ABSTRACT

Between embryonic days 10.5 and 14.5, active proliferation drives rapid elongation of the murine midgut epithelial tube. Within this pseudostratified epithelium, nuclei synthesize DNA near the basal surface and move apically to divide. After mitosis, the majority of daughter cells extend a long, basally oriented filopodial protrusion, building a de novo path along which their nuclei can return to the basal side. WNT5A, which is secreted by surrounding mesenchymal cells, acts as a guidance cue to orchestrate this epithelial pathfinding behavior, but how this signal is received by epithelial cells is unknown. Here, we have investigated two known WNT5A receptors: ROR2 and RYK. We found that epithelial ROR2 is dispensable for midgut elongation. However, loss of Ryk phenocopies the Wnt5a−/− phenotype, perturbing post-mitotic pathfinding and leading to apoptosis. These studies reveal that the ligand-receptor pair WNT5A-RYK acts as a navigation system to instruct filopodial pathfinding, a process that is crucial for continuous cell cycling to fuel rapid midgut elongation.

KEY WORDS: Gut elongation, RYK, ROR2, WNT5A, Interkinetic nuclear migration, Pseudostratified

Highlighted Article: Fetal gut elongation is crucial for proper postnatal nutrient absorption. Wnt5a, Ryk and Ror2 mouse mutants reveal that WNT5A receptors are important for rapid gut elongation.

INTRODUCTION

The adult human small intestine (SI) is a long coiled tube, measuring 5.5 m on average (Weaver et al., 1991). This remarkable length is crucial for providing the large surface area needed for sufficient nutrient absorption. To achieve this great length, active SI elongation begins in utero, which ensures that the SI acquires an adequate length (over 40% of its adult length) at birth to meet postnatal nutritional demands. Infants that are born with significantly shorter SIs, a disorder known as congenital short bowel syndrome (CSBS), fail to thrive (Hasosah et al., 2008), supporting the significance of SI elongation during the fetal stage. However, the causes of CSBS, as well as the detailed mechanisms underlying the rapid elongation of the fetal SI remain largely unexplored.

The SI is derived from the midgut during embryogenesis. In the mouse embryo, the midgut arises from the middle region of the primitive gut tube by E10 (Zorn and Wells, 2009). Shortly afterwards, this tiny midgut primordium (<1.5 mm) begins to rapidly elongate in two phases. In Phase I (E10.5-E14.5), the midgut is a simple tube with a narrow lumen; it rapidly increases its length by 11-fold and slowly gains girth (Wang et al., 2018). In Phase II (E14.5-E18.5), finger-like villi begin to emerge (Freddo et al., 2016; Walton et al., 2016), quickly changing the epithelial structure and expanding the luminal surface area; elongation continues but at a slower rate (<4-fold in four days) (Wang et al., 2019).

During Phase I, the midgut epithelium is pseudostratified and its accelerating elongation is driven by active cell division, which is tied to a process called interkinetic nuclear migration (IKNM) (Grosse et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2018). During IKNM, nuclei migrate in accordance with the cell cycle, entering S phase near the basal surface and traveling apically to divide (Norden, 2017). The constant nuclear movement allows cells to take turns initiating mitotic cell rounding at the very limited apical surface (Miyata et al., 2015). Although efficient, this peculiar cell division behavior nevertheless faces some challenges. After apical mitosis, daughter nuclei need to quickly exit the crowded apical zone and return to the basal side to synthesize DNA for the next round of division. However, only one of the two daughter cells inherits a basal connection from the mother cell; many heirs can directly exploit this basal connection as a ‘conduit’ to directly transport their nuclei to the basal side. However, more than half of the daughter cells use a ‘pathfinding’ strategy: they must first grow a filopodial protrusion to establish a new basal path and then use that path to deliver their nuclei basally. Importantly, WNT5A, which is secreted by the underlying mesenchymal cells, acts as a guidance cue to facilitate efficient pathfinding. Without WNT5A, filopodial pathfinding is impaired; some cells remain trapped apically, leading to increased apoptosis and a shortened midgut (Wang et al., 2018).

How midgut epithelial cells recognize and respond to the mesenchymal WNT5A cue is unknown. WNT5A plays diverse roles by triggering various intracellular signaling cascades upon the engagement of different receptors (Kikuchi et al., 2012). In this study, we specifically focused on the receptors ROR2 and RYK, both of which are single-pass transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) proteins. ROR2 binds WNT5A through its extracellular frizzled like cysteine-rich domain (Oishi et al., 2003) whereas RYK binds WNT5A via its extracellular WNT inhibitory factor (WIF) domain (Keeble et al., 2006; Yoshikawa et al., 2003).

ROR2 is widely appreciated as a critical receptor of WNT5A signaling (Green et al., 2014). Ror2−/− and Wnt5a−/− embryos share similar defects in many outgrowing structures, although the Ror2−/− phenotype is somewhat milder (Oishi et al., 2003; Suzuki et al., 2003; Takeuchi et al., 2000; Yamaguchi et al., 1999). Importantly, Yamada et al. found that the Ror2−/− midgut is shortened and widened; they proposed that ROR2 directs an epithelial convergent extension process that is required for midgut elongation (Yamada et al., 2010). However, more recent evidence suggests that epithelial convergent extension does not occur in Phase I (Wang et al., 2018). Interestingly, ROR2 mediates WNT5A-induced filopodia formation in several types of cultured cells (Nishita et al., 2006). This raises the possibility that ROR2 participates in gut elongation as an epithelial WNT5A receptor, to sense directional cues and instruct the filopodial outgrowth of pathfinding cells. Still, the Ror2−/− gut is not as short as the Wnt5a−/− gut (63% versus 28% of wild type at E13.5) (Wang et al., 2018; Yamada et al., 2010), suggesting that additional receptors may participate.

RYK is a less studied WNT5A receptor. Similar to Wnt5a- and Ror2-null embryos, Ryk−/− embryos have outgrowth defects in multiple organs (Halford et al., 2000; Kugathasan et al., 2018), but no gut phenotype has been described. Importantly, in mouse forebrain, RYK is responsible for establishing an appropriate axon trajectory guided by WNT5A (Keeble et al., 2006). Thus, RYK is another promising candidate for pathfinding cells to sense the WNT5A cue in the pseudostratified midgut epithelium.

Here, we demonstrate that epithelial ROR2 is not required for midgut elongation, contradicting the previous model (Yamada et al., 2010). Instead, using detailed 3D confocal imaging and 2D live imaging, we detect pathfinding aberrations in the Ryk−/− gut epithelium that mirror those seen in the Wnt5a−/− gut, suggesting that the RYK receptor is crucial for the basally oriented extension of filopodial protrusions in response to WNT5A.

RESULTS

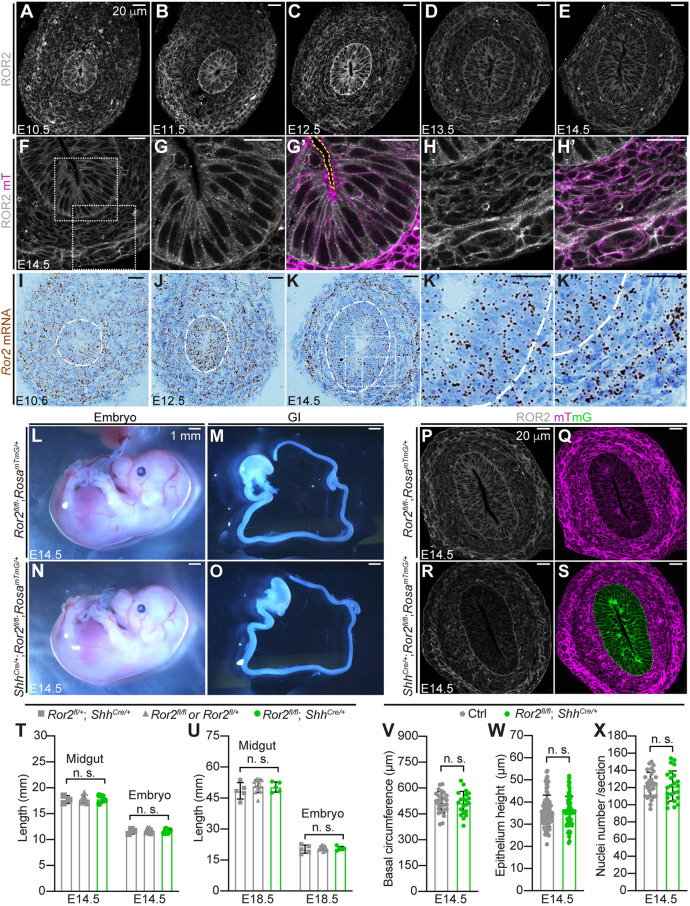

Ror2 is expressed in both mouse midgut epithelium and mesenchyme, but epithelial ROR2 is dispensable for gut elongation

To test the hypothesis that ROR2 acts as a WNT5A receptor to facilitate efficient ‘pathfinding’ in Phase I midguts, we first analyzed the ROR2 expression pattern between E10.5 and E14.5 using immunohistochemistry. Consistent with a previous report (Yamada et al., 2010), ROR2 is present in both midgut epithelium and mesenchyme throughout Phase I (Fig. 1A-E). In the epithelium, ROR2 expression is more intense from E10.5 to E12.5, peaking at E12.5 and decreasing thereafter (Fig. 1A-E, Fig. S1A). In the epithelium, ROR2 is absent at the apical surface and restricted to the basolateral membrane of all cells (Fig. 1F,G′). In the mesenchyme, ROR2 is present on the entire cell membrane of nearly all cells, with varying intensity (Fig. 1H,H′). The expression pattern of Ror2 mRNA was consistent with these findings (Fig. 1I-K″).

Fig. 1.

