Abstract

There is limited literature reporting the oral pathogen Parvimonas micra as the causative organism of periprosthetic joint infection. Previous reports demonstrate septic arthritis in native or prosthetic joints due to P. micra in elderly or immunocompromised patients associated with tooth abscess and periodontal disease. Our case report is unique because it describes a healthy individual with recurrent gingivitis developing periprosthetic joint infection after total knee arthroplasty as the result of isolated P. micra. Her clinical symptom presented early and manifested as progressive stiffness only. Timely aspiration resulted in early diagnosis, but the patient still underwent 2-stage revision with a more constrained implant. To prevent the risk of infection by oral pathogens such as P. micra, dental history should be thoroughly investigated, and any lingering periodontal infection should be addressed before any arthroplasty operation.

Keywords: Parvimonas micra, Peptostreptococcus micros, Periprosthetic joint infection, Total knee arthroplasty, Stiffness

Introduction

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a dreaded complication in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [1]. As the number of TKAs continue to rise, there will be a concomitant increase in PJI cases and associated morbidity and mortality [2,3]. Diagnostic algorithms and clinical guidelines have been studied and validated as tools in recognizing and minimizing PJI. However, atypical pathogens that lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment continue to challenge practitioners. More specifically, oral pathogens such as Parvimonas micra (formerly Peptostreptococcus micros) are difficult to manage because they are so infrequently reported [4]. P. micra is an oral pathogen that has been implicated in apical abscesses that can cause spondylodiscitis, psoas abscess, and PJI after total hip arthroplasty and TKA in elderly or immunocompromised patients [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. These previous studies have demonstrated devastating sequelae due to atypical presentations often found in anaerobe-related infection. Unlike previously reported cases, however, we present a unique case of an early diagnosis of isolated P. micra PJI after TKA in a healthy patient with stiffness as the sole presenting symptom.

Case history

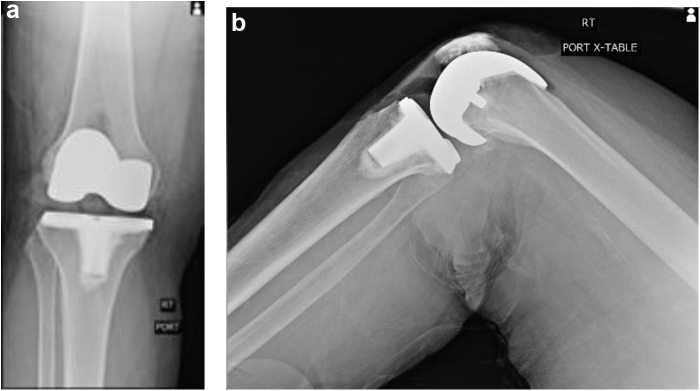

A 67-year-old female with a 2-year history of gingivitis was considered for right TKA for debilitating osteoarthritis. She had appointments with her dentist every 3 months, including deep dental cleaning just before the surgery. She had been taking prophylactic antibiotics for several days every 3 months for her gingivitis. She underwent uneventful TKA, using cemented Zimmer posterior-stabilized Persona (Warsaw, Indiana) implants. Following our standard protocol, she received 2 grams of IV cefazolin before the tourniquet and 1 gram of cefalexin orally on the evening after surgery and again the morning after surgery. She had no complications and was discharged in stable condition on the same day. In her first postoperative visit in week 4, she was noted to have a well-healing incision and a good range of motion (ROM). As seen in Figure 1, femoral and tibial components were maintained in good alignment. Shortly thereafter, however, she began to develop progressive stiffness. There was no apparent sign of infection such as fever, chills, erythema, effusion, or wound drainage. At 8 weeks postoperatively, she was noted to regress from 0-125 degrees of ROM in her first postoperative visit to 5-95 degrees in her second postoperative visit. Her incision was well-healed without any erythema, and the joint was not irritable to passive or active motion. She denied pain and was taking only acetaminophen and ibuprofen intermittently. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were ordered, and she was scheduled for manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) the next day. The ESR and CRP were 48 mm/hour and 37.9 mg/L. Owing to elevated inflammatory markers and noted clinical decline, the knee was aspirated, and MUA was performed.

