Abstract

COVID-19 has resulted in unprecedented global health and economic challenges. The reported mortality in patients with COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation is high. VV ECMO may serve as a lifesaving rescue therapy for a minority of patients with COVID-19; however, its impact on overall survival of these patients is unknown. To date, few reports describe successful discharge from ECMO in COVID-19 after a prolonged ECMO run. The only Australian case of a COVID-19 patient, supported by prolonged VV ECMO in conjunction with prone ventilation, complicated by significant airway bleeding, and successfully decannulated after forty-two days, is described. VV ECMO is a resource-intense form of respiratory support. Providing complex therapies such as VV ECMO during a pandemic has its unique challenges. This case report provides a unique insight into the potential clinical sequelae of COVID-19, supported in an intensive care environment which was not resource-limited at the time, and adds to the evolving experience of prolonged VV ECMO support for ARDS with a goal to lung recovery.

Keywords: extracorporeal life support, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), Coronavirus infection, mechanical ventilation, prone positioning

Introduction

As of the 31st May 2020, Australia has experienced 7202 cases of the SARS CoV-2 virus and 102 related deaths [1]. The reported mortality in patients with COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation is high [2,3]. Veno-venous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (VV ECMO) may serve as a lifesaving rescue therapy, particularly in young patients with single organ failure.

Globally, 813 patients with the SARS CoV-2 virus have been managed with ECMO. Two hundred and sixty-one patients have been decannulated, and of those, 46% have been discharged alive [4].

The only Australian case of COVID-19 supported with prolonged VV ECMO in conjunction with prone ventilation, who was successfully decannulated after forty-one days, is described.

Case Report

A 55-year-old female, height 151cm and weighing 61kg, who recently had returned from the Philippines, presented at a small regional hospital in suburban Sydney, Australia with a one-week history of fever, cough, lethargy and myalgia. On presentation, she was febrile with a temperature of 42oC and gave a past medical history which included mild asthma, sleep apnoea and Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Oral hypoglycaemics had been prescribed for her diabetic condition. She was a non-smoker.

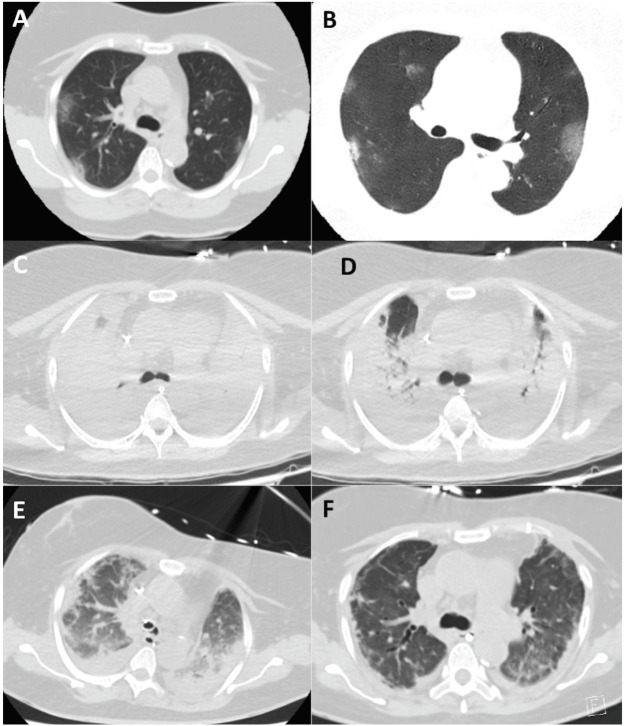

The results of nasopharyngeal swabs, taken at the time of presentation, were found to be SARS CoV-2 PCR positive. A CT chest scan demonstrated patchy bilateral air-space infiltrates with scattered ground glass density consistent with a diagnosis of COVID-19 (Figure 1-A, B).

Fig.1.

CT Chest Axial Imaging demonstrating progression and resolution of lung infiltration. Image A, B - Admission to hospital; C,D - Imaging performed on PEEP of 5 cmH2O and 40 cmH2O respectively;D - on day 13 of ECMO; E- Day 29 of ECMO; F - 13 days post decannulation.

She was transferred for ongoing management to a large quaternary referral centre and university hospital in Metropolitan Sydney, Australia.

