Abstract

Quantum Mechanical (QM) cluster models are used to probe effects due to the metal ions and active site residues on the catalytic properties of Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). The calculations suggest that the phosphoryl transfer transition states in PP1 is synchronous in nature with a significant degree of P-Olg cleavage, while those in AP are tighter, with a modest degree of P-Olg cleavage and a range of P-Onuc formation. Similar to observations made in our recent work, a significant degree of cross talk between the forming and breaking P-O bonds complicates the interpretation of Brønsted relation, especially for AP, for which computed βlg/βEQ,lg does not correlate with the degree of P-Olg cleavage, regardless of the metal ions in the active site. By comparison, the correlation between βlg/βEQ,lg and P-Olg bond order is more applicable to PP1, which generally exhibits less variation in the transition state than AP. Results for computational models with swapped metal ions between PP1 and AP suggest that the metal ions modulate both the nature of the transition state and the degrees of sensitivity of transition state to the leaving group. In the reactant state, the degree of the scissile bond polarization is also different in the two enzymes, although this difference appears to be largely determined by the active site residues rather than the metal ions. Therefore, both identity of the metal ion and positioning of polar/charged residues in the active site contribute to the distinct catalytic characteristics of these enzymes. Several discrepancies observed between the QM cluster results and available experimental data highlight the need of further QM/MM method developments for quantitative analysis of metalloenzymes that contain open-shell transition metal ions.

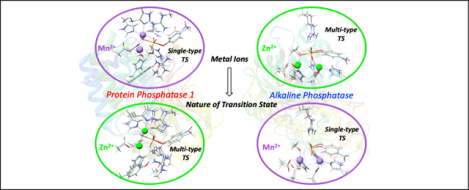

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Understanding the origin of enzyme catalysis requires determination of the geometry, electronic structure and free energy of transition state.1–4 For metalloenzymes, which constitute approximately 40% of known enzymes,5 a fundamental question concerns the relative importance of the catalytic metal ion(s) and nearby protein residues in determining the properties of transition state. Answering such a question is essential to the understanding of in vivo metal selectivity of enzymes6,7 as well as to the rational design of metalloenzymes with novel catalytic activities.8–10

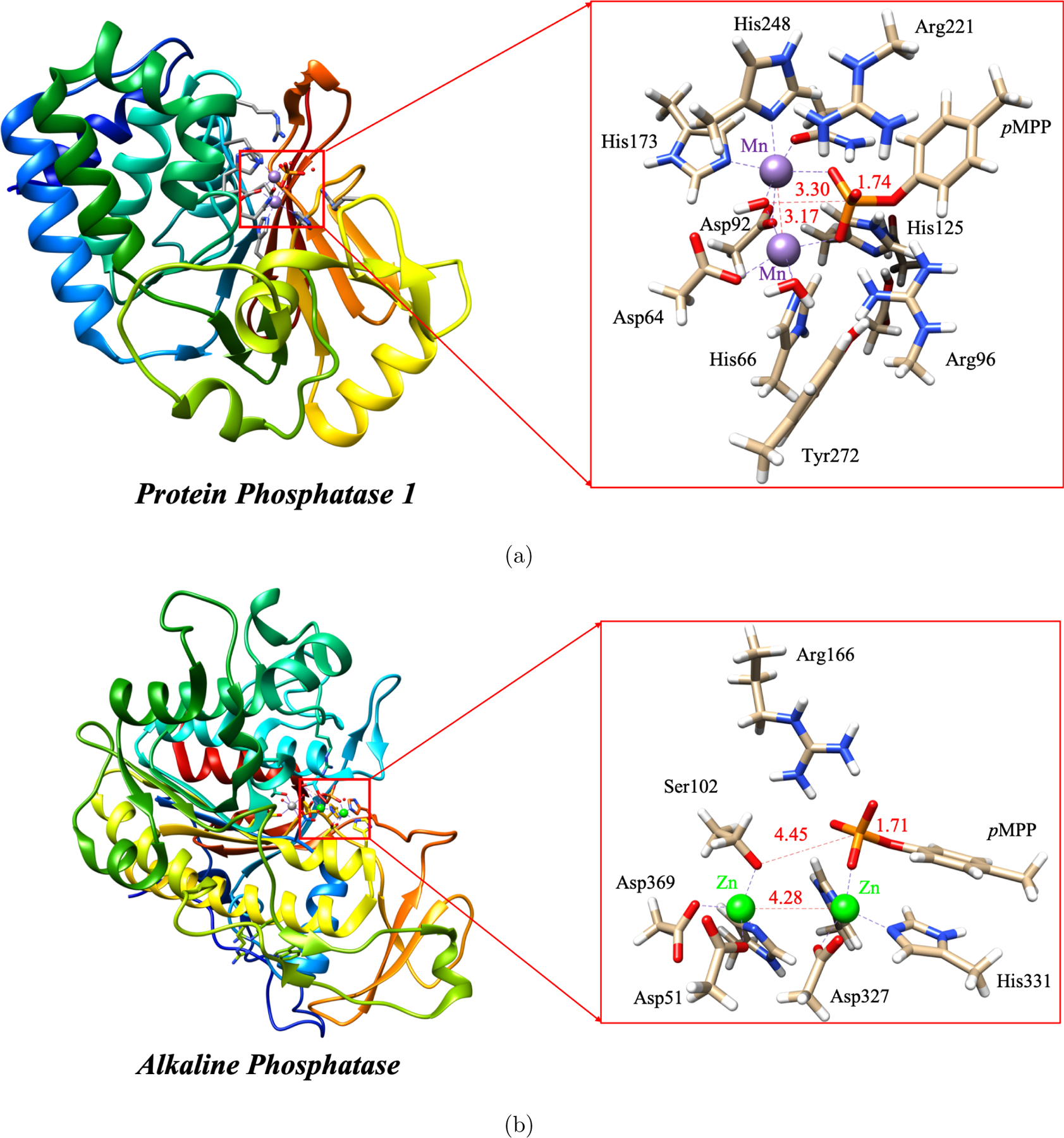

In this context, alkaline phosphate (AP) and protein phosphatase-1 (PP1) form a particularly interesting pair of systems. As shown in Fig. 1, both AP and PP1 feature a bimetallic binding site for phosphate substrates, and both active sites are rather open and solvent accessible, giving rise to a high level of catalytic promiscuity11–15 towards a broad set of phosphate substrates (Scheme 1 and Scheme 2).16–19 The latter feature made it possible to conduct free energy relation analysis20,21 for both AP and PP1, leading to valuable insights into the nature of transition state in these enzymes. In AP, the Brønsted constants for the leaving group (βlg) of phosphate monoesters and diesters were found to be similar to those for the corresponding uncatalyzed reactions in solution, an observation interpreted to suggest that the transition states in AP resemble those in solution and are distinct for monoesters and diesters.22–24 In PP1, by contrast, the βlg values for aryl methylphosphonates and aryl phosphate monoesters were measured to be essentially identical, although the corresponding solution values were very different.25 Similar to trends in the βlg values, experimental kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) for PP1 with different types of substrates are comparable to one another, while being different from those in solution.25 In AP, by contrast, the KIEs for monoesters and diesters are significantly different.26,27 Therefore, it appears that while AP accommodates different types of transition state structures for cognate and non-cognate substrates, PP1 stabilizes a single type of transition state for different classes of substrates; the latter was generally supported by our recent computational study,28 although calculations also noted differences between the phosphate and phosphonate transition states, which are manifested in not only structure but also kinetic isotope effects.

Figure 1:

The Protein Phosphatase-1 (PP1) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) feature a similar bimetallic binding site for a broad class of phosphate substrates (see Scheme 1). Shown in the boxes are the QM cluster models for the active site used here to compare the reactivities of PP1 and AP.

