Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize information on the use of teledentistry in the diagnosis of oral lesions.

Materials and Methods

A systematic literature search conducted in August 2018 included articles published until December 2018 in 4 databases. Two reviewers evaluated the search results separately. If they were uncertain as to whether to include an article, a third reviewer made the final decision. Studies related to the diagnosis of oral lesions using teledentistry were included. The methodological quality of the studies was analyzed using the Quality Assessment of Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy.

Results

Eleven articles were included in the study. The selected articles were published between 1999 and 2018, predominantly in developing countries. The professionals acting as patient examiners are dental students and dentists, as well as other health professionals. Most of the patients evaluated in the studies were from rural populations or locations distant from large centers. The tools used to obtain patient data were smartphones, videoconference, email, questionnaires, histopathological exams, and telemedicine applications and systems. Most studies concluded that there is a high level of agreement between teledentistry and clinical consultation and that the use of this resource for diagnostic purposes can reduce costs and the travel time to consult a specialist personally. Nine of the 11 studies were of good quality.

Conclusions

Teledentistry has the potential to improve the care quality related to diagnosis and management of oral lesions, shortening distances between patients who need specialized diagnoses and specialists.

Keywords: teledentistry, oral diseases, diagnosis, oral medicine, oral medicine

INTRODUCTION

Teledentistry can be generically described as the use of information technology in dental practice, education, research, and management. It has provided access to dental care in rural and geographically disadvantaged areas. Moreover, it provides clinical support to dentists of different specialties and aims to improve the health care provided to the population.1,2 The type of interaction provided by teledentistry classifies it as synchronous or asynchronous. In asynchronous teledentistry, the information can be recorded for later analysis, as in an email. In synchronous teledentistry, the interaction is in real time (eg, a videoconference).3

The major benefit of teledentistry is to reduce health inequalities, promote better access to expert opinion, optimize time and quality, and reduce waiting lists.1,3 Patients should have faster access to diagnosis and management of their health conditions with the incorporation of teledentistry in oral health services, with more convenience and less traveling to health centers. Moreover, teledentistry provides access to various types of health care (primary, secondary, and tertiary), improves quality of life, promotes professional education, improves tele-education programs, and reduces health costs.1–3

Teleconsultation allows professionals from different specialties to discuss diagnosis, treatment plan, and preservation, contributing to a greater resolution of clinical cases.4 The difficult diagnosis of oral lesions is one of the causes for delayed diagnosis of oral cancer.5 In this sense, by providing communication between clinical dentists and specialists, teledentistry helps in the early diagnosis of malignant lesions, providing faster measures for the treatment of oral cancer and increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of the treatment.2

Teledentistry has evolved in recent years, with especial emphasis on interactive tele-education, tele-assistance, and multicentric research production.4 However, the subject has not been sufficiently studied so far, particularly regarding oral lesions.2,3,6–9 The objective of this systematic review is to survey existing information on the use of telediagnosis in oral medicine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study follows the criteria recommended by PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses)10 and was included in the PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews) database (CRD42018107002).

Literature research

The following databases were accessed: PubMed, Embase, LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences, and SUMSearch. The CAPES (bancodetes.capes.gov.br/) and Google Scholar databases were used to identify additional gray literature. The keywords were defined by specific descriptors: Medline (MeSH [Medical Subject Headings]), Embase (Emtree), LILACS (DeCS [Descriptors in Health Sciences]), SUMSearch (MeSH), and CAPES (DeCS), with combinations of the following terms: “oral medicine,” “disease, mouth,” “diseases, mouth,” “mouth disease,” “oral diseases,” telemedicine, “mobile health,” “health, mobile,” mhealth, telehealth, ehealth, teledentistry, diagnosis, “diagnoses and examinations,” “examinations and diagnoses,” education, workshops, “training programs,” “program, training,” “programs, training,” “training program,” “educational activities,” “activities, educational,” “activity, educational,” “educational activity,” “literacy programs,” and “literacy program.” In addition, manual searches of the reference lists of all selected studies were performed to identify other eligible studies.

