Abstract

Objective

The study sought to develop and evaluate an electronic health record–based child abuse clinical decision support system in 2 general emergency departments.

Materials and Methods

A combination of a child abuse screen, natural language processing, physician orders, and discharge diagnoses were used to identify children <2 years of age with injuries suspicious for physical abuse. Providers received an alert and were referred to a physical abuse order set whenever a child triggered the system. Physician compliance with clinical guidelines was compared before and during the intervention.

Results

A total of 242 children triggered the system, 86 during the preintervention and 156 during the intervention. The number of children identified with suspicious injuries increased 4-fold during the intervention (P < .001). Compliance was 70% (7 of 10) in the preintervention period vs 50% (22 of 44) in the intervention, a change that was not statistically different (P = .55). Fifty-two percent of providers said that receiving the alert changed their clinical decision making. There was no relationship between compliance and provider or patient demographics.

Conclusions

A multifaceted child abuse clinical decision support system resulted in a marked increase in the number of young children identified as having injuries suspicious for physical abuse in 2 general emergency departments. Compliance with published guidelines did not change; we hypothesize that this is related to the increased number of children identified with suspicious, but less serious injuries. These injuries were likely missed preintervention. Tracking compliance with guidelines over time will be important to assess whether compliance increases as physician comfort with evaluation of suspected physical abuse in young children improves.

Keywords: electronic health record, pediatric, child maltreatment

INTRODUCTION

Child maltreatment is a leading cause of death and disability in children. In the United States, over 3 million reports are made to Child Protective Services annually. In 2016, 1750 children died from maltreatment, and close to 800 were due to physical abuse.1 Failure to recognize abuse in less severe forms may result in repeated abuse and increased morbidity and mortality.2–6 Many children with abusive injuries had been previously evaluated by a physician who did not recognize the abuse.2–8

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed guidelines related to which children should be screened for physical abuse and with which tests.9–11 Despite these guidelines, physicians do not consistently screen for physical abuse, even in high-risk situations.12,13 Studies have shown disparities in screening related to patient2,12–18 and hospital characteristics.19 While black and hispanic children with public insurance are more likely to be screened than are white children with private insurance, when white children with private insurance are screened, they are more likely to be diagnosed with abuse, suggesting screening bias.17 Nonpediatric hospitals have lower rates of screening and diagnosing abuse than pediatric hospitals do. Hospital type (general vs pediatric) is also associated with large variations in the frequency of diagnosis of child abuse, with marked underdiagnosis of abuse in general hospitals.12 The annual volume of young, injured children in a general hospital is was associated with the probability of performing a skeletal survey, a critically important disparity because most children in the United States are evaluated at general, not pediatric, hospitals.12

Experiences outside the field of child abuse have demonstrated that clinical guidelines alone are insufficient to standardize care and improve quality of care on a long-term basis.20–22 Emerging literature demonstrates that the electronic health record (EHR) can be used to improve screening rates in a wide variety of diseases, resulting in earlier intervention, decreased disparities and improved outcomes.23–26

We have previously reported on the development, validation, and evaluation of an EHR-based child abuse clinical decision support system (CA-CDSS) at UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh (CHP), a pediatric level I trauma center.27,28 The current study was designed to evaluate whether a similar CA-CDSS could be developed in 2 general EDs with a similar, but not identical, EHR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

The study took place in the emergency departments (EDs) at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy, 2 of the 13 general EDs in the UPMC Hospital system. UPMC Mercy is in the city of Pittsburgh and has a pediatric burn unit. UPMC Hamot, a level II trauma center, is in Erie, Pennsylvania, about 2 hours from Pittsburgh. They are both urban teaching hospitals staffed by general ED physicians.

Cerner Millennium® (Cerner Corporation, Kansas, MO) is the EHR used in both EDs. The Cerner platform and all forms at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy are different from CHP where the first CA-CDSS was developed.

Subjects

Subjects were children under 2 years of age evaluated in the UPMC Hamot or UPMC Mercy EDs who triggered the EHR-based alert system. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pittsburgh (for UPMC Mercy) and UPMC Hamot. A waiver of informed consent was approved.

Embedding of triggers into the EHR

In contrast to the Cerner platform at CHP, where discrete fields triggered the alert system, the Cerner platform at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy does not use discrete fields for chief complaint or nursing documentation of the physical exam. Instead, we used natural language processing (NLP) to identify words within the “focused assessment” and “chief complaint” fields to trigger the alert system. We also used specific orders and discharge diagnoses and responses to the physical abuse-focused questions within child abuse screen which is used at all both UPMC Hamot and Mercy.29 The triggers are seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Triggers embedded into the EHR at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy

| Form name/who completes the form | Name and value of field which results in a trigger when combined with patient age | Age requirement for triggering | Criteria which prevents activation of the child abuse alert system | First trigger |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child abuse screening form/RN | “Are any of the following findings present on physical examination? In a non-mobile child – ANY bruise, burn, subconjunctival hemorrhage, or frenulum injury. In a mobile child – Bruises, burns or other markings in the shape of an object; or Bruises on non-bony prominences/protected regions (eg, torso, genitalia/buttocks, upper arms, ear, neck); or More bruises than you would expect to see in even an active child.” with “yes” response (Q3) | <2 y | NA | 16 (10) |

