Abstract

Dublin appears to have performed very well as compared to various scenarios for COVID-19 mortality amongst homeless and drug using populations. The experience, if borne out by further research, provides important lessons for policy discussions on the pandemic, as well as broader lessons about pragmatic responses to these key client groups irrespective of COVID-19. The overarching lesson seems that when government policy is well coordinated and underpinned by a science-driven and fundamentally pragmatic approach, morbidity and mortality can be reduced. Within this, the importance of strategic clarity and delivery, housing, lowered thresholds to methadone provision, Benzodiazepine (BZD) provision and Naloxone availability were key determinants of policy success. Further, this paper argues that the rapid collapse in policy barriers to these interventions that COVID-19 produced should be secured and protected while further research is conducted.

Introduction

There is a well recognised crossover between homelessness and substance dependence. It was recognised early on in the COVID-19 Pandemic that both homeless and drug-using populations were particularly vulnerable to the effects of coronoavirus infection. This is due to the high morbidity burden of these populations; the poor living conditions they experience and their lack of access to health services (Alexander, Stoller, Haffajee & Saloner, 2020; Baggett et al., 2020; Dubey et al., 2020; Kar et al., 2020; López-Pelayo et al., 2020; Marsden et al., 2020; McCann Pineo& Schwartz, 2020; Mosites et al., 2020; Ornell et al., 2020; Reece, 2008; Tobolowsky et al., 2020; Volkow, 2020). For example, Albon et al. feared the congregated nature of hostels could result in 100% transmission rates (Albon, Soper & Haro, 2020). Tobolowsky et al. noted how in a previous SARS-CoV-2 epidemic homeless people were found to suffer an excess burden of infection and warned that interrupting transmission in congregated homeless accommodation was difficult to achieve (Tobolowsky et al., 2020). It was also presumed that there would be increased usage of drugs and higher rates of overdose during the pandemic (Palmer et al., 2012).

When the COVID-19 pandemic reached Dublin, homeless people were therefore identified as a particularly vulnerable group due to their morbidity profile, living conditions and drug use behaviour. A key element of the health services’ strategy to protect homeless people from COVID-19 involved the expansion of harm reduction practices. This resulted in improved access to methadone treatment; improved access to Naloxone; shifting the management of high dose Benzodiazepine (BZD) dependency towards maintenance therapy; and the home delivery of prescription drugs (like methadone and BZDs). Prior to COVID-19 all of these policy choices were limited by regulatory obstacles and uncertain political will. This paper suggests that the response to the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated some of the unnecessary obstacles placed ahead of potentially lifesaving treatments. Further it argues that the COVID-19 policy response has only served to reiterate the value and logic of harm reduction-based drug policies. The purpose of this policy briefing is to outline and explore the Dublin experience and to consider the future policy implications.

The onset of COVID-19 in Ireland

On December 31st, 2019, China alerted the World Health Organisation (WHO) to several cases of unusual pneumonia in Wuhan, a port city in the central Hubei province. In February 2020, the WHO officially named this new Coronavirus ‘COVID-19′ and on 11th March 2020 the WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. On 12th March 2020 schools in Ireland closed to help reduce the spread of COVID-19. Five days later, on 17th March, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar addressed the nation stating that, ‘Never will so many ask so much of so few,’ (Bray, 2020) referring to the people on the front line of the response to COVID-19 in Ireland. Ten days later, on 27th March, at midnight, further restrictions designed to reduce the spread of COVID-19 came into place.

Fear and uncertainty permeated the public and professional consciousness. It was also a time that demanded action. It was clear that the best should not be allowed to become the enemy of the good, and this view – that policy makers must respond quickly and not fear taking risks nor making mistakes – drove much of the policy innovation during this time. This was the message from the Executive Director of the WHO's Health Emergencies Programme, Dr Michael Ryan, when he said:

…if you need to be right before you move you will never win. Perfection is the enemy of the good when it comes to emergency management. Speed trumps perfection and the problem in society we have at the moment is everyone is afraid of making a mistake, everyone is afraid of the consequence of error. But the greatest error is not to move, the greatest error is to be paralysed by the fear of failure…(World Health Organisation, 2020).

This crisis elicited a galvanized response amongst the homeless specialised General Practitioner (GP) services, the harm reduction services and voluntary homeless residential agencies. This was then coordinated by the Social Inclusion, Public Health and Addiction Services of the Health Service Executive (HSE) and Dublin Regional Homelessness Executive (DRHE). The quick overarching coordination helped ensure that specific policy responses moved with speed and clarity and addressed health, housing and substance misuse issues simultaneously. Separate weekly meetings were conductred by the HSE/DRHE with all homeless health providers; all homeless accommodation providers; and all homeless substance misuse providers to ensure a comprehensive and coordinated response.