Eligibility criteria

No limits were placed on type or language of the study. Original articles published until December 2018 on the diagnosis of oral lesions by teledentistry were considered eligible for inclusion. Nonoriginal articles (reviews, editorials, letters, comments, and book chapters) were excluded.

Data review and extraction

The initial selection was based on the evaluation of titles and abstracts, followed by full text analysis by 2 authors (APdCF, SAL). Discrepancies related to inclusion and exclusion were analyzed by a third examiner (VCC). Articles meeting the inclusion criteria were retained.

The first author (APdCF) extracted the data (first author, year, database, type of teledentistry, country, professionals involved, journals, methods, and main results) from the full texts, and the other reviewer (SAL) independently verified the extracted data.

Bias risk and quality evaluations

The bias risk and quality analyses of the study were performed independently by 2 authors (APdCF, SAL) using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies questionnaire (Table 1).11 This questionnaire is a tool widely to assess the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies individually used in a systematic review in terms of potential risks of bias and applicability. It is structured in a list of 14 questions that are answered by “yes,” “no,” or “uncertain.” In order to answer such questions, in addition to the analysis of the studies, the description of each item was evaluated in detail according to Whiting et al.12

Table 1.

Evaluation of the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies questionnaire)11

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Patient representation |

| 2 | Clear selection criteria |

| 3 | Reference standard for classifying the target condition |

| 4 | Enough time between the reference standard and the test |

| 5 | The sample is checked using a reference standard |

| 6 | Patient receives the same reference standard |

| 7 | Independent reference standard |

| 8 | Test described in detail |

| 9 | Reference standard described in detail |

| 10 | Results interpreted without knowledge of index test |

| 11 | Reference standard results interpreted without the knowledge of the index test |

| 12 | Available clinical data |

| 13 | Intermediate/uninterpretable results reported |

| 14 | Explained exclusions |

RESULTS

The search with the terms used in the 3 databases and in the gray literature resulted in 173 articles, excluding all duplicated articles in the searched databases. Among them, 81 were excluded and 57 were included in the analysis by the examiners (agreement rate of 79.8%). Discrepancies in relation to inclusion and exclusion of the article in the study were assessed by a third examiner (VCC), who decided to include 17 of 35 remaining articles.

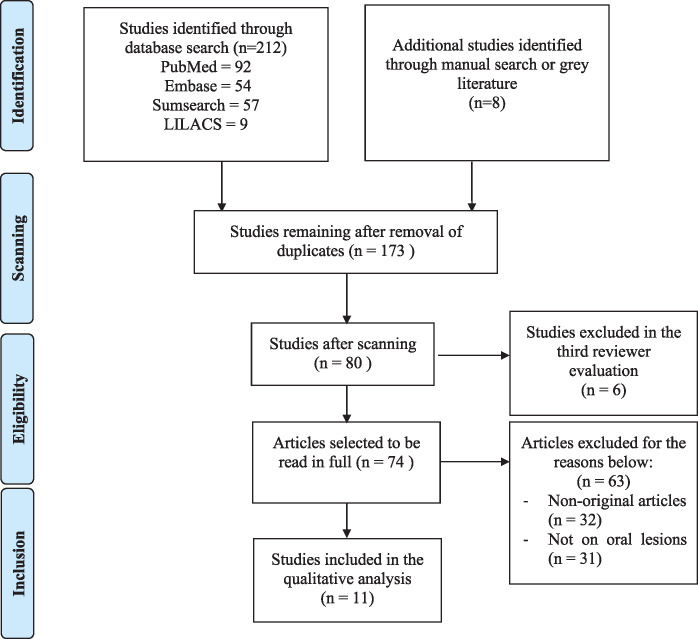

After reading the titles and abstracts, 74 articles were selected for full reading. After the review of 74 studies, only 11 articles met the selection criteria and were included in the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart summarizing the systematic review process.