| Child abuse screening form/RN | “Are you concerned that the history may not be consistent with the injury or illness” with a “yes” response (Q2) | <2 y | NA | 13 (8) |

| ED Assessment Form v2: Focused assessment of complaint; Chief complaint/RN | Any of the following words in a CC or focused assessment for a child <12 months of age: assault, abuse, bruis, burn, not moving, fracture, fx, broke, injury, sprain, deformity, subconjunctival hemorrhage, petechiae, arrest, hematom, ecc, echy, OR contus | <1 y (<6 mo for “injury”) | Do not trigger if trigger word is preceded by denie, no, or not; if Burn is preceded by Dr; if cord precedes fall or fell; if broke is followed by out, English, or or; if fever precedes broke | 54 (35) |

| ED Assessment Form v2: Chief complaint; focused assessment/RN | Any of the following words in a child <6 months of age: “fall,” “fell” | <6 mo | Do not trigger if Fall or Fell is followed by asleep do not trigger on fallot | 28 (18) |

| Orders/MD | Order for bone survey infant x-ray, bone survey limited x-ray or bone survey x-ray | <2 y | NA | 14 (9) |

| Orders/MD | Order for x-ray of clavicle, foot, finger, hand, knee, femur, tibia, fibula, wrist, ankle, skull, elbow, humerus, shoulder, skeletal, or extremity | <1 y | NA | 7 (4) |

| Discharge/MD | DC instruction title of abuse, fracture, injury, injuries, burn, cast, contusion, clavicle, dislocation, subluxation, hematoma, hyphema, nursemaid, hemorrhage, or bruise | <1 y | Do not trigger is if inj is preceded by head | 13 (8) |

| Discharge/MD | DC diagnosis of “contus” | <1 y | 8 (5) | |

| Discharge/MD | DC instruction of child abuse, abuse and neglect, jaw fracture, nose fracture, sternum fracture, or rib fracture | <2 y | NA | 1 (1) |

| Discharge/MD | Follow up in depart with clinic or office that has ortho, plastic, burn trauma (to pick up Burn Trauma Center-UPMC Mercy; Children's Hospital Orthopedic Clinic; CHP Orthopedics; CHP Plastics Department; Hamot Orthopedic Clinic; Hamot Orthopedic Hand; Hamot Orthopedics) | <1 y | NA | 2 (1) |

Values are n (%).

CA-CDSS: child abuse clinical decision support system; CHP: Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; DC: discharge; ED: emergency department; EHR: electronic health record; MD: medical doctor; NA: not applicable; RN: registered nurse; UPMC: University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Design

A pre-post design analysis was performed. An 8.3-month preintervention period ran from September 29, 2015, to May 10, 2016. During this time, research staff could see which providers (physician or advanced practice providers [APPs]) would have received alerts if the system were live, but there was no impact on clinical care. The preintervention period was used to resolve coding or information technology errors, evaluate the NLP system, develop the pop-up alert and physical abuse order set and assess preintervention compliance with AAP guidelines.

During the preintervention period, all NLP triggers were evaluated to determine whether they were overtriggers and coding was adjusted to correct for overtriggers. Almost all criteria that prevent activation of the CA-CDSS listed in Table 1 were developed based on the NLP evaluation. For example, the word fell in the chief complaint of a child <6 months of age was initially coded as an NLP trigger. During the preintervention period, we recognized that infants who “fell asleep” would trigger; the code was corrected to account for this. Once all the NLP corrections were made at the end of the preintervention period, we ran a final report and used that data as our preintervention data.

The preintervention period was followed by an 8.6-month intervention from May 11, 2016, to January 31, 2017. During the intervention period, when a patient triggered the alert system, a light bulb icon appeared on the tracking board (Figure 1) and the provider (physician or APP) received a pop-up alert (Figure 2), which suggested using the physical abuse order set (Figure 3A and B). The provider had to acknowledge the pop-up alert; each provider received the alert once per patient at the time they opened the chart. The physical abuse order set at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy is different from the one at CHP because of differences in the capacity of the hospitals to evaluate and treat pediatric patients and the training and experience of the providers as it relates to child abuse. A comparison of the CA-CDSS at CHP and UPMC Hamot/UPMC Mercy is shown in Table 2.

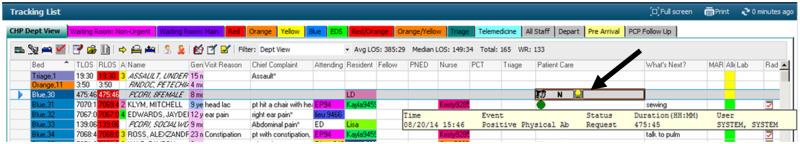

Figure 1.

The lightbulb icon on the emergency department tracking board that appears when a patient has triggered the child abuse clinical decision support system. The information in the figure is from the Cerner development domain. There are no patient data in the figure.