Ror2 is expressed in both midgut epithelium and mesenchyme, but epithelial Ror2 is dispensable for gut elongation. (A-E) Immunostaining of ROR2 (white) on cross-sections of the central wild-type midgut at E10.5-E14.5. Scale bars: 20 µm. (F-H′) Immunostaining of ROR2 (white) and fluorescence of membrane tdTomato (magenta) on E14.5 midgut sections. (G-H′) Higher magnifications of boxed epithelial (G,G′) and mesenchymal (H,H′) regions in F. In G′, the yellow dashed line outlines the apical surface. Scale bars: 20 µm. (I-K″) RNAscope in situ hybridization with probes for Ror2 on cross-sections of the central midgut at E10.5, E12.5 and E14.5. (K′,K″) Higher magnifications of the boxed epithelial (K′) and mesenchymal (K″) regions in K. The epithelial-mesenchymal interface is outlined by dashed white lines. Scale bars: 20 µm. (L-O) E14.5 embryos and isolated gastrointestinal (GI) tracts of the control (L,M) and epithelial Ror2 knockout (N,O). Scale bars: 1 mm. (P-S) Immunostaining of ROR2 (white) and fluorescence of membrane tdTomato (magenta) and membrane eGFP (mG, green) on cross-sections of control (P,Q) and epithelial Ror2 knockout (R,S) midgut at E14.5. Scale bars: 20 µm. (T,U) Quantitation of midgut length (from the pylorus to the cecum) and crown-rump length of embryos at E14.5 (T) and E18.5 (U) with (gray) or without (green) epithelial ROR2. At E14.5, Ror2flox/+; ShhCre/+, n=3; Ror2flox/flox and Ror2flox/+, n=6; Ror2flox/flox; ShhCre/+, n=4. At E18.5, Ror2flox/+; ShhCre/+, n=4; Ror2flox/flox and Ror2flox/+, n=12; Ror2flox/flox; ShhCre/+, n=4. (V-X) Quantitation of basal circumference, epithelial height and nuclei number on cross-sections of the central midgut epithelial tubes with or without epithelial ROR2. Quantification was performed on 25 sections of five control samples and 20 sections of four Ror2flox/flox; ShhCre/+ samples. For the basal circumference and nuclei number, one measurement was taken per section; for the epithelial height, three or four measurements were taken per section. Data are mean±s.e.m. Analyses were performed using unpaired nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney test). n.s., not significant.

To better elucidate the role of epithelial ROR2 in midgut elongation, we took advantage of a Ror2 floxed allele (Ho et al., 2012) that can be deleted in specific lineages using appropriate Cre drivers. Shh is expressed in the epithelium of the primitive gut tube as early as E8.5 (Bitgood and Mcmahon, 1995; Mao et al., 2010) and the ShhCre transgene (Harfe et al., 2004) can direct recombination in all gut epithelial cells (Mao et al., 2010). Therefore, we bred Ror2flox/flox; RosamTmG/mTmG mice with Ror2flox/+; ShhCre/+ to achieve early gut epithelium-specific depletion of Ror2. The specificity of Cre activity was confirmed by crossing ShhCre/+ to RosamTmG/mTmG reporter mice (Fig. 1Q,S) and depletion of ROR2 was confirmed by antibody staining (Fig. 1P,R). Surprisingly, after epithelial Ror2 depletion, no gross defects were observed either in embryos or guts at E14.5 (Fig. 1L-O). Measurements demonstrated that, neither embryo size nor average midgut length was changed at E14.5 (Fig. 1T). Even at E18.5, just before birth, no changes were detected (Fig. 1U). Furthermore, we measured the basal circumference of the midgut epithelial tube (Fig. 1V), the epithelial height (Fig. 1W) and epithelial cell number on cross-sections (Fig. 1X), and no morphological changes were observed. Additionally, no significant changes in epithelial mitotic or apoptotic rates (Fig. S1B-D) were detected after epithelial Ror2 depletion. Altogether, these results indicate that epithelial ROR2 is dispensable for midgut elongation.

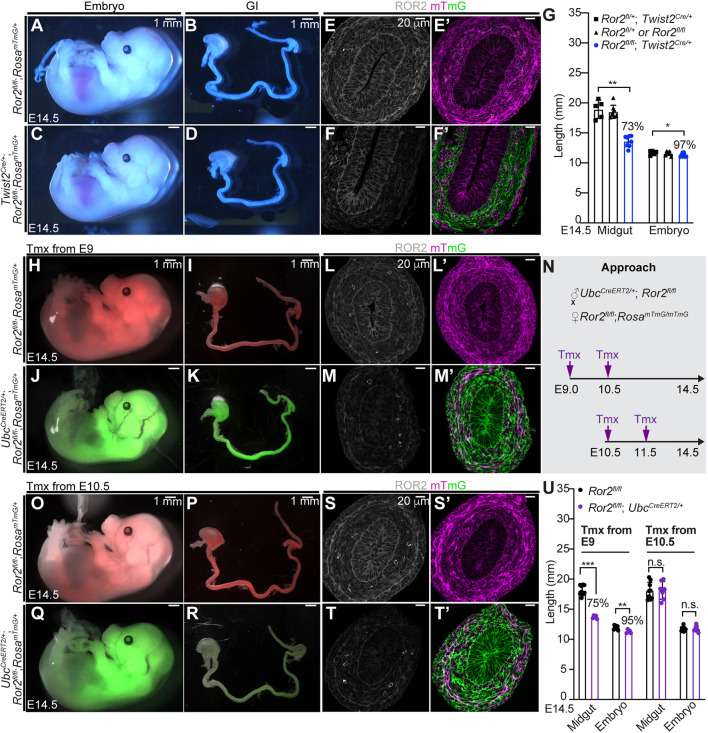

Mesenchymal ROR2 is required for midgut elongation before Phase I

The above results suggest that loss of Ror2 in other (non-epithelial) compartments may account for the gut lengthening defects previously seen in Ror2−/− mutants (Yamada et al., 2010). We therefore depleted Ror2 in gut mesenchyme, using a Twist2Cre driver, which is active as early as E9.5 and confined to mesodermal tissues (Yu et al., 2003). The specificity of Twist2Cre activity was confirmed using a mTmG reporter (Fig. 2E′,F′) and mesenchymal ROR2 depletion was confirmed by antibody staining (Fig. 2E,F). Although Ror2−/− embryos were reported to be 80-90% of control size (Takeuchi et al., 2000), Ror2flox/flox; Twist2Cre/+ embryos were only slightly smaller (Fig. 2A,C,G); nevertheless, the two models exhibit similar phenotypes, including shortened limbs, tail, maxilla and mandible (Fig. 2C). Importantly, Ror2flox/flox; Twist2Cre/+ midguts measured 73±5% of control length at E14.5 (Fig. 2B,D,G), very close to the documented Ror2−/− midgut length (60-70% of control length). Thus, mesenchymal Ror2 is important for midgut elongation.

Fig. 2.

Mesenchymal ROR2 is required for midgut elongation before Phase I. (A-D) E14.5 embryos and GI tracts of control (A,B) and mesenchymal Ror2 knockout (C,D). Scale bars: 1 mm. (E-F′) Immunostaining of ROR2 (white) and fluorescence of mT (magenta) and mG (green) on cross-sections of control (E,E′) and mesenchymal Ror2 knockout (F,F′) midguts at E14.5. Scale bars: 20 µm. (G) Quantitation of midgut length and embryo length of control (black) and mesenchymal Ror2 knockout (blue) at E14.5. Ror2flox/+ ;Twist2Cre/+, n=5; Ror2flox/flox and Ror2flox/+, n=8; Ror2flox/flox; Twist2Cre/+, n=8. (N) Experimental approach for temporal ROR2 depletion by tamoxifen administration to mouse dams starting at E9 or at E10.5. (H-K,O-R) E14.5 embryos and GI tracts with tamoxifen treatment starting at E9 (H-K) or E10.5 (O-R). Scale bars: 1 mm. (L-M′,S-T′) Immunostaining of ROR2 (white) and fluorescence of mT (magenta) and mG (green) on E14.5 midgut sections of the control (L,L′,S,S′) and ROR2 depletion beginning at E9 (M,M′) or E10.5 (T,T′). Scale bars: 20 µm. (U) Quantitation of midgut length in control embryos (black) and embryos with ROR2 depletion starting at E9 or E10.5 (purple). For tamoxifen treatment from E9, Ror2flox/flox, n=9; Ror2flox/flox; UbcCreERT2/+, n=5. For tamoxifen treatment from E10.5, Ror2flox/flox, n=9; Ror2flox/flox; UbcCreERT2/+, n=7. Data are mean±s.e.m. Analyses were performed using unpaired nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney test). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n.s., not significant.

Ror2 is expressed in the gut beginning at E9.5 (Yamada et al., 2010) and transcripts remain present throughout the rest of the fetal stage (Fig. S2A-C). To investigate when ROR2 is required for gut elongation, we induced Ror2 depletion in Ror2flox/flox; UbcCreERT2/+; RosamTmG/+ embryos at different time points (Fig. 2N). Strikingly, the administration of tamoxifen from E9 yielded phenotypes closely resembling those of Ror2−/− mutants and a 25% reduction in midgut length (Fig. 2H-M′,U). However, the same dose of tamoxifen starting at E10.5 or later did not decrease midgut length, although a shorter mandible and mild defects in other structures were seen (Fig. 2O-T′,U). These data suggest that mesenchymal ROR2 plays a role in midgut elongation during the initial primordial stage, but not thereafter.

