Summary

The importance of innate immunity in cancer is increasingly being recognized with recent reports suggesting tumor cell-intrinsic intracellular functions for innate immunity proteins. However, such functions are often poorly understood, and it is unclear whether these are affected by patient-specific mutations. Here, we show that C4b-binding protein alpha chain (C4BPA), typically thought to reside in the extracellular space, is expressed intracellularly in cancer cells, where it interacts with the NF-κB family member RelA and regulates apoptosis. Interestingly, intracellular C4BPA expression is regulated in a stress- and mutation-dependent manner and C4BPA mutations are associated with improved cancer survival outcome. Using cell lines harboring patient-specific C4BPA mutations, we show that increasing intracellular C4BPA levels correlate with sensitivity to oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, sensitive C4BPA mutants display increased IκBα expression and increased inhibitory IκBα-RelA complex stability. These data suggest a non-canonical intracellular role for C4BPA in regulating NF-κB-dependent apoptosis.

Subject Areas: Genetics, Immunology, Cancer

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

C4BPA mutations are associated with improved overall survival in 23 tumor types

-

•

C4BPA is found, for the first time, to interact with NF-κB family member RelA

-

•

C4BPA expression is regulated in a mutation- and stress-responsive manner

-

•

C4BPA has a non-canonical intracellular function in regulating NF-κB signaling

Genetics; Immunology; Cancer

Introduction

The importance of innate immunity in cancer is increasingly being recognized, with innate immune pathways involved in inflammation, cytosolic nucleic acid sensing, and adaptive immune activation (Hoesel and Schmid, 2013; MacKenzie et al., 2017). NF-κB family members often regulate downstream effector functions (such as inflammation and apoptosis) of innate immunity players (Dunphy et al., 2018; Legrand et al., 2019). NF-κB-dependent transactivation occurs through either the canonical or non-canonical pathways (Karin and Lin, 2002; Hoesel and Schmid, 2013). The canonical NF-κB pathway refers to heterodimers of RelA, c-Rel, and p50, which under unstimulated conditions are retained in the cytoplasm through interaction with inhibitors such as the IκB proteins (IκBα, IκBβ, IκBϵ or p105 and IκBγ) (Karin and Lin, 2002). In response to stimuli such as cytotoxic therapy, activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex (including IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ) leads to IKK-dependent phosphorylation of IκBα, targeting it for proteasomal degradation. IκBα degradation allows translocation of NF-κB dimers (the most abundant being p50-RelA) to the nucleus and activation of NF-κB target genes including anti-apoptotic targets (Barkett and Gilmore, 1999; Chen et al., 2000; Karin and Lin, 2002).

In the non-canonical pathway, activation of NF-κB occurs following binding of ‘non-canonical pathway ligands’ such as CD40L. Ligand binding allows phosphorylation of IKKα by NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK). IKKα phosphorylates precursor protein p100 (IκBδ) triggering ubiquitination and partial proteasomal degradation to p52. p52 can then form a DNA-binding heterodimer with RelB, which translocates to the nucleus to induce a transcriptional program. NF-κB inhibition in cancer cells reduces NF-κB-dependent activation of anti-apoptotic genes and is well known to increase sensitivity of cell lines to cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Barkett and Gilmore, 1999; Chen et al., 2000; Karin and Lin, 2002).

A comprehensive understanding of how cooperation between innate immunity pathways is modulated in response to cytotoxic therapies will yield important insights relevant for our understanding of how to improve cancer therapies. Importantly, we recently reported that somatic mutations in a key innate immunity pathway, the complement system, are widespread across cancer types and correlate with overall survival outcome, suggesting they might modulate responses to standard-of-care agents (Olcina et al., 2018). The complement system is composed of over 40 family members, most of which are thought to be soluble or cell surface proteins having innate immune functions (Sayegh et al., 2014; Ricklin et al., 2016; Reis et al., 2017). As a first line-of-defense system, complement is well poised to exert innate immune effector functions and coordinate with defense pathways in order to mount an appropriate response to invading or foreign species (Ricklin et al., 2016). Although complement is increasingly recognized as a contributor to tumor progression and treatment responses, many aspects of its role in cancer remain to be explored (Reis et al., 2017). The presence of widespread mutations in cancer cells suggests that complement-related genes might exert effects inside tumor cells that may be distinct from their canonical functions. A deeper insight into such intracellular functions, and how they may regulate the interplay with other innate immunity pathways, will be important to further our understanding of tumor progression and treatment response. Here, we show that C4b-binding protein alpha chain (C4BPA), usually uniquely thought to form part of extracellular complement regulator C4b-binding protein (C4BP), is expressed intracellularly in colorectal cancer cells. Furthermore, we report that, intracellularly, C4BPA interacts with NF-κB pathway member RelA and that increased C4BPA levels regulate NF-κB-mediated anti-apoptotic responses following oxaliplatin treatment.