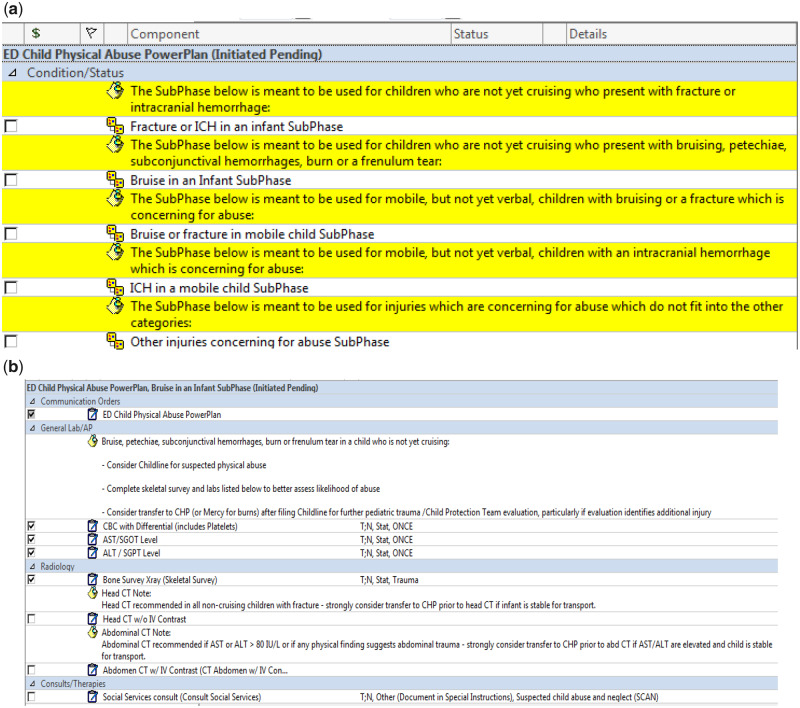

Figure 2.

Pop-up alert received by providers when a child triggered the child abuse clinical decision support system.

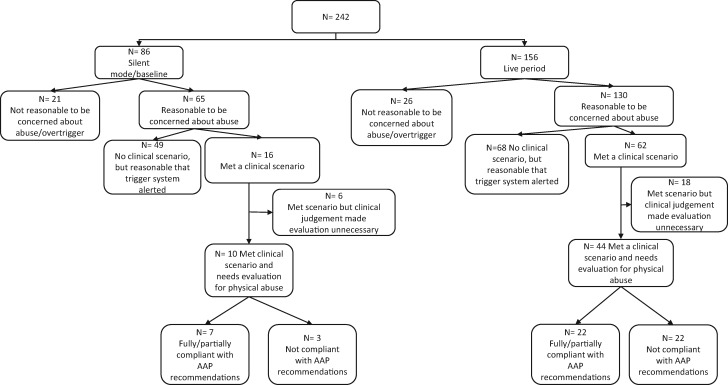

Figure 3.

(A) The initial screen of physical abuse power plan. The provider needs to select the appropriate subphase. (B) A sample subphase: “Bruise in an infant.”

Table 2.

Comparison of CA-CDSS at CHP vs UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy

| CA-CDSS at CHP | CA-CDSS at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy | |

|---|---|---|

| Study period | Baseline 10/21/14-4/6/15 | Preintervention 9/29/15-5/10/16 |

| RCT 4/8/15-11/10/15 | Intervention 5/11/16-1/31/17 | |

| Use of a universal child abuse screen | No | Yes |

| Use of natural language processing | No | Yes |

| Use of discrete fields in nursing documentation | Yes | No |

| Pop-up alerts to providers | Yes; provider continue to receive alerts until a physical abuse order set is used or until provider selects option to stop alerts | Yes, 1 alert per provider |

| Provider response to the alert | Provider has 3 options to respond to alert to see the physical abuse order set– | Provider can only acknowledge the alert |

| Yes, see the physical abuse order set | ||

| Not now (“snooze” the alert until chart is opened again | ||

| No, never see the order set (extinguish further alerts) | ||

| Physical abuse specific order sets | Yes | Yes |

| Does the alert link provider directly to the order set? | Yes | No |

CA-CDSS: child abuse clinical decision support system; EHR: electronic health record; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RN: registered nurse; UPMC: University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

In both CA-CDSS, tests recommended by the AAP guidelines are prechecked in the order set. Tests that are scenario specific are preceded by a note that describes the circumstance under which it is recommended. The order sets are specific to ED evaluation of suspected physical abuse and do not include testing, which would be conducted after admission or for other types of abuse or neglect.

End-user education and feedback

Before the start of the intervention period, attending physicians and APPs at both hospitals received communication from their respective ED directors about the introduction of the CA-CDSS. The communication included an explanation of the CA-CDSS and screen shots of the alert and order sets. The nurses had all been trained previously in how complete the child abuse screen.

Three months after the start of the intervention period, each physician and APP at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy was emailed an anonymous survey using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT), a web-based survey service. The survey was designed both to educate providers about the CA-CDSS and obtain feedback. The survey asked providers about their knowledge of the components of the CA-CDSS, whether it altered clinical decision making, and whether they felt they needed more education about the CA-CDSS. The survey was considered exempt by both Institutional Review Boards.

Throughout the intervention period, individual providers received feedback and education from the site principal investigator if they did not assess for physical abuse in situations in which it was necessary (eg, 2-month old with a bruise) or if they did not use the order set when it should have been used.