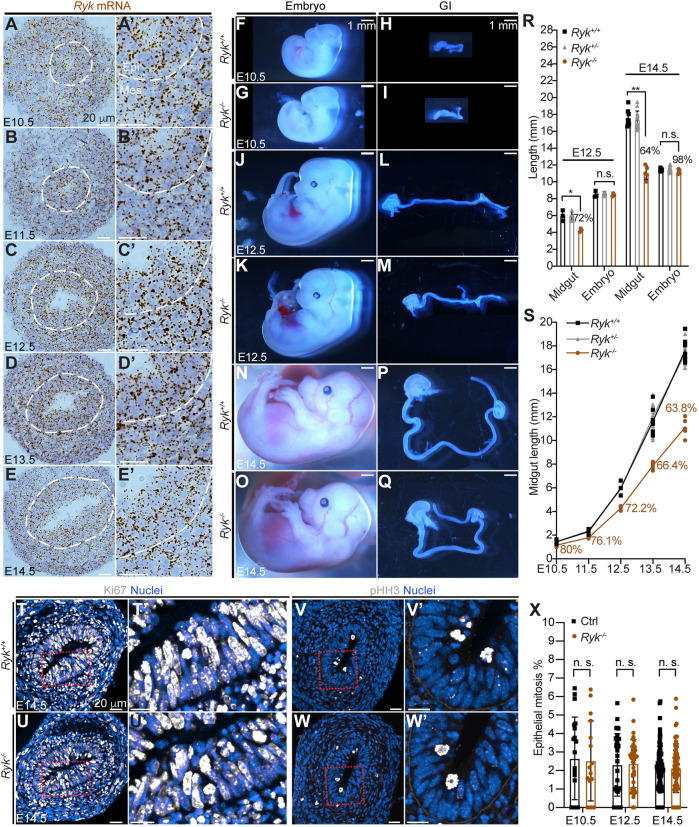

RYK is required for midgut elongation throughout Phase I

After ruling out an essential role for epithelial ROR2 in midgut elongation, we next investigated another potential WNT5A receptor: RYK. Owing to the lack of antibodies that can specifically detect RYK protein by immunostaining, the RNAscope assay was performed to detect Ryk mRNA in the midgut. From E10.5 to E14.5, Ryk expression was relatively homogenous and Ryk mRNAs were present in every epithelial cell and nearly all mesenchymal cells (Fig. 3A-E′). Next, we obtained Ryk−/−, Ryk+/− and wild-type embryos. Consistent with a previous report (Halford et al., 2000), Ryk+/− embryos were indistinguishable from wild type, but Ryk−/− embryos exhibited a flattened midface and a shortened mandible (Fig. 3F,G,J,K,N,O). Importantly, a significant reduction in midgut length was seen in Ryk−/− embryos and this length deficit was progressive throughout Phase I, from 80% of control length at E10.5, to 63.8% at E14.5 (Fig. 3H,I,L,M,P,Q,S). Of note, reduced midgut length was not due to delayed development or to an overall decrease in embryo size, as the Ryk−/− mutant was only slightly smaller than wild type (not significant before E12.5, 98% of control at E14.5) (Fig. 3R). After E14.5 (beginning of Phase II), Ryk mRNAs were still present in the midgut (Fig. S3A-C) but the fraction of Ryk−/− midgut length versus control length remained ∼64-67% and did not decline further (Fig. S3D). Similarly, Wnt5a−/− midguts are short at E10.5, and length deficits increase throughout Phase I (Wang et al., 2018), but further decrements are not seen in Phase II (Fig. S3E). These analyses suggest that RYK, similar to WNT5A, is important for midgut elongation before and throughout Phase I but not during Phase II.

Fig. 3.

RYK is required for midgut elongation throughout Phase I. (A-E′) RNAscope of Ryk on sections of wild-type midguts at E10.5-E14.5. (A′-E′) Higher magnifications of A-E. The epithelial-mesenchymal interface is outlined by white dashed lines. Epi, epithelium; Mes, mesenchyme. Scale bars: 20 µm. (F-Q) Embryos and GI tracts of the wild-type (F,H,J,L,N,P) and Ryk null (G,I,K,M,O,Q) at E10.5, E12.5 and E14.5. Scale bars: 1 mm. (R) Quantitation of midgut length and embryo length of Ryk+/+ (black), Ryk+/− (gray) and Ryk−/− (brown) at E12.5 and E14.5. At E12.5, Ryk+/+, n=3; Ryk+/−, n=5; Ryk−/−, n=3. At E14.5, Ryk+/+, n=8; Ryk+/−, n=14, Ryk−/−, n=5. (S) Dynamics of midgut lengthening in Ryk+/+ (black), Ryk+/− (gray) and Ryk−/− (brown) embryos from E10.5 to E14.5. Ryk+/+: n=5 (E10.5), n=4 (E11.5), n=3 (E12.5), n=7 (E13.5), n=8 (E14.5); Ryk+/−: n=7 (E10.5), n=6 (E11.5), n=5 (E12.5), n=12 (E13.5), n=15 (E14.5); Ryk−/−: n=3 (E10.5), n=3 (E11.5), n=3 (E12.5), n=5 (E13.5), n=5 (E14.5). (T-W′) Immunostaining for Ki67 (T-U′) and pHH3 (V-W′) on cross-sections of the central Ryk+/+ and Ryk−/− midgut at E14.5. (T′,U′,V′,W′) Higher magnification of boxed areas in T,U,V,W, respectively. Scale bars: 20 µm. (X) Quantitation of mitosis rate (% pHH3 cells) in the epithelium of control and Ryk−/− midguts. Measurements were performed on 20 sections of five control samples and 16 sections of four Ryk−/− samples at E10.5; 30 sections of three control samples and three Ryk−/− samples at E12.5; 40 sections of five control samples and five Ryk−/− samples at E14.5. Data are mean±s.e.m. Analyses were performed using unpaired nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney test). *P<0.05, **P<0.01; n.s., not significant.

Though the data above show that epithelial ROR2 is dispensable for gut lengthening, it remains possible that RYK and ROR2 play a redundant role in the epithelium, with the presence of RYK compensating when epithelial ROR2 is lost. Therefore, we further depleted Ror2 (after E10.5) in the Ryk−/− background. However, no additional reduction in midgut length was seen in Ryk/Ror2 double knockouts (Fig. S3F), further confirming that RYK plays a major role in gut lengthening, while epithelial ROR2 is not essential for midgut elongation.

As we have previously shown that active proliferation is the major driver for Phase I midgut epithelial tube elongation, we examined the proliferation marker Ki67 (Fig. 3T,U′) and the mitosis marker pHH3 (Fig. 3V,W′) in control and Ryk−/− midgut epithelium. However, no significant differences were found (Fig. 3X), suggesting that the slower elongation of Ryk−/− midguts was not caused by compromised cell division.

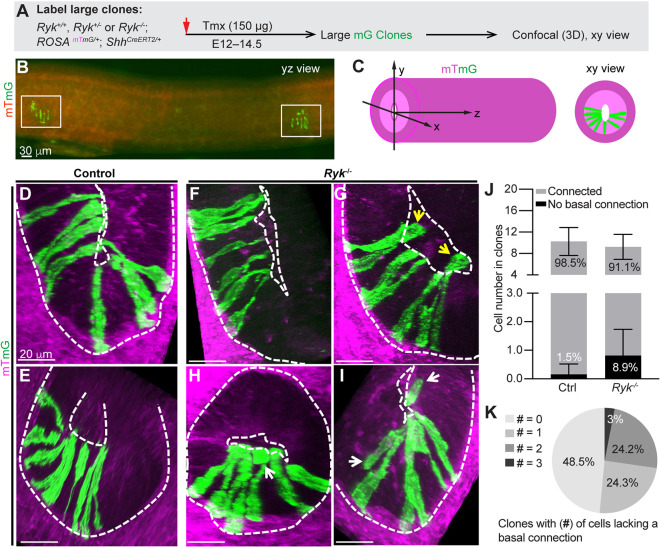

RYK is essential for the proper basal connection of epithelial cells during Phase I midgut elongation

To examine how RYK facilitates midgut elongation at the cellular level, we labeled cell clones in Phase I midgut epithelial tube, using the inducible ShhCreERT2 driver and mTmG reporter system. A very low dose of tamoxifen was given to pregnant dams at E12 to activate membrane eGFP (mG) expression in singly dispersed cells in the midgut epithelium, which then went on to divide and form well-separated large clones at E14.5 (Fig. 4A-C). In control (Ryk+/+ and Ryk+/−) clones, all mG cells touched the apical surface and nearly all were connected to the basal surface, except for a few nascent, post-mitotic cells (1.5%, seven out of 460 cells in 45 clones) (Fig. 4D,E,J). In Ryk−/− midguts, 48.5% of clones appeared normal, with all mG cells connected to both apical and basal surfaces (Fig. 4F,K). However, the remaining clones contained one to three cells lacking a basal connection; some of these cells were even displaced into the lumen (Fig. 4G-I,K). In total, 8.9% (27 out of 305) of all mG cells in Ryk−/− clones were unconnected to the basal surface (Fig. 4J), suggesting that RYK is required for efficient basal connection. Of note, these clonal defects were very similar to those seen in large clones in Wnt5a−/− midguts (Wang et al., 2018).

Fig. 4.

RYK is essential for the proper basal connection of epithelial cells during Phase I midgut elongation. (A) Experimental approach for labeling large epithelial mG clones in control and Ryk−/− midgut for 3D confocal imaging. (B) 2D lateral (yz) view of a segment of midgut containing two separate, large clones (white boxes). Scale bar: 30 µm. (C) Definition of xyz dimensions of the midgut tube. (D-I) 3D confocal z-stacks (xy view) of large clones in control (D,E) and Ryk−/− (F-I) midguts. Apical and basal surfaces are outlined by white dashed lines. White arrows indicate cells lacking a basal connection in the epithelium; yellow arrows indicate epithelial cells in the lumen. Scale bars: 20 µm. (J) Quantitation of the number of cells with or without a basal connection in control and Ryk−/− large clones. Control, 45 clones from six midguts; Ryk−/−, 33 clones from five midguts. Data are mean±s.e.m. (K) Distribution of clones containing 0, 1, 2 or 3 cells that are unconnected to the basal surface. Thirty-three clones from five Ryk−/− midguts were analyzed.