Figure 1.

Portable views of patient’s right knee demonstrating recent postoperative changes of index TKA with posterior stabilized prosthesis. (a) (left), Anteroposterior view. (b) (right) Lateral view.

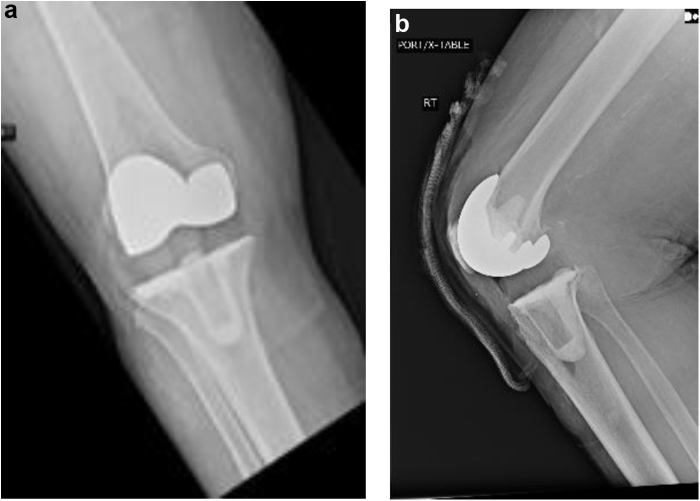

Synovial white blood cell count was 51,200 with neutrophilic predominance (91%), and the culture came back positive for P. micra 3 days after the sample collection. The knee was reaspirated because the microbiology report indicated that “this specimen could not be concentrated because [it] was grossly bloody… [and] culture results may be compromised.” After another 3 days of incubation, the culture was positive for the same pathogen. Sensitivities of this pathogen to antibiotics were not obtained as it is not our hospital’s protocol to routinely perform anaerobic susceptibilities unless specifically ordered. An infectious disease specialist was consulted and recommended ceftriaxone intravenous treatment without ordering sensitivities based on the pathogen’s generally established susceptibilities to beta-lactam antibiotics [12,13]. Resection arthroplasty with placement of an antibiotic-impregnated spacer was performed 3 months after the index surgery. Intraoperatively, she was noted to have cloudy synovial fluid with mildly inflamed synovium. Removal of the implants and thorough debridement were performed. A cement spacer containing 2 grams of vancomycin and 3.6 grams of tobramycin was placed as seen in Figure 2. Postoperative course with 6 weeks of ceftriaxone was unremarkable. She was allowed weightbearing as tolerated with a walker. Three weeks after the antibiotic was discontinued, the patient’s CRP was normalized to 8.9 mg/L with ESR of 9 mm/hour. Repeat aspiration resulted in synovial white blood cell count of 585.

Figure 2.

Portable views of patient’s right knee demonstrating interval removal of right TKA and placement of articulating antibiotic spacer. (a) (left) Anteroposterior view. (b) (right) Lateral view.

