Abstract

End‐stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on dialysis therapy have a higher incidence of renal cell carcinomas (RCCs), which consist of 2 major histopathological types: clear‐cell RCCs (ESRD‐ccRCCs) and acquired cystic disease (ACD)‐associated RCCs. However, their genetic and epigenetic alterations are still poorly understood. Here, we investigated somatic mutations, copy number alterations (CNAs), and DNA methylation profiles in 9 ESRD‐ccRCCs and 7 ACD‐associated RCCs to identify their molecular alterations and cellular origins. Targeted sequencing of 409 cancer‐related genes, including VHL, PBRM1, SETD2, BAP1, KDM5C, MET, KMT2C (MLL3), and TP53, showed ESRD‐ccRCCs harbored frequent VHL mutations, while ACD‐associated RCCs did not. CNA analysis showed that ESRD‐ccRCCs had a frequent loss of chromosome 3p while ACD‐associated RCCs had a gain of chromosome 16. Beadarray methylation analysis showed that ESRD‐ccRCCs had methylation profiles similar to those of sporadic ccRCCs, while ACD‐associated RCCs had profiles similar to those of papillary RCCs. Expression analysis of genes whose expression levels are characteristic to individual segments of a nephron showed that ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs had high expression of proximal tubule cell marker genes, while chromophobe RCCs had high expression of distal tubule cell/collecting duct cell marker genes. In conclusion, ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs had mutation and methylation profiles similar to those of sporadic ccRCCs and papillary RCCs, respectively, and these 2 histopathological types of RCCs were indicated to have originated from proximal tubule cells of the nephron.

Keywords: ACD‐RCC, renal cell carcinoma, epigenetics, hemodialysis, kidney cancer

We revealed that 2 major histopathological types of renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) that arise in end‐stage renal disease (ESRD), namely clear‐cell RCCs (ESRD‐ccRCCs) and acquired cystic disease (ACD)‐associated RCCs, had mutation and methylation profiles similar to those of sporadic ccRCCs and papillary RCCs, respectively. This finding indicates that these 2 histopathological types of RCCs arising in ESRD originated from proximal tubule cells of a nephron.

1. INTRODUCTION

End‐stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on dialysis therapy have a 4‐ to 40‐fold higher incidence of renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) than the general population. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 RCCs arising in ESRD generally consist of 2 major histopathological types: (a) clear‐cell renal cell carcinomas (ESRD‐ccRCCs), and (b) acquired cystic disease (ACD)‐associated RCCs. 5 The involvement of chronic inflammation, induced by uremic toxins and oxidative stress, 6 , 7 and impaired immune surveillance, 8 , 9 has been implicated in the increased incidence. 10 , 11 As advanced RCCs arising in ESRD respond poorly to systemic therapy such as molecular‐targeted therapy, 12 , 13 a greater understanding of their pathophysiology is essential.

In sporadic ccRCCs (ie, developing in the general population), the most common histopathological type of RCCs, genetic and epigenetic alterations have been extensively investigated. 14 , 15 , 16 Dysregulation of VHL is an almost universal finding, and subsequent genomic alterations of PBRM1, SETD2, KDM5C, or BAP1 are involved in the pathogenesis of sporadic ccRCCs. 17 , 18 Furthermore, their cellular origin is thought to be proximal tubule cells of the nephron, based on findings from immunohistochemical staining patterns 19 and mouse ccRCC models. 20 Conversely, alterations in RCCs arising in ESRD, namely ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs, remain largely unexplored. With regards to ACD‐associated RCCs in particular, given that their histopathological diagnosis was only recently added to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2016 classification, 21 , 22 the molecular alterations and cellular origin remain unknown.

We aimed to clarify genetic and epigenetic alterations in the 2 major histopathological types of RCCs arising in ESRD, namely ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs, and to identify their cellular origin.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Renal cell carcinoma and kidney tissue samples

Sixteen RCCs arising in ESRD, including 9 ESRD‐ccRCCs and 7 ACD‐associated RCCs) (Table 1), 33 sporadic RCCs (14 ccRCCs, 8 papillary RCCs [PRCCs], 11 chromophobe RCCs [ChRCCs]), and 7 noncancerous kidney surgical specimens (Table S1) were obtained via radical or partial nephrectomy at Tokyo Women's Medical University and Tokyo Women's Medical University Medical Center East. Each specimen was split into 2 pieces to produce fresh frozen and formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) samples. The fresh frozen samples were used for molecular analyses, and the FFPE samples were used for H&E‐staining to confirm histology and estimate cancer cell fraction by microscopic cell counting. All RCC specimens were confirmed to have cancer cell fractions ≥40%. Histopathological diagnoses were conducted by a certified and experienced pathologist (Y. N.) based on the 2016 WHO classification. 22 In this study, ESRD was defined as a disease which required maintenance hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis therapy, regardless of duration. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tokyo Women's Medical University (approved no. 382) and the National Cancer Center Research Institute (approved no. 2018‐024), and all the specimens were obtained with written informed consents.

TABLE 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics of the 16 RCC surgical specimens arising in ESRD

| Sample ID | Histopathological type | Other tumors in the removed kidney | Sex | Age | pStage | Duration of dialysis therapy | Cause of ESRD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESRD‐ccRCC1 | Clear‐cell RCC | Papillary adenoma | Male | 71 | I | 2 y 10 mo | Unknown |

| ESRD‐ccRCC2 | Clear‐cell RCC | None | Male | 39 | I | 3 mo | Unknown |

| ESRD‐ccRCC3 a | Clear‐cell RCC | None | Male | 39 | I | 2 y 1 mo | IgA nephropathy |

| ESRD‐ccRCC4 | Clear‐cell RCC | Clear‐cell RCC, clear‐cell papillary RCC | Male | 74 | I | 17 y | Nephrosclerosis |

| ESRD‐ccRCC5 a | Clear‐cell RCC | None | Male | 66 | I | 3 y 1 mo | Unknown |

| ESRD‐ccRCC6 | Clear‐cell RCC | None | Male | 62 | I | 11 y | Nephrosclerosis |

| ESRD‐ccRCC7 | Clear‐cell RCC | ACD‐associated RCC | Male | 64 | I | 10 y 5 mo | Diabetic nephropathy |

| ESRD‐ccRCC8 | Clear‐cell RCC | Clear‐cell RCC | Male | 58 | I | 6 mo | Diabetic nephropathy |

| ESRD‐ccRCC9 | Clear‐cell RCC | None | Male | 46 | I | 1 mo | Unknown |

| ACD‐RCC1 | ACD‐associated RCC | None | Male | 50 | I | 18 y | Focal segmental glomerular sclerosis |

| ACD‐RCC2 | ACD‐associated RCC | None | Male | 43 | I | 18 y | IgA nephropathy |

| ACD‐RCC3 | ACD‐associated RCC | None | Male | 42 | I | 18 y | IgA nephropathy |

| ACD‐RCC4 | ACD‐associated RCC | None | Male | 43 | I | 19 y | IgA nephropathy |

| ACD‐RCC5 | ACD‐associated RCC | None | Male | 63 | III | 14 y 9 mo | Diabetic nephropathy |

| ACD‐RCC6 | ACD‐associated RCC | None | Male | 47 | I | 15 y | Diabetic nephropathy |

| ACD‐RCC7 | ACD‐associated RCC | Clear‐cell RCC, oncocytoma | Male | 66 | I | 16 y | Unknown |

Developed from the original non‐functioning kidney in ESRD patients treated with kidney transplantation.

