Abstract

Many human genetic diseases, including Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), are caused by single point mutations. HGPS is a rare disorder that causes premature aging and is usually caused by a de novo point mutation in the LMNA gene. Base editors (BEs) composed of a cytidine deaminase fused to CRISPR/Cas9 nickase are highly efficient at inducing C to T base conversions in a programmable manner and can be used to generate animal disease models with single amino-acid substitutions. Here, we generated the first HGPS monkey model by delivering a BE mRNA and guide RNA (gRNA) targeting the LMNA gene via microinjection into monkey zygotes. Five out of six newborn monkeys carried the mutation specifically at the target site. HGPS monkeys expressed the toxic form of lamin A, progerin, and recapitulated the typical HGPS phenotypes including growth retardation, bone alterations, and vascular abnormalities. Thus, this monkey model genetically and clinically mimics HGPS in humans, demonstrating that the BE system can efficiently and accurately generate patient-specific disease models in non-human primates.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13238-020-00740-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: base editing, non-human primate, HGPS

Introduction

The vast majority of human genetic diseases are caused by single-nucleotide substitutions or point mutations (Landrum et al., 2016). These include the dozens of diseases collectively termed “laminopathies”, which are caused by a variety of mutations in the genes encoding the nuclear lamina proteins (Liu et al., 2011b). A premature aging human disorder, HGPS, is caused by a mutant LMNA gene (Capell and Collins, 2006; Liu et al., 2011a; Kubben et al., 2016). Approximately 90% of HGPS cases are caused by a de novo mutation (1824 C>T, Gly608Gly) in LMNA, which activates a cryptic splice donor site, resulting in an mRNA that lacks 150 nucleotides. The resultant mRNA is subsequently translated into a truncated prelamin A without the ZMPSTE24 cleavage site, generating a toxic protein called “progerin”. The accumulation of progerin leads to pathologies associated with premature aging including growth impairment, dermal and bone abnormalities, lipodystrophy, and progressive atherosclerosis, all of which lead to a shortened lifespan, frequently via myocardial infarction.

Genetically engineered animal models, specifically non-human primates, are a valuable tool used to study human diseases and develop preclinical therapeutic strategies (Chan, 2013). Several recent studies have shown that the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 system could be used to generate gene-knockout or gene-knockin monkeys (Kang et al., 2019). However, due to the low frequency of homologous recombination (HR) in the presence of a donor DNA template, the precise genome editing strategy, especially a single base-pair modification, remains a challenge. Recent improvements in base editing techniques have facilitated the direct and permanent conversion of a base pair in a programmable manner without introducing a double-strand break, which can lead to off-target mutagenesis and/or reduce cell viability due to DNA repair activation (Koblan et al., 2018b; Pickar-Oliver and Gersbach, 2019). Cytidine BEs enable single-nucleotide C- to -T conversions, which can install or correct pathogenic SNPs in much higher editing frequencies in a variety of mammalian cell types (Komor et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Koblan et al., 2018b; Liu et al., 2018a). The recently optimized BE, BE4max, exhibited improvements in gene expression and nuclear localization as well as highly increased editing efficiency (Koblan et al., 2018a). Here, we employed BE4max to explore the possibility of generating a LMNA (1824 C>T, Gly608Gly) mutational Macaca fascicularis (cynomolgus monkey) model for HGPS.

Results

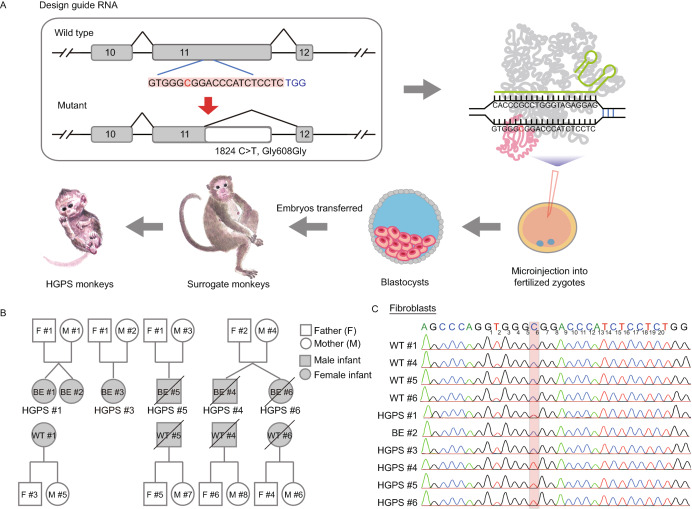

A single guide RNA (sgRNA) was designed to introduce the LMNA (1824 C>T, Gly608Gly) mutation and was co-injected into 86 monkey zygotes along with BE4max mRNA. Then, 41 well-developed embryos injected with sgRNA and BE4max mRNA that displayed normal morphology were transferred into 11 surrogate mothers (Figs. 1A and S1A). Six surrogates were successfully impregnated. Five of the six completed the pregnancy cycle (~150 days) and successfully birthed one infant (referred as to BE #1, 2, 3, 5, and 6, respectively, Fig. 1B) via caesarean delivery. One male infant (BE #4) died before the caesarean operation (~150 days). Two monkeys (BE #5 and BE #6, female and male, respectively) died when they were five months old (Figs. 1B and Fig. S1A; Table S1).

Figure 1.

Generation of HGPS monkeys. (A) The schematic showed the process of generating HGPS monkeys. (B) Family tree of all monkeys used in this study. Black slash indicated that the monkey was dead (HGPS #4 died before the caesarean operation. HGPS #5 and HGPS #6 died when they were five months old.). (C) Sequencing of the sgRNA-targeted regions in the LMNA gene of fibroblasts from WT monkeys and HGPS monkeys. (D) Photographs of WT monkeys and HGPS monkeys when they were 3-months old. Scale bar, 0.83 cm. (E) Heat maps showed on-target editing efficiencies in various tissues of each monkey

PCR and Sanger sequencing were performed to dissect the flanking sequences of the target loci of the sgRNA. Genotyping of fibroblasts and peripheral blood isolated from the genetically engineered monkeys showed that five out of six monkeys (BE #1, BE #3, BE #4, BE #5, and BE #6) carried the expected C to T mutation at position 6, the target locus, and were subsequently renamed HGPS #1, HGPS #3, HGPS #4, HGPS #5, and HGPS #6 (Figs. 1C, 1D, S1C; Table S2). Notably, three (HGPS #4, #5, and #6) out of the six monkeys were homozygous for the expected nonsense mutation at the target site, and the single C-to-T conversion successfully generated cryptic splice sites (Figs. 1C and S1C). HGPS #1 and HGPS #3 were mosaic mutants (Figs. 1C, S1B and S1C).