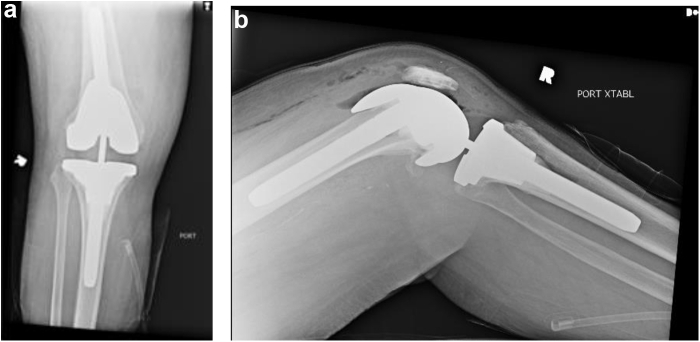

Six months after the index surgery and 3 months after the resection arthroplasty, the patient underwent the second stage of revision. After repeat debridement and explantation, she was noted to have a central cavitary defect in the proximal tibia. At the time of reimplantation, there was instability resulting from the 3 prior procedures and repeated soft-tissue releases. As a result, the surgeon opted to use a total stabilizer insert. Stryker Triathlon TS Revision (Kalamazoo, MI) implants with 100-mm stems and a conical sleeve were securely placed with antibiotic-impregnated cement, using 1 gram of vancomycin and 1.2 gram of tobramycin per pack (Fig. 3). Subsequent operative cultures were negative for any pathogens. The patient was maintained on prophylactic cefazolin and transitioned to twice daily oral cefadroxil 500 mg for 6 months after her discharge on postoperative day 1. The patient has continued to actively pursue treatment for her chronic gingivitis. Eight months after her last surgery, she is currently infection-free and walks independently without any pain and with knee ROM of 0 to 120 degrees. The patient provided the authors with informed consent to report this case in the literature.

Figure 3.

Portable views of patient’s right knee demonstrating recent postoperative changes of right revision TKA with total stabilizer insert. (a) (left) Anteroposterior view. (b) (right) Lateral view.

Discussion

Our case report demonstrates an atypical presentation of PJI after TKA due to a dental-related pathogen called P. micra. P. micra is a gram-positive coccus and obligate anaerobe that makes up the normal flora of the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract [14]. It is an opportunistic pathogen implicated in polymicrobial apical abscesses in immune-compromised patients [5] and, less commonly, in the brain, abdomen, and pelvis [15]. P. micra is also one of the most commonly isolated pathogens that remain in peripheral blood up to 30 minutes after scaling and root planning [16]. As such, there are case reports of this microbe causing spondylodiscitis, psoas abscess, and PJI after total hip arthroplasty [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. Despite this variability in presentation, P. micra is generally susceptible to most antimicrobial agents [14].

P. micra is an extremely rare pathogen in the setting of PJI, with a very limited number of reported cases (Table 1). To our knowledge, there are only 2 reported cases in the literature of TKA PJI secondary to P. micra [17,23]. Another 5 cases of P. micra causing a native joint infection have been reported [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. All the reported patients were either advanced in age or immunocompromised, and the majority of them had significant dental histories requiring aggressive treatment [[17], [18], [19],21,23]. Moreover, 4 reported cases of P. micra infection occurred in the setting of calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease [18,20,22,23]. Follow-up information regarding postoperative knee functionality was discussed in 4 patients, of which 2 regained complete ROM [17,22], one required a cane to ambulate [19], and one became wheelchair-bound [18].

Table 1.

Summary of 7 cases of P. micra infection in the knee.

| Study | Sex | Age | Native joint or TKA? | Onset of knee pain | Dental history | Associated CPPD | Antibiotic treatment | Invasive interventions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stoll, 1996 [17] | F | 68 | TKA | 4 y after TKA | Tooth abscess | No | 6 wk of IV clindamycin and IV rifampin | 12 d of daily needle aspiration and irrigation | Antibiotics continued for 2 mo after which dose reduced by 1/3 and continued for 2 y. No recurrence of infection and the patient regained full function of knee. |

| Riesbeck, 1999 [18] | M | 86 | Native | Sudden-onset | Bridges in upper and lower jaw but no periodontal disease | Since clinical relevance of the bacterial finding was considered vague, it was concluded that the diagnosis most likely was CPPD | IV cloxacillin | Arthroscopic irrigation | Found to have concurrent multiple myeloma without bony metastasis. Patient never fully regained function and became wheelchair bound. |

| Baghban, 2016 [19] | M | 65 | Native | Gradual onset for 3 wks | Dental work 2 mo before presentation; Periodontal disease without frank infection | No | 3 wk of IV clindamycin followed by 3 wk of IV ampicillin-sulbactam (switched due to allergic reaction to clindamycin) | Open irrigation and debridement | Normalization of ESR and CRP after 6 wk of antibiotic therapy. However, patient required a cane to ambulate. |