Results

C4BPA Interacts with RelA

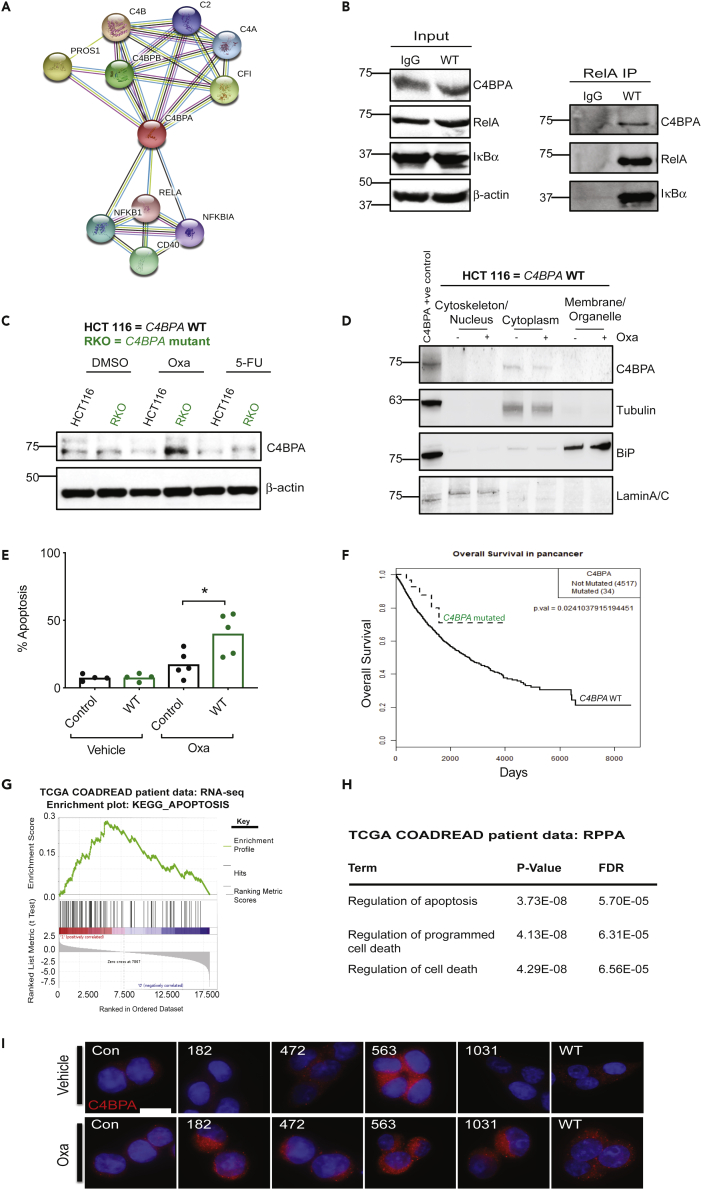

In an attempt to identify previously uncharacterized functions for negative complement regulators, we searched the STRING database for their predicted functional partners (string-db.org). We noted that C4BPA, forming part of complement regulator C4BP, had non-complement associated predicted partners. Specifically, three members of the NF-κB pathway (RelA, NF-κB1 and NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα), were predicted to be present in close interaction nodes with C4BPA (Figure 1A). Intrigued by this prediction, we performed immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments to validate the interaction between C4BPA and NF-κB family members. Since we had previously shown that negative complement regulators are expressed in colorectal cancer cell lines, we chose to perform IP experiments in HCT 116 colorectal cancer cells (Olcina et al., 2018).

Figure 1.

Intracellular C4BPA Interacts with RelA

(A) String.org protein-protein interaction network for C4BPA. Light blue line = known interaction from curated database, pink line = known interaction experimentally tested, dark green line = predicted interaction, gene neighborhood, light green line = text mining interaction source, black line = co-expression interaction source, light purple line = protein homology interaction source.

(B) HCT 116 C4BPAWT cells were transfected with either wild-type (WT) C4BPA or pcDNA3.1. Pull-down with RelA antibody was performed, and input and immunoprecipitation (IP) for the pull-down is shown. Input was collected from the same experiment as the pull-down shown. Western blotting was carried out with the antibodies indicated. n = 2. IgG control is shown in the left lane of the blot.

(C) RKO (colorectal cancer cells with endogenous C4BPA mutation) and HCT 116 (colorectal cancer cells without C4BPA mutation) were treated with DMSO, oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h), or 5-FU (0.1 μg/mL, 24 h). Western blotting was carried out with the antibodies indicated. β-Actin was used as the loading control. n = 3.

(D) Cellular fractionation followed by western blotting was carried out in HCT 116 C4BPAWT treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). Tubulin was used as a control for the cytoplasm fraction, and LaminA/C was used as a nuclear fraction control. Lysate from cells transfected with WT C4BPA was loaded on the right hand side of the gel as a positive control for the detection of intracellular C4BPA, n = 2.

(E) HCT 116 cells where C4BPA had been depleted by CRISPR/Cas9 technology were transfected with a C4BPA WT construct (labeled WT OE). The parental line is also shown for comparison (labeled control). Cells were treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). The graph represents the number of apoptotic/non-apoptotic cells expressed as a % of the whole population. Individual dots represent values for each independent experiment. Statistical significance was evaluated by unpaired t test, ∗ = p < 0.05.

(F) KM curve for overall survival of patients with mutations in C4BPA vs patients without mutation across pan-cancer TCGA data sets (p = 0.0241).

(G) GSEA plot for KEGG pathway ‘Apoptosis’ which appears significantly enriched in patients with mutations in C4BPA compared to no mutation in this gene in COADREAD patients when RNA-seq data are compared. p value = 0.001605, q value = 0.0598. NES = 2.48927.

(H) Table showing top enriched pathways in COADREAD patients with C4BPA mutations (compared to patients without C4BPA mutations) when proteins shown to be differentially expressed in RPPA data are compared and analyzed through DAVID bioinformatics resource.

(I) HCT 116 cells where C4BPA had been depleted by CRISPR-Cas9 technology were transfected with C4BPA-mutant constructs, each representing a mutation found in colorectal cancer TCGA patients or WT C4BPA. The parental line is also shown for comparison (labeled con). Cells were treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h) and stained for C4BPA. Representative images are shown. C4BPA = red. DAPI = blue. Scale bar (shown as white bar) = 10.9 μm.

See also Figure S1.

IP experiments demonstrated that intracellular C4BPA interacts with NF-κB pathway member RelA (Figure 1B). The intracellular nature of this interaction suggests that the biological consequence might be related to stress-responsive rather than immune-dependent functions of RelA. Within the context of cancer treatments, NF-κB-inducing stresses encountered by colorectal cancers include DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agents (Barkett and Gilmore, 1999). We therefore decided to investigate endogenous intracellular C4BPA expression in two commonly used colorectal cancer cell lines (HCT 116 and RKO) treated with two standard-of-care chemotherapy agents: oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (Pires et al., 2010). We found that both HCT 116 and RKO cells expressed endogenous C4BPA. Interestingly, in response to oxaliplatin, C4BPA protein levels were increased only in RKO cells. No major changes in protein expression were observed following 5-FU treatment (Figure 1C). In order to gain a better understanding of C4BPA's intracellular localization, we performed immunofluorescence experiments and found that C4BPA was distributed in the cytoplasm where C4BPA staining was found in the same areas as marked by tubulin (Figure S1A). Furthermore, for the most part, C4BPA did not colocalize with ER chaperone GRP78/BiP, suggesting that perinuclear C4BPA staining does not purely reflect production of the protein in the ER (Figure S1A). By performing subcellular fractionation experiments, we confirmed that intracellular C4BPA expression is primarily cytoplasmic in these cell lines and that oxaliplatin does not affect its subcellular localization (Figure 1D). Together these results indicate that intracellular C4BPA is mostly present in the cytoplasm. These data are consistent with our finding that C4BPA interacts with RelA even under unstressed conditions in which RelA would be mostly expected to be present in the cytoplasm (Karin and Lin, 2002). To our knowledge, this is the first report of intracellular C4BPA expression in cancer cells and of stress-dependent changes in C4BPA expression.

In RKO cells, which displayed oxaliplatin-induced C4BPA expression, we observed a decreased surviving fraction (compared to HCT 116 cells) particularly in response to oxaliplatin (Figure S1B). We also observed increased expression of the DNA Damage Response (DDR) marker, γH2AX and two pro-apoptotic markers, cleaved caspase 3 and Bax, as well as increased % apoptosis in RKO in response to oxaliplatin (Figure S1C and S1D). These data suggest that cells displaying elevated C4BPA expression become more susceptible to oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis. In order to validate this observation, we overexpressed C4BPA in HCT 116 cells. In line with our hypothesis, C4BPA overexpression resulted in increased apoptosis following oxaliplatin treatment (Figures 1E and S1E).