Some RYK-deficient ‘pathfinding’ daughter cells fail to grow a basally directed filopodial protrusion to make a basal connection

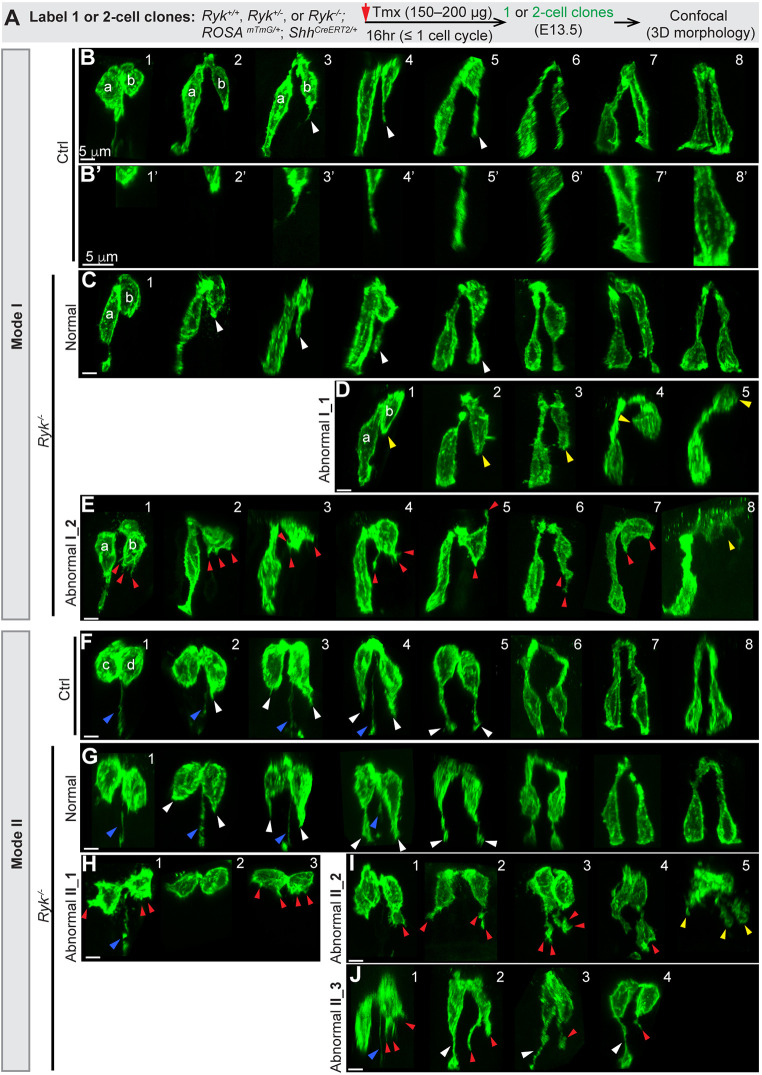

To further characterize how some epithelial cells fail to properly connect basally, we captured the 3D morphology of individual epithelial cells at different phases of the cell cycle by generating one- or two-cell clones in control and Ryk−/− midguts (Fig. 5A). Captured cells were arranged in an order based on their nuclear position. Consistent with our previous report (Wang et al., 2018), as the nucleus moves apically for mitosis (Fig. S4A,B-E′), the cell maintains its basal connection, which gradually turns into a thin basal process. This basal process splits in two during mitosis (Fig. S4A,F-G′); later, one of the two processes retracts in most cases (Fig. S4A,H,H′). During cytokinesis, only one of two daughter cells inherits this basal process, while the other is born without a basal connection (Fig. 5B1,C1,F1,G1,H1). No obvious differences in cell behaviors before cytokinesis were seen between the control and Ryk−/− mutants.

Fig. 5.

In the absence of RYK, some ‘pathfinding’ daughter cells fail to grow a basally directed filopodial protrusion to make a basal connection. (A) Strategy for generating one- or two-cell clones in control and Ryk−/− midgut epithelial tubes at E13.5 for confocal imaging. (B-E) 3D reconstructions of Mode I daughter pairs in control (B,B′) and Ryk−/− (C-E) midguts. Normal basally oriented filopodial protrusions (B,C) are indicated by white arrowheads. B′ shows higher magnifications of the bottom regions of pathfinding cells shown in B: the basal tip of recently divided cells (1′,2′); early filopodial projection (3′,4′); filopodial thickening and basal connection (5′-8′). In D, cells with no filopodial protrusion are indicated by yellow arrowheads. In E, abnormal protrusions are indicated by red arrowheads; the yellow arrowhead in E8 indicates a pre-apoptotic cell. Scale bars: 5 µm. (F-J) 3D reconstructions of Mode II pairs in control (F) and Ryk−/− (G-J) midguts. Normal basally oriented filopodial protrusions are indicated by white arrowheads in F,G,J; abnormal protrusions are indicated by red arrowheads in H-J; the inherited basal processes are indicated by blue arrowheads in F-H,J. The yellow arrowheads in I5 indicate a fragmented cell. Scale bars: 5 µm.

After cytokinesis, the two daughter cells begin to return their nuclei basally via one of two modes. In control Mode I (Fig. 5B), one daughter cell (a) directly uses its inherited basal process to transport the nucleus back – the ‘conduit’ strategy – whereas its sister (b) takes a ‘pathfinding’ strategy. The pathfinding daughter (b) first elongates and adopts a pyriform shape (Fig. 5B1,2). Often, before the nucleus of daughter (a) reaches the basal side, daughter (b) has assembled a very fine filopodium (diameter<0.6 µm, Fig. 5B3,3′) at its most basal tip. This nascent filopodium quickly extends basally and slowly increases in girth (0.5-1.6 µm in diameter), becoming a single thick filopodial protrusion (Fig. 5B4,4′). It finally reaches the basal lamina, establishing a path (13-24 µm long) (Fig. 5B5,5′) for the nucleus of daughter (b) to exit the apical zone. In control Mode II (Fig. 5F), one daughter cell possesses a basal process (Fig. 5F1-4) but does not use it as a nuclear return path; rather both daughters (c) and (d) take the ‘pathfinding’ approach and grow a new filopodium (white arrowheads in Fig. 5F2-4) for nuclear return. Interestingly, the unutilized basal process (blue arrowheads in Fig. 5F1-4) persists only in pairs in which neither daughter's filopodial protrusions have yet reached the basal surface, suggesting that the basal process serves as a tether while both daughters are exploring their path, but quickly disappears once one or both daughters successfully establish a de novo basal connection (Fig. 5F5).

In Ryk−/− midgut epithelium, most daughter pairs (>80%) appear normal in both Mode I (Fig. 5C) and Mode II (Fig. 5G). However, abnormal pairs with a range of defects are also seen (Fig. 5D,E,H-J). Abnormal Mode I pairs are divided into two groups. In the first group (Abnormal I_1, Fig. 5D), pathfinding daughter (b) fails to grow a basal filopodial protrusion, even after the nucleus of daughter (a) has reached the basal side (Fig. 5D3). Some daughters (b) project apically rather than basally (Fig. 5D4) or exit the epithelial layer (Fig. 5D5). In the second group (Abnormal I_2, Fig. 5E), daughter (b) extends multiple short protrusions (<3 µm) (Fig. 5E1-3,5,7) or a branched filopodium (Fig. 5E4,6); its nucleus stays at the apical side of the epithelium (Fig. 5E1-5,7) or moves to the lumen (Fig. 5E8). In both groups, the ‘conduit’ daughter (a) seems unaffected.

Abnormal Mode II pairs are divided into three groups. In the first group (Abnormal II_1, Fig. 5H), both daughters retain a relatively round shape with no protrusion (Fig. 5H2) or multiple tiny protrusions (red arrowheads, Fig. 5H1,3). In the second group (Abnormal II_2, Fig. 5I), two daughters make an oddly shaped extension (red arrowhead) that approaches the basal side. In the third group (Abnormal II_3, Fig. 5J), one daughter appears normal or successfully makes a basal connection (white arrowhead), while the other daughter sends a bifurcated (Fig. 5J2), trifurcated (Fig. 5J1), twisted (Fig. 5J3) or truncated protrusion (Fig. 5J4) (red arrowheads), suggesting that two ‘pathfinding’ daughters from the same mother do not always encounter errors simultaneously without RYK. Of note, although some pathfinding cells fail to properly project basally, they still stay apically connected to their sisters.

RYK facilitates efficient basal tethering of ‘pathfinding’ cells, which is essential for a timely nuclear return

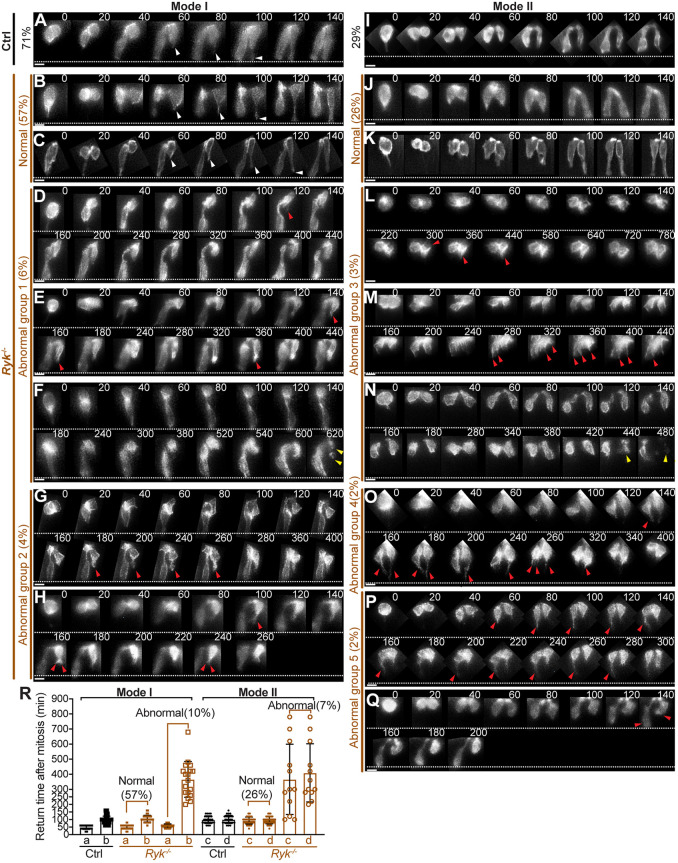

All of the above observations were based on a detailed comparison of the shapes of individual static cells within fixed midguts between controls and Ryk−/− mutants. Considering that filopodial pathfinding is highly dynamic, the behaviors and consequences of those abnormally shaped cells were unclear. To address this, we turned to 2D live imaging of cultured gut explants. However, as the active gut peristaltic movements and the culture setting imposed a resolution limit, the time-lapse images were at a lower resolution. Consistent with our previous report (Wang et al., 2018), daughter pairs in control midguts return in either Mode I or II. Mode I pairs (71%, 65 out of 91 pairs observed) return the ‘conduit’ nucleus quickly (average 48 min) and the ‘pathfinding’ nucleus slowly (average 101 min) (Fig. 6A,R). In Mode II, the nuclei of both daughters return at a similar speed (∼100 min) (Fig. 6I,R).