Her respiratory status deteriorated on Day 4 of hospital admission requiring transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU), semi-elective intubation and initiation of lung-protective ventilation (Figure 2-A). After that, she progressed to septic shock and multi-organ dysfunction.

Fig.2.

Plain Chest radiographs demonstrating progression and resolution of lung infiltration. A - post intubation; B - initiation of ECMO; C - Day 13 of ECMO; D - Day 20 of ECMO after initiation of proning; E - Day 34 of ECMO; F - 13 days post ECMO decannulation.

On Day 5, her oxygenation and metabolic derangements continued to deteriorate despite a high PEEP, deep sedation and paralysis with the neuromuscular blocker cisatracurium (Pfizer Pty Ltd, Australia) in intravenous bolus doses of 10 mg followed by a continuous infusion. She was then referred for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

At the time of referral, her Fi02 was 90%, PEEP 20 cm of H2O, with a P/F ratio of 62 (Figure 2-B). Echocardiography demonstrated normal left ventricular (LV) systolic function, mild right ventricular (RV) systolic dysfunction, mild RV dilatation and mild to moderate tricuspid regurgitation. The Respiratory Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Survival Prediction Score (RESP) [5] was 1, with a predicted survival of 57%. A decision was made to commence VV ECMO on Day 10 post-admission.

Cannulation was carried out via a femoral-femoral approach using a 21F return cannula and a 23F drainage cannula. Ventilation was reduced to a rest setting of tidal volume 2ml/kg, PEEP 10 cmH2O and a respiratory rate of 10 bpm.

At the time of cannulation, transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) identified a thrombus transiting through the right atrium. Despite this, there was an almost immediate improvement in the patient’s haemodynamic and RV function.

The following clinical events defined her course on ECMO.

Inability to mechanically ventilate

By Day14 post-admission, and after five days of VV ECMO, she had a complete loss of tidal volumes and was ultimately ECMO dependent.

A high-resolution chest CT (HRCT) performed on Day 20 post-admission and after 11 days of VV ECMO, demonstrated a minimal amount of potentially recruitable lung and extensive and near-complete consolidation and collapse of the lungs bilaterally (Figure 1-C, D).

A further HRCT, performed on Day 34 post-admission / Day 25 of VV ECMO, following a period of prone ventilation, demonstrated predominant patchy areas of bilateral consolidation, especially in the peripheral lung tissue, as well as extensive ground glass changes (Figure 1-E).

By Day 34 post-admission and after 25 days of VV ECMO, she was in the position to be transitioned to pressure support ventilation (Figure 2-E).

Pulmonary haemorrhage and sloughing of bronchial tissues with airway obstruction

Airway bleeding leading to complete proximal airway occlusion occurred on Day 23 post-admission/ Day 14 of VV ECMO. At this time, the patient was anticoagulated with intravenous heparin (Hospira Pty Ltd, Australia) as an infusion for the ECMO circuit, and her coagulation profile was consistent with that of mild heparinization, with the Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time measured at 1.5 times the upper limit of normal.

The airway bleeding was treated with nebulised tranexamic acid (Pfizer Pty Ltd, Australia) 500 mg of the intravenous solution and the cessation of heparin (Hospira Pty Ltd, Australia).

On Day 23 post-admission / Day 14 of VV ECMO, following bronchoscopic removal of thrombus, fibrous tissue strands extending proximally into both main stem bronchi were observed via further bronchoscopy.

Cryotherapy was performed on Day 23 post-admission/ Day 14 of VV ECMO along with direct injection of tranexamic acid (Pfizer Pty Ltd, Australia)1g of the intravenous solution injected intravenous-intrabronchial and epinephrine (Juno pharmaceuticals, Australia),500 micrograms of 1:10,000 intravenous solution injected intra-bronchially.

Cytology of the bronchial tissue, taken on Day 23 post-admission, day 14 of VV ECMO revealed bronchial cells. Due to ongoing oozing in the right lower lobe, lung isolation with a bronchial blocker and later a double-lumen endotracheal tube was performed. This treatment was continued for the next three days. Repeat bronchoscopy on Day 26 post-admission / Day 17 of VV ECMO demonstrated ongoing albeit reduced bleeding and ongoing sloughing of the bronchial mucosa.