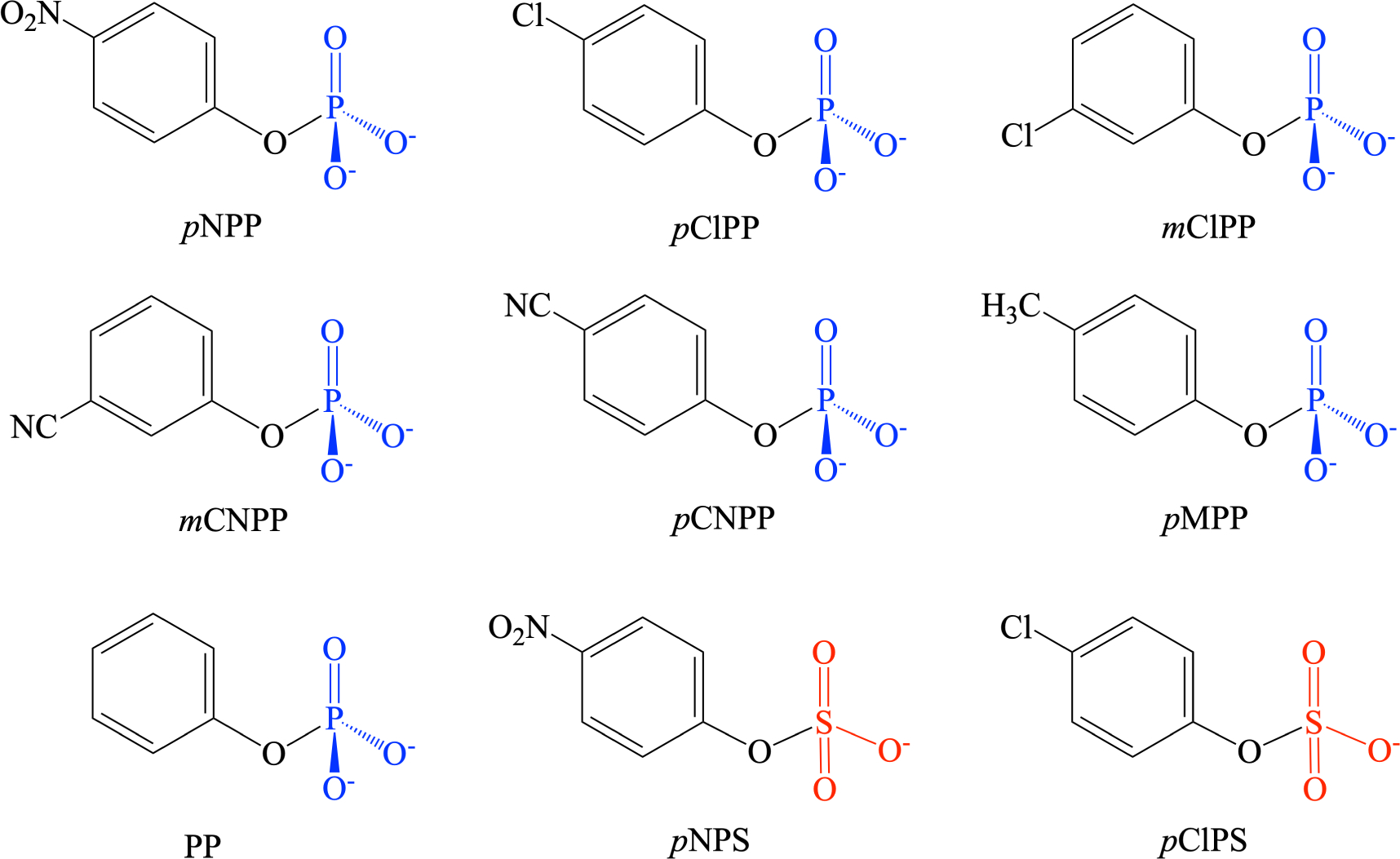

Scheme 1:

Aryl Phosphate substrates for PP1 and AP studied in this work

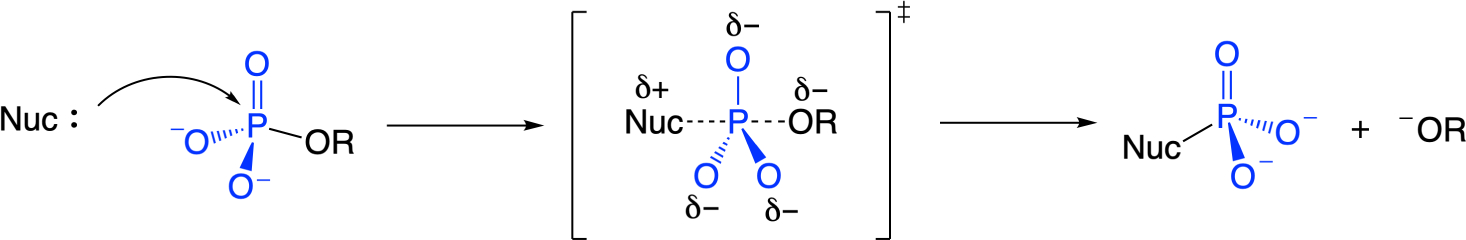

Scheme 2:

Phosphate monoester hydrolysis through a concerted pathway: bond formation to the nucleophile and bond fission to the leaving group occur simultaneously but not necessarily synchronously.

Another intriguing difference between AP and PP1 lies in their activities toward sulfate. AP was shown16,18,29 to catalyze the hydrolysis of sulfate monoesters with a proficiency 102 to 109 fold lower than that of phosphate monoesters; nevertheless, the reactivity is still 106 to 1013 fold higher than the uncatalyzed reaction in solution. By contrast, the recent work of Chu et al. demonstrated25 that p-nitrophenyl sulfate (pNPS) was not a substrate for PP1, even at high substrate concentrations and long reaction times, although inhibition experiments showed that pNPS was able to bind to PP1 with an inhibition constant (Ki) of 40 ± 9 mM.

A closer inspection of the two enzyme active sites highlights several differences between AP and PP1 that might be relevant to the distinct catalytic characteristics. In AP, the two native metal ions are Zn2+, which are separated by 4.0 Å in the available crystal structures;30 the ligands of the zinc ions include three carboxylates, three histidines and one deprotonated serine as the nucleophile. In PP1, there are debates regarding the identity of native metal ions. Peti et al.31 suggested that PP1 can be expressed with many different metals, including Zn2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Fe2+ and Mn2+, while it exhibits the highest levels of activity and stability with Mn2+. More recently, Heroes et al.32 and Salvi et al.33 suggested that native PP1 is associated with Fe2+ and Zn2+, while the recombinant PP1 contains two manganese ions. When expressed in E. coli, such as in the crystal structure 4MOV shown in Fig. 1, the metal ions are Mn2+; they are separated by a short distance of 3.1 Å due to the bridging hydroxide. The ligands include two carboxylates, three histidines, one water, one asparagine and one bridging hydroxide as the nucleophile. Therefore, it appears that the PP1 bimetallic site features a higher positive charge density (without considering the substrate), although the AP active site also contains a Mg2+, which shares a carboxylate with one of the zinc ions while being bound to another carboxylate. Whether the distinct catalytic characteristics of AP and PP1 are largely determined by the different electronic structures of Zn2+ and Mn2+ (d10 vs. d5), or by the different metal-metal distances, or by the different distributions of charged and polar residues in the active site remain to be better clarified.

In this work, we aim to provide mechanistic insights into the discussed differences between AP and PP1 using computational studies. Although hybrid Quantum Mechanical/Molecular Mechanical (QM/MM) simulations34–41 have been productive for AP42–44 and related enzymes,45,46 such calculations remain technically challenging for PP1, which includes open-shell metal ions (Mn2+) and requires extensive sampling due to its open active site. Therefore, in this work we employ the QM cluster model approach, which has been successfully applied to study a fairly broad set of metalloenzymes;47,48 in our recent work,28 cluster calculations have reproduced observed kinetic isotope effects and captured several key trends in the experimental Brønsted plots. The QM cluster model includes a limited set of nearby residues, thus the results should be considered to reflect the intrinsic reactivity of the active site. Comparison of the QM cluster results with experimental observations thus helps distinguish catalytic properties that are largely dictated by the bimetallic site from those that require contributions from more distant residues; this represents a major goal for the current study. In the future, with improved DFTB model for open-shell metal ions49–51 and multi-level free energy methodologies,36,52–57 we will be able to compare QM/MM simulations with the current QM cluster results for additional mechanistic insights.

In the following, we first summarize the computational models and methodologies. We then present the key results and discuss them in the context of available experimental observations. Finally, we draw a few conclusions and offer our perspective on possible future studies.

2. Computational Models and Methods

2.1. The general methodology

The QM cluster model for PP1 is built based on the PDB structure 4MOV,58 which is for the enzyme expressed in E. coli. The cluster model (see Fig. 1, generated by using UCSF Chimera program59) includes the following groups in the active site: the two Mn2+ ions, the bridging hydroxide ion, Asp64, His66, Asp92, Asp95, Arg96, Asn124, His125, Asn131, His173, Arg221, His248 and Tyr272; the total charge for the system including the substrate is +1. The total number of atoms is in the range of 153 to 159 depending on the substrate, which includes (see Scheme 1) seven arylphosphates with the leaving group pKa ranging from 7 to 11: para-nitrophenyl (pNPP), para-chlorophenyl (pCLPP), meta-chlorophenyl (mCLPP), meta-cyanophenyl (mCNPP), para-cyanophenyl (pCNPP), para-methylphenyl (pMPP) and phenyl (PP). The QM model for AP is built based on the PDB structure 1ED830 and also shown in Fig. 1; it includes two Zn2+ ions, the nucleophile Ser102, Asp51, Arg166, Asp327, His331, Asp369, His370 and His412, and we study the same set of substrates listed above.

During the calculations, most of the enzymatic side chains are truncated at their β-carbon, which were converted to methyl groups. The β-carbon atoms are fixed to their crystallographic positions to mimic the enzyme environment and to prevent unrealistic distortion of the cluster during geometry optimization. For Arg96 and Arg221 in PP1, to limit the size of the QM region and ensure sufficient flexibility, the frozen atom is selected to be the δ-carbon. For Arg166 in AP, however, to allow larger displacements of the side chain for stabilizing the leaving group during the reaction, the frozen atom is selected to be Cβ rather than Cδ. With this structural flexibility, Arg166 can potentially adopt two different orientations to stabilize the transition state: it can form two hydrogen bonds with the phosphate group without directly interacting with the leaving group, or it can form one hydrogen bond with the phosphate and another hydrogen bond with the leaving group (see Fig. S6). Calculations shown in the Supporting Information (Fig. S6) indicate that the former orientation is energetically more favorable, due likely to the large negative charge of the phosphate group; this is consistent with findings from recent QM/MM simulations from our research group.42,44 In the following, we will focus on results obtained with this orientation of the Arg166 sidechain.