In addition to our own samples, we randomly downloaded the data of 100 sporadic RCC samples (40 ccRCCs, 30 PRCCs, and 30 ChRCCs) and 25 noncancerous kidney tissue samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database; and those of 2 normal kidney tissue samples (GEO accession: GSE79100) from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (Table S2).

2.2. Analysis of somatic mutations and loss of heterozygosity

A multiplex PCR was conducted on genomic DNA for 15 991 amplicons in 409 cancer‐related genes using the Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0 with the Comprehensive Cancer Panel (Life Technologies) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. The 409 cancer‐related genes included VHL, PBRM1, SETD2, BAP1, KDM5C, MET, KMT2C (MLL3), and TP53, which are known to be frequently mutated in sporadic ccRCCs, 15 , 16 PRCCs, 23 and ChRCCs. 24 The synthesized library was loaded onto an Ion PI Chip v3 (Life Technologies) using Ion Chef (Thermo Fischer Scientific), and was sequenced using an Ion Proton sequencer (Life Technologies). The sequences were aligned to the human reference genome hg19 with Torrent Suite 5.0 (Life Technologies). Using CLC Genomics Workbench 8.5 (CLC bio), a variant was considered a somatic mutation in accordance with the following criteria: (a) its frequency in cancer samples was >10%, (b) its frequency in normal samples was <1%, (c) its homopolymer length was <3, (d) it was present in both at least 1 forward and 1 reverse reads, and (e) its coverage was >50. Pathogenicity of mutations was assessed using the COSMIC and ClinVar databases. When information regarding the pathogenicity of a mutation was registered in at least one of them, we considered the mutation as “pathogenic.” When not registered, we described it as “no information.”

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was calculated based upon a previous report showing that the calculation of TMB was accurate when genomic regions ≥1.1 Mb were targeted. 25 The TMB was calculated as the number of synonymous and nonsynonymous somatic mutations, including single nucleotide variant (SNV), multiple nucleotide variant (MNV), and small InDels per megabase.

2.3. DNA methylation analysis

Genome‐wide DNA methylation analysis was conducted using an Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip array (Illumina) covering 865 860 probes (862 927 CpG sites and 2932 non‐CpG sites). The array was scanned with an iScan System (Illumina) and the data were processed using the GenomeStudio Methylation Module Software (Illumina). To adjust for probe design biases, intra‐array normalization by a peak‐based correction method (BMIQ) was performed using a web tool, MACON. 26

To combine the DNA methylation data obtained from 2 different platforms, MethylationEPIC and Methylation450K (TCGA and GEO), we normalized DNA methylation data from the 2 platforms separately using MACON, and selected 439 031 probes common between the 2 platforms and at CpG sites on autosomes. From the 439 031 probes, we first eliminated 36 117 probes that had differences of β values (≥.1) between the 2 platforms in any of the human leukocytes from 2 healthy volunteers and in 293FT cells (data not shown). From the remaining 402 914 probes, we further excluded 84 884 probes whose β values were presented as “NA” in any of the specimens and samples. Finally, 318 030 probes were considered as eligible for genome‐wide DNA methylation analysis. VHL methylation was evaluated at a CpG site located in a CpG island (CGI) in its exon 1 (chr3: 10 183 328 based on hg19) (Table S3). CDKN2A methylation was evaluated at a CpG site located in a CGI in its exon 1 (chr9: 21 974 704) (Table S3). 23 , 24 A β value ≥ .3 was considered to be methylated.

2.4. Analysis of copy number alterations

Copy number alterations (CNAs) were assessed using the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip array with a simplified data‐processing method used in a previous report. 27 In brief, after the exclusion of probes located on sex chromosomes, the remaining probes were combined into a window by joining 1000 adjacent probes, resulting in 844 windows throughout the genome. A ratio of signal intensity in a window to the whole genome was first calculated in a normal sample (leukocytes from a healthy volunteer) (Sn). Next, that in a cancer sample (Sc) was calculated, and the Sc was divided by the Sn (Sc/Sn), reflecting the CNA in the window. This normalization with the intensity in the whole genome was to minimize biases of intensity between normal and cancer samples. Finally, the log2 ratio of the divided signal was calculated, and >0.15 and <−0.15 were defined as chromosomal gain and loss, respectively.

2.5. mRNA expression analysis

Quantitative RT‐PCR (qRT‐PCR) was performed in the CFX connect Real‐Time PCR Detection System (Bio‐Rad Laboratories) using SYBR Green I (BioWhittaker Molecular Applications). A copy number of a gene transcript was normalized to that of GAPDH. The primer sequences for target genes and GAPDH are shown in Table S4.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on FFPE specimens. For antigen retrieval, paraffin sections (3 µm thick) were autoclaved using a microwave for 15 min by adding Tris/EDTA pH 9.0. Anti‐HNF1a (1:3000 dilution; ab242140, Abcam), anti‐HNF4a (1:3000 dilution; ab201460, Abcam), and anti‐CLDN8 (1:2000 dilution, ab183738, Abcam) antibodies were used as the primary antibodies. The staining findings were evaluated by 2 pathologists (ST and YN).

2.7. Gene ontology analysis

Gene ontology (GO) analysis was conducted using a web tool, Gene Ontology enRIchment anaLysis and visuaLizAtion (GOrilla). 28 , 29 Enrichment of GOs in the 3 classes, namely, “Process,” “Function,” and “Component,” was separately analyzed.

2.8. Cluster analysis

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis was performed using R 3.61 with the Heatplus package from Bioconductor. Dimension reduction and visualization was performed by Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) [Leland Mclnnes (2018), URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.03426] using the R with the umap package.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical variables were analyzed using the Mann‐Whitney U test and the Fisher exact test, respectively. The analyses were performed using PASW statistics version 18.0 (SPSS Japan Inc), and a difference with a P‐value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Morphologic features of RCCs arising in ESRD