To further evaluate the on-targeting efficiency of the LMNA locus, we performed whole-genome DNA sequencing (WGS) for six tissues isolated from HGPS and wild type (WT) monkeys, respectively. Chromosomal variation analysis did not reveal any genomic instability (Fig. S2). The editing efficiencies of the 1824 C>T (position 6) conversion were up to 100% in all three homozygous monkeys (HGPS #4, #5, and #6), and did not affect other nucleotides flanking the canonical base editing window (Figs. 1E, S1D, S1E, and Table S2). HGPS #1 harbored an editing frequency of around 50% at the target site (position 6) with two additional endogenous sites containing cytidines at positions 11 and 12 that also harbored the same C>T mutation in a heterozygous manner (Figs. 1E, S1D, S1E, and Table S2). Mutant monkey model (HGPS #3) harbored a mutation frequency of 11%–35% at the LMNA locus (Figs. 1E, S1D, S1E, and Table S2). To evaluate whether base editing in monkey zygotes results in genetic mosaicism after birth, we isolated five additional tissue types from the three homozygous HGPS monkeys (HGPS #4, #5, and #6) immediately after individual death, and subjected them to WGS. All tissues of the three monkeys were 100% edited, and we detected no WT version of LMNA by sequencing (Figs. 1E, S1F–H, and Table S2).

To characterize the potential genome-wide effects of base editing in newborn monkeys, we performed both gRNA-dependent and deaminase-dependent off-target analysis for BE4max. First, the potential genome-wide off-target sites for sgRNA were predicted by Cas-OFFinder (Bae et al., 2014) and analyzed by searching the WGS dataset for promiscuous editing. These sites in HGPS monkeys did not reveal any notable sequence alterations, in comparison to the WT (Table S3). For the deaminase-dependent off-target analysis, WGS analysis was performed in both HGPS and WT monkeys to identify fetus-specific de novo single nucleotide variations (SNVs) and indels. The genome-wide number and proportion of SNVs in both HGPS and WT offspring were extracted by referencing the SNVs of corresponding parents. Comparison of the WT and HGPS monkeys indicated no difference in the number or proportion of de novo SNVs at the genome-wide level (Fig. S3). Given that this comprehensive WGS analysis failed to detect any gRNA-independent random conversions, BE4max appears to be an effective base editor in the cynomolgus monkey. A previous study reported that the cytosine base editor 3 (BE3) induced de novo SNVs in mouse embryos via genome-wide off-target analysis by two-cell embryo Injection (GOTI) (Zuo et al., 2019). However, this method is difficult to perform in non-human primates, especially throughout the embryonic stages. In a recent attempt to study human embryos, the off-target effects of BE3 were analyzed only within the 8-cell stage embryos by GOTI (Zhang et al., 2019a). Therefore, to accurately evaluate both Cas9-dependent and deaminase-dependent off-target mutations by base editing in newborn monkeys, further WGS strategies, which are technically similar to the GOTI method, will be needed.

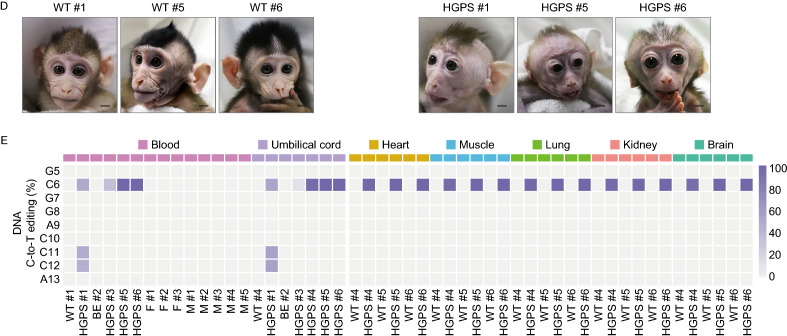

Next, we examined whether BE4max-mediated 1824 C>T editing in LMNA results in the production of progerin in monkeys. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) showed that progerin-specific mRNA was highly expressed in the fibroblasts, skin and the other nine tissues, such as heart and muscle, sampled from homozygous (HGPS #4, #5, and #6) and heterozygous HGPS monkeys (HGPS #1), but not in those from low efficiently edited or non-edited monkeys (HGPS #3 and BE #2), and their age and gender-matched WT counterparts (Figs. 2A, 2B, and S4A). Similar to the qRT-PCR results, Western blot and immunofluorescence analyses both demonstrated the presence of progerin in HGPS fibroblasts and tissues but not in WT tissues (Fig. 2C–H). Progerin was expressed in a tissue-specific manner, with high levels in the skin, heart, and blood vessels, which are known tissues affected by HGPS (Figs. 2D–H and S4B–F) (Aktas et al., 2013; Ullrich and Gordon, 2015). Progerin and Lamin A/C were hardly detected in the brain (Fig. S4D), which is consistent with the neuronal LMNA silencing and absence of cognitive defects in HGPS patients (Jung et al., 2012). Although HGPS #3 exhibited a mutation frequency of roughly 11%–35%, progerin was nearly undetectable in the fibroblasts (Fig. 2A and 2C). These results demonstrate that the engineered heterozygous and homogenous LMNA 1824 C>T monkeys, like HGPS patients, express pathogenic levels of progerin across various tissues. Interestingly, homozygous mice with the Gly609Gly mutation live for roughly 3 months and recapitulate the premature aging of HGPS (Osorio et al., 2011). Homozygous HGPS human stem cells also exhibit the accelerated cellular senescence, compared to their WT counterparts (Wu et al., 2018).

Figure 2.

Expression of progerin in fibroblasts and skin of HGPS monkeys. (A and B) Quantitative analysis of progerin mRNA expression in the fibroblasts (A) and skin (B) of WT and HGPS by qPCR. The data from the HGPS monkeys were normalized to the corresponding data obtained from the WT monkeys. Data shown as mean ± SD, n = 4 wells per condition, ****P < 0.0001 (t-test). (C and D) Western blots showed the expression of progerin in the fibroblasts (C) and skin (D) of HGPS monkeys. For uncropped gels, refer to Source Data. (E–H) Immunofluorescence staining showed the expression of the progerin in the fibroblasts (E), skin (F), heart (G), and aorta (H) of HGPS monkeys. Right panels: the percentages of progerin positive cells. Scale bar, 25 μm, (zoom: 10 μm). Data are mean ± SD. n = 3 monkeys (WT #4, #5, #6 versus HGPS #4, #5, #6) for (E–G) and n = 2 monkeys (WT #5, #6 versus HGPS #5, #6) for (H). ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (t-test for E, F, G and one-way ANOVA for H)