Intrigued by the differences in intracellular C4BPA expression and apoptosis sensitivity found between RKO and HCT 116 cells, we queried the C4BPA mutational status of these cells and noted that RKO colorectal cancer cells have a C4BPA missense mutation (c.1384G > A) while HCT 116 cells harbor wild-type (WT) C4BPA. In order to assess whether genetic alterations of C4BPA occur in patients' tumors, we queried The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data sets and found that C4BPA mutations and copy number alterations were present in a range of cancer types (when pan-cancer studies were queried) (Figure S1F). Interestingly, we found that there was a significant association of C4BPA mutation status and improved outcome when C4BPA mutations again were analyzed at the pan-cancer level (and corrected for type, age, and gender) (Figure 1F). We also noted that colorectal cancer was one example of several positive cancer types in which C4BPA mutations appeared to be associated with improved survival and this association remained even when corrected for age (Figures S1G and S1H and Table S1). In addition, C4BPA expression in tumors appeared significantly higher than in normal colon tissue (Figure S1I). The association with survival benefit in colorectal cancers harboring C4BPA mutations, however, did not correlate with immune response changes such as cytotoxic lymphocyte infiltration or increased cytolytic activity (recently found to be associated with improved survival) (Domingo et al., 2016). We found no significant changes in lymphocyte infiltration or cytolytic activity, suggesting that the association with improved survival is likely independent of these parameters (Figures S1J and S1K).

Consistent with the previously observed changes in apoptosis, when analyzing patient data by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of TCGA RNA-seq data, we found that ‘apoptosis’ was the top differentially expressed pathway in colorectal cancer patients with C4BPA mutations (Figure 1G). Furthermore, analysis of proteins differentially expressed in C4BPA-mutant tumors (from TCGA reverse-phase protein array [RPPA] analysis data) followed by Gene Ontology analysis revealed that versions of ‘regulation of apoptosis/cell death’ also ranked as the top 3 enriched pathways (Figure 1H and Table S2) (Huang et al., 2008, 2009).

Since increased C4BPA expression and C4BPA mutations were both associated with increased apoptosis, we decided to further investigate the effect that patient-specific C4BPA mutations had on C4BPA expression levels. To this end, we transfected C4BPA-mutant expression vectors into HCT 116 cells (with previously depleted endogenous C4BPA). When assessing C4BPA intracellular expression in this system, we noted that C4BPA was localized predominantly in the cytoplasm in C4BPA WT cells (as also shown in Figures 1D and S1A) and that C4BPA mutations did not alter this localization (Figure 1I). Importantly, as was observed in our initial experiments using C4BPA WT (HCT 116) and C4BPA-mutant (RKO) cells (Figure 1C), intracellular C4BPA expression in response to oxaliplatin treatment was only increased in cells harboring C4BPA mutations (Figure 1I).

Patient-Specific C4BPA Mutants Harbor Increased Intracellular C4BPA Expression and Apoptotic Signaling in Response to Oxaliplatin

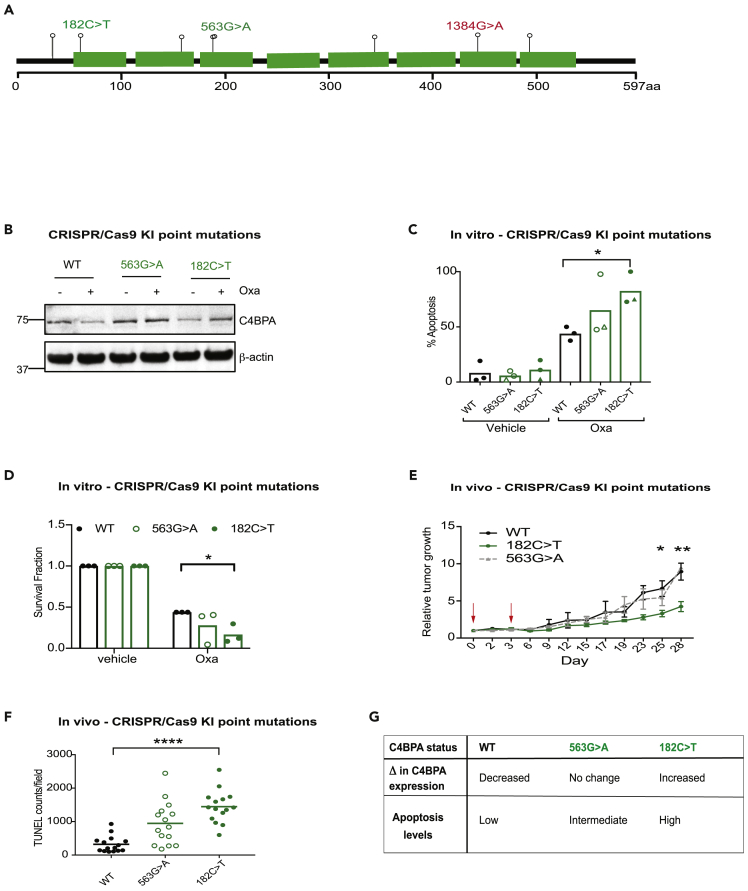

In order to gain deeper insight into whether increased intracellular C4BPA could regulate the observed changes in apoptosis, we decided to generate CRISPR knock-in (KI) mutant cell lines harboring different C4BPA mutations found in tumors from patients with colorectal cancer (Figures 2A and S2A). Generation of these cell lines, we reasoned, would allow us to test, in an endogenous setting: 1) the effects of C4BPA mutations on changes in C4BPA protein expression; and 2) whether increases in intracellular C4BPA levels affect apoptotic signaling. We generated a cell line harboring the 182C > T mutation (cells referred to as HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T) since we previously observed a marked induction of C4BPA protein levels following oxaliplatin treatment in cells overexpressing this mutant (Figure 1I). We also generated a cell line harboring the 563G > A mutation (cells referred to as HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A) since cells overexpressing this mutant showed high baseline C4BPA expression and minimal further increased C4BPA protein expression following oxaliplatin treatment (Figure 1I). HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells, we reasoned, would provide a representative model for increased expression of endogenous intracellular C4BPA, while cell line HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A could serve as a direct control since this mutant does not associate with increased intracellular C4BPA expression upon oxaliplatin treatment. In support of data shown in Figure 1I, both CRISPR KI cell lines showed high levels of C4BPA following oxaliplatin treatment compared to the WT cells, with the greatest increase in C4BPA expression observed in HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells (Figure 2B). As expected, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A cells displayed high levels of C4BPA even under basal conditions, and oxaliplatin treatment caused only minimal further increase (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Patient-Specific C4BPA-Mutants Harbor Increased Intracellular C4BPA Expression and Apoptotic Signaling in Response to Oxaliplatin

(A) Schematic representation of C4BPA mutations identified by TCGA in the COADREAD data set as well as the C4BPA mutation found in RKO colorectal cancer cells (as reported in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer and shown in red text) (cancer.sager.ac.uk). Each lollipop represents a missense mutation. Mutations in green text represent those mutations tested further with the use of CRISPR knock-in cell lines. 182C > T, 563G > A and 1384G > A are highlighted since they are the endogenous mutants experimentally tested in this study. Figure adapted from cbiorportal.org.