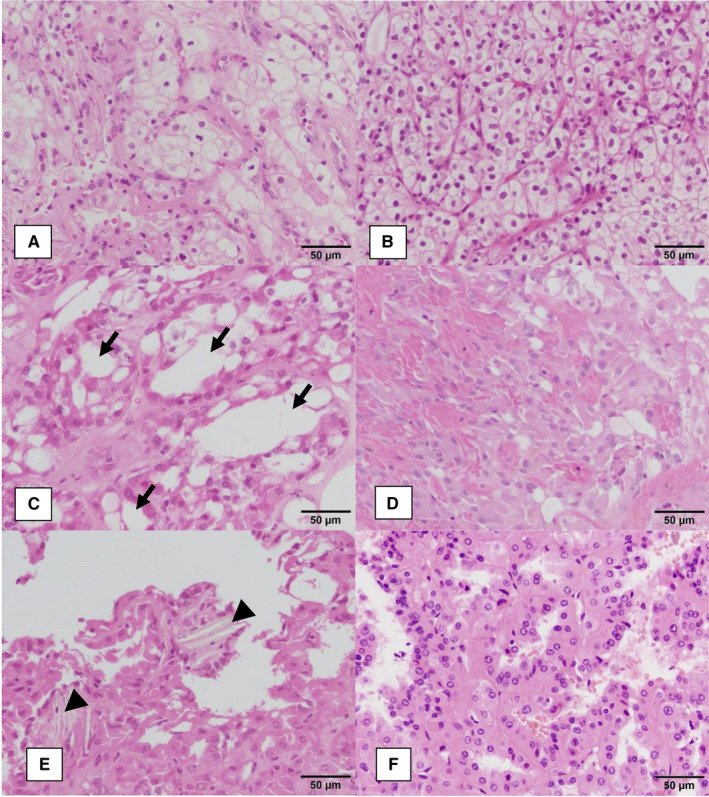

Representative morphologic features of the 2 major histopathological types of RCCs arising in ESRD, namely ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs, are shown in Figure 1. ESRD‐ccRCCs were composed of alveolar architectures of tumor cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure 1A). Also, there were interposing fine sinusoid‐like vascular networks. These histological appearances were similar to those of sporadic ccRCCs (Figure 1B). ACD‐associated RCCs were composed of papillotubular architectures (Figure 1C‐E) and such appearances resembled those in PRCCs (Figure 1F). At the same time, ACD‐associated RCCs had unique features such as frequent microcystic spaces (Figure 1C), intratumoral hemorrhage (Figure 1D), and deposition of calcium oxalate crystals (Figure 1E).

FIGURE 1.

Representative histological findings of RCCs subjected to this study. A, ESRD‐ccRCC (ESRD‐ccRCC9). B, sporadic ccRCC (sporadic ccRCC4). C‐E, ACD‐associated RCCs (C: ACD‐RCC6; D: ACD‐RCC7; E: ACD‐RCC5). F, papillary RCC type II (PRCC6). ESRD‐ccRCCs (A) and sporadic ccRCCs (B) showed similar histological appearance. Both were composed of alveolar architectures of tumor cells with clear cytoplasm. Also, there were interposing fine sinusoid‐like vascular networks. ACD‐associated RCCs (C, D) and PRCCs (F) showed a morphological resemblance, namely papillotubular architectures. At the same time, ACD‐associated RCCs had unique features such as (C) frequent microcystic spaces (arrows), (D) intratumoral hemorrhage, and (E) deposition of calcium oxalate crystals (arrowheads)

3.2. Somatic mutations in RCCs arising in ESRD

In total, 16 RCCs arising in ESRD (9 ESRD‐ccRCCs and 7 ACD‐associated RCCs) were analyzed by targeted sequencing to detect somatic mutations in 409 cancer‐related genes. The 9 ESRD‐ccRCCs harbored 29 somatic mutations with amino acid changes (Table 2). Among these, VHL was most frequently mutated (n = 5), which was in line with previous studies 30 , 31 (Figure S1 and Table S5). To evaluate the association between duration of dialysis therapy and VHL mutation frequency, we divided the ESRD‐ccRCCs based on the duration of dialysis (long: ≥10 y; short: <10 y). However, the VHL mutation frequency was not associated with the duration of dialysis therapy (n = 2/5 [40%] vs n = 3/4 [75%], P = .524).

TABLE 2.

Somatic mutations detected in the 9 ESRD‐ccRCCs

| Sample ID | Gene symbol | Type | Coverage | Variant frequencies (%) | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Pathogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESRD‐ccRCC1 | TCF3 | Insertion | 139 | 79.1 | c.1167+29_1167+30insCA | ||

| PKHD1 | SNV | 212 | 25.9 | c.5743A>C | p.Asn1915His | No information | |

| PER1 | Deletion | 589 | 18.3 | c.2681_2682delGC | p.Gly894fs | Pathogenic | |

| FGFR1 | SNV | 222 | 16.7 | c.1285‐45C>A | |||

| HIF1A | SNV | 495 | 16.2 | c.1362C>A | |||

| DST | Deletion | 558 | 14.7 | c.10312_10314delAAA | p.Lys3438del | Pathogenic | |

| ZNF521 | SNV | 554 | 14.4 | c.1628G>A | p.Arg543Gln | Pathogenic | |

| MLL2 | Deletion | 226 | 13.3 | c.2892_2893delAG | p.Asp966fs | Pathogenic | |

| WRN | Deletion | 371 | 13.2 | c.725‐10_725‐8delTTC | |||

| PKHD1 | Deletion | 464 | 12.7 | c.346_347delGT | p.Val116fs | Pathogenic | |

| GPR124 | Deletion | 341 | 11.1 | c.1139_1140delGC | p.Cys380fs | Pathogenic | |

| CRBN | Deletion | 267 | 10.1 | c.1119_1120delGC | p.Pro374fs | Pathogenic | |

| ESRD‐ccRCC2 | PPARG | MNV | 106 | 27.4 | c.568_569delTGinsAA | p.Cys190Asn | No information |

| PPARG | SNV | 102 | 24.5 | c.571C>A | p.Gln191Lys | No information | |

| VHL | Deletion | 705 | 18.0 | c.399_404delTGAATT | p.Glu134_Leu135del | Pathogenic | |

| ESRD‐ccRCC3 | VHL | SNV | 512 | 31.3 | c.486C>G | p.Cys162Trp | Pathogenic |

| SOX2 | SNV | 609 | 21.2 | c.810C>A | |||

| ESRD‐ccRCC4 | VHL | Deletion | 540 | 41.9 | c.618_619delTG | p.Ala207fs | Pathogenic |

| NFE2L2 | SNV | 563 | 33.0 | c.223C>A | p.Gln75Lys | No information | |

| ESRD‐ccRCC5 | RNF213 | SNV | 366 | 25.7 | c.13545+9T>G | ||

| NOTCH1 | SNV | 561 | 23.9 | c.7564A>G | p.Ser2522Gly | No information | |

| ERBB3 | SNV | 743 | 22.5 | c.2465T>C | p.Met822Thr | No information | |

| PDGFRA | SNV | 452 | 21.7 | c.2562+53C>A | |||

| JAK3 | SNV | 551 | 21.1 | c.2422C>G | p.Leu808Val | No information | |

| IKZF1 | SNV | 793 | 19.5 | c.1544G>A | p.Arg515His | No information | |

| ESRD‐ccRCC6 | WRN | SNV | 413 | 19.1 | c.2184T>A | ||

| SYNE1 | SNV | 1163 | 17.1 | c.3027+43G>A | |||

| TCF12 | SNV | 620 | 16.9 | c.571C>T | p.Pro191Ser | No information | |

| SYK | SNV | 928 | 13.9 | c.1861G>T | p.Ala621Ser | No information | |

| ESRD‐ccRCC7 | VHL | Deletion | 501 | 43.7 | c.494delT | p.Val166fs | Pathogenic |