The publication dates of the 11 selected articles ranged from 1999 to 2018. Most studies were conducted in Brazil (n = 6) and the United Kingdom (n = 2). The professionals involved in the research as patient examiners vary from doctors, nurses, and nutritionists to dental students, general practitioners, and specialists. Most of the journals in which the articles were published are in the field of telemedicine (n = 5). The journals that were not in the field of telemedicine were national (Brazilian, British, and American), with the exception of an Italian article that was published in an international magazine. In most studies, the sample came from rural areas or remote locations. The study from India used patients with risk behavior for oral cancer compared with a population of selected cases from the clinic of the reference center studied. The type of action was asynchronous in most studies (n = 10). Only 1 study combined synchronous and asynchronous action.5 Synchronous case discussion has not been reported so far. The tools used to obtain patient data were clinical photographs and image exam photographs taken with a smartphone, videoconference, email, questionnaires, histopathological exams, and telemedicine applications and platforms. In general, the studies were cross-sectional, with only 1 paired clinical trial.13 Most studies concluded that there is good agreement between teledentistry and clinical consultation, demonstrating good accuracy. Some studies concluded that teledentistry provides more access to dental care for the rural population, reducing travel time for specialized consultations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data extracted from the studies evaluated

| Author (year), country | Objective of the study | Professional | Target population | Results and comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leão et al (1999),13 United Kingdom | To determine the acceptability of recording and transmitting clinical images of patients with oral lesions via Internet | Qualified clinical and nonclinical dentists | Dental school patients (n = 60) |

|

| Eastman Dental Institute | ||||

| Torres-Pereira et al (2008),14 Brazil | To evaluate the feasibility of remote diagnosis of oral diseases using the transmission of digital images by email | Dentists and oral medicine specialists | Rural population of a primary health care service |

|

| Bradley et al (2010),15 New Zealand | To evaluate the feasibility of using teledentistry to reference cases of oral lesions using a teledentistry prototype | Dentists and specialists (dentists) | Dental clinic community patients (n = 41) |

|

| Blomstrand et al (2012),16 Sweden | To streamline the consultation process, improve the skills of the professionals involved, and promote cost reduction actions | Oral hygiene technicians, dentists, and consultants | Dental school patients (n = 10) |

|

| Torres-Pereira et al (2013),17 Brazil | To evaluate the applicability of telediagnosis in oral medicine through the transmission of clinical images by email | Applicators: dentists | Dental school patients (n = 60) |

|

| Consultants: specialists in oral medicine | ||||

| Birur et al (2015),18 India | To develop a mobile phone–based platform for risk stratification and evaluation of oral lesions | Dentists and specialists (dentists) | Rural patients and people exposed to risk factors for oral cancer (n = 191) | Telediagnosis for oral lesions optimizes professional resources in the early detection of asymptomatic and neoplastic lesions. |

| Petruzzi et al (2016),19 Italy | To describe the use of the WhatsApp mobile application to share oral medicine clinical information | Dentists, doctors, oral hygiene technicians, and patients | Rural population (n = 96) |

|

| Fonseca et al (2016),20 Brazil | To evaluate diagnostic accuracy between the presential evaluation of oral lesions and the proposed remote diagnostic hypothesis | Oral medicine specialists (n = 2) | Dental school patients (n = 23 patients, 43 lesions) | There was optimal concordance (91% and 87%). |

| Haron et al (2017),21 Malaysia | To examine agreement in the clinical diagnosis of oral lesions with high risk of malignancy (conventional × teledentistry) | Oral medicine specialists and dentists | Dental school patients |

|

| Roxo-Gonçalves et al (2017),5 Brazil | To evaluate the diagnostic skills of primary care health professionals in relation to oral cancer and offer them distance learning courses | Dentists, oral medicine specialists, nutritionists, and nurses | Clinical images obtained from IARC/WHO |

|

| Carrard et al (2018),22 Brazil | To summarize the experience of a telemedicine program for primary care doctors and dentists | Dentists, doctors, and oral medicine specialists | Primary care patients (n = 259) |

|

IARC: Interagency for Research on Cancer; WHO: World Health Organization.