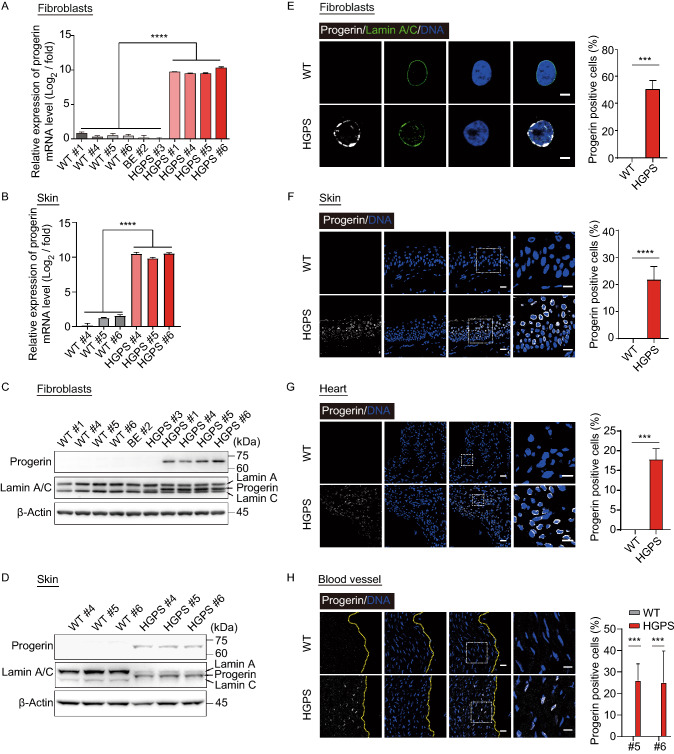

We subsequently investigated whether the characteristic clinical phenotypes of HGPS patients were recapitulated in HGPS monkeys. Highly similar to HGPS human infants (Korf, 2008; Merideth et al., 2008), which appear normal at birth but grow into so-called “wizened dwarves” (Capell and Collins, 2006; Merideth et al., 2008; Ullrich and Gordon, 2015), the three liveborn HGPS monkeys (HGPS #1, #5, #6) had a normal stature at birth, but failed to thrive as WT monkeys (Fig. 3A and 3B). WT monkeys showed an average weight increase of 119 g/month in the first six months of life, whereas HGPS monkeys gained only 15 g/month with a normal head circumference (Figs. 3A, 3B, and S5A). Although HGPS monkeys were born with normal hair covering, excessive hair loss began in the temporal area one month after birth (Fig. 3C). HGPS monkeys also suffered from loss of subcutaneous fat (Fig. 3D). At two months post-birth, all three liveborn HGPS monkeys developed the characteristic craniofacial deformations, including a large bald skull, prominent forehead, protuberant eyes, and a hypoplastic mandible (Fig. 3E and 3F), which mirrors characteristics seen in HGPS patients (Capell and Collins, 2006; Merideth et al., 2008; Ullrich and Gordon, 2015).

Figure 3.

HGPS monkeys exhibited clinical features of HGPS children. (A) Representative photographs showing the appearance of WT monkey (WT #6) and HGPS monkey (HGPS #6) at 87 days of age. The typical phenotypes of growth retardation, bone abnormalities, and hair loss were overserved in HGPS monkeys. Scale bar: left panel, 9 cm; right panels, 4.5 cm. (B) Body weight and length of WT and HGPS monkeys after birth. Data are displayed as mean ± SD, n = 3 (WT #1, #5, #6 versus HGPS #1, #5, #6), nsP > 0.5, *P < 0.5, ****P < 0.0001 (two-way ANOVA). (C) Quantitative analysis of hair loss in WT monkeys and HGPS monkeys at 100 days of age. The percentage of the area with hair was calculated in the top, left, and right side of the monkey head. Data were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 (WT #1, #5, #6 versus HGPS #1, #5, #6), **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA). (D) Body fat percentage of HGPS monkeys and WT monkeys measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Data were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 or 5 (5 WT monkeys versus HGPS #1, #5, #6), *P < 0.5 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). (E) The radiographs of the skull anteroposterior of a WT monkey (WT #6) and a HGPS monkey (HGPS #6). Showing disproportionate large calvarium and contractures finger bone (indicated by yellow arrows) in the HGPS monkey. (F) The smaller mandible (yellow box) and open anterior fontanel (yellow arrow) of the HGPS monkey revealed by skull radiography. Data (right) were presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 (WT #1, #5, #6 versus HGPS #1, #5, #6), **P < 0.01 (t-test). (G) Decreased range of motion in HGPS monkeys determined by the motion tracking. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 (WT #1, #5, #6 versus HGPS #1, #5, #6), *P < 0.05 (t-test). (H) Masson’s trichrome staining of the aorta showing early features of atherosclerosis (c) and vascular fibrosis (d) in HGPS monkeys. Scale bar, 800 μm, 100 μm, 25 μm, 25 μm. n = 2 slices per monkeys (WT #5, #6 versus HGPS #5, #6). Data are mean ± SD, ****P < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA)

HGPS monkeys were unable to extend their fingers (Figs. 3A, 3E, and S5), indicating joint contractures similar to those present in their human counterparts (Ozonoff and Clemett, 1967). Radiographs showed skeletal system aberrations, including overcrowded and small sharpened teeth and a short chin (Fig. 3E and 3F). Although HGPS monkeys began sitting, standing, and walking, bone damage greatly affected their motor abilities, characterized by a notable decrease in distance traveled in the infant incubators (Figs. 3G, S5C and S5D). Serum analysis revealed levels of blood glucose, cholesterol, triglyceride, liver and kidney function (such as alanine aminotransferase [ALT] and aspartate aminotransferase [AST]), and growth hormones, all of which were within the normal range (Fig. S5E and Table S4). All of the HGPS mutant phenotypes appeared to replicate the clinical manifestations of HGPS in humans (Fig. S5F) (Ozonoff and Clemett, 1967; Khalifa, 1989; Monu et al., 1990; Erdem et al., 1994; Stehbens et al., 1999; Gordon et al., 2005; Hennekam, 2006; Merideth et al., 2008; Rastogi and Chander Mohan, 2008; Doubaj et al., 2011; Gordon et al., 2011; Ullrich et al., 2012; Silvera et al., 2013; Chu et al., 2015; Ullrich and Gordon, 2015; Rivera-Torres et al., 2016; Prakash et al., 2018; Xu and Jin, 2019).

HGPS children suffer from global atherosclerosis and vascular complications (Xu and Jin, 2019). To dissect the early onset of disease-associated changes at the tissue level, a histopathological examination was performed on aortic biopsies of the deceased HGPS monkeys at five months old, which is equivalent to the human age of 1.5 years. Identical aortic anatomy was isolated from HGPS monkeys and their age-matched WT counterparts. An increase in vascular wall fibrosis was observed in the HGPS monkeys, which is associated with increased collagen formation and vessel stiffness during normal and pathological aging (Fig. 3H) (Selvin et al., 2010). Besides, the growing endothelium lesion began to encroach on the arterial lumen of HGPS monkeys, which is made evident by the appearance of intimal hyperplasia (Fig. 3H). These histological studies demonstrate that the HGPS monkey model captures the early events of atherosclerosis, which may help identify new biomarkers and preventative interventions to extend the lifespan of HGPS patients, and other individuals susceptible to atherosclerosis.

