Abstract

Introduction

Despite the essential utility of opioids for the clinical management of pain, opioid-induced constipation (OIC) remains an important obstacle in clinical practice. In patients, OIC hinders treatment compliance and has negative effects on quality of life. From a clinician perspective, the diagnosis and management of OIC are hampered by the absence of a clear, universal diagnostic definition across disciplines and a lack of standardization in OIC treatment and assessment.

Methods

A multidisciplinary panel of physician experts who treat OIC was assembled to identify a list of ten corrective actions—five “things to do” and five “things not to do”—for the diagnosis and management of OIC, utilizing the Choosing Wisely methodology.

Results

The final list of corrective actions to improve the diagnosis and clinical management of OIC emphasized a need for: (i) better physician and patient education regarding OIC; (ii) systematic use of diagnostically validated approaches to OIC diagnosis and assessment (i.e., Rome IV criteria and Bristol Stool Scale, respectively) across various medical contexts; and (iii) awareness about appropriate, evidence-based treatments for OIC including available peripheral mu-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs).

Conclusions

Physicians who prescribe long-term opioids should be forthcoming with patients about the possibility of OIC and be adequately versed in the most recent guideline recommendations for its management.

Keywords: Bristol Stool Scale, Chronic constipation, Opioid-induced constipation, Peripheral mu-opioid receptor antagonist, Rome IV criteria

Key Summary Points

| Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is an important barrier to treatment compliance and satisfaction. |

| The diagnostic definition of OIC varies across disciplines and accordingly there is a lack of standardization in its detection and management. |

| Here, we assembled a multidisciplinary expert physician panel to identify ten corrective actions for the diagnosis and management of OIC using the Choosing Wisely methodology. |

| Panel discussion underscored a need for better education of both physicians and patients regarding OIC and improved awareness about evidence-based treatments such as peripheral mu-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs). |

| Systematic use of the Rome IV criteria and the Bristol Stool Scale can improve the detection and assessment of OIC symptoms, respectively. |

| All physicians who prescribe a long-term opioid should be forthcoming with patients about the possibility of OIC and be familiar with current guideline recommendations for its management. |

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.12855053.

Introduction

Opioids have essential value for the management of pain in a variety of patient care settings, but are simultaneously associated with a number of unpleasant adverse effects that can diminish quality of life (QoL) and hamper patient compliance with therapy [1]. Gastrointestinal events such as bloating, nausea, and constipation are frequent complaints of opioid therapy due to the expression of mu- and delta-opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract, including the myenteric plexus (Auerbach’s plexus), which regulates gut motility, and the submucosal plexus (Meissner’s plexus), which is responsible for the secretion and absorption of water and electrolytes [2, 3]. Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is the most common type of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction, occurring in 47–94% of patients receiving opioids for cancer pain [4, 5] and 41–57% of patients for chronic non-cancer pain [1, 6]. While OIC is understudied in a context of dependence, recent reports indicate that 60–90% of patients receiving opioid substitution therapy experience gastrointestinal symptoms and associated decreases in QoL, but only a small proportion of these individuals seek healthcare for their constipation symptoms [7, 8].

Despite its prevalence, OIC remains underdiagnosed and undertreated in a large proportion of patients [3]. A nationwide study in France demonstrated that among 414 participants with OIC, only 43% had been prescribed a medication to treat their symptoms (most commonly an osmotic laxative) and treatment satisfaction was only moderate [9]. Moreover, 50–80% of individuals taking a laxative for OIC describe only a limited improvement in symptoms [10, 11], and a multinational survey in Europe found that 20% of patients were dissatisfied with their currently prescribed OIC regimen [3]. Deficits in the detection and management of OIC are significantly related to the absence of a consensus definition for OIC as well as the shortcomings of previous recommendations that were largely based on anecdotal evidence or expert opinion [12]. In recent years, pharmaceutical development for OIC has permitted substantial research into its pharmacological management such as with peripheral mu-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs), leading to the publication of updated guidelines from the American Society of Addiction Medicine [13] and subsequently a recent expert consensus in Europe [14]. Nonetheless, evidence of low guideline compliance by physicians and patient dissatisfaction indicate a need to assess the current state of OIC diagnosis and management and identify potential corrective actions to bring current practices into compliance with updated recommendations. Using the Choosing Wisely methodology, an expert panel was assembled and tasked with generating a list of ten corrective actions including five “things to do” and five “things not to do” in the detection and management of OIC (Table 1). This study was not subject to approval by a local ethics committee. The research was based on author (physician) experience and on previously conducted studies and does not include new research with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Table 1.