| ERCC2 | SNV | 324 | 36.1 | c.1666‐16C>T | |||

| MYH11 | SNV | 381 | 35.4 | c.654+7A>G | |||

| JAK1 | SNV | 528 | 30.7 | c.2455G>A | p.Glu819Lys | No information | |

| RAD50 | SNV | 1067 | 26.4 | c.2322C>G | |||

| PKHD1 | SNV | 816 | 25.0 | c.11785+21T>C | |||

| PDE4DIP | SNV | 1878 | 14.2 | c.637‐7226T>A | p.Leu221* | No information | |

| ESRD‐ccRCC8 | KDM5C | SNV | 74 | 66.2 | c.228+1G>A | ||

| TSC2 | SNV | 532 | 37.4 | c.1272G>C | |||

| ESRD‐ccRCC9 | ITGB3 | Deletion | 147 | 23.8 | c.913delA | p.Asn305fs | Pathogenic |

| NOTCH1 | MNV | 1739 | 19.0 | c.6181‐3_6181‐2delCAinsAC | |||

| VHL | SNV | 395 | 16.5 | c.320G>C | p.Arg107Pro | Pathogenic | |

| MLL2 | Deletion | 215 | 14.4 | c.2892_2893delAG | p.Asp966fs | Pathogenic | |

| ADAMTS20 | SNV | 150 | 14.0 | c.670G>T | p.Asp224Tyr | Pathogenic | |

| MLL2 | SNV | 74 | 12.2 | c.14760C>T | |||

| PARP1 | Deletion | 107 | 12.1 | c.2146delG | p.Val716fs | Pathogenic | |

| UBR5 | Deletion | 182 | 10.4 | c.6151delG | p.Ala2051fs | Pathogenic | |

| NF1 | SNV | 97 | 10.3 | c.4044T>C |

* indicates nonsense mutations.

Two specimens (ESRD‐ccRCC1 and ESRD‐ccRCC9) harbored a MLL2 (as also known as KMT2D) mutation, as in sporadic ccRCCs. Conversely, mutations known to be present in sporadic ccRCCs, such as PBRM1, SETD2, or BAP1, were not observed in this study. A mean value of TMB was 3.07/Mb after adding 18 synonymous mutations to the 29 nonsynonymous mutations, and the most frequent base substitutions were C>A and C>T (each, n = 8), followed by C>G and T>C (each, n = 5) (Figure S2A).

The 7 ACD‐associated RCCs harbored 10 somatic mutations with amino acid changes (Table 3), but no mutations were observed in multiple specimens (Table S6). A mean value of TMB was 1.93/Mb after adding 13 synonymous mutations to the 10 nonsynonymous mutations, and the most frequent base substitution was C>T (n = 8), followed by T>C (n = 7) (Figure S2B). One specimen (ACD‐RCC5) harboring a relatively higher TMB (5.88/Mb) was in the advanced disease (Tables 1 and 3).

TABLE 3.

Somatic mutations detected in the 7 ACD‐associated RCCs

| Sample ID | Gene symbol | Type | Coverage | Variant frequencies (%) | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Pathogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACD‐RCC1 | None | ||||||

| ACD‐RCC2 | RRM1 | SNV | 683 | 30.5 | c.1320+48C>T | ||

| LRP1B | SNV | 1139 | 25.6 | c.82+55G>A | |||

| ACD‐RCC3 | SYNE1 | SNV | 635 | 25.7 | c.20112G>T | p.Gln6704His | No information |

| MTOR | Deletion | 266 | 24.4 | c.6000delG | p.Glu2000fs | Pathogenic | |

| ACD‐RCC4 | BRD3 | SNV | 365 | 40.5 | c.381A>G | ||

| ACD‐RCC5 | SF3B1 | SNV | 559 | 36.1 | c.3013+30T>C | ||

| ERBB2 | SNV | 629 | 21.6 | c.2844C>T | |||

| RHOH | SNV | 472 | 21.6 | c.27G>T | p.Leu9Phe | No information | |

| PRKDC | SNV | 559 | 19.9 | c.4216T>C | p.Leu1405Pro, p.*1406Gln | No information | |

| MAGI1 | SNV | 567 | 19.0 | c.*693A>G | |||

| EPHA7 | SNV | 719 | 18.8 | c.1299T>C | |||

| NTRK3 | SNV | 1347 | 17.2 | c.2066C>T | p.Ala689Val | No information | |

| GRM8 | SNV | 645 | 15.8 | c.2678G>A | p.Ser893Asn | No information | |

| RALGDS | SNV | 484 | 14.0 | c.1585C>T | p.Arg474Trp, p.Arg529Trp | No information | |

| FANCA | SNV | 574 | 12.0 | c.187G>A | p.Glu63Lys | No information | |

| ACD‐RCC6 | TCF3 | Insertion | 451 | 73.8 | c.1167+29_1167+30insCA | ||

| FGFR3 | SNV | 507 | 35.9 | c.2169‐18T>C | |||

| NLRP1 | SNV | 53 | 11.3 | c.186G>T | |||

| ACD‐RCC7 | TCF3 | Insertion | 169 | 80.5 | c.1167+29_1167+30insCA | ||

| ARID2 | SNV | 2200 | 38.9 | c.2582T>G | p.Ile861Ser | No information | |

| COL1A1 | SNV | 1150 | 36.6 | c.2288G>A | p.Arg763His | Pathogenic | |

| CSMD3 | SNV | 1906 | 36.4 | c.2409T>C | |||

| ATR | Deletion | 164 | 15.2 | c.3172‐27_3172‐24delATTT |

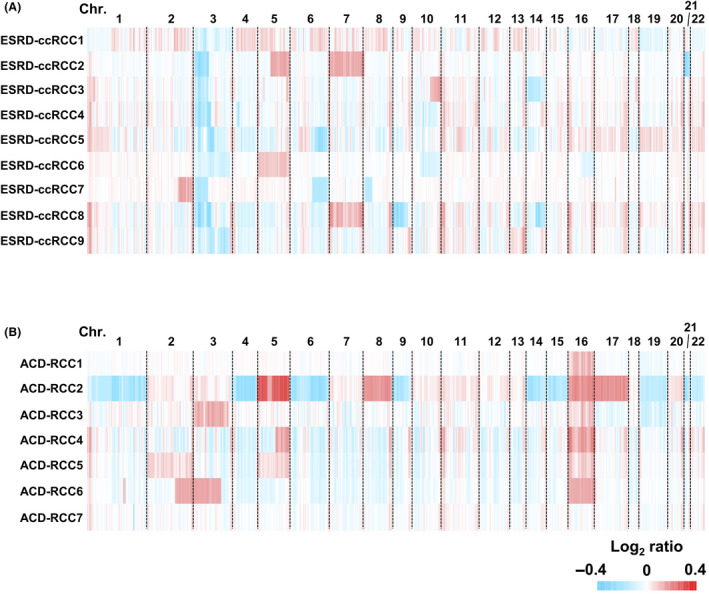

3.3. Copy number alterations in RCCs arising in ESRD

We assessed the genome‐wide CNAs in the 16 RCCs arising in ESRD using an Infinium MethylationEPIC array. In ESRD‐ccRCCs, the most frequent alteration was loss of chromosome 3p between 3p21.1 and 3p.25.3 (7 of 9) (Figure 2A) (windows: 149‐164, Table S7), which was in line with a previous study. 32 The most frequent alteration in ACD‐associated RCCs was the gain of chromosome 16 (5 of 7) (Figure 2B and Table S8), which was in accordance with previous studies. 32 , 33 , 34 One specimen (ACD‐RCC2) exhibited an intensive CNA throughout the genome.