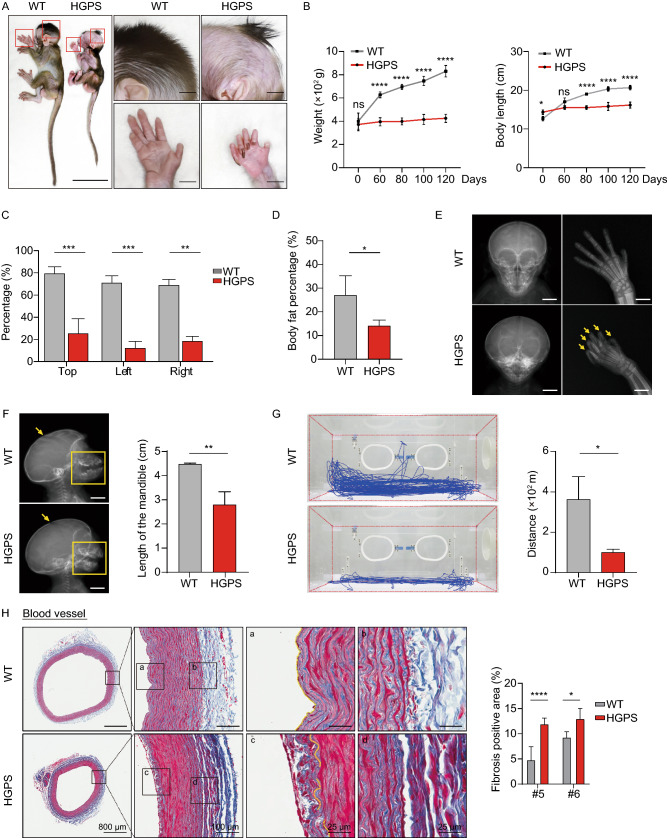

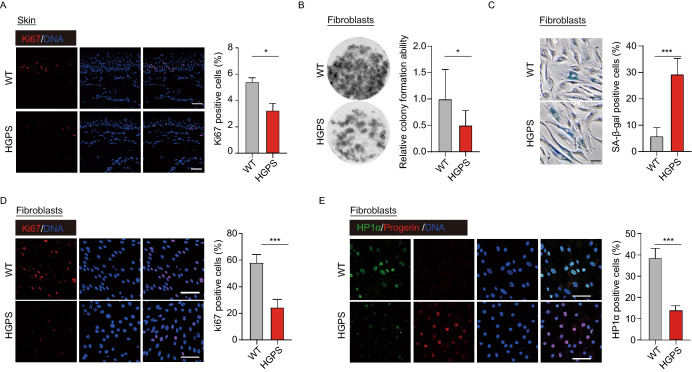

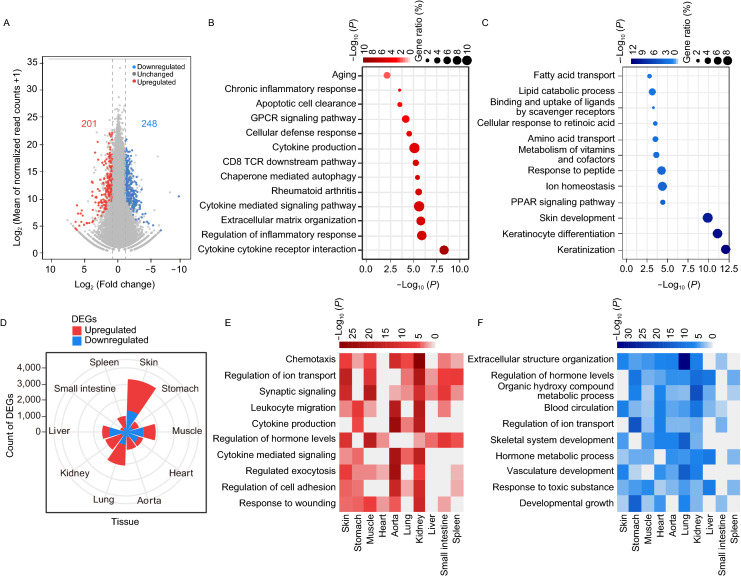

Skin phenotypes are usually apparent as the initial signs of HGPS within the first year of life (Rork et al., 2014). Dermatologic examination showed HGPS monkeys had sclerodermatous skin that is thin and dry with stippled pigmentation and increased vascular markings on the skull and eyelids (Figs. 1D and 3A). A decrease in epidermal proliferation of HGPS skin was also observed (Fig. 4A), which is in agreement with that of aged human skin (Giangreco et al., 2008). Consistently, fibroblasts from HGPS monkeys had a compromised proliferative ability, increased SA-β-gal staining (Senescence Associated β-galactosidase staining), and heterochromatin loss in culture (Fig. 4B–E). To explore the transcriptomic changes during an early stage of HGPS progression, we isolated skin samples from five-month-old HGPS monkeys and their WT counterparts and sequenced the RNA. Comparisons between WT and HGPS monkeys revealed 201 genes that were upregulated and 248 that were downregulated in HGPS skin (Fig. 5A). Subsequent GO analysis showed that the most significant biological pathways enriched by the upregulated genes were “cytokine and cytokine receptor interaction” and “regulation of inflammation response”, while for the downregulated genes, the most significantly enriched pathway was “keratinization” (Fig. 5B and 5C). We also investigated the genome-wide gene expression changes of HGPS monkeys across multiple-tissues, which has not been reported in any HGPS patient (Gordon Leslie et al., 2016; Fleischer et al., 2018). RNA sequencing identified a total of thousands of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in HGPS monkey tissue, compared to age-matched wild type controls, with more DEGs in the skin and lungs (Figs. 5D and SF6; Tables S5 and S6). It was also found that progerin led to an enrichment of “chronic inflammation” across tissues, which is consistent with the GO enrichment analysis of the dataset from the skin samples (Fig. 5E, 5F; Tables S5 and S6). These results highlight systemic inflammation as an early and likely critical response to progerin accumulation during the initial stage of HGPS progression and imply that early anti-inflammatory treatment may help mitigate some of the symptoms in HGPS patients.

Figure 4.

LMNAG608G resulted the decrease of cell proliferation ability. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 demonstrated reduced proliferation of HGPS monkeys’ skin cells. Scale bar, 25 μm. n = 4 (WT #1, #4, #5, #6 versus HGPS #1, #4, #5, #6). Data are mean ± sd., *P < 0.05 (t-test). (B) The clonal images showed reduced expansion ability of the HGPS monkeys’ fibroblasts (n = 4 monkeys WT #1, #4, #5, #6 versus HGPS #1, #4, #5, #6). Data are mean ± SD, *P < 0.05 (t-test). (C) Immunofluorescence staining of SA-β-gal demonstrated increased senescence of HGPS monkeys’ fibroblasts. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 4 (WT #1, #4, #5, #6 versus HGPS #1, #4, #5, #6). Data are mean ± SD, ***P < 0.001 (t-test). (D) Immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 demonstrated a decrease in proliferation of HGPS monkeys’ fibroblasts. Scale bar, 75 μm. n = 4 (WT #1, #4, #5, #6 versus HGPS #1, #4, #5, #6). Data are mean ± SD, ***P < 0.001 (t-test). (E) HP1α’s immunofluorescence staining of fibroblasts demonstrated heterochromatin loss in HGPS monkeys. Scale bar, 75 μm. n = 4 (WT #1, #4, #5, #6 versus HGPS #1, #4, #5, #6). Data are mean ± SD, ***P < 0.001 (t-test)

Figure 5.