All quantum mechanical calculations are performed using the Gaussian 16 program.60 Geometry optimizations are performed using the Becke, three-parameter, Lee-Yang-Parr exchange-correlation functional (B3LYP61–63) with the addition of Grimme’s third version semi-empirical dispersion correction (D364,65). The Def2TZVP basis set66,67 are used for the Mn2+ ions and the 6–31G(d,p) basis set68–70 is used for the other atoms (C, O, P, S, N, Cl and H) during geometry optimization and vibrational analysis. All geometry optimizations are performed with the conductor-like polarizable continuum solvation model (CPCM)71,72 with a dielectric constant of 4.0 to approximately account for the missing protein environment; test calculations using higher dielectric constants (ϵ = 12, 20) did not change the nature of the transition in our previous study.28 Discussions on computational benchmarks and the optimized coordinates for all species involved in the reaction are included in the Supporting Information.

2.2. Treatment of metal ions

There are five electrons in the 3d orbitals of Mn2+. Thus, on each Mn2+ ion, the spins can be ferromagnetically or antiferromagnetically coupled, which lead to a total spin of S = 10/2 and S = 0, respectively. With the arylphosphate substrates, the antiferromagnetic coupling state is ~0.6 kcal/mol lower than the ferromagnetically coupled state (see Table S5 in Supporting Information); similarly, the effects of antiferromagnetic coupling on the geometry are also small (see Table S6 and Figure S2). Therefore, the ferromagnetically coupled state (S=10/2) is studied throughout the rest of the study due to the more rapid SCF convergence. This choice, along with other methodological details, is supported by the close agreement between optimized reactant state structure with the crystal structure (see Table S6); for example, the Mn2+-Mn2+ distance with phenyl phosphate as the substrate is optimized to be 3.17 Å, as compared to the value of 3.14 Å in the crystal structure with bound inorganic phosphate.

The metal ions in the active site of PP1 are Mn2+, while they are Zn2+ in AP. To probe the effects of metal ions’ electronic structure on the reactivity and transition state structure, we have also constructed QM cluster models for PP1 and AP with swapped metal ions; i.e., with Zn2+ ions in PP1 and Mn2+ in AP. As Mn2+ ions feature a larger coordination number than Zn2+ ions, there are non-negligible structural perturbations upon metal ion swap, especially for PP1. As shown in Figure S4, upon substituting Zn2+ ions into PP1, a water molecule originally bound to Mn2+ dissociates. To establish whether this has any major impact on the reactivity, a smaller PP1-Zn model (denoted as PP1-Zn-SM in the paper) without the water molecule and the nearby Tyr272 residue is also studied. Although these calculations with local minimizations clearly only capture a limited degree of protein response to metal substitution, they serve the purpose in this study as they likely reflect the intrinsic difference between the metal ions in the absence of extensive structural reorganization.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Polarization of P-Olg Bond in the Reactant (Ground) State

We start by comparing the structural features of different substrates in the two enzyme active sites. In particular, we compare the degree that the P-Olg bond gets polarized and elongated; the reference structures of the seven substrates optimized in water (solvated by 20 explicit water molecules and the CPCM model with a dielectric constant of 78.35, as shown in Figure S3.) are summarized in the Supporting Information. As shown in Fig. 2, the P-Olg bond length is linearly correlated to the leaving group pKa with an R2 value of 0.93, 0.94 and 0.98 for the substrates in water, PP1 and AP, respectively; increase of the leaving group pKa leads to a decrease of P-Olg equilibrium bond distance, although the effect is relatively modest and, in a given environment, spans a range of less than 0.05 Å for the substrates studied here. The equilibrium P-Olg bond length in water is shorter than that in the PP1 and AP models; for example, the optimized P-Olg bond length of pNPP is 1.70 Å in water, while the distance is increased to 1.77 Å and 1.74 Å upon binding to the active site of PP1 and AP, respectively, indicating polarization of the scissile bond. It is worth noting that it is essential to include a number of explicit water molecules for the substrate in water. As shown in Table S7, for example, the optimized P-Olg bond length of pNPP is 1.85 Å with CPCM only, while it is reduced to 1.82 Å, 1.80 Å and 1.70 Å upon the inclusion of one, two and twenty explicit water molecules, respectively.

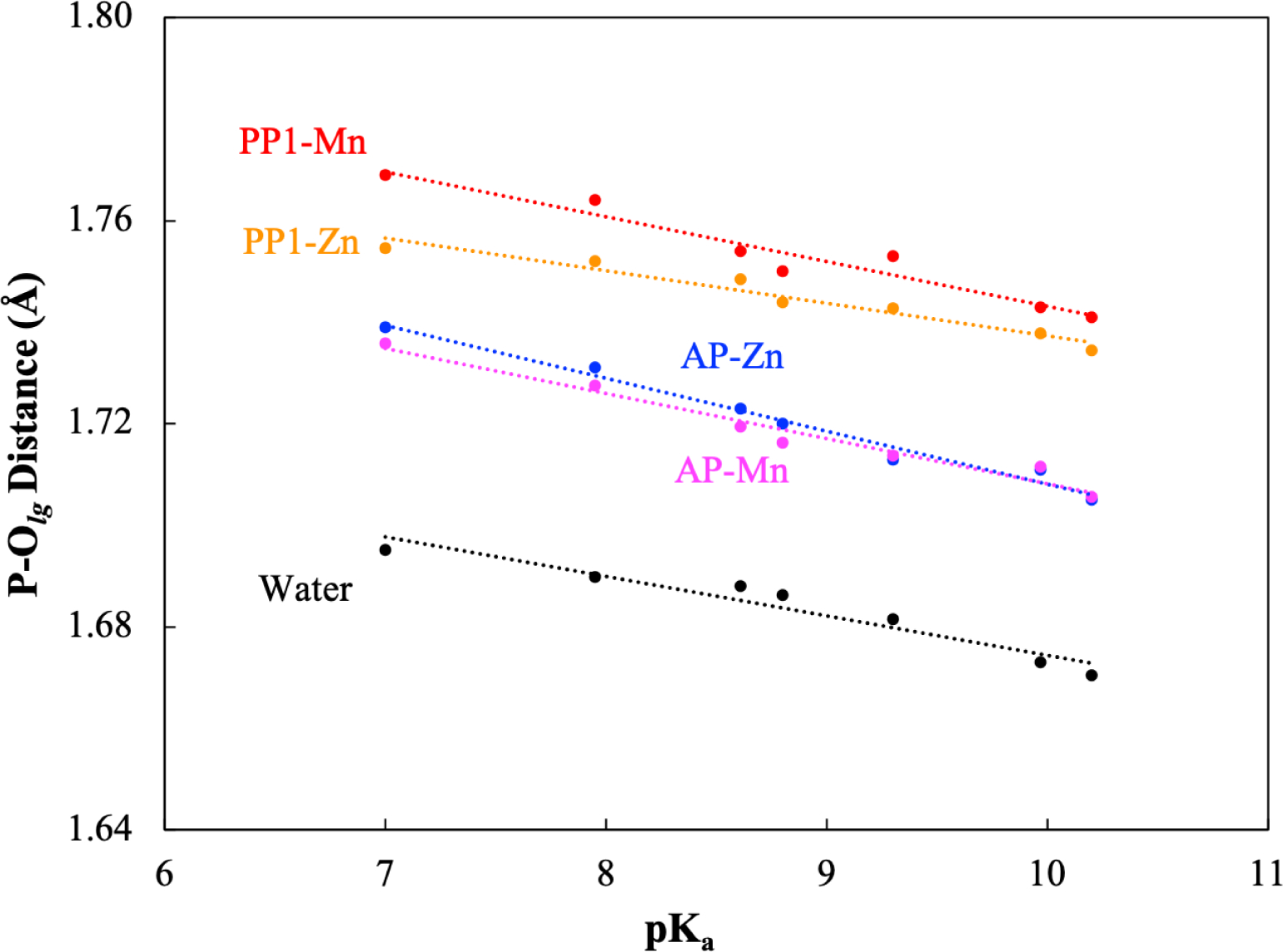

Figure 2:

The optimized substrate P-Olg bond distances in PP1 and AP, as compared to water; also shown are results for QM cluster models of PP1 and AP with swapped metal ions. The P-Olg bond is polarized and thus longer in length in the enzyme active sites. For the optimization in water, the substrate is solvated with twenty explicit water molecules (see Fig. S3), with the bulk water descried with CPCM.

Another observation is that the P-Olg distance in PP1 is systematically longer than that in AP. To investigate whether this is due mainly to the different metal ions or protein residues, we also analyze the optimized P-Olg distance in enzyme models with swapped metal ions. As also shown in Fig. 2, while substituting Mn2+ with Zn2+ indeed reduces the equilibrium P-Olg distance in PP1 by ~0.01 Å, the systematic difference between PP1 and AP remains. Therefore, the nature of the metal ions has limited impact on the equilibrium P-Olg distance, while nearby charged residues, such as the Arginine side chains that hydrogen-bond with the phosphate, may play more significant roles; the phosphate group in PP1 is stabilized by two Arginine residues, while there is only one Arginine stabilizing the phosphate group in AP.