FIGURE 2.

Genome‐wide analysis of copy number alterations in RCCs arising in ESRD. A, Genome‐wide copy number alterations in 9 ESRD‐ccRCCs and (B) 7 ACD‐associated RCCs. The 9 ESRD‐ccRCCs and 7 ACD‐associated RCCs consistently had a loss of chromosome 3p and a gain of chromosome 16, respectively

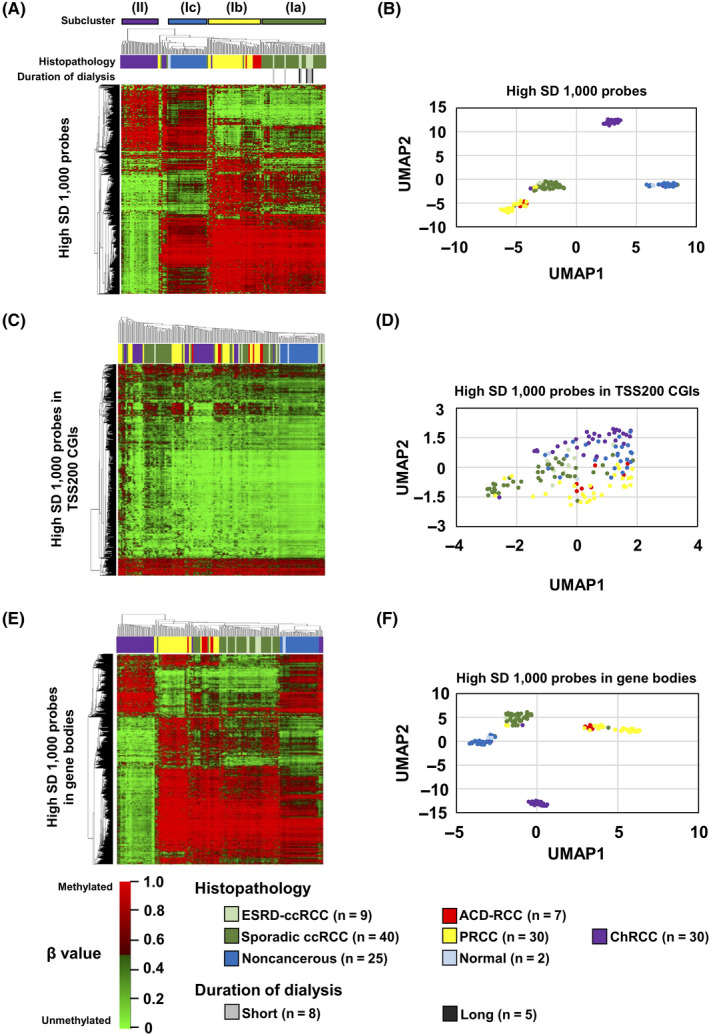

3.4. DNA methylation analysis in RCCs arising in ESRD

We obtained genome‐wide DNA methylation profiles of the 16 RCCs arising in ESRD, and compared them to those of the 100 sporadic RCCs (40 ccRCCs, 30 PRCCs, and 30 ChRCCs), 25 noncancerous and 2 normal kidney tissues obtained from the TCGA and GEO databases. A hierarchical clustering analysis using 1000 probes with the highest standard deviation (SD) among the specimens and samples showed that the DNA methylation profile can clearly classify the specimens and samples, and that the classification was in good agreement with the RCC histopathological types and cancer/normal statuses (Figure 3A). We obtained 2 major clusters (Clusters I and II), of which Cluster I was divided into 3 subclusters (Clusters Ia, Ib, and Ic). Cluster Ia consisted of sporadic and ESRD‐ccRCCs, Cluster Ib of PRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs, Cluster Ic of noncancerous and normal samples, and Cluster II of ChRCCs. ESRD‐ccRCCs with short (or long) duration of dialysis therapy did not cluster together, suggesting no association between DNA methylation profile and duration of dialysis therapy. A UMAP using the 1000 probes also showed that ESRD‐ccRCCs are grouped with sporadic ccRCCs, ACD‐associated RCCs are with PRCCs, and ChRCCs consisted of their own group (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Genome‐wide DNA methylation analysis in RCCs arising in ESRD. A, Hierarchical clustering analysis and (B) UMAP using 1000 probes with the highest SD among all specimens and samples throughout the genome. ESRD‐ccRCCs clustered together with sporadic ccRCCs, and ACD‐RCCs clustered with PRCCs. C, Hierarchical clustering analysis and (D) UMAP using 1000 probes with the highest SD in TSS200 CGIs. These probes failed to classify the histopathological types. E, Hierarchical clustering analysis and (F) UMAP using 1000 probes with the highest SD in gene bodies. ESRD‐ccRCCs clustered together with sporadic ccRCCs, and ACD‐RCCs clustered with PRCCs

To explore which regions in the genome had the strongest influence on this classification of the histopathological types and cancer/normal statuses, we conducted similar analyses using 1000 probes with the highest SD from promoter CGIs (TSS200 CGIs), gene bodies, and enhancers. The probes from TSS200 CGIs and enhancers failed to classify the samples (Figure 3C,D; and Figure S3A,B), but those from gene bodies did so successfully (Figure 3E,F). These findings suggested that the clear distinction among ESRD‐ccRCCs, ACD‐associated RCCs, and ChRCCs reflected mostly their methylome in gene bodies.

Methylation of gene bodies is mostly associated with increased gene expression. 35 , 36 To identify possible pathways regulated by the methylome that define histopathological types of RCCs, GO analysis was conducted using the 1000 probes with the highest SD from gene bodies. GO terms related to “regulations of cellular process” and “development process” were significantly enriched in the class of Process (Table S9), showing that the differentially methylated regions are derived from genes involved in processes of cellular regulation or development.

DNA methylation of 2 genes, VHL and CDKN2A, were especially analyzed in the 16 RCCs arising in ESRD because they are known to be epigenetically silenced in small subsets of sporadic ccRCCs (VHL, 7%‐10%), 15 , 16 , 37 , 38 PRCCs (CDKN2A, 6.2%) 23 and ChRCCs (CDKN2A, 6.1%). 24 However, we did not find either VHL or CDKN2A methylation in ESRD‐ccRCCs or ACD‐associated RCCs (Table S3).