“Things to do” and “things not to do” in the diagnosis and management of OIC

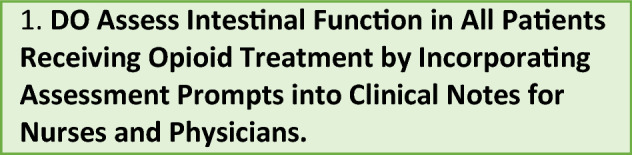

| 1. DO assess intestinal function in all patients receiving long-term (> 1 month) opioid treatment. Assessments should be incorporated into clinical or nurse notes about the patient using standardized parameters for OIC assessment |

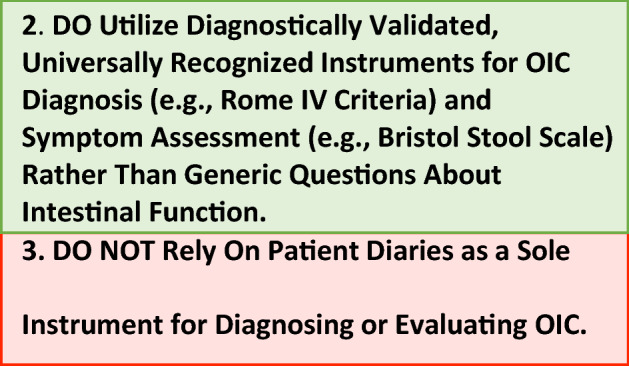

| 2. DO utilize diagnostically validated, universally recognized instruments for OIC diagnosis (e.g., Rome IV criteria) and symptom assessment (e.g., Bristol Stool Scale) rather than generic questions about intestinal function |

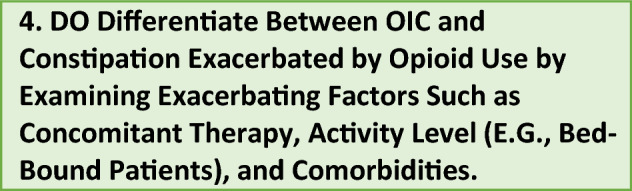

| 3. DO differentiate between OIC and opioid-exacerbated constipation (OEC) by examining exacerbating factors such as concomitant therapy, activity level (e.g., bed-bound patients), and comorbidities |

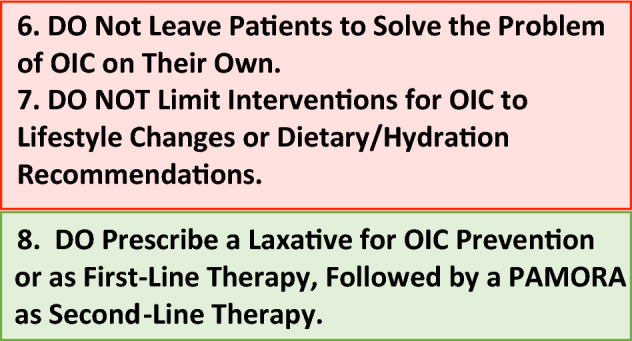

| 4. DO prescribe a laxative for OIC prevention or as first-line therapy, followed by a PAMORA as second-line therapy |

| 5. DO ensure proper education about OIC. Physicians of all specialties who treat patients on a long-term opioid, nurses, caregivers, and patients should be instructed about the risks of OIC and strategies for its prevention or treatment |

| 1. DO NOT rely on patient diaries as a sole instrument for diagnosing or evaluating OIC |

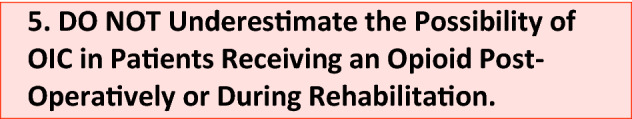

| 2. DO NOT underestimate the possibility of OIC in patients receiving an opioid post-operatively or during rehabilitation |

| 3. DO NOT leave patients to solve the problem of OIC on their own |

| 4. DO NOT limit interventions for OIC to lifestyle changes or dietary/hydration recommendations |

| 5. DO NOT modify existing opioid therapy as a preventive or therapeutic strategy for OIC at the risk of compromising patient analgesia |

Diagnosis and Assessment

Among the deficits in clinical practice with regard to OIC, discussed by the panel, a main theme that emerged was a need for physicians to take a more active role in OIC detection. In clinical practice, it is common (across care settings) for physicians to leave the subject of OIC unaddressed until a patient or caregiver specifically denotes the development of constipation symptoms. As outlined in the introduction, the prevalence of OIC among individuals who use opioids is high (41–87%) [1, 4–7], regardless of treatment purpose. One study indicated that patients were equally bothered by constipation from weak and strong opioids, despite a lower severity of physical symptoms and effect on QoL associated with the former [3]. It is also noteworthy that, unlike other common opioid complaints, such as nausea and drowsiness, OIC is not subject to tolerance; therefore, constipation symptoms are unlikely to resolve on their own with time [15]. For these reasons, constipation should be evaluated on a continuous basis in all patients who take an opioid. Available guidelines do not provide a clear recommendation as to the frequency with which OIC should be evaluated [13, 14]. To this end, the panel agreed that OIC should not be assessed episodically, but rather continuously, similar to the way in which other symptoms such as pain are evaluated. The evaluation of OIC begins before the patient has assumed the first dose of opioid and must continue for the duration of therapy. Specifically, the panel emphasized the need to evaluate preexisting constipation or gastrointestinal irregularities before initiating opioid treatment (i.e., the possibility for opioids to exacerbate constipation; see recommendation 4); the need for regular OIC assessments incorporated into routine clinical notes, so as to provide a written prompt for assessing constipation symptoms on a continuous basis; and special attention to the emergence of OIC when opioid therapy is modified, for example a change in dosage or opioid switching. In one study, implementation of a standardized constipation management protocol in a setting of geriatric care resulted in better due diligence by staff and improved nursing documentation regarding bowel care [16].