Housing

At the outset of the policy response there was a very clear sense of what client groups were being targeted. Namely it focused on people who are homeless (Housing Act, 1988), and who use drugs in Dublin city centre, an area with the highest population of these clients (Keane, Collins, Csete & Duffin, 2018). Very early on, the HSE appointed a Clinical Lead for the COVID-19 Homeless Response. Protocols for identification and immediate testing for homeless clients with symptoms were developed and implemented. Accommodation to allow isolation of positive and suspected cases was rapidly obtained by the DRHE and staff were funded by the HSE. Homeless clients who were deemed vulnerable due to age or medical condition were moved to single occupancy accommodation so that they could be shielded from infection. In addition, homeless accommodation with large numbers of residents saw many transferred in order to decrease occupancy levels and thereby to reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19. Close contacts of Covid-Positive cases were placed in quarantine. By early June:

-

•

over 750 symptomatic clients had been tested;

-

•

screening was conducted on 450 asymptomatic residents and 165 asymptomatic staff in hostels where we had positive cases, to assess the level of undiagnosed disease in the sector. Of these 10 residents (2%) and 5 staff (3%) were found to be positive;

-

•

over 330 clients had been placed in isolation (rotating through a 50 bed isolation unit);

-

•

over 500 people had been placed in shielding, of whom 340 were shielded in newly obtained units;

-

•

120 people were moved from high occupancy units to new reduced-occupancy accommodation;

-

•

all rough sleepers were offered accommodation.

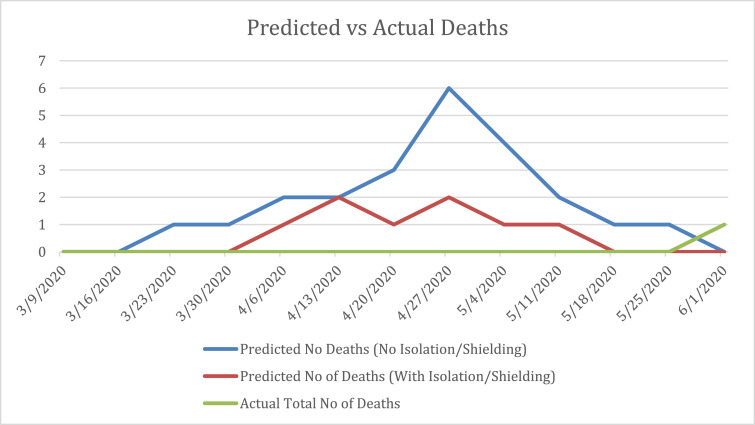

COVID-19 infection and mortality rates were very low with 2% of the Dublin homeless population (63 single homeless people) diagnosed compared to 1% of the general Dublin population. There was only one COVID-19 related death, a fraction of what had been predicted (see Fig. 1 ). The expansion of housing provision seemed to have limited the direct effects of COVID-19 transmission and infection. The infection rates in Dublin (2%) compared favourably to Boston (10%) where shielding units were not developed (Baggett et al., 2020). The above appeared to represent a relatively swift and decisive approach from all sectors with coordination from public servants. Many organisations responded by adapting existing services; redeploying staff; opening new services; and generally took significant personal risks upon themselves and their loved ones to support the response. When these various factors coalesced, decisions that would normally take many months or years were effected within days and weeks.

Fig. 1.

Dublin homeless population: predicted versus actual COVID-19 related deaths between 9th March 2020 and 1st June 2020. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Methadone provision

Correlations between opiate dependence and negative impacts on life expectancy, physical and mental health and social functioning are well documented. The impacts of stigmatising and repressive policies which undermine public health based approaches have a similarly extensive research underpinning them (Csete, 2014, 2016). The benefits of treatment with Opiate Substitution Therapy (OST) for individual users’ health and wellbeing are well recognised. As the WHO states,

Opioid agonist maintenance treatment (OAMT) with long-acting opioids (methadone or buprenorphine), which is combined with psychosocial assistance, is the most effective pharmacological intervention for opioid dependence (UNODC/WHO international standards for the treatment of drug use disorders, 2020, p. 61).

Alongside the gains for individual clients, there are also demonstrable spill over gains from OST for society in general. These include reduced criminal activity, reduced healthcare costs, lower social welfare costs, and improved social functioning (Garcia‐Portilla, Bobes‐Bascaran, Bascaran, Saiz & Bobes, 2014).

It was recognised early on that drug users may face loss of access to supply of drugs and that those on OST may face risks of COVID-19 infection when having their OST dispensed (Dubey et al., 2020; Dunlop et al., 2020; Marsden et al., 2020; Ornell et al., 2020). Thus, it was advised that rapid access to OST and flexibility in delivery of OST were required (Becker & Fiellin, 2020; Dubey et al., 2020; Dunlop et al., 2020; Heimer, McNeil & Vlahov, 2020; Salamat, Hegarty & Patton, 2019). As Khatri wrote “we must provide innovative and “low threshold” paths to treatment for new patients while keeping our existing patients engaged in care” (Khatri & Perrone, 2020).