Data collection

Subject-specific data: The following data were downloaded directly from the EHR for all children who triggered the CA-CDSS: facility (UPMC Hamot or UPMC Mercy), date of ED visit, medical record number, age, race, sex, zip code, insurance (private, public, none), and the trigger that activated the alert system. Race was assigned by the registrar using a drop-down menu and analyzed as a dichotomous variable (Caucasian, not Caucasian).

Physician-specific data: Race, sex, and the number of years in practice since completion of residency were collected for all ED attendings.

Outcome measures: Each ED record was reviewed to evaluate for 3 measures: whether it was reasonable for the physician or APP to be concerned about physical abuse as defined previously,28 whether the child’s injury fit into 1 of the clinical scenarios being evaluated (Table 3), and whether the attending physician was compliant with AAP guidelines in these specific scenarios. It was considered reasonable to be concerned about physical abuse in any of the following situations: the patient had an injury that should result in screening for physical abuse based on the AAP guidelines, the patient had a nonspecific symptom known to be associated with child abuse, the patient was the sibling of a child with suspected physical abuse, the patient was involved in an incident of domestic violence, the patient had previously been a victim of abuse, an adult raised concerns for abuse, the patient died unexpectedly, or there was a misassessment by a medical professional that raised concern for abuse (eg, nurse believed an infant had a bruise that was actually a birthmark). The clinical scenarios being evaluated represent only a subset of the situations in which it would be reasonable for a physician to evaluate for abuse, but are the ones for which there are clear AAP guidelines.

Table 3.

American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for evaluation of children under 2 years of age with injuries concerning for physical abuse

| Clinical scenario | American Academy of Pediatrics recommended evaluation |

|---|---|

| Noncruising infant <12 mo of age with a fracture(s) | Skeletal survey, CBC/platelets, AST/ALT |

| Infant <6 mo of age with bruise(s) | Skeletal survey, neuroimaging (CT or MRI), CBC/platelets, PT/PTT, von Willebrand screen, Factor VIII, Factor IX (von Willebrand and factors not needed if bruise in the shape of an object), AST/ALT |

| Infant 6 to<12 mo of age not yet cruising with a bruise(s)a | Skeletal survey, CBC/platelets, PT/PTT, von Willebrand screen, Factor VIII, Factor IX (von Willebrand and factors not needed if bruise in the shape of an object), AST/ALT |

| Infant <12 mo of age with a non–motor vehicle–associated intracranial hemorrhageb | Skeletal survey, CBC/platelets, PT/PTT, Factor VIII, Factor IX, d-dimer, fibrinogen, AST/ALT |

| Children <2 y of age reported to Child Protective Services for concerns of physical abuse | Skeletal survey |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CBC: complete blood count; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PT: prothrombin time; PTT: partial thromboplastin time.

Other than a single bruise to a bony prominent after an age-appropriate trauma (eg, child 8 mo of age with a bruise to the forehead after a fall off a bed).

Not relevant for general emergency departments because infants with intracranial hemorrhage would all be transferred to a pediatric level I trauma center.

Compliance with AAP guidelines was assessed as fully compliant,” “partially compliant,” “not compliant” or “met clinical scenario but clinical judgment made evaluation unnecessary.” Fully, partially and not compliant were defined were defined as completing all parts, only some part or none of AAP recommended evaluation, respectively. “Met scenario but clinical judgment made evaluation unnecessary” was used in the following circumstances established a priori: injury occurred in a public place or was witnessed by a disinterested adult, a cruising or walking infant had a toddler’s fracture, the patient had a preexisting diagnosis (eg, hemophilia) that explained the injury or an infant 6 to <12 years old had a single bruise on a bony prominence after a developmentally appropriate trauma (eg, bruise to the forehead after a fall off a bed). Subjects in this group were not included in the denominator for the purposes of calculating compliance.

Children transferred to CHP from UPMC Hamot or UPMC Mercy were excluded because the objective of the study was not to evaluate compliance at CHP. If patients were transferred from UPMC Hamot to the burn unit at UPMC Mercy, the entire evaluation between both sites was used to assess compliance.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine demographic and compliance variables. The primary outcome was the proportion of cases in the preintervention and intervention groups in which the provider was compliant with the AAP guidelines for evaluation of suspected physical abuse. We also assessed whether compliance was related to patient and/or provider demographics. SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used for all analyses. A P value <.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Preintervention and intervention period

A total of 242 children <2 years of age triggered the alert system, 86 during the preintervention period and 156 during the intervention. The 242 children represented 4.3% of the 5564 children <2 years of age who presented to the UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy EDs during the preintervention and intervention period, but just 0.12% of all patients of any age who presented during this time. The proportion of all patients seen in the ED who were <2 years of age was significantly greater at UPMC Hamot than at UPMC Mercy (6.0% vs 0.9%; P < .001).