Among the deficits in clinical practice with regard to OIC, discussed by the panel, a main theme that emerged was a need for physicians to take a more active role in OIC detection. In clinical practice, it is common (across care settings) for physicians to leave the subject of OIC unaddressed until a patient or caregiver specifically denotes the development of constipation symptoms. As outlined in the introduction, the prevalence of OIC among individuals who use opioids is high (41–87%) [1, 4–7], regardless of treatment purpose. One study indicated that patients were equally bothered by constipation from weak and strong opioids, despite a lower severity of physical symptoms and effect on QoL associated with the former [3]. It is also noteworthy that, unlike other common opioid complaints, such as nausea and drowsiness, OIC is not subject to tolerance; therefore, constipation symptoms are unlikely to resolve on their own with time [15]. For these reasons, constipation should be evaluated on a continuous basis in all patients who take an opioid. Available guidelines do not provide a clear recommendation as to the frequency with which OIC should be evaluated [13, 14]. To this end, the panel agreed that OIC should not be assessed episodically, but rather continuously, similar to the way in which other symptoms such as pain are evaluated. The evaluation of OIC begins before the patient has assumed the first dose of opioid and must continue for the duration of therapy. Specifically, the panel emphasized the need to evaluate preexisting constipation or gastrointestinal irregularities before initiating opioid treatment (i.e., the possibility for opioids to exacerbate constipation; see recommendation 4); the need for regular OIC assessments incorporated into routine clinical notes, so as to provide a written prompt for assessing constipation symptoms on a continuous basis; and special attention to the emergence of OIC when opioid therapy is modified, for example a change in dosage or opioid switching. In one study, implementation of a standardized constipation management protocol in a setting of geriatric care resulted in better due diligence by staff and improved nursing documentation regarding bowel care [16].

The diagnosis of OIC has historically been complicated by the absence of a universally accepted definition, as the exact definition of OIC differs across medical specialties and clinical studies [17]. In the panel discussion, it was noted that many physicians rely on patient diaries (i.e., self-report) for the detection and diagnosis of OIC. While useful to some degree, this tool is subject to patient as well as physician bias if a diagnosis is made without ensuring that specific criteria have been met. Diary and self-report measures are particularly vulnerable to confounding in patients with bowel obsessive syndrome or compulsion disorders related to defecation, which are common in the elderly and in patients with a history of chronic constipation [18]. Conversely, panel physicians also expressed that patients receiving substitution therapy for opioid dependence were likely to underreport constipation symptoms, consistent with literature observations [7]. For this reason, the panel emphasized that the use of diaries as a sole instrument for diagnosing or evaluating OIC is a definitive “not to do.” Rather, a critical “to do” recommendation was to standardize use of the Rome IV criteria [19, 20] for diagnosing OIC, regardless of physician discipline or treatment context. Diagnostic use of these criteria is supported by recent literature demonstrating an apparent correlation with symptomatic and biopsychosocial burden from constipation [3]. With regard to following OIC symptoms, especially for the monitoring of treatment response, the Bowel Function Index (BFI) and Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) are both useful for continuous monitoring of OIC symptoms; however, the BSFS was ultimately advocated by the expert panel based on its ease of use by patients [2] and compatibility with the Rome IV criteria (i.e., the use of BSFS grading to determine whether a patient is eligible for a diagnosis of constipation) [14]. Lastly, the panel noted that assessment tools are most effective when implemented progressively. Progressive use involves establishing a baseline before initiating therapy and carefully following changes over time on a given scale to determine the emergence of OIC symptoms and responses to treatment.

The diagnosis of OIC has historically been complicated by the absence of a universally accepted definition, as the exact definition of OIC differs across medical specialties and clinical studies [17]. In the panel discussion, it was noted that many physicians rely on patient diaries (i.e., self-report) for the detection and diagnosis of OIC. While useful to some degree, this tool is subject to patient as well as physician bias if a diagnosis is made without ensuring that specific criteria have been met. Diary and self-report measures are particularly vulnerable to confounding in patients with bowel obsessive syndrome or compulsion disorders related to defecation, which are common in the elderly and in patients with a history of chronic constipation [18]. Conversely, panel physicians also expressed that patients receiving substitution therapy for opioid dependence were likely to underreport constipation symptoms, consistent with literature observations [7]. For this reason, the panel emphasized that the use of diaries as a sole instrument for diagnosing or evaluating OIC is a definitive “not to do.” Rather, a critical “to do” recommendation was to standardize use of the Rome IV criteria [19, 20] for diagnosing OIC, regardless of physician discipline or treatment context. Diagnostic use of these criteria is supported by recent literature demonstrating an apparent correlation with symptomatic and biopsychosocial burden from constipation [3]. With regard to following OIC symptoms, especially for the monitoring of treatment response, the Bowel Function Index (BFI) and Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) are both useful for continuous monitoring of OIC symptoms; however, the BSFS was ultimately advocated by the expert panel based on its ease of use by patients [2] and compatibility with the Rome IV criteria (i.e., the use of BSFS grading to determine whether a patient is eligible for a diagnosis of constipation) [14]. Lastly, the panel noted that assessment tools are most effective when implemented progressively. Progressive use involves establishing a baseline before initiating therapy and carefully following changes over time on a given scale to determine the emergence of OIC symptoms and responses to treatment.