In Dublin there are two main routes for homeless clients to access OST. First, the National Drug Treatment Centre (NDTC), which is a designated OST service for homeless people from across Ireland. The NDTC is based in Dublin City Centre and is the largest treatment centre in the Republic. Prior to the COVID-19 Crisis the NDTC had circa 550 clients with methadone being dispensed on site. Second, GMQ Medical, which was established as a primary care service for homeless people based out of the Granby and Merchants Quay day services.

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, GMQ Medical had circa 150 clients. However, GMQ Medical had a cap on numbers of patients/hostels it could recruit and NDTC had capacity issues affecting the number of people that they could provide OST to. Due to the large increase in the homeless population in Ireland since the 2007 recession, there has been an imbalance between numbers applying for treatment and those actually being transferred to the community. This resulted in a waiting time for treatment for GMQ Medical of between 12 and 14 weeks. Delayed treatment admission is associated with numerous risks, including higher rates of intravenous drug usage, overdose, blood borne viral infection and increased mortality (Csete et al., 2016). Nationally, waiting times are determined by a combination of the limits placed on client numbers by clinics, the availability of prescribing doctors and the number of community pharmacy places available. If places are unavailable clients are placed on a national waiting list (Health Service Executive, n.d.). Long waiting times for homeless people accessing OST are, of course, not unique to Dublin.

It was quickly recognised that one of the main deterrents to individual compliance with isolation and shielding guidelines was substance use. A large number of patients presented who were heroin dependant and were not availing of OST. Immediately, the HSE issued national contingency guidelines allowing for reduced waiting times and removal of caps on recruitment to treatment (Health Service Executive, 2020) . In addition, other Drug Treatment Clinics agreed to take on homeless patients resident in hostels in their catchment areas. Waiting times dropped overnight from 12 to 14 weeks to 2–3 days. An inpatient unit for rapid initiation on to OST for COVID-19 positive, and suspected, patients was established. This four-bedded unit was set up in one of the new homeless isolation units where it had access to 24-hour nursing care.

In addition, it was recognised that clients both in isolation and shielding facilities, would be exposed to risk if they had to collect their OST and medication at treatment centres or pharmacies. The EMCDDA had already highlighted that “access to medication is likely to be particularly challenging for those self-isolating, under lock down or in quarantine” (EMCDDA, 2020). Supervision guidelines were amended to allow members of the NDTC and two non-governmental organisation (NGO) Harm Reduction services, Ana Liffey Drug Project and Chrysalis Community Drug Team, to collect clients’ OST and other medication and deliver it at intervals dictated by the client's risk of overdose. Other jurisdictions acted similarly to allow patients more flexibility in obtaining take-away dosages. The amount of methadone patients were allowed to take away was to be decided on a case-by-case basis taking into account the client's stability, the presence of chronic medical conditions and the presence of keyworking/nursing supports in their accommodations (De Jong, DeJong-Verhagen, Pols, Verbrugge & Baldacchino, 2020; SAMHSA, 2020).

Thus, the crisis appeared to demonstrate that whatever systemic factors had heretofore maintained long waiting times for OST, the COVID-19 impetus saw them removed overnight. Despite an initial EMCDDA warning that due to the COVID-19 pandemic there was, “a risk of reduced access to opioid substitution therapy and other essential medications” (EMCDDA, 2020) data suggests that waiting times for methadone in Dublin actually reduced. Overall an extra 160 clients were initiated on treatment by GMQ Medical and 44 by NDTC. Of those started by GMQ Medical, 57 had been sleeping rough prior to initiation of treatment. This was a significant improvement in service provision from which broader drug policy lessons in Ireland and indeed potentially around the world can be drawn.

BZD maintenance

There is an increasing problem with high dose BZD dependence both internationally and in Dublin (Darker, Sweeney, Barry & Farrell, 2015; Yamamoto et al., 2019). Up to 66% of patients on OST misuse BZDs (Nielsen, Dietze, Lee, Dunlop & Taylor, 2007). In Dublin, 62% of homeless people on OST also misuse street BZDs. BZDs have been implicated in up to 60% internationally, and in Ireland in 92% and 81% of overdose deaths respectively where methadone or heroin were implicated (Dhalla et al., 2009; Health Research Board, 2017). In Dublin, there is a national guideline for BZD detoxification but none for maintenance treatment (Progression Routes Iniative, 2011). The prescribing of BZDs is controversial due to the recognised deleterious effects of longterm treatment with these drugs (Uzun, Kozumplik, Jakovljević & Sedić, 2010). Existing guidelines on BZDs recommend detoxification (Health Service Executive, n.d.). Patients on OST get offered either a BZD detox or a maintenance course usually depending on individual clinician preference. This is consistent with international practice, where there is no consensus on the most appropriate clinical intervention (Baandrup, Ebdrup, Lindschou, Gluud & Glenthøj, 2015; Liebrenz, Boesch, Stohler & Caflisch, 2010; Soyka, 2010; Tyrer, 2010). The majority of guidelines examined favour gradual detoxification followed by complete abstinence irrespective of the duration and severity of misuse (Lader, Tylee & Donoghue, 2009; Parr, Kavanagh, Cahill, Mitchell & Young, 2009). However, in practice, clinicians working in addiction services that have no formal protocol for BZD maintenance often still end up prescribing long term BZDs (Tjagvad, Clausen, Handal & Skurtveit, 2016).

