev 2007; 322: 111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. NCHS. NHIS data, questionnaires and related documentation. Secondary NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation.2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm.

- 39. NCHS. Multiple Imputation of Family Income and Personal Earnings in the National Health Interview Survey: Methods and Examples. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40. CMS. EHR incentive program eligibility. Secondary EHR Incentive Program Eligibility.2016. https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/legislation/ehrincentiveprograms/eligibility.html.

- 41. Lye CT, Forman HP, Daniel JG, Krumholz HM.. The 21st century cures act and electronic health records one year later: will patients see the benefits? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 259: 1218–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Apple Inc. Empower your patients with health records on their phone. 2018. https://www.apple.com/healthcare/health-records/.

- 43. Jones EB, Furukawa MF.. Adoption and use of electronic health records among federally qualified health centers grew substantially during 2010-12. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014; 337: 1254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hsiao CJ, Jha AK, King J, Patel V, Furukawa MF, Mostashari F.. Office-based physicians are responding to incentives and assistance by adopting and using electronic health records. Health Affairs 2013; 328: 1470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Furukawa M, King J, Patel V, Hsiao C, Adler-Milstein J, Jha A.. Despite substantial progress in EHR adoption, health information exchange and patient engagement remain low in office settings. Health Affairs 2014; 339: 1672–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Riippa I, Linna M, Rönkkö I, Kröger V.. Use of an electronic patient portal among the chronically ill: an observational study. J Med Internet Res 2014; 1612: e275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. FCC. Universal service. 2018. https://www.fcc.gov/general/universal-service.

- 48. Pew Foundation. Mobile phone ownership. 2018. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/.

- 49. Heisey-Grove D, Patel V, Searcy T.. Physician Electronic Exchange of Patient Health Information. ONC Data Brief No. 31. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Henry J, Pylypchuk Y, Patel V.. Electronic Capabilities for Patient Engagement among US Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals: 2012-2015. ONC Data Brief No. 38. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT; 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.