The evaluation of study quality should consider including both internal and external validity of a study; accuracy results should not be biased, and the results obtained should be relevant in clinical practice. This evaluation was performed by both authors (APdCF, SAL) and the results are presented in Table 3. The results of the questionnaires ranged from 5 to 12. Nine of the 11 studies presented good quality (more than 60% of the questions answered were yes).2 All studies analyzed presented samples with clear selection criteria (items 1 and 2 of the questionnaire). Study heterogeneity made it impossible to perform a meta-analysis.

Table 3.

Results of quality evaluation by 2 reviewers

| Item | Leão et al (1999)13 | Torres-Pereira et al (2008)14 | Bradley et al (2010)15 | Blomstrand et al (2012)16 | Torres-Pereira et al (2013)17 | Birur et al (2015)18 | Petruzzi et al (2016)19 | Fonseca et al (2016)20 | Haron et al (2017)21 | Roxo-Gonçalves et al (2017)5 | Carrard et al (2018)22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| 4 | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | Y | N | Y | U | N |

| 5 | U | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| 6 | U | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 7 | Y | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 8 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 9 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 10 | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| 11 | N | U | U | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | N | Y |

| 12 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 13 | N | N | U | N | U | N | U | N | N | N | N |

| 14 | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | U | Y | N |

| Total | 5 of 14 | 10 of 14 | 12 of 14 | 11 of 14 | 10 of 14 | 8 of 14 | 12 of 14 | 7 of 14 | 12 of 14 | 10 of 14 | 9 of 14 |

N: no; U: undefined; Y: yes.

DISCUSSION

The beginning of the history of teledentistry dates back to 1994, with the first study on the subject completed in the American Armed Forces.23 Since then, other studies have been conducted in the area of teledentistry, but few focused on oral lesion diagnosis.

In their systematic review of teledentistry, Mariño et al9 observed that most studies on teledentistry were conducted in the United States, and there were no studies in developing countries. The data from the present study corroborates these findings as it reports that in relation to the diagnosis of oral lesions, most studies were conducted in developing countries (6 studies in Brazil, 1 study in Malaysia, and 1 in India), with few studies coming from developed countries (1 in the United States, 1 in Sweden, 1 in Italy, and 2 in the United Kingdom).

The results presented here show that the professionals involved as case examiners were students and dental professionals, specialists, and nonspecialists. Other health professionals were also used as examiners, such as doctors, nurses, and nutritionists. The use of various health professionals, in addition to dental students and dentists, is in line with the literature, which reports that nurses, often employed as primary health care professionals, are widely used as examiners of patients with oral lesions.23 This initiative of training several primary health care professionals has been recommended by the World Health Organization as a strategy to fight oral cancer by detecting early lesions.24,25

As for type, asynchronous teledentistry was the most used type in the articles included in this review. This methodology, in which data are obtained, stored in electronic devices, and used later, is also the most frequent one found in other studies that address the subject of teledentistry in a comprehensive manner. Apparently, this strategy is more convenient to the professionals who act as consultants in these processes, as they do not need to be available all the time.23

Nayar et al1 reported that the materials used in teledentistry training included classes given by teleconsultants, PowerPoint presentations, video clips, manuals, and teledentistry platforms. In the articles selected in this study, patient data were obtained using clinical photographs and imaging exam photographs obtained with a smartphone, video conference, email, questionnaires, histopathological exams, and telemedicine applications and systems. The improvement of image acquisition through smartphones and through the advancement of other image, software, and Internet technologies has favored the expansion of teledentistry programs.7,26

The results of some studies show that remote diagnosis can be an interesting tool for the detection of oral lesions.7,23,26 Moreover, the involvement of more than 1 consultant in the diagnostic process seems to be an interesting strategy to increase the accuracy of remote diagnosis.23,27,28 These findings support the results of this systematic review.