3.2. Structure and Bonding of Transition State

Next, we compare key structural features of the phosphoryl transfer transition state in the two enzyme models; these include the lengths of the breaking (P-Olg) and forming (P-Onuc) bonds as well as their sum, which is commonly referred to as the “tightness coordinate” of the transition state.43 These key distances for the different substrates are summarized in Table 1; they are also plotted in Fig. 3 for visual comparisons, and selected structures are also shown in Fig. 4.

Table 1:

Computed transition state properties: distances (d, in Å) and fractional bond orders (fBOa) of P-Olg and P-Onuc.

| AP-Zn | PP1-Mn | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-Onuc | P-Olg | Tightnessc | P-Onuc | P-Olg | Tightnessc | ||||||||

| pNPP | 7.0 | 2.33 | 0.31 | 1.91 | 0.73 | 4.25 | 1.04 | 2.19 | 0.42 | 2.10 | 0.54 | 4.29 | 0.96 |

| pCNPP | 8.0 | 2.25 | 0.38 | 1.91 | 0.73 | 4.16 | 1.11 | 2.18 | 0.43 | 2.09 | 0.54 | 4.27 | 0.97 |

| mCNPP | 8.6 | 2.16 | 0.46 | 1.92 | 0.71 | 4.08 | 1.17 | 2.16 | 0.45 | 2.08 | 0.54 | 4.24 | 0.99 |

| mCLPP | 8.8 | 2.17 | 0.46 | 1.90 | 0.73 | 4.07 | 1.18 | 2.14 | 0.47 | 2.08 | 0.54 | 4.22 | 1.01 |

| pCLPP | 9.3 | 2.13 | 0.50 | 1.92 | 0.70 | 4.04 | 1.20 | 2.11 | 0.50 | 2.08 | 0.54 | 4.19 | 1.04 |

| PP | 10.0 | 2.09 | 0.53 | 1.92 | 0.70 | 4.01 | 1.23 | 2.07 | 0.55 | 2.10 | 0.52 | 4.17 | 1.07 |

| pMPP | 10.2 | 2.05 | 0.57 | 1.92 | 0.68 | 3.97 | 1.26 | 2.06 | 0.55 | 2.11 | 0.51 | 4.17 | 1.06 |

| AP-Mn | PP1-Zn | ||||||||||||

| P-Onuc | P-Olg | Tightnessc | P-Onuc | P-Olg | Tightnessc | ||||||||

| pKab | d | fBO | d | fBO | d | fBO | d | fBO | d | fBO | d | fBO | |

| pNPP | 7.0 | 2.39 | 0.26 | 1.89 | 0.75 | 4.28 | 1.02 | 2.21 | 0.36 | 2.08 | 0.68 | 4.29 | 1.04 |

| pCNPP | 8.0 | 2.31 | 0.34 | 1.88 | 0.76 | 4.19 | 1.10 | 2.12 | 0.38 | 1.96 | 0.68 | 4.08 | 1.06 |

| mCNPP | 8.6 | 2.32 | 0.31 | 1.85 | 0.79 | 4.17 | 1.10 | 2.07 | 0.42 | 1.96 | 0.67 | 4.04 | 1.09 |

| mCLPP | 8.8 | 2.28 | 0.34 | 1.86 | 0.77 | 4.14 | 1.12 | 2.04 | 0.44 | 1.98 | 0.65 | 4.02 | 1.09 |

| pCLPP | 9.3 | 2.28 | 0.33 | 1.85 | 0.78 | 4.13 | 1.11 | 2.04 | 0.45 | 1.98 | 0.65 | 4.02 | 1.10 |

| PP | 10.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.99 | 0.49 | 2.01 | 0.61 | 4.00 | 1.10 |

| pMPP | 10.2 | 2.24 | 0.37 | 1.84 | 0.78 | 4.08 | 1.15 | 1.97 | 0.51 | 2.02 | 0.59 | 3.99 | 1.10 |

The fractional bond order (fBO) is given as a fraction of the Wiberg bond order in the transition staterelative to the values for P-Olg and P-Onuc in the reactant state or the product state, respectively.

Experimental pKa values of leaving groups.

Tightness is characterized either by the sum of P-Onuc and P-Olg distances, or the sum of P-Onuc and P-Olg fractional bond orders.

Figure 3:

Comparison of the tightness, P-O distances and fractional bond orders for optimized transition states structures in PP1-Mn and AP-Zn QM cluster models.

Figure 4:

Superposition of the transition state structures in PP1-Mn(purple)/Zn(green) and AP-Mn/Zn with pNPP (tan) and pMPP (cyan) as substrates: the metal ions plays a major role in modulating the sensitivity of the transition state structure to variation in the leaving group.

Regarding the AP transition state structure, a proposed experimental model based on the crystal structure of vanadate73 is that one of Zn ions coordinates with the scissile phosphate ester oxygen atom. As discussed in our previous work,43 the vanadate structure better reflects the situation for poor leaving groups. For the current set of substrates with leaving group pKa values below 11, the leaving group is not coordinated with the zinc ions, in agreement with our previous QM/MM studies on AP with similar substrates.42,44,74,75

For the P-Olg distance, there is no significant change as the leaving group pKa varies for both PP1 and AP (Fig. 3a); the distances in PP1 are generally longer than those in AP by ~0.2 Å. By contrast, the P-Onuc distance decreases linearly as the leaving group pKa increases (Fig. 3b); as a result, the tightness coordinate also decreases as a function of leaving group pKa (Fig. 3c). The slopes are steeper for AP than PP1, suggesting larger differences in transition state structures for the different substrates in AP. For example, for pNPP and pCNPP, which have a leaving group pKa of 7.0 and 8.0, respectively, the P-Onuc distances in the transition state are 2.19 Å and 2.18 Å respectively, in PP1; the corresponding values are 2.33 Å and 2.25 Å respectively, in AP. The distinct degrees of structural difference also translate into different magnitudes of barrier height variations. As shown in Tables S8 and S11 in the Supporting Information, the barrier difference between pNPP and pCNPP is merely 0.9 kcal/mol (9.7 and 10.6 kcal/mol, respectively) in PP1, while the difference is 4.2 kcal/mol (10.5 and 14.7 kcal/mol, respectively) in AP.

In addition to structure and energetics, we also characterize the transition state by the bond orders of the forming and breaking bonds, similar to our recent QM/MM studies of AP.42,44 Specifically, we report the fraction of the Wiberg bond orders76 for the breaking and forming bonds in the transition state relative to their values in the reactant and product states, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the general trend for both enzymes is that, with increasing leaving group pKa, the P-Olg bond order is lower and the P-Onuc bond order is higher in the transition state; i.e., the transition state is later in nature, in agreement with expectation from the Hammond postulate. The magnitude of bond order change with different leaving groups, however, differ between the two enzyme models. In PP1, the fractional bond orders for P-Olg with different substrates are similar, with the maximum value of 0.54 for pNPP and the minimum value of 0.51 for pMPP; the fractional bond orders for the P-Onuc exhibit somewhat larger changes, with the maximum value of 0.55 for pMPP and the minimum value of 0.42 for pNPP. For AP, the variation is more significant, especially for P-Onuc: the maximum value is 0.57 for pMPP and the minimum value is 0.31 for pNPP; for P-Olg, as expected based on trend in the bond distance, the bond order in AP is generally higher than PP1 by ~0.2, indicating a lower degree of bond cleavage in the transition state.

The “tightness” of the transition state can be characterized by the sum of the P-Olg and P-Onuc bond orders. The value can be used to classify the transition state structures into three regions: loose, synchronous, and tight, which feature the tightness bond order of < 0.9, [0.9,1.1] and > 1.1, respectively.43 As shown in Fig. 3d, all PP1 transition states structures studied here fall into the synchronous region, with both P-Olg and P-Onuc fractional bond orders ~0.5. For AP, two cases fall into the synchronous region, while all others are in the tight region, where P-Olg bond has a high fractional bond order ~0.7 with a fractional bond order of ~0.5–0.6 for P-Onuc.

Taken together, the structural, energetic and bond-order analyses observed here support the notion that PP1 stabilizes similar, synchronous transition state structures for phosphate esters with different leaving groups, while AP accommodates transition states of more diverse nature, as shown in Fig. 4; the latter is consistent with findings of previous QM/MM simulations from our group.42,44,75 Moreover, the degree of P-O bond cleavage in AP is systematically lower in the transition state than PP1.

3.3. Effects of the Metal Ions on Transition State Properties

The observations from the last subsection beg the question of whether the different properties of transition states in PP1 and AP are mainly due to the different metal ions or distribution of protein residues in the two enzyme active sites. To gain insights into this question, we examine the properties of enzyme models with swapped metal ions.