Fig. 6.

RYK facilitates efficient basal tethering of ‘pathfinding’ cells, which is essential for a timely nuclear return. (A-Q) Live imaging of the basal return of Mode I (A-H) and Mode II pairs (I-Q) in control (A,I) and Ryk−/− midguts (B-H; J-Q). Sequential 2D images taken at labeled time points (minutes) are displayed; time 0 marks the mitosis. White arrowheads indicate normal filopodial protrusions; red arrowheads indicate abnormal protrusions; yellow arrowheads indicate apoptotic cells. White dotted lines mark the basal surface. Scale bars: 10 µm. (R) Quantitation of nuclear return time for Mode I daughter a and b, and Mode II daughter c and d in control (black) and Ryk−/− (brown) midguts. Solid squares and circles reflect the actual returning time. Open squares and circles reflect the time that nuclei stay at the apical side during the recording. Ninety-one daughter pairs from five control midguts and 176 pairs from six Ryk−/− midguts were analyzed. Data are mean±s.e.m.

In Ryk−/− midguts, most daughter pairs (83%, 146 out of 176 observed) appear normal in both Mode I (Fig. 6B,C) and Mode II (Fig. 6J,K); Mode I was still more prevalent (100 out of 146). However, some pairs (17%, 30 out of 176) were clearly aberrant in either Mode I (10%) or Mode II (7%). In abnormal Mode I pairs, ‘conduit’ daughters returned on time (40-80 min, average 58 min), but ‘pathfinding’ daughters all failed to return during the recording (Fig. 6D-H,R). The abnormal Mode I pairs can be further characterized into two groups. In group 1 (6%, Fig. 6D-F), ‘pathfinding’ daughters either only grew tiny, short-lived projections (length<2 µm, indicated by red arrowheads in Fig. 6D,E) or had no visible projections (Fig. 6F). In group 2 (4%, Fig. 6G,H), pathfinding daughter cells formed an obvious protrusion (4-15 µm) but this protrusion ceased to grow further to reach the basal lamina (Fig. 6G,H). Some protrusions were bifurcated, the tips of which pointed in different directions, and were later retracted (Fig. 6H).

Three groups of abnormal Mode II pairs (7%, 12 out of 176) were seen (groups 3-5). In group 3 (3%, Fig. 6L-N), both daughter cells actively extended multiple short-lived, tiny spikes (length<2 µm, Fig. 6L,M), corresponding to the 3D cell shape in Fig. 5H3, or no projections (Fig. 6N), corresponding to Fig. 5H2. In group 4 (2%, Fig. 6O), both daughter cells formed a long basal protrusion, which appeared unstable and retracted later, corresponding to cell shapes in Fig. 5I. In group 5 (2%, Fig. 6P,Q), the two sisters in the same pair behaved differently. One daughter grew a long protrusion temporarily whereas the other did not (Fig. 6P). In another pair, one daughter successfully returned but the other projected apically and failed to return (Fig. 6Q). Additionally, with longer recording times, we observed that those pathfinding daughters that fail to return in time eventually fragmented, a sign of apoptosis, in both Mode I and II (yellow arrowhead in Fig. 6F,N), corresponding to cell shapes in Figs Fig. 5E8 and 5I5. Together with quantitative analyses of nuclear return time (Fig. 6R), we conclude that Ryk depletion perturbs the ‘pathfinding’ return, but not the ‘conduit’ return. Although defective pathfinding daughters showed various dynamics, they all failed to extend a stable filopodial protrusion to the basal surface to form a path for nuclear return. These defects closely mimic those aberrant pathfinding cells reported in Wnt5a−/− midguts (Wang et al., 2018).

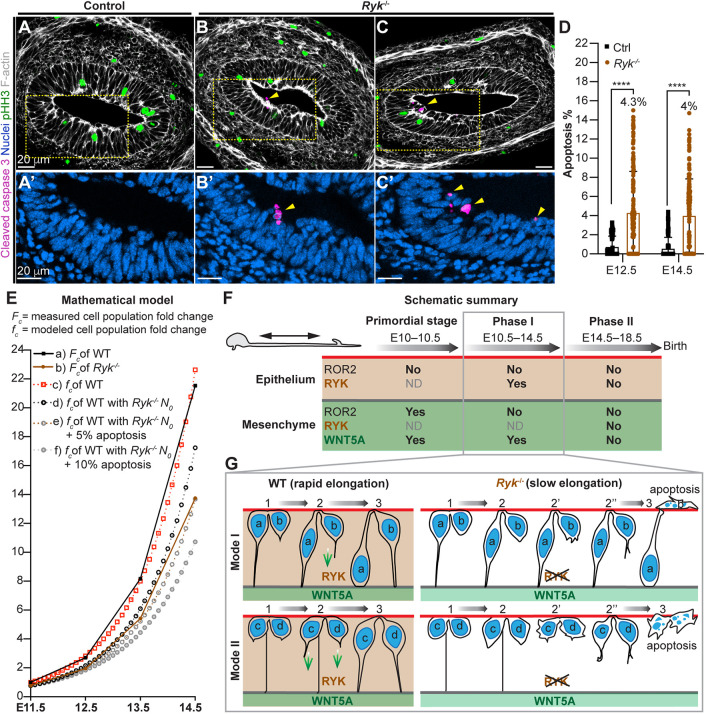

Increased apoptosis contributes to the length deficit of the Ryk−/− midgut epithelial tube

Cell proliferation is unperturbed in the Ryk−/− midgut epithelium (Fig. 3T-X) and live imaging indicates that failure of the pathfinding process cell leads to apoptosis (Fig. 6F,N), but can the rate of apoptosis alone account for the length deficit seen? To address this, we examined cleaved-caspase 3 staining. Apoptotic fragments were readily observed accumulated at the apical side of the Ryk−/− midgut epithelium (Fig. 7B-C′) but not of the control (Fig. 7A,A′). Indeed, the apoptosis rate was significantly increased to 4.4±4% in the Ryk−/− midgut epithelium, compared with 0.5%±1% in controls at E14.5; a similar increase was also observed at E12.5 (Fig. 7D). Next, we used a previously published mathematical model (Wang et al., 2018) to estimate the net fold change of the epithelial cell population over time (E11.5-E14.5) (Fig. 7E). This proliferation-based growth curve (c) aligns well with the measured wild-type cell population growth curve (a) acquired during this time. As Ryk−/− epithelial proliferation was not affected, we modeled idealized cell population growth, extrapolating from the measured Ryk−/− cell population at E11.5 (d), and applied 5% (e) and 10% (f) apoptosis, respectively to predict growth curves. The application of 5% apoptosis in the model closely mirrored the Ryk−/− experimental growth curve (b). Indeed, ∼4% apoptosis was measured in Ryk−/− midguts (Fig. 7D). Together, these data suggest that the diminished elongation of the Ryk−/− midgut results primarily from augmented apoptosis, secondary to impaired filopodial pathfinding and inability to establish a basal connection.

Fig. 7.

Increased apoptosis contributes to the length deficit of the Ryk−/− midgut epithelial tube. (A-C′) Immunostaining of cleaved caspase 3 (magenta), pHH3 (green), F-actin (white) and nuclei (blue) on cross-sections of control (A,A′) and Ryk−/− (B-C′) midguts at E14.5. (A′,B′,C′) Higher magnifications of boxed regions. Scale bars: 20 µm. (D) Quantitation of apoptotic ratio (cleaved caspase 3 fragment number/total epithelial cell number) on cross-sections of control and Ryk−/− midguts. Analyses were performed on 55 sections of five control samples and 125 sections of five Ryk−/− samples at E12.5, 110 sections of five control samples and 140 sections of seven Ryk−/− samples at E14.5. Data are mean±s.e.m. Analyses were performed using unpaired nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney test), ****P<0.0001. (E) Mathematical model (see details in Materials and Methods). Solid lines reflect the fold changes in wild-type (a, black) and Ryk−/− (b, brown) epithelial cell population based on experimental measurements (Fc); dotted lines (c-f) reflect the fold changes in epithelial cell population based on mathematical modeling (fc). (c) The idealized growth curve, with a starting cell population (N0) that equals the wild-type cell population at E11.5; (d) the idealized growth curve with N0 adjusted to the Ryk−/− cell population at E11.5. Gray dotted lines are modeled growth curves after introducing 5% (e) or 10% (f) apoptosis to (d). (F) Summary of when and where WNT5A, ROR2 and RYK contribute to midgut elongation. The fetal SI elongation can be divided into three stages: primordial stage, Phase I and Phase II. WNT5A is expressed in the midgut mesenchyme, while the WNT5A receptors ROR2 and RYK are expressed in both epithelium and mesenchyme. WNT5A and RYK are required for midgut elongation before and during Phase I. In contrast, ROR2 acts in the mesenchymal compartment to drive midgut elongation only in the primordial stage. ND, not determined. (G) Schematic illustration of pathfinding defects in Ryk−/− midgut epithelium. During Phase I, without RYK, some pathfinding cells (b, c, d) do not grow filopodia (2), form short protrusions in a random direction (2′) or odd-shaped protrusions (2″). These cells eventually fail to make a basal connection, leading to increased apoptosis and a shortened gut.

DISCUSSION

Dynamic spatial and temporal roles for WNT5A, ROR2 and RYK in midgut elongation

Our findings provide a deeper understanding of how WNT5A signaling temporally and spatially regulates midgut lengthening by engaging different receptors (Fig. 7F). Previous studies, based on global knockouts of Ror2 (Yamada et al., 2010) and Wnt5a (Cervantes et al., 2009), suggested that a WNT5A-ROR2 axis is important in regulating convergence-extension cellular movements within the epithelium that drive gut lengthening. However, the epithelial-specific Ror2 deletion data presented here demonstrate that epithelial ROR2 is dispensable for midgut elongation. Rather, mesenchymal ROR2 is required.