Transcriptome features in HGPS monkeys. (A) Scatter plot showed the DEGs between the skin samples of WT (WT#1, WT#5 and WT#6) and HGPS (HGPS #1, HGPS #5 and HGPS #6) monkeys. The number in red showed the count of upregulated DEGs [log2 (Fold change) > 1, adjusted-P < 0.05]; the number in blue shows the count of downregulated DEGs [log2 (Fold change) < −1, adjusted-P < 0.05]. (B and C) Dot plot showed the enriched GO-terms or pathways for upregulated (B) and downregulated (C) genes in skin samples of HGPS (HGPS #1, #5 and #6) compared to WT (WT #1, #5 and #6) monkeys. The color key from white to red (B) and white to blue (C) indicates low to high enrichment level [-log10 (P-value)] for each GO-term or pathway. The circle size indicates to the ratio of genes enriched in the GO-term or pathway. (D) Wind-rose plot showed the numbers of DEGs between WT (WT #5 and WT #6) and HGPS (HGPS #5 and HGPS #6) monkeys in various tissues. Red represents the count of upregulated genes and blue represents the count of downregulated genes between WT monkeys and HGPS monkeys. (E and F) Heat maps showed the enriched GO-terms or pathways for upregulated (E) and downregulated (F) in tissues of the HGPS #5 and HGPS #6 monkeys compared with the matched WT #5 and WT #6 monkeys. The color keys from white to red (E) and white to blue (F) indicate low to high enrichment level [−log10(P-value)] for each GO-term or pathway

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that BE4max enables efficient and precise base editing in the cynomolgus monkey and that the creation of HGPS monkey models can be used for future biomedical research. The HGPS monkeys expressed the mutant progerin protein and exhibited the typical HGPS phenotype. Due to the relatively long reproductive cycle and life span of cynomolgus monkeys, this model may represent a more valuable experimental model than the mouse (Osorio et al., 2011), rabbit (Liu et al., 2018b) or pig (Dorado et al., 2019), in terms of assessing HGPS pathogenesis and the efficacy of related therapeutic intervention.

Material and Methods

Animals

Healthy female cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis), ranging in age from five to eight years with body weights of four to six kg, were selected for use in this study. All animals were housed at the Yunnan Key Laboratory of Primate Biomedical Research (LPBR). All animal procedures were performed following the association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC) for the ethical treatment of primates.

Preparation of mRNA and sgRNA

PCMV_BE4max_P2A_GFP plasmids were obtained from Addgene (#112099). The plasmid was linearized with the restriction enzyme PmeI, and mRNA was synthesized and purified using an In Vitro RNA Transcription Kit (mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra kit, Ambion). SgRNA oligos were amplified and transcribed in vitro using the GeneArt Precision gRNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo) and purified with the MEGAclear Kit (Thermo) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Oocyte collection and in vitro fertilization

Oocyte collection and fertilization were performed as previously described (Niu et al., 2010). In brief, 10 healthy female cynomolgus monkeys aged 5–8 years with regular menstrual cycles were selected as oocyte donors for superovulation, which was performed by intramuscular injection with rhFSH (recombinant human follitropin alpha, GONAL-F, Merck Serono) for 8 days, then rhCG (recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin alpha, OVIDREL, Merck Serono) on day 9 Oocytes were collected by laparoscopic follicular aspiration 32–35 h after rhCG administration. Follicular contents were placed in Hepes-buffered Tyrode’s albumin lactate pyruvate (TALP) medium containing 0.3% BSA at 37 °C. Oocytes were stripped of cumulus cells by pipetting after a brief exposure (<1 min) to hyaluronidase (0.5 mg/mL) in TALP-Hepes to allow visual selection of nuclear maturity metaphase II (MII; first polar body present) oocytes. The maturity oocytes were subjected to intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) immediately and then cultured in CMRL-1066 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Fertilization was confirmed by the presence of the second polar body and two pronuclei.

BE4max injection, embryo culture, and transplantation

Six to eight hours after ICSI, the zygotes were injected with a mixture of BE4max mRNA (100 ng/μL) and sgRNA (50 ng/μL) with total volume 5 pL for each zygote. Microinjections were performed in the cytoplasm of oocytes using a microinjection system under standard conditions. Zygotes were then cultured in the chemically defined hamster embryo culture medium-9 (HECM-9) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, GIBCO) at 37 °C in 5% CaO2 to allow embryo development. The culture medium was replaced every other day until the blastocyst stage. The cleaved embryos with high quality at the two-cell to blastocyst stage were transferred into the oviduct of the matched recipient monkeys. Eleven monkeys were used as surrogate recipients. The earliest pregnancy diagnosis was performed by ultrasonography about 20–30 days after the embryo transfer. Both clinical pregnancy and the number of fetuses were confirmed by fetal cardiac activity and presence of a yolk sac as detected by ultrasonography.

Genomic DNA extraction and sequencing

The genomic DNA from total blood cells and tissues of newborns was extracted by Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega #A1125) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sanger sequencing after PCR was performed with primers as follows: F: 5′-ATGTCTTCCCTCCCCTCCTC-3′; R: 5′-ATCTCTCACACTCCAGCCCT-3′.

Behavioral analysis

Behavioral recording and analysis were performed by three independent trained technicians blinded to the genotypes of the monkeys. The behavior of monkeys in the observation cages was video record without interruption for 30 min between 10:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. each day for five days. The observation cage for video recording was the same as the incubator (40 × 85 × 36 cm, W × L × H) for feeding monkeys. For local motion tracking, the trajectory was extracted from the video recorded by a Kinect 2.0 camera (Microsoft, CA). For action analysis, the actions of monkey movement were analyzed by PrimateScan software Version 1.00 (Clever Sys Inc, VA). The PrimateScan can detect monkey behaviors including arousal, awaken, bounce, circle, climb, come down, crouch, drink, eat, hang, jump, land, move, pace, pause, prostrate, remain, rock, scratch, shake the cage, sitting, sleep, somersault, stand, swing, turn, twitch, and urinate. In this analysis, the actions of sit, pause, and sleep were defined as non-activity behavior, and the others were activity behaviors. The duration of activity and non-activity were statistically compared between wild type and HGPS monkeys.

Hematology

Human growth hormone was detected in machine cobas e-411 (Roche) by hGH Elecsys and cobas -e analyzers kit. The routine blood and biochemical analyses were performed using a BC-2800Vet (Mindray) and VetTest 8008 (BTAP).

Fibroblast isolation and cell culture

The primary fibroblasts of ear skin were obtained according to previously established methods (Zhang et al., 2018). Briefly, the skin samples were sterilized with 75% ethyl alcohol and washed with PBS, then cut into pieces and adhered to the culture dish after removing the hair and fat tissues. The fibroblasts can be outgrown in about one week. All cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose (Hyclone) medium containing 10% FBS (Gibco), 1% glutamax (Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), 2.5 μg/mL plasmocin (Invitrogen) and 1 mol/L tenofovir under 37 °C, 5% CO2 conditions.