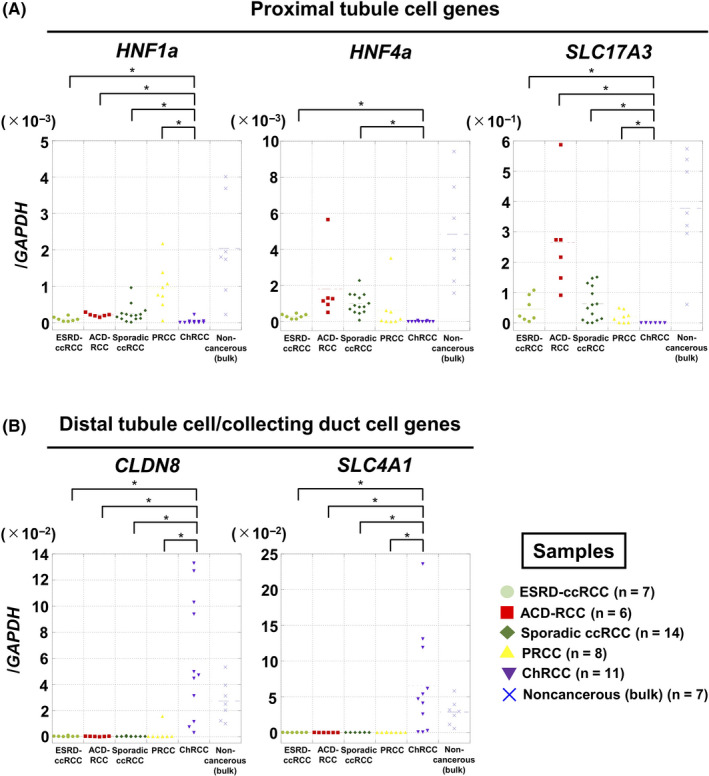

3.5. Cellular origin of RCCs arising in ESRD

Identification of the cellular origin of a cancer is important for understanding pathogenic mechanisms and to establish novel therapeutic approaches. 39 Methylation Cluster I contained sporadic ccRCCs and PRCCs, both of which are considered to develop from proximal tubule cells in a nephron based on immunohistochemical staining patterns, 40 , 41 , 42 and Cluster II contained ChRCCs, which are considered to develop from distal tubule cells/collecting duct cells (Figure 3A). As ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs were included in Clusters Ia and Ib, we hypothesized that these 2 histopathological types of RCCs originated from proximal tubule cells as sporadic ccRCCs and PRCCs.

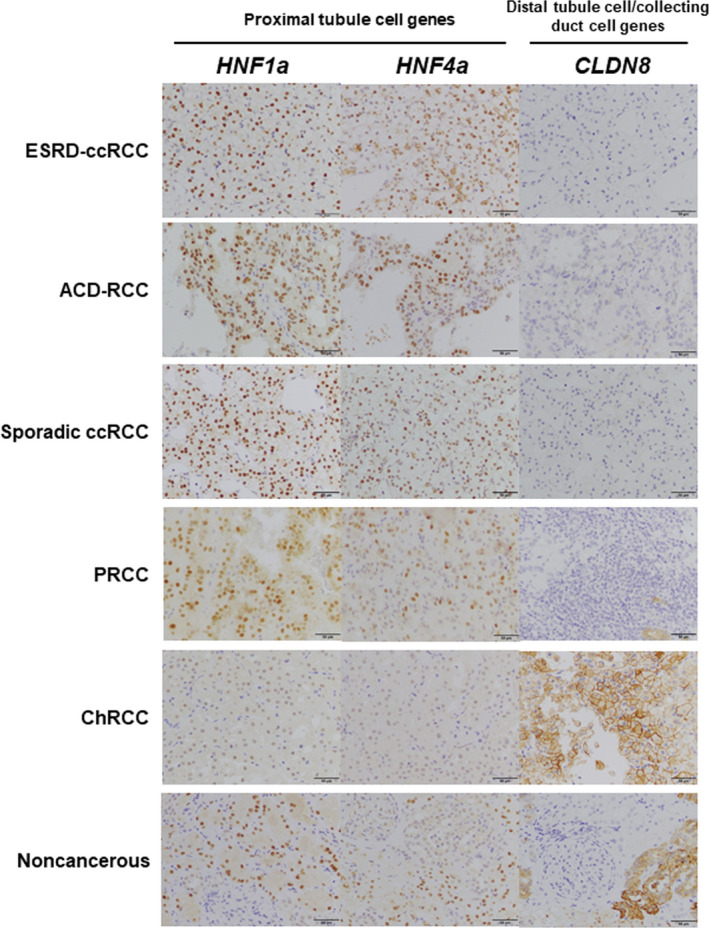

The cellular origins of ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs were further analyzed by measuring expression levels of 5 genes whose expression levels were conserved in individual segments of a normal nephron. 43 , 44 HNF1a, HNF4a, and SLC17A3 are known to be expressed in proximal tubule cells, and CLDN8 and SLC4A1 in distal tubule cells/collecting duct cells. 43 , 44 Due to RNA availability, 7 of the 9 ESRD‐ccRCCs, 6 of the 7 ACD‐associated RCCs, and 33 sporadic RCC (14 ccRCC, 8 PRCC, and 11 ChRCC), and 7 noncancer surgical specimens were analyzed. ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs, along with sporadic ccRCCs and PRCCs, had significantly higher expression levels of HNF1a, HNF4a, and SLC17A3 than ChRCCs (Figure 4A). In contrast, ChRCCs had significantly higher expression levels of CLDN8 and SLC4A1 than ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs, along with sporadic ccRCCs and PRCCs (Figure 4B). Collectively, the expression levels of the marker genes of cellular origin also supported that ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs originated from proximal tubule cells.

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of gene expression of marker genes of cellular origin in RCCs arising in ESRD. A, Expression levels of 3 proximal tubule cell markers (HNF1a, HNF4a, SLC17A3). These were highly expressed in ESRD‐ccRCCs, ACD‐RCCs, sporadic ccRCCs, and PRCCs. B, Expression levels of 2 distal tubule cell/collecting duct cell markers (CLDN8, SLC4A1). These were highly expressed in ChRCCs. *P < .05

3.6. Immunohistochemistry of RCCs arising in ESRD

We examined protein expression of the marker genes of cellular origin in RCCs arising in ESRD by immunohistochemistry to further confirm our findings in genetic, epigenetic, and mRNA analyses. ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs, along with sporadic ccRCCs and PRCCs, had high expression of HNF1a and HNF4a and lacked CLDN8 expression (Figure 5 and Figure S4). In contrast, ChRCCs had high CLDN8 expression and lacked expression of HNF1a and HNF4a. Collectively, the protein expression of marker genes of cellular origin was in line with their mRNA expression levels. These data again supported that ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs originated from proximal tubule cells.

FIGURE 5.