Seventy-four percent (180 of 242) of the subjects were evaluated at UPMC Hamot; 26% were evaluated at UPMC Mercy. Median age was 7.9 (interquartile range, 4.3-11.3) months of age and 9.3 (interquartile range, 5.1-14.6) months of age at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy, respectively; this difference was not significant (P = .09). Demographics of the patients who did not trigger the alert system were compared (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of demographics of children <2 years of age seen at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy during the preintervention and intervention period who did and did not trigger the CA-CDSS

| Children <2 y of age at UPMC Hamot who did not trigger the CA-CDSS (n = 4947) | Children <2 y of age at UPMC Hamot who triggered the CA-CDSS (n = 180) | χ2/P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 2768 (54) | 96 (53) | 0.01 (.924) |

| Caucasian | 3127 (61) | 120 (67) | 0.55 (.458) |

| Public insurance | 1076 (21) | 150 (83) | 162.39 (<.001) |

|

| |||

| Children <2 y of age at UPMC Mercy who did not trigger the CA-CDSS (n=617) | Children <2 y of age at UPMC Mercy who triggered the CA-CDSS (n = 62) | χ2/P | |

|

| |||

| Male | 366 (54) | 31 (50) | 0.11 (.743) |

| Caucasian | 224 (33) | 34 (55) | 5.10 (.024) |

| Public insurance | 196 (29) | 52 (84) | 28.93 (<.001) |

Values are n (%).

CA-CDSS: child abuse clinical decision support system, UPMC: University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

The frequency with which each trigger alerted the system is in Table 1. We did not identify a statistically significant difference in the most common triggers between the 2 sites. In 81% of cases (195 of 242), the trigger was considered appropriate insofar as the scenario that resulted in a trigger should have raised the concern for abuse; there was not a significant difference between the preintervention and intervention period. Seventy percent (33 of 47) of the overtriggers were due to the NLP.

In the preintervention period, 12% (10 of 86) of subjects who triggered the system met 1 of the 5 clinical scenarios compared with 28% (44 of 156) in the intervention period (P = .02) In 96% (149 of 156) of cases in the intervention period, the provider received the alert; 79% of the time the alert occurred when the chart was opened. The remainder of the time, the alert occurred when an order was placed. In the 4% (7 of 156) of cases in which the provider didn’t receive an alert, the provider did not open the EHR or place an order after the trigger occurred.

Compliance

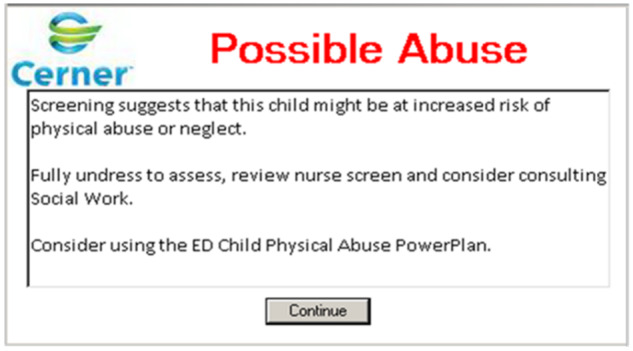

Preintervention and intervention period ( Figure 4 )

Figure 4.

Flow of subjects in both the preintervention period and intervention period including whether they met 1 of the 5 clinical scenarios for which compliance with American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guideline was being measured.

In 10 of the 65 cases in preintervention period in which it was reasonable to be concerned about abuse, the subject met 1 of the clinical scenarios; providers were fully compliant 70% (7 of 10) of the time and noncompliant 30% (3 of 10) of the time. In the intervention period, subject met a clinical scenario in 130 of the cases in which it was reasonable to be concerned about abuse; providers were fully compliant 34% (15 of 44) of the time, partially compliant 16% (7 of 44) of the time, and noncompliant 50% (22 of 44) of the time. There was no difference in the rate of noncompliance between the preintervention and intervention groups (P = .55).

The physical abuse order set was only used 6 times during the intervention period—5 times at UPMC Hamot and once at UPMC Mercy. Physicians were fully compliant in 83% (5 of 6) of the cases in which the physical abuse order set was used.

Case mix in the preintervention vs intervention period

The distribution of injuries identified in the preintervention vs intervention period is seen in Table 5. Every infant < 12 months of age in both the preintervention and intervention period with an intracranial hemorrhage was transferred to CHP.

Table 5.

A comparison of the injuries identified in the preintervention and intervention periods

| Clinical scenarios |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noncruising infant <12 mo of age with a fracture(s) | Infant <6 mo of age with a bruise(s) | Infant 6-11.9 mo of age not yet cruising with a bruise (s)a | Children <2 y of age reported to Child Protective Services for concerns of physical abuse (who did not meet other clinical scenarios) | Total number of unique children identified with injuries which were concerning for abuse | |

| Preintervention | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 10 |

| Intervention | 8 | 10 | 6 | 22 | 44b |

Other than a single bruise to a bony prominent after an age-appropriate trauma (eg, child 8 mo of age with a bruise to the forehead after a fall off a bed).

There are 2 children with both a fracture and a bruise.

Among the 54 subjects who met clinical scenarios plus the 9 who were transferred to CHP (and, therefore, excluded from the evaluation of compliance), there were 16 who were ultimately diagnosed with physical abuse.

Physician demographics and association with compliance

A total of 47 (n = 24 UPMC Hamot, n = 23 UPMC Mercy) attending physicians evaluated patients during the preintervention and intervention period: 83% were men, 91% were Caucasian, and all completed an emergency medicine residency. There was no association between any physician or patient demographic and compliance.