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, GMQ Medical offered BZD detoxes based on the national protocol, but only offered BZD maintenance in occasional cases where previous detoxes had failed and the client was seen to be at high risk from substance misuse. This approach was influenced by the presence of a clear national policy for BZD detox and an absence of a similar policy for BZD maintenance. As COVID-19 infections started to rise in Dublin and clients were placed in Isolation Units and Shielding Units, it was realised that those with high dose BZD dependence were unlikely to remain in their accommodation so increasing their, and other residents’, risk of infection. National contingency guidelines emerged recommending that patients in isolation could be offered up to 30 mg daily to prevent withdrawals for the period of isolation only. In the homeless sector over 70 people were commenced on BZD maintenance treatment. The homeless sector decided to offer maintenance treatment to patients either in Isolation or Shielding. These medications were collected daily by Ana Liffey Drug Project and Chrysalis Community Drug Team and delivered to the clients in their accommodation.

The homeless health sector met weekly. It was reported at these meetings that the health and behaviour of clients on maintenance had seemed to improve and that they had complied with the isolation/shielding recommendations. As a result, GMQ Medical reviewed their policy on BZDs and decided to offer BZD maintenance treatment to all patients on OST with established BZD dependency. Dependency was established by interviewing the patient, reviewing their urine results and any history of failed BZD detoxes.

A number of clinicians have advocated for maintenance (agonist substitution) treatment for those who have difficulties detoxing or abstaining from BZD misuse (Liebrenz et al., 2010; Wickes, Darke & Ross, 2000). There is evidence supporting the efficacy of this approach (Lingford-Hughes, Welch & Nutt, 2004). Weizman et al. found that 79% of patients placed on a maintenance of Clonazepam remained abstinent for at least one year (Weizman, Gelkopf, Melamed, Adelson & Bleich, 2003). Bakker et al. had been offering BZD maintenance to clients in a GP run methadone clinic in London since 1994. They found those on maintenance had higher treatment retention and lower mortality than patients who had never been or occasionally been prescribed BZDs (Bakker & Streel, 2017). Eibl et al. found that patients who were not prescribed BZDs as part of routine treatment were twice as likely to leave treatment compared to those on maintenance (Eibl, Wilton, Franklyn, Kurdyak & Marsh, 2019). Thus, given this extensive evidence base, GMQ Medical, as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, shifted practice-based policy towards the use of BZD maintenance where clients demonstrated dependency on BZD and wished to have a maintenance treatment.

Naloxone

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist recommended by the WHO for the treatment of opioid overdose (World Health Organisation, 2014). Naloxone is used for the complete or partial reversal of opioid overdose, including respiratory depression. There is a wide body of evidence demonstrating its efficacy (EMCDDA, n.d.). Depending upon the jurisdiction, access to Naloxone varies. Take for example the UK, Ireland's closest English speaking neighbour. In 2005 in the UK, Naloxone was introduced as a medication to be administered, by injection, by anyone for the purpose of saving a life. However, it was classed as a Prescription Only Medicine and was not initially available over the counter but was supplied using a Patient Group Direction (PGD) or in some cases a prescription. In October 2015, there was a regulatory change and it is now much more widely available and accessible without the need for a PGD or prescription (“My 1st 48 hrs out” - Naloxone-on-Release: Guidelines for naloxone provision upon release from prison and other custodial settings, 2018).

Internationally and in Ireland there are relatively more restrictive pathways for accessing Naloxone (Clarke & Eustace, 2016; Larney et al., 2017). In Ireland, this requires a trained keyworker to initially conduct a risk assessment and to educate the client about Naloxone and train them, or their relatives, on how to administer either or both the nasal and injectable forms of Naloxone. Once this is completed the client requires a doctor (usually their own GP, a GP working in specialised homeless services or an OST addiction prescriber) to issue a prescription for the Naloxone. Due to the scheduling of Naloxone in Ireland the person to whom it is prescribed must not give the Naloxone to anyone else to hold for them. However, the HSE did allow for GPs to issue prescriptions retrospectively within a 24 hour period to allow, in particular, for the administration of Naloxone in an overdose scenario (Author's Private Communication, HSE).

