Abstract

Background:

Consent forms are an important educational tool that helps cancer patients decide on whether or not to enroll on a clinical trial, but wordiness potentially detracts from their educational value.

Methods:

This single institution study examined word counts of consent forms for all phase I, II, and III solid tumor clinical trials between 2004 and 2010. Consent forms were categorized by trial funding source: 1) pharmaceutical company; 2) National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN); 3) R01- or other non-government grants; and 4) mixed (funding from multiple sources).

Results:

315 consent forms were studied; these included 106 (34%) pharmaceutical company; 145 (46%) NCTN; 44 (14%) R01-type; and 20 (6%) mixed. The overall median word count was 5,129 words per consent form (interquartile range (IQR) range: 4,226 to 6,695). The median word counts per consent form (IQR) were 5648 (4814, 6803), 5243 (4139, 6932), 4365 (3806, 5124), and 4319 (3862, 5944), respectively, based on the above funding sources, showing that pharmaceutical company trial consent forms had the highest median word count. Of note, phase of trial was associated with consent form length (phase III were wordier), and consent forms manifested a consistent increase in wordiness over time.

Conclusion:

These observations underscore a timely need to find ways to limit the verbosity of consent forms, particularly in those from pharmaceutical company trials.

Keywords: consent forms, education, wordiness, verbosity, comprehension, clinical trials

INTRODUCTION

Too much verbiage can obfuscate meaning. The possibility of such lost meaning is relevant to patient consent forms, which are a necessary component of enrolling patients into clinical trials. Consent forms serve as educational tools for patients and their families to understand the risks and benefits of trial participation, and they typically require a formal patient signature prior to trial enrollment. However, some have voiced concerns that excessive detail on trial procedures, excessive itemization and discussion of adverse events, and excessive disclaimers on liability might be detracting from the true educational value of these documents:

“I’m concerned about the increasing length of consent forms for clinical trials. Over time, I’ve seen consent forms get so long that I’m not sure any prospective subject can understand them, even if they’re written at the recommended 6th – 8th grade reading level….”

[1]

Striking a balance between number of words and patient comprehension is relevant to cancer clinical trials. Cancer clinical trials are increasing in complexity with emerging new cancer drugs that have unknown side effect profiles and that call for extensive patient testing and monitoring. The need to fully inform cancer patients might give rise to wordier consent forms, which may ironically leave patients less informed, cause confusion from information overload, and perhaps even result in greater hesitation to enroll on the trial in question.

Along these lines, the increasingly dominant involvement of pharmaceutical companies in cancer drug development and their assertive patient recruitment timelines prompt the question of whether the source of funding for a clinical trial might influence the length of a consent form and whether the pressures to recruit patients to cancer clinical trials might generate more streamlined consent forms. Alternatively, one might question whether the legal aspects of clinical trial recruitment are, in fact, generating longer consent forms. A recent quote on this topic is telling, “Most companies have issues balancing patient-centric language and lay language and all the legal-ese and scientific concepts” [2].

The current study examined word counts in cancer clinical trial consent forms from the vantage point of funding source. To our knowledge, previous studies have not examined consent forms in this manner, but such information is critical to our understanding of how to enable cancer patients to make the best possible decision about whether or not to enroll on a cancer clinical trial.

METHODS

Overview.

This single-institution study was designed to evaluate the wordiness of consent forms for cancer clinical trials. The Mayo Clinic Cancer Center and the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB) had previously reviewed all consent forms for accuracy of content and for conformation to an 8th grade reading level, enabling the current study to focus only on word count.

Choice of Trials and Word Count.

All consent forms for phase I, II, and III solid tumor cancer clinical trials conducted between 2004 and early 2010 were included. These years were chosen because 2004 marked a dramatic rise in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s number of drug approvals [3]. Limiting the study to 2010 provided adequate follow up to assess completion of patient enrollment to the trials. Consent forms were converted to a Microsoft Word® document, if possible, and were assessed for word count with this software application or with Translator’s Abacus.®

Consent Form and Trial Categorization.