Clonal expansion assay

Fibroblasts at 9th passage were seeded in a 12-well plate (Corning) at a density of 3 × 103 cells per well and cultured for approximately 10 days. Then cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min and stained with crystal violet for 15 min. The cellular colonies were photographed and calculated by ImageJ software.

Western blot

Western blot was performed according to previous work (Zhang et al., 2018). For tissue protein analysis, frozen samples were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and lysed with 2× SDS lysis buffer, and for cultured cell protein analysis, cells were harvested and washed with cold PBS and lysed with 2× SDS lysis buffer. Total lysates were quantified using the NANOGROP ONEc (Thermo scientific), approximately 40 μg proteins per lane were separated by SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk and probed with the indicated primary antibodies overnight at 37 °C. Antibodies for Western blot were anti-progerin (sc-81611, 1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-Lamin A/C (sc-7293, 1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-β-actin (sc-69879, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After incubating with the horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies, the signal was detected with an ECL kit (Thermo Fisher). β-actin was used as the loading control.

qPCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and quantified by NANOGROP ONEc (Thermo scientific). 2 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to complementary DNA using the Reverse Transcription Master Mix (Promega). qPCR was carried out with iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The expression level of indicated genes was normalized to GAPDH. The primers used for qPCR: GAPDH-F, 5′- TCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGT-3′; GAPDH-R, 5′-TTGCCATGGGTGGAATCATA-3′; Progerin-F, 5′- ACTGCACCAGCTCGGGG-3′; Progerin-R, 5′-TCTGGGGGCTCTGGGC-3′.

X-ray detection

X-ray autoradiography pictures of whole-body skeletons and bones of interest were taken with a digital camera attached (Ralco, SPAIN) on X-ray film (SEDECAL, SPAIN). Body fat detection was measured using hologic discovery wi (HOLOGIC, USA).

Histology staining

Fresh tissues were fixed with 4% PFA and dehydrated using a gradient alcohol soak, xylene, and then finally embedded in paraffin. Embedded tissues were sliced into sections with a thickness of 5 μm for hematoxylin and eosin staining, according to standard protocols. Fibrosis was examined by Masson staining according to the protocol previously described (Debacq-Chainiaux et al., 2009).

SA-β-Gal staining

The senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay was performed according to a universally accepted method (Ding et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019b).

Immunofluorescence assay

For cell immunofluorescence staining, about 105 cells were seeded into 24-well plates containing coverslips. After one day of adherent culturing, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for ten minutes, then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked with donkey serum for one hour. For the tissue immunofluorescent staining, tissues were sliced and washed with PBS and blocked with donkey serum in PBS for one hour at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells/tissues were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, washed with PBS three times, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488 (goat anti-rabbit) and Alexa Fluor 633 (goat anti-mouse) conjugated secondary antibodies for one hour. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33324 (Invitrogen). TrueVIEW Autofluorescence Quenching Kit (Vector, SP-8400) was applied to slices to reduce tissue autofluorescence. Finally, the coverslips or the tissue slices were mounted with antifade mounting medium (Vectashield) and photographed under a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica SP5).

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics analyses of copy-number variations, repeated sequences, and single nucleotide variants

The genomic DNA from 17 monkeys and five untreated blastocyst embryos were used in the WGS analysis. The 15 monkeys included the newborn monkeys and their parents (HGPS #1, BE #2, HGPS #3, HGPS #4, HGPS #5, HGPS #6, WT #1, F #1, F#2, F #3, M #1, M #2, M#3, M #4, and M #5). Five untreated blastocyst embryos (BC #1, BC #2, BC #3, BC #4, and BC #5) and their corresponding parents (F #C and M #C) were used as a control in the analysis of the genome-wide de novo mutations (DMNs). The genomic DNA of all samples was extracted by Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega #A1125) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. WGS was performed at mean coverages of 30× by Illumina HiSeq X Ten. The raw data were filtered and trimmed using fastp software (v0.20.0) with the base quality value ≥ 25 (-q 25) (Chen et al., 2018). The qualified short reads were mapped to the reference genome (Macaca_fascicularis_5.0.91_release91 from the ensemble) using BWA (v0.7.17) MEM algorithm (Li and Durbin, 2009). After the initial alignment, Samtools (v1.9) was used to filter multiple mapping reads (mapping quality < 30) and sort aligned BAM files (Li et al., 2009). After Q30 filtering, sambamba markdup was run (v0.7) to remove duplicate reads in the mapped BAM files (Tarasov et al., 2015). The uniquely mapped reads were retained for the copy-number variation (CNV), repeat-sequence analysis and the single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) analysis.

In the CNV analysis, chromosomal sequences were placed into bins of 500 kb in length. The normalized coverage depth for each bin was calculated by dividing the raw coverage depth by the average sequencing depth. The repeat regions annotated for Macaca fascicularis by RepeatMasker (db20140131) (http://www.repeatmasker.org) were removed from the genomic sequences before coverage was calculated. The CNV scatterplot was generated using ggplot2.

For the repeat-sequence analysis, Repbase (v.21.11) annotated repeat sequences were used to construct the reference sequence index. Reads were mapped to the indexed repeat sequences, and the mapped reads were grouped into long or short interspersed elements (LINEs or SINEs, respectively), long terminal repeats (LTRs), ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), and other types of repeats. The number of reads mapped to each type of repeat was normalized concerning the total sequencing depth.

The pipeline for variant analysis was shown in the Fig. S2A. The SNVs and Indels were called out from de-duplicated bam files using Strelka (v2.9.0) (Kim et al., 2018). Then the raw variants were filtered using the following thresholds: “QUAL > 30,” “MQ > 30,” “FILTER==‘PASS,’” “GQ > 30,” and “DP > 20.” Heterozygosity distribution of each filtered SNV was shown in Fig. S3C, which was calculated as the depth of the enriched second base divided by the reference base depth. To identify DMNs with higher confidence, we used TrioDeNovo software (v.0.06) (Wei et al., 2015) to remove background variants in the offspring samples with their corresponding parents as control, following the author’s recommended setting and filter. After obtaining the results from running TrioDeNovo (Raw DNMs), only DMNs with the allele balance between 0.3 and 0.7 that were not shared among offspring (Final DMNs) remained. The number of variants and DMNs after each of the filters were shown in the Fig. S2B. Possible off-target sites with up to five mismatched sites were identified using Cas-OFFinder (http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/). 11,483 possible off-target sequences were identified.

RNA sequencing data processing

The processing pipeline for RNA-seq data has been reported previously. Pair-end reads were trimmed using Trim Galore (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore). Cleaned reads were mapped to UCSC Macaca fascicularis (version macFas5) genome using hisat2 (Kim et al., 2015). Trimmed reads with a mapping quality exceeding 20 were counted by HTSeq (version 0.11.0) (Anders et al., 2015). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were revealed using DESeq2 R package (version 1.22.2) using a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P value (adjusted-P value) of less than 0.05 and absolute Log2(fold change) of more than 1 (Love et al., 2014). A subsequent GO enrichment analysis was conducted using Metascape (Zhou et al., 2019).