With time, it emerged that staff working in homeless services were encountering people who had overdosed, but to whom Naloxone had not been prescribed. It was decided that in these situations, homeless emergency accommodation providers could administer Naloxone as long as the name and date of birth of the person to whom Naloxone was administered was sent to a GP within 24hrs. The GP would then issue a prescription. It was felt that this sufficiently adhered to the regulatory requirements under controlled drug scheduling.

There was a significant concern amongst professionals that people who use drugs, and who were self-isolating in shielding units or isolation units were at a heightened risk of ovedose. On 26th March 2020, National contingency guidelines were published, by the HSE, for anyone who was working with people who use drugs (PWUD). It recognised the urgency of the situation and included guidance on Naloxone, recommending that every individual in receipt of OST and in contact with treatment providers should be offered and encouraged to take a supply of Naloxone. Further it explained that Naloxone was to be administered by a person trained in using the product; and that in the current crisis, injectable Naloxone was to be used. The intranasal product was to be avoided and if using the intranasal product, precautions were to be taken (Health Service Executive, 2020).

Recognising the increased risk of overdose during the COVID-19 crisis the process was quickly adapted to expand access to Naloxone to those most at risk (Health Service Executive, 2020). Naloxone packs were taken out by Ana Liffey Drug Project when delivering their Needle and Syringe Programme (NSP). A person engaging with the outreach NSP was assessed by Ana Liffey Drug Project; who briefed them and/or their partner/companion on the process of using Naloxone and gave them the Naloxone. The names and date of birth were later provided to a GP who issued the prescription for Naloxone retrospectively.

Discussion

A review of the literature found one other similar response to the COVID-19 pandemic that was targeted at homeless people. Boston developed a coordinated approach that included the following elements:

-

•

Front-door symptom screening

-

•

Developing isolation and management venues.

-

•

Exposure Screening, contact-tracing and quarantining of close contacts.

-

•

Real-time surveillance (case tracking).

-

•

Decongestion of crowded hostels into vacant university dormitories .

-

•

Development of a command structure amongst the health professionals involving daily meetings and reviews and also ensuring regular communication with staff working in the sector to respond to emerging issues and allay concerns. This command structure worked with municipal leaders and public health agencies (Baggett et al., 2020).

Due to a high level of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection amongst a number of hostels screened it was decided to abandon symptom screening, exposure screening, quarantining and to reduce contact-tracing. Boston had to expand their COVID-19 care facility from 17 to 52 beds and construct a 500-bed field hospital. Ten percent of the homeless population in Boston were eventually infected (compared to 2% of the general population) (Baggett et al., 2020). Possible reasons why Dublin had better outcomes than Boston include:

-

(i)

Dublin did not abandon its testing and isolation of symptomatic clients;

-

(ii)

The Dublin response involved shielding those who were the most vulnerable clients.

-

(iii)

The population of homeless people in the US may differ from that in Dublin e.g. in terms of numbers of rough sleepers / prevalence of substance misuse / prevalence of physical and/or mental illness.

Both the Boston and Dublin responses involved significant collaboration between homeless housing and health service providers and substance misuse services. This approach incorporates a recognition of the full range of social and medical determinants of health. Of note in Dublin, the Ministers of Health, Housing and Substance Misuse issued a joint statement committing to working collaboratively to address homelessness (Gov.ie, 2020). There were no other examples found in the literature of such a collaborative multi-agency response.

Conclusion

This paper represents a description of a response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the Dublin Homeless Community. While the outcomes, in terms of infection and mortality rates, appear, based on initial results, to be very positive, it is difficult to disentangle the individual impacts of housing, harm reduction and health service provision interventions on these outcomes. Further research seeking to disentangle the effects of these varying factors is recommended. A further limitation is that paper does not include any feedback from the population in question.

This policy briefing highlights three changes to practice during the COVID-19 crisis. Two of those changes (the removal of barriers to rapid access to methadone and the expanded distribution of Naloxone) were such that they resulted in the removal of barriers to the implementation of national policy. The question remains as to why the barriers existed prior to the crisis. The epidemic created an overwhelming public health argument for the facilitation of immediate access to OST and Naloxone. However, a strong public health argument for having no waiting lists for OST and improved Naloxone distribution to PWUD existed prior to and independent of COVID-19. López-Pelayo et al. (2020)) advised that the pandemic provided the opportunity for ameliorating services to drug users and these improvements should be maintained after the pandemic has resolved (López-Pelayo et al., 2020).