End-user feedback

In addition to the 51 attending physicians, an additional 88 APPs and medical residents evaluated patients with attending supervision. Of the 139 providers, 40 (29%) responded to the survey; 85% were physicians (either attendings or residents). Eighty percent (31 of 39) remembered receiving an alert. Fifty two percent (16 of 31) said that the alert altered their clinical decision making; 84% (32 of 38) never accessed the physical abuse order set.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to evaluate the use of an EHR-based CA-CDSS in general EDs and the use of NLP to identify at risk patients in real time. Improving identification and evaluation of physical abuse in general EDs is critical to decrease morbidity and mortality. While most children with severe injuries due to abuse are treated in pediatric trauma hospitals, ED care often occurs in general EDs30 where the rate of missed abuse is higher.12

The large increase in the number of subjects identified by the CA-CDSS and the corresponding increase in the number of children who met 1 of the clinical scenarios was unexpected. To assess whether this was due to an unexpectedly low level of triggering preintervention vs a high level in the intervention period, we reviewed data from the CA-CDSS in the same 2 hospitals in the 8 months after the intervention period (February 1, 2017, to September 30, 2017); 150 subjects triggered, almost identical to the number in the intervention period. There are likely several reasons for the increase number of patients who triggered during the intervention period. Perhaps most importantly, the child abuse screen was not present during the preintervention period; this accounted for 29 subjects in the intervention period. The other trigger that was significantly different between the 2 periods was the order for a skeletal survey, which triggered during the intervention period when it was not ordered from within the physical abuse order set. The increase in the ordering of skeletal surveys may the result of ongoing child abuse–related education. Increased awareness and recognition of concerning clinical features and improved nursing documentation likely resulted in additional NLP triggers. This would not be surprising, given the required nurse training before the intervention and the ongoing educational effort made by nurse stakeholders at both hospitals. There may be other factors that we have not identified.

The high baseline compliance rate of 70% and the lack of improvement after introduction of the CA-CDSS were unexpected but, in hindsight, are likely related to the change in the population of children being identified. In the preintervention period, only 10 children were identified with injuries which met a clinical scenario. More than 4 times as many children were identified during the intervention period. This is likely due to a combination of the overall increase in the number of subjects who triggered as discussed previously as well as the specificity of the triggers especially the child abuse screen. In the intervention period, the trigger system likely alerted physicians to the possibility of abuse in cases in which there were minor injuries—such as a single bruise in a 3-month-old child. This is the type of case in which the possibility of abuse was likely not even considered in the past. In contrast, there was no increase in the cases of abuse which required transport to a level I pediatric trauma center. A bruise is the most common type of sentinel injury, a medically minor but clinically important, initial symptom of abuse that is frequently not recognized or properly evaluated. In a study of 146 infants <6 months of age who were evaluated for abuse after presenting with what seemed to be an isolated bruise, 50% (73 of 146) had at least 1 additional injury identified when the AAP clinical guidelines were followed and skeletal survey, neuroimaging, or blood work was performed.31

We do not believe that the lack of a statistical difference between the compliance rates in the preintervention vs intervention groups was due to a type II error. Even if we assume a moderate effect size, a sample size as small as 10 should be able to detect a 20% difference in compliance at a power level of 0.8. We also do not believe that it is due to a secular trend: logistic regression with the dependent variable as compliance, the independent variable as pre- vs postintervention and the covariate as the date of the event demonstrates that all the logistic regression coefficients are nonsignificant. It is possible that the lack of evidence of a secular trend could be due to insufficient power.

Due to the study design, we do not know the sensitivity of the CA-CDSS and there may have been additional abuse cases among children who did not trigger. However, based on data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System,1 the rate of physical abuse in the study population is ∼0.33%. This suggests that among the ∼5500 children in the study, we expect to detect approximately 19 children with physical abuse. As described previously, we detected 16 children. If we applied the so-called rule of 3 for Bernoulli trials to estimate the sample size required to uncover 1 missed abuse case among those who did not trigger, it is likely that we would need to review 915 charts to potentially find even 1 false negative. Finding a very small number (say, 0 or 2) in the sample of patients who did not trigger would not necessarily help to calculate the sensitivity of our alert system.

The higher rate of public insurance among those who triggered compared with those who did not was not surprising, consistent with data demonstrating that poverty is a risk for child abuse32,33 and consistent with the data from our CA-CDSS in our pediatric hospital.28 The higher rate of triggering in black children at UPMC Mercy is likely related to a strong positive correlation between race and insurance at UPMC Mercy which is not present at UPMC Hamot.