Argon plasma coagulation (APC) was also used to remove fibrin debris obstructing main stem bronchi, facilitating bilateral lung recruitment. (Figure 2-C).

Prone Ventilation

Once airway bleeding had stabilised, prone ventilation was commenced on Day 27 post-admission, day 18 of VV ECMO aiming to facilitate ongoing lung recruitment (Figure 2-D). By the fifth cycle of prone ventilation, a chest X-ray (CXR) demonstrated an improvement in the aeration of lung fields. Prone ventilation was typically well tolerated with minimal cardiorespiratory support.

ECMO circuit change out

Active surveillance for haemolysis revealed an elevated D-dimer on Day 37 post-admission and Day 28 of VV ECMO, SWEEP requirements and trans-membrane pressures all remained within normal limits. Minimal areas of thrombus were observed peripherally on the oxygenator membrane. By Day 39 post-admission / Day 30 of VV ECMO, laboratory tests showed clear evidence of haemolysis. This was resolved following an uneventful oxygenator change out.

Hypercalcaemia

In the late phase of the ECMO run, the patient developed persistently high calcium levels, with a peak blood level of 3.26 mmol/L on Day 32 post-admission/Day 23 of VV ECMO. Further investigations were performed to determine the cause, including parathyroid hormone levels, serum phosphate, 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D and thyroid hormone levels. These were all noted to be within the normal range. The condition was treated with pamidronate disodium (Hospira Pty Ltd, Australia), 60 mg given on Day 33 post-admission and Day 24 of VV ECMO and calcitonin (Emerge Health Pty Ltd, Australia), 100 units thrice daily for seven days, starting on Day 33 post-admission/ Day 24 of VV ECMO with normalisation of the calcium levels by Day 45 post-admission/Day 36 of VV ECMO.

Decannulation

On Day 40 post-admission and 31 days of VV ECMO, trials of weaning the ECMO support were initiated to transit the patient off VV ECMO onto conventional ventilator support.

The final trial of decreased ECMO gas flow was continued for 27 hours with stable gas exchange.

On Day 51 post-admission and 42 days of VV ECMO, the patient was transferred to the operating theatre where the ECMO cannulas were removed. At the same time, an open repair of the femoral veins was undertaken by the vascular surgery team.

Subsequent progress

From Days 52-62 post-admission and after 21 days post-ECMO decannulation, the patient slowly continued to improve. A surgical tracheostomy was undertaken on Day 55 post-admission and after seven days of ECMO decannulation, to facilitate ongoing pulmonary rehabilitation. After that, she was successfully weaned off ventilator support. She was able to phonate via insufflation of oxygen into the supraglottic port of the tracheostomy tube (Figure 1-F and 2-F). By Day 60 post-admission, from a neurological perspective, she was awake, obeying commands, actively participating in her rehabilitation and interacting with her family.

Discussion

Providing complex therapies such as VV ECMO during a pandemic has its unique challenges. VV ECMO is a resource-intense form of respiratory support. Extracorporeal resources during a pandemic can become rapidly overwhelmed, posing ethical challenges as to timing and determination of which patients receive support [6]. Case numbers of COVID-19 in Australia have remained low, and ICUs have not exceeded their capacity, allowing VV ECMO to be offered to eligible patients in keeping with both WHO and Australian guidelines [7,8].

However, while ECMO is one of the treatment options in severe ARDS and was utilised effectively during the H1N1, SARS and MERS pandemics [9], its role in the management of COVID-19 remains unclear [10].

The data regarding mortality, complications and duration of ECMO support in COVID-19 remains incomplete. In one series Sultan (2020) described two patients successfully taken off support ECMO and seven patients remaining on support [12]. In their case series, both Ruan (2020) [13] and Yang [11] both describe a 100% mortality among patients supported by ECMO.

In one of the more extensive reported case series describing thirty-two patients supported with ECMO, five patients were successfully taken off support, and seventeen patients remained on ECMO [14]. Amongst those no longer on ECMO, the longest ECMO run was fifteen days. It is currently too early to appreciate the anticipated clinical course and duration of ECMO support in these patients or the effect this intensive form of respiratory support will have on the outcome.