It is noteworthy that in the field of Irish medicine the COVID-19 crisis facilitated a number of practice changes that had persuasive arguments in their favour prior to COVID-19 e.g. emailed prescriptions, electronic social welfare certificates, teleconsultations, etc. Why it took a pandemic to overcome barriers to seemingly obvious practice reforms is difficult to discern. Possibilities include the effect of the fear and uncertainty that was palpable as COVID-19 infection spread across the nation; the unification of the health service with a clear single mission i.e. to reduce the transmission of infection; or more controversially, the fact that the public health arguments in favour of harm reduction related mainly to the protection of PWUD whereas the public health arguments that arose during the COVID-19 crisis related to protecting the public at large.

Meanwhile, the shift of some services to using BZD maintenance resulted from the gathering of observations from field workers combined with a review of the evidence concerning BZD maintenance. This has resulted in a change in practice that requires ongoing evaluation.

In summary, the COVID-19 crisis appears to have acted as a catalyst for changes in the delivery of harm reduction measures to homeless PWUD. Some of these changes seemed to move further towards enabling the full implementation of national policy objectives in relation to OST and Naloxone interventions and the expansion of BZD maintenance treatment for patients with high dose BZD dependency. We recommend that practices continue to deliver on OST and Naloxone policy objectives and that policy makers review the evidence on BZD maintenance treatment. We further encourage international jurisdictions to examine the case study highlighted here to see if there are any lessons relevant for their immediate efforts to reduce COVID-19 transmission and save lives. Longer-term, we view the COVID-19 experience as a potentially important milestone in the development of national drug policies, albeit one which will require much further study.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Albon D., Soper M., Haro A. Potential implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on the homeless population. Chest. 2020;158(2):477–478. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander G.C., Stoller K.B., Haffajee R.L., Saloner B. An epidemic in the midst of a pandemic: Opioid use disorder and COVID-19. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020;173(1):57–58. doi: 10.7326/M20-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baandrup L., Ebdrup B.H., Lindschou J., Gluud C., Glenthøj B.Y. Pharmacological interventions for benzodiazepine discontinuation in chronic benzodiazepine users. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;2015(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggett T.P., Racine M.W., Lewis E., De Las Nueces D., O'Connell J.J., Bock B., & Gaeta, J.M. Addressing COVID-19 Among people experiencing homelessness: Description, adaptation, and early findings of a multiagency response in Boston. Public Health Reports (1974) 2020;135(4):435–441. doi: 10.1177/0033354920936227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A., Streel E. Benzodiazepine maintenance in opiate substitution treatment: Good or bad? A retrospective primary care case-note review. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2017;31(1):62–66. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker W.C., Fiellin D.A. When epidemics collide: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the opioid crisis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020;173(1):59–60. doi: 10.7326/M20-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray J. Coronavirus: varadkar addresses nation and says crisis may last months. The Irish Times. 2020, March 17 https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/coronavirus-varadkar-addresses-nation-and-says-crisis-may-last-months-1.4205373 [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A., Eustace A. Health Service Executive; Dublin, Ireland: 2016. Evaluation of the hse naloxone demonstration project.www.drugsandalcohol.ie/26037/1/Naloxonedemoproject.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Csete J. In: Ending the drug wars: Report of the lse expert group on the economics of drug policy. Collins J., editor. LSE IDEAS; London, England: 2014. Costs and benefits of drug-related health services. [Google Scholar]; http://www.lse.ac.uk/IDEAS/publications/reports/pdf/LSE-IDEAS-DRUGS-REPORT-FINAL-WEB01.pdf

- Csete J. In: After the drug wars: Report of the lse expert group on the economics of drug policy. Collins J., Soderholm A., editors. LSE IDEAS; London, England: 2016. Public health research in a time of changing drug policy: Possibilities for recovery?http://www.lse.ac.uk/IDEAS/publications/reports/pdf/LSE-IDEAS-After-the-Drug-Wars.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Csete, J., Kamarulzaman, A., Kazatchkine, M., Altice, F., Balicki, M., Buxton, J., Cepeda, J., Comfort, M., Goosby, E., Goulão, J., Hart, C., Kerr, T., Lajous, A. M., Lewis, S., Martin, N., Mejía, D., Camacho, A., Mathieson, D., Obot, I., & … et al.Beyrer, C. (2016). Public health and international drug policy. The Lancet. Vol 387 p.1427–1480. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00619-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Darker C.D., Sweeney B.P., Barry J.M., Farrell M.F. Psychosocial interventions for benzodiazepine harmful use, abuse or dependence. Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group. 2015;(5):1–91. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong C., DeJong-Verhagen J., Pols R., Verbrugge C., Baldacchino A. Psychological impact of the acute COVID-19 period on patients with substance use disorders: We are all in this together. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience. 2020;11(2):207–216. doi: 10.32598/bcn.11.covid19.2543.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla I.A., Mamdani M.M., Sivilotti M.L.A., Kopp A., Qureshi O., Juurlink D.N. Prescribing of opioid analgesics and related mortality before and after the introduction of long-acting oxycodone. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2009;181(12):891–896. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey M.J., Ghosh R., Chatterjee S., Biswas P., Chatterjee S., Dubey S. COVID-19 and addiction. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome Clinical Research & Reviews. 2020;14(5):817–823. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop A., Lokuge B., Masters D., Sequeira M., Saul P., Dunlop G. Challenges in maintaining treatment services for people who use drugs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Harm Reduction Journal. 2020;17(1):26–27. doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eibl J.K., Wilton A.S., Franklyn A.M., Kurdyak P., Marsh D.C. Vol. 13. 2019. Evaluating the impact of prescribed versus nonprescribed benzodiazepine use in methadone maintenance therapy: Results from a population-based retrospective cohort study; p. 182. (Journal of Addiction Medicine). United States, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA . 2020. The implications of COVID-19 for people who use drugs (PWUD) and drug service providers.https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/topic-overviews/covid-19-and-people-who-use-drugs_en [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA. (n.d.). Take-home naloxone. EMCDDA. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/topic-overviews/take-home-naloxone_en.