An important consideration highlighted by the panel was the importance of differentiating between OIC and opioid-exacerbated constipation (OEC). Differentiating OEC from OIC can lead to solutions that do not necessarily involve modifying opioid therapy, thereby preserving the current level of patient analgesia. For example, opioids can exacerbate constipation associated with the use of antidepressants, antihistamines, antiepileptic agents, diuretics, and calcium antagonists. In patients undergoing cancer treatment, opioids can exacerbate preexisting constipation related to antiemetic medications such as 5-HT3 antagonists and NK1 antagonists. Indeed, prescribed medications are a common factor contributing to chronic constipation in the literature [21]. Patient comorbidities should also be considered as potential exacerbating factors: for example, hypothyroidism or a history of chronic constipation or other gastrointestinal disturbance. A thorough differential diagnosis should exclude comorbidities that can potentially cause or exacerbate constipation or defecation, such as obstructive colon cancer or other bowel obstructions, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, or other underlying conditions such as dyssynergic defecation or large rectocele [22]. In some patients (especially those receiving palliative care), immobility, long-term bed restriction, and dehydration or dietary restrictions are significant contributing factors to chronic constipation; as patients become weaker, they may resort to defecating in non-physiologic positions, further exacerbating constipation symptoms [2]. Available guidelines advocate a thorough patient medical history and inquiring about constipation symptoms prior to initiation of an opioid regimen [13, 14]. This effort is necessary to facilitate quick action upon the appearance of OIC symptoms and optimal management.

An important consideration highlighted by the panel was the importance of differentiating between OIC and opioid-exacerbated constipation (OEC). Differentiating OEC from OIC can lead to solutions that do not necessarily involve modifying opioid therapy, thereby preserving the current level of patient analgesia. For example, opioids can exacerbate constipation associated with the use of antidepressants, antihistamines, antiepileptic agents, diuretics, and calcium antagonists. In patients undergoing cancer treatment, opioids can exacerbate preexisting constipation related to antiemetic medications such as 5-HT3 antagonists and NK1 antagonists. Indeed, prescribed medications are a common factor contributing to chronic constipation in the literature [21]. Patient comorbidities should also be considered as potential exacerbating factors: for example, hypothyroidism or a history of chronic constipation or other gastrointestinal disturbance. A thorough differential diagnosis should exclude comorbidities that can potentially cause or exacerbate constipation or defecation, such as obstructive colon cancer or other bowel obstructions, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, or other underlying conditions such as dyssynergic defecation or large rectocele [22]. In some patients (especially those receiving palliative care), immobility, long-term bed restriction, and dehydration or dietary restrictions are significant contributing factors to chronic constipation; as patients become weaker, they may resort to defecating in non-physiologic positions, further exacerbating constipation symptoms [2]. Available guidelines advocate a thorough patient medical history and inquiring about constipation symptoms prior to initiation of an opioid regimen [13, 14]. This effort is necessary to facilitate quick action upon the appearance of OIC symptoms and optimal management.

Adequate management of postoperative pain is associated with key patient benefits such as a reduction in postoperative complications, earlier patient mobility, shorter hospital stays, and improved rehabilitation [23]. Opioids are a critical tool for postoperative pain relief; however, constipation is an important consideration in these patients, especially when patients are required to remain immobile for significant periods after surgery or when a long-term opioid is indicated during rehabilitation. The onset of constipation can lead patients to reduce opioid doses and therefore compromise analgesia, delaying recovery. Yet, a number of factors can contribute to postoperative constipation, such as changes in diet related to hospitalization and preexisting conditions. Some literature suggests that preoperative long-term opioid use is a risk factor for long-term use after surgery and new-onset constipation [24, 25]; for this reason, physician education about OIC as part of perioperative pain management should cover strategies for challenging situations such as individuals with opioid dependence or tolerance [26, 27]. The expert panel also noted a need to distinguish OIC from general post-surgical constipation to avoid unnecessary discontinuation of effective pain therapy and improve patient outcomes.

Adequate management of postoperative pain is associated with key patient benefits such as a reduction in postoperative complications, earlier patient mobility, shorter hospital stays, and improved rehabilitation [23]. Opioids are a critical tool for postoperative pain relief; however, constipation is an important consideration in these patients, especially when patients are required to remain immobile for significant periods after surgery or when a long-term opioid is indicated during rehabilitation. The onset of constipation can lead patients to reduce opioid doses and therefore compromise analgesia, delaying recovery. Yet, a number of factors can contribute to postoperative constipation, such as changes in diet related to hospitalization and preexisting conditions. Some literature suggests that preoperative long-term opioid use is a risk factor for long-term use after surgery and new-onset constipation [24, 25]; for this reason, physician education about OIC as part of perioperative pain management should cover strategies for challenging situations such as individuals with opioid dependence or tolerance [26, 27]. The expert panel also noted a need to distinguish OIC from general post-surgical constipation to avoid unnecessary discontinuation of effective pain therapy and improve patient outcomes.

Prevention and Treatment

In line with a focus on physicians taking a more active stance regarding OIC detection, the panel similarly underscored the importance of an active stance in prevention and treatment. Prevention strategies should be implemented in all patients who may potentially experience OIC and these strategies should consider the unique challenges associated with each patient group: cancer pain, chronic non-cancer pain, palliative care, and patients in substitution therapy for opioid dependence. To this end, the panel underscored a need to consider the latter group (patients in substitution therapy), as OIC prevention is often overlooked in these individuals because of stigma or the perception that preventing constipation is not a treatment priority.

In line with a focus on physicians taking a more active stance regarding OIC detection, the panel similarly underscored the importance of an active stance in prevention and treatment. Prevention strategies should be implemented in all patients who may potentially experience OIC and these strategies should consider the unique challenges associated with each patient group: cancer pain, chronic non-cancer pain, palliative care, and patients in substitution therapy for opioid dependence. To this end, the panel underscored a need to consider the latter group (patients in substitution therapy), as OIC prevention is often overlooked in these individuals because of stigma or the perception that preventing constipation is not a treatment priority.

Above all else, patients should not be left alone to anticipate or resolve the issue of OIC; in one study, patients who were unsatisfied with physician-mandated constipation management resorted to suboptimal strategies such as reducing their opioid dose or other forms of treatment noncompliance in order to alleviate constipation [3]. It is critical that physicians not assume that the issue of constipation is the responsibility of another healthcare provider such as another specialist or nurse. Moreover, while important, offering advice about lifestyle (e.g., activity level, diet, and hydration) does not constitute a complete strategy for OIC prevention or treatment. Physicians should take full advantage of available laxative and pharmacological tools for the prophylaxis and treatment of OIC. The recently published European consensus on the management of OIC recommends first-line treatment of OIC with standard laxatives such as osmotic agents (macrogol) and stimulants (bisacodyl, senna) [14]. Panel consensus was congruent with this recommendation: laxatives can be offered at the initiation of opioid treatment for prevention or should otherwise be prescribed for the emergence of constipation symptoms. That said, the efficacy of laxatives for OIC is controversial in some studies indicating low patient satisfaction and the persistence of OIC despite continued laxative treatment [28, 29]. This is likely to due to the fact that laxatives do not specifically target the mechanism of action that causes OIC, i.e., opioid receptors expressed in the gastrointestinal tract.

Oral opioid–naloxone combined formulations are a useful pharmacological tool for OIC prevention and treatment [30], as the extensive first pass hepatic metabolism of naloxone restricts active drug to the gastrointestinal tract [31]. Naloxone-containing opioid formulations are useful in opioid-naïve patients with preexisting abdominal issues who necessitate opioid therapy. A critical limitation, however, is that these combinations require fixed opioid dosing and are typically only available with oxycodone.

PAMORAs are recommended as second-line therapy due to their peripherally restricted and direct action at opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract [13, 14]. These agents are an attractive option for OIC as they target the cause of constipation symptoms (i.e., opioid receptors). Naldemedine, naloxegol, and methylnaltrexone are three common PAMORAs that have demonstrated good efficacy for the management of OIC but continue to be underutilized by clinicians [32]. A recent meta-analysis of available medications for OIC highlighted a body of evidence supporting the use of these three agents to treat OIC in chronic non-cancer pain [33]. In Italy, these medications are indicated for the treatment of OIC in all patients receiving long-term opioid therapy [34]. Methylnaltrexone is administered by subcutaneous injection and therefore has limited application for OIC given the invasive nature of treatment [35], whereas naloxegol and naldemedine are available in once-daily oral formulations and therefore have broader utility for the treatment of OIC [36, 37]. In placebo-controlled phase III studies (COMPOSE-4 and COMPOSE-5), naldemedine improved the number of spontaneous bowel movements and produced corresponding increases in QoL without influencing opioid analgesia or producing symptoms of opioid withdrawal among individuals with OIC who were taking an opioid for cancer pain [38, 39]. Similar findings were obtained in phase III studies conducted in patients with OIC taking an opioid for chronic non-cancer pain [40]. At present, no study has performed a prospective comparison of naldemedine to naloxegol or methylnaltrexone. PAMORAs have not demonstrated significant efficacy for OIC prevention, but physicians should be aware of their excellent utility and tolerability for OIC management [41]. Physicians should however pay careful attention to the use of PAMORAs in patients with abdominal cancer or complete or partial bowel obstruction due to the risk of precipitating cramps or colicky pain [32, 42].

OIC has a profound negative influence on patient QoL [43]; however, in patients taking an opioid for pain, it is important to acknowledge that both OIC and underlying pain are factors that reduce QoL [1, 44]. Therefore, constipation symptoms and underlying pain should be equally considered when evaluating possible solutions to improve patient QoL. Consistent with this notion and existing recommendations [14], the expert panel emphasized that the level of analgesia should never be sacrificed as a solution for OIC. Rather, physicians should follow recommendations about the use of laxatives and second-line therapies such as PAMORAs in order to support all aspects of patient QoL. It is also important to note that OIC is not necessarily dose-dependent and can vary by opioid type or formulation, as well as across individuals based on patient clinical history and pharmacogenetic variation. To this end, dose reduction without considering other strategies for constipation relief (e.g., exacerbating factors, adding a PAMORA) is a poor solution that risks worsening the patient’s condition and decreasing analgesia without any benefit for constipation symptoms.

OIC has a profound negative influence on patient QoL [43]; however, in patients taking an opioid for pain, it is important to acknowledge that both OIC and underlying pain are factors that reduce QoL [1, 44]. Therefore, constipation symptoms and underlying pain should be equally considered when evaluating possible solutions to improve patient QoL. Consistent with this notion and existing recommendations [14], the expert panel emphasized that the level of analgesia should never be sacrificed as a solution for OIC. Rather, physicians should follow recommendations about the use of laxatives and second-line therapies such as PAMORAs in order to support all aspects of patient QoL. It is also important to note that OIC is not necessarily dose-dependent and can vary by opioid type or formulation, as well as across individuals based on patient clinical history and pharmacogenetic variation. To this end, dose reduction without considering other strategies for constipation relief (e.g., exacerbating factors, adding a PAMORA) is a poor solution that risks worsening the patient’s condition and decreasing analgesia without any benefit for constipation symptoms.

OIC Awareness and Education

Finally, discussion amongst the expert panel continuously returned to the topic of awareness and health care professionals’ preparation. As per the panel, physicians are generally interested in the topic of OIC but often do not receive adequate education about it. It is also noteworthy that a lack of physician preparation regarding OIC is at least in part related to a lack of consensus or standardization in the approach to OIC management across disciplines, reflecting the importance of the recommendations provided by this multidisciplinary panel discussion. As a prime example, panel members expressed that while physicians were at times aware of the availability of PAMORAs, they did not feel equipped to use them in daily clinical practice and lacked information about key side effects or advantages over traditional laxative regimens. Many healthcare professionals including physicians are not sufficiently trained regarding the use of opioids in general or the management of related adverse effects [45]. Accordingly, some changes to education regarding opioid prescription and management as well as awareness campaigns targeting healthcare professionals to this end are ultimately needed. This guidance is applicable to all physicians who prescribe opioids and any healthcare professionals who see patients who receive long-term opioid therapy.

Finally, discussion amongst the expert panel continuously returned to the topic of awareness and health care professionals’ preparation. As per the panel, physicians are generally interested in the topic of OIC but often do not receive adequate education about it. It is also noteworthy that a lack of physician preparation regarding OIC is at least in part related to a lack of consensus or standardization in the approach to OIC management across disciplines, reflecting the importance of the recommendations provided by this multidisciplinary panel discussion. As a prime example, panel members expressed that while physicians were at times aware of the availability of PAMORAs, they did not feel equipped to use them in daily clinical practice and lacked information about key side effects or advantages over traditional laxative regimens. Many healthcare professionals including physicians are not sufficiently trained regarding the use of opioids in general or the management of related adverse effects [45]. Accordingly, some changes to education regarding opioid prescription and management as well as awareness campaigns targeting healthcare professionals to this end are ultimately needed. This guidance is applicable to all physicians who prescribe opioids and any healthcare professionals who see patients who receive long-term opioid therapy.

Another deficit in healthcare professional preparation relates to the use of standardized instruments in clinical practice. The present recommendations of our panel propose use of the Rome IV and BSFS for OIC diagnosis and evaluation, respectively; however, appropriate application of these instruments and a degree of physician experience is necessary to ensure maximal objectivity. Therefore, campaigns or educational sessions that target physicians and other healthcare professionals should train these professionals about application of these scales in clinical practice.

From a patient perspective, a previous multinational survey of five European countries reported that nearly 60% of healthcare professionals failed to adequately inform patients about constipation as a common side effect of opioid use [3]. Adequate preparation and information sharing are critical for fostering positive patient–provider interactions (especially in a context of chronic pain management) and collaborative treatment decision-making [46]. Therefore, the panel emphasized the need for physicians to adequately inform patients as to the risks and benefits of opioid consumption prior to initiating therapy; utilize strategies such as brochures or awareness campaigns to teach patients how to recognize and report the onset of symptoms; and encourage patients to be more forthcoming in their communication with healthcare professionals, making them collaborative participants in their own care.

Limitations

The present study had some limitations. In particular, the panel discussion did not cover the use of general, wide-reaching educational programs designed to increase the knowledge of healthcare professionals about the prevention and management of OIC. Standardization of this topic is extremely urgent for improving the clinical management of OIC. Although the effects of educational programs are visible on a timescale of years, early implementation is crucial for problem resolution, especially to make professionals aware about the availability of OIC solutions when the health care system has made available any means to obtain the solution of the OIC, including PAMORAs. For this reason, a future panel discussion is recommended to propose a standardized educational program about OIC awareness, prevention, and therapy for healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current state of OIC diagnosis and management remains inadequate but is bolstered by apparent physician interest in improving the standard of care in patients who take a long-term opioid. Here we propose a simple set of corrective actions that can assist physicians across a variety of disciplines in standardizing OIC detection and enacting timely, evidence-based treatment. Furthermore, physicians should note that appropriate management of OIC can necessitate the skills and competence of specialists depending on the specific medical history of the patient and the nature of opioid use; for example, multidisciplinary management of OIC should involve pain or addiction specialists for patients with chronic pain, anesthesiologists for patients with postoperative pain, and oncologists or palliative care specialists for patients with advanced cancers. Future efforts should focus on educating physicians about how and when to involve these specialists; how to use the proposed diagnostic, assessment, and treatment tools available to them for OIC; and how to better inform patients about OIC and its treatment options so that patients can ultimately collaborate in their own care.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee was provided by Shionogi Inc. and Molteni Farmaceutici.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors would like to thank Claudia Laterza, MD of Sanitanova S.r.l. and Ashley Symons, PhD for draft preparation and editorial assistance. This assistance was funded by Shionogi Inc. and Molteni Farmaceutici.

Disclosures

Domenico Alvaro has received research grants and consultant fees from Intercept Pharma, Molteni, Shionogi, Vesta and is a consultant for Aboca. Augusto Tommaso Caraceni has received research grants and other funding from Molteni, Gruenenthal GmbH, Prokstrakan, Amgen, and Ipsen and is a consultant for Kyowa Kirin, Gruenenthal GmbH, Pfizer, Helsin Healthcare, Molteni, Shionogi, Italfarmaco, Sandoz International GmbH, and the Institute de Recherche “Pierre Fabre.” Flaminia Coluzzi is speaker and consultant for Angelini, Grunenthal, Malesci, Molteni, Pfizer, Shionogi. Walter Gianni, Fabio Lugoboni, Franco Mariangeli, Giuseppe Massazza, Carmine Pinto, and Giustino Varrassi have received research grants and other funding from Molteni and Shionogi. Giustino Varrassi is also a member of the Advisor Boards of Abbott, Dompé, Malesci, Menarini International, Molteni, Mundipharma, Shionogi. He is also Member of the Speakers’ Bureau of Berlin-Chemie, Dompé, MAP, Menarini International, MCAC, Molteni, Takeda. He has received funds for research by Dompé, Fondazione Maugeri, and Pfizer, and he is Editor-in-Chief of Pain and Therapy.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was not subject to approval by a local ethics committee. The research was based on author (physician) experience and on previously conducted studies and does not include new research with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: One of the author names, Franco Marinangeli, was incorrectly published in the original article. It has been now corrected.

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.12855053.

Change history

10/20/2020

The original article can be found online.

References

- 1.Bell T, Annunziata K, Leslie JB. Opioid-induced constipation negatively impacts pain management, productivity, and health-related quality of life: findings from the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5(3):137–144. doi: 10.5055/jom.2009.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sizar O, Gupta M. Opioid Induced constipation. Treasure Island: StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andresen V, Banerji V, Hall G, et al. The patient burden of opioid-induced constipation: new insights from a large, multinational survey in five European countries. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(8):1254–1266. doi: 10.1177/2050640618786145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glare P, Walsh D, Sheehan D. The adverse effects of morphine: a prospective survey of common symptoms during repeated dosing for chronic cancer pain. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23(3):229–235. doi: 10.1177/1049909106289068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drewes AM, Munkholm P, Simren M, et al. Definition, diagnosis and treatment strategies for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction-Recommendations of the Nordic Working Group. Scand J Pain. 2016;11:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuteja AK, Biskupiak J, Stoddard GJ, et al. Opioid-induced bowel disorders and narcotic bowel syndrome in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(4):424–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Troberg K, Hakansson A, Dahlman D. Self-rated physical health and unmet healthcare needs among swedish patients in opioid substitution treatment. J Addict. 2019;2019:7942145. doi: 10.1155/2019/7942145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lugoboni F, Mirijello A, Zamboni L, et al. High prevalence of constipation and reduced quality of life in opioid-dependent patients treated with opioid substitution treatments. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17(16):2135–2141. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2016.1232391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ducrotte P, Milce J, Soufflet C, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of opioid-induced constipation in the general population: a French study of 15,000 individuals. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(4):588–600. doi: 10.1177/2050640616659967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook SF, Lanza L, Zhou X, et al. Gastrointestinal side effects in chronic opioid users: results from a population-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(12):1224–1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Costing statement: Naloxegol for treating opioid-induced constipation (TA345). 2015.