Some studies evaluated the level of patient satisfaction with the use of teledentistry in general. Nayar et al1 obtained a good level of patient satisfaction regarding teledentistry. The reasons mentioned included fewer visits to hospitals, less traveling time, and short waiting period for orthodontic care. This study also reported that the level of satisfaction of clinical dentists regarding teledentistry was due to better communication with specialists and better treatment guidance for clinicians. This type of evaluation was not found in any of the studies included in this review.

Blomstrand et al16 stated that teledentistry could reduce health costs. Other authors provided a history of the use of teledentistry applications and considered its potential to improve quality access and reduce dental care costs for a larger percentage of the population.3,29,30 These last statements corroborate a study by Carrard et al22 that shows the potential of a telediagnosis service in oral medicine to reduce the referral of cases considered simpler and that could be treated in the primary care system.

On the other hand, some difficulties in incorporating the use of teledentistry as a common tool need to be recognized, including lack of training, discomfort with technology, equipment costs,1 and ethical issues, such as confidentiality of patient data.31

LIMITATIONS OF THIS SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Evaluation of quality of studies

Although most of the studies were of good quality when evaluated individually in this study (60%), the heterogeneity of the methodologies used does not allow their use in a meta-analysis. As a result, the systematic reviews published on teledentistry are generally descriptive.

Owing to the heterogeneity of the methodologies used in the studies included in this review, it is also difficult to generalize the results. It should be recognized that there is a paucity of studies on the topic in question, even after performing a rigorous search. Taking the lack of robust evidence into account, further studies are necessary, particularly in different countries, in order to confirm the present noteworthy findings.

CONCLUSION

Teledentistry can assist patients who need specialized diagnosis in dentistry and consultations with specialists in this area. So far, the studies show satisfactory agreement between presential and remote diagnosis using teledentistry, showing good acceptance by patients and professionals. However, studies with a more rigorous experimental design should be conducted in order to obtain results that can be generalized.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

APdCF was involved in conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the manuscript and approving its final version. SAL was involved in design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data, and approving the final version of the manuscript. CGM-B and VLdOG were involved in conception of the work, interpretation of data, and approving the final version of the manuscript. RNU and MRG were involved in conception of the work and approving the final version of the manuscript. VCC was involved in conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the manuscript and approving its final version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nayar P, McFarland K, Chandak A, Gupta N.. Readiness for teledentistry: validation of a tool for oral health professionals. J Med Syst 2017; 41 (1): 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alabdullah JH, Daniel SJ.. A systematic review on the validity of teledentistry. Telemed J E Health 2018; 24 (8): 639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daniel SJ, Kumar S.. Teledentistry: a key component in access to care. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2014; 14: 201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haddad AE. Dentistry in the Unified Health System (SUS), the national policy of education of health professionals in Brazil, the use of teledentistry as a tool for teaching-and-learning process and the creation of the Teledentistry Center at the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of São Paulo [TESE]. São Paulo, Brazil: Teledentistry Center at the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of São Paulo; 2011.