However, the patient described in the presented case report, had a 41-day ECMO run, in a setting of predominantly single-organ failure and continued to improve three-weeks post-decannulation. A unique aspect of this case is the prolonged use of ECMO. Whilst the efficacy of VV ECMO is well recognised as a bridge to lung recovery in ARDS, the evidence supporting the use of prolonged ECMO runs in this setting is not so well established. The ELSO Registry (2016) reported that the average ECMO run for viral pneumonia was 13.5 days [15].

The ELSO registry data from 2009 to 2018 reported 4,361 adult patients who underwent prolonged ECMO for respiratory failure, 88% of which received VV ECMO. The median ECMO duration was 22 days with a mean of 28±20 days. Prolonged ECMO periods varied, with over 30% being longer than one month. Overall survival to hospital discharge was 51%, and the duration of ECMO support did not differ between survivors and non-survivors [16]. Other studies have shown that prolonged ECMO support was not an independent risk factor for increased mortality [15, 17, 18, 19]. There has been a significant improvement in prolonged ECMO survival over recent years due to technological advances, experience and better prevention and management of complications. While the assessment to continue ECMO support in this patient population is multifactorial, time on ECMO should not be the sole factor in this challenging decision.

The use of prone positioning has been demonstrated to improve oxygenation as well as survival in patients with severe ARDS and refractory hypoxaemia [20, 21]. While ultra-protective ventilation is used in ARDS-patients on VV ECMO [22], it results in increased alveoli collapse and therefore, poor ventilation of the dependent lung tissue [23].

Unfortunately, the patient in the present case report initially was unable to be proned due to haemodynamic instability. Eventually, when the patient became more stable, successive 16-hour sessions of prone positioning over seven days was performed. Her tidal volumes improved from 40-50 ml to 250-300 ml with acceptable driving pressures. Progress CT chest demonstrated marked improvement of the bilateral collapse/consolidation with no overt signs of fibrosis [Figure 1-E]. In this patient, proning was an essential aspect of being able to commence and sustain ECMO weaning.

Anticoagulation management was challenging for this patient, due to the need to balance the competing goals of minimising clot formation within the ECMO circuit with major airway bleeding in a prothrombotic milieu of COVID-19 infection [2].

After one month on ECMO, a rising lactate dehydrogenase, d-dimer, bilirubin and falling fibrinogen were noted. In contrast, transmembrane pressures were low and stable, the post-membrane PO2 was > 400mmHg [53kPa], and there were only minor visible clots peripherally on the oxygenator membrane. Despite seemingly optimal oxygenator function, given the biochemical evidence of haemolysis, it was decided to replace the oxygenator with resultant rapid resolution of the markers of haemolysis.

Several reviews correlate the causes of haemolysis during ECMO support with either high negative access pressures, high pump flows, small cannula size, or pump head thrombosis and high transmembrane pressures with a loss of oxygen transfer [24, 25, 26]. It is interesting to note that haemolysis occurred in this case in the absence of all of these factors.

In the late phase of her ECMO run, the patient developed persistent hypercalcemia with normal parathyroid hormone, phosphate, 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D and thyroid hormone levels. This was attributed to prolonged bed rest and immobilisation, resulting in excessive bone resorption.

Another consideration is that of heparin-induced osteoclastic bone resorption, given her prolonged time on ECMO, requiring extended therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin. Hypercalcaemia is a well-documented complication of prolonged ECMO support in both neonatal and paediatric populations but has not been described in adults on prolonged ECMO support [27,28]. The hypercalcemia in our patient was attributed to prolonged bed rest and immobilisation, resulting in excessive bone resorption. Another consideration is that of heparin-induced osteoclasts bone resorption, given her prolonged time on ECMO requiring extended therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin.

This case report provides a unique insight into the potential clinical sequelae of COVID-19 infection, supported in an intensive care environment which was not resource-limited at the time. The case adds to the evolving experience of prolonged VV ECMO support for ARDS with a goal of native lung recovery.

Acknowledgements

All Medical, Nursing, Allied health, Social work and support staff of Westmead Intensive Care Service

ECMO service Westmead Hospital

Infectious diseases department Westmead hospital

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare.