Immunohistochemistry of marker genes of cellular origin in RCCs arising in ESRD. Representative immunohistochemical findings of 2 proximal tubule cell markers (HNF1a, and HNF4a) and one distal tubule cell/collecting duct cell marker (CLDN8). ESRD‐ccRCC (ESRD‐ccRCC7) and ACD‐associated RCC (ACD‐RCC2), along with sporadic ccRCC (sporadic ccRCC5) and PRCC (PRCC8), had high expression of HNF1a and HNF4a and lacked CLDN8 expression. In contrast, ChRCC (ChRCC3) had high CLDN8 expression and lacked expression of HNF1a and HNF4a. Noncancerous, noncancerous6. Scale bars indicates 50 µm

4. DISCUSSION

ESRD‐ccRCCs had mutation and methylation profiles similar to sporadic ccRCCs. The high incidence of VHL mutations in ESRD‐ccRCCs was consistent with previous reports, 30 , 31 and the loss of chromosome 3p was also documented in a previous report. 32 The genome‐wide DNA methylation profile, especially in gene bodies, was shown to be similar between ESRD‐ccRCCs and sporadic ccRCCs. These findings suggested that genetic and epigenetic profiles of ESRD‐ccRCCs resembled those of sporadic ccRCCs, in line with their shared morphologic features (Figure 1). Also, in addition to the DNA methylation analysis, expression analysis of the cellular origin marker genes for the segments of a nephron indicated that ESRD‐ccRCCs were derived from proximal tubule cells.

ACD‐associated RCC was proposed as a unique type of RCC exclusively found in patients with acquired cystic disease on long‐term dialysis, 45 and was established as a new histopathological type based on the WHO 2016 classification. 21 , 22 Morphologically, ACD‐associated RCCs had some similar features to PRCCs 45 , 46 (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry of ACD‐associated RCCs, namely the positive expression of proximal tubule cell markers, such as AMACR, 47 and the absence of staining of distal tubule cell markers, such as Ksp‐cadherin, 42 indicated that they originated from proximal tubule cells. 45 , 46 In this study, the expression of marker genes for cellular origin gave results in line with the previous immunohistochemical findings. ACD‐associated RCCs consistently had a gain of chromosome 16, which is known to be frequently present in PRCCs. 48 , 49 , 50 Importantly, DNA methylation profiles showed that ACD‐associated RCCs are clustered together with PRCCs (Figure 3). Collectively, the pathogenesis of ACD‐associated RCCs may overlap with PRCCs, thereby suggesting that they are likely to have originated from proximal tubule cells.

The effect of DNA methylation or CNAs on pathogenesis in RCCs arising in ESRD remains unknown. DNA methylation would be aberrantly induced by chronic inflammation in ESRD, as reported in other tissues such as colorectal mucosa by ulcerative colitis 51 or gastric mucosa by Helicobacter pylori. 52 Conversely, hyperhomocysteinemia in ESRD is reported to increase S‐adenosylhomocysteine, which leads to demethylation of the genome 53 and subsequently chromosomal instability. 54 , 55 Indeed, one ACD‐associated RCC (ACD‐RCC2) exhibited extensive CNAs (Figure 2B), suggesting a pathogenic role of DNA methylation and CNAs in RCCs arising in ESRD.

This study has several limitations. First, to conclude that proximal tubule cells are the cellular origins, demonstrating that ESRD‐ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs developed from genetically marked proximal tubule cells using genetically engineered mice (eg, Sglt2‐Cre transgenic mice) would be ideal. Nevertheless, the similar profiles of DNA methylation and expression of marker genes of cellular origin strongly implicated that these RCCs originated from proximal tubule cells. Second, we included ESRD‐ccRCCs with only a short duration of dialysis therapy (eg, ESRD‐ccRCC9) because we hypothesized that genetic or epigenetic alteration would be already induced by chronic inflammation in chronic kidney disease. 56 However, it remains to be confirmed that RCCs arising in ESRD with a short duration of dialysis therapy reflected typical RCCs arising in ESRD. Third, we did not find any mutations in PBRM1, SETD2, or BAP1 in ESRD‐ccRCCs, different from sporadic ccRCCs. However, considering the frequency of these mutations (PBRM1: 30%, SETD2: 10%, BAP1: 10%), 15 , 16 the expected numbers of specimens harboring these mutations would be 0‐5 (30% ± 29.9% [95% CI]), 0‐2 (10% ± 29.6%), and 0‐2, respectively. Nevertheless, we could not eliminate the possibility that the prevalence of mutations of these genes is different between sporadic ccRCCs and ESRD‐ccRCCs.

In conclusion, this analysis of genetic and epigenetic alterations of RCCs in ESRD patients showed that ESRD‐ccRCCs have similar molecular profiles to those of sporadic ccRCCs and ACD‐associated RCCs to PRCCs. In addition, DNA methylation and gene expression profiles indicated that these 2 histopathological types of RCCs originated from proximal tubule cells in the nephron.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Fig S1

Fig S2

Fig S3

Fig S4

Tables S1‐S9

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to Drs. Yuki Kobari (Department of Urology, Tokyo Women's Medical University) and Hidekazu Tachibana (Department of Urology, Tokyo Women's Medical University Medical Center East) for collecting the samples, and to Mr. Watanabe Mr. Muneishi, and Ms Tomidokoro (Department of Pathology, Tokyo Women's Medical University) for preparing the FFPE blocks. This research was supported by AMED under Grant Number JP19cm0106451 to Toshikazu Ushijima, JSPS KAKENHI under Grant Number JP18H02704 to Toshikazu Ushijima, and JSPS KAKENHI under Grant Number 17K11162 to Yoji Nagashima.

Ishihara H, Yamashita S, Liu Y‐Y, et al. Genetic and epigenetic profiling indicates the proximal tubule origin of renal cancers in end‐stage renal disease. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:4276–4287. 10.1111/cas.14633