(B) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T were treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). Western blotting was carried out with the antibodies indicated. β-Actin was used as the loading control. n = 3.

(C) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T were treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). The graph represents the number of apoptotic/non-apoptotic cells expressed as a % of the whole population. Two different clones are shown for each mutant (represented by different symbols). Individual dots represent values for each independent experiment. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA, ∗ = p < 0.05 between WT Oxa and 182C > T Oxa. n = 3.

(D) Colony survival assay carried out following treatment of HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T with either vehicle of oxaliplatin (80 μM, 1 h). Individual dots represent values for each independent experiment (with three technical replicates per experiment). Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA, ∗ = p < 0.05 between WT Oxa and 182C > T Oxa. n = 3.

(E) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells were injected subcutaneously into athymic nude female mice. Growing tumors were treated with oxaliplatin (10 mg/kg) once tumors reached an average size of 60–90 mm3 (labeled day 0). Treatment was repeated on day 3. Red arrows indicate day of oxaliplatin treatment. n = 7–9 mice per group. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA, ∗ = p < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

(F) Apoptosis was assessed by Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) staining in sections from HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T xenografts treated with oxaliplatin as in (E). Graph represents the number of TUNEL-positive cells per field of view in 2–4 tumors per xenograft model. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA, ∗∗∗∗ = p < 0.0001 between WT and 182C > T.

(G) Table describing the rationale behind the selection of C4BPA mutants generated by CRISPR/Cas9 technology and the summary of C4BPA expression changes (Δ) and apoptosis level observed upon oxaliplatin treatment.

See also Figure S2.

Surprisingly, intracellular protein expression levels did not correlate with changes in mRNA levels in either WT or mutant cell lines (Figure S2B). In addition, C4BPA mRNA expression levels in patients harboring C4BPA mutations were not significantly different from that of patients without mutations (Figure S2C). Together, these data suggest that transcriptional changes alone cannot explain the observed changes in intracellular expression. Increased C4BPA protein expression in cell lysates from C4BPA-mutant cell lines, however, correlated with a decrease in C4BPA secretion into conditioned media following oxaliplatin treatment in two different C4BPA-mutant model systems (Figures S2D and S2E). These data suggest that the observed increased intracellular expression could result from either decreased secretion in the cells harboring sensitive C4BPA mutations or alternatively, an increased uptake of secreted protein. Interestingly, no signs of increased ER stress marker BiP were observed in our mutants compared to C4BPA WT cells (even when treated with tunicamycin and oxaliplatin), suggesting that increased intracellular accumulation of C4BPA does not lead to increased ER stress (Figure S2F).

Next, we used our CRISPR KI cells as tools to understand the effects of oxaliplatin-induced intracellular C4BPA protein expression on apoptosis sensitivity in further detail. When these cell lines were tested in vitro, HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T displayed elevated levels of apoptosis compared to WT control (HCT 116 cells with no C4BPA mutation) or HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A cells (Figure 2C). HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells also displayed the greatest decreased viability in response to oxaliplatin in clonogenic assays (Figures 2D and S2G). These data are in line with our hypothesis that increased C4BPA intracellular expression following oxaliplatin treatment contributes to increased apoptosis and oxaliplatin sensitivity. Furthermore, xenografts from HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells displayed a significant tumor growth delay and increased apoptosis following treatment with oxaliplatin compared to WT control or HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A (Figure 2E, 2F, and S2H). These data support the importance of intracellular C4BPA expression and its correlation with apoptosis sensitivity and improved oxaliplatin tumor response in specific C4BPA-mutant backgrounds. A table describing the rationale behind the selection of C4BPA mutants generated by CRISPR/Cas9 technology and the summary of C4BPA expression and apoptosis level changes observed upon oxaliplatin treatment is shown in Figure 2G.

Patient-Specific C4BPA Mutants Display Decreased NF-κB Signaling

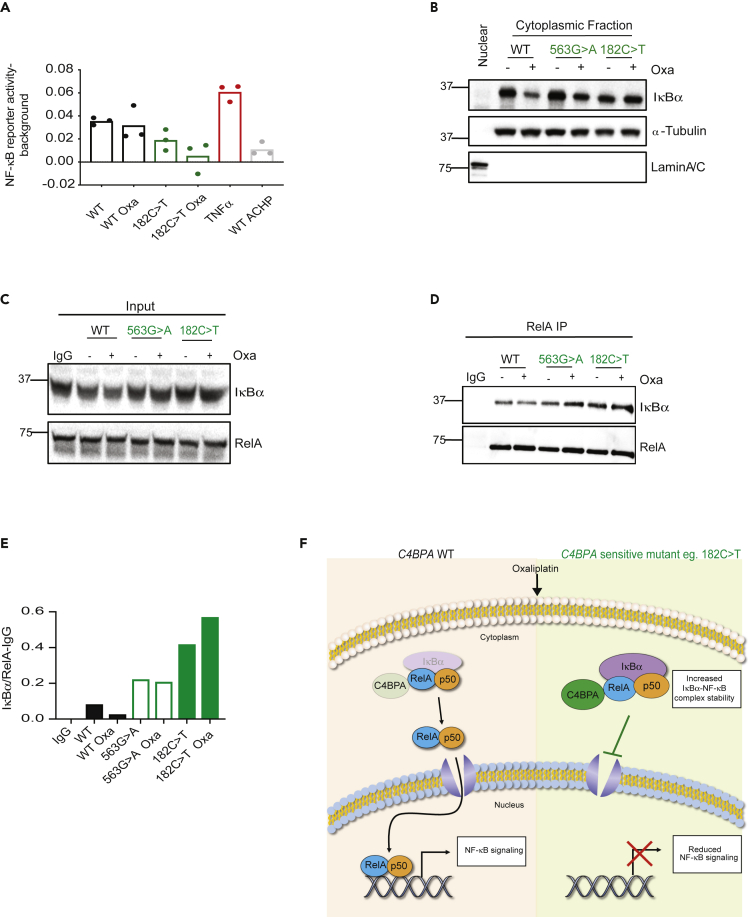

Since NF-κB activation can reduce chemosensitivity by promoting an anti-apoptotic transcriptional response, we hypothesized that an interaction between C4BPA and RelA could regulate oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis by altering NF-κB anti-apoptotic signaling (Barkett and Gilmore, 1999). In support of this hypothesis, cells with the greatest levels of oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis and intracellular C4BPA expression (HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T) displayed reduced NF-κB reporter activity. Remarkably, NF-κB reporter activity in this mutant cell line was reduced to levels comparable to those of WT cells treated with an IκB kinase pharmacological inhibitor (ACHP) (used as a negative control). NF-κB inducer, TNFα, was used as positive control in these experiments (Figure 3A). Decreased NF-κB activity could be a result of aberrant expression or stabilization of NF-κB inhibitor, IκB, upon oxaliplatin treatment. Indeed, while C4BPA WT cells showed a strong reduction in cytoplasmic IκBα levels upon oxaliplatin treatment, this reduction was attenuated in the mutants. HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells that show the greatest apoptosis sensitivity, largest increase in C4BPA expression, and least NF-κB activity showed no decrease in IκBα levels upon treatment (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Patient-Specific C4BPA Mutants Display Decreased NF-κB Signaling

(A) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T were treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h) or vehicle. Treatment of HCT 116 C4BPAWT with TNF-α was used as a positive control. Treatment of HCT 116 C4BPAWT with IκB kinase inhibitor ACHP (25 μM) was used as a negative control. NF-κB reporter assay was carried out. NF-κB reporter luciferase activity – background renilla is shown.