References

- 1.Coronavirus (COVID-19) current situation and case numbers [Internet] Australia: Department of Health;; https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers [reviewed 2020 Apr 15; cited 2020 Jun 10]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowalewski M, Fina D, Slomka A. COVID-19 and ECMO: the interplay between coagulation and inflammation-a narrative review. Crit Care. 2020;24:205. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02925-3. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Full COVID-19 Registry Dashboard [Internet]. Michigan: ELSO registry; [reviewed 2020 Apr 20; cited 2020 Jun 10] https://www.elso.org/Registry/FullCOVID19RegistryDashboard.aspx Available from.

- 5.Schmidt M, Bailey M, Sheldrake J. Predicting survival after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory failure. The Respiratory Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Survival Prediction (RESP) score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1374–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-2023OC. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartlett RH, Ogino MT, Brodie D. Initial ELSO Guidance Document: ECMO for COVID-19 Patients with Severe Cardiopulmonary Failure. ASAIO J. 2020;66:472–4. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001173. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian guidelines for the clinical care of people with COVID-19 v6.0 [Internet] Australia: National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce; https://covid19evidence.net.au [reviewed 2020 May 10; cited 2020 Jun 10]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection ( SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected: interim guidance [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330893 [updated 2020 Mar 13; cited 2020 Jun 10]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies A, Jones D, Bailey M. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for 2009 Influenza A(H1N1) Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. JAMA. 2009;302:1888–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1535. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng Y, Cai Z, Xianyu Y, Yang BX, Song T, Yan Q. Prognosis when using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for critically ill COVID-19 patients in China: a retrospective case series. Crit Care. 2020;24:148. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2840-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centre, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sultan I, Habertheuer A, Usman AA. The role of extracorporeal life support for patients with COVID-19: Preliminary results from a statewide experience. J Card Surg. 2020;35:1410–3. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14583. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:846–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs JP, Stammers AH, St Louis J. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Treatment of Severe Pulmonary and Cardiac Compromise in Coronavirus Disease 2019: Experience with 32 Patients. ASAIO J. 2020;66:722–30. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001185. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiagarajan RR, Barbaro RP, Rycus PT. Extracorporeal Life Support Organisation Registry International Report 2016. ASAIO J. 2017;63:60–7. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000475. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Posluszny J, Engoren M, Napolitano LM, Rycus PT, Bartlett RH. Predicting Survival of Adult Respiratory Failure Patients Receiving Prolonged (≥14 Days) Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2020;66:825–33. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camboni D, Philipp A, Lubnow M. Support time-dependent outcome analysis for veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:1341–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.03.062. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kon ZN, Dahi S, Evans CF. Long-Term Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:2059–63. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.05.088. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menaker J, Rabinowitz RP, Tabatabai A. Veno-Venous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Respiratory Failure: How Long Is Too Long? ASAIO J. 2019;65:192–6. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000791. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gattinoni L, Carlesso E, Taccone P, Polli F, Guerin C, Mancebo J. Prone positioning improves survival in severe ARDS: a pathophysiologic review and individual patient meta-analysis. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:448–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sud S, Friedrich JO, Taccone P. Prone ventilation reduces mortality in patients with acute respiratory failure and severe hypoxemia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:585–99. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1748-1. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rozencwajg S, Guihot A, Franchineau G. Ultra-Protective Ventilation Reduces Biotrauma in Patients on Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:150512. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003894. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimmoun A, Guerci P, Bridey C, Ducrocq N, Vanhuyse F, Levy B. Prone positioning use to hasten veno-venous ECMO weaning in ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1877–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appelt H, Philipp A, Mueller T. Factors associated with hemolysis during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)-Comparison of VA- versus VV ECMO. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227793. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubnow M, Philipp A, Foltan M. Technical complications during veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and their relevance predicting a system-exchange--a retrospective analysis of 265 cases. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112316. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams DC, Turi JL, Hornik CP. Circuit oxygenator contributes to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-induced hemolysis. ASAIO J. 2015;61:190–5. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000173. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fridriksson JH, Helmrath MA, Wessel JJ, Warner BW. Hypercalcemia associated with extracorporeal life support in neonates. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:493–7. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.21608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rambaud J, Guellec I, Guilbert J, Leger PL, Renolleau S. Calcium homeostasis disorder during and after neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2015;19:513–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.164797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]