Like ROR2, RYK is expressed in both midgut epithelium and mesenchyme. In Ryk−/− midguts, however, clear phenotypes are limited to the epithelial compartment and consist of defective filopodial protrusions by post-mitotic epithelial cells. Though experiments with constitutive Ryk knockout mice alone cannot definitively exclude an additional role for mesenchymal RYK signaling related to midgut elongation, no apparent defects nor increases in apoptosis were noted in the Ryk−/− mesenchymal compartment. Moreover, mathematical modeling establishes that the level of apoptosis measured experimentally in the epithelium can fully account for the observed differences in the elongation rate of Ryk−/− midgut epithelial tubes. Given that RYK is well documented to act in a cell-autonomous manner (Hing et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2019; Roy et al., 2018; Tourette et al., 2014; Zhong et al., 2011), these data together strongly suggest that RYK function is crucial in the epithelium during Phase I midgut elongation.

In addition to acting in distinct sites (epithelial versus mesenchymal), ROR2 and RYK also act in different temporal windows to control gut lengthening (Fig. 7F). ROR2 acts in the mesenchyme prior to E10.5, suggesting that a mesenchymal WNT5A-ROR2 autocrine signaling may mediate the primordial midgut elongation, though mechanistic details await further investigation. After E10.5, the global loss of Ror2 has very little effect on midgut elongation. In contrast, the length deficit of Wnt5a−/−and Ryk−/− midguts increases during Phase I, indicating that both WNT5A and RYK participate throughout the entire Phase I elongation in a WNT5A-RYK paracrine fashion. In Phase II (E14.5 to birth), when the midgut epithelium undergoes expansion initiated by villus formation, WNT5A, RYK and ROR2 do not appear to participate significantly in further elongation. The dynamic spatiotemporal requirement for distinct WNT5A receptors, as illustrated here, indicates that fetal gut elongation occurs through precise coordination of signals in both epithelial and mesenchymal compartments in a phased manner.

RYK mediates filopodial pathfinding in response to an attractant WNT5A cue during Phase I midgut elongation

The loss of Ryk causes epithelial phenotypes (Fig. 7G) that closely mimic those seen in the Wnt5a−/− midgut during Phase I. First, both mutants exhibit identical filopodial navigation errors in three categories: pathfinding daughter cells fail to extend a filopodium, send multiple short protrusions in a random direction or generate an unstable filopodial protrusion (characterized by branching, twisting or adopting other odd shapes) (Fig. 7G). Second, although pathfinding defects are seen, conduit nuclear return is normal. Additionally, cellular behaviors before G1 Phase, including apical nuclear migration, basal process splitting and cytokinesis, are unaffected. Third, in both mutants, failure of basal re-tethering results in the accumulation of apoptotic cells at the apical side of the epithelium. These data together suggest that RYK mediates WNT5A signaling to control directional filopodial growth in the pseudostratified midgut epithelium.

Still, compared with Wnt5a−/− mutants, a smaller population of epithelial cells lack a basal connection in Ryk−/− midguts (13% in Wnt5a−/− versus 8.9% in Ryk−/− large clones), suggesting that RYK is not the only WNT5A receptor to facilitate filopodial pathfinding. We ruled out ROR2 because the loss of epithelial ROR2 causes no defects in gut length. However, another ROR member, ROR1, is also expressed in the gut (Al-Shawi et al., 2001). Ror1−/− mice are viable and appear normal at birth, but Ror1/2 double deletion results in severe defects that phenocopy Wnt5a−/− mutants, suggesting some redundancy between ROR1 and ROR2 in mediating WNT5A signaling (Ho et al., 2012). This raises the possibility that ROR1 and ROR2 work together to transduce WNT5A cue for pathfinding cells. Alternatively, FZD5 is another candidate. It is highly expressed in early mouse midgut (Liu et al., 2008), and it can bind and respond to WNT5A by internalization from the cell surface (Kurayoshi et al., 2007). On the flip side, several other WNTs can also bind and signal through RYK, including canonical WNT1 and WNT3A (Lu et al., 2004), and non-canonical WNT5B (Lin et al., 2010), but none of these WNTs is present in Phase I midgut (Lickert et al., 2001). Thus, WNT5A is probably the primary cue for RYK in this context. Importantly, however, many pathfinding daughters still project their protrusions correctly and directionally without WNT5A or RYK, suggesting the existence of additional unrecognized guidance cues.

Interestingly, WNT5A, which is transduced by RYK, was previously identified as a repulsive cue in both murine corticospinal tract axon pathfinding (Keeble et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2005) and in Drosophila midline axon crossing (Yoshikawa et al., 2003). However, in the midgut epithelium, filopodial protrusions grow towards the source of WNT5A, indicating that WNT5A acts as an attractant. Therefore, WNT5A-RYK can function as either attractant or repellent, depending on the tissue context or responding cell types.

The pathways acting downstream of WNT5A-RYK to promote directional filopodial growth remain unclear. RYK is an atypical RTK receptor that lacks kinase activity (Hovens et al., 1992). It acts more like a scaffold, promoting the binding of other receptors or intracellular proteins (Roy et al., 2018). With this in mind, three possible targets can be entertained. The first candidate is VANGL2. Biochemical data suggest that WNT5A can promote RYK binding to VANGL2, leading to increased VANGL2 stability (Andre et al., 2012). VANGL2 is enriched at tips of filopodia in neurons (Davey et al., 2016; Dos-Santos Carvalho et al., 2020; Shafer et al., 2011) and can regulate filopodial dynamics (Davey et al., 2016; Dos-Santos Carvalho et al., 2020), possibly by modulating the engagement of N-cadherin with the actin cytoskeleton flow (Dos-Santos Carvalho et al., 2020). The second one is c-SRC, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase. The PDZ-binding domain of RYK can promote the binding and activation of intracellular c-SRC (Petrova et al., 2013; Wouda et al., 2008). Local c-SRC kinase activity promotes filopodial initiation and extension at the tips of growth cones (Robles et al., 2005). Additionally, RYK regulates axon outgrowth by activating Ca2+ signaling in a WNT5A-dependent manner (Li et al., 2009). Future exploration of these possibilities in the context of midgut is needed.

Implications for congenital short bowel syndrome (CSBS)

During Phase I, nearly all epithelial cells undergo continuous cell cycling, leading to an exponential growth of the cell population and rapid gut lengthening. Losing a small proportion of cells in Phase I caused by impaired pathfinding can have a robust effect on overall SI length, as seen in shortened Ryk−/− and Wnt5a−/− SIs at birth, and as further confirmed by mathematical modeling. In this vein, it is noteworthy that mutations in FLNA have been identified as the cause of an X-linked CSBS (Gargiulo et al., 2007) but the mechanism remains unclear. FLNA is an actin-binding protein and can modulate filopodial formation (Chiang et al., 2017; Nishita et al., 2006; Ohta et al., 1999). In melanoma cells, WNT5A can remodel the cytoskeleton by promoting cleavage of FLNA through Ca2+-dependent signaling (O'connell et al., 2009). Although it has not been tested to our knowledge, a potential interaction between RYK and FLNA could unite WNT5A/RYK-mediated filopodial dynamics with the pathogenesis of FLNA-related CSBS in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental model and subject details

Mice and embryo staging

All mouse work was performed in accordance with guidelines from the University of Michigan's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and University Laboratory Animal Medicine as well as Duke University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mouse strains in this study were: C57BL6/J (Charles River), Ryk+/− from Dr Steven Stacker at Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute (Halford et al., 2000), Ror2fl/fl (JAX 018354) (Ho et al., 2012), ROSAmTmG/+ (JAX 007576) (Muzumdar et al., 2007), ShhCreERT2/+ (JAX 005623) (Harfe et al., 2004), ShhCre/+ (JAX 005622) (Harfe et al., 2004), Twist2Cre/+ (JAX 008712) (Sosic et al., 2003) and UbcCreERT2/+ (JAX 007001) (Ruzankina et al., 2007). Mice (6 weeks to 8 months old) were maintained in facilities with 12 h light/dark cycles. Both males and females were analyzed. Stage-specific embryos were isolated from timed matings based on the observation of a copulatory plug, which represents E0.5. E14.5 and younger embryos were also staged precisely using the staging system of Theiler (1989).

Method details

Genotyping

Genotyping PCRs were performed using GoTaq Flexi PCR kit (Promega M8295) and Taq DNA Polymerase, native kit (Invitrogen 18038). Primers were made from Integrated DNA Technologies. PCR primer sequences and protocols were as listed on the Jackson Laboratory website and in Table S1.

Tamoxifen preparation and administration

Tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648) powder (200 mg) was dissolved into 10 ml fresh corn oil (Sigma, C8267) to make the 20 mg/ml tamoxifen stock. The stock was further diluted into corn oil for a total volume of 200 μl for each gavage. For Ror2 depletion with UbcCreERT2, pregnant females were gavaged with 2 mg tamoxifen at E9 and 2 mg tamoxifen at E10.5, or 2 mg at E10.5 and 2 mg at E11.5. For labeling large clones in midgut epithelial tube, pregnant females were gavaged with 150 μg tamoxifen at E12, and embryos were harvested at E14.5. For labeling 1- or 2-cell clones, pregnant females were gavaged with 150-200 μg tamoxifen 16 h before harvesting at E13.5.

Midgut fixation and immunostaining

Dissected midguts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. For paraffin sectioning, fixed midguts were embedded into histogel (Thermo Scientific HG-4000-012). Histogel blocks were then dehydrated in ethanol, infused with paraffin, embedded in paraffin blocks and sectioned at 5 μm (Wang et al., 2013). Before staining, sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated, washed with PBS and then boiled in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6) for 10 min for antigen retrieval. During staining, sections were blocked with 4% goat serum, 0.1% TritonX-100 in PBS for 30 min, then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, rinsed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature (for antibody details, see Table S1). For cryosectioning, fixed midguts were directly embedded into optimal cutting temperature (OCT). OCT blocks were frozen on dry ice and sectioned at 5 μm. The staining protocol was the same as for the paraffin section staining. The stained samples were mounted with Prolong Gold (Life Technologies P36930) and imaged by an Axio Imager, apotome microscope, using 20× NA 0.8 plan-apochromat or 40× NA 1.3 oil EC Plan-Neofluar objective and recommended settings in Zeiss Zen blue software.