Data availability

The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (Wang et al., 2017; National Genomics Data Center and Partners, 2020) in BIG Data Center (Nucleic Acids Res 2018), Beijing Institute of Genomics (BIG), Chinese Academy of Sciences, under accession number CRA002684 that are publicly accessible at https://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We are grate to Xinglong Chen, Ziyi Zhao, Baohong Tian and all members from animal facility of the Yunnan Key Laboratory of Primate Biomedical Research for excellent animal welfare and husbandry. We thank Jing He for her technical assistance. The author would like to thank Gabriella Rudy for constructive criticism of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFA0101401), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA16010100), the National Key Research and Development Program (2018YFA0801403, 2018YFC2000100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81921006, 81625009, 91749202, 91949209, 81822018, 91749123, 81671377) and Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS (2016093).

Author contributions

YN., W.J., G.-H.L., and C.L. designed the study and supervised overall experiments. F.W., Y.K., C.S., and C.C. performed gene targeting and generated gene-edited monkeys; W.Z., F.W., Y.F., and L.X. performed the phenotypic analyses; Q.Y. and C.L. designed sgRNA; S.D., Z.L., and H.L. worked on bioinformatics analyses. J.W., Z.L., and L.X. performed behavioral analyses and samples collection; F.W., W.Z., Y.F., Y.K., J.Q., W.J., G.-H.L., and Y.N. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Abbreviations

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BE, base editors; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; CNV, copy-number variation; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; DMNs, de novo mutations; GOTI, genome-wide off-target analysis by two-cell embryo Injection; HGPS, Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome; HR, homologous recombination; LINE-1, long interspersed element type 1; LTRs, long terminal repeat; qRT-PCR, quantitative RT-PCR; WGS, whole-genome DNA sequencing; WT, wild type; SNVs, single nucleotide variations; sgRNA, single guide RNA; SINEs, short interspersed elements.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Fang Wang, Weiqi Zhang, Qiaoyan Yang, Yu Kang, Yanling Fan, Jingkuan Wei, Zunpeng Liu, Shaoxing Dai, Hao Li, Zifan Li, Lizhu Xu, Chu Chu, Jing Qu, Chenyang Si, Weizhi Ji, Guang-hui Liu, Chengzu Long, and Yuyu Niu declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

Footnotes

Fang Wang, Weiqi Zhang, Qiaoyan Yang, Yu Kang and Yanling Fan have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Weizhi Ji, Email: wji@lpbr.cn.

Guang-Hui Liu, Email: ghliu@ioz.ac.cn.

Chengzu Long, Email: Chengzu.long@nyulangone.org.

Yuyu Niu, Email: niuyy@lpbr.cn.