(B) Cellular fractionation to separate nuclear and cytoplasm fractions followed by western blotting was carried out in HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). α-Tubulin was used as a control for the cytoplasmic fraction, and LaminA/C was used as the nuclear control. n = 3. Nuclear fraction is shown in the first lane as control.

(C and D) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells were transfected with either WT C4BPA or mutant C4BPA (563G > A or 182C > T, respectively). Pull-down with RelA antibody was performed, and the input and IP for those experiments is shown. Input was collected from the same experiment as IP. Western blotting was carried out with the antibodies indicated. n = 2. IgG control is shown in the left lane of the blot.

(E) Quantification of IκBα/RelA relative abundance as shown in the western blot in (D).

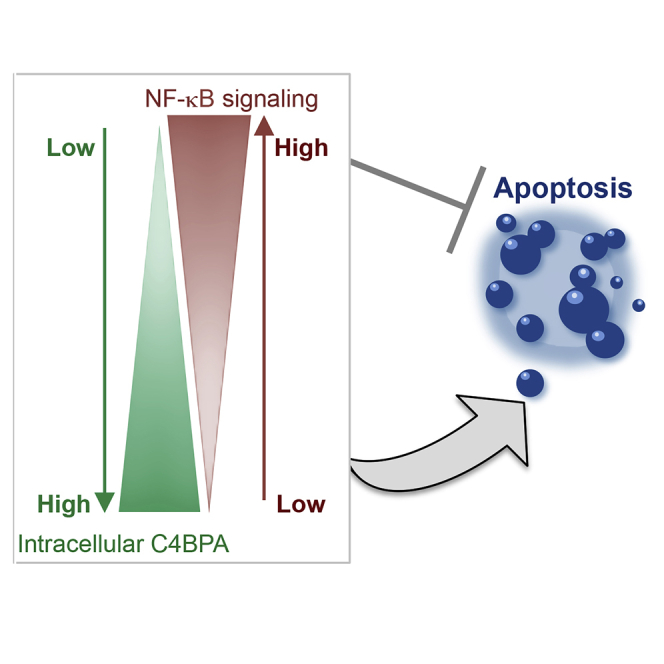

(F) Proposed Model: Cells harboring 'sensitive’ C4BPA mutations (eg C4BPA182C>T) have increased oxaliplatin-induced expression of intracellular C4BPA and cytoplasmic expression of IκBα which are associated with increased retention of IκBα-NF-κB inhibitory complexes and a subsequent attenuated NF-κB signaling. These effects correlate with oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis sensitivity and in vivo oxaliplatin tumor response as shown in Figure 2.

See also Figure S3.

These data suggest that in certain C4BPA-mutant backgrounds (such as the C4BPA182C>T alteration), the activity of DNA-binding NF-κB proteins (such as RelA) is impaired, likely due to the increased expression of the inhibitory NF-κB protein IκBα. Importantly, we observed increased binding of IκBα to RelA following oxaliplatin treatment in C4BPA mutants, with the most significant increase in IκBα-RelA complex stability observed, as expected, in HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells (Figures 3C–3F).

Increased IκBα Expression in C4BPA-Mutant Cell Lines Is Associated with Increased Translation Markers

IκBα undergoes proteasomal degradation following phosphorylation by IKK kinases (Chen et al., 2000; Karin and Lin, 2002). Thus, changes in IκBα stability in C4BPA-mutant cell lines could result from differences in expression of IKK kinases or IκBα phosphorylation. However, we did not observe any decreased expression of the catalytic subunit of the IKK complex, IKKα in C4BPA-mutant cells, which also displayed robust IκBα phosphorylation (Figures S3A and S3B). In addition, while significant increases in mRNA levels of IκBα were observed in HCT 116 C4BPAWT and HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A cell lines, increased IκBα mRNA levels did not reach significance in HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells, indicating that transcriptional changes are also unlikely to be the main contributors to the increased protein IκBα levels observed in these cells (Figures S3C–S3E). Of note, since IκBα itself is thought to be an NF-κB target, the lack of significant increased IκBα expression in HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells is in line with decreased NF-κB activity in this cell line as shown in Figure 3A (Sun et al., 1993). Inhibition of protein synthesis has also been shown to activate NF-κB activity by modulating the synthesis of IκB proteins (O'Dea et al., 2007). We assessed levels of protein translation marker, phosphorylated 4E-BP1 (p4E-BP1), in C4BPA WT and C4BPA-mutant cell lines. Cells harboring C4BPA-mutants (as well as WT overexpression) displayed increased levels of translation marker p4E-BP1, particularly under unstimulated conditions (Figures S3F–S3H). Once again, this phenotype appeared particularly marked in cells harboring the most sensitive mutant, C4BPA182C>T. In order to interrogate whether altered protein synthesis was contributing to increased IκBα protein levels, we used translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX). CHX blockade experiments suggest that IκBα levels can be regulated at the translational level in C4BPA-mutant cell lines with CHX treatment reducing IκBα protein expression back to WT levels (Figure S3I).

Altered NF-κB Signaling Regulates Apoptosis in Patient-Specific C4BPA-Mutant Backgrounds