- 12.Brenner DM, Stern E, Cash BD. Opioid-related constipation in patients with non-cancer pain syndromes: a review of evidence-based therapies and justification for a change in nomenclature. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(3):12. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0560-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358–367. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer AD, Drewes AM, Chiarioni G, et al. Pathophysiology and management of opioid-induced constipation: European expert consensus statement. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(1):7–20. doi: 10.1177/2050640618818305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holzer P, Ahmedzai SH, Niederle N, et al. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction in cancer-related pain: causes, consequences, and a novel approach for its management. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5(3):145–151. doi: 10.5055/jom.2009.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein J, Holowaty S. Managing constipation: implementing a protocol in a geriatric rehabilitation setting. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40(8):18–27. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20140501-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaertner J, Siemens W, Camilleri M, et al. Definitions and outcome measures of clinical trials regarding opioid-induced constipation: a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(1):9–16. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cosci F. “Bowel obsession syndrome” in a patient with chronic constipation. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(4):451e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simren M, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Update on rome IV criteria for colorectal disorders: implications for clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(4):15. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0554-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What Is New in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23(2):151–163. doi: 10.5056/jnm16214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suares NC, Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(9):1582–1591. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson AD, Camilleri M. Chronic opioid induced constipation in patients with nonmalignant pain: challenges and opportunities. Thera Adv Gastroenterol. 2015;8(4):206–220. doi: 10.1177/1756283X15578608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshi GP, Kehlet H. Postoperative pain management in the era of ERAS: an overview. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2019;33(3):259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain N, Brock JL, Phillips FM, et al. Chronic preoperative opioid use is a risk factor for increased complications, resource use, and costs after cervical fusion. Spine J. 2018;18(11):1989–1998. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain N, Phillips FM, Weaver T, et al. Preoperative chronic opioid therapy: a risk factor for complications, readmission, continued opioid use and increased costs after one- and two-level posterior lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43(19):1331–1338. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coluzzi F, Bifulco F, Cuomo A, et al. The challenge of perioperative pain management in opioid-tolerant patients. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:1163–1173. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S141332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pergolizzi JV, Lequang JA, Passik S, et al. Using opioid therapy for pain in clinically challenging situations: questions for clinicians. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019;85(8):899–908. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.19.13321-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streicher JM, Bilsky EJ. Peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists for the treatment of opioid-related side effects: mechanism of action and clinical implications. J Pharm Pract. 2018;31(6):658–669. doi: 10.1177/0897190017732263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emmanuel A, Johnson M, McSkimming P, et al. Laxatives do not improve symptoms of opioid-induced constipation: results of a patient survey. Pain Med. 2017;18(10):1932–1940. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morlion B, Clemens KE, Dunlop W. Quality of life and healthcare resource in patients receiving opioids for chronic pain: a review of the place of oxycodone/naloxone. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40261-014-0254-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith K, Hopp M, Mundin G, et al. Low absolute bioavailability of oral naloxone in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;50(5):360–367. doi: 10.5414/cp201646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pergolizzi JV, Jr, Christo PJ, LeQuang JA, et al. The use of peripheral mu-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORA) in the management of opioid-induced constipation: an update on their efficacy and safety. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2020;14:1009–1025. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S221278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy JA, Sheridan EA. Evidence based review of pharmacotherapy for opioid-induced constipation in noncancer pain. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52(4):370–379. doi: 10.1177/1060028017739637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gazzetta Ufficiale della Republica Italiana Anno 161° - Numero 111 del 30 Aprile 2020.

- 35.Salix Pharmaceuticals Inc . Relistor® (methylnaltrexone bromide subcutaneous injection) Raleigh: Full Prescribing Information; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.AstraZeneca AB. Moventig® (naloxegol) Södertälje: Full Prescribing Information; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coluzzi F, Scerpa MS, Pergolizzi J. Naldemedine: a new option for OIBD. J Pain Res. 2020;13:1209–1222. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S243435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katakami N, Harada T, Murata T, et al. Randomized phase III and extension studies of naldemedine in patients with opioid-induced constipation and cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3859–3866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katakami N, Harada T, Murata T, et al. Randomized phase III and extension studies: efficacy and impacts on quality of life of naldemedine in subjects with opioid-induced constipation and cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(6):1461–1467. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saito Y, Yokota T, Arai M, et al. Naldemedine in Japanese patients with opioid-induced constipation and chronic noncancer pain: open-label Phase III studies. J Pain Res. 2019;12:127–138. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S175900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blair HA. Naldemedine: a review in opioid-induced constipation. Drugs. 2019;79(11):1241–1247. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viscusi ER. Clinical overview and considerations for the management of opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(2):174–188. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cook SF, Bell T, Sweeny CT, et al. Impact on quality of life of constipation associated GI symptoms related to opioid treatment in chronic pain patients: pAC-QoL results from the opioid survey, In: 26th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Pain Society, 2007.

- 44.Duenas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, et al. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016;9:457–467. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S105892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh R, Pushkin GW. Should medical education better prepare physicians for opioid prescribing? AMA J Ethics. 2019;21(8):E636–E641. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2019.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frantsve LM, Kerns RD. Patient-provider interactions in the management of chronic pain: current findings within the context of shared medical decision making. Pain Med. 2007;8(1):25–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.