The low number of cases in which the physical abuse order set was used was disappointing and unexpected given our experience at CHP where the order sets were rapidly incorporated into clinical use.27 There are several possible reasons for this lack of order set usage. The first may be that the provider did not agree with the recommendations in the order set or chose to ignore them; while 52% of providers stated that the alert changed their clinical decision making, a larger proportion probably should have had their clinical decision-making changed. There is minimal abuse-specific training or continuing education for general ED physicians; in a single 2011 study, general practitioners had significantly lower knowledge about child abuse compared with pediatric ED physicians in virtually every category evaluated.34 Anecdotally, the general ED physicians at both sites expressed on multiple occasions that they felt the AAP guidelines were unnecessary and that they could identify abuse based on their clinical judgment. Research does not support this, and is the reason why the AAP developed clinical guidelines.2,31,35 Data from pediatricians suggest that addressing both physician attitudes and cognitive factors are critical to improve compliance with AAP guidelines.36 It is possible that the infrequent use of the order set was related to the inability to link the alert directly to the order set; the Cerner platform in our general EDs does not have this functionality. Finally, the low use of the order set might be related to the relative rarity with which a given provider received the alert; even the provider who evaluated the greatest number of children with suspicious injuries evaluated a total of 14 patients over 16 months, which is fewer than 1 a month. The low volume of abuse cases for any given provider supports the use of CA-CDSS because clinical decision support can be particularly helpful for diseases and clinical situations that are rarely encountered by a provider.37,38 We are tracking whether continued availability of the CA-CDSS including the order set and ongoing child abuse–related education will increase order set use and compliance over time.

There are several limitations to this study. Perhaps most importantly, the study design—a before-and-after design—is not ideal. We considered multiple designs, but due to limitations of the EHR (eg, it is not possible to make changes to the EHR in only 1 hospital within the hospital system, which makes a randomization by hospital or an offsetting of the go-lives impossible), the lack of another hospital system with an identical EHR (which would have allowed randomization by hospitals in different hospital systems) and Institutional Research Board, ED leadership, and logistical issues related to a randomized controlled trial, we felt the before-and-after design was the best option. One of the significant concerns with this design is that it cannot account for secular trends that could influence the outcome (compliance) independent of the intervention (the CA-CDSS). However, given more than 20 years of data that demonstrate a lack of change in compliance with AAP guidelines despite improved awareness and ongoing provider education, we believe that it is highly unlikely there would be a secular change during the short time study period.

There is also a limitation related to the Cerner platform itself—it was not possible, for example, to link the alert to the order set. Scalability is another limitation given the different EHRs in different hospital systems; this is a limitation of the approach of using the EHR, however, rather than a limitation of the CA-CDSS per se.

CONCLUSION

A CA-CDSS, comprising a trigger-based alert system, a physician alert and an ED physical abuse order set, was embedded in the EHR in 2 general EDs. Identification of young children with injuries which met of the clinical scenarios increased 4-fold after the CA-CDSS was introduced. Compliance with AAP guidelines did not increase during the study period, although use of the physical abuse order set was strongly associated with compliance. Changes in compliance rates may be much slower in general EDs compared with a pediatric ED in which the absolute volume of children with suspicious injuries and the relative volume for any given provider is significantly higher, which allows for a faster learning curve.

FUNDING

Research reported in this publication was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award (AD-12-11-4956). The statements in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, its Board of Governors, or the Methodology Committee.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RPB was involved in the conception and design of the project, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, statistical analysis and obtaining funding, and approved the final manuscript as submitted and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work. BR was involved in the acquisition and interpretation of data, revision for important intellectual content, final approval of the version, and in agreement with the accuracy and integrity of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. JS was involved in the acquisition and interpretation of data, revision for important intellectual content, final approval of the version, and in agreement with the accuracy and integrity of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. JF was involved in the acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work. EH was involved in the acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work. TM was involved in the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and obtaining funding, approved the final manuscript as submitted and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work. RR was involved in the design of the study, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Donald Yealy, MD, for providing institutional support, without which this project would not have been successful; Richard Ambrosino, MD, Jessica Fesz, MS, and Martha Stambaugh, RN, for their informatics expertise and support. Ferdinando Mirarchi, MD, Karin Wickwire, CRNP, RN, and Debra Shane, RN, for providing ongoing teaching to the nurses at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy and for their overall support of the project. Ms Rosa Uccellini (UPMC Mercy) for obtaining data about the patient populations at UPMC Hamot and UPMC Mercy during the study periods. Lauren McCullagh, MPH (Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine), for her expertise related to clinical decision support. The PCORI Stakeholder Committee (Cathleen Palm, Center for Children’s Justice; Teresa Olsen, MEd, American Academy of Pediatrics; Michele Poole; Sean Frederick, MD (UPMC), Patrick Donohue, JD, MBA (Founder, the Sarah Jane Brain Foundation), Kathleen Schenkel MSN, RN (UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh), and Rick Kidwell, JD (Senior Associate Counsel, VP Risk Management, UPMC), for their quarterly review, feedback, and suggestions related to conduct of the study. Mr Donohue, Ms Palm, and Ms Poole received compensation from grant support. Written permission to be acknowledged has been received.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2016. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families; 2017.

