To the Editor:

Risk of major salivary gland cancer (SGC) increases after a diagnosis of skin cancers,1,2 suggesting a shared risk factor such as exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR). However, the evidence supporting this association is limited.3,4

We examined the relationship between ambient UVR and risk of SGC by race/ethnicity and histologic subtype using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry program linked to US county-level, satellite-based ambient UVR. SEER counties were ranked by UVR and assigned quartiles 1 to 4 (lowest to highest) (Supplemental Fig 1; available via Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/ccsywx9fgx.2). Incidence rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated by using mixed-effects Poisson regression, adjusting for sex, attained age, year, and race and including SEER registry as a random effect. Numbers of SGC cases by sex and more than 20 subtypes in 2000 through 2016 are shown in Supplemental Table I (available via Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/ccsywx9fgx.2). Incidence of squamous cell carcinoma subtype (SCCSGC) in non-Hispanic white individuals was significantly higher than in those of other races/ethnicities (Supplemental Table II; available via Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/ccsywx9fgx.2).

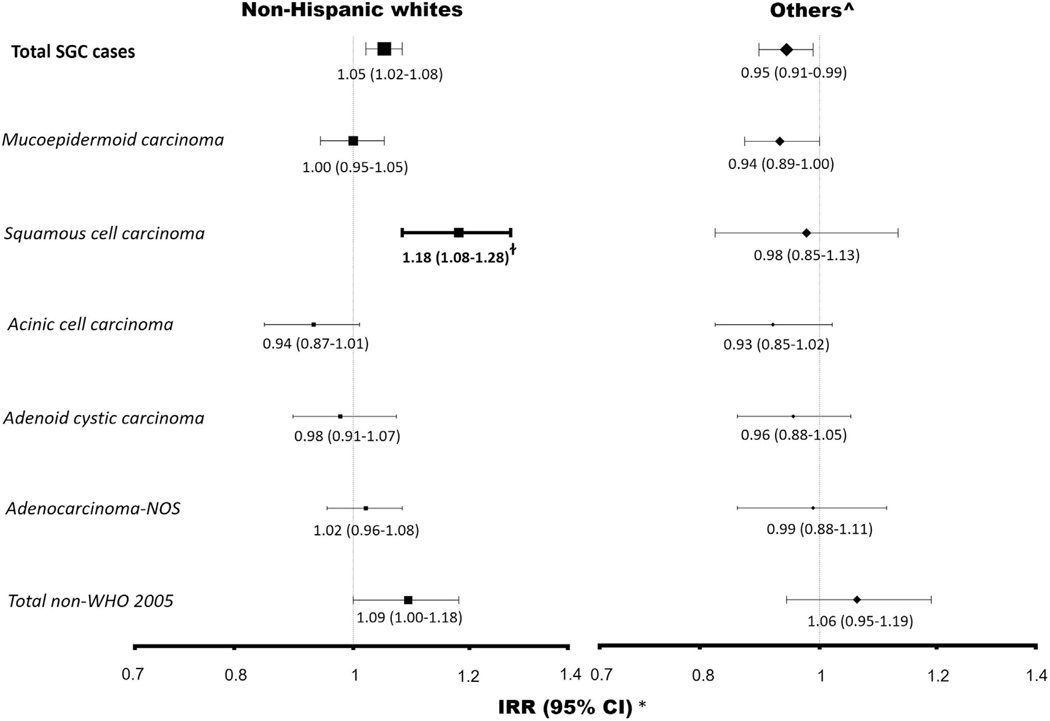

UVR was significantly associated with increased risks of SCCSGC in non-Hispanic white individuals (per 10 mW/m2; UVR incidence rate ratios, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.08–1.28; P = .0002). However, no association was found for other subtypes and in other races/ethnicities (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Major salivary gland cancer subtypes and ultraviolet radiation exposure.

Our results strengthen the evidence3 for UVR as a risk factor for the SCCSGC subtype, but there was little evidence to suggest associations between UVR and other subtypes. UVR may be related to increased risk of SCCSGC through immunosuppression. Another explanation for our UVR findings is that a subset of SCCSGC ascertained in our study included occult or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC). Previous clinical reports have indicated that distinguishing between primary SCCSGC and metastases of cSCC and other primary sites is difficult.5 Primary SCCSGC can be difficult to distinguish from metastatic cSCC using immunohistochemistry alone. Furthermore, tumor misclassification has recently been shown with the identification of UV-signature mutations in salivary neuroendocrine carcinoma, suggesting that these tumors represent metastatic cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma. One of the major strengths of this study is a sample size large enough to examine many SGC subtypes by race/ ethnicity, including at least 4 times the number of cases as the previous largest study (4,250 vs 18,168),4 with a broad range of ambient UVR. Our study has limitations, including a lack of data on personal UVR exposure. Second, misclassification of exposure may also have resulted because ambient UVR was linked to location of residence only at diagnosis. Third, residual confounding due to unmeasured putative risk factors may also affect our results.

In conclusion, UVR may not be a risk factor of overall SGC, except SCCSGC subtype. The presence of UV-signature mutations may be used in future studies to validate that a subset of SCCSGC represents metastatic cSCC. If confirmed, patients with SCCSGC may benefit from increased skin surveillance to search for an occult primary cSCC and to screen for additional skin cancers. Patients with high-risk cSCC (staging ≥ T3 by either American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition, or Brigham and Women’s Hospital system) may also benefit from oral screening for symptoms (eg, dry mouth, pain) to enable early detection of salivary gland metastases.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: Supported by the Intramural Research Program, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

IRB approval status: This study was exempt from IRB review because SEER does not have personal identifiers.

Reprints not available from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spanogle JP, Clarke CA, Aroner S, Swetter SM. Risk of second primary malignancies following cutaneous melanoma diagnosis: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62: 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wheless L, Black J, Alberg AJ. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and the risk of second primary cancers: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1686–1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spitz MR, Sider JG, Newell GR, Batsakis JG. Incidence of salivary gland cancer in the United States relative to ultraviolet radiation exposure. Head Neck Surg. 1988;10:305–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun EC, Curtis R, Melbye M, Goedert JJ. Salivary gland cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8: 1095–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Son E, Panwar A, Mosher CH, Lydiatt D. Cancers of the major salivary gland. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]