Bond order analysis (see Table 1) indicates that Zn2+ substitution into PP1 models leads to less bond cleavage but somewhat smaller effects on P-Onuc, thus shifting the nature of the transition state towards the tight region (Fig. 5a); moreover, larger variations in P-Olg bond order are also observed. Conversely, swapping Mn2+ into the AP model reduces the range of bond order variations in transition state structures with different leaving groups, especially regarding P-Onuc; the transition states in AP-Mn are generally earlier in nature than AP-Zn (Fig. 5b). Another observation is that the distances between two Mn2+ ions are shorter than those between two Zn2+ ions in both PP1 and AP, as shown in Table S15, S17, S21 and S24. The substitution of Mn2+ with Zn2+ in PP1 leads to elongation of the metal-metal distances by about 0.03 Å (see Fig. 4a and Fig. 4c). In AP, since the metal-metal distance is longer than that in PP1, the substitution of Zn2+ with Mn2+ shortens the metal-metal distance more significantly by about 0.20 Å (see Fig. 4b and Fig. 4d). These observations indicate that the identity of the metal ion plays a major role in determining the transition state properties, including their variation with respect to the nature of the leaving group.

Figure 5:

Metal ion effects on the transition state structures in PP1 and AP using metal-swapped QM cluster models.

It is worth noting that the reaction barriers of the enzyme models are clearly affected by metal substitution. Curiously, for both PP1 and AP, substitution of non-native metal ions into the active site actually reduces the potential energy barrier, as shown in Tables S8–S12, although the magnitude of reduction is modest and on the order of a few kcal/mol. These trends are not expected considering that experimental studies of PP1 expressed with different metal ions (Zn2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Fe2+ and Mn2+) consistently found the highest levels of activity and stability with Mn2+ ions. For AP, experimental studies have shown that substitution of Zn2+ by Mn2+ produced an enzyme with far less activity.77,78 For example, for the hydrolysis of pNPP in AP, Mn2+ substituted AP has a turnover number of 0.2 s−1,78 while the wild-type enzyme has a kcat value of 30 s−1.79 Therefore, the computed absolute reaction barriers highlight the limitation of the QM cluster model, which captures only limited structural relaxations upon metal substitution (see Fig. S4–5). On the other hand, the observation of strong correlations between computed properties and leaving group pKa suggests that the cluster model is able to capture key trends among a series of substrates.

3.4. Approximate Brønsted Relationship

Based on the calculated potential energy barriers (ΔE‡) and thermal correction based on harmonic vibrational analysis, we have estimated the activation free energies and the Brønsted slope using the familiar transition state expression for kcat; in computing βlg, experimental pKa values for the leaving groups are used. Using the same harmonic approxiation, we have also estimated the equilibrium Brønsted relation and therefore βlg/βEQ,lg; the values are summarized in Table 2, together with available experimental data.

Table 2:

Computed βlg, βEQ,lg and their ratios in comparison to the experimental data.

| Calculation | Experimental | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System | βlg | βEQ,lg | ratio | βlg | βEQ,lg | ratio |

| PP1-Mn | −0.87 | −1.68 | 0.52 | −0.3219 | – | – |

| PP1-Zn-LM | −0.99 | −2.47 | 0.40 | – | – | – |

| PP1-Zn-SM | −0.69 | −2.06 | 0.33 | – | – | – |

| AP-Zn | −1.34 | −3.33 | 0.40 | −0.85a (−0.77b) | – | – |

| AP-Mn | −1.87 | −2.95 | 0.63 | – | – | – |

| −2.09c | −1.72c | 1.21 (0.85)c | −1.2319 | −1.3519 | 0.91 | |

| −1.86 | −2.45 | 0.76 | – | – | – | |

For PP1, the computed value of −0.87 deviates significantly from the experimental value of −0.32;19,25 as discussed in our previous work,28 this discrepancy can have several origins, including the neglect of substrate binding in our calculations, overestimate of βEQ,lg by the cluster model, which doesn’t favor a general acid catalysis mechanism by His125. The computed βlg/βEQ,lg value of ~0.5 falls in a sensible range, suggesting a synchronous transition state; relative to solution, both experiment and our calculation suggest that the transition in PP1 is earlier in nature with less P-Olg cleavage. For AP, both experiment and our calculation point to a higher (more negative) βlg value than in PP1, although the measured values are for alkyl phosphates and aryl O-phosphorothiotes,80 since the chemical step is not rate-limiting in the WT enzyme. However, the computed βlg/βEQ,lg value for AP is 0.40, which seems to suggest an early transition state in terms of P-O cleavage; this clearly is at odd with the computed fractional bond orders for P-Olg in Table 1, which are ~0.7.

Upon metal substitution, for PP1-Zn, the computed βlg/βEQ,lg value decreases in magnitude, suggesting an earlier transition state; this is consistent with the computed fractional bond orders in Table 1. For AP-Mn, however, this correlation breaks down again; the computed βlg/βEQ,lg value is higher for AP-Mn than AP-Zn, yet the fractional bond orders for P-Olg in the transition state are consistently higher for AP-Mn. Therefore, it appears that βlg/βEQ,lg generally correlates with the P-Olg bond order in PP1,28 but not in AP, regardless of the metal ions in the active site with the current cluster model.

3.5. Charges and Transition State structures

To elucidate the nature of transition state, it is useful to analyze the charges on key atoms involved in the reaction, i.e. Onuc and Olg. The natural charges obtained from NBO population analysis81 are used. The charges for PP1 and AP with phosphate substrates are included in Table 3 and compared graphically in Fig. 6. For additional data, see Supporting Information.

Table 3:

Comparison of charges of Onuc and Olg in transition state of PP1-Mn/Zn and AP-Zn/Mn.

| pKa | PP1-Mn | PP1-Zn | AP-Zn | AP-Mn | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | LG pKa | Onuc | Olg | Onuc | Olg | Onuc | Olg | Onuc | Olg |

| pNPP | 7.0 | −1.01 | −0.82 | −1.14 | −0.83 | −0.95 | −0.74 | −0.88 | −0.75 |

| pCNPP | 8.0 | −1.01 | −0.83 | −1.13 | −0.83 | −0.95 | −0.76 | −0.88 | −0.76 |

| mCNPP | 8.6 | −1.01 | −0.83 | −1.13 | −0.84 | −0.94 | −0.78 | −0.88 | −0.78 |

| mCLPP | 8.8 | −1.01 | −0.83 | −1.01 | −0.84 | −0.94 | −0.78 | −0.88 | −0.78 |

| pCLPP | 9.3 | −1.01 | −0.84 | −1.12 | −0.84 | −0.94 | −0.78 | −0.88 | −0.78 |

| PP | 10.0 | −1.00 | −0.84 | −1.23 | −0.84 | −0.94 | −0.79 | −0.90 | −0.83 |

| pMPP | 10.2 | −1.00 | −0.84 | −1.11 | −0.84 | −0.94 | −0.79 | −0.87 | −0.79 |

Figure 6:

Comparison of Onuc and Olg charges in the phosphoryl transfer transition states in PP1 and AP with different substrates and metal ion occupation.

In general, the natural charges on Onuc and Olg do not exhibit large variations with respect to the leaving group, in contrast to the corresponding P-O bond distances and bond orders. Compared to AP, PP1 generally features more negative charges on Onuc and Olg in the transition state, either with Mn2+ ion or Zn2+ ion, reflecting the generally different transition state structures in the two enzymes. For example, the Onuc and Olg charge for the case of pNPP are −1.01 e and −0.82 e, respectively, in PP1-Mn transition state, larger in magnitude than the Onuc (−0.95 e) and Olg (−0.74 e) charges in AP-Zn. These differences reflect the strength of interaction between Onuc and Olg and nearby positively charged ions or residues. Specifically, for Onuc, the charges are likely determined by the interaction with the metal ions. As shown in Table 4, the metal-Onuc distances for PP1 are generally longer than AP, indicating weaker interactions that lead to a more negatively charged Onuc. It is interesting in this regard that, within the same enzyme, both PP1 and AP exhibit more negatively charged Onuc when Zn2+ is present in the active site, suggesting that Zn2+ has a weaker coordination to hydroxide than Mn2+. For Olg, its charge is more correlated with the degree of P-Olg cleavage in the transition state; PP1 features higher Olg charges due to the systematically lower P-Olg bond order in the transition state than AP (Table 1). The effect of metal substitution on Olg charge is negligible, as expected.