- 5. Roxo-Gonçalves M, Strey JR, Bavaresco CS, et al. Teledentistry: A tool to promote continuing education actions on oral medicine for primary healthcare professionals. Telemed J E Health 2017; 23 (4): 327–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Estai M, Kanagasingam Y, Xiao D, et al. A proof-of-concept evaluation of a cloud-based store-and-forward telemedicine app for screening for oral diseases. J Telemed Telecare 2016; 22 (6): 319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Irving M, Stewart R, Spallek H, et al. Using teledentistry in clinical practice as an enabler to improve access to clinical care: a qualitative systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2018; 24 (3): 129–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan S, Omar H, Medicine O.. Teledentistry in practice: literature review. Telemed J E Health 2013; 19 (7): 565–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mariño R, Ghanim A.. Teledentistry: a systematic review of the literature. J Telemed Telecare 2013; 19 (4): 179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG.. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peixoto R, Lucas SR. [ UFMG teledentistry program]. Rev Abeno 2013; 11 (1): 71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, et al. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003; 3 (1): 3–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leão JC, Porter SR. Telediagnosis of Oral Diseases. Braz Dent J 1999; 10 (1): 47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Torres-Pereira C, Possebon RS, Simões A, et al. Email for distance diagnosis of oral diseases: a preliminary study of teledentistry. J Telemed Telecare 2008; 14 (8): 435–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bradley M, Black P, Noble S, Thompson R, Lamey PJ.. Application of teledentistry in oral medicinein a community dental service. Br Dent J 2010; 209 (8): 399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blomstrand L, Sand LP, Gullbrandsson L, et al. Telemedicine: a complement to traditional refarrals in oral medicine. Telemed J E Health 2012; 18 (7): 549–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Torres-Pereira CC, Morosini I, Possebon RS, et al. Teledentistry: distant diagnosis of oral disease using e-mails. Telemed J E Health 2013; 19 (2): 117–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Birur PN, Sunny SP, Jena S, Kandasarma U, Raghavan S, et al. Mobile health application for remote oral cancer surveillance. J Am Dent Assoc 2015; 146 (12): 886–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Petruzzi M, De Benedittis M.. WhatsApp: A telemedicine platform for facilitating remote Oral Medicineconsultation and improving clinical examinations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016; 121 (3): 248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fonseca BB, Amenábar JM, Piazzetta CM, et al. Remote diagnosis of oral lesions with smartphone photos. Rev Assoc Paul Cir Dent 2016; 70 (1): 52–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haron N, Zain RB, Nabillah WM, et al. Mobile phone imaging in low resource settings for early detection of oral cancer and concordance with clinical oral examination. Telemed J E Health 2017; 23 (3): 192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrard VC, Roxo-Gonçalves M, Rodrigues JS, et al. Telediagnosis of oral lesions in primary care: the EstomatoNet Program. Oral Dis 2018; 24 (6): 1012–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rocca M, Kudryk V, Pajak J, et al. The evolution of a teledentistry system within the Department of Defense. Proc AMIA Symp 1999; 1999: 921–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Queyroux A, Saricassapian B, Herzog D, et al. Accuracy of teledentistry for diagosing dental pathology using direct examination as a gold standard: results of the tel-e-dent study of older adults living in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017; 18 (6): 528–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Petersen PE. Oral cancer prevention and control: the approach of the World Health Organization. Oral Oncol 2009; 45 (4–5): 454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McFarland KK, Nayar P, Chandak A, et al. Formative evaluation of a teledentistry training programme for oral health professionals. Eur J Dent Educ 2018; 22 (2): 109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fricton J, Chen H.. Using teledentistry to improve access to dental care for the underserved. Dent Clin N Am 2009; 53 (3): 537–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meurer M, Wangenheim A, Zimmermann C, et al. Plataforma colaborativa multimídia para apoio ao diagnóstico de lesões bucais em ambientes de teleodontologia. Rev Abeno 2014; 13 (2): 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Martinez-Beneyto Y, et al. Influence of years of professional experience in relation to the diagnostic skill of general dental practioners (GPDs) in identifying oral cancer and precancerous lesions. Int Dent J 2008; 58 (3): 127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sanchez ED, Lefebvre C, Abeyta K.. Teledentistry in the United States: a new horizon of dental care. Int J Dent Hyg 2004; 2 (4): 161–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gambino O, Lima F, Pirrone R, et al. A teledentistry system for the second opinion. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2014; 2014: 1378–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]