- Garcia‐Portilla M.P., Bobes‐Bascaran M.T., Bascaran M.T., Saiz P.A., Bobes J. Long term outcomes of pharmacological treatments for opioid dependence: Does methadone still lead the pack? British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2014;77(2):272–284. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gov.ie. 2020, July. Joint statement from Minister Donnelly, Minister Feighan and Minister O'Brien.https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/b9f00-joint-statement-from-minister-donnelly-minister-feighan-and-minister-obrien/ [Google Scholar]

- Health Research Board. (2017). Drugnet Ireland Newsletter (No. 61). HRB. https://www.hrb.ie/publications/publication/drugnet-ireland-61/returnPage/1/.

- Health Service Executive . 2020. Guidance on contingency planning for people who use drugs and COVID-19.https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/primarycare/socialinclusion/homelessness-and-addiction/clinical-matters/opioid-substitute-treatment/guidance-on-contingency-planning-for-people-who-use-drugs-and-covid-26mar2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Health Service Executive. (n.d.). Clinical guidelines for opiate substitution therapy. HSE. https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/primary/clinical-guidelines-for-opioid-substitution-treatment.pdf.

- Heimer R., McNeil R., Vlahov D. A community responds to the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study in protecting the health and human rights of people who use drugs. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97(4):448–456. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00465-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housing Act, (1988). http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1988/act/28/section/2/enacted/en/html#sec2.

- Kar S.K., Arafat S.M.Y., Sharma P., Dixit A., Marthoenis M., Kabir R. COVID-19 pandemic and addiction: Current problems and future concerns. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;51:102064. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane M., Collins J., Csete J., Duffin T. LSE; London: 2018. Not criminals: Underpinning a health-led approach to drug use.http://www.lse.ac.uk/united-states/Assets/Documents/IDPU-Not-Criminals-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Khatri U.G., Perrone J. Opioid use disorder and COVID-19: Crashing of the crises. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2020;14(4):e6–e7. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lader M., Tylee A., Donoghue J. Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care. CNS drugs. 2009;23(1):19–34. doi: 10.2165/0023210-200923010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larney S., Peacock A., Leung J., Colledge S., Hickman M., Grebely P., Dumchev J., Griffiths K.V., Hines P., Cunningham L., Mattick E.B., Lynskey R.P., Marsden M., Strang J., Vickerman J. Global, regional, and country-level coverage of interventions to prevent and manage HIV and hepatitis C among people who inject drugs: A systematic review. The Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(12):e1208–e1220. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30373-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebrenz M., Boesch L., Stohler R., Caflisch C. Agonist substitution—A treatment alternative for high‐dose benzodiazepine‐dependent patients. Addiction. 2010;105(11):1870–1874. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingford-Hughes A.R., Welch S., Nutt D.J. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance misuse, addiction and comorbidity: Recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2004;18(3):293–335. doi: 10.1177/026988110401800321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Pelayo H., Aubin H.-.J., Drummond C., Dom G., Pascual F., Rehm J. “The post-COVID era”: Challenges in the treatment of substance use disorder (SUD) after the pandemic. BMC Medicine. 2020;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01693-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden J., Darke S., Hall W., Hickman M., Holmes J., Humphreys K. Mitigating and learning from the impact of COVID‐19 infection on addictive disorders. Addiction. 2020;115(6):1007–1010. doi: 10.1111/add.15080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann Pineo M., Schwartz R.M. Commentary on the coronavirus pandemic: Anticipating a fourth wave in the opioid epidemic. Psychological Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S108–S110. doi: 10.1037/tra0000622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosites, E., Parker, E. M., .Clarke, K. E. N., Gaeta, J. M., .Baggett, T. P., Imbert, E., Sankaran, M., Scarborough, A., Huster, K., Hanson, M., Gonzales, E., Rauch, J., Page, L., McMichael, T. M., Keating, R., Marx, G. E., Andrews, T., Schmit, K., Morris, S. B., … et al.Peacock, G. (2020). Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence in homeless shelters—Four U.S. cities, March 27-April 15, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(17), 521–522. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6917e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nielsen S., Dietze P., Lee N., Dunlop A., Taylor D. Concurrent buprenorphine and benzodiazepines use and self‐reported opioid toxicity in opioid substitution treatment. Addiction. 2007;102(4):616–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornell F., Moura H.F., Scherer J.N., Pechansky F., Kessler F.H.P., von Diemen L. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on substance use: Implications for prevention and treatment. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113096. 113096- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer F., Jaffray M., Moffat M.A., Matheson C., McLernon D.J., Coutts A. Prevalence of common chronic respiratory diseases in drug misusers: A cohort study. Primary Care Respiratory Journal. 2012;21(4):377–383. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2012.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr J.M., Kavanagh D.J., Cahill L., Mitchell G., Young R.M. Effectiveness of current treatment approaches for benzodiazepine discontinuation: A meta‐analysis. Addiction. 2009;104(1):13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progression Routes Iniative Community Detoxification Protocols: Benzodiazepines. 2011;102(4):616–622. [Google Scholar]