Consent forms for trials were categorized by funding source: 1) pharmaceutical company-funded (a pharmaceutical company wrote and funded the trial); 2) government, cooperative group-funded (now referred to as the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN); 3) R01- or other non-government-funded grants (written by an academic investigator); and 4) a mixed category that included trials funded from multiple sources. Trials were further categorized based on phase of trial, as per well-accepted definitions from the National Cancer Institute, and by year enrollment was initiated [4].

Trial Completion.

The National Institute of Health website -- www.clinicaltrials.gov -- was used to assess whether a trial had completed its planned enrollment. Similar information was gleaned from institutional sources, particularly for single-institution trials.

Analyses.

Median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to summarize word count overall and by funding source. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to test the association between trial characteristics of consent forms and funding source. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate whether there were differences in the median word count by funding source, phase of the trial, and the year the trial opened. If the overall test of median differences was significant, the Dwass, Steel, Critchlow-Fligner Method was used for testing all pairwise comparisons because of an absence of a natural reference group [5]. The Jonckheere-Terpstra Test was used to test for an increasing trend in median word count by the year the trial opened [6]. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to test for differences in median word count and trial accrual goal. Significance level was set at two-sided 0.05 [7]. SAS statistical software, version 9.4 was used to perform the analyses.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Consent Forms and Trials.

Three hundred fifteen consent forms were reviewed. Based on funding source, these consent forms were categorized as follows: 106 (34%) pharmaceutical company; 145 (46%) NCTN; 44 (14%) R01- or similar grant; and 20 (6%) mixed sources. Table 1 shows relevant trial characteristics of the consent forms based on funding source.

Table 1:

Associations between Characteristics of Consent Forms and Funding Source

| Pharmaceutical-funded | NCTN | R01-funded or similar non-government grant | Mixed Funding Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 106 (34) | 145 (46) | 44 (14) | 20 (6) | 315 | ||

| Phase of Trial | ||||||

| I | 48 (45) | 10 (7) | 14 (32) | 8 (40) | 80 (26) | <0.0001** |

| II | 32 (30) | 84 (58) | 26 (59) | 7 (35) | 149 (47) | |

| III | 19 (18) | 47 (32) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) | 69 (22) | |

| Missing | 7 (7) | 4 (3) | 4 (9) | 2 (10) | 17 (5) | |

| Year Trial Opened | ||||||

| 2004 | 14 (13) | 27 (19) | 9 (20) | 6 (30) | 56 (18) | 0.38*** |

| 2005 | 11 (10) | 25 (17) | 7 (16) | 4 (20) | 47 (15) | |

| 2006 | 9 (8) | 23 (16) | 3 (7) | 1 (5) | 36 (11) | |

| 2007 | 20 (19) | 19 (13) | 5 (12) | 2 (10) | 46 (15) | |

| 2008 | 22 (21) | 21 (14) | 11 (25) | 2 (10) | 56 (18) | |

| 2009 | 26 (25) | 27 (19) | 9 (20) | 4 (20) | 66 (21) | |

| 2010 | 4 (4) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 8 (2) | |

| Accrual goal met? | ||||||

| Yes | 52 (49) | 31 (21) | 5 (11) | 7 (35) | 95 (30) | 001** |

| No | 35 (33) | 24 (17) | 18 (41) | 5 (25) | 82 (26) | |

| Missing | 19 (18) | 90 (62) | 21 (48) | 8 (40) | 138 (44) | |

Missing data were excluded from analyses.

Chi-square test

Fisher’s Exact test

Consent Form Word Counts.

The median word count among these 315 consent forms was 5,129 with 4,226 words in the 25th percentile and 6,695 words in the 75th percentile. The median breakdown of word count (IQR) was 5648 (4814, 6803); 5243 (4139, 6932); 4365 (3806, 5124); and 4319 (3862, 5944) in pharmaceutical company, NCTN, R01 or similar grant, and mixed source trial consent forms, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Consent Form Word Count and Trial Funding Source.

Pharmaceutical company consent forms were the wordiest. (Kruskal-Wallis test showed significant differences in word counts in consent forms based on funding source (p<0.0001). The pairwise multiple comparison analysis using Dwass, Steel, Critchlow-Fligner Method showed significant differences in word counts in consent forms from NCTN- and R01/similar-sponsored trials (p<0.01); pharmaceutical- and R01/similar-sponsored trials (p<0.0001); and pharmaceutical-and mixed funding source-sponsored trials (p=0.01). All other pairwise comparisons were not statistically different.)

Word Count Based on Trial Characteristics.

Differences in median word counts were observed based on trial characteristics. In particular, consent forms from pharmaceutical-funded trials had higher median word counts than those funded by an R01 or similar source (p<0.0001). Pharmaceutical-funded trials also had higher median word counts than those from mixed funding sources (p=0.01). In contrast, the median word counts between pharmaceutical- and NCTN-sponsored trials were not significantly different (p =0.2) (Figure 1).

In addition, word counts were higher among NCTN-sponsored trials and those funded by R01 grants/similar sources (p<0.01). In contrast, word counts between NCTN-sponsored and mixed funding source trials (p=0.36) and between R01/similar source and mixed funding source trials (p=0.96) were not statistically different (Figure 1).

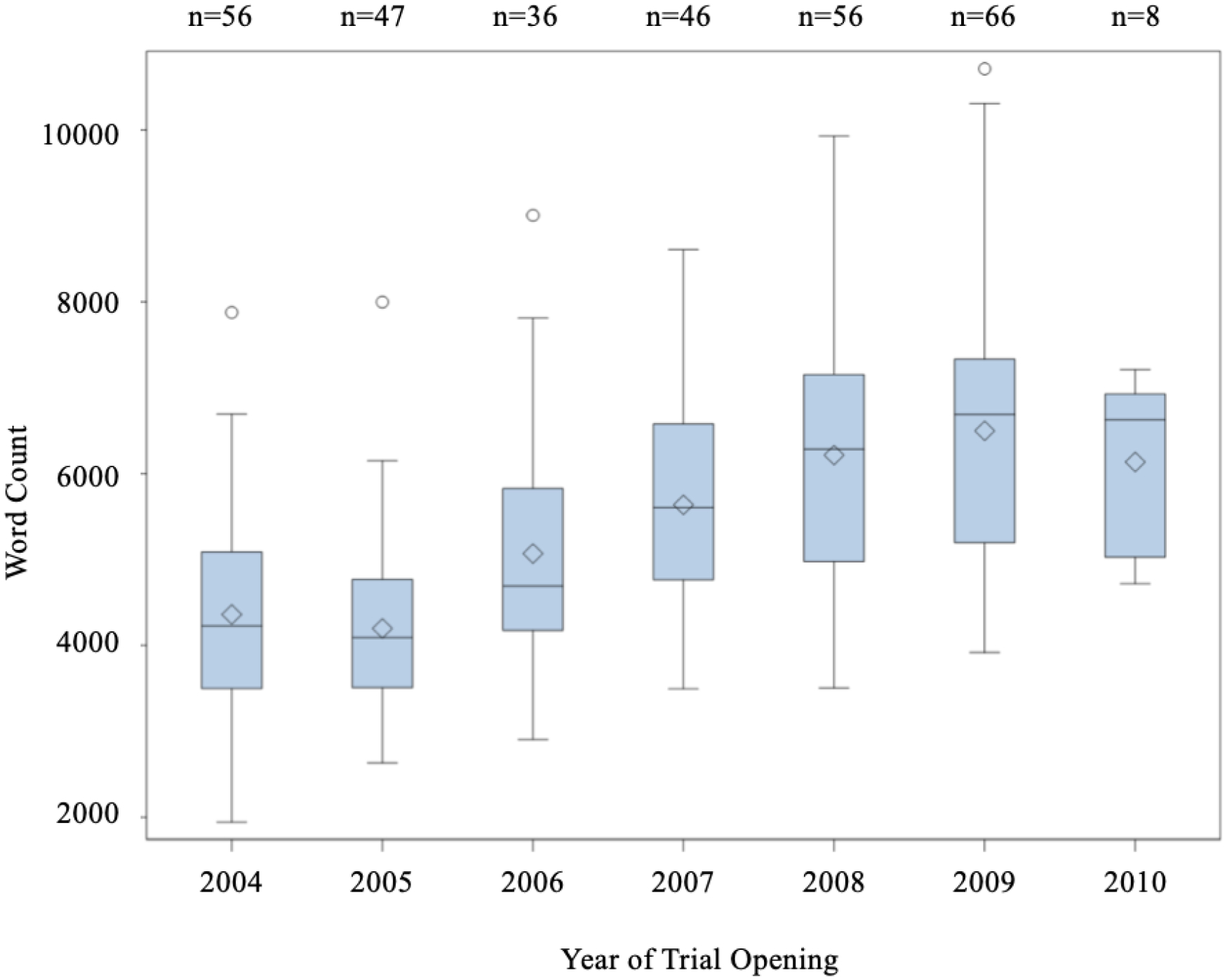

Other characteristics associated with longer word counts included phase of trial (p<0.0001). Phase III trials had the highest median word count (phase I=5424, phase II=4634, and phase III=6138). Pairwise comparisons based on phase of trials showed the following: I versus II (p< 0.01); I versus III (p= 0.02); II versus III (p <0.0001) (Figure 2). Similarly, the year of trial opening was associated with wordier consent forms with more recent trials being wordier (p<0.0001) (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Consent Form Word Count and Phase of Trial.

Phase III trials had the wordiest consent forms. (Kruskal-Wallis test showed a significant difference among phase of trial (p<0.0001). The pairwise multiple comparison analysis using Dwass, Steel, Critchlow-Fligner Method showed a significant difference between each phase of trial (I versus II (p< 0.01); I versus III (p= 0.02); II versus III (p <0.0001).)

Figure 3: Consent Form Length and the Year of Trial Opening.