References

- Aktas S, Kiyak M, Ozdil K, Kurtca I, Kibar S, Ahbab S, Karadeniz Y, Saler T. Gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage due to angiodysplasia in hutchinson gilfort Progeria syndrome. J Med Cases. 2013;4(8):576–578. [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S, Park J, Kim JS. Cas-OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1473–1475. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capell BC, Collins FS. Human laminopathies: nuclei gone genetically awry. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:940–952. doi: 10.1038/nrg1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AWS. Progress and prospects for genetic modification of nonhuman primate models in biomedical research. ILAR J. 2013;54:211–223. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilt035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Xu Z-G, Xu Z, Ma L. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome caused by an LMNA mutation: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:271–275. doi: 10.1111/pde.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debacq-Chainiaux F, Erusalimsky JD, Campisi J, Toussaint O. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1798–1806. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Sui L, Ren R, Liu Y, Xu X, Fu L, Bai R, Yuan T, Hao Y, Zhang W, et al. A widely adaptable approach to generate integration-free iPSCs from non-invasively acquired human somatic cells. Protein Cell. 2015;6:386–389. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorado B, Ploen GG, Barettino A, Macias A, Gonzalo P, Andres-Manzano MJ, Gonzalez-Gomez C, Galan-Arriola C, Alfonso JM, Lobo M, et al. Generation and characterization of a novel knockin minipig model of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Cell Discov. 2019;5:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-019-0084-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubaj Y, Lamzouri A, Elalaoui SC, Laarabi FZ, Sefiani A. Syndrome d’Hutchinson-Gilford (progéria). À propos de 3 cas. Archives de Pédiatrie. 2011;18:156–159. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdem N, Güneş AT, Avcı O, Osma E. A case of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome mimicking scleredema in early infancy. Dermatology. 1994;188:318–321. doi: 10.1159/000247175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer JG, Schulte R, Tsai HH, Tyagi S, Ibarra A, Shokhirev MN, Huang L, Hetzer MW, Navlakha S. Predicting age from the transcriptome of human dermal fibroblasts. Genome Biol. 2018;19:221. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1599-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangreco A, Qin M, Pintar JE, Watt FM. Epidermal stem cells are retained in vivo throughout skin aging. Aging Cell. 2008;7:250–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CM, Gordon LB, Snyder BD, Nazarian A, Quinn N, Huh S, Giobbie-Hurder A, Neuberg D, Cleveland R, Kleinman M, et al. Hutchinson–gilford progeria is a skeletal dysplasia. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1670–1679. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon LB, Harten IA, Patti ME, Lichtenstein AH. Reduced adiponectin and HDL cholesterol without elevated C-reactive protein: clues to the biology of premature atherosclerosis in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. J Pediatr. 2005;146:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Leslie B, Kleinman Monica E, Massaro J, D’Agostino Ralph B, Shappell H, Gerhard-Herman M, Smoot Leslie B, Gordon Catherine M, Cleveland Robert H, Nazarian A, et al. Clinical trial of the protein farnesylation inhibitors lonafarnib, pravastatin, and zoledronic acid in children with Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Circulation. 2016;134:114–125. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekam RCM. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: review of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140A:2603–2624. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H-J, Coffinier C, Choe Y, Beigneux AP, Davies BSJ, Yang SH, Barnes RH, Hong J, Sun T, Pleasure SJ, et al. Regulation of prelamin A but not lamin C by miR-9, a brain-specific microRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E423–E431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111780109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Chu C, Wang F, Niu Y. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in nonhuman primates. Dis Models Mech. 2019;12:39982. doi: 10.1242/dmm.039982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa MM. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: report of a Libyan family and evidence of autosomal recessive inheritance. Clin Genet. 1989;35:125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1989.tb02917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Ryu S-M, Kim S-T, Baek G, Kim D, Lim K, Chung E, Kim S, Kim J-S. Highly efficient RNA-guided base editing in mouse embryos. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:435. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Scheffler K, Halpern AL, Bekritsky MA, Noh E, Kallberg M, Chen X, Kim Y, Beyter D, Krusche P, et al. Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nat Methods. 2018;15:591–594. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblan LW, Doman JL, Wilson C, Levy JM, Tay T, Newby GA, Maianti JP, Raguram A, Liu DR. Improving cytidine and adenine base editors by expression optimization and ancestral reconstruction. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:843–846. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblan LW, Doman JL, Wilson C, Levy JM, Tay T, Newby GA, Maianti JP, Raguram A, Liu DR. Improving cytidine and adenine base editors by expression optimization and ancestral reconstruction. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:843–846. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533:420. doi: 10.1038/nature17946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf B. Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome, aging, and the nuclear lamina. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:552–555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0800071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubben N, Zhang W, Wang L, Voss TC, Yang J, Qu J, Liu GH, Misteli T. Repression of the antioxidant NRF2 pathway in premature aging. Cell. 2016;165:1361–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, Brown G, Chao C, Chitipiralla S, Gu B, Hart J, Hoffman D, Hoover J, et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D862–D868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Genome Project Data Processing, S The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, Ding C, Sun H, Xie X, Xu Y, Zhang X, Sun Y, Xiong Y, Ma W, Liu Y, et al. Correction of β-thalassemia mutant by base editor in human embryos. Protein Cell. 2017;8:811–822. doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GH, Barkho BZ, Ruiz S, Diep D, Qu J, Yang SL, Panopoulos AD, Suzuki K, Kurian L, Walsh C, et al. Recapitulation of premature ageing with iPSCs from Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2011;472:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GH, Suzuki K, Qu J, Sancho-Martinez I, Yi F, Li M, Kumar S, Nivet E, Kim J, Soligalla RD, et al. Targeted gene correction of laminopathy-associated LMNA mutations in patient-specific iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Chen M, Chen S, Deng J, Song Y, Lai L, Li Z. Highly efficient RNA-guided base editing in rabbit. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2717. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Chen M, Chen S, Deng J, Song Y, Lai L, Li Z. Highly efficient RNA-guided base editing in rabbit. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2717. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merideth MA, Gordon LB, Clauss S, Sachdev V, Smith ACM, Perry MB, Brewer CC, Zalewski C, Kim HJ, Solomon B, et al. Phenotype and course of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:592–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monu JUV, Benka-Coker LBO, Fatunde Y. Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome in siblings. Skeletal Radiol. 1990;19:585–590. doi: 10.1007/BF00241281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Genomics Data Center, M., and Partners Database Resources of the National Genomics Data Center in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D24–D33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y, Yu Y, Bernat A, Yang S, He X, Guo X, Chen D, Chen Y, Ji S, Si W, et al. Transgenic rhesus monkeys produced by gene transfer into early-cleavage-stage embryos using a simian immunodeficiency virus-based vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17663–17667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006563107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio FG, Navarro CL, Cadinanos J, Lopez-Mejia IC, Quiros PM, Bartoli C, Rivera J, Tazi J, Guzman G, Varela I, et al. Splicing-directed therapy in a new mouse model of human accelerated aging. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:106ra107. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff MB, Clemett AR. Progressive osteolysis in progeria. Am J Roentgenol. 1967;100:75–79. doi: 10.2214/ajr.100.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickar-Oliver A, Gersbach CA. The next generation of CRISPR–Cas technologies and applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:490–507. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0131-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash A, Gordon LB, Kleinman ME, Gurary EB, Massaro J, D’Agostino R, Sr, Kieran MW, Gerhard-Herman M, Smoot L. Cardiac abnormalities in patients with Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:326–334. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi R, Chander Mohan S. Progeria syndrome: a case report. Indian J Orthopaedics. 2008;42:97–99. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.38591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Torres J, Calvo CJ, Llach A, Guzmán-Martínez G, Caballero R, González-Gómez C, Jiménez-Borreguero LJ, Guadix JA, Osorio FG, López-Otín C, et al. Cardiac electrical defects in progeroid mice and Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome patients with nuclear lamina alterations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E7250–E7259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603754113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rork JF, Huang JT, Gordon LB, Kleinman M, Kieran MW, Liang MG. Initial cutaneous manifestations of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:196–202. doi: 10.1111/pde.12284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvin E, Najjar SS, Cornish TC, Halushka MK. A comprehensive histopathological evaluation of vascular medial fibrosis: insights into the pathophysiology of arterial stiffening. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvera VM, Gordon LB, Orbach DB, Campbell SE, Machan JT, Ullrich NJ. Imaging characteristics of cerebrovascular arteriopathy and stroke in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1091–1097. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE, Wakefield SJ, Gilbert-Barness E, Olson RE, Ackerman J. Histological and ultrastructural features of atherosclerosis in progeria. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1999;8:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(98)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov A, Vilella AJ, Cuppen E, Nijman IJ, Prins P. Sambamba: fast processing of NGS alignment formats. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2032–2034. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich NJ, Gordon LB. Chapter 18 – Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. In: Islam MP, Roach ES, editors. Handbook of clinical neurology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 249–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich NJ, Silvera VM, Campbell SE, Gordon LB. Craniofacial abnormalities in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:1512–1518. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Song F, Zhu J, Zhang S, Yang Y, Chen T, Tang B, Dong L, Ding N, Zhang Q, et al. GSA: genome sequence archive. Genomics Proteomics Bioinform. 2017;15:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q, Zhan X, Zhong X, Liu Y, Han Y, Chen W, Li B. A Bayesian framework for de novo mutation calling in parents-offspring trios. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1375–1381. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Zhang W, Song M, Wang W, Wei G, Li W, Lei J, Huang Y, Sang Y, Chan P, et al. Differential stem cell aging kinetics in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome and Werner syndrome. Protein Cell. 2018;9:333–350. doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0517-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Jin Z-G. Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome: cardiovascular pathologies and potential therapies. Trends Biochem Sci. 2019;44:561–564. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Zhou C, Wei Y, Xu C, Pan H, Ying W, Sun Y, Sun Y, Xiao Q, Yao N, et al. Human cleaving embryos enable robust homozygotic nucleotide substitutions by base editors. Genome Biol. 2019;20:101. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1703-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wan H, Feng G, Qu J, Wang J, Jing Y, Ren R, Liu Z, Zhang L, Chen Z, et al. SIRT6 deficiency results in developmental retardation in cynomolgus monkeys. Nature. 2018;560:661–665. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0437-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Liu Z, Liu X, Wang S, Zhang Y, He X, Sun S, Ma S, Shyh-Chang N, Liu F, et al. Telomere-dependent and telomere-independent roles of RAP1 in regulating human stem cell homeostasis. Protein Cell. 2019;10:649–667. doi: 10.1007/s13238-019-0610-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Zhang M, Wei Y, Sun Y, Sun Y, Pan H, Yao N, Zhong W, Li Y, Li W, et al. Highly efficient base editing in human tripronuclear zygotes. Protein Cell. 2017;8:772–775. doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0459-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M, Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, Benner C, Chanda SK. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo E, Sun Y, Wei W, Yuan T, Ying W, Sun H, Yuan L, Steinmetz LM, Li Y, Yang H. Cytosine base editor generates substantial off-target single-nucleotide variants in mouse embryos. Science. 2019;364(6437):289–292. doi: 10.1126/science.aav9973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (Wang et al., 2017; National Genomics Data Center and Partners, 2020) in BIG Data Center (Nucleic Acids Res 2018), Beijing Institute of Genomics (BIG), Chinese Academy of Sciences, under accession number CRA002684 that are publicly accessible at https://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa.