Abstract

Rostral forebrain structures, such as the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), send projections to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) and the parabrachial nucleus (PBN) that modulate taste-elicited responses. However, the proportion of forebrain-induced excitatory and inhibitory effects often differs when taste cell recording changes from the NST to the PBN. The present study investigated whether this descending influence might originate from a shared or distinct population of neurons marked by expression of somatostatin (Sst). In Sst-reporter mice, the retrograde tracers’ cholera toxin subunit B AlexaFluor-488 and -647 conjugates were injected into the taste-responsive regions of the NST and the ipsilateral PBN. In Sst-cre mice, the cre-dependent retrograde tracers’ enhanced yellow fluorescent protein Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) and mCherry fluorescent protein HSV were injected into the NST and the ipsilateral PBN. The results showed that ~40% of CeA-to-PBN neurons expressed Sst compared with ~ 23% of CeA-to-NST neurons. For both the CeA Sst-positive and -negative populations, the vast majority projected to the NST or PBN but not both nuclei. Thus, a subset of CeA-to-NST and CeA-to-PBN neurons are marked by Sst expression and are largely distinct from one another. Separate populations of CeA/Sst neurons projecting to the NST and PBN suggest that differential modulation of taste processing might, in part, rely on differences in local brainstem/forebrain synaptic connections.

Keywords: CeA, herpes simplex virus, NST, PBN, retrograde, taste

Introduction

In rodents, gustatory information from taste receptor cells in the tongue and palate is carried by branches of the facial (chorda tympani and greater superficial petrosal) and glossopharyngeal nerves to the rostral third of the medullary nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) (Contreras et al., 1982; Hamilton and Norgren, 1984; Corson et al., 2012). From the NST, ascending gustatory information reaches the pontine parabrachial nucleus (PBN; Ogawa et al., 1984: Di Lorenzo and Monroe, 1995; Cho et al., 2002a). Not surprisingly, neural processing in these 2 brainstem nuclei is critical for an animal’s ability to use gustatory information to guide ingestive behavior (Reilly et al., 1993; Spector et al., 1993; Grigson et al., 1997a, 1997b; Shimura et al., 1997b).

It is well established that neural processing of gustatory information in the NST and PBN is not static but subject to modulation by many factors (Chang and Scott, 1984; Giza et al., 1992; Nakamura and Norgren, 1995; Shimura et al., 1997a; Hajnal et al., 1999; Baird et al., 2001; Lundy and Norgren, 2004). For example, the PBN conveys gustatory information to ventral forebrain structures such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), and lateral hypothalamus (LH; Norgren, 1976; Li and Cho, 2006). These forebrain areas, in turn, send projections back to the gustatory NST and PBN (Moga et al., 1989; Moga et al., 1990a, 1990b; Saggu and Lundy, 2008; Kang and Lundy, 2009; Tokita et al., 2010). Electrical stimulation of the BNST, CeA, and LH produces varied effects of tastant-evoked responses recorded in the NST and PBN. Activation of the BNST and CeA predominately inhibited PBN taste responses, while inhibition and excitation occurred equally often during LH activation (Lundy and Norgren, 2001, 2004; Li et al., 2005; Li and Cho, 2006). For NST neurons, however, the most common effect of CeA and LH activation was excitatory, whereas BNST activation was predominately inhibitory (Li et al., 2002; Cho et al., 2003; Kang and Lundy, 2010). Thus, a single forebrain region can differentially affect gustatory processing depending on the whether the targeted neurons are in the NST or PBN.

One possibility is that distinct populations of forebrain neurons project to the NST and PBN. Indeed, previous research from our lab using rats demonstrated that largely separate populations of BNST, CeA, and LH neurons project to the NST and PBN (Kang and Lundy, 2009) with the largest source of descending input originating from the CeA (Kang and Lundy, 2009; Tokita et al., 2010). We also demonstrated both in rats and mice that CeA neurons marked by somatostatin expression (Sst) are a major source of descending input to the gustatory region of the PBN compared with those marked by corticotrophin-releasing hormone expression (Panguluri et al., 2009; Magableh and Lundy, 2014). Whether the NST and PBN of mice also are targeted by nonoverlapping populations of CeA neurons and whether descending projections from CeA/Sst-expressing cells are target-specific remains unknown. To this end, the current study used transgenic mouse strains combined with viral and nonviral injections of retrograde tracer to address this gap in knowledge.

Material and methods

Subjects

For cholera toxin subunit B retrograde tracer injections (CTb), Sst-cre mice (Jackson Laboratories, Sst) were bred with floxed-TdTomato mice (Jackson Laboratories, B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sor) to generate a reporter line that expressed TdTomato in Sst cell types (Sst/TdTomato line). Two male and 1 female reporter mice weighing 20–25 g were used. For retrograde Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) injections, we used 2 female and 1 male Sst-cre heterozygous mice (18–24 g). The animals were maintained in a temperature-controlled colony room on a 12-h light/dark cycle and allowed free access to normal rodent chow and distilled water. All procedures conformed to the National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgery

The mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of Ketamine/Xylazine [(100 mg/kg (K)/10 mg/kg (X)]. If needed, an additional dose of Ketamine (50 mg/kg) was administered to continue a deep level of anesthesia. The animals were placed on a feedback-controlled heating pad, and rectal temperature was monitored to maintain body temperature at 35±1 °C. Animals were secured in a stereotaxic instrument and the skull leveled with reference to bregma and lambda cranial sutures. Two small holes were drilled through the bone overlying the cerebellum to allow access to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) and PBN. The analgesic meloxicam (3 mg/kg) was administered prior to wound incision and again for at least 2 days postsurgery.

Electrophysiological recording

Gustatory NST and PBN neurons were identified by recording multiunit activity through a glass-coated tungsten microelectrode (resistance: 1–2 MΩ) while stimulating the anterior tongue with 0.1 M NaCl. Only the anterior two-thirds of the tongue were stimulated because numerous prior studies have demonstrated that CeA activation has a profound influence on brainstem taste cells that receive input via the chorda tympani nerve (Lundy and Norgren, 2001, 2004; Cho et al., 2002b, 2003; Kang and Lundy, 2010). Further, the concentration of NaCl used has been shown to produce a significant neural response in each “best-stimulus” class of NST and PBN neurons (Lundy and Norgren, 2001, 2004; Kang and Lundy, 2010). For access to the NST, the electrode was lowered at coordinates ranging from 6.0 to 6.2 mm posterior to bregma and 1.1–1.3 mm lateral to the midline according to mouse stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Typically, taste-evoked activity was encountered 3.7–3.9 mm ventral to the surface of the cerebellum. The coordinates for the PBN recordings were 5.1–5.3 mm posterior to bregma, 1.1–1.3 mm lateral to the midline, and 2.7–3.0 mm below the surface of the inferior colliculus. The surface of the brain was kept moist throughout surgery with physiological saline.

CTb tracer injections

Once the gustatory region was identified, the tungsten electrode was replaced by a 10-μL nanofil syringe (34-g beveled needle, World Precision Instruments) mounted in a microprocessor-controlled injector (UltraMicroPump, World Precision Instruments) attached to the stereotaxic instrument. The syringe was first front-loaded with light mineral oil followed by either a 0.2% solution of CTb AlexaFluor-488 conjugate (Invitrogen, cat#C34775) in phosphate-buffered saline or a 0.2% solution of CTb AlexaFluor-647 conjugate (Invitrogen, cat#C34778). A different syringe was used for each tracer conjugate. The microprocessor was set to deliver 75 nL of CTb to each site at a rate of 40 nL/min, and the syringe retracted 5 min postinjection. Five to 6 days following tracer injections, the animals were administered a lethal dose of Ketamine/Xylazine [(300 mg/kg (K)/30 mg/kg (X)] and perfused through the ascending aorta with 10 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were removed, blocked just rostral to the PBN, and postfixed overnight at 4 °C in the same fixative. Coronal sections (70 μm) were cut using a vibrating microtome.

HSV injections

The coordinates from electrophysiological recordings in the CTb experiments were used for injection of HSV into the NST (6.1 mm posterior to bregma, 1.3 mm lateral to the midline, and 3.9 mm ventral to the surface of the cerebellum) and PBN (5.2 mm posterior to bregma, 1.3 mm lateral to the midline, and 2.9 mm ventral to the surface of the inferior colliculus). The 10 μL nanofil syringe was first front-loaded with light mineral oil followed by either HSV-EF1alpha-DIO-mCherry (RN413, 2.5 × 109 infectious units/mL) or HSV-EF1alpha-DIO-EYFP (RN415, 2.5 × 109 infectious units/mL) (Rachael Neve, Massachusetts General Hospital). Because the mCherry and EYFP genes are preceded by DIO, a double-floxed inverse open reading frame, expression of transgene is restricted to Sst-expressing neurons. A different syringe was used for each virus. The microprocessor was set to deliver 300 nL of HSV to each site at a rate of 40 nL/min, and the syringe retracted 5 min postinjection. Three weeks following virus injections, the animals were administered a lethal dose of Ketamine/Xylazine [(300 mg/kg (K)/30 mg/kg (X)] and perfused through the ascending aorta with 10 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were removed, blocked just rostral to the PBN, and post-fixed overnight at 4°C in the same fixative. Coronal sections (60 μm) were cut using a vibrating microtome.

Data analysis

Cell bodies in the CeA positive for CTb-488, CTb-647, and TdTomato (Sst-reporter mice) or mCherry and EYFP (virus injected Sst-cre mice) were identified using sequential scanning with an Olympus confocal microscope. In every other section (8 sections/mouse), the number of fluorescent positive cells in each Z stack (3 μm/slice) was calculated and used for statistical analyses. The color segmentation function in Image J software was used to separate and count labeled neurons. The separate color channels were converted to 8-bit images (Figure 1A and B), auto threshold adjusted (white objects on black background, otsu or triangle method), and a Gaussian blur applied (sigma radius = 1) (Figure 1C and D). The appropriate scale was set (1.4 pixels/μm (40× magnification) or 0.85 pixels/μm (10× magnification)) and the analyze particles function used to count labeled cells in each channel (size ≥ 20 μm2) (Figure 1E and F). The image calculator function “AND” was used to identify overlapping pixels in the separate channels. Using the analyze particles function on the resultant image, overlapping elements with size ≥ 20 μm2 were considered to be a double- (Figure 1G) or triple-labeled cells (only for CTb injections; not shown). Manual counts on select sections were similar to automated calculations. Nonparametric 2-independent samples tests (Kolmogorov–Smirnov) were used for statistical analyses (SPSS 17.0). The results are presented as mean ± SE and a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Example of the process for automated cell counts using Image J software. Eight-bit images of separate color channels depicting retrograde-labeled Sst cells in the CeA resulting from HSV-Ef1α-DIO-EYFP injected into the NST (A) and HSV-Ef1α-DIO-mCherry into the PBN (B). The black and white images were auto threshold adjusted (otsu or triangle method) and a Gaussian blur applied (sigma radius = 1) (C,D). The analyze particles function was used to create a mask of labeled cells in each channel (size ≥ 20 μm2) (E, F). In this example with 2 color channels, the number of double-labeled cells was calculated using the image calculator function “AND” to identify overlapping pixels in the separate channels. Using the analyze particles function on the resultant image, overlapping elements with size ≥20 μm2 were considered to be double labeled (G).

Results

CTb injections

In each animal, the taste responsive region of the NST (Figure 2A) and PBN (Figure 2F) was electrophysiologically located by applying 0.1 M NaCl to the anterior tongue. Figure 2B–E shows photomicrograph examples of CTb-647 (white fluorescence) injected into the taste-responsive NST of an Sst-TdTomato reporter mouse. Neurons and fibers expressing Sst (red fluorescence) filled the rostrocaudal extent of the NST. Microscopic examination of medullary tissue revealed that CTb injections were concentrated in the medial subdivisions of the NST with minimal spread into the ventrally located reticular formation or laterally located dorsomedial spinal trigeminal nucleus. Numerous labeled neurons were observed in the medial vestibular nucleus immediately dorsal to the NST. This might be the result of tracer spread along the injection needle tract or reflect vestibular input to the NST (Balaban and Beryozkin, 1994). Nevertheless, we have not observed retrograde-labeled cells in the CeA when injections were misplaced in the medial vestibular nucleus dorsal to the NST. Photomicrograph examples of CTb-488 (green fluorescence) injected into the taste-responsive PBN of the same mouse are shown in Figure 2G–I. Neurons and fibers expressing Sst (red fluorescence) surrounded the medial, central lateral, ventral lateral, and waist portions of the PBN. Microscopic examination of pontine tissue revealed that CTb injections predominately targeted the above PBN sub nuclei with minimal spread into the rostral and external regions. A summary diagram of the CTb injections and their relative spread is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Electrophysiological recordings of taste-evoked responses to 0.1 M NaCl in NST (A) and PBN (F). Red lines show neural activity during application of NaCl to the anterior tongue while black lines indicate water application. Fluorescent images of CTb-647 (white) injection in the gustatory responsive NST (B–F) and CTb-488 (green) in the gustatory responsive PBN (G–I) from case #1704. Sections are arranged from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom). White dots outline the approximate boundaries of the NST and the superior cerebellar peduncle (scp) in the PBN. Red fluorescence indicates Sst-expressing fibers and neurons. Yellow fluorescence (G–I) indicates overlap between Sst-expressing neural elements and CTb-488 injection. The approximate level relative to bregma is shown at the bottom left of each photomicrograph. Magnification was 10× (0.85 pixels/μm). Abbreviations: Cb, cerebellum; DMsp5, dorsomedial spinal trigeminal nucleus; anterior part; LC, locus coeruleus; LPBV, lateral parabrachial nucleus, ventral part; MPB, medial parabrachial nucleus; MVeMC, medial vestibular nucleus, magnocellular part; PCRtA, parvicellular reticular nucleus, alpha part; PBW, parabrachial nucleus, waist part; scp, superior cerebellar peduncle; SolM, nucleus of the solitary tract, medial part; SuVe, superior vestibular nucleus.

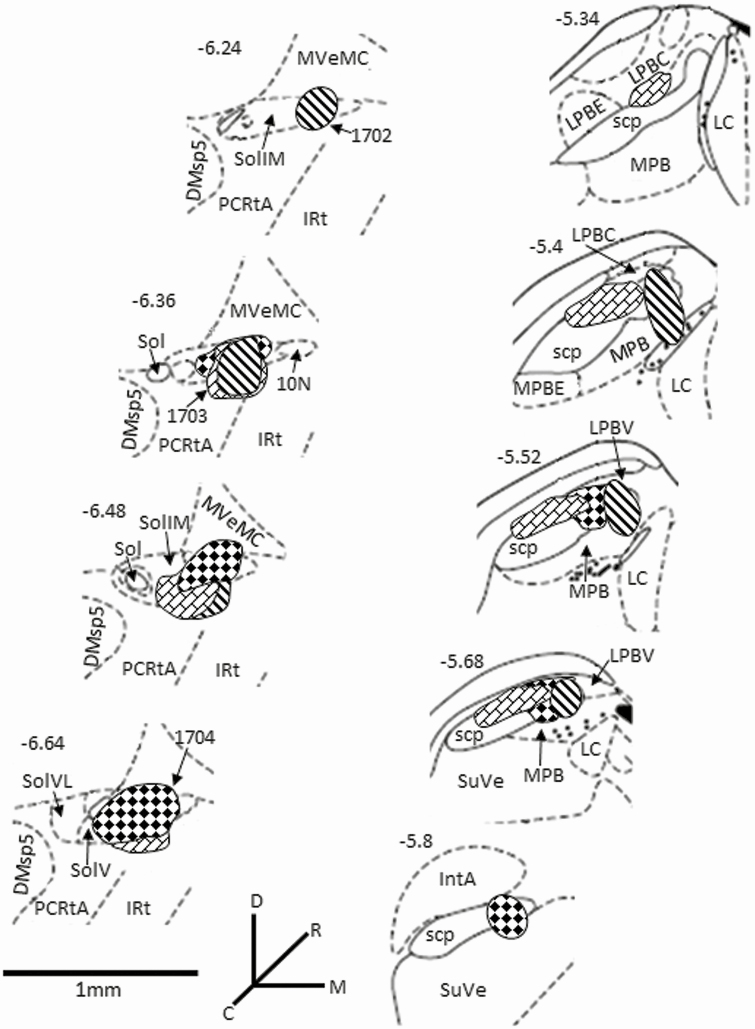

Figure 3.

The different fill patterns represent the extent of individual tracer injections concentrated in the rostral regions of the NST (left panels) and caudal regions of PBN (right panels). Sections are arranged from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom) and medial is to the right. The approximate levels relative to bregma are indicated at the top left of each image (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Abbreviations: DMsp5, dorsomedial spinal trigeminal nucleus; anterior part; IRt, intermediate reticular nucleus; IntA, interposed cerebellar nucleus, anterior part; LC, locus coeruleus; LPBC, lateral parabrachial nucleus, central part; LPBE, lateral parabrachial nucleus, external part; LPBV, lateral parabrachial nucleus, ventral part; MPB, medial parabrachial nucleus; MPBE, medial parabrachial nucleus external part; MVeMC, medial vestibular nucleus, magnocellular part; PCRtA, parvicellular reticular nucleus, alpha part; scp, superior cerebellar peduncle; Sol, solitary tract; SoliM, nucleus of the solitary tract, intermediate.Part; SolM, nucleus of the solitary tract, medial part; SolV, solitary nucleus, ventral part; SuVe, superior vestibular nucleus.

Robust retrograde labeling was observed throughout the rostral caudal extent of the CeA. The CeA was identified as the area ~0.7–1.9 mm posterior to bregma, ventral to the striatum, medial to the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala, and lateral to the optic tract. Low-power photomicrograph examples of retrograde labeled (CeA-to-PBN, white fluorescence; CeA-to-NST, green fluorescence) and Sst-expressing neurons (red fluorescence) at 4 different levels of the CeA are shown in Figure 4A–D. Panels E–H show corresponding stereotaxic atlas drawings depicting the general location of CeA neurons projecting to the NST (green) and PBN (blue). No attempt was made to signify double-labeled neurons or provide an exact representation of the total number of cells in each photomicrograph. Consistent with previous tracing studies, Sst neurons are densely packed throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the CeA where neurons projecting to the NST and PBN are largely intermingled (Kang and Lundy, 2009; Panguluri et al., 2009; Magableh and Lundy, 2014).

Figure 4.

(A–D) Representative photomicrographs of CeA/Sst neurons (red) and neurons projecting to the NST (green) and PBN (white) from case #1702. The white dotted lines outline the approximate boundaries of the CeC, CeL, and CeM divisions of the CeA. The approximate levels relative to bregma are indicated at the bottom left corner in each photomicrograph (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Magnification of fluorescent images was 10× (0.85 pixels/μm). (E–H) Corresponding diagrams labeled with amygdala subnuclei as defined in Paxinos and Franklin (2001). The general location of retrograde labeled neurons is represented by green (NST projecting) and blue (PBN projecting) dots. The black scale bar below the atlas drawings is 1 mm. Abbreviations: BLA, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, anterior part; BMA, basomedial amygdaloid nucleus, anterior part; CeC, central amygdaloid nucleus, capsular part; CeL, central amygdaloid nucleus, lateral division; CeM, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial division; IPAC, interstitial nucleus of the posterior limb of the anterior commissure; LaVL, lateral amygdaloid nucleus, ventrolateral part; opt, optic tract.

We counted a total of 1233 CeA neurons that projected to the NST and 1362 to the PBN. Retrograde-labeled cells fell into 1 of 6 groups: NST only Sst positive, NST only Sst negative, PBN only Sst positive, PBN only Sst negative, NST/PBN Sst positive, and NST/PBN Sst negative (Figure 5A–D). The average number of retrograde-labeled CeA cells was comparable between injection sites (Figure 6 total; Kolmogorov–Smirnov F = 0.57, P = 0.89). The majority of the CeA-to-NST population was Sst negative (Kolmogorov–Smirnov F = 2.0, P < 0.01), while the CeA-to-PBN population was more equally split between Sst-negative and Sst-positive cells (Kolmogorov–Smirnov F = 0.86, P = 0.44).

Figure 5.

Representative high-power photomicrographs of the CeA showing fluorescent labeling from CTb-488 (A, green PBN projecting neurons) and CTb-647 (B, white NST projecting neurons) injections in case #1704. (C) Sst-positive neurons marked by TdTomato reporter expression (red). (D) Merged image of separate color channels. Filled arrowhead: example of Sst-positive neuron that only projects to the PBN (yellow). Filled diamond: example of Sst-positive neuron that only projects to the NST. Filled circle: example of Sst-positive neuron that projects both to the NST and PBN. Magnification was 40× (1.40 pixels/μm). The white scale bar at bottom right in panel A is 20 μm.

Figure 6.

The per section average of retrograde-labeled neurons in the CeA following injections of CTb into the gustatory NST (open bars) and PBN (cross-hatched bars) of Sst/TdTomato reporter mice. *, significantly different from PBN Sst positive.

Expressed as a percentage of their respective population, a significantly greater proportion of CeA-to-PBN neurons expressed Sst (~40%) compared with CeA-to-NST neurons (~23%) (Figure 7A, Kolmogorov–Smirnov F = 1.73, P < 0.01). A statistically significant difference between injection site also was evident for the remaining Sst-negative portion of the populations (Figure 7B, Kolmogorov–Smirnov F = 1.58, P = 0.01). For both the CeA Sst-positive (Figure 7A) and -negative populations (Figure 7B), the vast majority had a single target (i.e., NST only or PBN only) with a smaller proportion being dual-target cells. Statistically significant differences were not observed between injection sites for single- or dual-target neurons (Kolmogorov–Smirnov F’s ≥ 0.44, P’s ≥ 0.4).

Figure 7.

The mean percentage of CeA Sst-positive (A) and -negative (B) neurons following injections of CTb into the gustatory NST (open bars) and PBN (cross-hatched bars) of Sst/TdTomato reporter mice. Relative to the overall number of NST and PBN projecting cells, the majority of Sst-positive and -negative neurons projected to a single target (i.e., either the NST or PBN). *, significantly different from NST overall Sst positive.

HSV injections

To confirm the above results obtained from CTb injections, we injected cre-dependent HSV’s into the NST and PBN of Sst-cre mice. Figure 8A–D shows photomicrograph examples of HSV-Ef1α-DIO-EYFP injected into the NST. Microscopic examination of each injection site revealed that green fluorescence (cells, axons, and dendrites) largely filled the NST at each level. The green fluorescent cells in the NST likely reflect Sst-expressing interneurons, while those in surrounding areas indicate Sst neurons that project to the NST or possibly virus spread outside the NST (Travers, 1988; Beckman and Whitehead, 1991; Balaban and Beryozkin, 1994; Corson et al., 2012). The red fluorescent cells represent Sst neurons that project to the PBN (Travers, 1988; Murakami et al., 2002; Dallel et al., 2004). A few cells were positive for both EYFP and mCherry (yellow fluorescence) indicative of Sst neurons that project to or within the NST as well as to the PBN.

Figure 8.

Representative fluorescent images resulting from the injection of HSV-Ef1α-DIO-EYFP into the NST (A–D, green) and HSV-Ef1α-DIO-mCherry into the PBN (E–H, red) of a Sst-cre mouse. Sections are arranged from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom). White dots outline the approximate boundaries of the NST and the superior cerebellar peduncle (scp) in the PBN. Within the NST, red fluorescence indicates Sst-expressing neurons that project to the PBN, while yellow fluorescence indicates Sst-expressing neurons that project to the PBN and locally within the NST. Within the PBN, the red fluorescent cells in the PBN indicate Sst-expressing interneurons, while those in surrounding areas such as LC indicate Sst neurons that project to the PBN. The green fluorescent cells represent Sst-positive PBN-to-NST projection neurons, while green fluorescent fibers likely represent retrograde-labeled axons from higher structures. The approximate level relative to bregma is shown at the bottom left of each photomicrograph. Magnification was 10× (0.85 pixels/μm). Abbreviations: Cb, cerebellum; DMsp5, dorsomedial spinal trigeminal nucleus; anterior part; LC, locus coeruleus; LPBE, lateral parabrachial nucleus, external part; LPBV, lateral parabrachial nucleus, ventral part; MPB, medial parabrachial nucleus; MVeMC, medial vestibular nucleus, magnocellular part; MVePC, medial vestibular nucleus, parvicellular part; PCRtA, parvicellular reticular nucleus, alpha part; PBW, parabrachial nucleus, waist part; SolM, nucleus of the solitary tract, medial part; scp; superior cerebellar peduncle; SpVe, spinal vestibular nucleus.

Photomicrograph examples of HSV-Ef1α-DIO-mCherry injected into the PBN of the same mouse are shown in Figure 8E–H where red fluorescence (cells, axons, and dendrites) largely surrounded the superior cerebellar peduncle (scp) at each level. The red fluorescent cells in the PBN likely reflect Sst-expressing interneurons, while those in surrounding areas such as LC indicate Sst neurons that project to the PBN or possibly virus spread outside the PBN (Giehl and Mestres, 1995; Luppi et al., 1995). The green fluorescent cells represent Sst-positive PBN-to-NST projection neurons (Karimnamazi and Travers, 1998), while green fluorescent fibers likely represent retrograde-labeled axons from higher structures. Despite greater spread of the larger volume virus injections relative to CTb injections, the resulting label in the CeA was remarkably similar.

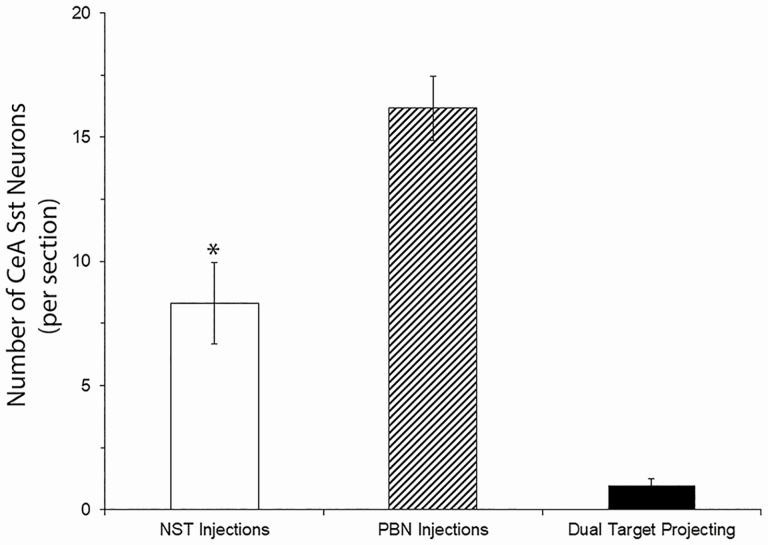

Dense expression of fluorescent markers was observed throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the amygdala. Low-power photomicrograph examples of retrograde-labeled Sst-expressing neurons at 4 different levels of the CeA are shown in Figure 9A–D. Panels E–H show corresponding stereotaxic atlas drawings depicting the general location of CeA/Sst neurons projecting to the NST (green) and PBN (red). No attempt was made to signify double-labeled neurons (yellow in Figure 9A–D) or provide an exact representation of the total number of cells in each photomicrograph. We counted a total of 241 CeA/Sst neurons that projected to the NST and 469 projecting to the PBN. On average, a greater number of CeA/Sst neurons projected to the PBN (16.1 ± 1.3 cells per section) compared with the NST (8.3 ± 1.6 cells per section) (Figure 10; Kolmogorov–Smirnov F = 2.2, P < 0.01). Out of the 710 retrograde-labeled neurons, only 28 contained both fluorescent markers and were considered dual-target neurons (Figure 10; 0.9 ± 0.2 cells per section). Expressed as a percentage of their respective population, >90% of CeA/Sst cells project either to the NST or PBN (Figure 11A). Statistically significant differences were not observed between injection sites for single- or dual-target neurons (Kolmogorov–Smirnov F’s = 0.65, P’s = 0.78). Comparison of both experimental methods used in the present report revealed a similarly small percentage of CeA/Sst neurons that project to both brainstem gustatory nuclei (Figure 11B; Kolmogorov–Smirnov F’s ≥ 0.5, P’s ≥ 0.8). Thus, CeA cells mostly project either to the NST or PBN and a subset of each population expresses Sst.

Figure 9.

(A–D) Representative photomicrographs of CeA/Sst neurons projecting to the NST (green) and PBN (red) from HSV injections depicted in Figure 8. Yellow fluorescence indicates Sst neurons that project both to the NST and PBN. The white-dotted lines outline the approximate boundaries of the CeC, CeL, and CeM divisions of the CeA. The approximate levels relative to bregma are indicated at the bottom left corner in each photomicrograph (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Magnification of fluorescent images was 10× (0.85 pixels/μm). (E–H) Corresponding diagrams labeled with amygdala sub nuclei as defined by Paxinos and Franklin (2001). The general location of retrograde-labeled neurons is represented by green (NST projecting) and red (PBN projecting) dots. The black scale bar below the atlas drawings is 1 mm. Abbreviations: BLA, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, anterior part; BMA, basomedial amygdaloid nucleus, anterior part; CeC, central amygdaloid nucleus, capsular part; CeL, central amygdaloid nucleus, lateral division; CeM, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial division; IPAC, interstitial nucleus of the posterior limb of the anterior commissure; LaVL, lateral amygdaloid nucleus, ventrolateral part; opt, optic tract.

Figure 10.

The per section average of retrograde labeled Sst neurons in the CeA following HSV injections of into the NST and PBN of a Sst-cre mice. Open bar represents the average number of Sst cells that only projected to the NST, cross-hatched bar Sst cells that only projected to the PBN, and filled bar Sst cells that projected both to the NST and PBN. *, significantly different from PBN injections.

Figure 11.

(A) The mean percentage of single- and double-labeled Sst neurons in the CeA following HSV injections into the NST (open bars) and PBN (cross-hatched bars). (B) Comparison of the percentage of dual-target Sst neurons calculated following CTb (open bars) and HSV (cross-hatched bars) injections into the NST and PBN. Both experimental methods resulted in a low percentage of CeA/Sst neurons that projected both nuclei.

Discussion

The objective of the present experiments was to further delineate neural populations in the CeA that projects to the gustatory regions of the NST and PBN. The present findings mirror results from previous studies showing that the NST and PBN are largely innervated by distinct populations of CeA neurons (Kang and Lundy, 2009) and, at least for the PBN, a large portion of CeA-to-PBN neurons express the neuropeptide Sst (Panguluri et al., 2009: Magableh and Lundy, 2014). The present results extend these observations by demonstrating that a subset of CeA-to-NST neurons also express Sst and are largely distinct from CeA-to-PBN Sst neurons.

Although the HSV injections produced greater spread in the rostrocaudal orientation compared with the CTb injections, the resultant retrograde labeling was overall in agreement. Retrograde-labeled Sst neurons were observed throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the CeA and most were found to be single-target cells projecting to either the NST or PBN with a much smaller population projecting to both brainstem nuclei. One difference between these CeA/Sst populations was that a significantly higher proportion innervated the PBN compared with the NST. Approximately 45% of CeA-to-PBN neurons were Sst positive, whereas Sst expression only accounted for about 25% of CeA-to-NST neurons. A previous study in mice reported an identical percentage of CeA-to-PBN neurons that express Sst (Magableh and Lundy, 2014). Despite this difference in the extent to which Sst neurons contribute to CeA-to-NST and CeA-to-PBN pathways, they likely influence neural processing of taste information in the brainstem.

Prior investigations in rats and/or hamsters demonstrate that the CeA modulates taste responsive neurons in the NST and PBN, which is often differential. In rats and hamsters, the most common effect of CeA stimulation on NST taste cells was excitatory (Cho et al., 2003; Kang and Lundy, 2010). One synapse further along in the PBN, inhibition of taste cells in response to CeA stimulation predominated (Lundy and Norgren, 2001, 2004; Li et al., 2005). The present results showing that separate populations of CeA neurons project to the NST and PBN but express a common neuropeptide suggest that differential modulation of taste processing might rely on differences in local brainstem/forebrain synaptic connections. A recent study from our lab demonstrated that CeA-to-PBN Sst axon terminals co express GABA and predominately synapse with non-GABAergic postsynaptic neural elements (Lundy, 2020). The synaptic organization of CeA-to-NST Sst axon terminals awaits investigation but given the substantial presence of GABA interneurons in the NST it is likely that CeA Sst axon terminals co express GABA and predominately synapse with GABAergic postsynaptic neural elements. Such a synaptic arrangement could set up descending disinhibition of NST taste cells. Another possibility is that other subsets of CeA-to-NST and CeA-to-PBN neurons express distinct neurochemicals.

Although our research demonstrates that Sst neurons of CeA origin represent 1 component of descending inputs to the NST and PBN, the molecular identity of the Sst-negative population remains unclear. This group of neurons also largely projected to either the NST or PBN as well as constituted the bulk of projections to the NST (~75%) and more than 50% of the projections to the PBN. At least for the CeA-to-PBN neurons, we have previously shown that a small subset of neurons express corticotrophin-releasing hormone (Panguluri et al., 2009; Magableh and Lundy, 2014). The molecular identity of the remaining CeA-to-NST and CeA-to-PBN neurons could include 1 or more of the other numerous neurochemicals present in the CeA (Moga and Gray, 1985; McCullough et al., 2018). For example, CeA-serotonin receptor Htr2a and CeA-neurotensin expressing neurons contribute to ingestive behavior via interactions with the PBN (Douglass et al., 2017; Torruella-Suarez et al., 2020). If and how any of these CeA cell types influence neural processing of taste information in the brainstem remains unknown. Clearly, additional research is needed to understand the neurochemicals and neural circuitry that mediates top-down modulation of central taste processing and its impact on taste-guided behavior.

In conclusion, a clear understanding of the true impact that centrifugal regulation of taste processing has on taste-guided behavior awaits experiments that independently manipulate the relevant descending neurochemical pathways. Our studies shed light on 1 candidate neurochemical demonstrating that CeA/Sst-to-PBN and CeA/Sst-to-NST pathways arise from largely distinct neural populations. That these cell populations are distinct provides the opportunity for future investigations to delineate their contribution(s) to taste processing and ingestive behaviors.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Rachael Neve, co-director of the Gene Delivery Technology Core at Massachusetts General Hospital, for HSV’s.

Funding

The project described was supported by University of Louisville School of Medicine Bridge Award and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21DC015759. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Baird JP, Travers SP, Travers JB. 2001. Integration of gastric distension and gustatory responses in the parabrachial nucleus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 281(5):R1581–R1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban CD, Beryozkin G. 1994. Vestibular nucleus projections to nucleus tractus solitarius and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve: potential substrates for vestibulo-autonomic interactions. Exp Brain Res. 98(2):200–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman ME, Whitehead MC. 1991. Intramedullary connections of the rostral nucleus of the solitary tract in the hamster. Brain Res. 557(1-2):265–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang FC, Scott TR. 1984. Conditioned taste aversions modify neural responses in the rat nucleus tractus solitarius. J Neurosci. 4(7):1850–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YK, Li CS, Smith DV. 2002a. Gustatory projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the parabrachial nuclei in the hamster. Chem Senses. 27(1):81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YK, Li CS, Smith DV. 2002b. Taste responses of neurons of the hamster solitary nucleus are enhanced by lateral hypothalamic stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 87(4):1981–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YK, Li CS, Smith DV. 2003. Descending influences from the lateral hypothalamus and amygdala converge onto medullary taste neurons. Chem Senses. 28(2):155–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras RJ, Beckstead RM, Norgren R. 1982. The central projections of the trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves: an autoradiographic study in the rat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 6(3):303–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson J, Aldridge A, Wilmoth K, Erisir A. 2012. A survey of oral cavity afferents to the rat nucleus tractus solitarii. J Comp Neurol. 520(3):495–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallel R, Ricard O, Raboisson P. 2004. Organization of parabrachial projections from the spinal trigeminal nucleus oralis: an anterograde tracing study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 470(2):181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo PM, Monroe S. 1995. Corticofugal influence on taste responses in the nucleus of the solitary tract in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 74(1):258–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass AM, Kucukdereli H, Ponserre M, Markovic M, Gründemann J, Strobel C, Alcala Morales PL, Conzelmann KK, Lüthi A, Klein R. 2017. Central amygdala circuits modulate food consumption through a positive-valence mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 20(10):1384–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giehl K, Mestres P. 1995. Somatostatin-mRNA expression in brainstem projections into the medial preoptic nucleus. Exp Brain Res. 103(3):344–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giza BK, Scott TR, Vanderweele DA. 1992. Administration of satiety factors and gustatory responsiveness in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the rat. Brain Res Bull. 28(4):637–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS, Shimura T, Norgren R. 1997a. Brainstem lesions and gustatory function: III. The role of the nucleus of the solitary tract and the parabrachial nucleus in retention of a conditioned taste aversion in rats. Behav Neurosci. 111(1):180–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS, Shimura T, Norgren R. 1997b. Brainstem lesions and gustatory function: II. The role of the nucleus of the solitary tract in Na+ appetite, conditioned taste aversion, and conditioned odor aversion in rats. Behav Neurosci. 111(1):169–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnal A, Takenouchi K, Norgren R. 1999. Effect of intraduodenal lipid on parabrachial gustatory coding in awake rats. J Neurosci. 19(16):7182–7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton RB, Norgren R. 1984. Central projections of gustatory nerves in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 222(4):560–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Lundy RF. 2009. Terminal field specificity of forebrain efferent axons to brainstem gustatory nuclei. Brain Res. 1248:76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Lundy RF. 2010. Amygdalofugal influence on processing of taste information in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat. J Neurophysiol. 104(2):726–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimnamazi H, Travers JB. 1998. Differential projections from gustatory responsive regions of the parabrachial nucleus to the medulla and forebrain. Brain Res. 813(2):283–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Cho YK, Smith DV. 2002. Taste responses of neurons in the hamster solitary nucleus are modulated by the central nucleus of the amygdala. J Neurophysiol. 88(6):2979–2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Cho YK, Smith DV. 2005. Modulation of parabrachial taste neurons by electrical and chemical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus and amygdala. J Neurophysiol. 93(3):1183–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Cho YK. 2006. Efferent projection from the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis suppresses activity of taste-responsive neurons in the hamster parabrachial nuclei. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 291(4):R914–R926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundy R. 2020. Comparison of GABA, somatostatin, and corticotrophin-releasing hormone expression in axon terminals that target the parabrachial nucleus. Chem Senses. 45(4):275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundy RF Jr, Norgren R. 2001. Pontine gustatory activity is altered by electrical stimulation in the central nucleus of the amygdala. J Neurophysiol. 85(2):770–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundy RF Jr, Norgren R. 2004. Activity in the hypothalamus, amygdala, and cortex generates bilateral and convergent modulation of pontine gustatory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 91(3):1143–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppi PH, Aston-Jones G, Akaoka H, Chouvet G, Jouvet M. 1995. Afferent projections to the rat locus coeruleus demonstrated by retrograde and anterograde tracing with cholera-toxin B subunit and Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. Neuroscience. 65(1):119–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magableh A, Lundy R. 2014. Somatostatin and corticotrophin releasing hormone cell types are a major source of descending input from the forebrain to the parabrachial nucleus in mice. Chem Senses. 39(8):673–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough KM, et al. , 2018. Quantified coexpression analysis of central amygdala subpopulations. eNeuro. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moga MM, Gray TS. 1985. Evidence for corticotropin-releasing factor, neurotensin, and somatostatin in the neural pathway from the central nucleus of the amygdala to the parabrachial nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 241(3):275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moga MM, Herbert H, Hurley KM, Yasui Y, Gray TS, Saper CB. 1990a. Organization of cortical, basal forebrain, and hypothalamic afferents to the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 295(4):624–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moga MM, Saper CB, Gray TS. 1989. Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: cytoarchitecture, immunohistochemistry, and projection to the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 283(3):315–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moga MM, Saper CB, Gray TS. 1990b. Neuropeptide organization of the hypothalamic projection to the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 295(4):662–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami DM, Erkman L, Hermanson O, Rosenfeld MG, Fuller CA. 2002. Evidence for vestibular regulation of autonomic functions in a mouse genetic model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99(26):17078–17082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Norgren R. 1995. Sodium-deficient diet reduces gustatory activity in the nucleus of the solitary tract of behaving rats. Am J Physiol. 269(3 Pt 2):R647–R661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren R. 1976. Taste pathways to hypothalamus and amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 166(1):17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H, Imoto T, Hayama T. 1984. Responsiveness of solitario-parabrachial relay neurons to taste and mechanical stimulation applied to the oral cavity in rats. Exp Brain Res. 54(2):349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panguluri S, Saggu S, Lundy R. 2009. Comparison of somatostatin and corticotrophin-releasing hormone immunoreactivity in forebrain neurons projecting to taste-responsive and non-responsive regions of the parabrachial nucleus in rat. Brain Res. 1298:57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ, 2001. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego (CA): Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S, Grigson PS, Norgren R. 1993. Parabrachial nucleus lesions and conditioned taste aversion: evidence supporting an associative deficit. Behav Neurosci. 107(6):1005–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saggu S, Lundy RF. 2008. Forebrain neurons that project to the gustatory parabrachial nucleus in rat lack glutamic acid decarboxylase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 294(1):R52–R57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura T, Komori M, Yamamoto T. 1997a. Acute sodium deficiency reduces gustatory responsiveness to NaCl in the parabrachial nucleus of rats. Neurosci Lett. 236(1):33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura T, Norgren R, Grigson PS, Norgren R. 1997b. Brainstem lesions and gustatory function: I. The role of the nucleus of the solitary tract during a brief intake test in rats. Behav Neurosci. 111(1):155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector AC, Grill HJ, Norgren R. 1993. Concentration-dependent licking of sucrose and sodium chloride in rats with parabrachial gustatory lesions. Physiol Behav. 53(2):277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokita K, Inoue T, Boughter JD Jr. 2010. Subnuclear organization of parabrachial efferents to the thalamus, amygdala and lateral hypothalamus in C57BL/6J mice: a quantitative retrograde double labeling study. Neuroscience. 171(1):351–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torruella-Suárez ML, Vandenberg JR, Cogan ES, Tipton GJ, Teklezghi A, Dange K, Patel GK, McHenry JA, Hardaway JA, Kantak PA, et al. 2020. Manipulations of central amygdala neurotensin neurons alter the consumption of ethanol and sweet fluids in mice. J Neurosci. 40(3):632–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JB. 1988. Efferent projections from the anterior nucleus of the solitary tract of the hamster. Brain Res. 457(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]