Consent form wordiness increased over the span of 7 years. (Kruskal-Wallis test showed a significant annual increase (p<0.0001). Jonckheere-Terpstra Test showed significant ordered differences of median word count over the years (p<0.0001).)

Among the 95 trials that met their accrual goal, the median word count was 5931 (IQR: 4769, 7024). The median word count between trials that achieved their accrual goal (5931) and did not (5894) was not statistically different (p= 0.75); (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Word Count and Whether Trial Accrual Goal Was Reached.

No significant difference in median word count was observed between trials that met and did not meet their accrual goals (p= 0.75; Mann Whitney U test).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the word counts in consent forms for cancer clinical trials and found that pharmaceutical-sponsored trials had wordier consent forms. Furthermore, factors, such as phase of trial and date of trial opening, were also associated with word counts. To our knowledge, the current study is the largest and most temporally robust, including 300+ consent forms, spanning 7 years of trials, and incorporating 8 years of follow up to assess the impact of consent form length on achievement of trial accrual goals [8, 9]. Because the testing of new cancer drugs is currently at an all-time high and because pharmaceutical companies are sponsoring a large proportion of these clinical trials, our finding of increasing verbosity in pharmaceutical trials is especially noteworthy.

This work is timely. A recent study from Microsoft Corporation suggests that attention spans have shrunk over the past 15 years [9]. Although other sources have questioned the validity of the Microsoft Corporation study, the fact remains that patients with cancer are vulnerable and should be receiving information in a succinct and organized manner. In a recent study that examined cancer patients’ understanding of the purpose of a phase I cancer clinical trial, Hlubocky and others observed that fewer than 45% had understood the purpose of the trial presented to them, and older patients were particularly at risk for misunderstanding with only 30% having expressed accurate understanding [10]. Such findings showcase the importance of ensuring that all cancer clinical trial consent forms -- regardless of phase of trial or trial funding source – are succinct and to the point for purposes of enhancing the comprehension and understanding of patients with cancer.