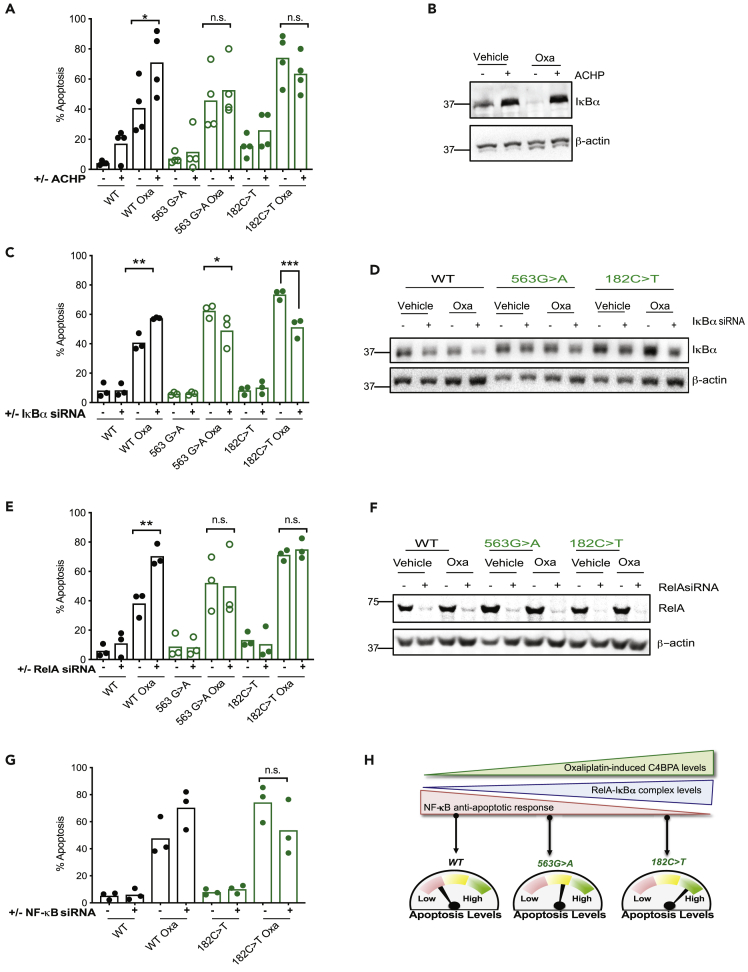

Our data suggest that increased IκBα levels regulate NF-κB signaling in C4BPA mutants through regulation of IκBα-RelA cytoplasmic retention. In order to test whether cytoplasmic retention of NF-κB inhibitory complexes was mediating the increased apoptosis, we used IκB kinase inhibitor, ACHP, which prevents nuclear translocation of NF-κB complexes due to increased IκBα stability (Figures 4A and 4B). We hypothesized that treatment with ACHP should lead to the most pronounced increase in apoptosis levels in WT cells and that no further increase in apoptosis levels would be observed in the most sensitive C4BPA mutants (C4BPA182C>T) owing to the fact that nuclear translocation of NF-κB complexes is likely already impaired in these cells. In support of our hypothesis, treatment with this inhibitor showed that stabilization of IκBα complexes only caused a notable increase of apoptosis in the WT background. These data support our hypothesis that, in C4BPA-mutant backgrounds, the activity of DNA-binding NF-κB proteins is impaired by the increased expression of inhibitory proteins, likely retaining transcriptionally active RelA in inhibitory complexes. As expected, further inhibition of nuclear translocation by ACHP had therefore no additional effect on apoptosis induction in these mutants. To formally test the role of IκBα in apoptotic signaling, we depleted IκBα and assessed apoptosis levels in C4BPA WT or C4BPA-mutant cell lines. We reasoned that depletion of IκBα would relieve some of the inhibition on NF-κB signaling and ‘rescue’ apoptosis levels in C4BPA182C>T-mutant cells to levels comparable to C4BPAWT cells. As expected, reduction of IκBα levels (to protein levels comparable to those found in C4BPAWT) resulted in decreased apoptosis in C4BPA182C>T-mutant cells to levels comparable to C4BPAWT cells treated with Scr siRNA (Figures 4C and 4D). These data suggest that under conditions of increased C4BPA intracellular expression, the activity of DNA-binding NF-κB proteins is particularly impaired due to the increased expression of inhibitory NF-κB proteins.

Figure 4.

Altered NF-κB Signaling Regulates Apoptosis in Patient-Specific C4BPA-Mutant Backgrounds

(A) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells were treated with either DMSO or IκB kinase inhibitor ACHP (25 μM) and oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). The graph represents the number of apoptotic/non-apoptotic cells expressed as a % of the whole population. Individual dots represent mean values for each independent experiment, n = 3–4. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA, ∗∗∗∗ = p < 0.0001. ∗ = p < 0.05.

(B) HCT 116 C4BPAWT cells were treated with either DMSO or ACHP (25 μM) and oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). Western blotting was carried out with the antibodies indicated. β-Actin was used as the loading control. n = 3. ACHP results in stabilization of IκBα as expected.

(C) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells were transfected with either scramble (Scr) or IκBα siRNA and treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). The graph represents the number of apoptotic/non-apoptotic cells expressed as a % of the whole population. Individual dots represent mean values for each independent experiment. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA, ∗ = p < 0.05, ∗∗ = p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ = p < 0.001. n = 3.

(D) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells were transfected with either scramble (Scr) or IκBα siRNA and treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). Western blotting was carried out with the antibodies indicated. β-Actin was used as the loading control. n = 3.

(E) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells were transfected with either Scr or RelA siRNA and treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). The graph represents the number of apoptotic/non-apoptotic cells expressed as a % of the whole population. Individual dots represent mean values for each independent experiment. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA, ∗ = p < 0.05. n = 3.

(F) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells were transfected with either Scr or RelA siRNA and treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). Western blotting was carried out with the antibodies indicated. β-Actin was used as the loading control. n = 3.

(G) HCT 116 C4BPAWT, or HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells were transfected with either Scr or NF-κB1 siRNA and treated with oxaliplatin (40 μM, 24 h). Individual dots represent mean values for each independent experiment. n = 3. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA, ∗∗p < 0.01.

(H) Proposed Model: Increasing stabilization of intracellular C4BPA correlates with increased cytoplasmic IκBα and increased retention of RelA-IκBα in inhibitory complexes. These responses are particularly prominent in C4BPA-mutant cell lines most sensitive to oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis (eg C4BPA182C>T). In contrast, when C4BPA levels are low (such as in a WT setting), decreased cytoplasmic IκBα results in reduced retention of NF-κB in inhibitory complexes following oxaliplatin treatment and reduced apoptosis levels. A mutant with no C4BPA stabilization (C4BPA563G>A) following oxaliplatin treatment shows an intermediate apoptotic response correlating with intermediate levels of RelA-IκBα retained in inhibitory complexes.

See also Figure S4.

Finally, to assess the role of NF-κB-DNA-binding family members in regulating apoptosis in C4BPA mutants, we evaluated apoptosis following depletion of the DNA-binding NF-κB family members originally identified as C4BPA predicted functional partners by STRING (Figure 1A). In these experiments, we again used our CRISPR KI cells lines as tools to understand the effects of NF-κB family member depletion in cells displaying varying levels of oxaliplatin-induced intracellular C4BPA protein expression. We hypothesized that in those cells with the greatest increases in oxaliplatin-induced C4BPA levels, apoptotic sensitivity and attenuated NF-κB anti-apoptotic responses (such as HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T) depletion of RelA/NF-κB1 would result in minimal additional changes to apoptosis levels. In support of our hypothesis, no changes in apoptosis were observed following RelA depletion in C4BPA-mutant cell line HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T (Figures 4E and 4F). These results were supported by experiments using NF-κB1 siRNA (Figures 4G and S4A). In contrast, as expected, RelA/NF-κB1 depletion experiments showed a marked increase in apoptosis following oxaliplatin treatment in HCT 116 C4BPAWT cells (Figures 3A and 3B). HCT 116 C4BPA563G>A cells were used as a control in RelA depletion experiments. As had been previously observed, apoptosis in these cells never reached the high levels observed in HCT 116 C4BPA182C>T cells and instead remained at an intermediate level between HCT 116 C4BPAWT and C4BPA182C>T cells (Figure 4E). These data are in line with the lack of oxaliplatin-induced C4BPA expression in these cells. These data further support our hypothesis that cells with increased C4BPA protein expression following oxaliplatin treatment display increased apoptosis due to impaired or inhibited NF-κB signaling.