- 2. Jenny C, Hymel KP, Ritzen A, Reinert SE, Hay TC.. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA 1999; 2817: 621–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ravichandiran N, Schuh S, Bejuk M.. Delayed identification of pediatric abuse-related fractures. Pediatrics 2010; 1251: 60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. King WK, Kiesel EL, Simon HK.. Child abuse fatalities: are we missing opportunities for intervention? Pediatric Emergency Care 2006; 224: 211–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pierce MC, Smith S, Kaczor K.. Bruising in infants: those with a bruise may be abused. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009; 2512: 845–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thackeray JD. Frena tears and abusive head injury: a cautionary tale. Pediatr Emerg Care 2007; 2310: 735–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oral R, Yagmur F, Nashelsky M, Turkmen M, Kirby P.. Fatal abusive head trauma cases: consequence of medical staff missing milder forms of physical abuse. Pediatr Emerg Care 2008; 2412: 816–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guenther E, Powers A, Srivastava R, Bonkowsky JL.. Abusive head trauma in children presenting with an apparent life-threatening event. J Pediatr 2010; 1575: 821–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flaherty EG, Perez-Rossello JM, Levine MA, et al. Evaluating children with fractures for child physical abuse. Pediatrics 2014; 1332: e477–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anderst JD, Carpenter SL, Abshire TC.. Evaluation for bleeding disorders in suspected child abuse. Pediatrics 2013; 1314: e1314–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Christian CW, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics 2015; 1355: e1337–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Trokel M, Wadimmba A, Griffith J, Sege R.. Variation in the diagnosis of child abuse in severely injured infants. Pediatrics 2006; 1173: 722–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wood JN, Feudtner C, Medina SP, Luan X, Localio R, Rubin DM.. Variation in occult injury screening for children with suspected abuse in selected US Children's hospitals. Pediatrics 2012; 1305: 853–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lane WG, Dubowitz H.. What factors affect the identification and reporting of child abuse-related fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007; 461: 219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rangel EL, Cook BS, Bennett BL, Shebesta K, Ying J, Falcone RA.. Eliminating disparity in evaluation for abuse in infants with head injury: use of a screening guideline. J Pediatr Surg 2009; 446: 1229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lane WG, Rubin DM, Monteith R, Christian CW.. Racial differences in the evaluation of pediatric fractures for physical abuse. JAMA 2002; 28813: 1603–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wood JN, Hall M, Schilling S, Keren R, Mitra N, Rubin DM.. Disparities in the evaluation and diagnosis of abuse among infants with traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics 2010; 1263: 408–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wood JN, Christian CW, Adams CM, Rubin DM.. Skeletal surveys in infants with isolated skull fractures. Pediatrics 2009; 1232: e247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wood JN, French B, Song L, Feudtner C.. Evaluation for occult fractures in injured children. Pediatrics 2015; 1362: 232–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Madlon-Kay D. Clinician adherence to guideline for phototherapy use in newborn. J Am Board Fam Med 2012; 254: 437–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vernacchio L, Vezina R, Mitchell A.. Management of acute otitis media by primary care physicians: trends since the release of the 2004 American Academy of Pediatrics/American Academy of Family Physicians clinical practice guideline. Pediatrics 2007; 1202: 281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guerra CE, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Brown JS, Halbert CH, Shea JA.. Barriers of and facilitators to physician recommendation of colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 2212: 1681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shiffman RN, Liaw Y, Brandt CA, Corb GJ.. Computer-based guideline implementation systems: a systematic review of functionality and effectiveness. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1999; 62: 104–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cebul RD, Love TE, Jain AK, Hebert CJ.. Electronic health records and quality of diabetes care. N Engl J Med 2011; 3659: 825–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gill JM, Mainous AG 3rd, Koopman RJ, et al. Impact of EHR-based clinical decision support on adherence to guidelines for patients on NSAIDs: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2011; 91: 22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smythe MA, Mehta TP, Koerber JM, et al. Development and implementation of a comprehensive heparin-induced thrombocytopenia recognition and management protocol. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2012; 693: 241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suresh S, Saladino RA, Fromkin J, et al. Integration of physical abuse clinical decision support into the electronic health record at a Tertiary Care Children's Hospital. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 257: 833–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berger RP, Saladino RA, Fromkin J, Heineman E, Suresh S, McGinn T.. Development of an electronic medical record-based child physical abuse alert system. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 252: 142–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rumball-Smith J, Fromkin J, Rosenthal B, et al. Implementation of routine electronic health record-based child abuse screening in General Emergency Departments. Child Abuse Negl 2018; 85: 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW.. Emergency care for children in pediatric and general emergency departments. Pediatr Emerg Care 2007; 232: 94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr 2014; 1652: 383–8 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eckenrode J, Smith EG, McCarthy ME, Dineen M.. Income inequality and child maltreatment in the United States. Pediatrics 2014; 1333: 454–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lanier P, Maguire-Jack K, Walsh T, Drake B, Hubel G.. Race and ethnic differences in early childhood maltreatment in the United States. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2014; 357: 419–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Menoch M, Zimmerman S, Garcia-Filion P, Bulloch B.. Child abuse education: an objective evaluation of resident and attending physician knowledge. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011; 2710: 937–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Feldman KW, Tayama TM, Strickler LE, et al. A prospective study of the causes of bruises in premobile infants. Pediatr Emerg Care 2017. Oct 16 [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Flaherty EG, Sege R, Price LL, Christoffel KK, Norton DP, O’Connor KG.. Pediatrician characteristics associated with child abuse identification and reporting: results from a national survey of pediatricians. Child Maltreat 2006; 114: 361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mainous AG, Carek PJ, Lynch K, et al. Effectiveness of clinical decision support based intervention in the improvement of care for adult sickle cell disease patients in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 2018; 315: 812–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G.. Understanding and reducing ceruloplasmin overuse with a decision support intervention for liver disease evaluation. Am J Med 2016; 1291: 115.e17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]