3D cell morphology imaging

Dissected midguts were fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature and rinsed with PBS. Fixed midguts were aligned on glass slides, immersed in Focus Clear solution (Cedarlane Labs) for 30 min until transparent, and then mounted with Mount Clear solution (Cedarlane Labs). Imaging was performed using a Nikon A-1 confocal microscope or Zeiss 880 inverted confocal microscope using a 40× oil objective (Nikon Plan Fluor 40× NA 1.3 or Zeiss 40× NA 1.3 oil EC Plan-Neofluar) and 488 and 561 nm laser for excitation with pinhole set for 1 Airy unit for red emission range. Z-stacks were acquired and then 3D reconstructed using Imaris software (Bitplane).

2D live imaging of midgut

After removal from embryos, midguts were immediately placed on the top of a clear transwell filter in a glass-bottom Petri dish filled with 1 ml culture medium (10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine in DMEM), as previously described (Costantini et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2018). This culture dish was then incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 h to allow midguts to attach to the transwell membrane. Time-lapse imaging was performed on a DeltaVision image restoration microscopy system using a 10×/0.40 UPlanSApo dry or 20×/0.75 UPlanSApo dry objective, Photometrics CoolSnap HQ camera, InsightSSI 7 channel solid-state illumination source, and GFP filter set (475/28ex and 525/50em). The imaging data were deconvolved by SoftWoRx software deconvolution algorithm constrained iterative method and analyzed with Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

RNAscope in situ hybridization

Dissected midguts were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight at room temperature and washed with DNAse/RNAse free water (Gibco) for three changes for a total of 2 h. Tissues were then processed for paraffin sectioning as described above. The in situ hybridization assay was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (ACD: RNAscope 2.5 HD Detection Reagent–BROWN User Manual). Both Ror2 and Ryk probes were generated by ACD and are commercially available (Ror2, 430041; Ryk, 549981). The Ror2 probe targets nucleotides 2204-3125 of mouse Ror2 mRNA (accession number NM_013846.3); the Ryk probe targets nucleotides 301-1433 of mouse Ryk mRNA (accession number NM_013649.3).

Mathematical modeling

Modeling parameters have been described previously (Wang et al., 2018). Briefly, the fold change in the measured epithelial cell population was determined as Fc, Fc=FxyFZ. Fxy, where Fxy is the measured fold change in actual epithelial cell number on the xy plane (nuclei number on cross-sections), while FZ is the measured fold change in cell number along the z-axis, which can be simplified as the measured fold change in length Fl, assuming a negligible change in cell width and volume over time. In the mathematical model, the growth of the epithelial cell population is driven by symmetrical divisions in a uniform population of progenitor cells. As each cell divides every 16 h (Wang et al., 2018), the cell population at the next cycle, Nt+1, will exhibit geometrical growth: Nt+1=kNt, where k is the net cell population fold change. The modeled fold change is fc, fc=Nt/N0. Without apoptosis, 100 cells become 200 cells at the end of one cell cycle, k=2. When 5% apoptosis occurs, five out of 100 cells are lost and only 95 cells divide, resulting in 190 cells after one cell cycle. Mathematically, the model with apoptosis becomes Nt+1=k(1−a)Nt, where a is the apoptosis rate.

Image analysis

Measurements of the midgut and embryo length were performed on GI or embryo images (from at least three independent littermates) using Fiji/ImageJ. Measurements and quantitation of midgut epithelial tube circumferences, epithelial height, nuclei number, mitosis rate and apoptotic rate were also performed on stained sections (from at least three separate midgut specimens) using Fiji/ImageJ. The clonal size, number of cells with or without a basal connection, and number of clones with 0, 1, 2 or 3 basally unattached cells were counted on 3D reconstructed images using Imaris (from at least three independent experiments). Quantitation of returning time for Mode I and II pairs (from at least three independent experiments) was performed on time-lapse images using Fiji/ImageJ.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and graphs were generated in Excel or GraphPad Prism 6. All quantifications were collected from at least three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons of data between groups (e.g. control versus experimental condition) were made using unpaired nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney test). P<0.05 was considered significant. Data are represented as mean or mean±s.e.m. On graphs, P-values were reported as follows: * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001; n.s., not significant.

Image processing

In Fig. 3F-I, a black rectangle was placed behind each image as the background. In Fig. 5B-D, separate images were adjusted to the same scale, cropped, rotated and combined into one panel. One black rectangle is placed behind each panel as the background. In Fig. 6A-Q, images at different time points of live imaging were adjusted to the same scale, cropped, rotated and combined into one panel. One black rectangle is placed behind each panel as the background.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Brigid Hogan, Blanche Capel and Kwabena Badu-Nkansah for editing the manuscript; Drs Daniel Lucas and Yuji Mishina for sharing their UbcCreERT2/+ mouse; Dr Kaitlin Basham from Dr Gary Hammer's laboratory and Sha Huang from Dr Jason Spence's laboratory for sharing reagents; Dr Santiago Schnell for mathematical modeling; Ryan Townshend for RT-PCR guidance; Dr Honglai Zhang for RYK western blot; Dr Matt Kofron at CCHMC; Dr Aaron Taylor at the Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory at the University of Michigan; and Drs Benjamin Carlson and Yasheng Gao at the Duke Light Microscopy Core Facility for imaging assistance.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.W., D.L.G., T.L.; Methodology: S.W., Y.-H.T., L.C., K.W.; Validation: S.W.; Formal analysis: S.W., A.J.T.; Investigation: S.W., J.P.R., A.J.T., E.B.W., J.U.; Resources: D.L.G., T.L., S.A.S., J.R.S.; Data curation: S.W.; Writing - original draft: S.W.; Writing - review & editing: D.L.G., T.L., S.W., J.P.R., S.A.S.; Visualization: S.W.; Supervision: S.W., D.L.G., T.L.; Project administration: S.W., D.L.G., T.L.; Funding acquisition: D.L.G., T.L.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK089933 to D.L.G. and R01 DK117981 to T.L.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at https://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.195388.supplemental

Peer review history

The peer review history is available online at https://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.195388.reviewer-comments.pdf