Table 4:

The metal-Onuc distances (in Å) in transition state of PP1-Mn/Zn and AP-Zn/Mn.

| pKa | PP1-Mn | PP1-Zn | AP-Zn | AP-Mn | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | LG pKa | (Mn2+-Onuc)1 | (Mn2+-Onuc)2 | (Zn2+-Onuc)1 | (Zn2+-Onuc)2 | Zn2+-Onuc | Mn2+-Onuc |

| pNPP | 7.0 | 2.16 | 2.12 | 2.10 | 2.03 | 1.92 | 1.98 |

| pCNPP | 8.0 | 2.16 | 2.13 | 2.11 | 2.08 | 1.93 | 1.99 |

| mCNPP | 8.6 | 2.14 | 2.14 | 2.14 | 2.10 | 1.94 | 1.99 |

| mCLPP | 8.8 | 2.15 | 2.14 | 2.15 | 2.10 | 1.94 | 2.00 |

| pCLPP | 9.3 | 2.18 | 2.13 | 2.14 | 2.11 | 1.94 | 2.00 |

| PP | 10.0 | 2.20 | 2.13 | 2.17 | 2.12 | 1.94 | — |

| pMPP | 10.2 | 2.19 | 2.14 | 2.18 | 2.13 | 1.95 | 2.01 |

3.6. Sulfate Hydrolysis Reactivity

As discussed in Introduction, AP was shown to exhibit a notable level of activity towards sulfate monoester hydrolysis,16,18,29 while PP1 was observed25 to only bind to p-nitrophenyl sulfate (pNPS) but exhibited no hydrolysis activity. In this work, two sulfate substrates, pNPS and p-chlorophenyl sulfate (pCLPS) are used to examine their reactivity in PP1 and AP enzyme models. As shown in Table S27–S28, both PP1 and AP models catalyze the hydrolysis of the sulfate substrates with comparable activity. In fact, for both sulfate substrates, the computed potential energy barrier in PP1 is lower than that for the corresponding phosphate analog by about 1 kcal/mol: it is 8.6 and 9.7 kcal/mol for pNPS and pNPP, respectively, and 11.4 and 10.4 kcal/mol for pCLPS and pCLPP, respectively. For AP, the barrier for pCLPS hydrolysis is also lower (ΔE‡ ~ 8.7 kcal/mol) than that for pCLPP (ΔE‡ ~ 14.5 kcal/mol). These trends are not expected based on available experimental data, suggesting that the QM cluster model might not have captured all key interactions with the substrate. Comparing energetics for sulfate hydrolysis in the two enzyme models, the QM cluster results do point to lower barriers for AP than PP1; e.g., for pCLPS, the ΔE‡ is ~2.7 kcal/mol lower than in PP1. Moreover, the sulfate reaction in AP tends to be exothermic while that in PP1 endothermic. These differences, however, appear too small to account for the significantly different sulfate hydrolysis activities observed for the two enzymes in experimental studies.

3.7. Discussion

In this work, we have studied the structural and energetic features of PP1 and AP catalysis using QM cluster models. While the computational methodology is not quantitative due to limited sampling and inclusion of a relatively small number of enzyme residues (see discussion below), comparing the results for a series of closely related substrates along with different metal ions in the active site have complemented our recent analyses28,42,44 to provide insights into phosphoryl transfers in the two seemingly similar yet distinct enzymes.

3.7.1. Variation of transition state structure with different leaving groups

Our recent DFTB3/MM free energy analysis42 observed that the structure of the phosphoryl transfer transition state in AP changed substantially as the leaving group varied. As the pKa of the leaving group increases (i.e., a poorer leaving group), the degree of P-Olg cleavage in the transition state increases substantially, while the degree of P-Onuc formation also increases; correspondingly, the leaving group switches from being adequately stabilized by water molecules to being coordinated with the active site zinc ion, and this trend was observed for both monoester and diester substrates. In the current work, since only minimization was conducted, variation in the transition state structure for different leaving groups is less significant compared to the QM/MM free energy simulations. Nevertheless, as shown in Table 1, the fractional bond order for P-Onuc in the transition state is observed to vary from ~0.3 to ~0.6 as the pKa of the leaving group varies from 7.0 to 10.2. The variation in the fractional bond order for P-Olg is observed to change only by 0.05 in the current work, although we note that our QM/MM study also observed a large degree of P-Olg cleavage only for very poor leaving groups such as ethanol (pKa=16.0); for example, the fractional P-Onuc and P-Olg bond orders for the transition state with phenol leaving group were 0.50 and 0.96 in the QM/MM simulations, which are comparable to the values of 0.53 and 0.70 with the current QM cluster model.

Therefore, considering that previous and current calculations have used different levels of QM methods (DFTB3 vs. B3LYP) and different degree of conformational sampling (molecular dynamics vs. geometry optimization), the general agreement suggests that the phosphoryl transfer transition state structure in AP is indeed sensitive to the nature of the leaving group. As discussed in our recent work42 and by others,82,83 while such structural variation was, in principle, recognized,20,84 they were often assumed to be insignificant in magnitude84 and thus not explicitly considered in the analysis of free energy relations.

The variation of the transition state structure may lead to significant curvature in the free energy relation, as seen in some experimental data.23 It may also complicate the correlation between Brønsted relation and the electronic structure of the transition. For example, the ratio of βlg and βEQ,lg is often correlated with the degree of charge accumulation and degree of bond cleavage in the transition state;20,21 this was largely supported for phosphate and phosphonate ester reactions in solution and PP1 by our recent computational analysis,28 which also revealed notable deviation in the correlation in some cases due to the cross talk between forming and breaking P-O bonds. In the current study, variation of the transition state structure with different leaving groups is smaller in magnitude in PP1 than AP; for example, the fractional P-Onuc bond order in transition state varies between 0.42 and 0.55 for the different substrates in PP1-Mn, compared to the range of 0.31 and 0.57 for AP-Zn. Correspondingly, the correlation between βlg/βEQ,lg and P-Olg fractional bond order in the transition state is generally valid in PP1 (compare Tables 1 and 2), but not in AP. Therefore, the current study further highlights that correlating Brønsted relations with transition state properties is not always straightforward.83

3.7.2. Effects of Metal Ions

By swapping the metal ions between the PP1 and AP models, we show that the identity of the metal ions plays a major role in modulating the nature of the transition state. In addition to perturbing the charge on Onuc in the transition state (Table 3) through direct metal-Onuc coordination, the identity of the metal ion modulates both the breaking and forming P-O bonds in the transition state, again highlighting the cross talk between these bonds that complicates the interpretation of Brønsted relations.28 Therefore, the electronic structure of the metal ion determines not only absolute barrier of the reaction, but also sensitivity of the transition state to variation in the substrate. Zn2+ and Mn2+ ions feature different ionic radii and chemical hardness, thus they exhibit different binding propensities toward ligands, such as nucleophiles, resulting in transition states of different nature.85 The Mn2+ ion is characterized as hard and prefers hard ligands (e.g., carboxylate or carbonyl oxygens) as well as borderline hard ligand (e.g., nitrogen of the histidine imidazole). By contrast, the Zn2+ ion is characterized as a metal ion of borderline hardness and tends to coordinate with diverse ligands, either hard or soft. Therefore, compared to models with Zn2+, less variation in Onuc charges and metal-Onuc binding distances has been observed for PP1 models with Mn2+, as shown in Table 3 and 4; this is consistent with less variation in the transition state structure for models with Mn2+ (Table 1). This prediction can be tested experimentally by swapping different metal ions into either PP1 or AP and conducting sensitive measurements for a series of phosphate substrates with, for example, kinetic isotope effects studies.26

3.7.3. P-O bond polarization in the ground state is evident in PP1 and AP

It is commonly discussed that the electronic structure of the substrate is perturbed upon binding to the enzyme active site.86–88 This is reflected in, for example, shift in vibrational frequency of P-O bond upon binding.87–89 Our recent QM/MM analysis of isotope effects in AP44 also suggested that the P-O bond in phosphate esters is perturbed upon binding. This is also observed in the current study, which finds that the P-Olg bond is notably longer in the PP1 and AP active sites compared to water; in addition, the slope for the correlation between the P-Olg bond distance and leaving group pKa is similar in the two enzyme active sites (Fig. 2). Therefore, the P-Olg bond is indeed polarized by the PP1 and AP active sites, and the degree of polarization appears larger in PP1 as reflected by the systematically longer bond distances; calculations with swapped metal ions suggest that the difference is likely due to the distinct distributions of residues in the two active sites, rather than the identity of the metal ions. Therefore, while the current results are limited to the PP1 and AP models, they support the notion87–89 that binding of charged substrates in enzyme active sites lead to perturbation of the scissile bond. The explicit energetic consequence for such pre-activation is likely limited, as discussed in our previous work on ATP hydrolysis in myosin;90 the bond elongation does highlight, nevertheless, the favorable electrostatic environment that favors the bond activation process.

3.7.4. Limitations of QM cluster models

The current study employs a QM cluster model because it remains challenging to conduct adequate QM/MM sampling with ab initio or DFT based QM method, which is required for transition metal ions such as Mn2+ in PP1. The advantage of the QM cluster model, on the other hand, is that the results help isolate features that are dictated by the active site, such as the roles of the metal ions and first coordination shell of the substrate. The difference between the QM cluster results and experimental data then highlights the contributions from enzyme motifs not explicitly included and/or fluctuations of the enzyme and nearby solvent.

As discussed in our recent work,28 QM cluster models similar to those used here have reproduced observed kinetic isotope effects and captured several key trends in the experimental Brønsted plots for phosphate and phosphonate ester reactions in water and PP1. Nevertheless, there are several important differences between the current QM cluster results and experiments. First, the absolute βlg values are significantly different from the experimental data; for example, the value is computed to be ~−0.87 for PP1-Mn, while the experimental βlg is −0.32. While part of the difference is likely due to the fact that the experimental βlg was based on kcat/Km while the calculations here consider only the chemical step, it is possible that the nature of transition state is perturbed in finite-temperature QM/MM simulations, especially concerning the possibility of general acid catalysis by His125.19 Similarly, for AP, the calculated βlg (−1.3) is also larger than the experimental value (−0.85) based on kcat/Km for a series of alkyl phosphates.91 Second, the computed activation potential barrier often becomes lower upon metal ion swap in both PP1 and AP models; this is not expected since Mn2+ and Zn2+ are regarded as the native metal ions in PP1 and AP, respectively31,92 despite remaining discussion in the case of PP1.32,33 Third, while the current calculations do find slightly lower activation potential barrier for sulfate in AP-Zn than in PP1-Mn, the barriers for sulfate in both PP1-Mn and AP-Zn are lower than the corresponding phosphate analogs. These results are not consistent with the experimental observations that (i) sulfate binds to but is not reactive in PP1-Mn; (ii) sulfate esters are worse substrates than phosphate esters for AP. Therefore, it is a sobering reminder that modest-size QM cluster models have significant limitations for probing enzyme catalysis, especially for those feature significant promiscuous catalytic activities due to their open active sites, which require significant sampling of surrounding enzyme residues and solvent molecules; whether substantially larger QM cluster models (e.g., with >300 atoms48,93) are able to better capture the key properties is also worth studying.