- Reece A.S. Clinical implications of addiction related immunosuppression. Journal of Infection. 2008;56(6):437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamat S., Hegarty P., Patton R. Same clinic, different conceptions: Drug users’ and healthcare professionals’ perceptions of how stigma may affect clinical care. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2019;49(8):534–545. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, Maryland, United States: 2020. Opioid treatment program (OTP) guidance.www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/otp-guidance-20200316.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M. To substitute or not substitute-optimal tactics for the management of benzodiazepine dependence. Addiction. 2010;105(11):1876–1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjagvad C., Clausen T., Handal M., Skurtveit S. Benzodiazepine prescription for patients in treatment for drug use disorders: A nationwide cohort study in Denmark, 2000-2010. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):168. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0881-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobolowsky, F. A., .Gonzales, E., Self, J. L., .Rao, C. Y., .Keating, R., Marx, G. E., McMichael, T. M., Lukoff, M. D., Duchin, J. S., Huster, K., Rauch, J., McLendon, H., Hanson, M., Nichols, D., Pogosjans, S., Fagalde, M., Lenahan, J., Maier, E., Whitney, H., & … e.t al.Kay, M. (2020). COVID-19 outbreak among three affiliated homeless service sites—King County, Washington, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(17), 523–526. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6917e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tyrer P. Benzodiazepine substitution for dependent patients—Going with the flow. Addiction. 2010;105(11):1875–1876. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . United Nations; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. UNODC/WHO international standards for the treatment of drug use disorders.Https://Www.Unodc.Org/Documents/Drug-Prevention-and-Treatment/UNODC-WHO_International_Standards_Treatment_Drug_Use_Disorders_April_2020.Pdf [Google Scholar]

- Uzun S., Kozumplik O., Jakovljević M., Sedić B. Side effects of treatment with benzodiazepines. Psychiatria Danubina. 2010;105(11):1875–1876. 90- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N.D. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020;173(1):61–62. doi: 10.7326/M20-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weizman T., Gelkopf M., Melamed Y., Adelson M., Bleich A. Treatment of benzodiazepine dependence in methadone maintenance treatment patients: A Comparison of two therapeutic modalities and the role of psychiatric comorbidity. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;37(4):458–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickes W.A., Darke S., Ross J. Clobazam maintenance among methadone maintenance patients with problematic benzodiazepine use: Five case studies. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2000;19(4):401–405. doi: 10.1080/713659419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsten Horsburgh . Scottish Drugs Forum; Frankfurt, Germany: 2018. “My 1st 48 hrs out” - Naloxone-on-Release: Guidelines for naloxone provision upon release from prison and other custodial settings.http://www.sdf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/My-first-48-hours-out-Guidelines-for-naloxone-provision-upon-release-from-prison-and-other-custodial-settings.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . WHO; World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. Naloxone: A take-home antidote to drug overdose that saves lives.https://www.who.int/features/2014/naloxone/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. COVID-19.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/transcripts/who-transcript-emergencies-coronavirus-press-conference-full-13mar2020848c48d2065143bd8d07a1647c863d6b.pdf?sfvrsn=23dd0b04_2 [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Dargan P., Dines A., Yates C., Heyerdahl F., Hovda K. Concurrent use of benzodiazepine by heroin Users—What are the prevalence and the risks associated with this pattern of use? Journal of Medical Toxicology. 2019;15(1):4–11. doi: 10.1007/s13181-018-0674-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]