References

- Al-Shawi R., Ashton S. V., Underwood C. and Simons J. P. (2001). Expression of the Ror1 and Ror2 receptor tyrosine kinase genes during mouse development. Dev. Genes Evol. 211, 161-171. 10.1007/s004270100140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre P., Wang Q., Wang N., Gao B., Schilit A., Halford M. M., Stacker S. A., Zhang X. and Yang Y. (2012). The Wnt coreceptor Ryk regulates Wnt/planar cell polarity by modulating the degradation of the core planar cell polarity component Vangl2. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 44518-44525. 10.1074/jbc.M112.414441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood M. J. and Mcmahon A. P. (1995). Hedgehog and Bmp Genes Are Coexpressed at Many Diverse Sites of Cell-Cell Interaction in the Mouse Embryo. Dev. Biol. 172, 126-138. 10.1006/dbio.1995.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes S., Yamaguchi T. P. and Hebrok M. (2009). Wnt5a is essential for intestinal elongation in mice. Dev. Biol. 326, 285-294. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang T.-S., Wu H.-F. and Lee F.-S. (2017). ADP-ribosylation factor-like 4C binding to filamin-A modulates filopodium formation and cell migration. Mol. Biol. Cell 28, 3013-3028. 10.1091/mbc.e17-01-0059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini F., Watanabe T., Lu B., Chi X. and Srinivas S. (2011). Dissection of embryonic mouse kidney, culture in vitro, and imaging of the developing organ. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols 2011, pdb-prot5613 10.1101/pdb.prot5613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey C. F., Mathewson A. W. and Moens C. B. (2016). PCP Signaling between Migrating Neurons and their Planar-Polarized Neuroepithelial Environment Controls Filopodial Dynamics and Directional Migration. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005934 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos-Santos Carvalho S., Moreau M. M., Hien Y. E., Garcia M., Aubailly N., Henderson D. J., Studer V., Sans N., Thoumine O. and Montcouquiol M. (2020). Vangl2 acts at the interface between actin and N-cadherin to modulate mammalian neuronal outgrowth. eLife 9 10.7554/elife.51822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freddo A. M., Shoffner S. K., Shao Y., Taniguchi K., Grosse A. S., Guysinger M. N., Wang S., Rudraraju S., Margolis B., Garikipati K. et al. (2016). Coordination of signaling and tissue mechanics during morphogenesis of murine intestinal villi: a role for mitotic cell rounding. Integr. Biol 8, 918-928. 10.1039/c6ib00046k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo A., Auricchio R., Barone M. V., Cotugno G., Reardon W., Milla P. J., Ballabio A., Ciccodicola A. and Auricchio A. (2007). Filamin A is mutated in X-linked chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction with central nervous system involvement. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80, 751-758. 10.1086/513321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J., Nusse R. and van Amerongen R. (2014). The role of Ryk and Ror receptor tyrosine kinases in Wnt signal transduction. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 6 10.1101/cshperspect.a009175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse A. S., Pressprich M. F., Curley L. B., Hamilton K. L., Margolis B., Hildebrand J. D. and Gumucio D. L. (2011). Cell dynamics in fetal intestinal epithelium: implications for intestinal growth and morphogenesis. Development 138, 4423-4432. 10.1242/dev.065789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford M. M., Armes J., Buchert M., Meskenaite V., Grail D., Hibbs M. L., Wilks A. F., Farlie P. G., Newgreen D. F., Hovens C. M. et al. (2000). Ryk-deficient mice exhibit craniofacial defects associated with perturbed Eph receptor crosstalk. Nat. Genet. 25, 414-418. 10.1038/78099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe B. D., Scherz P. J., Nissim S., Tian F., McMahon A. P. and Tabin C. J. (2004). Evidence for an expansion-based temporal Shh gradient in specifying vertebrate digit identities. Cell 118, 517-528. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasosah M., Lemberg D. A., Skarsgard E. and Schreiber R. (2008). Congenital short bowel syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 22, 71-74. 10.1155/2008/590143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing H., Reger N., Snyder J. and Fradkin L. G. (2020). Interplay between axonal Wnt5-Vang and dendritic Wnt5-Drl/Ryk signaling controls glomerular patterning in the Drosophila antennal lobe. PLoS Genet. 16, e1008767 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho H.-Y., Susman M. W., Bikoff J. B., Ryu Y. K., Jonas A. M., Hu L., Kuruvilla R. and Greenberg M. E. (2012). Wnt5a-Ror-Dishevelled signaling constitutes a core developmental pathway that controls tissue morphogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 4044-4051. 10.1073/pnas.1200421109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovens C. M., Stacker S. A., Andres A. C., Harpur A. G., Ziemiecki A. and Wilks A. F. (1992). RYK, a receptor tyrosine kinase-related molecule with unusual kinase domain motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 11818-11822. 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeble T. R., Halford M. M., Seaman C., Kee N., Macheda M., Anderson R. B., Stacker S. A. and Cooper H. M. (2006). The Wnt receptor Ryk is required for Wnt5a-mediated axon guidance on the contralateral side of the corpus callosum. J. Neurosci. 26, 5840-5848. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1175-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi A., Yamamoto H., Sato A. and Matsumoto S. (2012). Wnt5a: its signalling, functions and implication in diseases. Acta Physiol 204, 17-33. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-T., Yin W., Nakamichi Y., Panza P., Grohmann B., Buettner C., Guenther S., Ruppert C., Kobayashi Y., Guenther A. et al. (2019). WNT/RYK signaling restricts goblet cell differentiation during lung development and repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 25697-25706. 10.1073/pnas.1911071116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugathasan K., Halford M. M., Farlie P. G., Bates D., Smith D. P., Zhang Y. F., Roy J. P., Macheda M. L., Zhang D., Wilkinson J. L. et al. (2018). Deficiency of the Wnt receptor Ryk causes multiple cardiac and outflow tract defects. Growth Factors 36, 58-68. 10.1080/08977194.2018.1491848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurayoshi M., Yamamoto H., Izumi S. and Kikuchi A. (2007). Post-translational palmitoylation and glycosylation of Wnt-5a are necessary for its signalling. Biochem. J. 402, 515-523. 10.1042/BJ20061476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Hutchins B. I. and Kalil K. (2009). Wnt5a Induces Simultaneous Cortical Axon Outgrowth and Repulsive Axon Guidance through Distinct Signaling Mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 29, 5873-5883. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0183-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickert H., Kispert A., Kutsch S. and Kemler R. (2001). Expression patterns of Wnt genes in mouse gut development. Mech. Dev. 105, 181-184. 10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00390-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S., Baye L. M., Westfall T. A. and Slusarski D. C. (2010). Wnt5b-Ryk pathway provides directional signals to regulate gastrulation movement. J. Cell Biol. 190, 263-278. 10.1083/jcb.200912128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Shi J., Lu C.-C., Wang Z.-B., Lyuksyutova A. I., Song X.-J. and Zou Y. (2005). Ryk-mediated Wnt repulsion regulates posterior-directed growth of corticospinal tract. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1151-1159. 10.1038/nn1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Wang Y., Smallwood P. M. and Nathans J. (2008). An essential role for Frizzled5 in neuronal survival in the parafascicular nucleus of the thalamus. J. Neurosci. 28, 5641-5653. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1056-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W., Yamamoto V., Ortega B. and Baltimore D. (2004). Mammalian Ryk is a Wnt coreceptor required for stimulation of neurite outgrowth. Cell 119, 97-108. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J., Kim B. M., Rajurkar M., Shivdasani R. A. and McMahon A. P. (2010). Hedgehog signaling controls mesenchymal growth in the developing mammalian digestive tract. Development 137, 1721-1729. 10.1242/dev.044586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata T., Okamoto M., Shinoda T. and Kawaguchi A. (2015). Interkinetic nuclear migration generates and opposes ventricular-zone crowding: insight into tissue mechanics. Front. Cell Neurosci. 8 10.3389/fncel.2014.00473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar M. D., Tasic B., Miyamichi K., Li L. and Luo L. (2007). A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45, 593-605. 10.1002/dvg.20335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishita M., Yoo S. K., Nomachi A., Kani S., Sougawa N., Ohta Y., Takada S., Kikuchi A. and Minami Y. (2006). Filopodia formation mediated by receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2 is required for Wnt5a-induced cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 175, 555-562. 10.1083/jcb.200607127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norden C. (2017). Pseudostratified epithelia - cell biology, diversity and roles in organ formation at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 130, 1859-1863. 10.1242/jcs.192997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'connell M. P., Fiori J. L., Baugher K. M., Indig F. E., French A. D., Camilli T. C., Frank B. P., Earley R., Hoek K. S., Hasskamp J. H. et al. (2009). Wnt5A Activates the Calpain-Mediated Cleavage of Filamin A. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 1782-1789. 10.1038/jid.2008.433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta Y., Suzuki N., Nakamura S., Hartwig J. H. and Stossel T. P. (1999). The small GTPase RalA targets filamin to induce filopodia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 2122-2128. 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi I., Suzuki H., Onishi N., Takada R., Kani S., Ohkawara B., Koshida I., Suzuki K., Yamada G., Schwabe G. C. et al. (2003). The receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2 is involved in non-canonical Wnt5a/JNK signalling pathway. Genes Cells 8, 645-654. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova I. M., Lahaye L. L., Martianez T., de Jong A. W., Malessy M. J., Verhaagen J., Noordermeer J. N. and Fradkin L. G. (2013). Homodimerization of the Wnt receptor DERAILED recruits the Src family kinase SRC64B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 4116-4127. 10.1128/MCB.00169-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles E., Woo S. and Gomez T. M. (2005). Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation at the tips of growth cone filopodia promotes extension. J. Neurosci. 25, 7669-7681. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2680-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J. P., Halford M. M. and Stacker S. A. (2018). The biochemistry, signalling and disease relevance of RYK and other WNT-binding receptor tyrosine kinases. Growth Factors 36, 15-40. 10.1080/08977194.2018.1472089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzankina Y., Pinzon-Guzman C., Asare A., Ong T., Pontano L., Cotsarelis G., Zediak V. P., Velez M., Bhandoola A. and Brown E. J. (2007). Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell Stem Cell 1, 113-126. 10.1016/j.stem.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B. et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676-682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer B., Onishi K., Lo C., Colakoglu G. and Zou Y. (2011). Vangl2 promotes Wnt/planar cell polarity-like signaling by antagonizing Dvl1-mediated feedback inhibition in growth cone guidance. Dev. Cell 20, 177-191. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosic D., Richardson J. A., Yu K., Ornitz D. M. and Olson E. N. (2003). Twist regulates cytokine gene expression through a negative feedback loop that represses NF-kappa B activity. Cell 112, 169-180. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00002-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K., Bachiller D., Chen Y. P., Kamikawa M., Ogi H., Haraguchi R., Ogino Y., Minami Y., Mishina Y., Ahn K. et al. (2003). Regulation of outgrowth and apoptosis for the terminal appendage: external genitalia development by concerted actions of BMP signaling [corrected]. Development 130, 6209-6220. 10.1242/dev.00846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi S., Takeda K., Oishi I., Nomi M., Ikeya M., Itoh K., Tamura S., Ueda T., Hatta T., Otani H. et al. (2000). Mouse Ror2 receptor tyrosine kinase is required for the heart development and limb formation. Genes Cells 5, 71-78. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00300.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiler K. (1989). The House Mouse: Atlas of Embryonic Development. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Tourette C., Farina F., Vazquez-Manrique R. P., Orfila A.-M., Voisin J., Hernandez S., Offner N., Parker J. A., Menet S., Kim J. et al. (2014). The Wnt receptor Ryk reduces neuronal and cell survival capacity by repressing FOXO activity during the early phases of mutant huntingtin pathogenicity. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001895 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton K. D., Freddo A. M., Wang S. and Gumucio D. L. (2016). Generation of intestinal surface: an absorbing tale. Development 143, 2261-2272. 10.1242/dev.135400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Cha S.-W., Zorn A. M. and Wylie C. (2013). Par6b regulates the dynamics of apicobasal polarity during development of the stratified Xenopus epidermis. PLoS One 8, e76854 10.1371/journal.pone.0076854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Cebrian C., Schnell S. and Gumucio D. L. (2018). Radial WNT5A-Guided Post-mitotic Filopodial Pathfinding Is Critical for Midgut Tube Elongation. Dev. Cell 46, 173-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Walton K. D. and Gumucio D. L. (2019). Signals and forces shaping organogenesis of the small intestine. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 132, 31-65. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver L. T., Austin S. and Cole T. J. (1991). Small intestinal length: a factor essential for gut adaptation. Gut 32, 1321-1323. 10.1136/gut.32.11.1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouda R. R., Bansraj M. R., de Jong A. W., Noordermeer J. N. and Fradkin L. G. (2008). Src family kinases are required for WNT5 signaling through the Derailed/RYK receptor in the Drosophila embryonic central nervous system. Development 135, 2277-2287. 10.1242/dev.017319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M., Udagawa J., Matsumoto A., Hashimoto R., Hatta T., Nishita M., Minami Y. and Otani H. (2010). Ror2 is Required for Midgut Elongation During Mouse Development. Dev. Dyn. 239, 941-953. 10.1002/dvdy.22212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T. P., Bradley A., McMahon A. P. and Jones S. (1999). A Wnt5a pathway underlies outgrowth of multiple structures in the vertebrate embryo. Development 126, 1211-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa S., McKinnon R. D., Kokel M. and Thomas J. B. (2003). Wnt-mediated axon guidance via the Drosophila Derailed receptor. Nature 422, 583-588. 10.1038/nature01522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K., Xu J., Liu Z., Sosic D., Shao J., Olson E. N., Towler D. A. and Ornitz D. M. (2003). Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development 130, 3063-3074. 10.1242/dev.00491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J., Kim H.-T., Lyu J., Yoshikawa K., Nakafuku M. and Lu W. (2011). The Wnt receptor Ryk controls specification of GABAergic neurons versus oligodendrocytes during telencephalon development. Development 138, 409-419. 10.1242/dev.061051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorn A. M. and Wells J. M. (2009). Vertebrate endoderm development and organ formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 25, 221-251. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.