| Dietvorst, 2016 [20] | F | 68 | Native | Sudden-onset | None | Yes | 6 wk of po Clindamycin | Arthroscopic irrigation | Found to have concurrent CPPD disease. |

| Roy, 2017 [21] | M | 61 | Native | Sudden-onset after trauma | Dental cleaning 6 mo before presentation | No | IV ceftriaxone and metronidazole | TKA with debridement | Normalization of CRP after 10 wk of antibiotic therapy. |

| Sultan, 2018 [22] | M | 73 | Native | 2 d after local steroid injection | None | Yes | 6 wk of IV penicillin G | Arthroscopic irrigation | Patient regained full function of knee with some residual low-grade pain. |

| Bangert, 2019 [23] | F | 81 | TKA | 3 y after TKA | Periodontal disease without frank infection | Yes | IV moxifloxacin | TKA with debridement | Found to have concurrent CPPD Disease. Passed away from intraoperative cardiac arrest |

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; F, female; M, male; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; CPPD, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease.

Our case report is unique in that it demonstrates the onset of relatively rapid PJI, occurring only 1 month after TKA without concurrent calcium pyrophosphate deposition diseasein a healthy individual. The patient demonstrated a longstanding history of controlled gingivitis but exhibited no periodontal disease or active oral infection at the time of presentation. This patient’s clinical presentation is also atypical for PJI, as progressive stiffness was the sole presenting symptom. The patient did not present with fever, knee pain, localized erythema, effusion, or drainage, which are hallmarks for deep-knee infection [24]. In light of variable outcomes that other documented patients had from P. micra–related PJI, our patient was able to ambulate independently after the 2-stage revision TKA. This in part can be attributed to the relatively early detection of PJI that occurred as a result of the positive inflammatory markers, cell count, and cultures that were done at the time of the MUA. Early detection allowed for prompt surgical treatment and improved outcomes [25].

This case is also the only case in the current literature that involved the placement of an antibiotic-impregnated spacer in addition to 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotic therapy before revision TKA. Given the favorable outcomes of our patient, this report supports the use of antibiotic-impregnated spacers in the management of prosthetic joint infections secondary to P. micra. In addition, given that our patient did have recent deep dental cleaning before her index surgery and noting that 2 other reported cases of native joint infection have also been in patients who had dental work months before presentation, orthopedic surgeons should be cautious when operating on patients who report any history of recent dental manipulation [19,21].

We recommend that surgeons obtain a patient’s dental history before the operation. If there has been a recent dental procedure, surgeons should further investigate the extent of their dental history and if there is any lingering, persistent infection. All efforts should be made to postpone the surgery until the effects of the recent dental procedure are sufficiently resolved. Measures such as short-course oral antibiotics or use of antibiotic cement in patients with chronic gingivitis may be considered. One should note that the presence of mild periodontal disease in the absence of frank infection may still predispose healthy patients to developing this rare complication. Furthermore, any postoperative TKA patient that progressively loses motion in the setting of elevated inflammatory markers warrants infectious workup.