The current study has limitations. First, as a single institution study, we focused only on trials that had opened at our own institution, thus narrowing the scope of this work. This design element was intentional because, as a single institution study, a single IRB reviewed and approved all these consent forms, thereby reducing the variability factor imposed by IRB’s from multiple institutions. Nonetheless, despite the single-institution nature of this project, it should be noted that we captured a wide variety of trials and report here what is perhaps the largest study to date on this topic. Second, we acknowledge the absence of some data elements. For example, although we examined achievement of accrual goals, only 30% of trials in this study had met their goal; for national phase III trials, this percentage is higher [11]. Future studies might choose to reexamine whether consent form length impacts trial accrual. Similarly, other data elements, such as the number of arms of a trial, the requirement for tumor biopsies, complexity of treatment intervention and other specific trial-related factors should also be explored to assess whether they are associated with consent form wordiness as well as trial completion. Finally, another limitation is that our study did not include the perspective of patients. Future research in this area should consider capturing and reporting the perspective of patients [10, 12, 13].

In summary, the wordiness of consent forms is an important issue that appears to be driven by many factors, including the funding source of the clinical trial. Limiting the verbosity of cancer clinical trial consent forms promises to make consent forms a more effective educational tool. It therefore behooves all researchers involved in cancer clinical trials to ensure consent forms are concise and understandable for patients and their families.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by K12CA090628.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Hochhauser M Consent Forms in Context: How Long is Long? In: SOCRA. Last accessed November 23, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barron D The New Era of Informed Consent In: Eye for Pharma. Last accessed January 20, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.FDA Drug Approvals Jump In 2004 In: Relias Media. Last accessed December 13, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 4.de le Mora-Molina H, Barajas-Ochoa A, Sandoval-Garcia L, Navarrete-Lorenzon M, Castaneda-Barragan EA, Castillo-Ortiz JD, Aceves-Avila FJ, Yanez J, Bustamante-Montes LP, Ramos-Remus C (2018) Trends of informed consent forms for industry-sponsored clinical trials in rheumatology over a 17-year period: Readability and assessment of patients’ health literacy and perceptions. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 48:547–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas CE, Michael FA (1991) On distribution-free multiple comparisons in the one-way analysis of variance. Communications in Statistics – Theory and Methods 20:127–139 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jonckheere AR (1954) A distribution-free k-sample test against ordered alternatives. Biometrika 41:133–145 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann HB, Whitney DR (1947) On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 18:50–60 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schumacher A, Sikov WM, Quesenberry M, Safran H, Khurshid H, Mitchell KM, Olszewski AJ (2017) Informed consent in oncology clinical trials: A Brown University Oncology Research Group prospective cross-sectional pilot study. PLoS One 12:e0172957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mcspadden K (2015) You Now Have a Shorter Attention Span Than a Goldfish In: TIME. Accessed 13 December 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hlubocky FJ, Sachs GA, Larson ER, Nimeiri HS, Cella D, Wroblewski KE, Ratain MJ, Peppercorn JM, Daugherty CK (2018) Do patients with advanced cancer have the ability to make informed decisions for participation in phase I clinical trials? J Clin Oncol 36:2483–2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroen TA, Petronic RG, Wang H (2010) Preliminary evaluation of factors associated with premature trial closure and feasibility of accrual benchmarks in phase 3 oncology trials. Clinical Trials, 7:312–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hlubocky FJ, Kass NE, Roter D, Larson S, Wroblewski KE, Sugarman J, Daugherty CK (2018) Investigator disclosure and advanced cancer patient understanding of informed consent and prognosis in phase I clinical trials. J Oncol Pract 14:e357–e367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett SB, Koenig CJ, Trupin L, Hlubocky FJ, Daugherty CK, Reinert A, Munster P, Dohan D (2017) What advanced cancer patients with limited treatment options know about clinical research: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 25:3235–3242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]