Together these results highlight the importance of studying mutations in innate immunity-associated genes as a tool to uncover novel functions. Using this approach, we identify that C4BPA has cancer-associated functions that are distinct from its canonical role in the complement system. Specifically, we reveal that C4BPA functions as a ‘rheostat,’ regulating oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis through modulation of NF-κB signaling (Figure 4H).

Discussion

Innate immunity-associated proteins with intracellular functions, such as TREX1, cGas, and STING, are emerging as important contributors to treatment response and tumor progression (Cai et al., 2014; Vanpouille-Box et al., 2017; Dunphy et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018). However, despite the rising interest in tumor cell-intrinsic functions for innate immunity-associated proteins, there is a lack of studies investigating the intracellular roles of extracellular innate immunity-associated proteins and what regulates their intracellular expression.

Here, we show that C4BPA is expressed intracellularly in a stress-responsive and mutation-dependent manner. Using the study of specific C4BPA mutations found in patients, we uncover an unexpected, likely immune-independent function for C4BPA. Experimentally, in vitro and/or in vivo, we show that intracellular C4BPA expression in different C4BPA-mutant backgrounds appears to function as a ‘rheostat,’ tipping the balance toward increased apoptosis following oxaliplatin treatment. In these experiments, cells harboring C4BPA mutation (563G > A), with minimal increased stress-responsive C4BPA intracellular expression, as expected, displayed a weaker apoptotic response and tumor regression in vivo than a sensitive mutation (182C > T) displaying increased stress-responsive C4BPA intracellular expression. These data are in line with increased C4BPA intracellular expression tipping the balance toward increased apoptosis. It is important to note, however, that while cells harboring C4BPA mutation (563G > A) displayed a lower apoptotic response than those harboring sensitive C4BPA mutation (182C > T), these cells still showed a trend toward increased apoptosis in comparison to WT cells. These data probably reflect the fact that C4BPA levels following oxaliplatin treatment in these cells remained higher than those of WT cells.

Mechanistically, we show that the increased apoptosis observed in oxaliplatin-sensitive C4BPA mutants is associated with attenuated NF-κB-dependent anti-apoptotic responses. We propose that in cells with increased stress-responsive C4BPA intracellular expression, transcriptionally active NF-κB proteins are impaired due to the elevated expression levels of NF-κB inhibitory proteins. Indeed, following oxaliplatin treatment, we observed increased expression of cytoplasmic inhibitory NF-κB protein, IκBα, in sensitive C4BPA-mutant cells as well as increased IκBα-RelA complexes. These cells also displayed decreased NF-κB reporter activity. We propose that increased C4BPA protein levels following oxaliplatin treatment could contribute to increased stability of IκBα-RelA complexes.

Links between NF-κB activation and complement, specifically C3, have been recently suggested in the context of Alzheimer's disease and viral and bacterial infections (Lian et al., 2014; Tam et al., 2014). However, no associations between these two pathways and how they may cooperate to regulate apoptosis have been suggested in a cancer context, which likely reflects the fact that intracellular roles for complement proteins have only recently been considered (Liszewski et al., 2013; Arbore et al., 2017; Elvington et al., 2017; Kremlitzka et al., 2019). Of note, a recent study reported that complement factor properdin may act as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer models by upregulating ER-activated pro-apoptotic transcription factor DDIT3 (Block et al., 2019). Furthermore, Complement C1q-Binding Protein (C1QBP) was recently shown to play an important role in the DNA damage response by binding, stabilizing, and controlling MRE11's nuclease activity (Bai et al., 2019). These studies, like ours, highlight the importance of investigating intracellular functions of complement proteins.

Interestingly, C4BP can bind DNA mainly through a patch of positively charged amino acids on C4BPA (Trouw et al., 2005). We did not investigate the DNA binding capabilities of C4BPA in our models. However, given that intracellular C4BPA is primarily localized in the cytoplasmic/extranuclear space, it would be interesting to investigate whether C4BPA can bind cytosolic nucleic acids in future studies. Since the environment of the cytoplasm is distinct from that of the extracellular space, it is possible that the structural features of intracellular C4BPA might be different from those of C4BPA present extracellularly (López-Mirabal and Winther, 2008). Interestingly, Hofmeyer et al. reported that the C4BPA heptamer is very stable due to a large number of hydrophobic interactions and formation of electrostatic, disulfide, and hydrogen bonds (Hofmeyer et al., 2013). Whether intracellular C4BPA is present as a single chain or multimer was not investigated in this study. However, it is possible that, even if disulfide bonds are not formed efficiently intracellularly, C4BPA might still be present in a multimeric form as occurs in the main C4BP isoform.

Overall our study provides the first description of stress-specific and mutation-dependent intracellular induction of C4BPA expression in cancer cells and describes the importance of the interplay between C4BPA and NF-κB in regulating oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis sensitivity in colorectal cancer.

Limitations of the Study

Here we uncover that, in colorectal cancer cells, C4BPA has an intracellular role in the regulation of apoptosis following oxaliplatin treatment. Future studies should test a wider range of DNA-damaging agents and cell types. Similarly, testing the effect of C4BPA mutations on tumor progression and treatment response in other tumor models would be interesting, given that C4BPA mutations are associated with improved survival in all epithelial cancer types queried. By studying patient-specific C4BPA mutations, we have focused on the description of an unexpected non-canonical function for C4BPA but have not investigated whether these mutations can impact canonical complement regulation. Furthermore, whether intracellular C4BPA interacts with its canonical ligand/binding partners intracellularly remains to be formally tested. Of note, expression of C4 and C4BPB in the colorectal cancer cell lines used in this study is very low ([Roumenina et al., 2019] and https://www.ebi.ac.uk). We cannot rule out, however, that extracellular C4 or C4BPB could interact with intracellular C4BPA if taken into the cell.

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Monica M. Olcina (monica.olcinadelmolino@uzh.ch).

Materials Availability

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact Monica M. Olcina (monica.olcinadelmolino@uzh.ch).