REFERENCES

- 1. Maisonneuve P, Agodoa L, Gellert R, et al. Cancer in patients on dialysis for end‐stage renal disease: an international collaborative study. Lancet. 1999;354:93‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stewart JH, Buccianti G, Agodoa L, et al. Cancers of the kidney and urinary tract in patients on dialysis for end‐stage renal disease: analysis of data from the United States, Europe, and Australia and New Zealand. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:197‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holley JL. Screening, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer in long‐term dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:604‐610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin MY, Kuo MC, Hung CC, et al. Association of dialysis with the risks of cancers. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kondo T, Sasa N, Yamada H, et al. Acquired cystic disease‐associated renal cell carcinoma is the most common subtype in long‐term dialyzed patients: central pathology results according to the 2016 WHO classification in a multi‐institutional study. Pathol Int. 2018;68:543‐549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vanholder R, De Smet R, Glorieux G, et al. Review on uremic toxins: classification, concentration, and interindividual variability. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1934‐1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Libetta C, Sepe V, Esposito P, Galli F, Dal Canton A. Oxidative stress and inflammation: implications in uremia and hemodialysis. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:1189‐1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raska K, Raskova J, Shea SM, et al. T cell subsets and cellular immunity in end‐stage renal disease. Am J Med. 1983;75:734‐740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsakolos ND, Theoharides TC, Hendler ED, et al. Immune defects in chronic renal impairment: evidence for defective regulation of lymphocyte response by macrophages from patients with chronic renal impairment on haemodialysis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;63:218‐227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stopper H, Meysen T, Bockenforde A, Bahner U, Heidland A, Vamvakas S. Increased genomic damage in lymphocytes of patients before and after long‐term maintenance hemodialysis therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34:433‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stopper H, Boullay F, Heidland A, Vienken J, Bahner U. Comet‐assay analysis identifies genomic damage in lymphocytes of uremic patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:296‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Omae K, Kondo T, Kennoki T, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib for treatment of Japanese metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients undergoing hemodialysis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21:126‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ishihara H, Takagi T, Kondo T, Yoshida K, Okumi M, Tanabe K. Efficacy and safety of axitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in patients on hemodialysis for end‐stage renal disease: case series of eight patients. Int J Urol. 2019;26:1081‐1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360‐363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sato Y, Yoshizato T, Shiraishi Y, et al. Integrated molecular analysis of clear‐cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:860‐867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43‐49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hakimi AA, Pham CG, Hsieh JJ. A clear picture of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:849‐850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kapur P, Peña‐Llopis S, Christie A, et al. Effects on survival of BAP1 and PBRM1 mutations in sporadic clear‐cell renal‐cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis with independent validation. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:159‐167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reuter VE, Argani P, Zhou M, Delahunt B. Best practices recommendations in the application of immunohistochemistry in the kidney tumors: report from the International Society of Urologic Pathology consensus conference. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:e35‐e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harlander S, Schönenberger D, Toussaint NC, et al. Combined mutation in Vhl, Trp53 and Rb1 causes clear cell renal cell carcinoma in mice. Nat Med. 2017;23:869‐877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Srigley JR, Delahunt B, Eble JN, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver Classification of Renal Neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1469‐1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs‐part a: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70:93‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Linehan WM, Spellman PT, Ricketts CJ, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of papillary renal‐cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:135‐145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davis C, Ricketts CJ, Wang M, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:319‐330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 2017;9:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iida N, Okuda Y, Ogasawara O, Yamashita S, Takeshima H, Ushijima T. MACON: a web tool for computing DNA methylation data obtained by the Illumina Infinium Human DNA methylation BeadArray. Epigenomics. 2018;10:249‐258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:425‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eden E, Navon R, Steinfeld I, Lipson D, Yakhini Z. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eden E, Lipson D, Yogev S, Yakhini Z. Discovering motifs in ranked lists of DNA sequences. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inoue H, Nonomura N, Kojima Y, et al. Somatic mutations of the von Hippel‐Lindau disease gene in renal carcinomas occurring in patients with long‐term dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2052‐2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yoshida M, Yao M, Ishikawa I, et al. Somatic von Hippel‐Lindau disease gene mutation in clear‐cell renal carcinomas associated with end‐stage renal disease/acquired cystic disease of the kidney. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;35:359‐364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Inoue T, Matsuura K, Yoshimoto T, et al. Genomic profiling of renal cell carcinoma in patients with end‐stage renal disease. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:569‐576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pan CC, Chen YJ, Chang LC, Chang YH, Ho DM. Immunohistochemical and molecular genetic profiling of acquired cystic disease‐associated renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2009;55:145‐153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tajima S, Waki M, Doi W, et al. Acquired cystic disease‐associated renal cell carcinoma with a focal sarcomatoid component: report of a case showing more pronounced polysomy of chromosomes 3 and 16 in the sarcomatoid component. Pathol Int. 2015;65:89‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484‐492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang X, Han H, De Carvalho DD, Lay FD, Jones PA, Liang G. Gene body methylation can alter gene expression and is a therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:577‐590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nickerson ML, Jaeger E, Shi Y, et al. Improved identification of von Hippel‐Lindau gene alterations in clear cell renal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4726‐4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moore LE, Nickerson ML, Brennan P, et al. Von Hippel‐Lindau (VHL) inactivation in sporadic clear cell renal cancer: associations with germline VHL polymorphisms and etiologic risk factors. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Visvader JE. Cells of origin in cancer. Nature. 2011;469:314‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Avery AK, Beckstead J, Renshaw AA, Corless CL. Use of antibodies to RCC and CD10 in the differential diagnosis of renal neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:203‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pan CC, Chen PC, Ho DM. The diagnostic utility of MOC31, BerEP4, RCC marker and CD10 in the classification of renal cell carcinoma and renal oncocytoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 328 cases. Histopathology. 2004;45:452‐459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shen SS, Krishna B, Chirala R, Amato RJ, Truong LD. Kidney‐specific cadherin, a specific marker for the distal portion of the nephron and related renal neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:933‐940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lindgren D, Eriksson P, Krawczyk K, et al. Cell‐type‐specific gene programs of the normal human nephron define kidney cancer subtypes. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1476‐1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Young MD, Mitchell TJ, Vieira Braga FA, et al. Single‐cell transcriptomes from human kidneys reveal the cellular identity of renal tumors. Science. 2018;361:594‐599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tickoo SK, dePeralta‐Venturina MN, Harik LR, et al. Spectrum of epithelial neoplasms in end‐stage renal disease: an experience from 66 tumor‐bearing kidneys with emphasis on histologic patterns distinct from those in sporadic adult renal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:141‐153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Przybycin CG, Harper HL, Reynolds JP, et al. Acquired Cystic Disease‐associated Renal Cell Carcinoma (ACD‐RCC): a multiinstitutional study of 40 cases with clinical follow‐up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(9):1156‐1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tretiakova MS, Sahoo S, Takahashi M, et al. Expression of alpha‐methylacyl‐CoA racemase in papillary renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:69‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Furge KA, Chen J, Koeman J, et al. Detection of DNA copy number changes and oncogenic signaling abnormalities from gene expression data reveals MYC activation in high‐grade papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3171‐3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kovac M, Navas C, Horswell S, et al. Recurrent chromosomal gains and heterogeneous driver mutations characterise papillary renal cancer evolution. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ricketts CJ, De Cubas AA, Fan H, et al. The cancer genome atlas comprehensive molecular characterization of renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2018;23:313‐326.e315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Issa JP, Ahuja N, Toyota M, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA. Accelerated age‐related CpG island methylation in ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3573‐3577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Niwa T, Tsukamoto T, Toyoda T, et al. Inflammatory processes triggered by Helicobacter pylori infection cause aberrant DNA methylation in gastric epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1430‐1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ingrosso D, Cimmino A, Perna AF, et al. Folate treatment and unbalanced methylation and changes of allelic expression induced by hyperhomocysteinaemia in patients with uraemia. Lancet. 2003;361:1693‐1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gaudet F, Hodgson JG, Eden A, et al. Induction of tumors in mice by genomic hypomethylation. Science. 2003;300:489‐492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Eden A, Gaudet F, Waghmare A, Jaenisch R. Chromosomal instability and tumors promoted by DNA hypomethylation. Science. 2003;300:455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rossi M, Campbell K, Johnson D, et al. Uraemic toxins and cardiovascular disease across the chronic kidney disease spectrum: an observational study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:1035‐1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Fig S2

Fig S3

Fig S4

Tables S1‐S9

Supplementary Material