4. Conclusion

Using QM cluster models, we have compared the catalytic characteristics of PP1 and AP toward a broad range of substrates. Although there are limitations in the computational models, the QM cluster approach is well-suited for probing effects due to the metal ions and active site residues in the immediate neighborhood of the substrate. By comparing the computational results for a range of substrates and for enzyme models with swapped metal ions, we have gained insights into the differences between the two enzymes that feature a rather similar bi-metallic motif as well as the factors that drive such differences.

The most evident difference between PP1 and AP observed here is that the phosphoryl transfer transition states in PP1 is synchronous in nature with a significant degree of P-Olg cleavage, while those in AP are tighter, with a modest degree of P-Olg cleavage and a range of P-Onuc formation. The significant degree of cross talk between the forming and breaking P-O bonds complicates the interpretation of Brønsted relation, especially for AP, for which computed βlg/βEQ,lg does not correlate with the degree of P-Olg cleavage, regardless of the metal ions in the active site. By comparison, the correlation between βlg/βEQ,lg and P-Olg bond order, despite some noted deviations,28 appears more valid in PP1, which generally exhibits less variation in the transition state than AP for a series of phosphate substrates with different leaving groups. Results for computational models with swapped metal ions between PP1 and AP suggest that the metal ions modulate both the nature of the transition state and the degrees of sensitivity of the transition state to the leaving group; Zn2+ is a softer ion and thus its interaction with the substrate is more susceptible to perturbation in the nature of the leaving group. Therefore, the computational analysis provides a plausible explanation for the experimental observation that PP1 appears to favor a single type of synchronous transition state while AP is able to accommodate different types (synchronous and tight) of transition states. In the reactant state, there are also notable differences; the degree of the scissile bond polarization is larger for PP1 than AP, although this difference appears to be largely determined by the active site residues rather than the metal ions. Therefore, both identity of the metal ion and positioning of polar/charged residues in the active site contribute to the unique catalytic characteristics of these enzymes.

Several discrepancies have been observed between the computational results and available experimental data, especially concerning the quantitative value of the Brønsted slope and activity toward metal substitution and sulfate substrate in both PP1 and AP. These observations highlight potential contributions from the heterogeneous and dynamical enzyme environment beyond the homogeneous and static dielectric model used herein. To reveal the relative importance of specific static interactions and thermal fluctuations, hybrid QM/MM simulations with adequate sampling are needed;45 this remains challenging for enzymes such as PP1, which contain open-shell transition metal ions like Mn2+. Further developments of approximate QM methods for transition metal ions50,51 and effective multi-level free energy simulations36,52–57 are sorely needed for gaining deeper insights into the catalytic mechanism of PP1 and other metalloenzymes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH to QC (R01 GM106443). Computational resources from the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by NSF grant number OCI-1053575, are greatly appreciated; part of the computational work was performed on the Shared Computing Cluster which is administered by Boston University’s Research Computing Services (URL: www.bu.edu/tech/support/research/).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

More detailed structural and energetic results for the studied models are included. The cartesian coordinates for optimized structures (reactant, transition state and product) are also included. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- (1).Jencks WP Catalysis in chemistry and enzymology; Dover publications: New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Cleland WW; Hengge AC Enzymatic mechanisms of phosphate and sulfate transfer. Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 3252–3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kraut DA; Carroll KS; Herschlag D Challenges in enzyme mechanism and energetics. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2003, 72, 517–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zalatan JG; Herschlag D The far reaches of enzymology. Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 516–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Andreini C; Bertini I; Cavallaro G; Holliday GL; Thornton JM Metal ions in biological catalysis: from enzyme databases to general principles. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2008, 13, 1205–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lippard SJ; Berg JM Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry; University Science Books: Mill Valley, CA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Wei W-J; Qian H-X; Wang W-J; Liao R-Z Computational understanding of the selectivities in metalloenzymes. Front. Chem 2018, 6, 638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lu Y; Berry SM; Pfister TD Engineering novel metalloproteins: design of metal-binding sites into native protein scaffolds. Chem. Rev 2001, 101, 3047–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lu Y; Yeung N; Sieracki N; Marshall NM Design of functional metalloproteins. Nature 2009, 460, 855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Nanda V; Koder RL Designing artificial enzymes by intuition and computation. Nat. Chem 2010, 2, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).O’Brien PJ; Herschlag D Catalytic promiscuity and the evolution of new enzymatic activities. Chem. & Biol 1999, 4, R91–R105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Copley SD Enzymes with extra talents: Moonlighting functions and catalytic promiscuity. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2003, 7, 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Khersonsky O; Roodveldt C; Tawfik DS Enzyme promiscuity: evolutionary and mechanistic aspects. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2006, 10, 498–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Khersonsky O; Tawfik DS Enzyme promiscuity: a mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2010, 79, 471–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Pabis A; Duarte F; Kamerlin SCL Promiscuity in the Enzymatic Catalysis of Phosphate and Sulfate Transfer. Biochem. 2016, 55, 3061–3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).O’Brien PJ; Herschlag D Sulfatase activity of E-coli alkaline phosphatase demonstrates a functional link to arylsulfatases, an evolutionarily related enzyme family. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 12369–12370. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Jonas S; Hollfelder F Mapping catalytic promiscuity in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Pure Appl. Chem 2009, 81, 731–742. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lassila JK; Herschlag D Promiscuous Sulfatase Activity and Thio-Effects in a Phosphodiesterase of the Alkaline Phosphatase Superfamily. Biochem. 2008, 48, 12853–12859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).McWhirter C; Lund EA; Tanifum EA; Feng G; Shelkh QI; Hengge AC; Williams NH Mechanistic study of protein phosphatase-1 (PP1), a catalytically promiscuous enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 13673–13682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Williams A Free energy relationships in organic and bio-organic chemistry; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lassila JK; Zalatan JG; Herschlag D Biological phosphoryl transfer reactions: Understanding mechanism and catalysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2011, 80, 669–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hollfelder F; Herschlag D The nature of the transition-state for enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer - hydrolysis of o-aryl phosphorothioates by alkaline-phosphatase. Biochem. 1995, 38, 12255–12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zalatan JG; Herschlag D Alkaline phosphatase mono- and diesterase reactions: Comparative transition state analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 1293–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Duarte F; Barrozo A; Aqvist J; Williams NH; Kamerlin SCL The Competing Mechanisms of Phosphate Monoester Dianion Hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 10664–10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Chu Y; Williams NH; Hengge AC Transition states and control of substrate preference in the promiscuous phosphatase PP1. Biochem. 2017, 56, 3923–3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hengge AC Isotope effects in the study of phosphoryl and sulfuryl transfer reactions. Acc. Chem. Res 2002, 35, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zalatan JG; Catrina I; Mitchell R; Grzyska PK; O’Brien PJ; Herschlag D; Hengge AC Kinetic isotope effects for alkaline phosphatase reactions: Implications for the role of active-site metal ions in catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 9789–9798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lai R; Cui Q What Does the Brønsted Slope Measure in the Phosphoryl Transfer Transition State? ACS Cata. 2020, Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Catrina I; O’Brien PJ; Purcell J; Nikolic-Hughes I; Zalatan JG; Hengge AC; Herschlag D Probing the origin of the compromised catalysis of E-coli Alkaline phosphatase in its promiscuous sulfatase reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 5760–5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Stec B; Holtz KM; Kantrowitz ER A Revised Mechanism for the Alkaline Phosphatase Reaction Involving Three Metal Ions. J. Mol. Biol 2000, 299, 1303–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Peti W; Nairn AC; Page R Structural basis for protein phosphatase 1 regulation and specificity. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 596–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Heroes E; Rip J; Beullens M; Van Meervelt L; De Gendt S; Bollen M Metals in the active site of native protein phosphatase-1. J. Inorg. Biochem 2015, 149, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Salvi F; Trebacz M; Kokot T; Hoermann B; Rios P; Barabas O; Köhn M Effects of stably incorporated iron on protein phosphatase-1 structure and activity. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 4028–4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Warshel A; Levitt M Theoretical Studies of Enzymic Reactions - Dielectric, Electrostatic and Steric Stabilization of Carbonium-Ion in Reaction of Lysozyme. J. Mol. Biol 1976, 103, 227–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Field MJ; Bash PA; Karplus M A Combined Quantum-Mechanical and Molecular Mechanical Potential for Molecular-Dynamics Simulations. J. Comput. Chem 1990, 11, 700–733. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lipkowitz KB, Boyd DB, Eds. Gao J, In Reviews in Computational Chemistry VII; VCH: New York, 1995; p 119. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Riccardi D; Schaefer P; Yang Y; Yu H; Ghosh N; Prat-Resina X; Konig P; Li G; Xu D; Guo H; Elstner M; Cui Q Feature Article: Development of effective quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) methods for complex biological processes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 6458–6469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Senn HM; Thiel W QM/MM methods for biomolecular systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 1198–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Brunk E; Rothlisberger U Mixed Quantum Mechanical/Molecular Mechanical Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Biological Systems in Ground and Electronically Excited States. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 6217–6263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Cui Q Quantum Mechanical Methods in Biochemistry and Biophysics. J. Chem. Phys 2016, 145, 140901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Zhou Y; Wang S; Li Y; Zhang Y Born-Oppenheimer Ab Initio QM/MM Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Enzyme Reactions. Methods in Enzymol. 2016, 577, 105–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Roston D; Demapan D; Cui Q Leaving Group Ability Affects Transition State Structure for Phosphoryl Transfer in a Single Enzyme Active Site. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7386–7394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Roston D; Cui Q QM/MM Analysis of Transition States and Transition State Analogues in Metalloenzymes. Methods in Enzymol. 2016, 557, 213–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Roston D; Cui Q Substrate and Transition State Binding in Alkaline Phosphatase Exhibited by Computational Analysis of Isotope Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 11946–11957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Berta D; Buigues PJ; Badaoui M; Rosta E Cations in motion: QM/MM studies of the dynamic and electrostatic roles of H+ and Mg2+ ions in enzyme reactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2020, 61, 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Ganguly A; Weissman BP; Giese TJ; Li N-S; Hoshika S; Rao S; Benner SA; Piccirilli JA; York DM Confluence of theory and experiment reveals the catalytic mechanism of the Varkud satellite ribozyme. Nat. Chem 2020, 12, 193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Siegbahn PEM; Himo F Recent developments of the quantum chemical cluster approach for modeling enzyme reactions. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2009, 14, 643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Blomberg MRA; Borowski T; Himo F; Liao RZ; Siegbahn PEM Quantum Chemical Studies of Mechanisms for Metalloenzymes. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 3601–3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Gaus M; Jin H; Demapan D; Christensen AS; Goyal P; Elstner M,; Cui Q DFTB3 Parametrization for Copper: the importance of orbital angular momentum dependence of Hubbard parameters. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2015, 11, 4205–4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Vujovic M; Huynh M; Steiner S; Garcia-Fernandez P; Elstner M; Cui Q; Gruden M Exploring the Applicability of Density Functional Tight Binding to Transition Metal Ions: Parametrization for Nickel with the Spin-polarized DFTB3 model. J. Comp. Chem 2019, 40, 400–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Bannwarth C; Ehlert S; Grimme S GFN2-xTB-An Accurate and Broadly Parametrized Self-Consistent Tight-Binding Quantum Chemical Method with Multipole Electrostatics and Density-Dependent Dispersion Contributions. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2019, 15, 1652–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Warshel A Computer Modeling of Chemical Reactions in Enzymes and Solution; Wiley, New York, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- (53).König G; Hudson PS; Boresch S; Woodcock HL Multiscale free energy simulations: An efficient method for connecting classical MD simulations to QM or QM/MM free energies using Non-Boltzmann Bennett reweighting schemes. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2014, 10, 1406–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Lu X; Fang D; Ito S; Okamoto Y; Ovchinnikov V; Cui Q QM/MM Free Energy Simulations: Recent Progress and Challenges. Mol. Simul 2016, 42, 1056–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Giese TJ; York DM Development of a Robust Indirect Approach for MM → QM Free Energy Calculations That Combines Force-Matched Reference Potential and Bennett’s Acceptance Ratio Methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2019, 15, 5543–5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Ito S; Cui Q Multi-level Free Energy Simulation with a Staged Transformation Approach. J. Chem. Phys 2020, 153, 044115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Ryde U QM/MM calculations on proteins. Methods in Enzymol. 2016, 577, 119–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Choy MS; Hieke M; Kumar GS; Lewis GR; Gonzalez-DeWhitt KR; Kessler RP; Stein BJ; Hessenberger M; Nairn AC; Peti W et al. , Understanding the antagonism of retinoblastoma protein dephosphorylation by PNUTS provides insights into the PP1 regulatory code. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4097–4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Pettersen EF; Goddard TD; Huang CC; Couch GS; Greenblatt DM; Meng EC; Ferrin TE UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of computational chemistry 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji et al. , H. Gaussian 16 Revision C.01. Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford CT. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Becke AD Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Becke AD Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Lee C; Yang W; Parr RG Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Grimme S; Antony J; Ehrlich S; Krieg H A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys 2010, 132, 154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Grimme S; Hansen A; Brandenburg JG; Bannwarth C Dispersion-Corrected Mean-Field Electronic Structure Methods. Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 5105–5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Weigend F; Ahlrichs R Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Weigend F Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Hehre WJ; Ditchfield R; Pople JA Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XII. Further Extensions of Gaussian—Type Basis Sets for Use in Molecular Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys 1972, 56, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Francl MM; Pietro WJ; Hehre WJ; Binkley JS; Gordon MS; DeFrees DJ; Pople JA Selfconsistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII. A polarizationtype basis set for secondrow elements. J. Chem. Phys 1982, 77, 3654–3665. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Frisch MJ; Pople JA; Binkley JS Self-consistent molecular-orbital methods .25. supplementary functions for gaussian-basis sets. J. Chem. Phys 1984, 80, 3265–3269. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Barone V; Cossi M Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar]