Summary

P. micra is a rare pathogen in the setting of PJI with a very limited number of reported cases. Previous reports demonstrate septic arthritis in native or prosthetic joints due to P. micra in elderly patients associated with tooth abscess and periodontal disease. Our case report uniquely describes PJI after TKA caused by isolated P. micra in a healthy individual with a sudden onset of stiffness as the sole symptom.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Kurtz S.M., Ong K.L., Lau E., Bozic K.J., Berry D., Parvizi J. Prosthetic joint infection risk after TKA in the Medicare population. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):52. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1013-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng J.E., Novikov D., Anoushiravani A.A., Schwarzkopf R. Total knee arthroplasty: improving outcomes with a multidisciplinary approach. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:63. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S140550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helwig P., Morlock J., Oberst M. Periprosthetic joint infection--effect on quality of life. Int Orthop. 2014;38(5):1077. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2265-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association AAoOSaAD . Evidence-Based Guideline and Evidence Report. 2012. Prevention of orthopaedic implant infection in patients undergoing dental procedures; p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siqueira J.F., Jr., Rocas I.N. The microbiota of acute apical abscesses. J Dent Res. 2009;88(1):61. doi: 10.1177/0022034508328124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoo L.J.H., Zulkifli M.D., O'Connor M., Waldron R. Parvimonas micra spondylodiscitis with psoas abscess. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(11):e232040. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-232040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Duijvenbode D.C., Kuiper J.W.P., Holewijn R.M., Stadhouder A. Parvimonas micra spondylodiscitis: a case report and systematic review of the literature. J Orthop Case Rep. 2018;8(5):67. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endo S., Nemoto T., Yano H. First confirmed case of spondylodiscitis with epidural abscess caused by Parvimonas micra. J Infect Chemother. 2015;21(11):828. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleaver L.M., Palanivel S., Mack D., Warren S. A case of polymicrobial anaerobic spondylodiscitis due to Parvimonas micra and Fusobacterium nucleatum. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4(4):e005092. doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.005092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrini B., Welin-Berger T., Nord C.E. Anaerobic bacteria in late infections following orthopedic surgery. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1979;167(3):155. doi: 10.1007/BF02121181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohra M., Cwian D., Peyton C. Delayed infection in a patient after total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(8):666. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchand-Austin A., Rawte P., Toye B., Jamieson F.B., Farrell D.J., Patel S.N. Antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical isolates of anaerobic bacteria in Ontario, 2010-2011. Anaerobe. 2014;28:120. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brazier J., Chmelar D., Dubreuil L. European surveillance study on antimicrobial susceptibility of Gram-positive anaerobic cocci. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(4):316. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy E.C., Frick I.M. Gram-positive anaerobic cocci–commensals and opportunistic pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37(4):520. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horiuchi A., Kokubu E., Warita T., Ishihara K. Synergistic biofilm formation by Parvimonas micra and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Anaerobe. 2020;62:102100. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.102100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lafaurie G.I., Mayorga-Fayad I., Torres M.F. Periodontopathic microorganisms in peripheric blood after scaling and root planing. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34(10):873. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoll T., Stucki G., Bruhlmann P., Vogt M., Gschwend N., Michel B.A. Infection of a total knee joint prosthesis by peptostreptococcus micros and propionibacterium acnes in an elderly RA patient: implant salvage with longterm antibiotics and needle aspiration/irrigation. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15(4):399. doi: 10.1007/BF02230366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riesbeck K., Sanzen L. Destructive knee joint infection caused by Peptostreptococcus micros: importance of early microbiological diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(8):2737. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2737-2739.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baghban A., Gupta S. Parvimonas micra: a rare cause of native joint septic arthritis. Anaerobe. 2016;39:26. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietvorst M., Roerdink R., Leenders A., Kiel M.A., Bom L.P.A. Acute Mono-arthritis of the knee: a case report of infection with Parvimonas micra and concomitant pseudogout. J Bone Jt Infect. 2016;1:65. doi: 10.7150/jbji.16124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy M., Roy A.K., Ahmad S. Septic arthritis of knee joint due to Parvimonas micra. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-221926. bcr2017221926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sultan A.A., Cantrell W.A., Khlopas A. Acute septic arthritis of the knee: a rare case report of infection with Parvimonas micra after an intra-articular corticosteroid injection for osteoarthritis. Anaerobe. 2018;51:17. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bangert E., Hofkirchner A., Towheed T.E. Concomitant Parvimonas micra septic arthritis and pseudogout after total knee arthroplasty. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25(4):47. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shohat N., Goswami K., Tan T.L. Fever and erythema are specific findings in detecting infection following total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Infect. 2019;4(2):92. doi: 10.7150/jbji.30088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abrman K., Musil D., Stehlik J. [Treatment of acute periprosthetic infections with DAIR (debridement, antibiotics and implant retention) - success rate and risk factors of failure] Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2019;86(3):181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.