Data and Code Availability

The published article includes all data sets/code generated or analyzed during this study.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants CA-67166 and CA-197713, the Silicon Valley Foundation, the Sydney Frank Foundation, and the Kimmelman Fund (A.J.G.). M.M.O. was a Cancer Research Institute Irvington Fellow supported by the Cancer Research Institute and Stiftung für Forschung, Medical Faculty, UZH. R.K.K. was supported by Stanford ChEM-H Undergraduate Scholars Program. T.G.G. was supported by the NCI/NIH (P01 CA168585) and an American Cancer Society Research Scholars Grant. M.S. and M.M.O. were supported by a project grant from the Swiss National Foundation (31003A_163141).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.O and A.J.G. Methodology M.M.O, R.K.K and C.G.L. Writing original draft, M.M.O. Writing review and editing, M.M.O, A.J.G, N.G.B, C.G.K and D.R. Investigation, M.M.O, R.K.K and C.G.L. Formal analysis, M.M.O, N.G.B and R.V.E. Resources, A.J.G, T.G.G and M.S. Supervision M.M.O and A.J.G. Funding acquisition, M.M.O, A.J.G, T.G.G ad M.S.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: October 23, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101594.

Supplemental Information

References

- Arbore G., Kemper C., Kolev M. Intracellular complement − the complosome − in immune cell regulation. Mol. Immunol. 2017;89:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Wang W., Li S., Zhan J., Li H., Zhao M., Zhou X.A., Li S., Li X., Huo Y. C1QBP promotes homologous recombination by stabilizing MRE11 and controlling the assembly and activation of MRE11/RAD50/NBS1 complex. Mol. Cell. 2019;75:1299. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkett M., Gilmore T.D. Control of apoptosis by Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6910–6924. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block I., Müller C., Sdogati D., Pedersen H., List M., Jaskot A.M., Syse S.D., Lund Hansen P., Schmidt S., Christiansen H. CFP suppresses breast cancer cell growth by TES-mediated upregulation of the transcription factor DDIT3. Oncogene. 2019;38:4560. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0739-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., Chiu Y.H., Chen Z.J. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing and signaling. Mol. Cell. 2014;54:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Edelstein L.C., Gelinas C. The rel/NF-kappa B family directly activates expression of the apoptosis inhibitor Bcl-xL. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:2687–2695. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2687-2695.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E., Freeman-Mills L., Rayner E., Glaire M., Briggs S., Vermeulen L., Fessler E., Medema J.P., Boot A., Morreau H. Somatic POLE proofreading domain mutation, immune response, and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a retrospective, pooled biomarker study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;1:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunphy G., Flannery S.M., Almine J.F., Connolly D.J., Paulus C., Jønsson K.L., Jakobsen M.R., Nevels M.M., Bowie A.G., Unterholzner L. Non-canonical activation of the DNA sensing adaptor STING by ATM and IFI16 mediates NF-κB signaling after nuclear DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 2018;71:745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvington M., Liszewski M.K., Bertram P., Kulkarni H.S., Atkinson J.P. A C3(H20) recycling pathway is a component of the intracellular complement system. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:970–981. doi: 10.1172/JCI89412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoesel B., Schmid J.A. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2013;12:86. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeyer T., Schmelz S., Degiacomi M.T., Dal Peraro M., Daneschdar M., Scrima A., van den Heuvel J., Heinz D.W., Kolmar H. Arranged sevenfold: structural insights into the C-terminal oligomerization domain of human C4b-binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:1302. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D.W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2008;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D.W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Lin A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:221–227. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremlitzka M., Nowacka A.A., Mohlin F.C., Bompada P., De Marinis Y., Blom A.M. Interaction of serum-derived and internalized C3 with DNA in human B cells-a potential involvement in regulation of gene transcription. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:493. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand A.J., Konstantinou M., Goode E.F., Meier P. The diversification of cell death and immunity: memento mori. Mol. Cell. 2019;76:232. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian H., Yang L., Cole A., Sun L., Chiang A.C., Fowler S.W., Shim D.J., Rodriguez-Rivera J., Taglialatela G., Jankowsky J.L. NFκB-Activated astroglial release of complement C3 compromises neuronal morphology and function associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2014;85:101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liszewski M.K., Kolev M., Le Friec G., Leung M., Bertram P.G., Fara A.F., Subias M., Pickering M.C., Drouet C., Meri S. Intracellular complement activation sustains T cell homeostasis and mediates effector differentiation. Immunity. 2013;39:1143–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang H., Wu X., Ma D., Wu J., Wang L., Jiang Y., Fei Y., Zhu C., Tan R. Nuclear cGAS suppresses DNA repair and promotes tumorigenesis. Nature. 2018;563:131. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Mirabal H.R., Winther J.R. Redox characteristics of the eukaryotic cytosol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1783:629. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie K.J., Carroll P., Martin C.A., Murina O., Fluteau A., Simpson D.J., Olova N., Sutcliffe H., Rainger J.K., Leitch A. CGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature. 2017;548:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nature23449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dea E.L., Barken D., Peralta R.Q., Tran K.T., Werner S.L., Kearns JD, Levchenko A., Hoffmann A. A homeostatic model of IκB metabolism to control constitutive NF-κB activity. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:111. doi: 10.1038/msb4100148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcina M.M., Balanis N.G., Kim R.K., Aksoy B.A., Kodysh J., Thompson M.J., Hammerbacher J., Graeber T.G., Giaccia A.J. Mutations in an innate immunity pathway are associated with poor overall survival outcomes and hypoxic signaling in cancer. Cell Rep. 2018;25:3721–3732.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires I.M., Ward T.H., Dive C. Oxaliplatin responses in colorectal cancer cells are modulated by CHK2 kinase inhibitors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;159:1326–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis E.S., Mastellos D.C., Ricklin D., Mantovani A., Lambris J.D. Complement in cancer: untangling an intricate relationship. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricklin D., Reis E.S., Lambris J.D. Complement in disease: a defence system turning offensive. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016;12:383. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumenina L.T., Daugan M.V., Noe R., Petitprez F., Vano Y.A., Sanchez-Salas R., Becht E., Meilleroux J., Le Clec'h B., Giraldo N.A. Tumor cells hijack macrophage-produced complement C1q to promote tumor growth. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh E.T., Bloch O., Parsa A.T. Complement anaphylatoxins as immune regulators in cancer. Cancer Med. 2014;3:747–758. doi: 10.1002/cam4.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S., Ganchi P., Ballard D., Greene W. NF-κB controls expression of inhibitor IκBα: evidence for an inducible autoregulatory pathway. Science. 1993;259:1912. doi: 10.1126/science.8096091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam J.C., Bidgood S.R., McEwan W.A., James L.C. Intracellular sensing of complement C3 activates cell autonomous immunity. Science. 2014;345:1256070. doi: 10.1126/science.1256070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouw L.A., Nilsson S.C., Gonçalves I., Landberg G., Blom A.M. C4b-binding protein binds to necrotic cells and DNA, limiting DNA release and inhibiting complement activation. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1937. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanpouille-Box C., Alard A., Aryankalayil M.J., Sarfraz Y., Diamond J.M., Schneider R.J., Inghirami G., Coleman C.N., Formenti S.C., Demaria S. DNA exonuclease Trex1 regulates radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15618. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The published article includes all data sets/code generated or analyzed during this study.