- (72).Cossi M; Rega N; Scalmani G; Barone V Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. J. Comp. Chem 2003, 24, 669–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Holtz KM; Stec B; Kantrowitz ER A model of the transition state in the alkaline phosphatase reaction. J. Biol. Chem 1999, 274, 8351–8354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Hou GH; Cui Q QM/MM analysis suggests that Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) and Nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (NPP) slightly tighten the transition state for phosphate diester hydrolysis relative to solution: implication for catalytic promiscuity in the AP superfamily. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 229–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Hou GH; Cui Q Stabilization of different types of transition states in a single enzyme active site: QM/MM analysis of enzymes in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 10457–10469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Wiberg KB Application of pople-santry-segal cndo method to cyclopropylcarbinyl and cyclobutyl cation and to bicyclobutane. Tetrahedron 1968, 24, 1083. [Google Scholar]

- (77).Coleman JE Structure and mechanism of alkaline phosphatase. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 1992, 21, 441–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Schulz C; Bertini I; Viezzoli MS; Brown III RD; Koenig SH; Coleman JE Manganese (II) as a probe of the active center of alkaline phosphatase. Inorg. Chem 1989, 28, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar]

- (79).Han R; Coleman JE Dependence of the phosphorylation of alkaline phosphatase by phosphate monoesters on the pKa of the leaving group. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 4238–4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).O’Brien PJ; Herschlag D Alkaline phosphatase revisited: Hydrolysis of alkyl phosphates. Biochem. 2002, 41, 3207–3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Reed AE; Weinstock RB; Weinhold F Natural population analysis. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1985, 83, 735–746. [Google Scholar]

- (82).Florian J; Aqvist J; Warshel A On the reactivity of phosphate monoester dianions in aqueous solution: Bronsted linear free-energy relationships do not have an unique mechanistic interpretation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 11524–11525. [Google Scholar]

- (83).Rosta E; Kamerlin SCL; Warshel A On the interpretation of the observed linear free energy relationship in phosphate hydrolysis: A thorough computational study of phosphate diester hydrolysis in solution. Biochem. 2008, 47, 3725–2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Jencks WP A Primer for the BEMA HAPOTHLE - An empirical approach to the characterization of changing transition-state structure. Chem. Rev 1985, 85, 511–527. [Google Scholar]

- (85).Christianson DW; Cox JD Catalysis by metal-activated hydroxide in zinc and manganese metalloenzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem 1999, 68, 33–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Warshel A Electrostatic origin of the catalytic power of enzymes and the role of preorganized active sites. J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273, 27035–27038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Andrews LD; Deng H; Herschlag D, Isotope-edited FTIR of alkaline phosphatase resolves paradoxical ligand binding properties and suggests a role for ground-state destabilization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 11621–11631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Andrews LD; Fenn TD; Herschlag D, Ground State Destabilization by Anionic Nucleophiles Contributes to the Activity of Phosphoryl Transfer Enzymes. PloS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Klahn M; Schlitter J; Gerwert K Theoretical IR spectroscopy based on QM/MM calculations provides changes in charge distribution, bond lengths, and bond angles of the GTP ligand induced by the Ras-protein. Biophy. J 2005, 88, 3829–3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Yang Y; Cui Q The hydrolysis activity of Adenosine triphosphate in myosin: a theoretical analysis of anomeric effects and the nature of transition state. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 12439–12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).O’Brien PJ; Herschlag D Does the active site arginine change the nature of the transition state for alkaline phosphatase-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer? J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 11022–11023. [Google Scholar]

- (92).Plocke DJ; Levinthal C; Vallee BL Alkaline phosphatase of Escherichia coli: a zinc metalloenzyme. Biochem. 1962, 1, 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Sheng X; Kazemi M; Zadlo-Dobrowolska A; Kroutil W; Himo F Mechanism of Biocatalytic Friedel-Crafts Acylation by Acyltransferase from Pseudomonas protegens. ACS Cata. 2020, 10, 570–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.